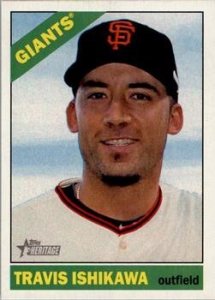

Travis Ishikawa, who won the last round of the National League playoffs for the San Francisco Giants last year with a game-ending home run, was designated for assignment by the club a few weeks ago. You can never count this guy out considering how often he’s been up and down (and not just with the Giants) for the last ten years, but he’s probably finished in San Francisco, especially since it’s the second time he’s been DFA’d this year. (He has subsequently hooked on with the Pittsburgh Pirates.)

I happened to be at the game in late June marking his first time at bat in the big leagues since last year’s postseason, and typical of how this year’s gone for him, he struck out. He’s never gotten much playing time since his first call-up in 2006, and there’s no place for a subpar outfielder on a club with two guys ahead of him at his real position, first base. Sure, he helped the team win the World Series last year, especially with his mighty playoff blow. But as the chairman said in that Monty Python sketch where an accountant is fired for embezzling a penny, “There’s no room for sentiment in big business.”

Ishikawa’s demotion did get me thinking about how many players in major league history with otherwise undistinguished careers are known just for one hit, or one game, or even one play. No doubt there are interesting instances absent from the list below, especially from baseball’s early years. Here, however, are a few of them, some by players who compiled much more impressive career records than Ishikawa, and some who were yet more marginal.

Howard Ehmke: It’s a pretty well known story in World Series lore: how a veteran pitcher, on the verge of getting released, got the first start of the 1929 World Series and excels, setting a record (since broken, but which stood for many years) by striking out 13 batters. His team, the Philadelphia A’s, went on to win that series, in part because of a miraculous comeback from an 8-0 deficit with a ten-run inning in one game.

Some colorful retellings have it that Ehmke convinced manager Connie Mack to start him, telling him he had one good game left in his arm, Mack sending him to scout the Chicago Cubs hitters in advance. Actually, however, Ehmke had pitched very well (if seldom) during the regular season, going 7-2 with a 3.29 ERA in a hitters’ era. He won a couple games in September, too, making it doubtful he was on the verge of getting let go. This article at seamheads.com has a lot of interesting detail exploding the myths around Mack’s decision to start Ehmke, which was likely a shrewd, if risky, hunch that his delivery would be tough on the Cubs’ hitters.

When this tale is told, the impression is sometimes given that it was Ehmke’s last game. That would make for a great story, but again, it wasn’t the case. He also started the last game of the series, and didn’t do nearly as well, getting removed in the fourth inning (perhaps the Cubs were on to his delivery by then), though the A’s won the game. He also pitched in three regular season games for the A’s in 1930, getting bombed to the tune of an 11.70 ERA before leaving the bigs for good.

Ehmke was actually a pretty good pitcher, with a career record of 166-166, sometimes for pretty bad teams. His other big claim to fame, though not nearly as celebrated as his 13 strikeouts, is nearly pitching two no-hitters in a row in 1923. In the no-hitter, a batter hit what seemed to be a double, but was called out for missing first base; in the one-hitter that followed, an apparent error was called a hit by the official scorer.

Floyd Giebell: When a close three-way race for the American League 1940 pennant came down to the final three games, the Detroit Tigers needed to win just one of the three they were playing against the Cleveland Indians (also in the race) to clinch. Pitching for the Indians in the first game was Bob Feller, one of the greatest pitchers of all time, and perhaps the best pitcher in the game at that particular time.

It was assumed the Tigers would pitch one of their front-line guys, like Bobo Newsom, Tommy Bridges, or Schoolboy Rowe, all among the better pitchers of the era. Instead they selected Floyd Giebell, a 30-year-old rookie whose major league experience consisted of 24 innings. As Tigers outfielder Barney McCosky remembers in Cobb Would Have Caught It (a fine oral history book of vintage Tigers stories), “We didn’t want to throw one of our best pitchers against Bob in the first game. So we had a meeting. We had Newhouser, Hutchinson, and a young guy called Floyd Giebell. We took a vote and we picked Giebell.” In Baseball When the Grass Was Real, Feller speculates the Tigers wanted to have all of their best pitchers available for the last two games, and were willing to concede the first, figuring it was unlikely to best Bob.

One of the finest relatively obscure baseball books is this oral history of the Detroit Tigers from 1920-1950.

And guess what? Giebell pitched a shutout, and the Tigers won, 2-0, clinching the pennant. Giebell had pitched a complete-game victory nine days before (when the team had to play doubleheaders on two consecutive days), in his only other appearance that year. But he’d joined the club too late to be ineligible to pitch in the World Series (which the Tigers lost), and after 34 innings with a 6.03 ERA and an 0-0 record the following year, he never played in another major league game. “We stopped down in Virginia once to see if he was still there,” said McCosky in Cobb Would Have Caught It. “We looked in the phone book, but no luck.”

As another odd footnote, during this memorable game, as Richard Bak wrote in Cobb Would Have Caught It, “Indian fans peppered their guests with obscenities and trash. [Catcher] Birdie Tebbetts, minding his own business in the bullpen, was knocked out when someone in the upper deck dropped a basket of empty beer bottles and garbage on him.”

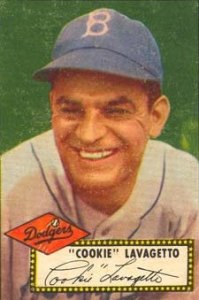

Bill Bevens: It’s a surprise to me that the fourth game of the 1947 World Series doesn’t show up more often on lists of the greatest baseball games ever played. The ending, at least, couldn’t have been more dramatic. For Yankees pitcher Bill Bevens was just one out away from a no-hitter, only to lose it – and the game – on the very last pitch, when Cookie Lavagetto doubled in two runs to win it for the Brooklyn Dodgers, 3-2.

The game’s often been written about, but here are a couple things sometimes forgotten about:

Bevens, who’d had a couple pretty good years for the Yankees in the mid-1940s, never pitched in the majors after 1947, when he wasn’t so great (with a 7-13 record). However, this loss wasn’t the last game he ever pitched in the big leagues. He redeemed himself with two and two-thirds innings of scoreless relief in game seven of the world series, which the Yankees won, though Bevens wasn’t the winning pitcher.

Lavagetto might not have ever gotten to the plate if it wasn’t for yet another hero-for-a-minute, reserve outfielder Al Gionfriddo, stealing second as a pinch runner in the bottom of the ninth. Gionfriddo is mostly known for robbing Joe DiMaggio with a big catch later in the series, but his steal set up the Yankees’ controversial intentional walk of a hobbling, injured Pete Reiser. That put the winning run on base, another pinch runner (Eddie Miksis) scoring that on Lavagetto’s double.

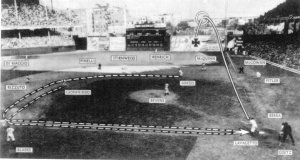

Great graphic showing the motion and positioning of players on the field when Cookie Lavagetto broke up Bill Bevens’s no-hitter with a game-winning double.

Part of the reason he was struggling to win a no-hitter in the first place was that he’d walked ten batters. Had Bevens finished the no-hitter, it would still be the record for most walks in a no-hitter in any major league game (or at least tied for the record, Jim Maloney walking ten batters in a 1965 no-hitter during the regular season).

I can’t find the source for this quote, but I remember watching a special on the 1947 World Series on public television as a young teenager back in the mid-1970s. If I remember correctly, as the story was told on the program, one of the announcers of the game apologized to Bevens the next day for jinxing the no-hitter by letting listeners know it was happening as it was in progress. Bevens told the announcer that the announcer hadn’t lost the game; the bases on balls had lost the game.

Al Gionfriddo: The 1947 World Series was quite the series for unlikely heroes (and goats). Gionfriddo is solely remembered for robbing Joe DiMaggio of an extra-base hit with a catch near the fence in the sixth game. The memory was ensured by a shot of DiMaggio, at a time when games such as these were just starting to be filmed and broadcast, kicking the dirt in anger in a rare display of public emotion. This was indeed Gionfriddo’s final major league game; he didn’t play in game seven, though as noted above he had a crucial role in winning game four.

Cookie Lavagetto: The guy who hit the double that broke up Bevens’s no-hitter actually had a fair major league career, with several seasons as the Dodgers’ regular third baseman (including 1941, when they also lost to the Yankees in the World Series). He was an infrequently used reserve in 1947, however. Like Bevens and Gionfriddo, he didn’t play in the majors after 1947. But although his double was his last big-league hit, it wasn’t his last big-league appearance, Lavagetto going hitless in four at-bats later in the series.

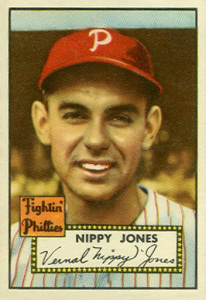

Nippy Jones: Skipping ahead ten years, in 1957 Nippy Jones was a seldom-used pinch-hitter/backup first basemen for the Milwaukee Braves. He’d seen some regular playing time for the Cardinals in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and batted .300 one year, but didn’t have enough power to stick with the big club. He didn’t even play in the majors from 1953 to 1956.

Game four of the 1957 World Series was an incredibly tense one that would be much better remembered if it was a game seven. Leading 4-1 against the Yankees with two out in the ninth, Hall of Famer Warren Spahn gave up a three-run homer to Elston Howard. The Yankees went ahead 5-4 in the top of the tenth, and Jones pinch-hit for Spahn to lead off the bottom half.

Tommy Byrne’s first pitch went by Yogi Berra, and Jones argued that it had hit him in the foot. He wouldn’t have won that argument if he hadn’t shown umpire Augie Donatelli a mark that his shoe polish had made on the ball. He took first base and left the game for a pinch runner—and he’d never appear in another major league game.

Which wouldn’t mean much, except the pinch runner scored, setting up a game-winning home run by Johnny Logan. Here’s something I didn’t know until reading the chapter on Tommy Byrne in the recent book Bridging Two Dynasties: The 1947 New York Yankees: “Byrne said that if Berra had thrown the ball back to him instead of holding onto it for Donatelli, Byrne would have marked it up so that nobody could spot the shoe polish.”

Incredibly enough, in the final game of the 1969 World Series, a very similar scenario played out with another player named Jones. The New York Mets’ Cleon Jones claimed a ball had hit him on the foot; manager Gil Hodges showed the shoe-polish mark on the ball to the umpire; Jones took first base; and a home run followed, starting their comeback from a 3-0 deficit to beat the Orioles. The game-tying home run the next inning was by light-hitting utility infielder Al Weis, who might also qualify for this list, although he had a pretty lengthy career and some other moments of note in that series (in which he hit .455).

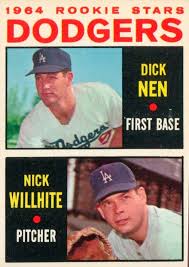

Dick Nen: Nen only had one hit as a Dodger, but it was a big one: a pinch-hit home run that helped win a crucial game in the 1963 pennant race. It was also his first hit in the major leagues.

Dick Nen got a 1964 rookie card after hitting a key home run for the Dodgers in 1963, but never played another game for the Dodgers in 1964 or any other year.

I’d wondered whether the importance of this hit had been blown up over the years, since the Dodgers did win the pennant by six games that year. At the time, however, it did seem that way. They went into a three-game series in St. Louis in mid-September leading by just a game. If Nen’s home run hadn’t tied the game in the ninth (the Dodgers went on to win 6-5 in 13 innings), they would have left St. Louis just two games ahead with nine to go.

Although Nen had some decent years in the minors, he never did play that regularly or well in the majors, where he spent a few years with the Washington Senators (and one with the Cubs). Ken Harrelson’s memoir Hawk tells of how Nen was embarrassed to be getting the opening day start in 1967 ahead of Hawk, who wasn’t getting along well with Senators manager Gil Hodges. To Giants fans, Dick Nen’s most known for being the father of Robb Nen, their relief ace from 1998-2002.

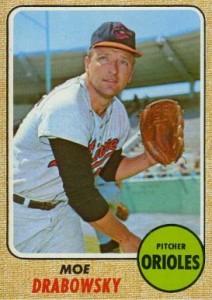

Moe Drabowsky: After faring rather poorly as a starter for his first few years, Drabowsky had a pretty good career as a reliever for the final half or so of his time in the big leagues, though he was never an ace. His best years were for the Orioles in the late 1960s, and though he was lost to the Royals in the expansion draft, he came back to Baltimore during the 1970 season to contribute to their world championship that year.

His contribution to their 1966 World Series win, however, was far greater and more memorable. In the first game of the series, he relieved a struggling Dave McNally and struck out 11 batters (including six straight at one point) in 6 2/3 innings, giving up just one hit. That would be an excellent start, and as a relief appearance, it’s easily the most impressive in World Series history. All 11 strikeout victims went down swinging.

Other than for this game, Drabowsky is most notable as one of baseball’s most notorious practical jokers. Some of these (like giving the hotfoot or scaring teammates with snakes) aren’t all that interesting to read about. But his best one—impersonating (while he was with the visiting Orioles) Kansas City A’s’ manager Alvin Dark on calls to the A’s bullpen, getting A’s pitcher Lew Krausse to needlessly warm up—is classic.

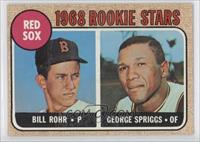

Billy Rohr and Gary Waslewski: The Boston Red Sox’ “impossible dream” pennant victory of 1967 has lots of interesting stories, two of which belong to some of their least successful players. On April 13, rookie Billy Rohr almost got a no-hitter in his very first major league game, the Yankees’ Elston Howard breaking it up with a single with two out in the bottom of the ninth. One pitcher in the modern (post-1900) era has thrown a no-hitter in his first big-league start (Bobo Holloman in 1953), but to this day, no one has done so in his first game. But that was his main contribution to the team that season. He began the year as the Red Sox’ third starter, but pitched poorly after that sensational debut, getting sent down to the minors a couple months later after just one more victory, and winning only three games total in his major league career.

Although Bill Rohr got a 1968 Red Sox rookie card (still being a few innings short of losing his rookie status), he didn’t pitch for the Red Sox in 1968 or any year after that, though he appeared in some games for the Indians in 1968.

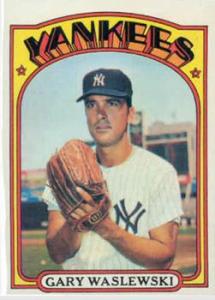

Rohr didn’t pitch for the Red Sox in the World Series, but a barely more experienced hurler ending up starting a crucial game. Gary Waslewski was a seldom-used rookie on the team that year, compiling a 2-2 record in twelve games, eight stars, and 42 innings. He was only eligible for the series because another pitcher, Darrell Brandon, had to be replaced due to an injury. He hadn’t started since July 29. But on October 11, with the Sox facing elimination down three games to two against the Cardinals, Waslewski, who’d pitched well in relief in a loss in game three, got the ball to start. He didn’t do great, but he did well enough, getting into the sixth and keeping the Red Sox in the game, which they won 8-4 (though Gary didn’t get the victory, and the Sox lost the series in game seven).

Waslewski bounced between a few teams over the next five years, never pitching more than 130 innings in a year, and ending his career with a 12-26 record. Is that the least impressive career won-loss record for any World Series starter?

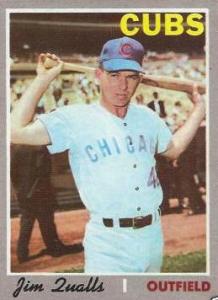

Jim Qualls: On July 9, 1969, in the midst of the Miracle Mets’ run toward the World Series, ace Tom Seaver brought a perfect game into the ninth inning against the team they were chasing for the Eastern Division lead, the Cubs. With one out, a little-known rookie reserve outfielder named Jim Qualls stroked a clean single to left field. It remains his only claim to modest fame, Qualls finishing the year with a fairly poor .608 OPS in just 124 plate appearances. He did play a bit for the Expos and White Sox in 1970 and 1972, but with even less distinction, going 1-19 post-1969, and ending his career without a home run.

“When I got to first base, I was never booed so bad in my life,” said Qualls in this article on him for the SABR Baseball Biography Project. “We got back to Chicago and I got all this hate mail. You could tell by the handwriting it was just kids, little Mets fans: ‘You bum, don’t show up in New York.’ I don’t get any letters like that anymore.” The only subsequent meeting between Qualls and Seaver came less than a week later when they crossed paths while running in the outfield, Seaver telling Qualls, “You little (bum), you cost me a million dollars!”

Seldom remembered, incidentally, is that the batter before Qualls, Randy Hundley, had tried to bunt for a base hit, though the Cubs were down 4-0. Bunting for a base hit to break up a no-hitter is still considered violating an unwritten law, and would have probably sparked enormous controversy had Hundley beaten it out. The Mets got their revenge in early September when one of their runners was called safe at the plate in a key close game against the Cubs, despite Hundley’s furious protests.

The darkness to Qualls’s light, perhaps, was supplied the previous day by another Cubs rookie outfielder, Don Young. Young remains known almost solely for misplaying a couple flyballs in the ninth inning of a game against the Mets on July 8, helping lead to a come-from-behind 4-3 victory for New York. The misplays also stirred up controversy in the Cubs clubhouse after the game when All-Star third baseman Ron Santo and manager Leo Durocher harshly criticized Young to the press (Santo subsequently apologized to Young in prive and public), though the Cubs’ true collapse didn’t start until about a month and a half later.

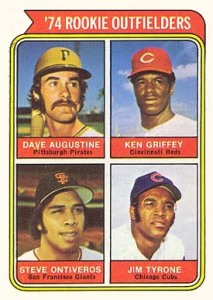

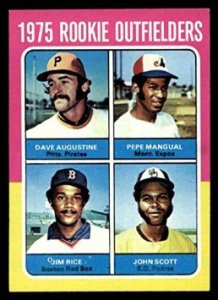

Dave Augustine: In one of the weirdest key pennant-race games of all time, Pirates rookie reserve outfielder Dave Augustine appeared to have put Pittsburgh ahead of the New York Mets on September 20, 1973 with a home run in the top of the thirteenth. The ball landed at the very top of the fence, but took a freak bounce back to outfielder Cleon Jones, and via a relay from third baseman Wayne Garrett, Pirates runner Richie Zisk was thrown out at the plate. The Mets went on to win in the bottom of the inning, and win, narrowly, the Eastern Division, going on to win the pennant before losing the World Series in seven to the A’s. This was a big game, bigger than the one Dick Nen won in 1963; had they lost, the Mets (who won the division by a game and a half) would have been two and a half games out of first with eight to go, instead of just a half game back.

In the cruelest footnote, not only was Augustine denied his Dick Nen moment. Having come as close as possible to a home run (in one of only seven at-bats he had in 1973) without getting it, he never did hit a home run in his big-league career, which lasted just 29 games and 29 at-bats.

After his 1973 near-homer, Dave Augustine got rookie cards in both 1974 and 1975, but didn’t come close to getting enough at-bats to lose his rookie status.

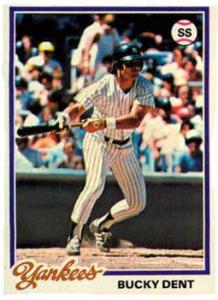

Bucky Dent: Probably the most famous instance of a player-known-for-just-one-thing—even more so than Bill Bevens—is light-hitting Yankees shortstop Bucky Dent, whose three-run homer keyed their dramatic 5-4 one-game playoff win over the Red Sox to win the 1978 Eastern Division. Dent actually had a respectable twelve-year career, though he was known more for his defense than his offense, hitting .247 lifetime with just 40 home runs (and only five in 1978). Volumes have been written about that game, and season, some participants and observers (especially Red Sox fans) viewing it as a cheap homer over Fenway Park’s notoriously short-distance left-field wall. But hey—the Red Sox also had chances to hit homers there that game.

It’s sometimes forgotten that Dent had an excellent World Series that year, hitting .417, driving in seven runs, and winning the series MVP award. The even unlikelier hero of that series, however, was…

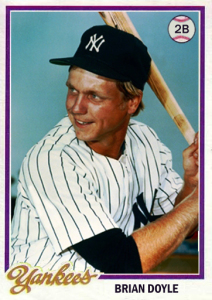

Brian Doyle: Rookie Brian Doyle had an undistinguished year for the Yankees in 1978, hitting .192 in 52 at-bats with no extra-base hits or walks. Regular Yankees second baseman Willie Randolph got injured before the post-season, however, and Doyle got most of the playing time at the position in the World Series. And he delivered, going 7-for-16 with, most dramatically, four hits in the series-winning victory in game six, including a double—his first extra-base hit in the majors.

Doyle did play for three more years in the majors, but not well, ending up with a .161 average in 199 at bats, and just four extra-base hits (though one of them was a home run). He is, incidentally, the younger brother of Denny Doyle—who, though he had a better and much lengthier career as a second baseman, is also most famous for a World Series game, though in a negative way. Denny Doyle’s error on a potential inning-ending double-play ball in the seventh game of the 1975 World Series set up a two-run homer by Tony Perez, in a game the Red Sox lost by one run.

Mark Brouhard: One of the least familiar names on this round-up, reserve outfielder/DH Brouhard is perhaps the greatest one-game wonder in postseason history. In game four of the 1982 American League playoffs, he hit two doubles and a home run, leading the Brewers to victory over the Angels in a five-game series they won after being down 2-0. Playing in place of injured outfielder Ben Oglivie, Brouhard somehow never got in another game either that series or in the World Series, which the Brewers lost in seven games.

Brouhard did have a six-year career as a part-timer, and not such a great one, with a .705 OPS and 25 home runs. “It was frustrating at the time,” Brouhard told the Los Angeles Times in 1991 of his failure to appear in the World Series. “I felt that I deserved a chance to play some in the World Series. I felt like I had earned it.

But (manager Harvey Kuenn) felt that this might be the veterans’ one shot to play in the World Series and he went with them…As it turned out, we lost anyway.”

Tom Lawless: For a player with such an unremarkable career as a multi-position reserve, Lawless has had some remarkable highlights. One, if you can call it a highlight, was being traded for Pete Rose late in the 1984 season, near the end of Rose’s time as a player. Another was hitting a home run in the 1985 World Series, after a season in which he’d gone 2-25 for an .080 batting average. It was his only hit in ten at-bats that series, which his Cardinals lost in seven games to the Twins. He wasn’t much better over the course of his playing days, chalking up a measly .521 OPS and two homers in eight years, during which he accumulated just 590 plate appearances.

On the brighter side, he was 53-66 lifetime as a base stealer; in fact, between 1986 and 1989, he was a rather splendid 28-30. He also managed the Houston Astros for 24 games last September, though it was just an interim position for the luckless Lawless.

Billy Bates: Bates had the least distinguished career of any player on this list. He appeared in 25 games as a pinch-runner and second-baseman, hitting .125 with one extra-base hit (a double) in 48 at-bats. But the Reds picked him up for some roster depth at the end of 1990, which made him eligible for the World Series that year. In game two he delivered his only hit in a Cincinnati Reds uniform (he’d gone 0-5 for them in the regular season) by beating out an infield single as a pinch-hitter, scoring the game-winning run in a series the Reds swept from the A’s.

A la Nippy Jones, Bates never played in a major-league game after scoring this run (though he at least got to stay in the game after reaching base). Another strange footnote: it was his only hit against a right-handed pitcher in his career, coming against Hall of Famer Dennis Eckersley, no less.

Gene Larkin: The seven-game 1991 World Series between the Braves and the Twins is pretty well-remembered. So is Gene Larkin, though even some fans who watched the series forget that he’s the guy who delivered the single that won the game for the Twins in the bottom of the tenth inning of the seventh game.

Larkin had a pretty nondescript career as a multi-positional player for the Twins from 1987-1993. He never quite established himself as a regular, had a .723 OPS, and only made twelve plate appearances in the 1987 and 1991 postseasons. His game-winning hit, over a drawn-in outfield, would in most situations have been an average flyball (if deep enough to score runners from third). But, more than almost any player in baseball history, he was in the right place at the right time.

“I was a role player,” he acknowledged to Baseball Digest in 2002. “An average player at best. If I didn’t get this hit, I’d be just another player who had a so-so career.” But as the article reported, “It doesn’t matter here he goes or what he’s doing…shopping, eating, playing golf, or just going for a walk. People are always shaking his hand or patting him on the back. ‘Every time I play golf, it happens. Just a few days ago, a gentleman I didn’t know said, “Thanks a lot for ’91.” People want to thank me, congratulate me or tell me how happy that hit makes them feel.’”

Francisco Cabrera: A reserve catcher and first baseman for the Atlanta Braves in the early 1990s, Cabrera had just 374 at-bats over the course of a five-year career. He wasn’t that bad, hitting 17 home runs in that span, and posting an okay .747 OPS. He was never good enough, however, to get regular playing time, and had just ten at-bats in the Braves’ 1992 pennant-winning season.

He still got on their playoff roster, and was the pinch-hitter chosen when the Braves were one out from elimination against the Pittsburgh Pirates. With his team down 2-1 and two out in the bottom of the ninth, he hit a two-run single that won the pennant for Atlanta and sent the Pirates home.

There’s some speculation, incidentally, that had a superstar on the other team been playing the game more astutely, the outcome could have been very different. Wrote Mark Fainaru-Wada and Lance Williams in Game of Shadows, when Cabrera came to the plate, “Andy Van Slyke, the Pirates’ centerfielder, whistled to Bonds, then signalled with his glove for him to move in and to his left. Bonds looked at Van Slyke, but didn’t move. Instead, he stayed just where he was, deep, guarding the left-field line. Until he won his first MVP in 1990, Bonds had been paid less than Van Slyke, and he still resented it. Bonds called him ‘the Great White Hope.’

“Cabrera slapped a base hit to left field, about where Van Slyke had tried to get Bonds to play. The runner on third, David Justice, trotted home with the tying run. On second for the Braves was the slow-footed Sid Bream, a former Pirate who once said that everybody in the Pittsburgh clubhouse had wanted to punch Barry out at one time or another. As Bonds played the ball, Bream rounded third and lumbered home. Bonds’s throw was strong, but it was up the first base line. Bream scored, and the Braves were in the World Series.”

Chad Curtis: An unhappier ending was in store for Chad Curtis, an outfielder with a ten-year career that was better than Larkin’s, but not much. He did manage to clear 100 homers and 1000 hits, with a .745 OPS. And though his 1999 season wasn’t that special (five homers and a .767 OPS in 245 plate appearances), in game three of the World Series he hit two home runs for the Yankees, the second winning the game in walk-off fashion.

Right after the game, Curtis was interviewed on national TV by sportscaster Jim Gray. Well, not quite interviewed: Curtis told Gray, on-camera, that he wouldn’t speak to him because of a critical interview Gray had done with Pete Rose before game two. At that moment, it was hard to decide who was more unlikable, Curtis or the characteristically irritating Gray.

While his refusal to be interviewed had no negative consequences on his reputation as far as I can tell, an off-field incident many years later did. On October 3, 2013, Curtis was sentenced to seven to fifteen years in prison for six counts of criminal sexual misconduct, stemming from accusations of sexual harassment from several female students at the high school where he was coaching.

Geoff Blum: The 2005 World Series is disdained by those who want higher-profile matchups than the Astros vs. the White Sox, or seven-game series, not four-game sweeps. Actually, however, this series was about as exciting as four-game sweeps got, with close games and quite a bit of drama and strategy. The crucial blow in the most exciting game was a two-out homer in the top of the 14th inning by Geoff Blum, an infielder (for the most part) for 14 years, and several teams, without ever quite gaining a regular job. He had a lifetime .694 OPS and 99 home runs – 100, however, if you add that World Series shot.

Blum only had 99 plate appearances for the White Sox that year (and just one home run in the regular season for the team), and would never play for the Sox again. What’s even more notable about his home run than its timing, however, is that it was his only World Series appearance, for the White Sox or anyone else. He is, incidentally, not the only player to hit a homer in his only World Series at-bat, the other being the yet more obscure infielder Jim Mason, who hit his for the Yankees in the third game of the 1976 World Series. The Yankees were swept in that series, and Mason was one of the worst players in this roundup, with a lifetime OPS of .534 and 12 home runs in nine years of mostly part-time service.

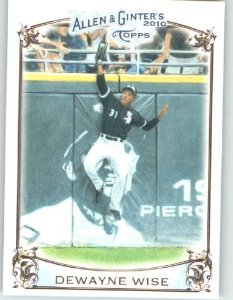

DeWayne Wise: Most of the players on this list performed their heroics or near-heroics in the post-season or the heat of the pennant race. Here’s an instance, however, of a spurt of brilliance that happened in a regular season game, and not a particularly meaningful one. On July 23, 2009, Mark Buehrle’s perfect game was saved in the ninth inning by reserve outfield DeWayne Wise, who was in as a defensive replacement and robbed the Tampa Bay Rays’ Gabe Kapler of a home run. To quote Wikipedia, “To thank Wise for his play Mark Buehrle gave him a bottle of Crown Royal XR in a cloth bag embroidered with his name and the date of the perfect game.”

On the strength of his defense and base-running, Wise scratched out an eleven-year career despite a subpar .645 OPS. Another perfect-game saving play was made a few years ago by Giants outfielder Gregor Blanco, who made a spectacular diving catch in the seventh inning to preserve Matt Cain’s June 13, 2012 gem. That’s probably what Blanco will be most remembered for, though he’s building a career as a modestly useful Giants reserve outfielder.

Yusmeiro Petit: As long as we’re talking Giants, the last name on this list is a teammate of Blanco’s and, for that matter, Travis Ishikawa (or at least he was a teammate of Ishikawa before this month). Yusmeiro Petit, on the Giants’ staff as I write this, has had a journeyman career, with a lifetime ERA of 4.72 and a win-loss record of 20-27. He’s had his moments with the Giants, however, losing a perfect game on September 6, 2013 with a 3-2 count and two out in the ninth inning. The following year, he set a major league record by retiring 46 batters in a row (over the course of eight appearances). More memorably, he pitched six scoreless innings out of the bullpen to get the win in an 18-inning playoff game against the Nationals in 2014, with seven strikeouts and just one hit allowed—not as impressive a performance as Moe Drabowsky’s, but still an amazing one, given the circumstances.

In this post, I haven’t cited the numerous players who are known primarily for an on-field failure. And there are many: Mickey Owen’s dropped third strike in the 1941 World Series, Fred Merkle’s failure to touch second base on a (nearly) game-ending single in a key game in the 1908 pennant race, Donnie Moore giving up Dave Henderson’s home run to erase what seemed a certain victory in the 1986 playoffs, etc. Maybe those will be a subject for a future post. Because the infinite possibilities of how baseball games play out will certainly leave room for more remembered-only-for-this feats in the future, good and bad.