The first two posts in this three-part series examined some mysteries surrounding the early career of the Wailers, in the decade before they signed to Island Records. Going in chronological order, this final post looks at the period right before they signed to Island, when they were in England in 1972.

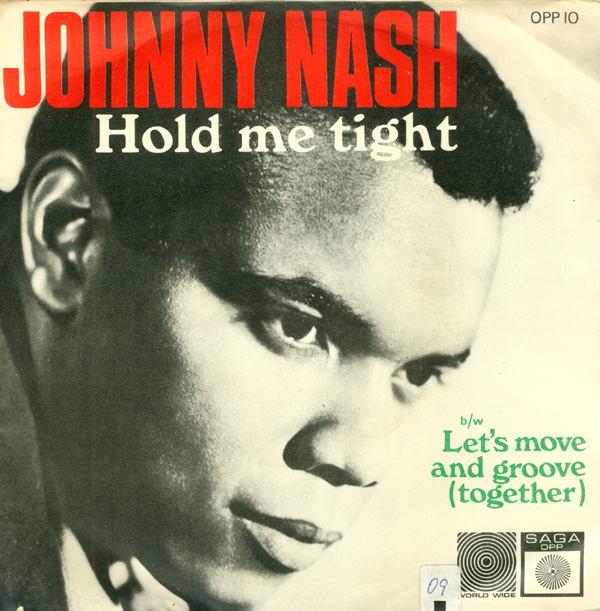

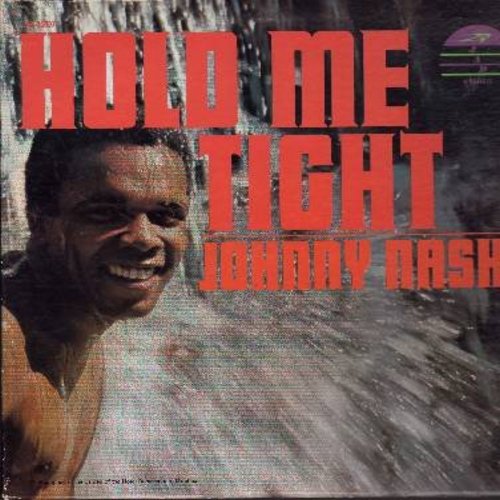

The reason for Bob Marley’s relocation to London early that year was straightforward enough. Although it was coming up on its fifth year in early 1972, Bob’s association with manager-of-sorts Danny Sims and his fellow client Johnny Nash hadn’t yielded much in the way of tangible results. Yet for all his problems with them, they remained his only lifeline to the international music business. Now there was a chance Bob could sign with CBS Records’ Epic subsidiary, for whom Nash was now recording. In mid-February, Marley flew to London, not only to play on the album Nash was recording there, but also to do some tracks for CBS under his own name.

Marley went without the other Wailers (or, for that matter, his wife Rita, who was an honorary Wailer of sorts and had sung on quite a few of their records since the mid-1960s). This seems to indicate that Sims and Nash viewed him as the group’s primary asset, and perhaps sole asset in which they were truly interested. They’d signed Bob, Rita, and Peter Tosh to a songwriting/publishing deal back in 1968, but in 1971, Bob was the only one they’d flown to Sweden to work on songs for the soundtrack to an obscure film in which Johnny Nash starred. While in Sweden, Bob didn’t even mention the other Wailers to a Texan keyboardist also working on the soundtrack, Rabbit Bundrick. Maybe he was thinking of a solo career, or at least considering it as an option.

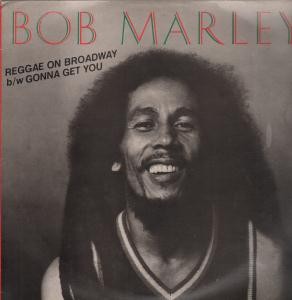

Marley recorded about half an album’s worth of tracks for CBS in London in 1972, but just a couple of them came out on a flop single. Sometime after this, the other Wailers—not just Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingston, but also bassist Family Man Barrett and drummer Carlton Barrett—were flown over to join Bob. As is typical with the imprecision surrounding many Marley dates, it’s not known exactly when this happened in 1972; some accounts give the impression this occurred in the spring, and others quite a bit later in the year. But they did go over to London, and were definitely there in the latter part of the year, when they approached Island Records.

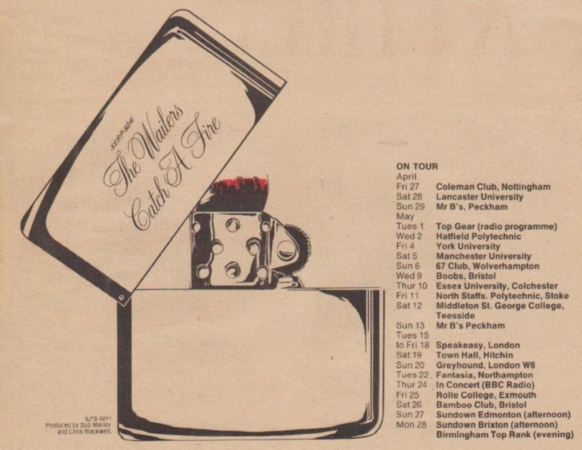

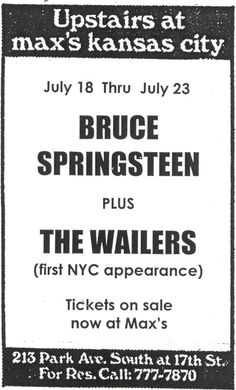

It’s unclear, however, why the Wailers were flown over, presumably at Sims’s expense. The logical reason would seem to be that he and the Wailers hoped to build a British following by playing live shows. However, they barely performed at all. There was just one proper Wailers concert, and Marley and Tosh played a benefit at a London school to raise money for a new swimming pool, but that was probably hardly the gig they had in mind when they left Jamaica. Marley did some shows as a support act for Nash without the other Wailers, which couldn’t have been great for team morale, or do much to counteract the impression that Sims was mostly interested in Bob, not Peter or Bunny.

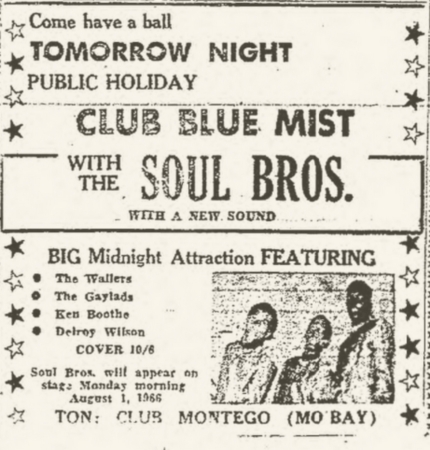

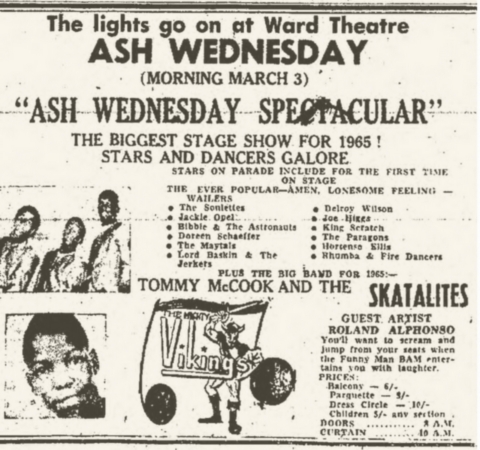

It’s been suggested that the main reason the Wailers were there was to learn stagecraft by observing Johnny Nash’s British shows. This seems yet odder than not having them play much on their own. First, it would have been expensive to fly the Wailers over and give them enough support (if basic in nature) to live in London for an extended period. Doing that so they could watch Johnny Nash seems like a rather frivolous investment. Also, the Wailers had been together since the early 1960s, and performing live concerts for at least some of that time, though timelines as to how many shows they did are about as cloudy as most other aspects of their early career. Even if they didn’t do all that many gigs, after a decade or so, how much more could they learn from Nash, and did they need to follow him around on tour for such an extended period as part of their education?

Maybe Bob asked, or demanded, that the other Wailers be flown over if he was to continue to try and make headway in Britain. Maybe part of the purpose was to record the Wailers in British studios, as Danny Sims did arrange for the Wailers to cut five tracks at CBS (including “Stir It Up” and four other songs that they’d re-record for Catch a Fire). But those weren’t issued, and there’s nothing to make one believe Sims knocked himself out trying to get the Wailers a band deal. Indeed, part of the reason they ended up at Island was because they were frustrated with their management, and took things into their own hands, approaching Island’s Chris Blackwell without the help of Sims.

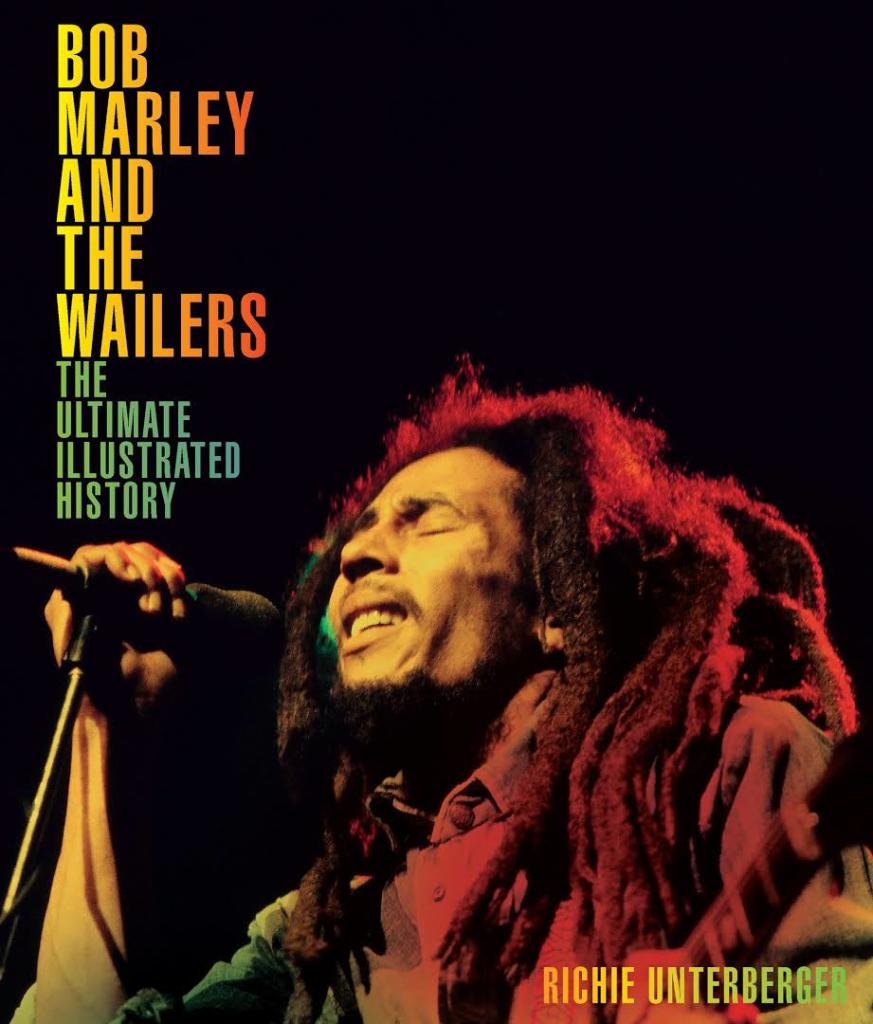

Blackwell was pretty quick to give the Wailers money to record an album, probably around early fall 1972. He’s gone over his meeting with the Wailers and decision to work with them in numerous interviews. Something that hasn’t come up much in Marley histories, however, is the extent to which the Wailers were known in the UK. The impression’s sometimes given that they were virtually unknown there (and everywhere else except Jamaica), with Island providing the gateway to an international audience. That’s basically true, but were they really unknown in the UK at the time?

If so, two perspectives that sometimes come up in Marley literature don’t compute. One concerns the breakup of their brief if productive relationship with producer Lee Perry in the early 1970s. The reasons for this were primarily financial, not artistic. They thought they had a deal to split royalties 50/50 with the producer, but according to Bunny Livingston, when it came time to dole out the money, Perry only offered ten percent. Straightforward enough, and ample reason to terminate the relationship if that’s how it went down.

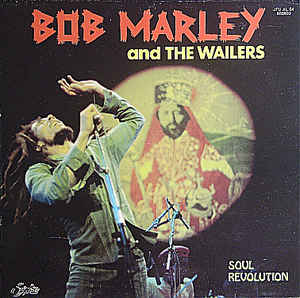

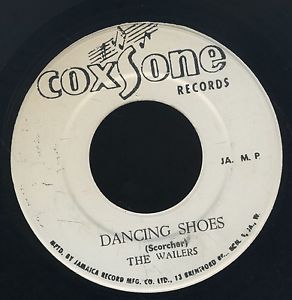

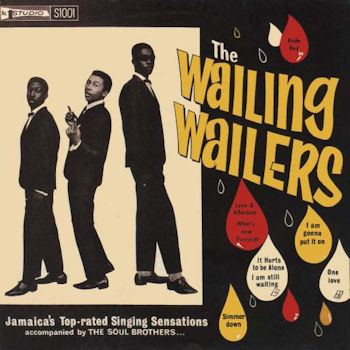

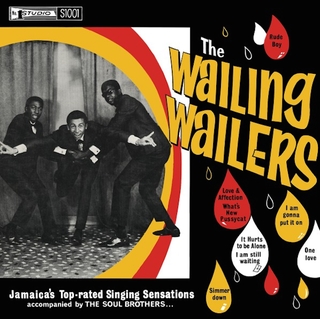

Some accounts, however, intimate that part of the reason they were angry at Perry is that the producer made good money they didn’t see by licensing Wailers material for UK release. There was quite a bit available for that purpose, Perry having produced two Wailers’ LPs in the early 1970s, as well as some singles (and an instrumental version of one of the albums, Soul Revolution). If the Wailers sold enough records to the UK market to make enough money to be worth fighting about, shouldn’t they have had an easier time arranging to do shows in Britain, and in summoning label interest before presenting themselves to Blackwell?

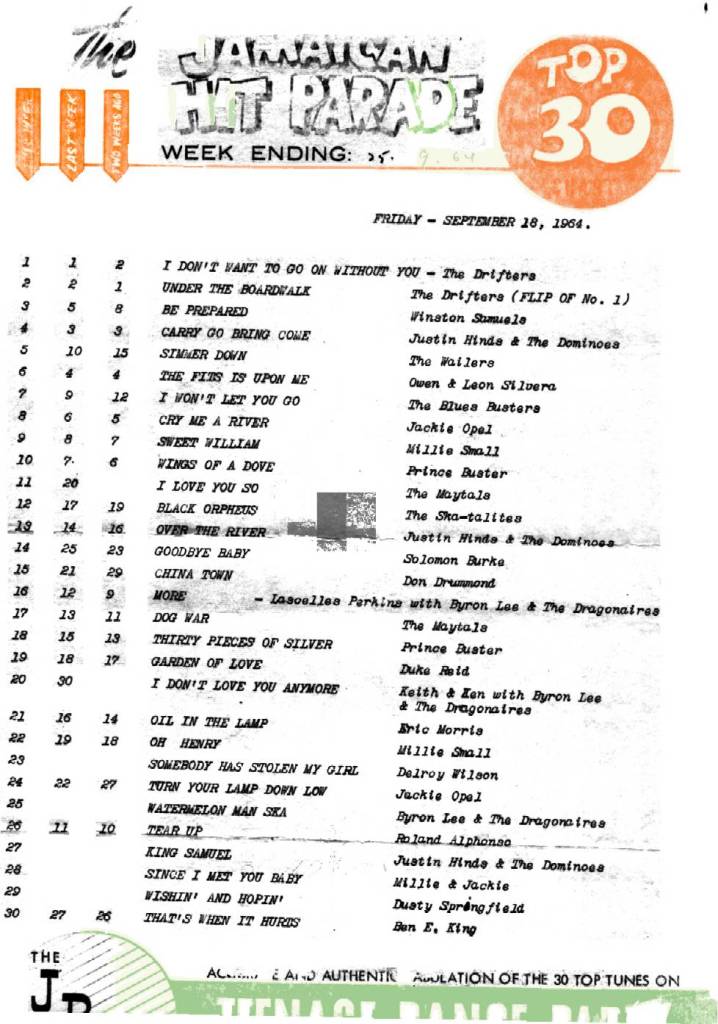

It’s also sometimes (and by no means universally) been reported that Coxsone Dodd, who produced the Wailers’ 1964-1966 recordings and released them on his own Studio One label, was sent quite a bit of money from sales of their product in the UK that he did not share with the Wailers. Indeed, it’s sometimes reported that the Wailers weren’t even aware of that money until quite a few years later. Again, if true, wouldn’t that indicate the Wailers would already have been known, at least to a modest degree, in the UK?

Chris Blackwell, when remembering how Island’s association with the Wailers began, gives the impression that he really wasn’t all that familiar with their work, in part because the rock side of Island took off so stratospherically in the late 1960s. Blackwell had gained a foothold in the record business by licensing ska for the sizable if niche market of Jamaicans in Britain, but branched into progressive rock in the late 1960s with the success of Traffic, Free, Jethro Tull, Fairport Convention, and others. It does ring true that he wouldn’t have kept up with reggae as avidly as he did back in the early-to-mid-1960s, though he did have one major reggae act, Jimmy Cliff (whose departure from Island was one reason he was keen to sign the Wailers). It seems like he might have known at least somewhat more about the Wailers than he let on, however, just like there are signs that Brian Epstein wasn’t really wholly unfamiliar with the Beatles when he first went to the Cavern to see them in late 1961.

Does it matter if there was some strange, nefarious reason the Wailers were flown over and did hardly any shows, or if they sold a good number of records in the UK before signing to Island, or if Blackwell was much more knowledgeable about the Wailers’ history and records than he’d later recall? Probably not. They did sign to Island, and Island did break them into the international market, though Tosh and Livingston started solo careers after a couple albums, before Bob Marley became a household name as the Wailers’ frontman. It would still be interesting to know the answers to these questions, however—as it would be for so many uncertain and peculiar aspects of the Wailers’ first decade.