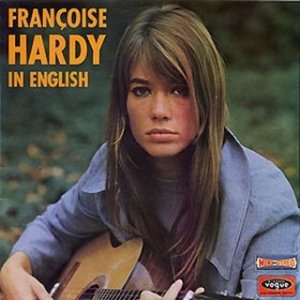

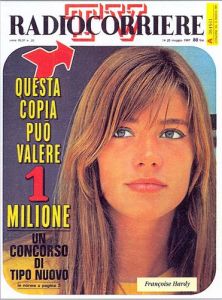

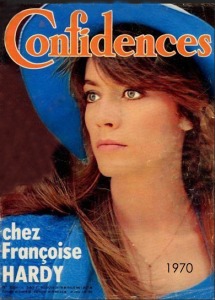

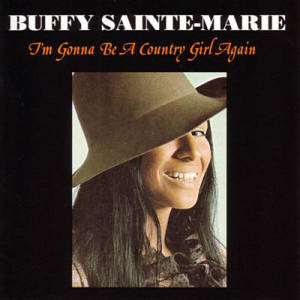

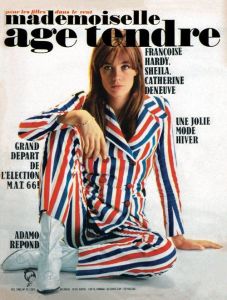

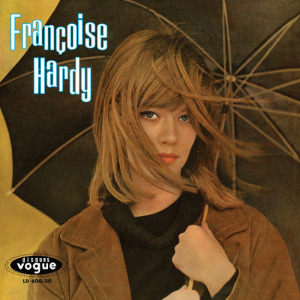

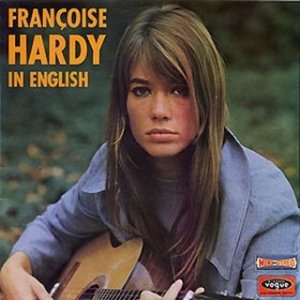

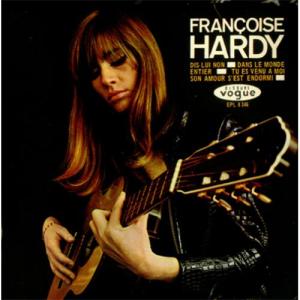

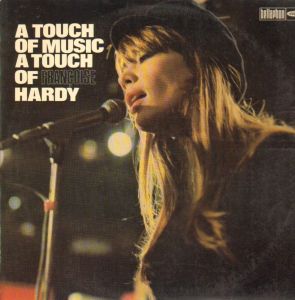

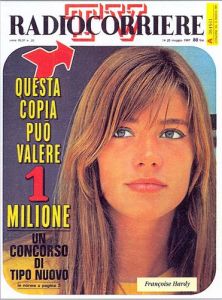

Recognition for the full scope of her achievements might have taken a few decades to take off outside of France, but Françoise Hardy to my mind is indisputably the finest pop-rock artist to emerge from that country in the 1960s. One of the things that set her off from the usual singers in the girl group-influenced yé-yé genre is that she wrote much of her own material. As good as her own songs were, she was often a superb interpreter of compositions by other writers as well.

Although I’ve been familiar with the bulk of her 1960s recordings for more than twenty years, the genius of much of her repertoire was reinforced by Light in the Attic’s CD reissues this fall of five of her 1962-66 French LPs. This marks the first time these have been widely available with comprehensive English-language liner notes, which note the oft-obscure sources for the songs she covered on these albums. I’d heard some of these original versions, but this made me more determined to hear the originals, and give more thought in general to this facet of her work.

While not all of her covers were great, Hardy’s overall record as an interpreter of songs previously released by others is flat-out impressive. That’s not simply because her versions were often markedly superior to the originals; nearly always at least as good; and seldom (except for a late-‘60s English-language LP where she tackled numerous well-known American songs) markedly inferior. It’s also because the songs she covered were extremely, almost absurdly diverse.

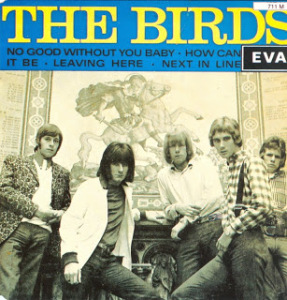

American girl groups, early rockabilly, pre-Beatles British rock’n’roll, country stars, pre-rock French chanson, Italian pop, Dusty Springfield, US and UK singer-songwriters, early-‘60s teen idols and instrumental rock, folk, folk-rock, even a bit of doo-wop and soul—all and some more were fair game for Françoise. There were unlikely connections to figures spanning Yardbirds singer Keith Relf to Ennio Morricone. Remarkably (again with the exception of that late-‘60s English-language album), very few of these were US or UK hits. A good number, indeed, were damned obscure, sometimes so much so that you wonder how she and/or her associates even became aware of them in the first place.

What follows is—for the first time in the English language, I would guess—a song-by-song comparison of the originals vs. her covers, with a couple caveats. I’ve lumped five songs from her 1968 En Anglais LP together, since as previously noted these are generally her least interesting covers, both in quality and choice of material. I’m also solely covering covers from her first and best decade or so of releases, spanning 1962 to 1972. Quite possibly I’ve missed a few songs she did that were previously released by other artists, especially among the handful of tracks she cut only in the German or Italian language. Any corrections or additions are gratefully received in the comments section.

We begin with a song from her very first release, which was one of the very first she recorded in a studio.

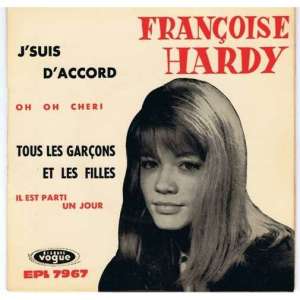

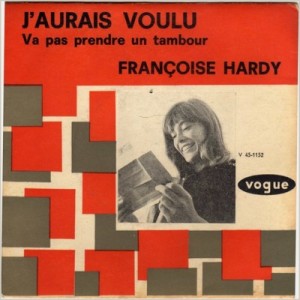

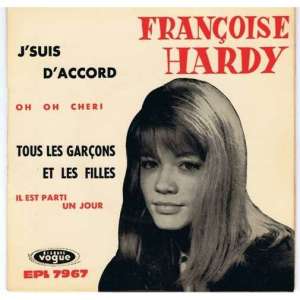

Oh Oh Cheri (French EP, Vogue, July 1962)

Original version: Bobby Lee Trammell (as “Uh Oh,”), 1958

Included on Hardy’s first EP, “Oh Oh Cheri” was a perky early-‘60s teen idol-type pop-rocker with a lickety-split beat. Enjoyable but a bit trivial when stacked against her greatest work, it turns out to have had a surprisingly large role in starting her career in the first place. It was this song that she was instructed to sing at her audition for Vogue Records in 1961. The audition was successful, and she recorded it on April 25, 1962 for her first EP. (The EP, rather than the two-song 45, was the dominant format for record releases in France at the time.)

In its original incarnation, “Oh Oh Cheri” was “Uh Oh,” a spry but mild 1958 US rockabilly single by one Bobby Lee Trammell, who didn’t make the charts with this record or any other. Trammell’s track, unlike Hardy’s, is burdened by whitebread doo-wop backing vocals, complete with goofy bass “bohm-bohm-bohm-bohm”s at the end of the choruses. Trammell also had a case of what we might call the “Holly hiccups,” with a vocal overtly influenced by Buddy Holly. Hardy’s version has the edge for its far greater, more relaxed playfulness, though there’s not so much you can do with a song so slight.

For all its slightness, it’s something Vogue apparently had high hopes for, adapting it into French with songwriters Jil and Jan, who’d also written for France’s top ‘60s male rock singer, Johnny Hallyday. The Hallyday connection didn’t end there—“Oh Oh Cheri” was designed as an “answer” song to Hallyday’s “Oh! Oh! Baby.” The Hallyday track, incidentally, is a rather dull, generic lovelorn early-‘60s rockaballad, and not enhanced by Johnny’s heavily accented English.

As for why Vogue artistic director Jacques Wolfsohn was so hot on “Uh Oh,” Hardy told Kieron Tyler (for the liner notes to the Light in the Attic reissue of her first LP), “He was also a publisher, and he got songs from the States. When he had heard my first audition on tape—he hadn’t seen me yet—he [told me] my voice was exactly right for ‘Oh Oh Cheri.’ That was one—not the only—reason he signed me.”

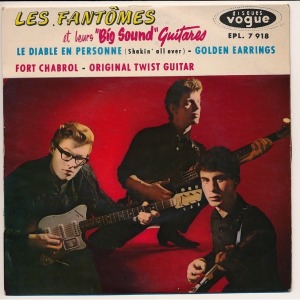

Le Temps de L’Amour (French EP, December 1962)

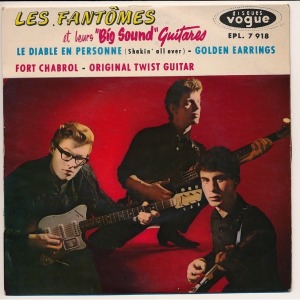

Original version: El Toro et Les Cyclones (as “Fort Chabrol”), circa early 1960s; possibly by Les Fantômes, January 1962

Hardy’s second cover, in contrast to her first, was one of her greatest and most famous recordings. Understandably, not many people even know it’s a cover, since “Le Temps de L’Amour”—boasting an almost James Bond noirish feel, with snaky spy movie guitar—was based on an instrumental with an entirely different title. Only after it was given lyrics did it become “Le Temps de L’Amour,” vaulting to worldwide fame of sorts about half a century later after being featured in the Wes Anderson film Moonrise Kingdom.

The melody of “Le Temps de L’Amour” was written by early French rock star (and later Hardy’s life partner) Jacques Dutronc, and used on a Shadows-styled instrumental titled “Fort Chabrol.” The liner notes to the CD reissue of Hardy’s self-titled debut LP say this had been recorded and released by Dutronc’s band El Toro & Les Cyclones. I can’t find a version by this group, but I did find one by Les Fantômes that I’m guessing is quite similar.

As played by Les Fantômes, “Fort Chabrol” is extremely similar to the early-‘60s work by the Shadows, the most popular rock instrumental group in Britain (and, with the exception of the US, around the world). Listeners all over the globe will instantly pick up its resemblance to vintage Shadows hits like “Apache.” Without the words that were later added, the melody of “Fort Chabrol” sounds a lot more like the Latin pop standard “Besame Mucho” as well.

“Fort Chabrol” is kind of cool, if extremely derivative of the Shadows. But “Le Temps de L’Amour” is much cooler, with the addition of lyrics and Hardy’s assured, seductive vocal—qualities she’d bring to so many of her records in the ensuing decade.

Je Pense à Lui (French EP, circa early 1963)

Original version: The Majors (as “A Wonderful Dream”), 1962

Until the late 1960s, “Je Pense à Lui” would have been one of the most familiar of the songs Hardy covered to American listeners, as it actually made #22 in the US in 1962 as “A Wonderful Dream.” The original version was cut by the Majors, a group (a la the Exciters, the Essex, the early Miracles, and the Platters) that was all-male save for one woman. In its initial guise, “A Wonderful Dream” was a very catchy uptempo late-period doo-wop tune. The Majors made the Top 100 just one more time before fading into obscurity.

Hardy’s cover is good-natured, but one of the few examples of an early-to-mid-‘60s recording of hers that doesn’t measure up to the original. Uptempo rock wasn’t among her strengths, and she doesn’t have the kind of ultra-high-pitched R&B voice that paced the Majors’ original. As was often the case with English-language hits translated into French, liberties were taken with the translation, “A Wonderful Dream” becoming “I Think of Him” (“Je Pense à Lui”).

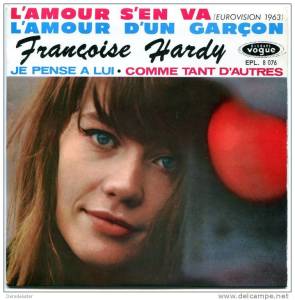

L’Amour d’un Garçon (French EP, circa early 1963)

Original version: Timi Yuro (as “The Love of a Boy”), 1962

Hardy’s first EP of 1963 also contained this cover of a Burt Bacharach-Hal David song, originally a small (#44) US hit for Timi Yuro. Françoise’s version of this decent but somewhat second-tier early Bacharach-David composition is more appealing. Yuro’s low voice sounds a little too earnest and forced; Hardy’s glides more naturally, and has a little more of a girl group feel. It’s infinitely more sensual, actually. Instrumentally it follows the original arrangement fairly closely, though it’s a bit faster, and the backing vocals have a more Continental feel. Incidentally, while Hardy herself gave the song new French lyrics, the title itself is an exact translation of “The Love of a Boy.”

Qui Aime-t-il Vraiment? (French EP, August 1963)

Original version: Johnny Crawford (as “Your Nose Is Gonna Grow”), 1962

Child TV star Crawford’s “Your Nose Is Gonna Grow” was quite a big hit in the US, rising to #14 in 1962. Crawford wasn’t quite a child anymore in 1962; in fact, he was 16. But you might not guess from his recording, in which his voice is so high-voiced that many might mistake it for a girl’s or woman’s.

Hardy is in general rather dismissive of many of her early-‘60s recordings, and one imagines that this is one of the tracks in which she takes least pride. But though the rather sub-teen-idol material isn’t the greatest, you wouldn’t know it so much from Hardy’s vocal, which is an archetypically measured, consistent, mature (though she was still in her teens) performance. The European orchestral pop production is nice too, though again one suspects not wholly to her liking. And Hardy’s French translation saves us from such awkward lyrics in Crawford’s original as “remember if you lie, the boogie man’ll get you, and your nose is gonna grow.”

On Dit De Lui (French EP, August 1963)

Original version: Connie Francis (as “It’s Gonna Take Me Some Time”), 1962

Connie Francis was still a huge star in 1962, “It’s Gonna Take Me Some Time” appearing on the B-side of her last Top Ten hit, “Vacation.” It might not be saying much, but “It’s Gonna Take Me Some Time” was one of the better, and more rock-oriented, sides from her vintage years, with a minor key and somewhat tougher cast than her usual tune.

That made it well-suited for an adaptation that could tap into Hardy’s knack for slightly noirish, devious rockers, a la “Le Temps de L’Amour.” In terms of its nervous tempo and Hardy’s coolly reserved vocal, as well as more spy-movie guitar, “On Dit De Lui” outdoes the original. It’s handicapped, however, by stiff-almost-to-the-point-of-histrionic doo-wopping backup vocals, presumably by French women with little or no experience singing or listening to rock music. It’s one of the relatively few occasions on which France-based production might have audibly hurt one of her tracks. There’d be less occasion for this to happen between mid-1964 and 1967, when she’d record in London instead.

Avant de T’En Aller (French EP, December 1963)

Original version: Paul Anka? (possibly as “Think About It”), 1963; possibly Sacha Distel’s “Ne Dis Rien,” 1965?

Of all the original versions discussed in this piece, this was the most vexing to research. This is referred to in the liner notes of the new CD reissue of her second album as a cover of a flop Paul Anka A-side from spring 1963, and as a cover of a ’63 Anka recording titled “Think About It” on the Françoise Hardy All Over the World website. But I couldn’t find a Paul Anka recording called “Think About It,” or an Anka single from 1963 that sounded like “Avant de T’En Aller.”

But Anka did record a song with the same melody, “Sunshine Baby,” which showed as a B-side of a 1964 German single. Weirdly, despite the title, it’s sung mostly in German. Even more weirdly, when the track appeared on one of Hardy’s 1963 French EPs, the title was given (in small type) in English as “Think About It” under the large-type title “Avant de T’en Aller” on the back cover. That back cover also gave “Anka-Hardy” as the songwriting credit. But this was the year before Anka’s “Sunshine Baby” was released.

According to a post on the website “Françoise Hardy – Mon amie la rose,” Anka did record the song in English as “Think About It,” but didn’t release it. Here’s an educated guess: Hardy, and/or her producer/record label, somehow got hold of the unreleased Anka recording of “Think About It,” or maybe even a demo of the song by Anka or someone else, or maybe even just the sheet music. Françoise then recorded a French version, writing her own French-language lyrics. Anka subsequently released a German-language version for the German market.

As additional confirmation that Anka wrote a song titled “Think About It,” it’s in the 1963 Catalog of Copyright Entries (crediting both Anka and Don Costa as composers). It’s also listed as a song he co-wrote with Don Costa (an A&R man at the ABC-Paramount label where Anka had his early hits) on Anka’s Songwriter’s Hall of Fame page.

However this all went down, Françoise’s version is easily superior to Anka’s more sentimental delivery, with understandably labored pronunciation given he’s singing in a language not his own. The arrangement’s pretty similar to Hardy’s, although it’s more heavily orchestrated, lacks Françoise’s nifty shifts into a quicker tempo on the bridge. But it’s not really that great a song to begin with, though it’s fairly typical of Anka’s early-’60s compositions.

There’s also a recording by male French singer Sacha Distel titled “Ne Dis Rien” which has the same melody as “Avant de T’en Aller” and “Sunshine Baby.” This track is referred to by some online sources (which are hardly flawless) as a version of a composition by Paul Anka and Don Costa called “Let’s Think About It.” That’s almost certainly the same song as “Think About It,” credited by (as noted above) other sources as an Anka-Costa work. Online sources (which, again, are not infallible) refer to this Distel track as a 1965 recording, however. (For what it’s worth, “Ne Dis Rien” translates to “Don’t Say Anything,” not “Let’s Think About It.”)

One thing we do know is that Anka was one of Hardy’s favorite singers as a teenager. And “Avant de T’En Aller,” wherever it came from, is one of Hardy’s most teen idol-type pop productions, from the sweeping (even lush) strings to the chirpy girl backup singers and pseudo-Latin beat. So it might not be to the taste of some rock-oriented listeners, but actually it’s quite enjoyable. And Françoise navigates the swoops into the lower register, as well as the transition to a jazzier bridge, with charming ease.

There might not be any relationship between “Avant de T’en Aller” and Distel’s “Ne Dis Rien” besides the melody. But check out Distel’s record anyway as an example of the rather rougher, more ostentatious way older male French singers of the time handled similar material—a manner that’s likely less to the liking of most twenty-first-century English-speaking listeners.

(Thanks to reader Christine for sending information about Anka’s “Sunshine Baby,” the credits on the back cover when “Avant de T’en Aller” appeared on Hardy’s 1963 EP, the post on the “Mon amie la rose” site, and the songwriting credits in the sources listed earlier in this paragraph. Her blog, Spiked Candy, is at spikedcandy.com.)

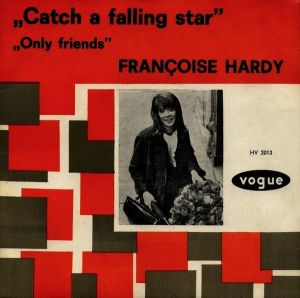

Catch a Falling Star (French En Anglais EP, Pye single UK, circa early 1964)

Original version: Perry Como, 1957

It was a testament to Hardy’s popularity that, within a couple of years of her first release, she was recording in English (and other languages besides French) as well as her native tongue. One of her first English-language recordings was “Catch a Falling Star,” a #1 hit in America for Perry Como in 1958. Even the liner notes of the new CD reissue of her third album call it “a weak version,” which isn’t nearly as harsh as Hardy’s own assessment in those same notes: “I hate ‘Catch a Falling Star.’ It’s stupid. It had nothing to do with me.”

So chalk this up as one of the few outright missteps in her early discography, perhaps in a misguided attempt to break her into the English-speaking market. It’s one of her least memorable early recordings, produced by Tony Hatch, most famous for his work with the Searchers and Petula Clark. That’s not so much due to Hardy’s vocal—which is, like virtually everything she did in the era, professional, if not as passionate as almost all her other tracks—as the ill-suited material, which is, as she herself says, “stupid,” and certainly unappetizingly middle-of-the-road.

C’est La Première Fois (French EP, early-to-mid-1964)

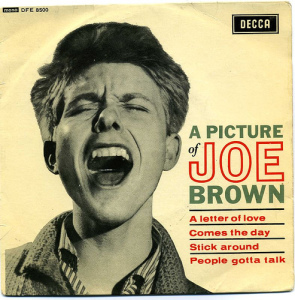

Original version: Joe Brown (as “Your Tender Look”), 1962

With their greater proximity to England, the French public and record industry would have been more likely than their American counterparts to be aware of pre-Beatles British rock stars. One of them was Joe Brown. With his sunny brand of slightly rockabilly-influenced, country-influenced pop-rock, he had three UK Top Ten hits in 1962-63, along with a half-dozen smaller hits in the early-‘60s. He never made the slightest impact in the US, where he might be best known—if he’s known at all—for doing the original version of “A Picture of You,” a 1962 #2 hit that was covered by the Beatles at their second BBC radio session in June of that year.

In common with most pre-Beatles British rock stars, Brown’s appeal is elusive to the great majority of American listeners. Judged on its own terms, and not against the early American rock stars (let alone the Beatles), some of his sides have a modest brisk country-pop charm. One such number was his wistful “Your Tender Look,” which was actually the follow-up to “A Picture of You,” though it didn’t do too well in his native UK, peaking at #31.

Hardy’s version isn’t radically different, also employing the kind of acoustic guitars and female backup vocals Brown used on his single. The Hardy recording is rather more forceful and energetic, however. And she’s a better and more interesting singer than Brown, which alone would make it more appealing to the average Françoise fan, though it’s not her most imaginative interpretation.

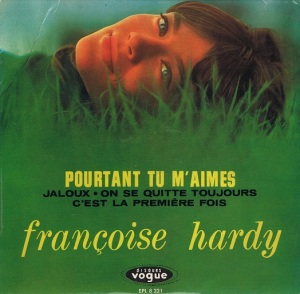

Pourtant Tu M’Aimes (French EP, early-to-mid-1964)

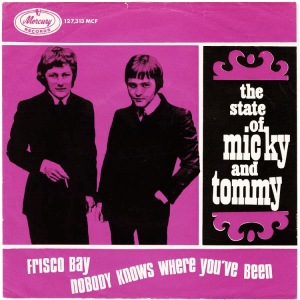

Original version: The Joys (as “I Still Love Him”), 1964

There were oodles—well, at least dozens—of blatantly Phil Spector-influenced productions in the early-to-mid-1960s, many of them featuring the same kind of girl groups that Spector recorded. One such obscurity was the Joys’ “I Still Love Him,” which failed to chart in the US. In France, it was somehow picked up by Hardy. It would be interesting to know if she found it herself, or if one of her associates—producer Mickey Baker (the same guy who was half of Mickey & Sylvia of “Love Is Strange” fame), say, or someone at her label or at a publisher—brought it to her attention. It couldn’t have been that easy to become aware of in France. It was hard enough to hear it in the land of its birth, the US.

Hardy and Baker did a credible job of recreating a Spectoresque sound with “Pourtant Tu M’Aimes,” with new lyrics by Françoise. The arrangement isn’t drastically different from the original, but the tempo is a little faster and the general feel brighter than the rather more somber treatment by the Joys. Hardy sounds like a genial observer or teller of the story; the Joys, in contrast, seem to be voicing a solemn lament. It’s a solid move to a fuller production sound that would become more pronounced when she used British producer Charles Blackwell on many of her mid-‘60s recordings.

C’est Le Passé (French EP, circa mid-1964)

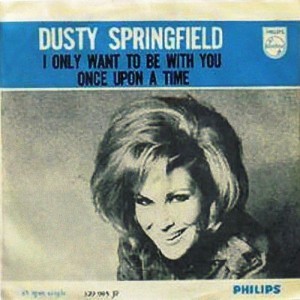

Original version: Dusty Springfield (as “Once Upon a Time”), 1963

Hardy did not often cover songs by well-known British or American stars before the late 1960s, and when she did, she sometimes opted for some of their most overlooked tracks. She’d done so in 1963 when she covered the Connie Francis B-side “It’s Gonna Take Me Some Time.” She did so again in 1964 on “C’est La Passé,” her French-language version of “Once Upon a Time,” which had been on the B-side of Dusty Springfield’s first solo single (and first international smash), “I Only Want to Be With You.” It was also one of the few songs Springfield herself wrote in her early career.

As noted earlier, Hardy usually matched or exceeded the originals she covered in quality. It’s tough, however, to take on Dusty Springfield and win; it’s not like taking on Joe Brown or the Joys. As a Springfield B-side, “Once Upon a Time” was a great daughter-of-Phil-Spector production, and indeed one of Dusty’s greatest overlooked tracks. Françoise’s version is okay, but it’s no match for Dusty’s from either a vocal or instrumental standpoint. And here’s one instance where Hardy’s suave approach was less suited toward the song than the more emotional, soulful one deployed by Dusty.

Pas Gentille (French EP, circa mid-to-late 1964)

Original version: Marty Wilde (as “Bad Boy”), 1959

Like Joe Brown, Marty Wilde was a pre-Beatles British rock star who’s barely known in the US. Most of his UK hits in the late 1950s and early 1960s were inferior covers of American smashes like “Teenager in Love” and “Donna.” He did, however, write the Top Ten hit “Bad Boy,” which like some of Joe Brown’s material had a country-cum-mild rockabilly feel. Alas, he didn’t sound so much like a “Bad Boy” as the boy next door.

Some lyrical tweaking was obviously necessary for Françoise’s cover, whose title “Pas Gentille” roughly translates to “That’s Not Nice.” While she doesn’t take many liberties with the gently ambling arrangement, she perhaps gives it a touch more country ambience. More importantly, the vocal is simply a lot more interesting, not to mention alluring.

Although as noted Wilde is all but unknown in the US, “Bad Boy” marked a rare instance of a pre-Beatles British rock single making a significant impact in the American charts. It rose to #45 in the Top Hundred in 1960, though I don’t remember it ever being played on oldies radio.

As an odd footnote, it seems like Hardy might have been mistakenly co-credited as a composer of “Bad Boy” when it appeared on discs released after her cover version first appeared. Complained Wilde in the July 2019 issue of Record Collector, “This annoys me, because Françoise bugged me off com;pletely. She had been claiming the song rights for ‘Bad Boy’ for many years; we have only just managed to stop it. All that happened was I wrote and recorded a song, ‘Bad Boy,’ then Françoise covered it and recorded it with French lyrics. But it’s still my song, not hers. But ever since it’s been listed as ‘Wilde-Hardy,’ like she wrote it, which is a joke.” Added Wilde unnecessarily, “I mean, Françoise might have written the French lyric but who bloody cares about France, anyway? Bloody French, they’re a pain in the arse!”

Je N’Attends Plus Personne (French EP, circa mid-to-late 1964)

Original version: Little Tony (as “Non Aspetto Nessuno”), 1964

Prior to this tour-de-force, Hardy had always stuck to American or British songs for cover choices. For “Je N’Attends Plus Personne,” however, she opted for a song first released in Italy as “Non Aspetto Nessuno” by Little Tony. I admit I don’t know how popular Tony was in Italy, but certainly he was unknown, then and now, to English-speaking audiences elsewhere.

Italian ‘60s pop generally does not make favorable impressions on English-speaking listeners, and I admit I’m one. The original starts off promisingly with growling guitar, but the production is overall thinner and more cornily dated than Françoise’s version, and Little Tony’s vocal a little hoarse and overwrought. In contrast, Hardy’s arrangement is tougher, with mean fuzz guitar (attributed to both Big Jim Sullivan and then-session man Jimmy Page), wailing female backup vocals, and a cool-as-a-cucumber vocal. It is one of her moodiest and even most menacing performances, without sacrificing her trademark soaring melodies.

This was one of the earlier of the numerous recordings Hardy made in the mid-‘60s with British arranger Charles Blackwell. And like some of the other Hardy-Blackwell collaborations, it was one of the best Phil Spector-like productions from Europe, adding some distinctive British and French sensibilities to the mix.

Je Veux Qu’Il Revienne (French EP, circa late 1964)

Original version: The Vernons Girls (as “Only You Can Do It”), 1964

Charles Blackwell was one of the few British arrangers who could fashion credible American girl group-styled records, and simulate the sound of Phil Spector’s productions. In fact, he may have been the only one. And he was certainly more adept at doing this than anyone in France. So he was a suitable collaborator for Hardy as she moved into more powerful, Spector-influenced sides in the mid-1960s.

Blackwell was also a songwriter, and it’s also no surprise that Hardy recorded—in both French and English—some songs he penned that had been cut by British artists with whom he worked. While some may sniff some unseemly self-cross-promotion involved in this, actually the Blackwell songs Hardy covered were good choices for her records, and not photocopies of the originals. Such was the case with “Only You Can Do It,” which had been a flop single for the Vernons [sic] Girls earlier in 1964.

The Vernons Girls had a handful of middling UK hits in 1962 and 1963, but didn’t have much longer to go after that, breaking up in spring 1965. “Only You Can Do It” is their best record, and one that could just about pass as an actual US girl group 45. Catchy and peppy (especially when it goes into double-time for the chorus), it’s nonetheless outdone—if not by much—by Hardy’s vivacious version. She recorded it in English under the original title of “Only You Can Do It” too.

If anyone outside of the UK is aware of the Vernons Girls, it’s likely because they were one of the several second-line (or more like third-line) British Invasion acts in the 1964 UK TV special Around the Beatles, in which the Beatles were naturally the headlining act. They also did one of the earlier Beatles novelty singles with “We Love the Beatles (Beatlemania)” in January 1964, but that couldn’t help them last past Beatlemania itself. The connection between the Vernons Girls and Hardy didn’t end with “Only You Can Do It,” however, as Françoise would cover a couple of the solo tracks issued by one of the Vernons Girls, Samantha Jones, in 1965.

Nous Étions Amies (French EP, circa late 1964)

Original version: Dino (as “Eravamo Amici”), 1964

One of Hardy’s most splendid and haunting mid-1960s ballads had its origins as a song, and with an artist, few people in the UK or North America would have known. “Nous Étions Amies” was first recorded by Italian singer Dino as “Eravamo Amici.” A melodramatic ballad (like so many Italian pop records of the time), it had its virtues, namely that haunting melody. The opening desolate, echoing percussion was nifty too. But the arrangement was overblown, especially in the farting horns, and Dino was far less nuanced a singer than Hardy.

In contrast, her interpretation is nimble and arresting, both vocally and instrumentally. The horns are eschewed for tasteful piano trills, staccato guitar notes, ghostly female vocals, and expertly flung flecks of reverberant chords. And the wordless scatting “oh oh” simply sounds far more affecting from a higher-voiced woman singer.

Dis-Lui Non (French EP, circa early 1965)

Original version: Bobby Skel (as “Say It Now”), 1965

Possibly the most obscure song Hardy covered—in the face of some pretty stiff competition—was “Say It Now,” translated into “Dis-Lui Non” (“Tell Him No,” in English). American blue-eyed soul singer Bobby Skel wrote this ballad (credited to his birth name Robert Skelton), and released this on the B-side of “Kiss and Run,” on the little-known Soft label. “Kiss and Run” didn’t make the national charts (and nor did any of Skel’s other records), but according to one youtube clip, it made #6 on the chart of Chicago radio station WLS in early 1965.

In its original version, “Say It Now” is a classy pop-soul ballad, opening with a stuttering piano figure much like the one kicking off the 1966 Rolling Stones UK B-side “Long Long While.” Skel was white, but many listeners then and now would mistake him for African-American, his singing backed by lilting soulful backup vocalists and a piano-dominated arrangement. The poppier “Kiss and Run” might have been the hit in Chicago, but “Say It Now” is the more memorable song by some distance.

Hardy’s version is quite different, putting more emphasis on the guitar (especially in some almost bluesy spiky lines near the end of some lines). Although it was a 1965 release, it was a bit of a throwback to the doo-wop/teen idol-influenced approach of her early, pre-London recordings. While Hardy’s covers were often more cool, calm, and collected than the originals, here’s an instance where Skel actually sounds a bit more reserved, and Françoise a little more emotive and yearning. And she’d record this song in English under its original title as well.

Son Amour S’Est Endormi (French EP, circa early 1965)

Original version: traditional German folk song “Alle Nächte”; possibly Tommy Kent, 1960

Unlike any of the songs discussed so far, this isn’t based on any specific previous record or version. “Son Amour S’Est Endormi” is Hardy’s adaptation of the traditional German folk song “Alle Nächte.” It can’t said for certain which version or record she might have learned this from, or if she even learned it from a performance or recording, traditional folk songs often passing on through other means. It does seem quite possible she based it at least on part on German pop-rock singer Tommy Kent’s 1960 version of “Alle Nächte,” whose arrangement is similar in some respects, especially in the backing vocals.

Though it’s more testimony to her versatility, it’s one of her weaker mid-‘60s recordings, particularly in the semi-stentorian backing choral vocals. It’s not one of her more typical ones either, combining country-ish piano, folky acoustic guitar, and a rather more liltingly frivolous vocal delivery than her usual wont, especially when she wordlessly scats.

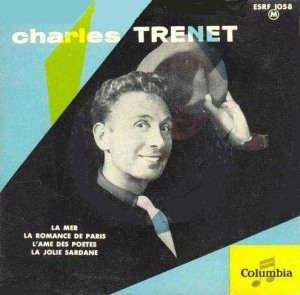

La Mer (German LP Portrait in Musik, 1965)

Original version: Charles Trenet, 1946

A track so obscure that I don’t remember seeing it on any CD reissue, “La Mer” was first released on the 1965 German LP Portrait in Musik, a mixture of German-language songs with French-language tunes such as this one (and one English-language track thrown in for good measure). Before 1965, all of the songs Françoise covered had been originally released in English or Italian. Here, after all this time, is her first cover of a French-language song (though she’d recorded numerous French-language songs by other composers that had not previously released by anyone else).

Dating from well before the rock era, “La Mer” was first issued back in 1946 by Charles Trenet, a quite popular French singer-songwriter who—certainly these days—is little known outside his native land. The song is certainly well known everywhere, though. In addition to being one of the most famous standards of any kind in France, in 1960 it became an American Top Ten hit for Bobby Darin, who sang it in English under the title “Beyond the Sea.”

Trenet’s original recording will bring to mind the kind of sentimental songs performed in vintage romantic movies of the 1940s, complete with operating singing, grand swelling orchestration, imposing backup choral vocals, and melodramatic piano trills. Hardy’s version, frankly, can’t compete with either Trenet’s or Darin’s. With one of her corniest arrangements, it sounds like a leftover from her earliest sessions, or perhaps something done as an afterthought for a foreign market, with musicians and arrangers with whom she usually didn’t collaborate. The movie-soundtrack strings and glee club backup vocals in particular are not characteristic of her ‘60s recordings, though her singing’s fine.

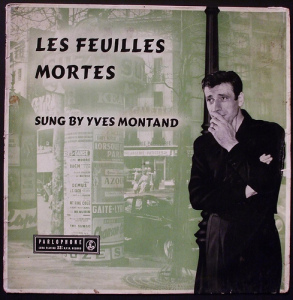

Les Feuilles Mortes (German LP Portrait in Musik, 1965)

Original version: Yves Montand, mid-1940s

In some ways, “Les Feuilles Mortes” occupies a similar place to “La Mer” in this overview. It’s one of Hardy’s most obscure 1960s recordings; it also found release on the German Portrait in Musik LP; it’s a French-language song; it was originally done by a singer immensely (and primarily) popular in France; and it’s familiar to English-speaking audiences through versions that use English lyrics.

“Les Feuilles Mortes” was first popularized by French singer Yves Montand (better known in North American and the UK as an actor, particularly for his role in the 1953 classic Wages of Fear) in the mid-1940s. His recording of the song from that time is stark. Rickety piano backs the sad, elegantly—and, typically for French pop, suavely melodramatic—sung melody. In those respects, it’s not too unlike many of Hardy’s own compositions, though she’d sing her haunting songs in a more straightforward fashion.

American and British listeners will recognize the melody, as with English lyrics by famed songwriter Johnny Mercer, it was changed into “Autumn Leaves.” Recorded by many singers, including Jo Stafford, Frank Sinatra, and Nat King Cole, it became a standard and, in an instrumental version by pianist Roger Williams, a #1 hit in 1955. Eric Clapton even did it on his 2010 album Clapton.

Here’s one respect in which “Les Feuilles Mortes” differs from “La Mer,” however—Hardy’s cover is better this time around. Backed primarily by acoustic guitar and piano, with a strange cha-cha beat, it avoids the orchestral excesses on her arrangement of “La Mer.” According to a youtube clip—not the most reliable of sources in all cases, it should be cautioned—“she reportedly hates this version.”

Hardy had another brush with Montand in the mid-1960s, incidentally, but outside the recording studio. She had a small role in the 1966 film Grand Prix, starring Montand as a champion race car driver.

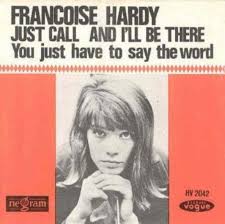

Le Temp des Souvenirs (French EP, circa mid-1965)

Original version: Samantha Jones (as “Just Call and I’ll Be There”), 1965; and/or P.J. Proby (as “Just Call and I’ll Be There”), 1965

When Samantha Jones left the Vernons Girls in mid-1964, she continued to work with Charles Blackwell, who’d produced and written their 1964 single “Only You Can Do It,” covered later that year by Hardy. He also wrote “Just Call and I’ll Be There,” the B-side of her second single, which was released in February 1965.

Perhaps too good to be wasted on a B-side, it was a nice, tuneful midtempo number graced by atmospheric female backup vocals, orchestral swells, and smidgens of what sounded like steel drums and flamenco guitar. It was a little reminiscent of the girl group-cum-British Invasion pop being generated by Dusty Springfield, Lulu, and Sandie Shaw at the time, though Jones would never have a UK or US hit. And, as with “Only You Can Do It,” it was just a hop, skip and a jump to reconfigure it for a Françoise Hardy record.

It must be said, however, that Hardy’s cover absolutely trounces Jones’s rendition. Indeed, it’s one of her most decisive victories in the covers vs. originals department. It’s one of her sexiest, strongest vocals, and even the sha-la-la-la’s of the female backup singers are quite intoxicating. Jones’s relatively faceless vocal is a telephone book reading in comparison. And while the arrangement isn’t that much different (no surprise as Blackwell oversaw both versions), Hardy’s track is considerably more powerful by that measure too, especially in the orchestral crescendos at the end of the choruses.

It’s possible the original version of “Just Call and I’ll Be There” was recorded and released by another UK-based artist, American expatriate P.J. Proby. The song appears on his debut LP, which charted in the UK in February 1965. A big star in the UK by that time, Proby never had comparable success in his home country, and while there will be those who vehemently disagree, I don’t think he deserved it. His version of “Just Call and I’ll Be There” is inferior even to Samantha Jones’s, with a pinched vocal style that brings to mind an anemic Gene Pitney, especially when he histrionically climbs the high notes of the chorus.

Hardy wasn’t done with the Blackwell-Jones connection after “Just Call and I’ll Be There” (which she recorded in English as well as a French translation). She’d cover the A-side of Jones’s second single, “Don’t Come Any Closer,” on her next French EP.

Non Ce N’est Pas Un Rêve (French EP, circa late 1965)

Original version: Samantha Jones (as “Don’t Come Any Closer”), 1965

Released in February 1965 as the A-side of Samantha Jones’s second single (the B-side was also covered by Hardy; see above entry), “Don’t Come Any Closer” was another track more impressive for the production and song than her vocal. A quality mixture of girl group, British pop, and a bit of soul, it had a dramatic soul-pop melody, booming (nearly bombastic) orchestral production, and wailing female backup vocals. Samantha’s singing, however—veering between a girlish whisper and more conventional belting—wasn’t in the league of Dusty Springfield’s, Lulu’s, or for that matter Françoise Hardy’s.

Hardy was really reaching an extraordinary peak on tracks like “Le Temps des Souvenirs” (her other Samantha Jones cover; see previous entry) and “Ce N’est Pas Un Rêve,” which were Righteous Brothers-strength in their grandiose production. Her vocal again makes this a decisive triumph—indeed rout—over the Jones original, especially in the beguiling husky low tones of the verses and the almost forlorn, wistful ones she breaks into after the orchestral crescendos. More great sassy female backup vocals on this track, too, which wisely begins with an arresting instrumental opening, rather than bursting right into the chorus as Jones does.

Quel Mal Y A-T-Il à Ça (French EP, circa late 1965)

Original version: Patsy Cline (as “When I Get Through With You”), 1962

We’re back to more familiar territory here: a cover of an American song that wasn’t a big hit. Patsy Cline was a big country star by the early 1960s, and some of her songs were also big pop hits. “When I Get Through With You,” however, wasn’t one of them. It peaked at #53, though it made it to #10 in the country listings. Although I have a half-dozen or so Patsy Cline compilations, it doesn’t appear on any of them, and I didn’t hear this original version until I prepared this article.

It wasn’t as much of a stretch for Hardy to cover Cline as you might think. In the early 1960s, several singers who straddled country and pop made some singles with a girl-group feel, sometimes with great success, as Skeeter Davis did with “I Can’t Stay Mad at You” (and Brenda Lee did on a few hits). “When I Get Through With You” seems to be an attempt by Cline to reach into this style, with a bouncy verse and catchy chorus, and not all that much country after the slow, nearly a cappella introduction.

Hardy had a greater affinity for girl group pop than Cline, and her version is better, though not as different from the original as you might guess. Her singing is more, well, girlish than Cline’s. The arrangement uses the same kind of backing vocals and dancing strings as the original, but with a little more verve.

La Maison Ou J’Ai Grandi (French EP, circa early 1966)

Original version: Adriano Celentano (as “Il Ragazzo Della Via Gluck”), 1966

Hardy turned her attention to covers of Italian songs in 1966, the first of those being Adriano Celentano’s “Il Ragazzo Della Via Gluck.” If you think French pop of the time was sentimental, it had nothing on its Italian cousin, though at least this acoustic ballad had a swinging rhythm. Acoustic guitars were joined by violins halfway through the song, backing Celentano’s rather operatic delivery—a trait shared by many male Italian singers of that time, and of other eras.

I have the feeling I’m in the minority on this, but Hardy’s adaptation—“La Maison Ou J’ai Grandi”—isn’t among my favorite mid-‘60s tracks of hers. I find it a bit meandering and, yes, sentimental. But if you’re not a fan of Italian ‘60s male-sung pop (I admit I’m not) and a fan of Françoise Hardy (as you likely are if you’re reading this), you’re certain to like her version better. There’s a more even, unexaggerated lilt to her vocals, and some bluesiness to the hastily picked opening acoustic guitar riff. The liner notes to Light in the Attic’s CD reissue of the first LP on which this appeared speculate that it’s the work of Jimmy Page.

American listeners are most likely to be familiar not with Hardy’s version (or certainly not with Celentano’s), but with yet another translation of the Italian original. As “Tar and Cement,” it became an unlikely Top 40 hit for Verdelle Smith in 1966, who gave it a treatment combining folk and orchestral pop.

Il Est Des Choses (French EP, circa early 1966)

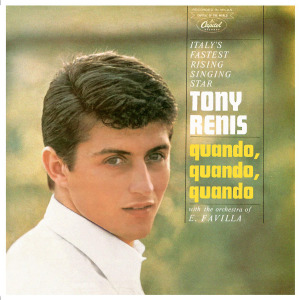

Original version: Tony Renis (as “Ci Sono Cose Piu Grandi”), 1966

Hardy was generally drifting away from rock, albeit of the poppiest orchestral-girl group sort, and into more sentimental pop in 1966. One of her targets was “Ci Sono Cose Piu Grandi,” by Italian singer Tony Renis. His version starts off with a rather eerie sequence of what sound like high organ notes, then easing into a fully arranged dramatic ballad. Not a minute’s over before the sweeping strings and crooning backup vocals enter; one of those singers goes into a ghostly soprano a few lines later. It might be a layered, mannered production, but as the cliché goes, for what it is, it’s pretty good. The tune’s appealingly melancholy, and Renis doesn’t overdo the opera as much as many of his peers, though there’s some of that in the orchestral climaxes.

Appearing on the same EP as “La Maison Ou J’Ai Grandi,” Hardy’s French version, “Il Est Des Choses,” has a significantly sparer arrangement emphasizing rolling piano. There’s some strings here, too, but they’re more subtle, and her singing is nicely nuanced, as if she’s just about keeping her emotions below a boil. There’s also a neat passage where it slows down dramatically for the finale without sounding contrived. It’s not as superior to the Tony Renis original as I might have predicted, but it’s another notch in her victory column.

Je Changerais d’Avis (French EP, circa mid-1966)

Original version: Mina (as “Se Telefonando”), 1966

Another Italian singer who’s likely unknown to record collectors from North America and the British Isles (even if they specialize in ‘60s pop), Mina had a hit in her homeland with “Se Telefonando.” Like Adriano Celentano’s “Il Ragazzo Della Via Gluck” (covered by Hardy earlier in 1966 as “La Maison Ou J’ai Grandi”), there was some folkiness to this sentimental pop. And like “Il Ragazzo Della Via Gluck,” albeit in a different fashion, it was a little unconventionally structured for a pop song, moving into a different melody and tempo for the chorus that could have almost been airlifted from another composition.

Hardy tones down the more overt mannerisms of Mina in her vocal—no surprise there—and gives it a far, frankly, breathier approach. She does march into a more determined mode for the chorus, without taking the pile-on climax into grandstanding territory. It’s a bit of a surprise, however, when she repeats the chorus instead of going back into the verse, which makes this one of her more aggressive (relatively speaking) mid-‘60s productions and performances. Like “Il Ragazzo Della Via Gluck,” it’s not one of my favorite Hardy tracks from the era, but I like it better than the original, as it’s almost like the more grating features have been sanded off into something more palatable.

This track marked a little-known connection between Hardy and another giant from the era, though from a much different field. “Se Telefonando” was co-written by Ennio Morricone, who even by 1966 was a top soundtrack composer, and might now be the most highly regarded soundtrack composer of all time.

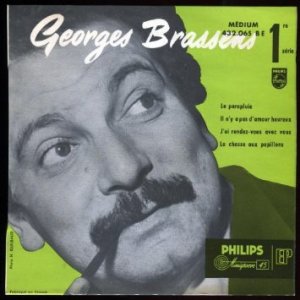

Il N’y a Pas d’Amour Heureux (French EP, circa late 1967)

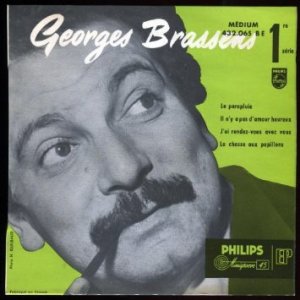

Original version: Georges Brassens, 1954

Another major figure in pre-rock French pop who will likely be unfamiliar to English-speaking readers, Georges Brassens set a poem by Louis Aragons to music for “Il N’y a Pas d’Amour Heureux” in the mid-1950s. More somber and yet more melancholy than many of Hardy’s own melancholy compositions, a strong sense of loss and lament comes through on the Brassens original even if you don’t understand any French. The sadly strummed acoustic guitar brings to mind a fisherman pouring out his sorrows by the dockside. If nothing else, tracking down the original versions of Françoise Hardy songs gives you a chance to sample strains of French pop you might be unfamiliar with, and I think this prototype of “Il N’y a Pas d’Amour Heureux” will be one of the most appealing to non-French audiences.

Hardy’s version emphasizes rolling, almost classical piano as the backing. Actually, there’s no backing but piano until some mournful strings join in the gloom at around the halfway mark, joined by some doleful choral backup vocals in the final section. It’s a little different hearing this sung by a young woman rather than a more experienced man (Brassens was in his early-to-mid-thirties when he recorded it), which puts an interesting different spin on the record.

Hardy’s interpretation, then, is quite different, and respectable. But, a little to my surprise, my overall preference is for the Brassens original. You can certainly have both, however.

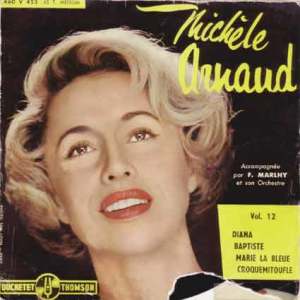

Ma Jeunesse Fout Le Camp (French EP, circa late 1967)

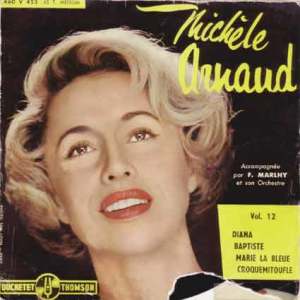

Original version: Michèle Arnaud, 1962

Much as 1966 had seen Hardy focus on Italian songs when she covered outside material (though it should be kept in mind that she was writing most of her own repertoire), 1967 saw her concentrate on French songs when she opted for cover tunes. Less well known than the likes of Yves Montand and Georges Brassens, Michèle Arnaud had nonetheless been active on the French recording scene for quite some time by the late 1960s. Not at all part of the yé-yé scene, she was already in her early forties by the time she recorded the original version of “Ma Jeunesse Fout L’Camp” in the early 1960s.

I’ve already described many songs in this post (whether by Hardy or others) as sad, wistful, and melancholy. That doesn’t mean this doesn’t fit in this category as well, declaimed by Arnaud almost as though it’s a poem—something this shares with Georges Brassens’s “Il N’y a Pas d’Amour Heureux.” Unlike some of the Italian and French male singers Hardy covered, Arnaud gives this original version a nicely controlled, subtle vocal that gets the serious emotions across without hammering you with them. The orchestral production is nicely understated, too, though it shows no influence from the rock music that was part of Françoise’s style from the start.

Although Hardy was only 23 in 1967, she seemed to be making a determined move toward a more mature, less rock-oriented style. Of course you could be mature and rock hard too, as the Beatles, Rolling Stones, and so many others were proving. But that wasn’t Hardy’s bag, at least at the moment, and perhaps plumbing for non-rock covers that had first been issued more than five years ago was part of that process.

Whatever the motivation, “Ma Jeunesse Fout L’Camp” was one of her less memorable tracks, though it was used as the title of her 1967 LP. Her interpretation is okay, but not too different or imaginative, and a bit formulaic if there was such a thing on Hardy’s ‘60s records, the expected violins and cloudy-day choral vocals entering after the acoustic guitar-dominated opening sections.

La Fin de L’Été (French LP Ma Jeunesse Fout L’Camp, 1967)

Original version: Gerard Bourgeois, 1963 and/or Brigitte Bardot 1964

The third and final of Françoise’s French covers to appear in 1967 was quite different from the previous pair. “La Fin de L’Été” (“The End of the Summer”) was, in contrast to much of her output, easygoing and upbeat. It might have been lushly produced—it’s a bit over-lush in comparison to her previous productions, actually—but the muted angst and overt melancholy characteristic of many of her slow and midtempo ballads is absent. It sounds a bit frivolous in the context of her overall work, in fact.

I haven’t, unfortunately, been able to track down the original 1963 version of “La Fin de L’Été,” issued in 1963 by its co-composer, Gerard Bourgeois. It seems possible, however, that she based her cover on Brigitte Bardot’s 1964 recording of the song, or at least was aware of Bardot’s version as well. Bardot’s arrangement, as you might guess, is a little more in the yé-yé vein, with a jazzier backing featuring acoustic guitar, piano, and Herb Alpert-like trumpet. Her vocal’s a hell of a lot more frivolous than Hardy’s, as you’d definitely expect.

Hardy is definitely a better singer and recording artist than Bardot, who really did records (and quite a few of them) as a kind of adjunct to her principal career as an actress, often with an irreverent playfulness suggesting she wasn’t taking her musical endeavors too seriously. Nonetheless, I have to admit I like Bardot’s version of “La Fin de L’Été” better. Not because she’s a better singer or more creative, but because the material suits her better, and she brings a more appropriate approach to this rather lightweight piece of froth.

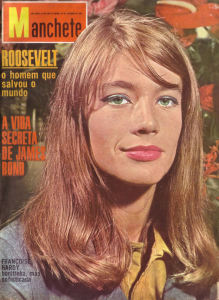

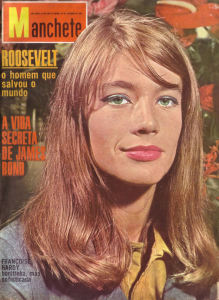

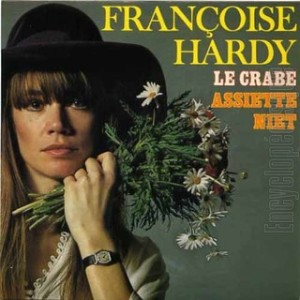

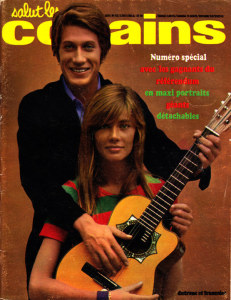

Brazilian magazine cover, September 1964

Il Est Trop Loin (French LP Ma Jeunesse Fout L’Camp, 1967)

Original version: Peter, Paul & Mary (as “Sorrow”), 1962; and/or traditional folk song “Man of Constant Sorrow”

The Françoise Hardy All Over the World website cites Peter, Paul & Mary’s “Sorrow” as the source for “Il Est Trop Loin.” I’m not so sure about that. As “Man of Constant Sorrow,” the song has been recorded by many artists, including (on his first LP) Bob Dylan, an artist of whom Hardy was certainly aware (and had personally met when he played Paris on his 1966 European tour). Other songs have varied the title and lyrics, as Judy Collins did on “Maid of Constant Sorrow.” While Peter Yarrow and Noel “Paul” Stookey were credited as the writers when it appeared as simply “Sorrow” on Peter, Paul & Mary’s first album in 1962, that track was the same as the song—usually described as a traditional folk song—that had appeared as “Man of Constant Sorrow” and other variants. It would have been more proper to credit them as arrangers rather than writers.

Wherever she first heard it, it’s not surprising that Hardy was attracted to a bittersweet folky song with sorrow as its main motif. She did little that could be classified as straight-up “folk-rock,” but “Il Est Trop Loin” comes close, with a jangly circular guitar riff and just-barely-there bass and drums. After almost two minutes, of course, an orchestra enters to alter the mood, followed by ethereal backup vocals. It would have been less predictable, and perhaps more interesting, to let this play out as low-key folk-rock the whole way through instead of bowing to the Françoise formula of sorts. The guitar does solo for an uncommonly long time near the end, for a Hardy track at any rate.

It’s hard to call this a “superior” cover considering both that it’s unclear what her source was, and that there are so many other versions of this standard. But it’s still a worthy, somewhat unusual interpretation of this oft-covered (some would say over-covered) song, and certainly one of her more unusual late-‘60s recordings, both in its arrangement and her choice of material to reconfigure.

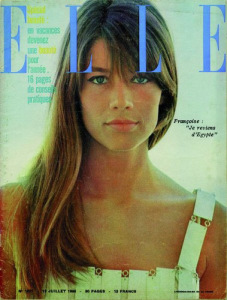

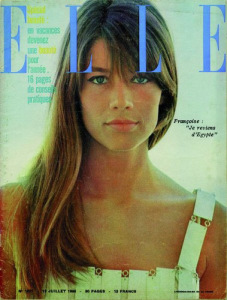

Elle magazine cover

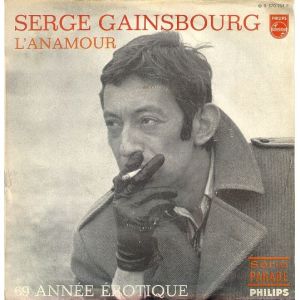

Comment te Dire Adieu (French LP Françoise Hardy, 1968; titled Comment te Dire Adieu on CD reissue)

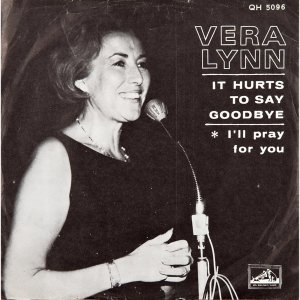

Original version: by Vera Lynn (as “It Hurts to Say Goodbye”), 1967, or Arnold Goland (as “It Hurts to Say Goodbye”) circa 1967

Vera Lynn was one of the most popular British singers of the pre-rock era, and made the UK and even US charts into the late 1950s. These days, she might be most remembered for songs associated with the Allies’ World War II effort: “We’ll Meet Again,” “The White Cliffs of Dover,” and “There’ll Always Be an England.” But she had plenty of other British hits in the 1940s and 1950s, and even had a fair amount of success in the US, where “You Can’t Be True Dear” made the Top Ten in 1948, and “Auf Wiederseh’n Sweetheart” went all the way to #1 in 1952.

In 1967, Lynn—by then 50 years of age—had a last chart hurrah of sorts when “It Hurts to Say Goodbye” made the Top Ten of the Easy Listening charts. Although it’s in some ways the relic of an era that rock had superseded, it’s actually a pretty impressive and powerful ballad, with an impassioned vocal, grand cinematic orchestration, and a bittersweet melody to complement the lyric of regretful parting. The opening in particular can’t help but recall the bombastic burst of strings and voices that kicked off Dusty Springfield’s 1966 smash “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me,” if rock-oriented listeners (and I am one) need a point of reference.

This could have been a version Hardy heard, but there was an earlier one by American singer Margaret Whiting on her 1966 LP The Wheel of Hurt. Although it’s not too much different than Lynn’s cover (and a tad more rock-influenced in the arrangement), it’s considerably less memorable. It’s just not nearly as over-the-top, vocally or instrumentally, as Lynn’s (to its credit) was. Virtually forgotten today, Whiting had been recording jazz, pop, country, and easy listening since the 1940s, and had a couple #1 hits in the late ‘40s with “A Tree in the Meadow” and “Slippin’ Around.” And she wasn’t totally off the scene by the mid-‘60s, landing a #26 single in late 1966 with “The Wheel of Hurt,” which topped the US easy listening charts.

Hardy’s French-language cover, “Comment te Dire Adieu” (whose lyrics were supplied by legendary French singer-songwriter Serge Gainsbourg), was really different than either of these predecessors—almost radically so. Where Lynn (and Whiting, if you want to include her in the discussion) had played up the staunch sadness of parting from a loved one, Françoise—unusually, even shockingly, given her track record—lightened things up, instead of retaining or even accentuating the melancholy.

“Comment te Dire Adieu” is not just upbeat—it’s downright jaunty, with a light swing and pseudo-Herb Albert trumpet that almost puts it in bachelor pad music territory. The vocal’s teasingly playful, almost as if Hardy’s joyful at being set free, rather than tearful at being torn apart. The slightly ominous rock-ish downward-descending riff at the end of the verses isn’t found at all in Lynn’s version; nor are the super-sexy spoken passages in the bridges. Note that the French title translates to “How to Say Goodbye,” not “It Hurts to Say Goodbye,” perhaps accounting in part for the less sorrowful tone.

All this combines to make “Comment te Dire Adieu” one of Hardy’s most interesting covers, and certainly one of the covers that differed most from its model. It’s hard to compare such different arrangements, which makes it something of a tie between Hardy and Lynn for quality, or a case where you should choose the one you play depending on your mood.

A few months after I first put up this post, reader Magnus Astrom chimed in with some useful information. “When it came to her source of ‘It Hurts to Say Goodbye’ [Françoise] has said herself in numerous interviews that she heard it at an editor as an instrumental,” Magnus wrote. “Apparently this person had booked a meeting with her to present her with, what he considered, suitable songs for her. And of all the songs he played her she liked none, with the possible exception of an instrumental that she took almost only so that the whole session shouldn’t have been a total waste of time. Listening to it again at home, she found that it started to grow on her. Then her secretary suggested that they should ask Serge Gainsbourg to write lyrics for it. Which, to Françoise’s surprise, he agreed to do.”

The new lyrics by Gainsbourg could in themselves account in part for the more upbeat tone of Hardy’s version. More crucially, however, this indicates that Hardy might have heard the instrumental version that one of the two composers of the original “It Hurts to Say Goodbye,” Arnold Goland, issued on a single circa 1967. The arrangement is extremely similar to the one on Hardy’s “Comment te Dire Adieu”—so much so, however, that the possibility can’t be discounted that it’s based on Hardy’s version, not the other way around.

Further complicating matters, as Magnus points out, “Some fan discussion claims that this single was cancelled – https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/spectropop/conversations/topics/47367.” What’s more, the other co-writer of the original “It Hurts to Say Goodbye,” Jack Gold, also put out a version (in 1969). But as Magnus observes, “This version features a choir singing the lyrics so it can’t be the source version. And it’s too late, only appearing after her version.”

While Hardy disparages much of her early work in her memoir The Despair of Monkeys and Other Trifles (published in English in 2018), and supplies surprisingly scant detail about her ’60s records in the book, she does comment at length on how “Comment Te Dire Adieu” evolved. “Sometime in the year 1968, a music producer invited me to come to his office to listen to a selection of tunes composed for me,” she writes. “I spent an entire afternoon with him without a single melody clicking. I felt just like how I feel when I’ve been in a boutique for some time and dare not leave empty-handed to avoid feeling guilty for getting the sales clerk worked up for nothing.

“Although it was the producer who had invited me, not vice-versa, in desperation I asked him to let me take a copy of one American instrumental that was less gloomy than all the rest—its title was ‘It Hurts to Say Goodbye.’ When I returned home, I felt obliged to listen to it again and, against all expectation, immediately felt the click. This piece of music seemed to stand out miraculously from the pack.

“[Agent] Lionel Roc suggested I ask Serge Gainsbourg to write the lyrics for it. He had not sold a lot of records yet but had written songs for, among others, France Gall [and] Juliette Greco. In fact, his standing was so high that most singers dreamed of covering one of his songs. I objected that Serge only wrote lyrics for his own tunes, but Lionel insisted and a meeting was arranged…He telephoned me several weeks later at the Savoy [Hotel] and read the opening part of ‘Comment te dire adieu’ (‘How Do I Tell You Goodbye?’) before coming to London to show me the rest of the song.”

Parlez-Moi de Lui (French LP Françoise Hardy, 1968; titled Comment te Dire Adieu on CD reissue)

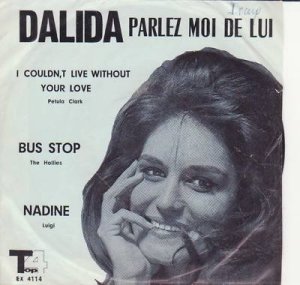

Original version: by Kathy Kirby (as “The Way of Love”), 1965, and/or Dalida, 1966

Most, though not all, of the 1968 French album simply titled (as were, confusingly, several of her other 1960s French LPs) Françoise Hardy was devoted to songs by other composers, some of which had been previously released by other artists, some not. In my view—and with so many Françoise fans, there are bound to be many who disagree—this record showed her slipping distressingly further into less interesting middle-of-the-road pop. If that’s what she wanted to explore, however, “Parlez-Moi de Lui” was certainly the right kind of source material.

The song had first been recorded as “The Way of Love” by British singer Kathy Kirby in 1965. Kirby had a bunch of UK hits between mid-1963 and mid-1964, but was rapidly passing out of fashion as the tougher sounds of the British Invasion overwhelmed first her home country and then the globe. “The Way of Love” wasn’t just tamer than the Beatles or the Stones; it wasn’t even rock, and not even a particularly strong mainstream pop ballad. Or even sung with that much distinction, though the orchestra gave it their all when they entered the proceedings, crashing in with the subtlety of a tree falling through the roof. Unusually, though Kirby’s single missed the UK charts entirely, it did make a ripple across the Atlantic, peaking at #88 in the US (where it was her only 45 to enter the Top 100).

It seems possible, and maybe even likely, that Hardy was also—or even only—familiar with a French-language cover by Italian woman singer Dalida in 1966. Titled (like Hardy’s own interpretation) “Parlez-Moi de Lui,” it outdid Kirby’s original on every level. That didn’t change it into a great song, but her vocal was far more effectively sultry, in addition to just plain having lots more horsepower. The orchestra played harder and louder too, especially at the de rigueur pull-out-the-stops soaring finale.

Hardy’s take on this tune is quite different to Dalida’s or Kirby’s. It’s no shock that she gives it a much quieter, more thoughtful vocal, though the orchestra and choral backup vocals still make their entrances as if on cue. But the backing is more understated—if only just—than those on the prior versions as well, making it more different to the prototypes than most of the songs she covered in the ‘60s. Too bad it’s one of the least memorable of the songs she chose to interpret, however, when all’s said and done. For what it’s worth Dalida’s version might be better, as her style is more of a match for the material.

La Mésange (French LP Françoise Hardy, 1968; titled Comment te Dire Adieu on CD reissue)

Original version: Quarteto em Cy & MB-4 (as “Sabia”), 1968, and/or Cynara & Cybele, 1968

The first sign of Hardy’s growing interest in Brazilian pop and bossa nova was her cover of “Sabia,” co-written by one of bossa nova’s giants, Antonio Carlos Jobim. Recordings of “Sabia” from 1968 by both Quarteto em Cy & MB-4 and Cynara & Cybele have been cited as the inspiration for her French-language version. I haven’t been able to find one by Cynara & Cybele, but did locate the rendition by Quarteto em Cy & MB-4.

I confess I’m not the biggest bossa nova or Jobim fan, and Quarteto em Cy & MB-4’s “Sabia” didn’t impress me much. It’s a very lushly produced track, suffused with strings and interwoven harmonizing vocals by both male and female singers. The melody’s relatively complex and winding, but ultimately not too memorable to me.

You can tell I don’t have as much to say about this song as most of the previous items in this post, and I don’t have too much to say about Hardy’s cover either. It’s also overproduced, with too many strings, though not quite as overcooked as the Quarteto em CY & MB-4 version. I do prefer hearing her solo lilting vocals, as opposed to Quarteto em CY & MB’s multi-layered harmony vocals, which (like some others on vintage bossa nova records) have a jazz-choral-pop feel that’s not to my taste.

Où Va La Chance? (French LP Françoise Hardy, 1968; titled Comment te Dire Adieu on CD reissue)

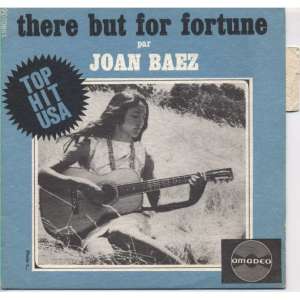

Original version: Joan Baez (as “There But For Fortune”), 1965; and/or Phil Ochs, 1966

Although Hardy was drifting into more middle-of-the-road pop in the late 1960s, that doesn’t mean she wasn’t aware of hipper British and American sounds than, say, Kathy Kirby’s “The Way of Love.” A couple selections on her 1968 Françoise Hardy LP indicated she was paying attention to folky singer-songwriters as well. One was her take on “There But for Fortune,” one of the most outstanding early compositions of Phil Ochs, the best socially conscious folk singer-songwriter on the mid-‘60s scene other than Bob Dylan. While “There But for Fortune” didn’t totally evade the protest/social commentary field, it was also one of his first songs to add a non-social-specific sense of poetry to his lyrics, complementing the wistful melody.

Before Ochs put out his own version on his 1966 In Concert album, Joan Baez had a small hit single with the song in the US, where it reached #50 in late 1965. (In fact, it was her biggest single of the 1960s, though of course she had numerous big hit LPs during that decade.) Baez’s cover was a much bigger hit in the UK, where it reached #8. It seems likely her version was the one Hardy heard first and most often, though it’s possible she also heard the one in 1967 by Michèle Arnaud, original performer of another song Françoise covered, “Ma Jeunesse Fout L’Camp.” Arnaud also used the same French translation for the lyrics (by Eddie Marnay) that Hardy did, retitling the song (again, as Hardy did) “Où Va La Chance?”

Hardy’s “Où Va La Chance?” has, unlike the plain folk of Baez and Ochs’s prototypes, an overtly baroque arrangement, dominated by harp (as in the instrument with plucked strings, not the harmonica). Light drums are added before the expected addition of orchestration after a minute-and-a-half or so. Her cover’s okay, but not a match for Ochs’s. And while Hardy’s coolly measured phrasing often worked to curb the excesses of the melodramatic material she often interpreted, here’s one case where the more committed and nuanced singing of Ochs works better.

Ochs never had hit singles (or very high-charting LPs) on his own, and there were no hit covers of his songs other than Baez’s “There But for Fortune.” So one would have to think that its placement on a Françoise Hardy LP was actually one of his bigger money-earners, if the publishing revenues got to him.

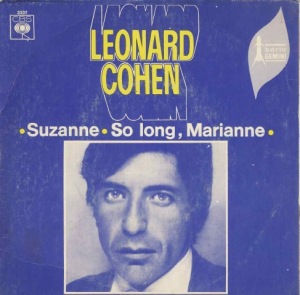

Suzanne (French LP Françoise Hardy, 1968; titled Comment te Dire Adieu on CD reissue)

Original version: Leonard Cohen, 1967, and/or Judy Collins, 1966

Although Hardy was one of the earlier artists to cover a Leonard Cohen song, she was hardly the first, or even the first to do one of his most famous works, “Suzanne.” First on that score was Judy Collins, who put “Suzanne” (and another Cohen composition, “Dress Rehearsal Rag”) on her In My Life LP in late 1966, about a year before Cohen’s own version came out on his debut album. The first artist of any kind (let alone a renowned one) to interpret Cohen’s songs, Collins put a few more on her next LP, 1967’s Wildflowers. And in late 1967, Noel Harrison had a small US hit with “Suzanne,” while in the UK, Fairport Convention did a great folk-rock version on the BBC in September 1968, though they didn’t put it on any of their studio releases.

While Collins might have been more responsible than anyone else for pioneering the “baroque folk” genre—folk, and a bit of rock, dressed up with orchestration—her rendition of “Suzanne” actually only uses acoustic guitar and bass. Hardy, unsurprisingly, goes the all-out baroque route. Like “There But Fortune,” it’s okay, but not a match for the prototypes by either Collins or Cohen. Unusually, it uses multi-tracked vocals, which does set it a bit apart from her average ‘60s recording.

It’s also indicative of a challenge she faced as she began to do material by fairly well-known singer-songwriters other than herself. Though her choice of songs often testified to her good taste, by taking on artists who were much were well known than, say, the Joys or Samantha Jones, she was inviting far more unfavorable comparisons to the originals. And by taking on artists with a much more formidable body of work than the Joys or Samantha Jones, she would find it hard to match the quality of or inventively reshape those originals.

La Rue Des Coeurs Perdus (French LP Françoise Hardy, 1968; titled Comment te Dire Adieu on CD reissue)

Original version: Ricky Nelson (as “Lonesome Town”), 1958

Early American rock’n’roll was a big (if hardly the only) influence on Hardy, but it wasn’t until the late 1960s that she covered well-known early rock’n’roll classics. Actually, while “Lonesome Town” was a big hit for an early rock’n’roll star (Ricky Nelson), it wasn’t exactly rock’n’roll even in its first incarnation. This 1958 Top Ten hit was a lovelorn acoustic ballad with ghostly backing vocals and something of a cowboy western feel, like the song of heartbreak the leading man would sing as he rode his horse out of the town he’d just rescued. It wasn’t exactly typical of Nelson’s early hits, but it was very good, haunting, and effective.

And, one would think, it would be an appropriate song for Hardy to cover, should she want to cover any big early rock’n’roll hits at all. Alas, this not only proves not to be the case. Instead, her arrangement is swamped with strings, and set to a modified country-and-western beat, complete with barroom-tinged piano. The swell of background voices at the end, as if to bring down the curtain on a number in a musical, is especially disheartening. As much as she excelled at melancholy songs of heartbreak, here she sounds innocent and chipper, failing to project the genuine forlorn desolation that Nelson did—and quite well—in his hit original.

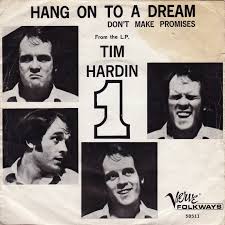

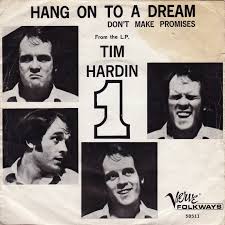

Hang on to a Dream (UK LP En Anglais, 1968)

Original version: Tim Hardin (as “How Can We Hang on to a Dream”), 1966

Although Hardy’s all-English-language album En Anglais was disappointing (more details a few entries down), there were a few tracks that stood out from the rest, both for their higher quality and for the greater obscurity of the sources. One was “Hang on to a Dream,” which had featured on Tim Hardin’s 1966 debut LP. It could be expected that Hardy would have an affinity with Hardin, another singer-songwriter who favored darkly bittersweet, introspective moods. Hardin wasn’t exactly obscure, but he wasn’t a big star either, or even as big as Leonard Cohen, though Bobby Darin had taken Hardin’s “If I Were a Carpenter” into the Top Ten in late 1966.

Hardy’s treatment of the song is fairly different from Hardin’s, if not too different from how she usually handled such material. Gothic backup vocals at the very opening (which recur throughout the track) make it evident it’s going to be gaudier than Hardin’s original, and understated orchestration also pushes this from folk-rock to baroque folk. It’s those gloomy backup vocals, however, that do the most to differ this from Hardin’s prototype, accentuating the song’s desperation. While it doesn’t equal the original (or, for that matter, Ian & Sylvia’s less ornate folk-rock cover on their 1967 Loving Sound album), she handles the vocals in a nicely sweet-but-sad manner too.

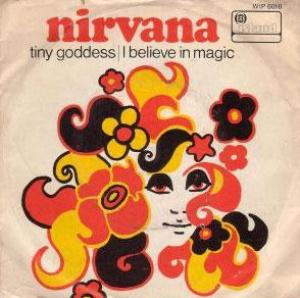

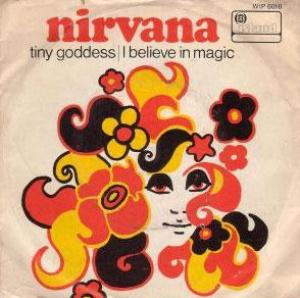

Tiny Goddess (UK LP En Anglais, 1968)

Original version: Nirvana, 1967

The British ‘60s band Nirvana—no relation, of course, to the Seattle grunge stars of the ‘90—had just one low-charting single (“Rainbow Chaser,” #34, 1968) in the UK, though they garnered a cult following many years later with their brand of delicate baroque-pop-psychedelia. “Tiny Goddess” was their first single, combining harpsichord, cello, and hushed female backup vocals in its gently flower-power-styled portrait of the song’s subject.

It’s a little surprising that Hardy found the song, but then, she’d been sniffing out flop singles and little-known foreign sides for her entire career. It has a more orchestral arrangement than the original—I know, what a shock—but otherwise differs less from the Nirvana version than most of her covers. Her typically cool and collected, less-is-more delivery is a good fit for the tune, and like “Hang on to a Dream,” it’s far superior to the other covers on En Anglais.

As a reader notes in the comments section, “It’s possible that FH found ‘Tiny Goddess’ via the ’67 recording of the Jackpots, a popular band in Sweden. I also recall someone saying Nirvana’s recording got considerable play on pirate radio stations in the Channel.”

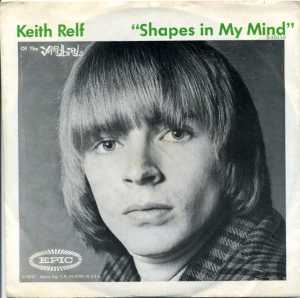

Empty Sunday (UK LP En Anglais, 1968)

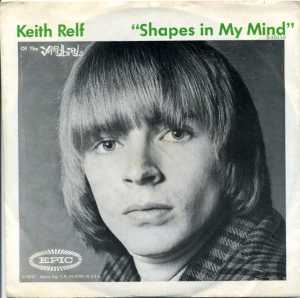

Original version: Keith Relf (as “Shapes in My Mind”), 1966

This peculiar track only counts as a half-cover, perhaps. For the verses of “Empty Sunday” are acceptable, if hardly exceptional, slightly glum pop-rock with a Continental flavor. Yardbirds fans ears will instantly perk up, however, when Hardy sings the bridges, which are taken note-for-note and word-for-word from the bridges of Keith Relf’s flop 1966 single “Shapes in My Mind.”

“Empty Sunday” was written by famed British music entrepreneur Simon Napier-Bell and Ready Steady Go assistant producer (and Dusty Springfield manager) Vicki Wickham. The pair collaborated on a few songs in the 1960s, most famously Dusty Springfield’s 1966 megahit “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me.” They co-wrote the English lyrics to Springfield’s version when it was adapted from the Italian original, “Io Che Non Vivo (Senza Te)” (a big 1965 hit in Italy for one of the original co-writers, Pino Donaggio).

In 1966 Napier-Bell became the Yardbirds’ manager. Though his stint was relatively brief, it did take in the even briefer attempt to launch a sideline solo career for their singer, Keith Relf. That was pretty much a bust, and Relf’s second and final 45 while with the Yardbirds, “Shapes in My Mind” (actually released in two different versions, one starting with organ, another with sax and bass) was a flop. It’s a pretty cool, unusual moody song with a baroque-pop flavor and unusual tempo changes, moving from tango-like verses to more insistently pounding bridges. Those bridges were recycled for the otherwise unrelated “Empty Sunday,” Hardy faithfully using the same rhythm.

This was not, incidentally, the only instance in which Napier-Bell wrote for Françoise. With his chum Vicki Wickham, he also wrote “Never Learn to Cry,” which with more tweaking from Hardy became “Mon Monde N’est Pas Vrai,” a track on her 1970 album Soleil.

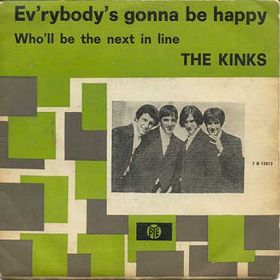

Let It Be Me; Loving You; That’ll Be the Day; Who’ll Be the Next in Line; Will You Love Me Tomorrow (UK LP En Anglais, 1968)

Original versions: The Everly Brothers, 1960; Elvis Presley, 1957; Buddy Holly, 1957; The Kinks, 1965; The Shirelles, 1960

Some fans will find it heresy—indeed, be outraged—to have these five songs from En Anglais grouped into one entry and, essentially, dismissed. Nonetheless, it’s my feeling that Hardy’s covers of these are A) not very good, and B) not worthy of extended individual comment.

As noted in the entry on “Lonesome Town,” early rock’n’roll was a big formative influence on Françoise. So it made sense that she’d want to pay homage to Elvis, Buddy Holly, the Shirelles, and the Everly Brothers (who didn’t do the first version of “Let It Be Me,” but probably did the one that inspired Hardy, an Everlys fan). But it wasn’t going to be easy—indeed, it wasn’t going to be possible—to equal the originals. She did put different arrangements to them, but they were fairly disastrous, drenching them in strings and generally removing their considerable edge, even on the Everlys and Elvis ballads. If the strategy was to aim somewhere between the US easy listening and country-pop markets, she succeeded, but it’s hard to imagine either easy listening or country-pop listeners taking much of a shine to these pretty dreary interpretations. And as much as she might have loved early rock’n’roll, she simply wasn’t capable of summoning the raucous energy necessary to sing it (or certainly sing “That’ll Be the Day”) with any effectiveness.

That problem becomes more acute on “Who’ll Be the Next in Line,” which actually was much better known in the US (where it became a Top Forty hit) than the Kinks’ UK homeland (where it was only a B-side). Like many early Ray Davies songs, “Who’ll Be the Next in Line” was almost punky in its raw raunch. Hardy’s arrangement is not only tamer (especially in the vocal department, including double-tracked ones on the bridge), but afflicted by soaring strings that are wholly at odds with the song’s spirit and thrust. Where Davies sneered the words with genuine hurt, Hardy enunciates them with all the congenial neutrality of someone waiting in line for a sandwich at the cafeteria.

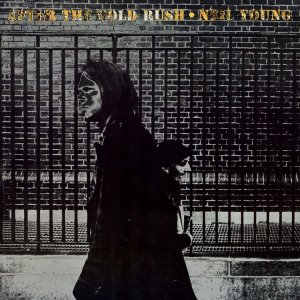

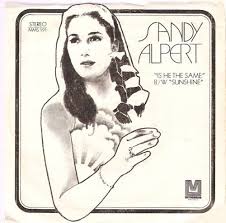

Soleil (French LP Soleil, 1970)

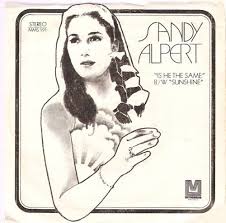

The title song for Hardy’s 1970 LP Soleil has a source so obscure I didn’t become aware of it until more than a year after I originally posted this article. American singer-songwriter Sandy Alpert co-wrote the English-language original, “Sunshine,” with Tash Howard, who also produced Alpert’s original version. This seems to have appeared on a radio-only promo 1970 single and a Spanish 45.

The arranger for Alpert’s version was Jimmy Wisner, who worked with many hit artists. He also got a Top Ten hit record of his own (under the pseudonym Kokomo) in 1961 with the instrumental “Asia Minor,” a rocked-up rendition of Grieg’s classical piece “Piano Concerto in A Minor.” Wisner also co-wrote the 1963 Orlons B-side “Don’t Throw Your Love Away,” which was covered for an early British Invasion hit by the Searchers the following year.

Hardy’s version isn’t too different from Alpert’s, and is one of the more faithful of her covers to the original arrangement. Hardy even replicates the double-tracked vocals on the chorus from Alpert’s single. Alpert’s 45 might be more lushly orchestrated, Françoise’s employing, as was her wont, more acoustic guitar.

Overall, however, this is one of the closest Hardy’s covers comes to scoring as more or less a tie with the original. She also sang the English-language version, “Sunshine,” on a 1970 English-language LP (titled Alone in the US), using the same backing track. On this English version, Françoise omits one verse and, more oddly, sings “some day” instead of the “amen” heard at the end of the choruses in the original.

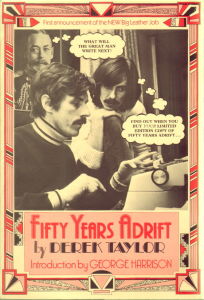

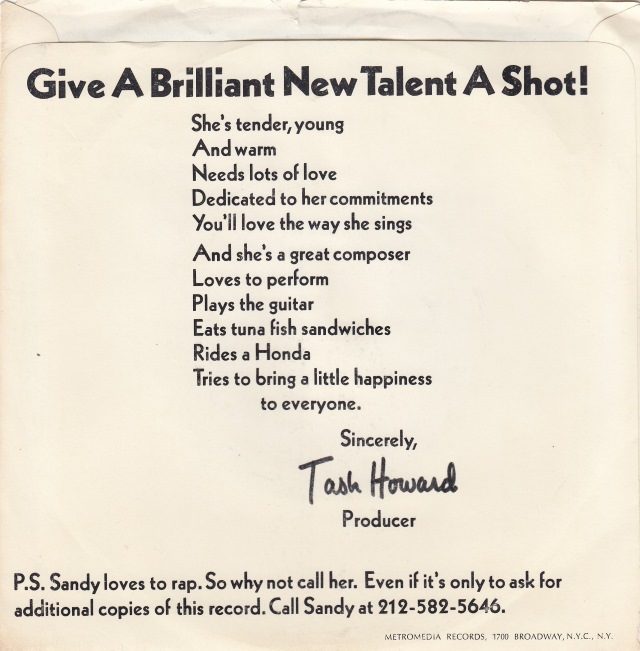

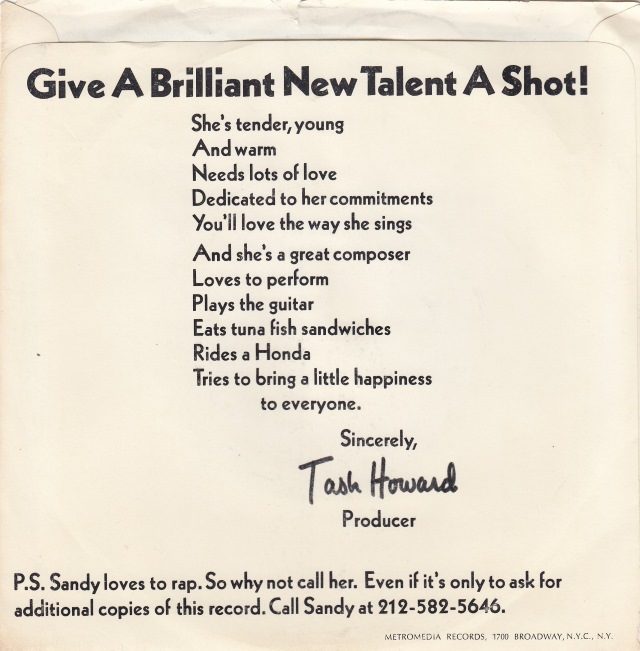

Sandy Alpert’s original single on Metromedia even had a picture sleeve (see below). It seems doubtful it made it into the stores, however, as the back cover is entirely given over to a rather tacky message poem by producer Tash Howard. “Give A Brilliant New talent A Shot!” it proclaims. “She’s tender, young, and warm. Needs lots of love. Dedicated to her commitents. You’ll love the way she sings. And she’s a great composer. Loves to perform. Plays the guitar. Eats tuna fish sandwiches. Rides a Honda. Tries to bring a little happiness to everyone.”

The strongest indication that this might be a promo-only release is the “P.S.” Howard adds at the bottom: “Sandy loves to rap. So why not call her. Even if it’s only to ask for additional copies of this record. Call Sandy at 212-582-5646.” Printing the personal phone number of the artist and encouraging requests for giveaways is not the standard practice for commercial singles, to say the least, and quite likely not even for promo 45s.

Considering the obscurity of the original version, one wonders how it made its way to Hardy. Quite possibly she heard a demo. Maybe this very 45 was the demo she and/or her associates was sent. It’s hard to imagine her or anyone else she worked with stumbling across it in a shop.