I don’t just write books about rock music – I belong to a rock music book club that talks about them. Books about rock music in general, I mean, not my books specifically. I’m not that much of a glutton for Maoist self-criticism.

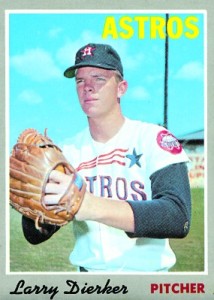

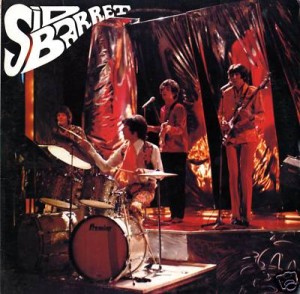

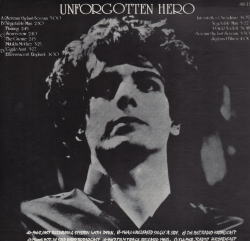

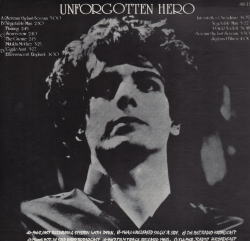

At our last meeting, we discussed Rob Chapman’s fine Syd Barrett bio A Very Irregular Head (Julian Palacios’s Dark Globe is also recommended). That prompted me to dig out, if only for decoration at the back room of a bar where we hold our meetings, this Syd bootleg I bought back in 1983. Note how it manages to misspell both his first and last names:

Credited to “Sid Barrett,” the Unforgotten Hero bootleg collected rare radio broadcasts and studio tracks from Syd Barrett’s time in Pink Floyd.

Great photo, though, of Pink Floyd in their pinkest psychedelic finery, probably just before Syd started his long downward spiral into true madness. And most of these BBC sessions, outtakes (including the legendary self-descriptive “Vegetable Man”), and rarities still haven’t come out as I type this more than 30 years later, though some have circulated in better sound quality on other bootlegs.

Looking at this album in turn got me thinking about the hole-in-the-wall specialist store where I bought the LP back in 1983, just after moving to San Francisco at the age of 21. I had no job, few prospects, and little in the way of disposable cash. Naturally much of it went to record-buying, especially as San Francisco stores had far greater goodies in the way of off-the-beaten-track imports, rarities, and illegalities than the city I’d moved from on the opposite coast.

Back then, you didn’t go on the Internet to find local record stores (let alone buy and listen to music on the computer). You, or at least I, went through the phone book. That’s where I found the listing for a tiny shop in the Outer Sunset district about a mile from the ocean, far afield from the neighborhoods that held virtually every other hip record store of note. The store was more or less as advertised, holding little except bootlegs, though of course that wasn’t the word used in the Yellow Pages.

Even by the standards of High Fidelity record emporiums, this was an eccentric outlet. Few were the occasions when anyone else was in the store save me and the owner, who never spoke to me save to mumble hello and goodbye. Never did he express the slightest interest in what I was buying or recommend anything that might interest me, though surely there couldn’t have been many other 21-year-olds making their way out to this mostly residential neighborhood in search of Beach Boys, Beatles, Stones, and Who outtakes. He obviously knew his stock, yet never played it in the shop; in fact, all he played was the radio, which was always tuned to either a football game or noxious adult contemporary station. It was almost as though he was purposely trying to drive his target audience out of the store with aural ambience that couldn’t have been more different than what he was actually selling in the racks.

Already so crowded with miscellaneous boxes and piles that surely would have had the space declared a fire hazard had the authorities bothered, each of my successive, sporadic visits saw the piles grow, seemingly unattended, like an updated version of Mrs. Havisham’s estate in Great Expectations. Eventually they all but obscured the window that let in what little sunlight the space admitted. I stopped going in the late 1980s, but it remained open, in theory at least, for years afterward, though no one (owner included) ever seemed to be there, and the pile of boxes grew so high that it eventually became impossible to even identify as a record store from the sidewalk.

But back in 1983-84, in its (relative) heyday, it was the best game in town for (relatively) affordable bootlegs of items that were positive manna from heaven for a ‘60s-starved fan like me. For $10 or $15, I was picking up listenable-to-hi-fi unreleased gems I hadn’t even suspected existed. Had my parents known I was spending my time and money like this when my bank account wasn’t even in the four digits, they no doubt would have flown across the country to stage an intervention or some such thing. But at the time, those records were more important than eating well – and they did, in time, prove invaluable acquisitions for my subsequent career as a rock music historian, more or less paying back the investment.

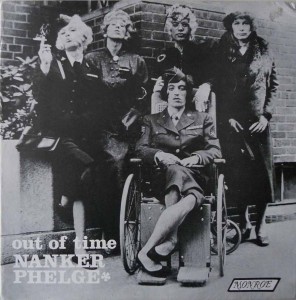

Anyway – what other goodies do I remember picking up at this rather unsavory establishment? Well, how could you not buy this LP of Rolling Stones rarities (still bearing its handwritten “$10—Excellent quality” label in my back room) after it leapt out at you from the bin without warning:

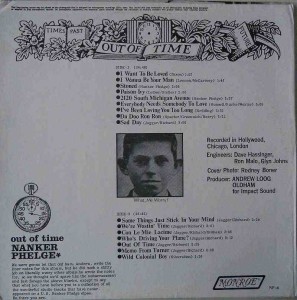

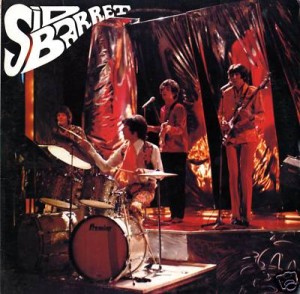

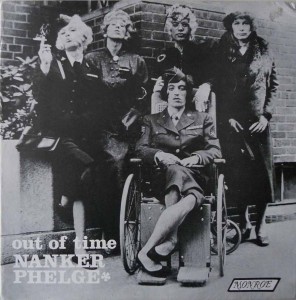

The Out of Time bootleg, credited to “Nanker Phelge.”

That’s the Stones, of course, from the legendary session where they dressed up as women—far more daring and controversial in 1966 than today—to promote the “Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow.” Note how the cover’s clever enough not to even identify it as a Rolling Stones product, trusting those hip enough to be lurking in stores like these can tell just from the photo, in-jokingly billing the band as “Nanker Phelge” (the pseudonym the Stones used for early collective compositions, as again anyone hip enough to finger this LP would already know). Note too how the “Monroe” record label apes the lettering used for “London” on the group’s US releases on the London label – repeated, for good measure, on the inner LP label of the actual disc.

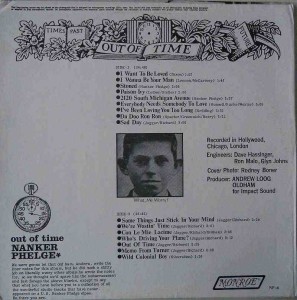

The actual contents were, as the liner notes stated in mock Andrew Oldham-ese, “a collection of all the wonderful studio tracks that have never appeared on a U.S. Nanker Phelge elpee. So there you are.” Yeah, okay, most of these are easily available on CD (or the computer, if you’re not willing to “pay” for it by standard means) nowadays, though they’ll cost you a lot more than $10 for each and every last track. Back then, though, you could not find most of this anywhere, or would have to pay a lot more than I could afford, even given my lax budgeting for necessities.

The back cover of the Out of TIme bootleg had Andrew Oldham-esque liner notes, as well as a picture of a very young Keith Richards.

Early B-sides “I Want to Be Loved” and “Stoned,” for instance? Second UK single “I Wanna Be Your Man,” even though it was a British hit? The long version of “2120 South Michigan Avenue,” only available on a German LP? All prime early Stones, and all only findable by haunting enough import bins and record conventions to jack the bill into the three figures (in 1983 money). A killer record, one that you’d play over and over again if you were a Stones fanatic, even digging the tracks that were lousy in most other contexts for their sheer oddity value, like the Italian version of “As Tears Go By” (“Con Le Mie Lacime”). Well, okay, it’s hard to enjoy “Wild Colonial Boy” (the folk song Mick Jagger sings in the dull 1970 movie Ned Kelly) under any circumstances, but at least they had the decency to make it the last (and hence easiest to skip) track.

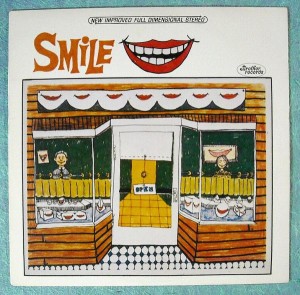

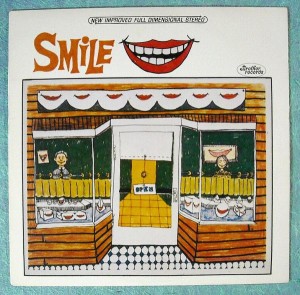

Another great find at the store-we-shall-not-name was the Beach Boys’ Smile, or at least an approximation of what the album might have sounded like. Keep in mind that this was when relatively little had been heard from those 1966-67 sessions for the most legendary unreleased LP of all time. Too, what had been written about it was fragmentary, contradictory, and itself rather hard to track down even if you were obsessive about it. We had no idea there’d be a Smile box set decades down the line, including most of the LP below and much more:

This 1983 edition of the Smile bootleg had liner notes attributed to James Watt, the infamous Secretary of the Interior who refused to allow the Beach Boys to play on the National Mall in Washington DC on July 4, 1983. The liner notes were dated on July 4, 1983, “to boot.”

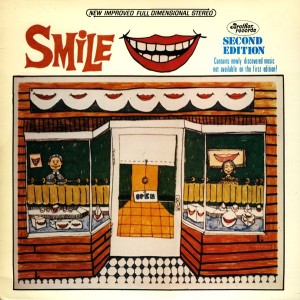

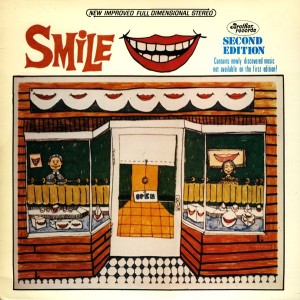

But back then—you know, back in the days when we waded through miles of chest-high snow drifts to reach our one-room schoolhouses—finding this album was like getting the key to a secret vault that few knew existed, let alone knew how to find. Even as the owner of the music from the Smile box today, I still find the official reconstruction of the record rather too slick and slightly ill-fitting, if only because I got so used to playing this bootleg over and over again as the best facsimile of the “real” version. Turns out they made some mistakes with that album, too, even including a Miles Davis track that the bootleggers thought had been recorded by the Beach Boys and/or Brian Wilson. At least they had the gumption to admit their mistake in the “new improved” (though actually quite similar) Smile bootleg that followed just a couple years or so later, with a frank, irreverent wit wholly missing from the liner notes to almost any official album you could name:

The “new improved” 1985 version of the Beach Boys’ Smile bootleg, with liner notes by “Nancy Reagan.”

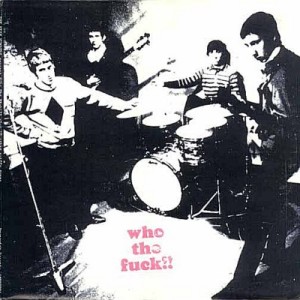

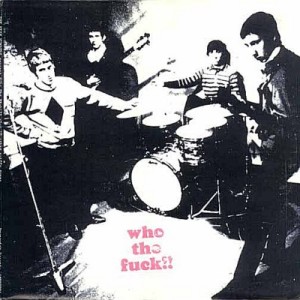

I got a couple great bootlegs of pre-Tommy Who boots at this pint-sized warehouse as well. Here’s another sleeve you’d never see on an official release back then. Come to think of it, you wouldn’t see it now, either:

A bootleg of Who rarities from the mid-to-late-1960s.

And again, a handwritten label stating simply, “$10—Excellent Quality.” The proprietor must have scrawled a lot of those.

But again, truth in advertising, including outtakes from their 1964 session for a single billed to the High Numbers, mid-‘60s BBC broadcasts, a Coke commercial, a Pete Townshend demo of “It’s Not True,” the weird lumbering instrumental version of “Hall of the Mountain King”…yeah, I guess most of this has come out on CD somewhere or other by now too, though probably in different, more sterile mixes. But I wasn’t especially inclined to wait a dozen or more years back in 1983. I wanted instant gratification, and this album, unmentionable by name in family circles, delivered the goods by the fistful.

What happened to that hole-in-the-wall, bootleg-mostly shop near the sea? I haven’t been out there to check in years. As previously noted, theoretically it was certainly still in operation in the 1990s and maybe beyond, though friends who used to live a few doors away could never recall seeing anyone actually enter the premises. Probably all of the music it sold is only a click away on your computer now, much of it having even gained official release.

At the time, however, that store was the best game in town if you wanted those goodies, even if it meant a long ride on the streetcar. And then a longer walk to the other side of Golden Gate Park to hit the vinyl stores in the Inner Richmond, back when saving 50-cent bus fares were as much a necessity as hearing that Smile bootleg. I don’t remember lugging those LPs on those hour-long trudges too fondly. But I remember that store kind of fondly now, even if those precious LPs it sold back in the day hold no collector value today except, maybe, for that odder-than-odd artwork. Which graced the back cover of that Pink Floyd boot as well:

Syd Barrett: Unforgotten Hero.