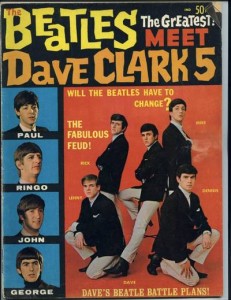

Dave Clark documentaries are not the usual things that PBS runs. But hey, better that than a broadcast featuring Pink Floyd tribute band Brit Floyd, right? (Which PBS has run recently — no joke.) Much better, in fact. But after it ran last week, the feeling almost people I got reactions from — and there were many, my Facebook post generating nearly 80 comments — was that it was rather unsatisfying, even flawed. The Dave Clark Five aren’t the usual subjects of analytical blog posts, but someone has to do it, and I thought I’d give it a shot.

It’s curious that a Dave Clark doc got on PBS in the first place. There’s speculation — much about Dave Clark is speculation, as there’s still some mystery about some aspects of his career — that perhaps he used his economic muscle to open doors that worthy British Invasion bands like the Zombies, say, could not. The Beatles’ Anthology documentary ran nearly ten hours in its home video version; The Dave Clark Five and Beyond, lasting just under two hours, nonetheless felt considerably padded to even reach that length. It had its pluses, but even those need to be offered with qualifications:

There was plenty of interview material with Dave Clark. Some of this, however, does not exactly look recent, or even that well-shot. Often his voice was heard as off-camera narration. I don’t know why exactly he’d be reluctant to be on camera, but it seemed curious.

There was also some interview material with DC5 singer Mike Smith, credited as (with Clark) co-songwriter of many of the band’s biggest hits. Presumably this was shot some years ago, as he died in 2008. There wasn’t enough of Smith’s observations, however, and it was curious that his songwriting contributions to the DC5 were not discussed. Or maybe not so curious — more on that later.

There were plenty of archive clips, even if these tended to be snippets that didn’t even last through the bulk of a song, let alone entire numbers. Even as the owner of three unofficial DVRs of vintage DC5 footage, some of this was new to me, and perhaps new to everyone, since some home movies were unearthed. I don’t remember seeing the blurry bit of the group being interviewed on an early US visit, for instance. But barely any of this showed the band actually playing live — more on this, too, in a bit. And this didn’t, as far as I could tell, have excerpts from a mid-‘60s short (also covering the Supremes) in which Clark was interviewed – which, unbelievably, I saw when it was shown in my fifth-grade music class in the early 1970s, but haven’t been able to see since.

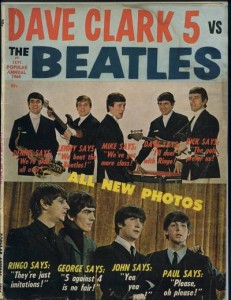

Believe it or not, for about six months or so in 1964, the Dave Clark Five were the most popular British Invasion band besides the Beatles.

Sentimental chap that I am, I found the memories of their war-deprived childhoods (which don’t, oddly, enter the picture until some way into the film) moving. Also it was moving to see DC5 bassist Rick Huxley tear up at their Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction. These honors do mean something to some musicians, especially ones whose names have been forgotten by most fans.

I liked some of the comments by other interviewees, though they often fell well short of substantial observations. Nice to see Stevie Wonder, for instance, acknowledge a Dave Clark influence, though he didn’t get specific as to what it was. Also nice to see Paul McCartney, who was as expected diplomatically kind without acknowledging any influence or interchange between the DC5 and the Beatles. It’s certainly a surprise to see Whoopi Goldberg in a documentary like this, but her affection for the band was sincere, and an illustration of how, for all British bands were accused of stealing the thunder of black Americans who influenced them, some black teenagers were fans of those same UK groups. I don’t like Gene Simmons or Kiss, but he actually came up with astute praise for the ascending melody of the Dave Clark Five smash “Because” — something I’ve pointed out in one of the rock history classes I’ve taught, albeit as an example of how the Beatles influenced their contemporaries.

So those are the pluses. Here are the minuses, some of which go hand-in-hand with the pluses:

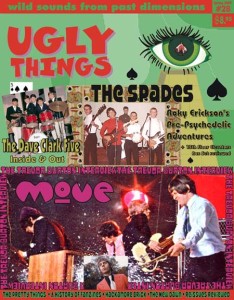

Not only were the interviews with Clark and Smith not all they could have been — no other DC5 members were interviewed. True, saxophonist Denis Payton died in 2006, but considering Huxley died just a year ago and there is late-life interview footage of Smith, presumably Huxley could have been fit in during production. Lead guitarist Len Davidson is not only still alive, but did at least one good interview about the group (in the spring 2009 issue of the top ’60s rock mag Ugly Things), and would no doubt have made an articulate participant. On top of all this, not only were there no interview clips with Adrian Kerridge — an engineer/producer who was a crucial architect of the DC5 sound (and the “Adrian” in the “Adrian Clark” credited as producer on their hits, “Clark” being Dave Clark) — he wasn’t even mentioned, once.

Almost none of the clips, and there were many, were performed live. Virtually all of them were lip-synced (including some from promo films, as well as their many TV appearances). Which leads to another “more about this later” item — was this a deliberate decision, perhaps because of their instrumental shortcomings, especially those of their leader…

There were way too many soundbites from celebrities with little or no direct connection to the DC5. What is Sharon Osbourne, husband of Ozzy, doing in a film like this? What’s Ozzy doing here, for that matter? Or Elton John, or Gene Simmons (praise of “Because” notwithstanding)? Their comments seem to amount to, yeah, we liked the band and were influenced by them, sentiments repeated and rephrased too often (perhaps to help flesh out that nearly two-hour running time) without much in the way of tangible examples. As balance, there are comments from ordinary Dave Clark fans who saw them back in the day – even if they don’t offer much in the way of revelation, though unsurprisingly they do offer much general praise.

Speaking of celebrities, the most obnoxious is Tom Hanks, whose histrionic R&R Hall of Fame induction speech is liberally excerpted. Yes, I know this wasn’t shot specifically for this documentary. But I like the Dave Clark Five. Honestly. I don’t need somebody yelling at me to convince me that they were good, or at least were good when they were at their best, which wasn’t always the case on their records. Whoopi Goldberg’s low-key humility was a welcome contrast, as was Clark’s own understated acceptance speech.

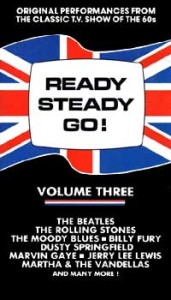

Also, a few minutes are devoted to Dave Clark’s acquisition of vintage Ready Steady Go episodes, which he did not obtain as an investment, of course, but for the love of it, and to preserve a vital piece of music history and popular culture. Great going, Dave. So why haven’t you made any of them available on DVD? And why haven’t you made the bulk of the DC5 catalog available on CD, while we’re at it? (Though it has recently gone up on iTunes, along with some actual previously unreleased DC5 tracks.)

Some of the Ready Steady Go episodes Dave Clark owns were issued on VHS, but none have been issued on DVD.

So there’s your mixed assessment. Now for some deeper delving into behind-the-scenes issues that some of the documentary’s flaws raise:

That absence of live clips, for instance. They’re not just absent from this documentary. There are virtually no non-mimed DC5 clips in circulation, even unofficially. That’s not just curious, that’s strange. Yes, every British Invasion band mimed a lot on TV, in movies, and in promo films. Yet there are also wholly live clips of virtually every British Invasion band of note. And not just by the obvious mega-icons like the Beatles, Stones, Who, Animals, Yardbirds, and Kinks. Even the much-derided Herman’s Hermits did a good number of live appearances for broadcast — and acquitted themselves quite respectably, I have to admit. Why so little DC5? What did they have to hide?

One clue might lie in a live clip from an early Ed Sullivan appearance (perhaps the first one) on which they bang out “Glad All Over.” Most of the band sound okay, though not great. The drummer, Dave Clark, sounds like he’s playing a trash can. Yes, the sound on TV in those days could be problematic. Did he get wind of how subpar they/he came off, however, and determine to only play to backing tracks from that point onward?

There’s been some speculation that Clark did not play on the DC5 records. In his interview in the spring 2009 Ugly Things, Adrian Kerridge says that top British session drummer Bobby Graham and Clark played on some sides to create an especially thick drum sound, though he doesn’t go as far as to intimate that Clark didn’t play, period. Here’s a telling remark from an interview with Mike Smith in the February 1991 issue of the UK monthly Record Collector:

Q: There was a story that a session drummer was used on the Five’s records.

Smith: I don’t wish to speak about that.

As to why their songwriting wasn’t discussed all that much, it’s also been speculated that Clark’s role in this was not as great as one might assume, given that his name’s on the credits of many DC5 hits. Another telling exchange from the February 1991 Record Collector:

Q: Dave Clark always got a credit on your songs. Would you like to elaborate?

Smith: I don’t wish to speak about that either.

More damningly, Ron Ryan — who was in several ’60s British groups who made records without landing hits, including the Riot Squad (with a pre-Jimi Hendrix Experience Mitch Mitchell on drums) and the Blue Aces — said in an interview in the winter 2009 Ugly Things that he wrote or co-wrote some DC5 songs without receiving credit, including the hits “Bits and Pieces,” “Because,” and “Any Way You Want It.” “When I sang a new song to Dave and Mike, Dave used to leave Mike and I to map out an arrangement and find a key suitable for Mike to sing in,” he told John Briggs. “Dave did not stay around as he was not musical, and he had no idea what Mike and I were talking about and found it all boring. However, to make it look as if the band were penning their own material (as with Lennon/McCartney), I agreed that Dave Clark would receive a songwriting credit. A deal was struck on a handshake between myself and Clark that, as soon as the money started rolling in, the songwriter would get a percentage of whatever his songs made. Soon after, the money was indeed rolling in for Dave Clark but I wasn’t seeing any of it.”

Explosive stuff, at least in the world of British Invasion fanatics. Ryan also says a solicitor even advised him to get an injunction to stop the release of “Any Way You Want It.” Ryan’s explanation of why he failed to do so is as odd as some other aspects of the DC5 story: “However, as I knew the boys in the band were on a weekly wage set by Clark, I felt that any bad publicity might hurt their weekly earnings, and so I waived my right to stop the record being released.”

Ryan does state in this article that “the issue of royalties was eventually settled out of court and some money did change hands, albeit far from the full sum I expected.” He thinks, however, that “Clark ripped me off for many hundreds of thousands.” This relatively little known controversy was not mentioned in the documentary.

Ron Ryan was singer in the Riot Squad, whose drummer was a young Mitch Mitchell (center); Ryan is on Mitchell’s left.

A somewhat more well known controversy unmentioned in the film is the failure of much of the DC5 catalog to get reissued on CD. Even the two major Dave Clark best-of compilations, the generally well done two-CD The History of the Dave Clark Five (1993, even if has some wrong dates in the track listings) and the inferior, less extensive The Hits (2008), are now out of print and expensive if you can even locate copies. Clark, as is well known, had the foresight to own the group’s masters, at a time when few artists did so. Why is he keeping such tight rein on their legacy?

There’s speculation, on Facebook if nowhere else, that he got this documentary out there in the first place to help get a better deal for DC5 reissues (and the Ready Steady Go episodes he owns). That’s impossible to say, but let’s be real about this, too. Having the DC5 catalog out of print is not nearly as grievous a tragedy as, say, much of the Kinks and Yardbirds ‘60s recordings being unavailable (as they were, believe it or not, when I started collecting their records as a teenager in the late 1970s). Their albums might not quite have been “uniformly bad,” as Lester Bangs proclaimed in The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll. But they weren’t very good, either, in part because they rushed out a dozen US LPs (not counting a couple greatest hits collections) between early 1964 and early 1968. There are some overlooked quality B-sides and LP-only tracks — see the section below for my favorites — but there were also a lot of generic stompers, some weak ballads, and even some easy listening instrumentals, along with songs that just weren’t too memorable or creative from any angle. And they didn’t grow musically, or with the times, nearly as much as the better British Invasion bands, let alone their one-time rivals the Beatles.

One Facebook poster said Clark’s writing an autobiography that, one would hope, might shed light on some of these murky areas. Given what little was divulged — controversial or otherwise — in the documentary, however, I wouldn’t count on that. The music does remain if you can find it (and as noted it’s on iTunes now if you must), and here’s a guide to 20 or so of the more obscure cuts you might have missed.

Chaquita (released April 1963): Even if it’s in the main a ripoff of the Champs’ huge late-‘50s instrumental smash “Tequila,” this is a ferocious wordless (save for menacing interjections of “Chaquita!”) rocker with spy-movie snaky sax and a jungle/exotica flavor. Issued as a UK B-side in April 1963, it’s most familiar in the US as the B-side of “Do You Love Me,” as well as a track on their maiden American LP, Glad All Over. Beware of the earlier, far inferior version they issued on their debut single in August 1962, which crops up on some compilations to this day, as Clark doesn’t own the right to those masters.

I Know You (released December 1963): Not much subtlety behind this grinder, just an out-and-out infectious rocker that, like many early British Invasion tunes from the Beatles on down, has a joyous abandon totally at odds with the downcast rejection lamented in the lyrics. Most known as the B-side to “Glad All Over,” it’s also heard on the soundtrack of the Pathe newsreel short done on the group (the same company did similar newsreels on the Beatles in late 1963, and the Rolling Stones in late 1964).

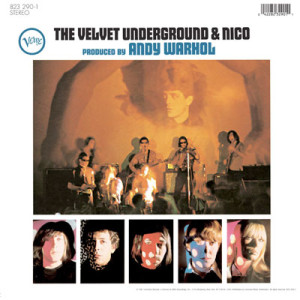

“I Know You” was the B-side of “Glad All Over,” the Dave Clark Five’s first and still most famous US hit.

Any Time You Want Love (released July 1964): One of the DC5 songs that switches adeptly between catchy near-ballad love song and more forceful midtempo rocker. Almost good enough to be a single, but not quite, ending up on their American Tour LP.

Whenever You’re Around (released July 1964): A harmony ballad with shimmering organ somewhat in the mold of “Because,” but slower and more wistful. Also from the American Tour LP.

Crying Over You (released October 1964): A nice Beatlesque ballad with close harmonies, heard on the B-side of “Any Way You Want It.” It’s not as good as the Beatles’ early ballads, mind you. But that doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy it. For what ballads are as good as the early ones by the Beatles?

When (released December 1964): A dramatic, haunting ballad with classical piano flourishes and more of their underrated close harmonies. The song was heard several times in their movie Catch Us If You Can (aka Having a Wild Weekend), suiting the film’s unexpectedly downbeat tone. It had already appeared on their Coast to Coast album, however, by the time the movie came out.

Don’t You Know (released December 1964): Also from Coast to Coast, this bash-it-out, get-it-over-with (one minute, 36 seconds) rocker has a little of a DC5-by-numbers feel. But as such filler on Dave Clark Five LPs goes, it’s one of the very best in that style, done with as much shake-it-on-out energy as if they’re doing one of their big hits, especially when the harmonies leap an octave at the very end.

Mighty Good Loving (released March 1965): Another tune that shifts from languid, moody verses to emphatic choruses, making good use of their underrated facility for minor-keyed melodies. From their Weekend in London album, not to be confused with their next LP just a few months down the line, Having a Wild Weekend.

‘Til The Right One Comes Along (released, March 1965): Also from Weekend in London, a real departure for the DC5, as it’s a folky ballad, acoustic guitar supplying the only accompaniment, save for a spot of piano at the end. The DC5 unplugged, perhaps. It sounds a bit like a demo that somehow didn’t progress into a full rock arrangement, which it could have easily been given, but it doesn’t suffer for that.

I’ll Never Know (released March 1965): An uncommonly moody, jagged rocker by the DC5’s upbeat standards, with some equally unusual double-tracked harmonica, from their Weekend in London album.

Remember It’s Me (released March 1965): A final highlight from their Weekend in London album has weird, even spookily echoing piano; another fetching minor-keyed melody, this time perhaps the DC5’s gloomiest; and more of their underrated back-and-forth tempo shifts. It’s their most haunting track, and had they come up with more creative items like “I’ll Never Know,” “Remember It’s Me,” “Don’t Be Taken In,” and “When” on their albums that departed from the usual formula they used on their singles, the DC5 would undoubtedly have more critical respect today.

Hurting Inside (released June 1965): The DC5 had more Beatlesque light rockers than many people remember, other than the oft-cited example of the one big hit they had in that vein, “Because.” Here’s one from the B-side of “I Like It Like That,” featuring a rare (for the DC5) extended guitar solo.

Don’t Be Taken In (released June 1965): Of all the Five’s Beatlesque songs, this is the one that would have come closest to sneaking on an actual Beatles album without raising too many suspicions. The piano-oriented arrangement slightly recalls the approach used on lower-key Beatles for Sale-era tracks like “No Reply,” and the high “no no”s at the end carry a whiff of those heard at the end of “Not a Second Time.” From their Having a Wild Weekend LP.

No Stopping (released June 1965): Like “Chaquita,” another instrumental with a devious surf-cum-spy guitar lick, this one filling out the Having a Wild Weekend LP. It’s not as good as “Chaquita,” but still has some good atmospheric sax bleating and frantic organ.

On the Move (released June 1965): Some of the Dave Clark Five’s instrumentals were throwaways of little value. This might be a throwaway too, but it’s much better than most of the band’s such efforts, sounding something like a collision between Link Wray, Johnny & the Hurricanes, and the surf instrumental hit “Pipeline.” Heard on the B-side of “Catch Us If You Can.”

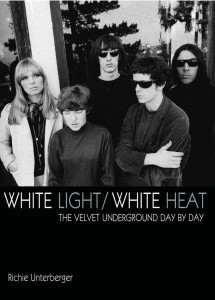

Also known as Catch Us If You Can, the 1965 film Having a Wild Weekend was no A Hard Day’s Night, although it had its good points.

I’ll Be Yours My Love (B-side of “Over and Over,” October 1965): A piano-based ballad with a rolling beat that would verge on the dainty if not for Mike Smith’s customary throaty, earthy vocals, nicely counterpointed by soft backup vocals.

I Need Love (released November 1965): A storming, almost garage-ish workout with one of Smith’s most leather-lunged vocals, ebullient shouts, and a dense blend of keyboards, bass, and Denis Payton’s trademark honking sax. From their I Like It Like That album.

I’m On My Own (released November 1965): The DC5’s periodic ventures into country were about as successful as their other outings into styles other than the straightforward rock they knew best — which is to say, not very. Here’s an exception, also from I Like It Like That, on this nice ballad with some twangy guitar and a brief, more British Invasion-friendly bridge.

All Night Long (released March 1966): Buried on the B-side of the early ’66 hit “Try Too Hard,” as filler B-side instrumental jams go, this is one of the best, with a heavier blues/R&B feel than anything else they cut. This could almost pass as a track by a genuine London R&B-rock British Invasion band, though the DC5 were never considered part of that scene.

Plus honorable mentions for these two hits which, although they reached the Top 20, are seldom if ever heard on oldies radio these days:

Everybody Knows (I Still Love You) (released October 1964): A fine, rather complex midtempo harmony rocker veering between wistful verses and more hard-hitting choruses. Not to be confused with their dissimilar, but similarly titled, 1967 single “Everybody Knows,” a far less notable ballad.

Try Too Hard (released March 1966): One of the band’s hardest rockers, with a curling guitar riff, pounding piano, and an insistent chorus. As a footnote, one of the first records I remember hearing, as my oldest brother was a DC5 fan.