In a previous post, I detailed some of the most interesting instances in which the LP version of a song by a major 1960s rock act differed from the one on the 45. Even without paying much attention to the ones where the single’s a few seconds longer, the LP has a different guitar part, the drums aren’t double-tracked, etc., there were a surprising number of these. So much so that I didn’t have room for all of the ones I could have written about. This post goes through some of the others, by acts who weren’t exactly minor, but weren’t as major as the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Beach Boys, Who, and others upon which I focused on my earlier post.

Phil Ochs, “I Ain’t Marching Anymore.” There are few instances in which the single is so different from the album version, and also in my view few instances in which one of the versions is so markedly superior. This anti-war protest anthem might be Ochs’s most famous song, with the possible exception of “Outside of a Small Circle of Friends.” It was the title track of his second LP, where it, like virtually everything Ochs did at Elektra Records in the mid-’60s, had an acoustic folk arrangement.

I say virtually everything because in February 1966, Ochs put out an electric version of the song on a UK-only single, with backing by the Blues Project. (It did come out in the US as a flexidisc with Sing Out magazine, although the flexidisc format was rarely employed in those days.) Although Ochs liked rock and was an early and vocal supporter of his rival Bob Dylan’s move from folk to rock, he didn’t seem to feel the need to make such a move himself, at least over the course of his first three albums, all of which were on Elektra Records. This electric version was simply far more musically dynamic and appealing than the plain folk one, with rollicking piano and what sound like bagpipes at the track’s beginning and end.

Why didn’t it get a general release in Ochs’s native US? “It was basically to test the waters,” Michael Ochs, Phil’s brother and (starting in 1967) manager, told me. “He wanted to expand his music, and so he thought, ‘Wouldn’t this be great, to do a rock version.’ I’m not sure that was his decision to be careful and only put it out in England. Phil was very tight with Murray the K, and Murray the K was on [New York’s] WOR-FM at that point, doing a very hip show. Every week he’d play like three new releases for major artists, and people would call in and pick their favorite. I know he played Phil’s electric ‘I Ain’t Marching Anymore’ against the latest Stones record and one other major one, and the calls that came in all said they loved Phil’s record the best.”

One shot-in-the-dark guess as to why it wasn’t released in the US is that Ochs wouldn’t be with Elektra Records that much longer. This single came out around the same time as his third and final (and best) Elektra LP, In Concert. If it was known at that time that Ochs was planning to leave for another label, Elektra might not have wanted to put too much into promoting a single that represented a departure from his folk sound, at a time when there was still some controversy about folkies going electric, though Dylan got the brunt of that flak. Ochs would indeed go into recordings with full backings by other musicians starting in 1967 with A&M Records, though these tended to be more eclectic, sometimes orchestral folk-with-pop-and-art song than straightahead rock.

One celebrity who did get to hear the UK single was not pleased. Asked for his reaction to the single in Melody Maker’s “Blind Date” column, Who singer Roger Daltrey snarled, “It sounds like a punished protest song. Turn it off, turn it off, turn it off! It’s not even good for my grandmother.”

For a record that was so hard to find in its initial incarnation, fortunately it hasn’t been hard to find on reissues. It’s been on the Rhino various-artists compilation Songs of Protest and the Phil Ochs box Farewells & Fantasies, and came out way back in 1976 on the double-LP Ochs anthology Chords of Fame.

Bob Seger, “2 + 2 = ?” There’s a bit of overlap between singles-only versions and some tracks I cited a few years ago in a post about prime ’60s rarities that have yet to be reissued. This is one of them, although it did get a low-profile reissue. To quote from the entry in that previous post:

“The original version of this oddly titled tune, as heard on a 1968 Capitol single, is not only Seger’s greatest recording, but also one of the rawest, most powerful anti-war rockers of all. But wasn’t that on his Ramblin’ Gamblin’ Man LP, you’re asking — an album that’s pretty easy to find used and cheap? Yes, but the seven-inch version simply destroys the tamer LP counterpart. And that’s not just collector talk that builds up cuts for their sheer rarity. The single has a searing intensity that couldn’t be matched, making the rationale behind a fairly limp album variation a mystery of its own.

Seger, as many of you likely know, seems to take an inordinate lack of pride in his earliest sides, though these are precisely the ones that will appeal most to garage rock enthusiasts. It was enough of a surprise that approval was finally granted for a CD compilation of his 1966-67 singles on ABKCO last year (the heartily recommended Heavy Music). What’s blocking the appearance of the original 45 take of “2+2=?” on CD is uncertain, not to mention unfathomable.

The Capitol 45 version was reissued as a vinyl seven-inch by Third Man Records. Backed by “Ivory,” it’s sold out. Yet it might not be the exact same version as you hear on the original single. As one reader wrote, “The 45cat.com site says this this Third Man reissue is in stereo and not the original mono 45 mix.”

The “2 + 2 = ?” single—the title, incidentally, is never vocalized in the song—was one of the relatively few rare records to gain a place in Dave Marsh’s book The Heart of Rock & Soul: The 1001 Greatest Singles Ever Made. Marsh called it “a thunderous crash of a record, with phased cymbals, pounding toms and snares, and a honking guitar. Seger’s finest achievement, though, was his lyric, which spelled out the inequity of what was going on in terms stark and terrorized first describing his own hatred of war and the men who might make him fight it, then telling about a high school friend, ‘just an average friendly guy’ who is sent to fight and winds up ‘bured in the mud of a foreign jungle land.’ And then he turns on the full fury of his Wilson Pickett voice and his overamped band.”

Judy Collins, “Who Knows Where the Time Goes.” Collins was a pretty big star, and “Who Knows Where the Time Goes” was the title track of one of her most popular albums, a 1968 LP that made the Top Thirty and eventually was awarded gold status. To this day, it’s the most widely heard composition by Sandy Denny, who was virtually unknown in the US when Collins covered this song. But it’s not well known that the LP version wasn’t the only version.

On the album, there was a full-band production and a key change. A far sparser, drumless arrangement sans dramatic upward key change was only on the B-side of “Both Sides Now” and the film soundtrack of The Subject Was Roses,though it later showed up on the greatest hits collection Colors of the Day. That anthology is pretty easy to pick up cheap used, and I don’t know whether the B-side version was ever issued on CD.

Judy Collins, “Chelsea Morning.” It’s also not so well known that Collins put a cover of Joni Mitchell’s “Chelsea Morning” on a 1969 single, two years before a different version was on her 1971 LP Living. The 45 version has a far more ornate, orchestral-informed arrangement; the LP is dominated by piano. The LP version is also a live recording, not a studio one, to judge from the bits of applause heard near the beginning and end of the track. The 45 track seems to be the one on the CD The Very Best of Judy Collins, though I don’t have the physical disc to check. Unlike her cover of another Joni Mitchell composition, “Both Sides Now,” Collins’s rendition of “Chelsea Morning” wasn’t a big hit, only reaching #78.

Tom Rush, “Urge for Going.” Also in the Elektra catalog, Tom Rush issued a cover of Joni Mitchell’s “Urge for Going” as a single in 1966, well before Mitchell issued her debut album in 1968. The 45 version of “Urge for Going” got airplay on Boston’s influential station WBZ, but didn’t catch on nationally. It’s more than two minutes shorter than the LP version, on the 1968 album The Circle Game. It’s also distinguished from its counterpart by a higher key, though it’s not enormously different in approach, other than the longer version allowing for some added ghostly keyboards (at least I believe it’s an organ or keyboard) near the end. The 45 version, perhaps unknown even to the kind of people who care about this kind of thing, appeared as a bonus track on a 2008 CD reissue of The Circle Game.

The Leaves, “Too Many People.” The Leaves might only be remembered for their hit “Hey Joe,” in part because it was selected for the Nuggets compilation. But they were a decent folk-rock-oriented group, if one with a short life. Their first LP, though uneven, is far better than their second and final one, which is of virtually no interest. The first LP also included, oddly, a different version of their debut 45 “Too Many People.” It’s half a minute longer than the single, but it’s decisively less impressive, with a more even tempo that’s far less effective than the one on the 45, which followed the rhythm of the Rolling Stones’ “Empty Heart.” It also just seems less energetic overall than the single, as if they were reluctantly forcing themselves to go through a song they’d already played many times in the studio again.

It’s a little puzzling why this bluesy, vaguely folk-rockish protest number was redone. The original single had reached #11 on the charts—I assume a local radio chart—in their native Los Angeles. It was also on the same small label, Mira, that issued the LP, titled Hey Joe. Maybe it was re-recorded because the Leaves’ lineup changed between the single and the LP, with guitarist Bill Rinehart getting replaced by Bobby Arlin. The original 45 version, fortunately, was a bonus track on the 2000 expanded CD reissue of Hey Joe, and even way before that, had been on the 1982 compilation The Leaves 1966, on the enigmatic Panda label.

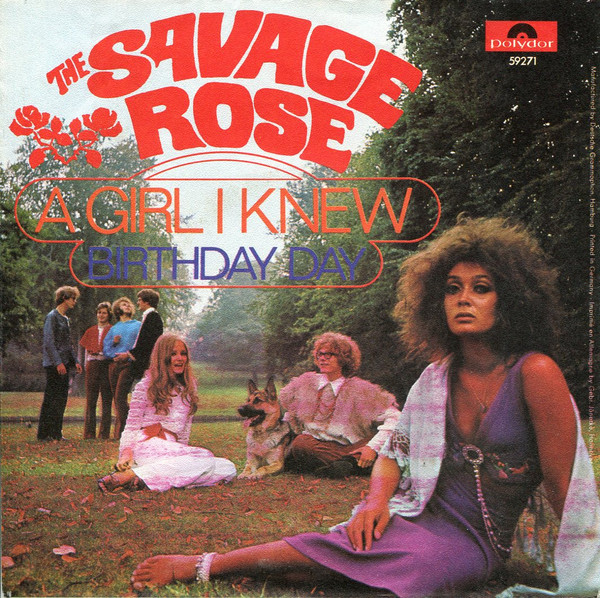

Savage Rose, “A Girl I Knew.” Savage Rose are not a big name in English-speaking countries, but they’re a big name in my house, as they were one of the best groups from a non-English speaking nation (Denmark) in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and I devoted a chapter to them in my book Unknown Legends of Rock’n’Roll. They were a big name in their native Denmark, where they at some points sold a lot of records, and made some impressions, if more on an underground/cult level, in some other European countries. Even in the US, they got some LPs released, did some shows (including the 1969 Newport Jazz Festival), and got complimentary reviews in Rolling Stone. They put out a lot of records, so this non-LP version of one of their best album tracks might have been overlooked even by dedicated collectors.

“A Girl I Knew” was a highlight of their 1968 self-titled debut LP, with a light yet slightly ominous psychedelic feel, interesting piano-organ interplay, and Annisette’s distinctive throaty, pinched vocals. It’s a little mystifying as to why they’d bother cutting an inferior slower, heavier rock version on a single that, to my knowledge, is extremely difficult to find on CD. It did show up on a huge eleven-CD various-artists box set Dansk Rock Historie 1965-1978, and I’m not sure any copies of that made it overseas; I’ve certainly never seen one. Making matters more confusing, it seems like there are three volumes in a box set series titled Dansk Rock Historie 1965-1978, of which this is just one, each bearing that identical title, though at least they’re in different colors. The one with the 45 version of “The Only Girl I Knew” is green.

As to why there was a remake for the 45 market, that might have had to do with a famed producer with whom they briefly worked. Polydor Records, perhaps sensing it could break the group into the international market, arranged some sessions in London with manager/producer Giorgio Gomelsky, a British impresario who’d worked with the Yardbirds, Soft Machine, Julie Driscoll & Brian Auger & the Trinity, and numerous other innovative UK artists. “He was a pretty wild guy,” Savage Rose guitaris Nils Tuxen told me. “It was known that he consumed a bottle of whisky every day, which is not a little.”

Obviously some effort went into this enterprise, as Gomelsky came over to Denmark beforehand to see the band play at Tivoli, Copenhagen’s famous amusement park. And going to Britain to record was not something a Danish band could do with casual ease in the late 1960s. “It was an interesting situation, because at that point, you were not allowed to go into England and record,” noted Tuxen. “It was strictly prohibited. The Musicians Union would not [allow] such a thing. So what the record company did…we went there and didn’t carry any instruments at all with us. They hired instruments for us. They even hired a session bass player who sat around for the entire time, just in order that our bass player could use his bass. Can you imagine that?”

But the collaboration was not a success, resulting only in an obscure single—the slower remake of “A Girl That I Knew” on one side, and the bluesy “Birthday Day” on the other. “In the studio, we just didn’t get to the place where our kind of creativity started,” Savage Rose keyboardist Thomas Koppel told me about the sessions. “We felt like the road was blocked somehow. It didn’t work out. In situations like that, we became anarchists.”

“That’s BS,” retorted Gomelsky when asked to give his side of the story. “The drummer [Alex Riel] was a professional musician, he knew a lot about music. You could talk to him. He saw very clearly what the ideas were. Annisette—great singer. We had no problems. With one of the [Koppel] brothers, I had terrible problems. One of them thought of himself as some kind of Viking god. Big-headed, big chip on his shoulder and knew zilch. It was very difficult to get anything out “of them and by consequence out of the session. He opposed everything, he stopped everything, he stopped work from flowing. We were getting nowhere.

“In London at the time, remember, we were flowing. We were in a groove. The engineers were hot, everybody was hot, we worked and went out and we celebrated. It was such an ‘up’ kind of situation. And there came this guy with this sort of negative kind of resistance. It just didn’t make for any agreeable environment. So I said, ‘I can’t do anything.’ But on the way there, we had some really good ideas, because Alex Riel—a pleasure to work with—was open to anything that made sense to him. Annisette, she was waiting, ready to wail away at the least opportunity. One of the brothers was cool. But then there was the other one. So it was not a happy experience. Truth to be known, you can pinpoint why.”

Whatever the reasons for this impasse, the resulting single did not succeed at raising the group’s international commercial profile, if that was the intention. It wasn’t the last time they hooked up with a big-name producer—they recorded Refugee with Jimmy Miller, who was also handling the Rolling Stones at the time, in 1971. But as Thomas admitted, “We were never really the typical kind of artists that wanted a producer at all.”

The few English-speaking collectors who are interested in finding Savage Rose rarities might want to know that Dansk Rock Historie 1965-1978—the volume that features their 1972 album Dodens Triumf as disc one, if you’re determined to track it down–also includes this single’s B-side, “Birthday Day,” and another non-LP single from 1969, “The Schoolteacher Said So,” which like “Birthday Day” isn’t so memorable. It also has…

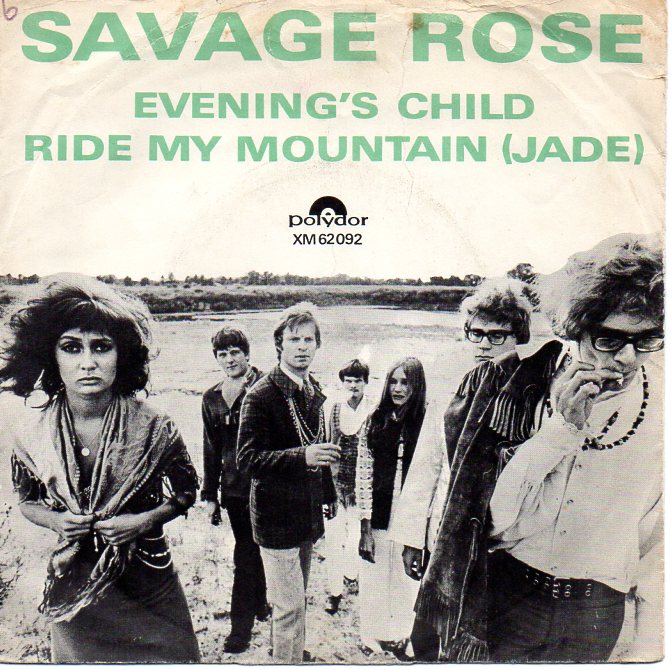

Savage Rose, “Ride My Mountain.” Used on the B-side of the Danish single “Evening’s Child,” the 45 version is about two minutes shorter than the one on their second album, 1968’s In the Plain. It’s faster and more intense, and though it’s not definitively superior to the LP counterpart, it’s worth hearing for Savage Rose completists. Although I’d guess fairly few of them will go to the effort of finding and buying the green-colored Dansk Rock Historie 1965-1978 box. It seems like it will cost at least $50 including shipping, going from the listings of copies for sale on discogs.com.

A smaller selection of post-1960s LP vs. single variations will be coming up in a future post.