I don’t hear as many rock reissues as I used to every year. So my best-of 2014 list is, no doubt, missing some titles that would have come in for strong consideration had I acquired them. I still heard enough, however, to build a Top Ten list of pretty strong releases, all of which have substantial merit.

As I explained in yesterday’s post about my favorite rock history books of 2014, a note about the parameter of the following list: You know those best-of 2014 lists you’ve seen this month? Well, in many instances, they’ve been compiled a few months before they appeared. That’s due to publication deadlines and, in my mind, a rather ridiculous belief that it’s more important to put best-ofs in an issue bearing a December or January date than to actually allow consideration of everything released in a calendar year.

All of the records below, however, bear a 2014 publication date. And this post wasn’t published until just a couple days before the end of the year. I suppose it’s possible something will arrive in the mail this week that I wish I could have included, but I considered everything I heard before the year came to an actual close. Indeed, I didn’t hear one of them for the first time until the day after Christmas.

Note that I’ve given several of these far lengthier reviews in issues #4, #5, and #6 of Flashback, the London-based ‘60s/’70s rock history magazine:

1. The Velvet Underground, The Velvet Underground: 45th Anniversary Super-Deluxe Edition (Universal). This six-CD box set is expensive and necessitates the purchase of much material many VU fans already have. But it’s a near-definitive document of their third album and their subsequent live and studio recordings (unreleased at the time) in 1969, with three different mixes of The Velvet Underground; all of the 1969 studio outtakes from VU and Another View; and two CDs of live recordings from late 1969, about two-thirds of which are previously unreleased. If, in an alternate universe, you’d never heard this music before, it would be a revelation. Most fans buying this have heard most of this before, so it’s not such a great value. As compensation, however, those eleven previously unreleased live ’69 tracks are really good, including some songs not presented in any form on 1969 Velvet Underground Live, like “I’m Set Free” and “There She Goes Again.” And some of the studio outtakes have notably different mixes, especially “Coney Island Steeplechase,” which gets rid of the annoying through-a-megaphone vocal effect and makes Lou Reed sound like a normal human being again. Read my full, lengthy review of this box for Record Collector News here.

2. The Bonniwell Music Machine, The Bonniwell Music Machine (Big Beat). I’ve said this before, but it’s worth saying again: too often dismissed as a one-shot group, the Music Machine had many excellent songs, and were one of the greatest garage rock outfits. Disc one is the definitive collection of the Music Machine’s later phase, including numerous underrated psychedelic/garage tracks that only found release on flop non-LP singles and an album (1968’s The Bonniwell Music Machine) that few people heard. Disc two, though less essential, is a historically invaluable assortment of demos and outtakes, many previously unreleased.

3. The Moody Blues, The Magnificent Moodies: 50th Anniversary Edition (Esoteric). Two-CD compilation of everything recorded by the original lineup of the band, when Denny Laine was their lead singer, including an entire disc of rare/previously unreleased demos/outtakes/BBC sessions. The Moody Blues, as most British Invasion fans know, were a much different group at their outset than they became by the time they moved into psychedelia and progressive rock. In the mid-‘60s phase this release documents, they specialized in haunting R&B/pop, with especially eerie vocal harmonies and a slight classical feel to the arrangements (particularly in Mike Pinder’s piano). Besides containing everything from their UK debut LP The Magnificent Moodies, this has a wealth of non-LP singles, some of them about as superb as their one big hit (“Go Now”), such as “From the Bottom of My Heart” and “Boulevard de la Madeleine.” Both of those songs were written by Laine and Pinder, responsible for all of the Moodies’ original material at this stage.

4. Bob Dylan, The Basement Tapes Complete: The Bootleg Series Vol. 11 (Legacy). While I don’t find this as godhead as many critics and Americana bands do, this six-CD box rounds up everything usable known to have survived from the quirky 1967 recordings Dylan made with the Band. This found the musicians working counter to most trends in rock music that year, mixing folk, country, blues, gospel, and rock’n’roll on idiosyncratic original Dylan material (sometimes written with help from Band members). They also ran through many covers, some quite obscure, though these have a rather loose, informal warm-up feel. So do some of the originals, many of which seem casual toss-offs or frustratingly incomplete. The most fully formed and celebrated songs – generally, the ones that also appeared on the 1975 Basement Tapes double LP – are available on a two-CD distilled version of this box, The Basement Tapes Raw.

5. Mike Bloomfield, From His Head to His Heart to His Hands (Legacy). Erratic three-CD box nonetheless has much fine music he recorded with Paul Butterfield, Electric Flag, Bob Dylan, and on his own, including some rare and previously unreleased stuff. Curated by his friend and frequent collaborator Al Kooper, it must be said that the first disc is by far the best, focusing on the mid-‘60s and including some previously unreleased tracks from a 1964 Columbia audition, as well as an alternate take of Dylan’s “Tombstone Blues” and an instrumental backing track to “Like a Rolling Stone.” Disc two is dominated by jams of varying quality, and disc three has a playing-out-the-string feel, but these still have their inspired passages. The box also contains an hour-long DVD documentary, Sweet Blues, that’s disappointingly short on archive footage, but has some informative, moving interviews with family, musical peers, and Bloomfield himself. My full-page review of this box appears in the March 2014 issue of Mojo magazine, though there’s no online link to it.

6. Various Artists, Halloween Nuggets: Monster Sixties A Go-Go (RockBeat). Three-CD set of all manner of ghoulish rockin’ oddities, highlights including Ervinna & the Stylers skin-crawling version of “The Witch Queen of New Orleans” and Kenny & the Fiends’ garage rocker “The Raven.” The absence of annotation besides original labels/years of release (which are noted on the covers of each disc) is disappointing, but the breadth is certainly impressive, jamming nearly 100 tracks onto the three discs.

7. Various Artists, Troubadours: Folk and the Roots of American Music Vol. 1-4 (Bear Family). Extensive, and generally well done, compilation of North American folk (and a bit of folk-rock) from the 1920s to the 1970s, heaviest on the 1950s and 1960s. Some of the entries are questionable and some big names are missing, but there are some rare off-the-beaten-track gems as compensation. Examples include Mike Settle’s gutsy “Hallelujah”; Earl Robinson’s “Joe Hill,” exhumed by Joan Baez at Woodstock; Terry Gilkyson’s “The Cry of the Wild Goose,” an unlikely #1 for crooner Frankie Laine a year later in 1950; and Paul Clayton’s “Who’s Gonna Buy Your Ribbons When I’m Gone” (from 1961), which was the obvious model for Bob Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright.” Notable absentees, however, include Peter, Paul & Mary, Simon & Garfunkel, and Leonard Cohen.

8. George Harrison, The Apple Years (Universal). All six of the albums Harrison issued on Apple, garnished with a few outtakes/rarities and an infomercial-ish DVD. Rewarding for its exhilarating peaks (All Things Must Pass and, to a more limited extent, the Wonderwall soundtrack); frustrating for the relatively few rarities and the dismal quality of his final records for the label. Had Harrison continued to explore the wildly diverse avenues of his first three releases (which also included the avant-garde synthesizer exploration Electronic Sound) under his name throughout his solo career, his catalog would be more nerve-wrackingly eclectic than Neil Young’s. Alas, he did not continue on the road less traveled, and the last half of the box is disappointingly ordinary, even mundane, in comparison. Beatles completists note: it does include a previously unreleased outtake, an alternate (though not very different) take of “The Inner Light”’s backing track.

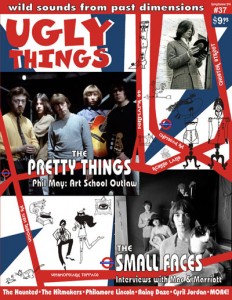

9. The Small Faces, There Are But Four Small Faces (Charly). Reissue of their US-only 1968 LP is stretched to fill out two CDs with a few alternate takes/mixes and the mono promotional DJ version of the album. But the packaging and notes are excellent, and it remains a fun listen even with all the padding. Also, though this was largely based on the 1967 UK Immediate LP Small Faces, it’s actually superior, adding three 1967 singles—“Itchycoo Park,” “Here Come the Nice,” and “Tin Soldier”—that simply improve the record a lot, much as the inclusion of Jimi Hendrix’s “Hey Joe,” “Purple Haze,” and “The Wind Cries Mary” made the US Are You Experienced a better listen than the UK version. Another good addition (or substitution, depending on your view) is the B-side “I Feel Much Better,” which almost could have been a hit in its own right.

10. Phil Ochs, A Hero of the Game (All Access). Technically speaking, this isn’t a reissue, but a previously unreleased live concert. It was a close call between this and another Ochs live performance (see review below). But I gave the nod to this previously unissued tape of a December 15, 1965 radio broadcast on WBAI in New York. True, the fidelity isn’t sparkling, though it’s okay. But the performances (particularly Phil’s underrated singing) are fine, including some songs that are not exactly common fare even on archival Ochs releases, like “Song of My Returning,” “Morning,” “City Boy,” and “White Boots Marching in a Yellow Land.” Some of his most famous tunes (“Crucifixion,” “Changes,” “Power and the Glory”) are represented as well. From a historical standpoint, this is interesting as just one of the songs (“Power and the Glory”) had been released at the time of this broadcast, indicating that his expansion into non-topical material — like “Morning,” “Song of My Returning,” and “City Boy” — was underway well before it became fully evident almost two full years later on his late-1967 album Pleasures of the Harbor. If you want more rare live Ochs, also check out the honorable mention below, Live Again!, which has a May 1973 show:

10a. Live Again! (RockBeat). Like A Hero of the Game, technically speaking, this is not a reissue, but a first-time issue of a May 26, 1973 concert. Not his best live recording, but an interesting addition to the many items in his discography that supplement his standard albums. There are solo acoustic versions of songs spanning his career, some of them relatively obscure, like “Boy in Ohio” and “Pretty Smart on My Part.” There’s little evidence of the depression/writer’s block that afflicted Ochs in his later years, though unfortunately it would be just three years before Phil committed suicide.

Honorable mention:

The Artwoods, Steady Gettin’ It: The Complete Recordings 1964-1967 (RPM). If the Artwoods are known at all by non-British Invasion fanatics, it might be for two things. Future Deep Purple keyboardist Jon Lord was in the group, and their lead singer, Art Wood, was Ronnie Wood’s considerably older brother. Make it three, maybe, for having Keef Hartley on drums, before he went on to a British blues career of modest success. The Artwoods put out a good number of singles and an LP, but never did have a hit even in their native UK, let alone the US. Musically their repertoire drew from much the same sources as other early British R&B bands like the Rolling Stones and Animals, and they have cult fans, though even on that level, they don’t have as many as some other British groups of the time who didn’t have a hit, such as the Action.

It’s amazing that such an obscure band has a three-CD set, but this is the era in which such dreams come true (and the Action, who never even had an LP, got a four-CD set four years later). This has all their seven of their singles, their LP, and their EP. Of most interest to hardcore collectors, it also has quite a bit of unreleased material in the form of BBC sessions, a pre-debut single acetate, and an entire CD of a live 1967 show, though the concert material has unfortunately rough fidelity. And the liner notes, in common with many RPM releases, are mini-book length, with eye-challenging miniature type as well.

Maximum praise for packaging, then. But the truth is, while I enjoy the Artwoods’ R&B/blues/soul/rock as I love that early British Invasion style, they were nowhere near as good as the Rolling Stones or Animals, to cite just a couple top-rank bands. They didn’t have much, or much really strong, original material, and Art Wood wasn’t that great a singer. More keyboard-based than many of their competitors, they did manage a pretty good gritty R&B/rock sound, Jon Lord distinguishing himself as their strongest contributor. The haunting yet swinging “Oh My Love,” written by a couple guys in a yet less celebrated British R&B band (Cops ‘n Robbers), is a little known near-classic. But really nothing else is on that level, or so good that you wonder why it wasn’t a hit. This will satisfy intense British Invasion lovers, of which I’m one. But less rabid ones should be content with a single-disc best-of, if they’re at all interested in second-to-third-tier British Invasion sounds.

Also in 2014: I published updated/revised/expanded ebook versions of some of my print books, with plenty of new material. All of these titles are available on Amazon, iBooks/iTunes, and other outlets:

Combines my two-volume history of 1960s folk-rock, Turn! Turn! Turn! and Eight Miles High, into one volume with updated material, including bonus 75,000-word mini-book detailing nearly 200 tracks. Click here or on the cover image above to order through Amazon.

Critical description of all known unreleased Beatles recordings, their most crucial unissued film footage, and more. Updated with 30,000 more words to reflect newly circulating material and additional information that’s come to light since the original edition. Click here or on the cover image above to order through Amazon.

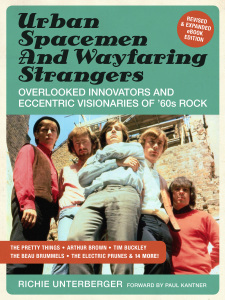

Documents twenty cult rockers from the 1960s. The book features extremely detailed investigation of the careers of greats like the Pretty Things, Arthur Brown, Richard & Mimi Farina, and Tim Buckley. The extensive chapters all include first-hand interview material with the artists themselves and/or their close associates. The ebook version is significantly expanded, revised, and updated from the print version, adding 20,000 words of new material. Click here or on the cover image above to order through Amazon.