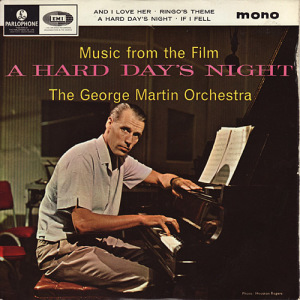

My vote for the Fifth Beatle, if there was such a thing, goes to George Martin, as I wrote about in this previous post. The others in my top ten, based primarily on their contributions to the Beatles’ music, are in another previous post. Here we go through, with briefer comments, fifteen others who made significant contributions.

As I noted in my earlier top ten list, I’m ranking people according to what they added to the Beatles’ legacy, which in my view rests primarily with their music. I’ve made more room on this list for non-musical figures in the Beatles organization, though it still favors musical contributors.

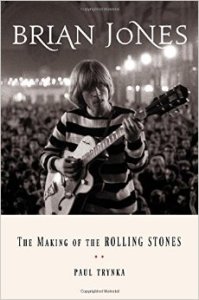

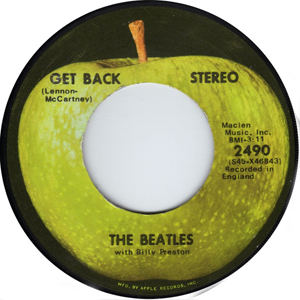

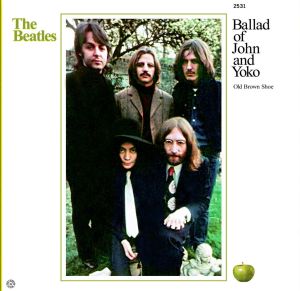

11. Eric Clapton. Who to put at the top of the non-Top Ten, when there are so many contenders for the also-rans of this list? As so many can make cases, why not pick someone who, at least, has a very famous and identifiable musical contribution? That’s Eric Clapton, who played lead guitar on “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.” If you want a good question for your next trivia contest, ask contestants to name all four of the famous rock musicians to play on Beatles recordings. The most likely first answer will be Eric Clapton; many will also guess Billy Preston. The other two are harder (and are farther down this list): Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones (who plays saxophone near the end of the B-side “You Know My Name”) and ace British session keyboardist Nicky Hopkins, who plays electric piano on the single version of “Revolution.”

Clapton’s contribution to the Beatles’ repertoire wasn’t entirely a one-shot deal, although the other instance was more subtle. It was in his garden that George Harrison, skipping business meetings at Apple on one of the first warm spring days of 1969, wrote “Here Comes the Sun.” Also in the late 1960s, they wrote Cream’s “Badge” together, with George adding some guitar to that recording. When George briefly quit the Beatles in January 1969, John Lennon—apparently at least half-seriously—suggested replacing him with Clapton, though this was likely more heat-of-the-moment anger than something he was intent on enacting. Eric and George would be close friends (and occasional collaborators) for much of the rest of their lives, and George’s first wife Pattie would later marry Eric, though that’s beyond the scope of the story of the Beatles as a group.

12. Glyn Johns. If things had gone more according to their initial plan with the January 1969 recordings the Beatles made with the intention of doing an album, Glyn Johns might rate a higher position on this list. Already the top rock engineer in the UK for his work with the Rolling Stones, the Who, and others, Johns was making the transition from engineer to at-least-sometimes-producer. That’s what he was doing on at least some of the sessions for the album that was at that time titled Get Back, which generated much of the material for the LP eventually called Let It Be.

Whether exactly Johns was an engineer or producer at these sessions—at which, the impression is, the Beatles were to at least some extent producing themselves—was unclear even at the time. But he did take a lot of the responsibility for recording the Beatles in a tense month which produced some brilliant, if overall uneven, work. Johns was also the guy first given the task of trying to make an album out of the sessions, which he was doing with acetates even before the sessions had finished.

Had the Beatles gone with one of his mockup acetates (some of which have been bootlegged) of what an album could sound like—which remained faithful to their original intention to record an entirely live LP—it would have sounded better than the actual Let It Be record. Unable to decide on whether it should come out or in what form it should come out, it got delayed in favor of Abbey Road. When Let It Be came out, Phil Spector, co-credited with George Martin and Glyn Johns with production, had added strings to some songs and done some remixing, altering the more back-to-basics goal of the original project.

13. Chris Thomas. Cited in passing on the previous top ten post, Thomas’s contributions to The White Album were greater than was acknowledged at the time, and have been acknowledged since. When George Martin took a vacation in the midst of these tense sessions, his assistant Thomas, just 21 at the time, was asked to in effect act as the unofficial producer of the sessions while Martin was gone. It was (rather like primary late-‘60s Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick) to a large degree a matter of being in the right place at the right time, but the Beatles wouldn’t have stood for an incompetent, and Thomas proved his worth by sticking out the sessions.

Of perhaps greater importance, Thomas also played keyboards on a few songs, though there isn’t absolute agreement which ones feature him. It seems pretty certain, however, that he plays harpsichord on “Piggies” and mellotron on “The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill”; Thomas has said that he also plays piano on “Long, Long, Long,” electric piano on “Savoy Truffle,” and keyboards on “Happiness Is a Warm Gun,” though some sources express uncertainty as to whether his contributions are in the final mixes.

Thomas’s active role in Beatles production might have been brief, but he went on to long and notable career as a producer. Among the records he’s produced are albums by Procol Harum, John Cale, Badfinger, Roxy Music, the Pretenders, and the Sex Pistols.

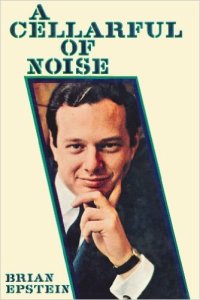

14. Neil Aspinall. Now we get to non-musicians that many other writers would put much higher on their lists. I understand how others would take a different view, but mine is that road managers and personal assistants, such as Neil Aspinall and (see below) Mal Evans, did jobs that could have been done by many others. They did them well; quickly earned and kept the band’s trust; and spent more physical time around them than anyone else, probably even more than Brian Epstein and George Martin. But although they took some occasional token minor roles on Beatles recordings when an extra instrument needed to be played that didn’t demand experience or skill, they were not significant contributors to the Beatles’ music.

Neil Aspinall (center) stood in for an ill George Harrison at a rehearsal for the Beatles’ first Ed Sullivan Show appearance.

Of the two road managers, I would say Aspinall was the more important one as their first, going back to the early 1960s. He also (unlike Evans, who died in 1976) took an active role in the Apple organization for many years, where his background in accountancy came in useful, calling on skills more involved than road managing. It’s been speculated, with hindsight, that Aspinall might have made a better choice for managing the Beatles—or at least acting as their business manager—in the late 1960s than Allen Klein, as he had good, even-handed personal relations with all four members. It was felt he didn’t have the necessary high-level experience, though again in hindsight, he hardly could have done a worse job than the tougher and far more experienced Klein, who did his share to ensure the Beatles broke up. It’s a measure of the respect the Beatles felt for him, however, that he’s one of only three non-Beatles (the others being George Martin and publicist Derek Taylor) interviewed in their Anthology documentary.

15. Mal Evans. More so than Neil Aspinall (who became the Beatles’ road manager in the early 1960s because he was a good friend of Pete Best), Mal Evans lucked into his spot with the Beatles through serving as a bouncer at the Cavern. Big, brawny, and extremely likable, Evans served the group dependably through their touring years, and then for several more as an assistant at Apple. That’s him working the anvil when the Beatles run through “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” in the Let It Be film, and like Aspinall, he can also be heard making minor non-skilled contributions to other Beatles recordings.

Evans did not have the aptitude Aspinall had for organizational work off the road, and didn’t fare as well when the Beatles broke up. He deserves some credit for bringing Badfinger to Apple’s attention and producing some of their early tracks, though “producing” probably meant more keeping an eye on the proceedings than making active musical contributions. He probably would have had a lot to say about the Beatles in the memoir he was working on in the mid-1970s, but he was shot to death by police in Los Angeles in a January 1976 incident that remains controversial.

Although Aspinall seems to have contributed much more heavily to the running of Apple, it’s interesting that in his Rolling Stone interviews with Jann Wenner shortly after the Beatles split up, John Lennon says bitterly, “You see a lot of people, all the Dick Jameses, Derek Taylors, and Peter Browns, all of them, they think they’re the Beatles, and Neil and all of them. Well, I say fuck ‘em, you know; and after working with genius for 10, 15 years they begin to think they’re it, you know. They’re not.” A few questions later, he takes pains to exclude Mal from that list, indicating he held Evans in greater esteem and affection. Nothing else I’ve read, it must be said, intimates that Neil Aspinall took undue credit for the Beatles’ success or basked inappropriately in their glory.

16. Phil Spector. A controversial listing, to be sure. Did Phil Spector contribute to the Beatles, or did he detract from them? Paul McCartney would certainly say Spector’s involvement as co-producer of Let It Be—really a post-producer, as he did some remixing and overdubs on the tracks in early 1970, with only Ringo Starr contributing (and then only slightly)—was a negative. In particular, Spector’s overdubs of strings and female voices on “The Long and Winding Road” is often cited as the final straw in McCartney’s decision to leave the Beatles in April 1970. McCartney even went to the extent of helping generate what was essentially a de-Spectorized version of Let It Be, titled Let It Be…Naked, in 2003.

Spector’s role as Let It Be producer wasn’t as extensive as is sometimes intimated. His overdubs on “The Long and Winding Road” were heavy-handed to the point of being in your face, but he only added strings to a couple other songs, “I Me Mine” and “Across the Universe.” Elsewhere his remixing, I feel, usually neither significantly improved nor diminished the record (though I feel the 45 single mix of “Let It Be,” in which Spector wasn’t involved, was considerably superior). If he wasn’t there, it’s possible the Let It Be LP might not have even come out, as John Lennon and George Harrison in particular felt Spector’s involvement was necessary to salvage an album out of the material.

As noted in previous posts, contributions to the Beatles solo careers don’t count in those listings. But it’s worth noting that Spector made significant and impressive contributions to the early solo records of George Harrison and John Lennon as producer, in a much more sympathetic style than he applied to “The Long and Winding Road.”

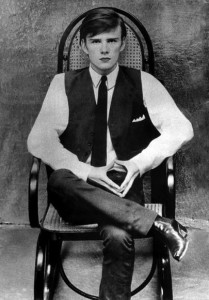

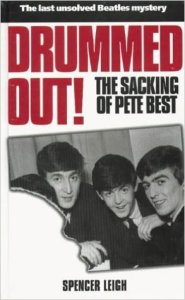

17. Jimmy Nicol. Where do you draw the line with temporary Beatles? Do you include all of the many Quarrymen who dropped out before John, Paul, and George formed the nucleus of the Beatles? How about Chas Newby, who filled in on bass for a few shows when the Beatles returned from their first Hamburg visit without Stuart Sutcliffe? Or Roy Young, who sometimes played keyboards with them onstage in Hamburg? I say you don’t.

But Jimmy Nicol, though never an official Beatle, did play drums onstage with the Beatles at the peak of Beatlemania. He filled in for Ringo, who was ill with tonsillitis, for the first ten days of their mid-1964 world tour. Some recordings (and a bit of film footage) from shows with Nicol survive, and though it’s not too fair to judge a guy who had to join a band at a moment’s notice, he’s not as good as Ringo. Or at least, it can certainly be stated that his style didn’t fit in as well with the Beatles as Ringo’s did. He’s too busy and overplays. He seems to be settling down by the time of the final unofficial live recording of the Nicol lineup (from June 12 in Adelaide, Australia). But the band were immensely relieved when Ringo rejoined a few days later, both to have Starr’s musical assets and to have their buddy back instead of a stranger.

Although this is the only thing Nicol’s remembered for, he did have a long performing and recording career, going back almost to the dawn of British rock’n’roll, and extending a few years past the Beatles. You might not think it possible to make a book out of his life, but of course there is one. The obscure The Beatle Who Vanished has his story, even if it has to be stretched quite a bit to fill up 238 pages.

18. The Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Another selection bound to attract criticism. Just as it’s certain McCartney views Spector as more of a negative than a positive, it’s likely that Lennon would view the Maharishi in a similar light.

But if the Beatles hadn’t met and then traveled to India to study with the Maharishi, The White Album would have certainly been different. It’s not just because experiences in India specifically inspired the creation of a few of the songs—not just “Sexy Sadie,” a thinly veiled attack on the Maharishi, but also “Dear Prudence,” about fellow meditator Prudence Farrow, and “The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill,” an American hunter they met in India.

More subtly, and less famously, the visit to India—although it ended badly, with none of the Beatles staying for the duration of their intended course with the Maharishi—gave them an environment conducive for writing plenty of songs. First because, for the first time in about five years, they were isolated from the day-to-day hysteria of a public and press clamoring for their attention. Second because, as they were often meditating, that—at least it’s been credibly theorized—gave rise to the surfacing of many subconscious creative ideas that found their way into their songs. And third, since they had only acoustic instruments with them, they could give some of the songs an interesting folky flavor. Which leads into the next listing…

19. Donovan. Briefly considered a creative and commercial peer of the Beatles in the late 1960s, Donovan was friendly with them, especially Paul McCartney. He contributed the “sky of blue and sea of green” lyric to “Yellow Submarine.” That alone wouldn’t be enough to get him on this list, but he was also with the Beatles when they studied transcendental meditation with the Maharishi in India. It’s been speculated that he was there in part because he was chasing George Harrison’s sister-in-law Jenny Boyd (the subject of Donovan’s hit “Jennifer Juniper,” later to marry Mick Fleetwood). But that’s as good a reason as any to suspend your career for a couple months to fly halfway around the world.

“While the Beatles and I were in India they wrote the White Album songs,” Donovan told me in an interview for the book Jingle Jangle Morning: Folk-Rock in the 1960s. “It was obvious The White Album would have a distinctive acoustic and lyrical vibe. Paul, John, George, and I all had our acoustic guitars with us. George would later say that my music greatly influenced The White Album. I played all my styles, and the Beatles were exposed to weeks of Donovan. John was influenced to write romantic fantasy lyrics on the two songs he wrote, ‘Julia’ and ‘Dear Prudence,’ after my teaching him my finger-style guitar method. He was a fast learner.”

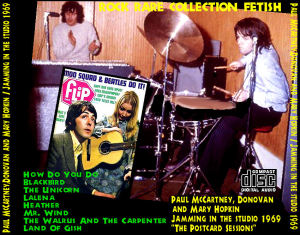

In late 1968, an unreleased tape captures Donovan and Paul McCartney informally playing and singing a few tunes together acoustically at a Mary Hopkin session. More pleasant than remarkable, it’s sort of an adult version of the ditties Donovan put on his 1967 children’s record, For Little Ones. As a final Beatles connection worth noting, while in India, George Harrison wrote a verse for Donovan’s hit song “Hurdy Gurdy Man” that was not used in the studio recording; Donovan in turn helped George write “Dehradun,” an unreleased version of which Harrison recorded in 1970.

Bootleg that includes the informal session between Paul McCartney and Donovan (more commonly dated to 1968, though this gives it a 1969 date).

20. Andy White. The only guy besides Ringo and (when Ringo quit the band for a few days during The White Album) Paul to play drums on a Beatles record, Andy White was the session musician that George Martin used when the group cut their first single, “Love Me Do”/“P.S. I Love You.” As it happened a take with Ringo was used on the single (though he’s playing tambourine, and White drums, on the LP version), but Starr was relegated to maracas for “P.S. I Love You.” When the group recorded an early version of “Please Please Me” on September 11, 1962 (the session where they finished up their first single), White was also on drums, as can be heard on the version released on Anthology 1.

These are pretty meager contributions on which to claim the role of notable associate. But White could nonetheless say he played on a Beatles record—and on one of the band’s core instruments, not as a session musician on something the Beatles never or seldom played themselves. For what it’s worth, though, the drum parts he plays on “Love Me Do” and “P.S. I Love You” aren’t that prominent or interesting. And when he takes more of a presence on “Please Please Me,” his drumming is not very good—a la Jimmy Nicol later, it’s inappropriately busy. Kudos to George Martin for letting Ringo play forever after, even he didn’t have the conventional studio chops of session veterans like Andy White, as his style was a far better fit for the band.

21. Klaus Voormann. Had Klaus Voormann learned the bass a little earlier, he would have made a reasonable replacement for Stuart Sutcliffe in mid-1961. Though a bit older than the Beatles, he would have fit in okay visually and personally, despite not speaking English well at the time. Of course, had he not stumbled upon the Beatles in Hamburg’s red-light district, he wouldn’t have become interested in rock music at all, let alone pick up the bass.

By the time Voormann became proficient, the Beatles were well on their way to fame as a foursome. But Klaus kept in touch with them, moved to England, and joined other rock groups, working his way up to one of the bigger British bands, Manfred Mann. Of most note, he designed their Revolver sleeve, putting his art school background to appropriate use.

“You can imagine how I felt after having heard some of the songs that were going to be released by the Beatles soon,” Voormann told me in a 2007 interview about the Revolver sleeve. “A new trend was going to be set, and there was little me having to come up with something just as daring, or at least give the record buyer a lead to what they were getting themselves in for. Brian Epstein was scared the fans might turn their back on the band and say, ‘What happened to our Beatles? I want them the way they were before.’ But when Brian saw the Revolver cover he said, ‘Klaus, your cover manages to build the bridge from the music to the fans.’”

That—along with introducing the Beatles to photographer and friend Astrid Kirchherr in Hamburg—is enough to get Voormann onto this list. Voormann would also play bass on solo recordings by John Lennon (the first of those being the Live Peace in Toronto album, done in September 1969 when Lennon was still in the Beatles), George Harrison, and Ringo Starr. He’s on “I’m the Greatest,” the John Lennon-penned Ringo Starr track also featuring Lennon, Harrison, and Billy Preston. He was also the bassist in the nonexistent group most of the Beatles were rumored to be forming in the early 1970s, the Ladders, who would have also included Lennon, Harrison, and Starr. Which would have made him the Fourth Beatle of sorts, but the Ladders never actually formed.

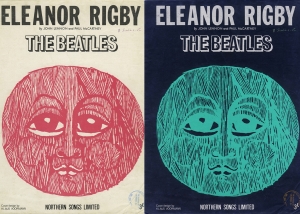

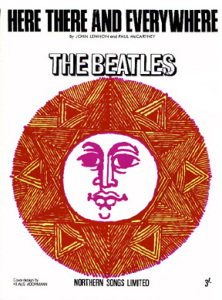

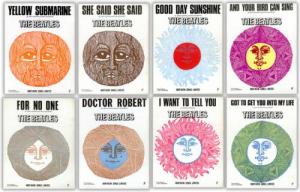

It’s pretty well known that Voormann designed the Revolver cover, but it’s not so well known that Klaus also designed the covers for sheet music of Revolver songs. Here are a few of them:

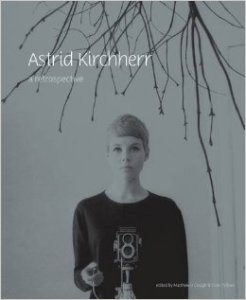

22. Astrid Kirchherr. The only woman besides Yoko Ono to make this list, Kirchherr was vital to the creation of the Beatles’ image in the early 1960s. First she did so by taking the first truly first-class and striking pictures of the group in Hamburg. She has also been credited with devising, or at least getting Stuart Sutcliffe to adopt, the Beatles hairstyle. The other Beatles followed (Pete Best excepted), giving them their top early visual trademark. Aside from getting engaged to Sutcliffe (though they didn’t marry as Stuart died in April 1962), she was also simply a valued friend to the Beatles as they played in a foreign land to strangers in their Hamburg days. Like her ex-boyfriend Klaus Voormann, she had an artistic and bohemian sensibility with which they felt much more at ease than they did with the usual patrons of the Hamburg clubs they played.

It is strange and unfortunate that Kirchherr—discouraged by the lack of interest in her pictures that didn’t feature the Beatles—failed to pursue photography more seriously after the Beatles rose to fame. One certainly thinks she could have photographed an album cover or two for them. Robert Freeman’s photo for With the Beatles, whether intentionally or not, features half-lit faces similar to some of Kirchherr’s shots of the group. But other photographers would take the bulk of the Beatles’ pictures from 1963 onward, including Freeman, Robert Whitaker, Dezo Hoffman, Michael Cooper (for the Sgt. Pepper album), Ethan Russell (near the end of their career), and others.

23. Derek Taylor. Here you get to the point where fifth Beatles get less directly involved or less exciting to detail. Yes, Derek Taylor did a lot of work for them as a publicist near the outset of Beatlemania, and then as a press officer for Apple in the late 1960s and early 1970s. As PR guys went, he was probably the most interesting and colorful, if given to over-florid prose in his press releases. But did you really have to work too hard to publicize such a commercial commodity as the Beatles? Would their career have been too different if he hadn’t been there?

I’d say no, though he was good for some stories in Beatles histories, having known them better than most people in their inner circle. Which is probably why, as previously stated, he was one of the three non-Beatles interviewed for the Anthology documentary. It’s a shame, however, that his limited-edition 1983 memoir, Fifty Years Adrift, has never been issued in an affordable edition for the general public.

24. Nicky Hopkins. Now that we’re past the point in this list at which there were really major contributors to the Beatles’ legacy, how to round this out to a list of 25? How about by listing a couple guys who, though their interaction with the group was fleeting, you can actually hear on their records? Or at least one record, which is the case with Nicky Hopkins? He played on lots of discs by other British ‘60s artists, almost to the point where he could be considered a fifth member of the Who for their debut album My Generation. And he plays electric piano on the Beatles’ “Revolution”—the “fast” single version, not the one on The White Album.

When Paul McCartney and John Lennon sang uncredited background vocals for the Rolling Stones’ “We Love You” at a June 1967 session on which Hopkins played piano, Nicky later recalled, that led to the invitation to play on “Revolution.” According to a Hopkins quote in Julian Dawson’s Nicky Hopkins: The Extraordinary Life of Rock’s Greatest Session Man, “There weren’t really any instructions, except where they wanted the piano to start and I basically just played some blues stuff and we did it in one take. I’d have preferred to do it again, but they were fine with that. I remember I was surprised at the amount of distortion; it was John’s rough side coming out and it sounded wonderful. I quickly got tuned into hearing it that way and it still holds up great—a wonderful record!”

As to why he wasn’t asked to play on other Beatles sessions, according to another Hopkins quote in the same book, Lennon told Nicky, “We just thought you were too busy, with the Rolling Stones and all.” As some compensation, Hopkins played on solo releases by all four Beatles, his most memorable contribution perhaps being to George Harrison’s 1973 #1 single “Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth).”

When the Beatles did promo films for “Revolution” in late 1968, they did live vocals, but used the backing track from the record. If anyone tries to tell you it’s not, ask them why you can hear an electric piano—the part played by Hopkins—even though a piano isn’t on the stage.

25. Brian Jones. Brian Jones was known more as a guitarist in the Rolling Stones (whom he left in June 1969, dying less than a month later) than anything else. But he played many instruments, and before he’d gotten into the blues and rock, he’d played jazz. It was still strange that, when he was invited to lend a hand to a Beatles session, he showed up with an alto saxophone, rather than a guitar or something else more in line with what he usually played, like a harmonica.

Characteristically, instead of getting unsettled, the Beatles were unfazed and made use of what he’d brought to the party. Jones’s rather tremulous sax is heard in the final part of their goofy B-side “You Know My Name,” adding appropriately woozy jazz to the lounge music satire. If you’re wondering how he could have guested on a track used on a 1970 single, remember that the first sessions for “You Know My Name” were done in 1967, Jones playing sax on the one on June 8.

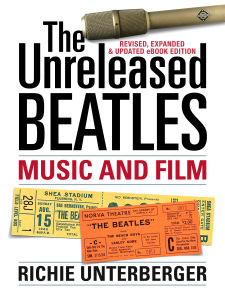

- Critical description of all known unreleased Beatles recordings, their most crucial unissued film footage, and more. Updated with 30,000 more words to reflect newly circulating material and additional information that’s come to light since the original edition. Click here or on the cover image above to order through Amazon.