When you teach a course on the Rolling Stones, as I’ve done three times now for a couple adult-education programs, you talk a lot about their influences. As the Stones covered so many songs by other artists in the 1960s, that often means discussing and playing some tunes they interpreted. Even for someone like me who’s been a fan for forty-five years or so, that leads you to think about and listen to some things that haven’t crossed your mind for a long time, and even to hear and learn some new stuff.

This compilation of songs the Rolling Stones covered was given away with the August 2012 issue of Mojo magazine.

Of the dozens of songs they covered (especially when you count demos, outtakes, and BBC sessions), it’s now struck me that there are a few instances where the Stones probably didn’t hear the original version, learning the material from an actual cover by someone else. This isn’t that rare; the Beatles, for instance, almost certainly learned “I Got to Find My Baby” (which they did twice on the BBC in 1963) from Chuck Berry’s 1960 recording, not the early-1940s original by Doctor Clayton (or even Little Walter’s 1954 version), as you can read about in one of my earlier blogposts. Elvis Presley’s “Hound Dog” was based not so much on the Big Mama Thornton original (which he was aware of) as a crass Bill Haley-like 1955 cover by early, now-almost-forgotten rock’n’roll group Freddie Bell and the Bell Boys. There must be countless other examples.

Of the covers the Rolling Stones placed on their official recordings (and even counting the high-quality unofficial ones), it strikes me that there are five that they likely learned from covers, rather than the originals. One of them is perhaps their most commercially successful cover version; another is perhaps the most obscure cover they placed on one of their albums. The three others have less interesting paths to the band, probably coming in all cases via their single biggest influence, Chuck Berry. Let’s start with the most obscure such item, Robert Wilkins’s “Prodigal Son,” which appeared on their 1968 album Beggars Banquet.

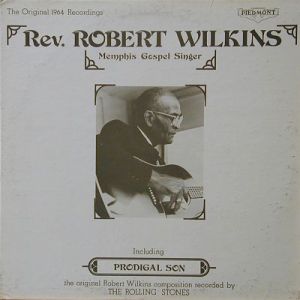

After the Stones covered “Prodigal Son,” this Robert Wilkins LP was reissued to hype that fact on its cover.

As has often been stated by historians, Beggars Banquet marked a return by the Stones to a much bluesier sound than they’d favored since starting to write the bulk of their own repertoire around 1965 (and certainly a much bluesier sound than they’d gone for on their 1967 psychedelic LP, Their Satanic Majesties Request). While the band had occasionally gone into acoustic blues of the pre-World War II variety (as on the early Mick Jagger-Keith Richards composition “Good Times, Bad Times,” used on the 1964 B-side of “It’s All Over Now”), Beggars Banquet also went into more Delta-style acoustic blues than any of their previous releases.

All of the Stones would have known something about the form, but the biggest kick in this direction was probably supplied by Keith Richards, who told Guitar Player in 1977, “During that long recording layoff after [the 1967 album] Between the Buttons, I got rather bored with what I was playing on guitar—maybe because we weren’t working, and it was part of that frustration of stopping after all those years and suddenly having nothing to do. So my playing sort of stopped, along with me. Then I started looking into some Twenties and Thirties blues records. Slowly, I began to realize that a lot of them were in very strange tunings.”

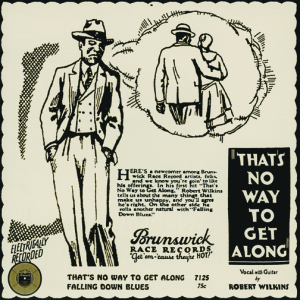

This might have been a time when he listened to Robert Wilkins, who made his first body of recordings between 1928 and 1936. One of those recordings (performed in 1929) was “That’s No Way to Get Along,” which musically is nearly identical to the song Wilkins would later—much later—record as “Prodigal Son.” Lyrically, however, it’s totally different. Where “Prodigal Son” is almost a narrative of a, well, prodigal son, “That’s No Way to Get Along” has very basic words about being treated bad by low-down women; crying and falling into self-pity as a result; and telling the basic tale to his mama. The only strong lyrical similarity to “Prodigal Son,” in fact, is in the title phrase “That’s No Way to Get Along,” which is repeated with some variations at the end of the verses.

Like many of the Delta bluesmen who recorded in the ‘20s and ‘30s, Wilkins was rediscovered during the folk revival of the early-to-mid-‘60s, relaunching a recording and performing career after decades without any discs. In the intervening years he’d become much more religious, in both his life and his music. He was now playing a sort of blues-gospel, reworking “That’s No Way to Get Along” with biblical lyrics. The result was “Prodigal Son,” a ten-minute epic where “That’s No Way to Get Along” had lasted just shy of three.

It’s been reported that the Stones learned, or based their version of, “Prodigal Son” on Wilkins’s version on the compilation The Blues at Newport 1964 Part 2, recorded at the Newport Folk Festival in July 1964. That would make sense; Newport was the biggest folk festival of the time, and the albums recorded there were pretty widely heard by folk and blues fans. It’s also possible, however, that they heard it first, or also heard, the version Wilkins recorded in the studio slightly earlier (in February 1964) for the Piedmont Records LP Reverend Robert Wilkins—Memphis Gospel Singer. By 1964 the Stones were going to the US and had a lot more money than they’d ever had before. It certainly wouldn’t be surprising if Richards and/or some other guys in the band found the Piedmont album in an American record store, or even in a London store that imported folk and blues LPs; Dobell’s, on Charing Cross Road in Central London, was especially known for doing so.

The two 1964 versions are pretty similar, but no matter which one you hear (and both are pretty accessible now), it’s interesting how much the Stones condensed the lyrics. The Stones almost certainly wouldn’t have considering putting a ten-minute blues cover of any kind on a 1968 LP, and knocked “Prodigal Son” down to three minutes, mostly by eliminating a lot of repetition—cutting to the chase, almost. Where Wilkins made whole verses out of singing the same line over and over, Mick Jagger combined the lines into verses. Nonetheless, it’s often still not all that easy to make out the words he’s singing.

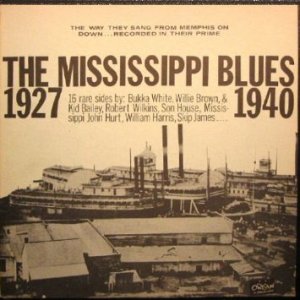

Were the Stones even aware that “Prodigal Son” had evolved from the 1929 Wilkins recording of “That’s No Way to Get Along”? Possibly not; in the late 1960s, early blues records weren’t nearly as easy to get (or hear) as they are now. Yet they quite possibly were aware of “That’s No Way to Get Along,” as it had been reissued in 1963 on the Origin Jazz Library compilation LP Mississippi Blues 1927-1940—not exactly common fare at most record stores, but almost certainly in the bins at some record stores the Stones visited.

A more intriguing question is: were the Rolling Stones aware that Wilkins had, in 1928, recorded a number titled “Rolling Stone Blues” (in parts 1 and 2, no less)? It’s pretty well known that the Rolling Stones named themselves after a Muddy Waters song titled “Rollin’ Stone,” first issued on a 1950 single. Here’s guessing, however, that they hadn’t heard “Rolling Stone Blues,” which in 1962 was very hard to find or hear, especially in the UK. It wouldn’t even get reissued until the 1967 compilation Mississippi Blues Vol. 1 (1927-1942). The term “rolling stone” had already been in slang use by the time Wilkins recorded “Rolling Stone Blues,” but that might well be the first time it was used in a blues song.

As a final footnote to the “Prodigal Son” saga, the song was mistakenly listed as a Jagger-Richards composition when Beggars Banquet was first released. This was changed on future editions, this fine March 1, 1969 Rolling Stone article by Tony Glover (of the US blues-folk act Koerner, Ray & Glover) detailing how the matter was brought to the attention of the group and their record label. Wilkins, stated Peter Kuyendall (who owned the song rights) in the piece, “seemed quite happy that people will be hearing his song. It couldn’t bother him that a rock group has done it.”

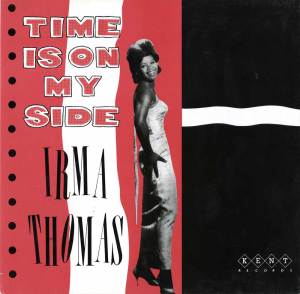

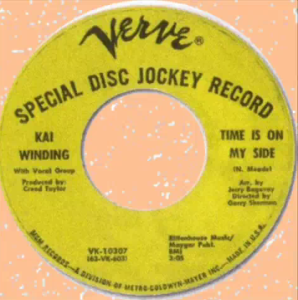

If “Prodigal Son” was one of the more obscure covers the Rolling Stones released, “Time Is On My Side” was arguably the most famous. Certainly that’s the case in the US, where it became the band’s first Top Ten hit in late 1964 (though it wasn’t released as a single in their native UK, where a cover of “Little Red Rooster” was issued instead, making #1 in the British charts). The group learned the song from New Orleans soul singer Irma Thomas’s more gospel-flavored version. But Thomas’s rendition, as good as it was, wasn’t the original. The original, rather weirdly, was by famed jazz trombonist Kai Winding, who put it out as a single on Verve Records in October 1963.

Though the vocals on Kai Winding’s version of “Time Is On My Side” were handled by well-known soul singers, they were only credited as “Vocal Group” on the label.

The choice of material wasn’t as strange as it might first appear. In an era where off-the-wall instrumental hit singles were not uncommon, Winding had scored one a few months earlier with “More.” In truth, that hit was more memorable for the lines played by Jean-Jacques Perry on the Ondioline (which sounded like a high-pitched, keening organ) than it was for Winding’s low-profile trombone. But when it came time for a follow-up that might likewise make the pop charts, songwriter-producer Jerry Ragovoy was contacted. He passed on one of his compositions, “Time Is On My Side.” (Ragovoy would become most famous for co-writing the soul songs “Piece of My Heart,” “Try (Just a Little Bit Harder),” “Get It While You Can,” and “My Baby,” all of which were covered by Janis Joplin.)

After being used to the Stones’ version for fifty years, it’s a shock to hear Winding’s single. The melody is all there, and are the words to the chorus and the parts of the verse where the title is sung. But nothing else is there word-wise, the singers credited only as “vocal group” on the 45 oohing wordlessly as Winding plays trombone. It’s as if they’ve recorded everything for a full vocal number, but simply forgotten to dub or punch in those parts of the verses (and there’s no spoken rap in the middle, that being an instrumental break again dominated by trombone). For all its incomplete feel, the “vocal group” really wails with soul near the end. And no wonder – the group were top New York session singers Dionne Warwick (actually by then a star), her sister Dee Dee Warwick, and Cissy Houston (mother of Whitney).

The missing words weren’t a mistake. Ragovoy simply hadn’t written any. In a way, it’s like numerous easy listening arrangements of popular hits in the 1960s, where those pesky verses were ignored, the anonymous session singers only bothering with the title and chorus. The strategy was employed on numerous early reggae covers of British and American hits too. If nothing else, it must have saved on the typesetting bills for the lyric sheets used at the recording sessions.

In most respects, however, Kai Winding’s arrangement is fairly similar to the one used on Irma Thomas’s cover. When she did her version in 1964, however, the verses were filled in with more lyrics, as was the instrumental break (with a spoken rap). Those words were devised by Jimmy Norman, which is why the writing credits are for Norman Meade and Jimmy Norman. But who’s that Norman Meade? That’s a pseudonym for Jerry Ragovoy. Got all that? And when the Stones covered Thomas’s cover, a near-instrumental for a jazz trombonist somehow became a British Invasion hit for a blues-rock band.

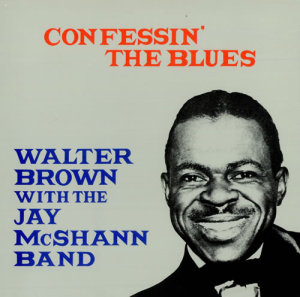

The last few cases in which the Rolling Stones probably didn’t hear the original aren’t as interesting as “Prodigal Son” and “Time Is On My Side,” but still worth noting. “Confessin’ the Blues,” on their second US LP 12 X 5 in 1964 (and also on the UK EP 5 X 5 that year), is a fairly slow and standard blues that’s one of their less celebrated early tracks. It was first done as a piano-dominated shuffle way back in 1941 by jazz-blues pianist Jay McShann, with Walter Brown on vocals. Chuck Berry did a peppier blues-rockin’ version on his 1960 album Rockin’ at the Hops, which had no less than three other songs the Stones would record: “Bye Bye Johnny,” “Down the Road Apiece,” and “Let It Rock.” (Not to mention “I Got to Find My Baby,” which as noted earlier was done by the Beatles on the BBC.)

One would think the Stones would be far, far more likely to be familiar with Berry’s version than McShann’s. In his fine 1976 disc-oriented career overview The Rolling Stones: An Illustrated Record, Roy Carr doesn’t seem to think so, noting that “surprisingly, the Stones keep to McShann’s slower interpretation.” My guess is, however, that the Stones did base their version on Berry’s, simply slowing the tempo way down, from rock to blues. One other piece of evidence in favor of Berry being the model is that while the Stones omit lyrics that appear in Berry’s interpretation, there are even more lyrics in McShann’s that Mick Jagger doesn’t sing. And Mick sticks much closer to the order of Berry’s lyrics than the order of McShann’s. The order’s exactly the same as Chuck’s version, in fact, though one of the verses Berry uses is axed. (It’s also possible the Stones were influenced by harmonica great Little Walter’s midtempo arrangement of the song, which he recorded for a single in January 1958.)

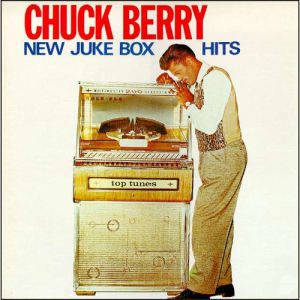

Along the same lines, there’s probably no one who doubts the Rolling Stones found “Down the Road Apiece” (on their 1965 LPs The Rolling Stones Now! in the US and The Rolling Stones No. 2 in the UK) through Chuck Berry. It was first done, however, in 1940 as a piano-based boogie by the Will Bradley Trio. Keith Richards copies Chuck Berry’s intro riff pretty much note-for-note, so there’s really no question the Stones took Berry’s interpretation as their model. Berry is also certainly the source for “Don’t Lie to Me,” first done as a piano-guitar blues with a kazoo solo in 1940 by Tampa Red, and redone on Berry’s 1961 album New Juke Box Hits, Fats Domino having done a cover in 1951 as well. The Stones recorded this in June 1964, but didn’t put it out until the 1975 outtake collection Metamorphosis, by which time the title had somehow changed from “Don’t You Lie to Me” to just “Don’t Lie to Me.”

The Rolling Stones learned, performed, and recorded quite a few songs from the above two Chuck Berry LPs.

New Juke Box Hits was also where the Rolling Stones learned “Route 66,” one of the most popular tracks on their 1964 debut album. Written by Bobby Troup, it was a big hit in a far more polite, jazzy version for Nat “King” Cole in 1946, back in the days when he led the King Cole Trio. But the weirdest intermediary version you could imagine helped the Stones learn the lyrics, though not the way they played it (which was taken from Berry’s version, as is obvious again from how the band does a more guitar-oriented variation of the opening piano-dominated riff of Chuck’s track).

For according to the memoir of Jimmy Phelge—the same “Phelge” who was honored by half of the Nanker-Phelge pseudonym used on early Rolling Stones group compositions—they learned the lyrics not from Berry’s version, but…Perry Como’s. Phelge shared a flat with Mick, Keith, and Brian Jones in 1963, and when he moved in, he brought with him a Perry Como LP. After the founder Stones were done laughing at him, they noticed that “Route 66” was on it. According to Phelge’s book Nankering with the Rolling Stones: The Untold Story of the Early Days, Jones then suggested to Jagger, “Why don’t you get the words down?”

Wrote Phelge, “Mick played it three more times until he had finished writing all the words down. When Mick had finished Keith leapt over to the record player. He hastily removed the Como album then said, ‘Thank Christ, let’s have some Chuck Berry.’”

From Robert Wilkins to Perry Como…you never thought we’d get there. Did you? But there’s one thing that links them together—recordings they did influenced cover versions done by the Rolling Stones, if in the most different ways imaginable.

The Perry Como version of “Route 66” from which Mick Jagger wrote down lyrics could well have been on this LP.