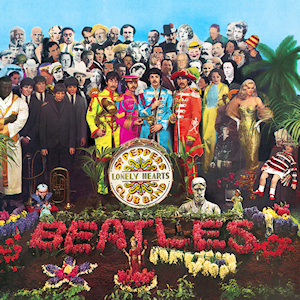

What do you say about an album that, back in the year in was issued, would have topped many best-of lists, but has become so over-familiar that even a six-disc expanded version isn’t as exciting as it could be? The six-disc deluxe box of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is a big step in the right direction in the packaging of the Beatles’ catalog, which until this 50th anniversary edition had not taken the obvious step of expanding their classic albums in reissued formats. This one has the stereo and mono versions, plenty of outtakes, the classic cuts from the “Strawberry Fields Forever”/“Penny Lane” single (originally intended to be used on Sgt. Pepper), and the audio on Blu-ray/DVD discs if that rings your chimes. But the extras aren’t as exciting as they are on some other box set editions of classic vintage LPs, and the fans most interested in the bells and whistles probably already have a good deal of this in their collection, sometimes many times over.

That doesn’t mean I don’t care about Beatles material that hasn’t been available before. With The Unreleased Beatles: Music and Film, I wrote a whole book on that subject. But as I noted in that book, 1967 might have been the least interesting year of the Beatles’ career (if we focus on their core 1962-69 era) in terms of material that was unissued at the time. No longer touring, they were focusing on studio recording, and in those recordings, building up tracks layer by layer. That means the different versions of songs they recorded for the LP—which form the bulk of the three dozen or so extra cuts on the box (counts vary according to whether you might consider a “2017 mix” previously unreleased)—aren’t all that different from the album versions we’ve heard all these years. Sometimes you essentially just get the backing track or elements of a track, which is interesting, but not so much that you’re likely to enjoy them over and over.

Whatever edition of Sgt. Pepper was issued (the 50th anniversary CDs also came in two-CD format with less bonus tracks), media coverage focused on the stereo remix by Giles Martin, George Martin’s son. I seem to be one of the critics least excited by ballyhoed remixes; it’s good, but it’s not that stupendously different from the original, and the original always sounded pretty good in the first place. The 1992 TV documentary on the DVD/Blu-Ray discs (The Making of Sgt. Pepper), featuring interviews with Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, George Harrison, and George Martin (who brings up separate elements of some tracks at the mixing board) is good, but long available on bootleg. The 144-page hardback book might be the best reason to buy the box, as it hasn’t been available before and can’t be easily bootlegged, and is pretty well done, even if the details on some tracks (like the bonus ones on the mono CD) could have been better. And for all its size, the box is missing a few bootlegged or known-to-exist items—the avant-garde “Carnival of Light” outtake, John Lennon’s home demo of “Good Morning Good Morning,” and Lennon’s home recordings of “Strawberry Fields Forever” (not to mention “Only a Northern Song,” recorded during the sessions, but not released until Yellow Submarine)—that would have made the box more definitive, if more expensive.

You can probably tell I don’t feel like the $150 or so this box cost (prices vary according to where you buy it and the shipping, if that’s involved) quite justified the price tag. But don’t get me wrong – the quality even on the oft-circulated stuff is better than the bootlegs; a few of the previously uncirculated tracks (like the “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” where Lennon has a mechanical vocal, changing to a more rapid and natural phrasing at McCartney’s suggestion) are pretty interesting, if not phenomenal; and the overall packaging is of a commendably high standard, even if there are a few questionable decisions and omissions. Hopefully there will also be a deluxe box for The White Album’s 50th anniversary, especially as there are much more, and much more interesting, extras to choose from (especially if you count the couple dozen or so demos they did at George Harrison’s home shortly before the sessions started). And then maybe they’ll finally go back to all of their albums to construct deluxe editions.

In the bulk of this post, I’m not going to focus on a track-by-track rundown. (Brief commercial interruption: I describe each “bonus track” on the deluxe box that wasn’t released back in 1967 in the updated ebook version of my book The Unreleased Beatles: Music and Film.) Nor will I detail the merits of the Giles Martin remix; there’s been enough of that on Facebook, NPR, and classic rock magazines. Instead, here are a few more obscure aspects of the reissue that fanatics might find interesting.

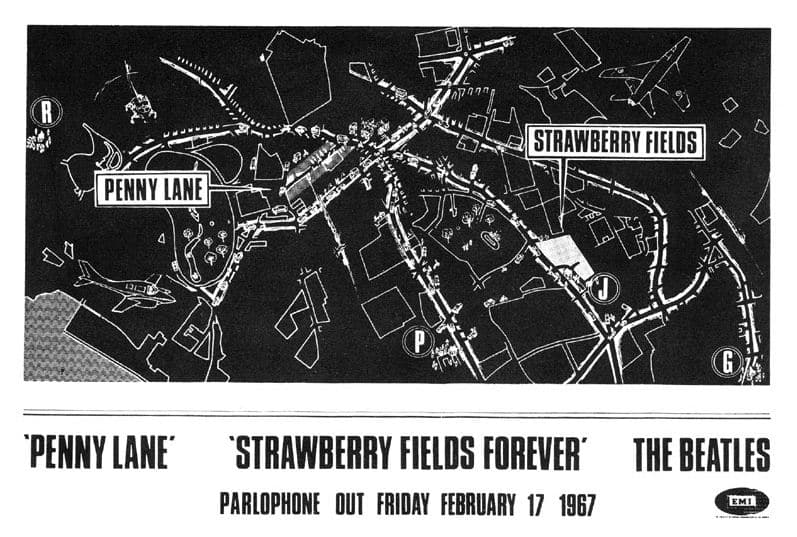

What’s been added: Besides the many bonus tracks, the deluxe edition has also added “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane.” It wasn’t well known at the time—though it’s pretty well known now, even if you’re not a Beatles obsessive—that both of these tracks were recorded early in the Sgt. Pepper sessions, and originally intended for the album. But pressure from Brian Epstein and EMI resulted in both songs getting issued in February 1967 on a single, in part because they were desperate to get a Beatles record on the market, as none had appeared for—gasp—six months! That’s nothing today, but that was the longest gap of their career up to that point, and hunger to quell rumors the Beatles were breaking up (as they’d taken the drastic step of retiring from live concerts) also played a part.

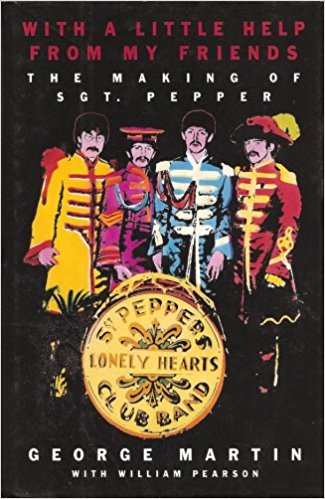

Wrote George Martin in his book With a Little Help from My Friends: The Making of Sgt. Pepper (written with William Pearson): “It was the biggest mistake of my professional life.”

Let’s look at the full context of that remark, from the same book:

“Realizing how desperate Brian was feeling, I decided to give him a super-strong combination, a double-punch that could not fail, an unbeatable linking of two all-time great songs: ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ and ‘Penny Lane.’ These songs would, I told him, make a fantastic double-A-sided disc—better even than our other double-A-sided triumphs, ‘Day Tripper’/‘We Can Work It Out,’ and ‘Eleanor Rigby’/‘Yellow Submarine.’

“It was the biggest mistake of my professional life.

“Releasing either song coupled with ‘When I’m Sixty-Four’ would have been by far the better decision, but at the time I couldn’t see it.”

A few observations here:

It’s hard to see where “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane” would have fit onto Sgt. Pepper, even though each of them were better as individual songs than any on the LP, except possibly for “A Day in the Life.” Maybe that’s because we’re so familiar with the thirteen songs that did make it onto LP, and the exact sequence of those songs, that it’s now hard to imagine the album any other way.

I guess “Strawberry Fields” could have ended side one and “Penny Lane” started side two, though the heart-stopping sudden climax of “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite” is hard to beat for a side-ender, especially in the days when you had to get up and actually flip the record. But that would have compromised the sound quality of the vinyl LP, in the days when even 45 minutes of music was pushing it. And then, which two songs do you take off? They’re all important to establishing the record’s mood, even lesser ones like “When I’m Sixty-Four.”

Speaking of which, I think it would have been a disaster to put “When I’m Sixty-Four” on a B-side, as it was clearly inferior to either “Strawberry Fields” or “Penny Lane.” More importantly, “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane” were a better pairing than any Beatles 45 boasted—and perhaps any 45 by anyone boasted. They were both about Liverpool childhood, in very different ways; they coupled one of John Lennon’s best songs (“Strawberry Fields”) with one of Paul McCartney’s best (“Penny Lane”); and the single had a distinctive picture sleeve.

This wouldn’t have been possible with “When I’m Sixty-Four.” And if you can only choose “Strawberry Fields” or “Penny Lane” for the LP, how can you possibly make a good choice of one over another? And if you can’t use “When I’m Sixty-Four” for the LP, doesn’t that throw off Sgt. Pepper’s balance, as one of its virtues was encompassing so many styles, for which “When I’m Sixty-Four” represented vaudeville?

No one I’ve come across—and just about everyone I know is familiar with Sgt. Pepper—has ever complained about missing “Strawberry Fields Forever” or “Penny Lane” on the album. George Martin’s about the only one I’ve heard express regrets. Along the same lines, George Martin was vocal, quite a few times, about wishing the Beatles would boiled down The White Album from two LPs to a much stronger disc. But very few other people would agree with him on that. And even if they do, no one would agree on which half of the songs to discard.

Maybe if it had been the CD era and sound quality on a longer album had not been an issue, putting “Strawberry Fields” and “Penny Lane” on Sgt. Pepper would have been the right call. All things considered, however, back in 1967, it was the right call. And now that it’s the CD era and there are big expensive expanded box set editions of classic albums, it’s the right call to add the tracks, separated from the main thirteen songs so that it doesn’t change the sequence of the core LP.

Before this 50th anniversary release, by the way, I saw some comments on social media about what a bad idea it would be to add “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane.” Maybe those comments grew out of fears those songs would be inserted into and change the album’s main running order, which I agree would have been a mistake. So it’s worth emphasizing that they are separate from the core LP (as they are on the more modest two-CD deluxe edition).

If their very presence anywhere is considered bothersome, that seems as ridiculous as the complaint I once heard from someone who disliked any bonus tracks on CD reissues of albums, finding them distracting and injurious to the integrity of the original LP. If you really do find CDs with bonus tracks a ripoff—a concept about as sensible as complaining that free health care is too expensive—you can, of course, simply not play the extra cuts, or better yet, not buy these reissues.

What’s missing: Can there be much missing from a six-disc deluxe edition, with several dozen bonus tracks, some of which haven’t even been bootlegged? Yes, if we’re looking at the time frame between mid-September 1966 (when Lennon made his first informal composing tapes of “Strawberry Fields”) and when the album was finished on April 21, 1967. That’s even if you don’t count their 1966 Christmas fan club disc or home recordings (most by John) that were obviously too chaotic and lo-fi to merit serious consideration. Here are the most notable absentees:

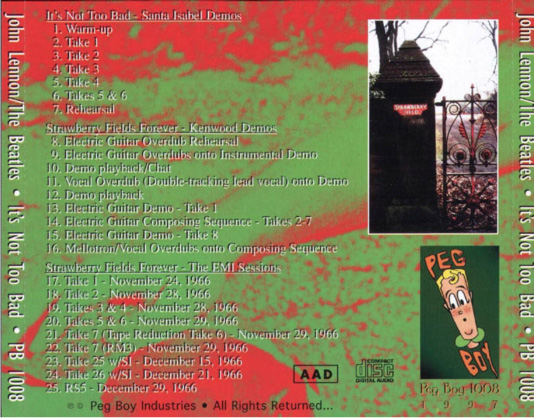

“Strawberry Fields Forever” home tapes: John Lennon made quite a few tapes of “Strawberry Fields” in the two months before the Beatles started working on it at the studio in November 1966, some at home, and some (the earliest) in Spain, where he was filming his role in How I Won the War. It’s true it’s pretty repetitious to hear all of these (plus the various different recordings the Beatles made of the song in the studio before finalizing the track) all at once. But it’s historically fascinating, especially as it evolved from a much simpler near-folk song in its earliest solo acoustic versions. And they do circulate unofficially, on CDs such as the one below:

“Carnival of Light”: One of the most discussed Beatles studio outtakes that has never circulated, this wasn’t ever intended for Sgt. Pepper, but recorded on January 5 for use at a multimedia event of the same name at London’s Roundhouse on January 28 and February 4. From its description in Mark Lewisohn’s book The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions, it sounds heavily avant-garde, and perhaps tuneless. Hints have been dropped for years that it would find release. But its non-appearance on this deluxe box seems to indicate it might never appear—and that it might just not be very good and listenable.

“Good Morning Good Morning” home demo: Of the many home tapes John Lennon made in the late 1960s, this is the only one of a Sgt. Pepper song. In fact, it’s the only home recording of a Sgt. Pepper song. It’s just a bit over a minute long, and the chorus hasn’t been worked out, but it’s still interesting, in part because he chuckles after the fragment of the chorus (and the people he sees are “fast” rather than “half” asleep). Maybe home tapes were considered off-limits for a set featuring only EMI recordings, but that didn’t stop some such tracks from getting included in the Anthology series in the mid-1990s.

“Only a Northern Song”: The only real song recorded during the Sgt. Pepper sessions that didn’t make the album, aside from the “Strawberry Fields Forever”/“Penny Lane” single. Sometimes people ask me what my least favorite Beatles song is, and while I don’t have many contenders (as I like almost all of their songs), this is among the ones I mention. About thirty years ago I did come across someone who thought it was great, but I’ve never met anyone else who shares that opinion. Actually I’ve heard few opinions voiced about this George Harrison composition whatsoever—it did find a place on the Yellow Submarine album, but many listeners simply don’t remember it well, or at all.

“Only a Northern Song” was rejected for Sgt. Pepper. George Martin seems to have been particularly unenthusiastic, remembering in With a Little Help from My Friends, “I groaned inside when I heard it.” He suggested Harrison try to come up with something better, which the Beatle did with “Within You, Without You”—not only a better song, but an infinitely better fit for the Sgt. Pepper LP.

It’s hard to imagine where “Only a Northern Song” would have fit, had the tune simply been accepted as George’s contribution. It seems like it would have brought the carnival-like mood to a dead stop, with its rather careless half-baked swirl. It wouldn’t be a great fit even for the Sgt. Pepper deluxe box, where I suspect few miss its absence. And unlike the other recordings in this section, you can get it on another official release, Yellow Submarine, in any case.

So much is said in silence: Many times, I’ve read that there is no silence or no gap between tracks on Sgt. Pepper. This was mentioned in some writing on the LP shortly after it was released, and it’s still often referred to as a feature of the album. Kevin Howlett’s essay on the record’s “Songs and Recording Details” book in the deluxe box, for example, states:

“…the album sounds like a unified work. The elimination of the usual few seconds of silence between tracks helps to create this impression. The songs flow together without a break, like a surreal music hall variety show. Interestingly, the idea not to have ‘rills’ on the record had been considered before Sgt. Pepper. A month ahead of starting work on Revolver, in an interview published in NME, John discussed ideas for the group’s next album. ‘We wanted to have it so that there was no space between the tracks—just continuous. But they wouldn’t wear it [sic].’ The group was eventually allowed to carry out that idea, not only on Sgt. Pepper, but also on subsequent albums.”

I think I was around eight years old (which would have been 1970) when I first read about there being no silence between the tracks in a couple books. Even then, that assertion puzzled me. There are just three instances when there is no silence: when the title track segues into “With a Little Help from My Friends” as they sing “Billy Shears”; when the animal noises in “Good Morning Good Morning” turn into the guitar that starts the reprise of the title track; and when the cheers at the end of the reprise fade and “A Day in the Life” starts.

Otherwise, there’s silence between the tracks. Very short gaps of silence, yes, lasting just a couple seconds or less. But they’re there. The other tracks don’t segue into each other, or slam right against each other, as they do in my favorite album in which this occurs, the Mothers of Invention’s We’re Only in It for the Money (which of course was in part a Sgt. Pepper satire). I think the Mothers’ 1967 album Absolutely Free, released at almost the exact same time as Sgt. Pepper, was the first rock LP in which there was truly no silence separating tracks.

For what it’s worth, on my vinyl copy of Sgt. Pepper, you can clearly see thin bands separating all of the tracks (even the ones that blend into each other), as you can on most LPs. Granted, it’s not a first pressing, but I don’t recall seeing other copies of Sgt. Pepper with no thin separating bands. (Update: just after this post went up, Peter Bochan (see comments section) clarified: “I got the first edition Sgt. Pepper shipped over from UK. It didn’t have visible track separations, if you looked at it closely you could see some of the songs ending by way of intensity of the groove patterns. US copy had tracks.”)

This is far from the most controversial issue surrounding the Beatles or even Sgt. Pepper, but I think the continued reference to no silence between the tracks is simply inaccurate. For that matter, although most of side two of Abbey Road is commonly described as a continuous medley starting with “You Never Give Me Your Money” and ending with “The End,” there is in fact a definite, if short, silence between “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window” and “Golden Slumbers.” I don’t know how these things get entrenched, but once they do, it’s hard to stop them. (Also note some tracks on The White Album fade into each other without silent breaks, like “Back in the USSR” into “Dear Prudence” and “Revolution 9” into “Good Night,” but that’s never referred to as an LP without separating tracks.)

One more silence-related issue to bring up about Sgt. Pepper: the original UK issue had a bit of gibberish in the run-out groove after “A Day in the Life” ended (as well as a high-pitched whistle only dogs could hear), but the North American one didn’t. The book in the deluxe box explains how this might have happened.

As early as April 19, well before Sgt. Pepper’s release, some US radio stations somehow obtained copies of some tracks and began broadcasting them without authorization. Capitol Records wanted to counteract this by issuing the LP as soon as possible, and a cable from EMI indicates the mono tapes were sent on April 21, with the stereo ones hoped to follow the next day. “At this stage, the target release date was 8 May 1967,” Kevin Howlett writes (though it wouldn’t come out until the beginning of June). “The haste to supply Capitol with tapes partly explains why the American version of Sgt. Pepper did not include the material embedded in the run-out groove of the British record.” (Don’t worry, it’s on the 50th anniversary reissues.)

I honestly don’t remember discussing this run-out groove with anyone in my lifetime. My opinion is that on a CD, it’s much more effective to just have the memorable final piano chord of “A Day in the Life” (and the whole album) fade into silence, without anything to follow. And maybe that’s how it should have been on all editions of the LP, too.

ADT on “She’s Leaving Home”: ADT refers to “automatic double-tracking,” a device often used on Beatles recordings to thicken sounds, especially lead vocals. One of the more interesting bonus tracks on the deluxe box is the “first mono mix” of “She’s Leaving Home,” which has four cello notes at the end of each chorus that were edited out of the final version. In addition, the opening notes on the harp, played by Sheila Bromberg, are treated with ADT, giving them a strange artificial effect that was not used on either the mono or stereo versions on the final album.

In 2011, Bromberg was interviewed by BBC One television about playing on the track. The brief segment is interesting, as I don’t recall her discussing this anywhere else. She recalls that Paul McCartney had the musicians (none of the Beatles played on the track) try several different ways of playing the song, and had trouble verbalizing how he wanted Bromberg to change her part, especially as he didn’t write or read music. After all those attempts, it was the first take that ended up being used.

In the segment, the BBC interviewer states, “When Sheila heard the track, she realized they’d used the first take. The sound McCartney had been after, a doubling effect of her playing, had been created by the engineers.” “That’s how they got that sound. That’s what he was after. Yes!” exclaims Bromberg.

It makes a good story, but the “doubling” or ADT effect was not used on either the official stereo or mono versions. You can clearly hear the difference on the intro of the “first mono mix.” As Mark Lewisohn writes in The Beatles Recording Sessions, “As an experiment, ADT was applied to the song’s opening harp passage on [mono] remix one, but the idea was dropped after that.”

So why would Bromberg have thought the track was “doubled”? Is it even possible she was accidentally played the then-unreleased “first mono mix” when interviewed for the program?

Another Beatle myth exploded: The book in the deluxe box set doesn’t have much information that’s different to how the genesis of Sgt. Pepper has usually been reported. Here’s the most important exception:

Almost since the time it was released, it’s generally been accepted that “Strawberry Fields Forever” was edited together from two different takes. These were performed in different keys and different tempos, so it would have been virtually impossible to do this with 1966 technology without sounding awkward. George Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick managed to do so, however, by speeding up take 7 and slowing down take 26. Miraculously, the keys and tempos now matched, almost as if by divine miracle. Takes 7 and 26 are both on the deluxe edition.

Or, at least, that’s how it was usually reported, as it is in The Beatles Recording Sessions. However, the book in the Sgt. Pepper box gives a different account. Here, Kevin Howlett writes that “the speed of take 26 was reduced by 11.5 percent and, as John’s voice was lowered by over a tone in pitch, the effect was created of a sleepy slur as he sang. The speed of take seven was not altered.”

Well, isn’t that a cold shower. I’ve told the story about both takes being altered and matched with calm authority at least half a dozen times when I’ve taught a course on the Beatles. Now I can’t tell it anymore. But it does go to show that Beatles mysteries continue to be untangled fifty years after the fact, buried in the deep recesses of EMI’s tape vaults.

The previously unreleased material on the Sgt. Pepper box, along with all of the other recordings the Beatles made that weren’t released while they were active, are written about in detail in my book The Unreleased Beatles: Music and Film.