Dave Dexter is not the most popular figure in Beatles lore. He’s most notorious for adding reverb to some of their early recordings for their US releases on Capitol Records—mixes that can be heard on the CDs The Capitol Albums, Vol. 1 and The Capitol Albums, Vol. 2. He’s also infamous for rejecting the Beatles’ first four singles for American release, before Capitol finally issued “I Want to Hold Your Hand” at the end of 1963 to launch Beatlemania in the US.

Remembering the first time he heard the Beatles in a 1988 interview with Chuck Haddix, Dexter groused, “When I heard Lennon playing the harmonica on this record, I thought it was the worst thing I’d ever heard. So I nixed it. I didn’t want any part of the Beatles.” (Probably the record was “Love Me Do,” though Dexter could not remember the title in this conversation.) In a mid-1980s interview for the radio documentary From Britain With Love, he elaborated, “I didn’t care for it at all because of the harmonica sound. I didn’t care for the harmonica because I had grown up listening to the old blues records and blues harmonica players, and I simply didn’t…I nixed the record instantly.”

As Mark Lewisohn wrote in the extended edition of The Beatles Tune In:

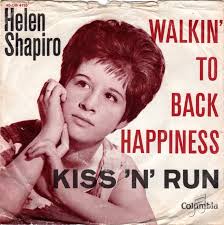

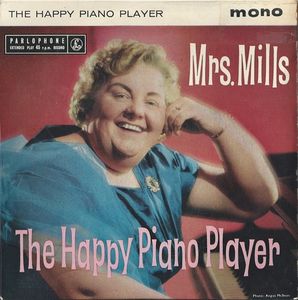

“The fact Vee Jay was having a huge hit with a harmonica record Dex had nixed a couple of months earlier [Frank Ifield’s “I Remember You”] prompted no circumspection, and neither did the success Capitol was having with another self-contained vocal-instrumental group, the Beach Boys. Dexter had no love for the British and a neat way of showing it. Though he rejected the Beatles, the Shadows, Cliff Richard, Adam Faith, Helen Shapiro and Matt Monro, he did issue ‘Bobbikins,’ a piano instrumental by Mrs. Mills. Gladys Mills was that most British of discoveries, an ample, 43-year-old, heavy-wattled housewife who chopped out party singalong numbers on a saloon-bar-like piano. After finding sudden TV fame late in 1961, she was signed to Parlophone by Norman Newell, but while her debut single was a hit, the follow-ups weren’t—and it was one of these failures that Dex decided America needed.”

Mrs. Mills, one of the British artists who was issued on Capitol Records at a time when the Beatles’ early British hits were being rejected by the label for American release.

Not much has been written about Dexter and the Beatles (though it’s likely Lewisohn will have more to say about the matter in the next volume of his mammoth Beatles biography, Tune In only covering their history through the end of 1962). While researching something else, I stumbled across a section of the website of the University of Missouri-Kansas City’s library that features some little-known memos from Dexter’s time at Capitol. These don’t exactly exonerate the executive’s handling of the Beatles, but do offer a more fully rounded picture of how he dealt with British product at the time the British Invasion was gaining steam.

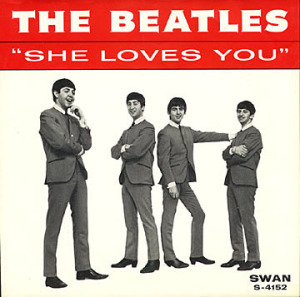

There probably wasn’t much if any internal discussion about Dexter’s rejection of the early Beatles discs, or other early British rock records, before 1964. The Beatles’ second, third, and fourth UK singles—all British chart-toppers, with “She Loves You” becoming one of the biggest sellers ever in that country—were issued in the US by either Vee Jay or Swan after Capitol passed, and sold little. Very few British rock records of any kind had been hits on the US charts.

That changed instantly with “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” which was a massive American hit as soon as it was issued by Capitol on December 26, 1963. In his interview with Chuck Haddix (available as a sound file on the University of Missouri-Kansas City site), interestingly, Dexter remembers being played the song in September or October (he gives the year as 1962, an obvious mistake) by an A& R man on a visit to England. Probably knowing Dexter’s resistance to the Beatles, the A&R guy (Tony Palmer) played him the track without telling him who it was. “Boy, I heard about four bars of that and grabbed it,” he says, though A) it didn’t take golden ears to tell it had enormous sales potential, and B) other sources, to my knowledge, have never pinpointed Dexter as the guy who made the decision to release this in the US, or lobbied for its release there by Capitol.

Dexter does not improve his credibility by remembering the incident somewhat differently in his obscure 1976 autobiography Playback. There he remembers Palmer telling him the single was a Beatles record before playing it. That’s a minor detail, but Dexter also writes that he told Palmer, “Capitol will take full page ads in the three major trade papers, and we will send special pressings and biog sheets to all the important radio stations. We’ll go all out.” According to the Los Angeles Times obituary for Alan Livingston, however, the key impetus behind “I Want to Hold Your Hand” gaining Capitol’s support was a personal call to Livingston from Brian Epstein. The issue of who exactly was the big cheese behind deciding Capitol would not only release “I Want to Hold Your Hand” but promote it heavily remains unclear, to the point of wondering whether several people at the label scrambled to take credit after Beatlemania took off in the US.

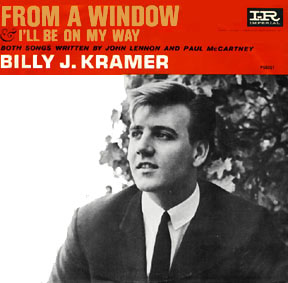

A February 20, 1964 memo from Dexter to Alan Livingston (the guy usually credited with approving “I Want to Hold Your Hand” for US release) indicates the heat was on for Dave to both examine British rock product more carefully, and justify why he’d passed on acts other than the Beatles who were now beginning to make American waves. “Billy Kramer and the Dakotas and Gerry and the Pacemakers were offered to Capitol nearly a year ago along with numerous other rock combos, solo singers, vocal groups, orchestras, comedy acts and other EMI artists,” Dexter writes. “I waived on both of them because neither had a particularly unique sound. Subsequently, they became big hits in England but the American labels who put them out here sold nothing.” Both groups would, of course, have big US hits over the next couple of years as the British Invasion became huge and labels issued or reissued their UK hits from 1963, some of which (like the Beatles’ 1963 singles) became belated American chart singles.

One wonders whether Dexter even knew that both Kramer and the Pacemakers were managed by Brian Epstein. Or that Kramer’s early hits were written by John Lennon and Paul McCartney—the same duo, it’s barely worth repeating, who penned the Beatles records that were now selling in enormous quantities for Capitol. Both factors in themselves would have made them worth adding to Capitol’s roster, both to ingratiate the label with Epstein and to get some hits with (admittedly secondary) additional Lennon-McCartney songs. If Dexter knew all this by February 20, maybe he was playing dumb in case that knowledge got him in even deeper hot water.

Had Capitol not rejected Billy J. Kramer’s early hits, it would have been able to issue otherwise unavailable Lennon-McCartney songs like these in the US.

Interestingly, in the next paragraph Dexter offers: “Freddie & the Dreamers, in my opinion, have a most attractive rock sound and might make it big over here, although the first record we issued sold hardly any copies. Freddie’s second record comes out next week on Capitol.” The Dreamers would indeed have a couple hits for Capitol’s Tower subsidiary—though not until early-to-mid-1965, and then with singles (“I’m Telling You Now” and “You Were Made for Me”) that had already been big British hits in mid-to-late 1963. Was Dexter trying to cover his tracks by snapping up another early British Invasion band while there was still time?

In the next paragraph, Dexter is more dismissive about the prospects of the Swinging Blue Jeans (who’d have some moderate US success in 1964) and the Fourmost (an Epstein-managed act, again with some Lennon-McCartney castoffs that had been British hits, that never charted in the US). “In my opinion, Capitol can handle only a small percentage of these groups,” he states. And Capitol would not put out records by the Swinging Blue Jeans, though it put out a few (including a cover of the Beatles’ “Here, There, and Everywhere”) a few years later by the Fourmost.

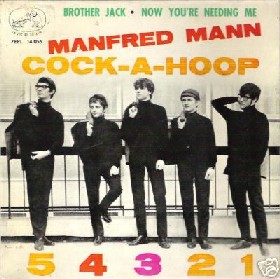

In the following paragraph, his judgments get more interesting. He reveals that he has passed on Manfred Mann’s first record. Remember, this is more than six months before they’d have their first US hit (the #1 single “Do Wah Diddy Diddy”), though they’d just landed their first big British hit that month with “5-4-3-2-1.” “Because the record sounded like something that had been made by Chess in 1951, I promptly cabled Tony Palmer to go ahead and place it elsewhere,” Dexter writes.

It would be useful to know if the “first record” he heard by Manfred Mann was indeed their first UK single (“Why Should We Not”/ “Brother Jack,” which were rather tame blues-jazzy instrumentals) or their second single (“Cock-a-Hoop,” an R&B number with Paul Jones on vocals). If it was “Why Should We Not”/“Brother Jack,” Dexter’s judgment actually seems sound, and his comparison of it as “something that had been made by Chess in 1951” fairly if not quite dead-on accurate. If it was one of the Jones vocal numbers, his assessment was a misfire, especially if “5-4-3-2-1” was already proving its worth by climbing the British charts. Manfred Mann’s US rights would get snapped up by a branch of United Artists, Ascot.

In the final part of the memo, Dexter further justifies his positions: “Alan, I make errors in judgment as does everyone else, but when you consider the enormous amount of singles and albums sent to my desk every month from not only English Parlophone, Columbia and HMV, but France, Germany Italy, Japan, Austria, Australia, the Scandinavian countries and several other places, I am frankly amazed that we do not miss out on more hits as the months and years go by.” He also notes, “Last week in England, there was quite a hypo in the trade on a new type of music with Jamaican influences called ‘the Blue Beat.’ I have already cabled for two sides and hope to be the first in North America to issue this new music, which is a sort of hybrid combination of rock with calypso.”

That’s a fairly accurate, if imperfect, capsule description of Blue Beat, better known as ska. Like his reference to Chess Records in 1951, this indicates that Dexter wasn’t wholly unhip, and did have some knowledge of trends and styles in the rock and pop world. But the one sort-of-bluebeat single to become a big hit in the US, Millie Small’s “My Boy Lollipop,” would be on Fontana, not Capitol.

As 1964 went on, scattered memos indicate Capitol was taking a closer look at the procedure by which British recordings were accepted or rejected, also taking steps to get other people involved besides Dexter. On September 21, Livingston wrote Dexter, “I would like a review of current activity, in particular our success of Cila [sic] Black and Peter and Gordon, and any recent misses that we may have had. I am thinking specifically of the Animals and if I understand the situation correctly, we turned down a master which was subsequently unsuccessful. As a result of turning down this master, however, under our agreement we lost future rights to the artist and therefore did not have a chance to take the successful Animals record now on the charts [“House of the Rising Sun,” then at #1]. I would like your confirmation or any further explanation of this.”

In response, Dexter sent a quite detailed report on October 1 noting (with sales figures) how poorly most British singles issued by Capitol had done in the American market (especially before 1964), even when they were hits in the UK or by big British stars like Cliff Richard and Johnny Kidd. In a quite frank sentence, Dexter explains: “By paying a few pennies bonus to every record shop sales girl in thousands of stores throughout the 50 states, Capitol pushed [Helen Shapiro’s] third single up to nearly 19,000 but it was a phony ‘hype’ and as Epic proved a couple years later, the girl simply did not have the sound for success in the American market.”

At one point Dave makes a quite interesting claim: “Today it is obvious that Capitol never would have reacquired the Beatles had I not been in London last August, nor would Capitol have gotten Frank Ifield, who although dormant today, sold a lot of singles and albums for us in a brief period of time.” This is not the usual way the story of Capitol’s decision to issue Beatles product has been portrayed. If Dexter was in London in August 1963, he wouldn’t have been able to hear “I Want to Hold Your Hand”—the song he remembered in his interview with Chuck Haddix as grabbing his attention—which hadn’t been recorded yet. Maybe he’s simply misremembering the month (albeit only a year after his visit), but he also fails to mention that although Frank Ifield did have low-charting singles for Capitol in late 1963, the label had missed out on his big US hit, “I Remember You,” which had gone to Vee Jay in 1962.

A little farther down, there’s more info that indicates that Dexter either didn’t remember exactly when he’d been in England, or that his role in the Beatles hooking up with Capitol is greater than is usually acknowledged. “In the summer of 1963, Vee Jay went bankrupt and Swan acquired the rights to the third American Beatles single [“She Loves You”]. Apparently, it sold fewer than 1,000 copies and Swan had no further interest in the group. By the time I returned from England in August of 1963, it was apparent that the Beatles were the hottest thing England had ever encountered and when I learned that Swan had waived on the group, I then somewhat hysterically started urging Livingston, [Capitol producer Voyle] Gilmore and Dunn to exert every possible pressure on EMI and Epstein. Mainly, promises of a promotional campaign,” he asserts.

There are a few odd aspects to this passage. Dexter writes this to give the impression that Swan had sold fewer than 1,000 copies of “She Loves You” and waived on the group around the time he returned from England in August of 1963 – though “She Loves You” wasn’t issued by Swan until September 16, 1963 (and not even by Parlophone in the UK until August 23). Just about every account I’ve come across has it that EMI and Epstein were pushing Capitol to release and promote Beatles records (and “I Want to Hold Your Hand” specifically), not the other way around.

Dexter goes on to admit he goofed by passing on Herman’s Hermits “I’m Into Something Good”; says he has “high hopes” for the Cherokees and “the committee feels that the Cresters and Shirley & Johnny have strong possibilities” (none of these acts would make the US charts); and though he liked the Zephyrs, “their artist royalty was more than Capitol cares to pay.” As for the Animals, he writes, incorrectly, that “House of the Rising Sun” was their third UK 45 (it was their second), adding that “House of the Rising Sun” was never submitted to Capitol “because we have waived on the group on March 27, 1964.”

He also claims that the Animals single they rejected, their debut disc “Baby Let Me Take You Home,” “did not sell any place in the world.” This was not true. It made #21 in the UK, a quite respectable showing for a debut at one of the most competitive junctures in British rock history. It seems like Dexter was trying to cover his Animals tracks here.

Then on to Manfred Mann, Dexter confirming that he rejected both of their first two singles, “Brother Jack” and “Cock-a-Hoop” (though it’s still not clear which of these reminded him of a 1951 Chess Records disc). Their third 45, “5-4-3-2-1,” was offered to him too, but he writes that it was already placed elsewhere by the time he was sent a sample. “The record was not very big in the U.S.A. but his succeeding records have been extremely successful,” he understates—at the time of the memo, “Do Wah Diddy Diddy” was making a beeline for #1 in America.

As for Gerry & the Pacemakers: “I have no excuses here. I did not think the sound of the group was extraordinary and I still believe that out of the hundreds and hundreds of samples submitted featuring various combos, that Gerry is nothing special. I missed!” On the Swinging Blue Jeans: “I missed on this group. They sounded like 983 other combos and they have enjoyed fair if not memorable success on a competitive American label.” For Billy J. Kramer and the Dave Clark Five, however, “I refuse to be the goat,” Dexter feeling he was pressured into making immediate decisions by Transglobal (a company licensing product to US labels) before he could give their product a fair hearing.

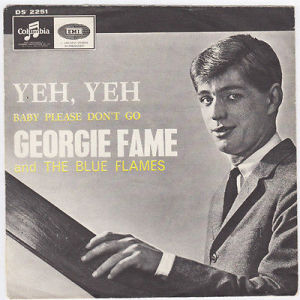

More justification follows in the form of a paragraph noting many flop acts Dexter passed on. And indeed, even today many British Invasion experts would be hard-pressed to recognize most of the names, though Georgie Fame would have a couple big US hits (and more in his native UK); Chris Farlowe had a British #1 in 1966 with the Rolling Stones’ “Out of Time”; R&B primitives the Downliners Sect have a cult following; and Sounds Incorporated got to tour with the Beatles. A longer list at the end of the memo includes a few other cool names who’d eventually have hits somewhere (but not the US) and/or have their own cult followings: Duffy Power, the Paramounts (who evolved into Procol Harum), ska star Laurel Aitken, and Julie Driscoll.

Dexter passed on Georgie Fame, leaving the path clear for Imperial to have a US hit with Fame’s UK chart-topper “Yeh Yeh.”

Dave also gripes about Capitol’s under-promotion of foreign acts in general: “Our exploitation of Cliff Richard was nil, although he was selling as many records during the Presley hysteria as Presley himself everywhere but the U.S.A. I am convinced we could have made Freddie and the Dreamers bigger than the Animals, Manfred Mann or Dave Clark, but we spent not a penny in his behalf.” (This was before Freddie & the Dreamers’ belated Stateside breakthrough in early 1965 with “I’m Telling You Now.”)

Freddie & the Dreamers would not become bigger than the Dave Clark Five, Animals, or Manfred Mann, though Capitol did issue a couple of their hits.

It must have been a strange, unsettling time for Dexter. Capitol, largely on the backs of the Beatles, was more prosperous than it could have possibly imagined in late 1963, especially considering it also had the Beach Boys and some other hit acts. At the same time, the label must have been beating itself up for allowing the first year or so of Beatles product to go to other US labels (though they’d get the rights to those early tracks by early 1965), and also for allowing other British Invasion acts on EMI UK to go to other American companies.

Dexter might have made an easy fall guy for this, though ultimately his judgment, to be charitable, was far from flawless. Out of the blue, seemingly, he was being inundated with music that no one in the US was paying any attention to before 1964. He was also getting called to account for the many decisions he had made and had to make about a style with which he was (again, like everyone else in the US) probably virtually wholly unfamiliar. As Dave wrote in the last sentence of his October 1, 1964 report: “The record business is a hell of a lot different than it was even a short year ago.”

Sadly, the link to memos dated April 8-June 14, 1965 titled “Turning Down Herman’s Hermits & Livingston’s Push That Capitol ‘Should Not Be Asked To Give Up An Artist Until They Have Had A Success Or Failure In England’” gets a “page not found” message on the University of Missouri-Kansas City Libraries site. A final brief memo from Alan Livingston to Dexter from August 31, 1965 indicates the Beatles wanted to exert more control over their Capitol releases, reading: “”In a meeting with Brian Epstein yesterday, he expressed the very strong hope that we would consider using the same art work for our Beatle album covers as England uses. Please let me know if this is possible, and if so, what the complications, if any, might be.”

By this time, Dexter might have had his fill of the Beatles, and not just because he was pretty much being called on the carpet for his decisions about them and other British Invaders. The bad feelings lingered for a long time. In a Billboard story about a couple weeks after John Lennon’s death, he wrote that Lennon and McCartney had called him from Miami on their first US visit “to praise the ‘fabulous’ sound Capitol’s engineers had achieved on American releases,” but that John subsequently “advised Capitol’s management that he didn’t care for the album covers Capitol was devising. Lennon didn’t like the back covers, either. Nor did he approve the sounds of the Beatles tapes issued by Capitol, an abrupt 180-degree turnaround from his previous praise of Capitol’s eq and reverb adjustments.”

Virtually all Beatles authorities, and probably most of their fans, feel that the artwork on Capitol’s Beatles LPs prior to Rubber Soul (at which point their covers started to be the same in the UK and US) was inferior to the designs on their UK covers. When it became widely known that Capitol was slicing and dicing UK releases to make more (and shorter) LPs for the US market, those decisions were rightly criticized as well. Even if some listeners didn’t mind the alterations for the US market, it’s undeniable that the releases were being packaged both without the Beatles’ approval and in a manner at odds with what they wanted. Dexter, perhaps unsurprisingly, sees things his way in his Playback memoir.

“With the dominance of the Beatles came a marked change of attitude on the part of Manager Epstein and his foursome,” he fumes. “No longer could I work felicitously with Marvin Schwartz in designing front and back album covers, choosing the photographs and annotation we thought best. Nor did the bedeviled Epstein allow me a choice of masters to be programmed into album form. Each single, each album, was made to specifications conceived by the Beatles’ organization in London. Artwork was mailed to the Capitol Tower from [EMI’s headquarters in] Manchester Square. So were the back cover editorial notes. None, I think, was an improvement over what we in California had been doing.”

As an aside, Dexter claims in Playback that George Martin told him there would be no soundtrack LP for Help! “because the boys won’t be featuring sufficient songs to fill an LP.” This, in Dexter’s view, forced him to cobble together the US Help! album from seven songs (the ones actually featured in the film) and the quite disposable non-Beatles instrumental music that filled out the American release. That’s a very odd recollection indeed, as the Beatles were writing and working in the studio at their usual industrious pace in early-to-mid-1965, coming up with a full fourteen tracks for the British Help! LP, released at about the same time as its American counterpart. It’s usually assumed the US version of Help! had just seven actual Beatles songs so the leftovers from the UK release (including the American #1 single “Yesterday”) could be parceled out on subsequent Capitol 45s and LPs, in keeping with the label’s usual strategy of spreading product out over more releases to maximize profits. What reason would there have been to keep Capitol’s staff in the dark about what tracks were completed?

(One reason less songs were available to Dexter, by the way, was that Capitol, in its eagerness to rush out as many LPs as possible, used three songs from the UK version of Help! on Beatles VI, released in June 1965 just two months before the US Help! soundtrack. On Beatles VI Capitol also used up another track recorded during the Help! sessions, “Bad Boy” (not issued in the UK until late 1966), as well as “Yes It Is,” the B-side to a song featured on the Help! soundtrack, “Ticket to Ride.” In fact both “Dizzy Miss Lizzie” (used on Beatles VI in the US and Help! in the UK) and “Bad Boy” were specifically recorded for the American market to help fill out Beatles VI so a US LP could be issued prior to the American version of Help! Presumably Beatles VI was compiled by Dexter himself, though he seems oblivious to this as a possible factor for the shortage of material to work from for the Help! soundtrack.)

The Beatles’ worst offense to Dexter, however, took place at a party Alan Livingston gave for the Beatles in 1964. Children of Livingston’s Beverly Hills neighbors, Dexter wrote in the Billboard piece, shouted “for the Beatles to come to the window and be seen. I asked Lennon, who was standing nearest the window facing the children, to move over a few feet and yell a ‘hello.’ ‘Why those bloody little bastards,’ Lennon replied, ‘they try to interfere with us constantly, try to deprive us of our privacy. We’ve had it with ‘em, mate.’ It was an unthinkably rude response. But Ringo and Paul obliged the children.” So unpopular was Dexter’s ill-timed article that Billboard that an editorial in the next issue ended, “We profoundly regret that some readers found it objectionable. We had no such intent and we apologize to those who were offended. Nobody’s perfect—not even Billboard.”

“They got so big-headed,” complained Dexter in his interview with Chuck Haddix. “They were so thrilled with the first few records and the first couple of albums we issued, and they called and thanked me. This was way back when…right after we got ‘em. And they thought that our sound was better on Capitol than on Parlophone.

“A couple years later, why, they went around complaining that Capitol’s sound wasn’t nearly as good as the British sound. And that was printed in all the music publications and…I don’t even like to talk about the Beatles. To me, it was just an unhappy…” he trails off.