This story was first posted on the KQED Arts website’s new series Into The Mix, which focuses on little-known stories from the Bay Area music scene’s past and present. Reproduced courtesy of KQED.

Hot tubs, water beds, sex, and drugs — all were staples of the Record Plant in Sausalito, home to some of the highest times of any Bay Area studio in the 1970s.

Yet there was no small amount of rock and roll too. The dozens of famous albums partially or fully recorded at the Plant in the ’70s include Sly Stone’s Fresh, Stevie Wonder’s Songs in the Key of Life and Prince’s debut album For You. The Plant continued its reign as one of the top studios in the Bay Area into the early 21st century, through several ownership changes that, at one point, saw the federal government running the facility.

That wasn’t the sort of atmosphere its founders had in mind when the Record Plant opened in late 1972. After establishing himself as a top recording engineer with the likes of Jimi Hendrix and Frank Zappa, Gary Kellgren opened successful branches of the Plant in New York and Los Angeles with business partner Chris Stone before the two set their sights on Sausalito. As Raechel Donahue (who coordinated KSAN’s live-in-the-studio concerts from the Plant) puts it, “They invented this idea of having a recording studio that gave everybody a comfortable place to be.”

The Record Plant in Sausalito, as it looked when photographed in November 2016.

“Basically, it was a party atmosphere to record in,” says Jim Gaines, who produced and engineered records by the likes of Santana, Journey and Huey Lewis at the Plant. “They built this studio up here to go for the Bay Area bands. But not only that, bring up people from L.A. that wanted to get out of L.A. They had a hot tub in it, they had a boat at one point in time [to] take people out. The house”— where members of bands like Fleetwood Mac would stay during their Plant sessions — “was part of the package deal. And Kellgren was a party kind of guy.”

Indeed, when Gaines interviewed with Kellgren for a job at the Plant, “I’m shaking hands with this guy in this purple or blue Napoleon outfit. He’s got the hat on and everything. I’m thinking, ‘Do I want to work for this guy? Good lord.’ It was all about a big party for him, as well as working. He seemed to put those two together. That’s why the studio was built.”

Gaines turned down the job in favor of staying at Wally Heider’s studio in downtown San Francisco, adding that “when Heider found out that they were coming into Sausalito, he went out and found a building. He had plans to build a studio in Mill Valley to counteract ‘em.” Notes engineer and producer Stephen Barncard, who, like Gaines, also worked sessions at both Heider’s and the Plant, “Wally had plans for a studio in Mill Valley near Tam Junction. I actually saw the plans. He was gonna get [TV and film production company] Filmways to pay for it, and when the Record Plant went in, it was over. It never happened.”

As just one example of the detail lavished upon the facility, recalls Gaines, “the ceiling in Studio B looked like clouds. They were made out of cut-out plywood in different forms, and covered with velveteen or velvet or something like that; they looked like clouds hanging up there. Kellgren was smart; he wanted his rooms to look different. He knew he wanted to make it artsy.”

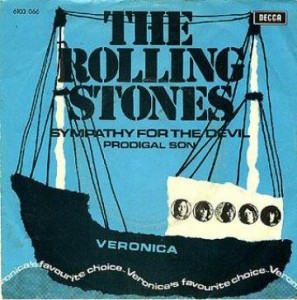

Word about the Record Plant got out through its lavish opening party, as well as KSAN broadcasts of live-in-the-studio programs featuring such heavyweights as Bob Marley & the Wailers (part of whose October 1973 performance at the Plant was issued on the Talkin’ Blues CD), Bonnie Raitt, Linda Ronstadt and Fleetwood Mac.

Part of this archival Bob Marley release features material recorded at the Plant in 1973 for a KSAN broadcast.

“At this time it wasn’t really common to do live broadcasts, especially from a recording studio,” explains Raechel Donahue. “When we were at KSAN, our version of a live broadcast was me and [DJ] Terry McGovern and a 100-foot microphone cord which I would feed out the window to him, so he could interview people on the street. It really was [KSAN manager] Tom [Donahue], Chris Stone, and Gary Kellgren who figured out, ‘Ah, there’s obviously a way to do this if we could only just figure this out.’”

KSAN kicked off its Record Plant broadcasts with a legendary 72-hour marathon. At one point during Kris Kristofferson’s performance, according to Raechel Donahue, “this wackadoodle guy came wandering through the studio singing ‘He’s a peach pit, he’s a pom pom, he’s a pervert, he’s a fool’” — bastardizing the lyric of one of Kristofferson’s most famous songs, “The Pilgrim, Chapter 33” — “and then just walked out the other door.”

“Everyone who was anyone was there, and they wandered in and wandered out,” Donahue said. “All I had to do was figure how to coordinate that. But that’s kind of what KSAN was all about, figuring out how to make reality blend into music. It was a crazy thing to do, but it did start the whole Record Plant live thing.”

It wasn’t the only craziness at KSAN broadcasts; Bob Simmons, the announcer for some of them, recalls Last Tango in Paris star Maria Schneider “wandering around trying to get someone to get in the hot tub with her” during one.

The Plant soon attracted not only stars from L.A. and out of state, but also quite a few from the Bay Area itself. The setting was as vital to its appeal as the studio itself. “Heider’s was downtown in the Tenderloin,” says Gaines. “That’s a whole different concept down there. I mean, just to park your car and get to the studio without being mugged is a feat. The Record Plant, you could just walk out, and you’re only like one door from the water. Then you got some public tennis courts down the streets. When I was working with KBC Band — Marty Balin and [Jack] Casady and Paul Kantner — Marty would go down there and play tennis while we weren’t working.”

The studio’s most famous feature, however, was on the premises, and more notorious for its, shall we say, extracurricular activities. The sunken area known as the Pit was, in Barncard’s words, “partial boudoir and studio. It’s basically for a place to do track-by-track overdubs and vocals, and then make love to your girlfriend between, in breaks over in the side.”

“Sly Stone moved into that back room for a while,” reports Gaines. “They had a little bedroom for him. Just a bed, with little frilly stuff over it. He wanted all of the doorknobs moved up. It’s like he was a kid or something. The doorknob couldn’t be in a regular place, it had to be like a foot higher. I finally changed that. I said, ‘Man, I can’t deal with this.’ There’s a lot more [stories], but I don’t know if I could tell some of ‘em.’”

Part 2

This story was first posted on the KQED Arts website’s new series Into The Mix, which focuses on little-known stories from the Bay Area music scene’s past and present. Reproduced courtesy of KQED.

After getting up and running in the early 1970s with some celebrity local musicians and KSAN broadcasts (see part one of this feature), the Record Plant in Sausalito seemed to be thriving in the last half of the decade. Steve Wonder, Fleetwood Mac, and Rick James all used the studio to record hits, and it’s where Prince cut his debut album. Yet there was no small amount of turbulence behind the scenes, culminating in the Plant almost getting shut down in the mid-1980s before reasserting itself as a top recording facility.

For all the glamour passing through its grounds, not everyone was enamored with the sounds. Although Fleetwood Mac did more than 3,000 hours of recording there for Rumours in early 1976, relatively little was used on the final album, which was largely recorded later that year in L.A. studios. Stevie Nicks may have used the privacy of the sunken area dubbed “the Pit” to write “Dreams,” though it was just as famous as a retreat for drug use by musicians and their visitors.

“The Pit was a complete idiotic idea,” says engineer/producer Stephen Barncard. “That’s how hard the studios were fighting to get those kind of clients.” While the drug use it fostered might have helped attract name players, as Barncard points out, it wasn’t always conducive to the best results. At one session he worked with short-lived semi-supergroup KGB (who included Mike Bloomfield, Carmine Appice, and Barry Goldberg), “Keith Richards was in the next room, and he was apparently passing around some kind of green snortable substance. [Producer Jim Price’s] friend who came along had snorted it up, and got really ill. That kind of put a pall over the whole session.”

As an engineer, Barncard is also critical of the space from some technical respects. “Even perfect equipment doesn’t necessarily always guarantee you’re gonna have a better record,” he feels. “I am really a fan of natural acoustics, of natural spaces. The Record Plant did not have natural spaces. It was the most unnatural. It was designed for totally isolated, multi-track recording, where you don’t have leakage between the tracks. Where you can go and punch in and fix things, and you won’t have anything behind there to give away the fact that you punched in there.

“Stevie Wonder, Songs In the Key of Life? That’s the deadest record ever recorded. That’s the Record Plant sound. I didn’t like to record there because I lacked time to make stuff sound decent, but I liked the people, the gear and the location,” Barncard continues. “Many, like [producer/engineer Jim] Gaines, were able to create hit records from there, and that’s all that counts in the end. But they had the gigantic budgets and my experience was a couple of overnight quickies and two weeks with New Riders of the Purple Sage, so take my opinion with a grain of salt. In the end, we’re talking different styles of producing, and it’s all good.”

Projects continued to roll into the Plant in the late 1970s and early 1980s, but the studio’s ownership was in flux, soon threatening its very existence. Co-founder Gary Kellgren, the engineer/producer who was the artistic force behind the operation, drowned in his Hollywood swimming pool in 1977. In the early ’80s the other co-founder, Chris Stone, sold the Plant to a quadriplegic teenage music fan, Laurie Necochea. In 1984, a year before her death, it was sold to Stanley Jacox.

Around that time, the Pit was rejigged for more constructive purposes. “While I was doing the Con Funk Shun record [‘Electric Lady’], John Fogerty calls me,” Gaines said. “He’s coming out of retirement, quote-unquote, and he wants a studio. I had just opened up [the former Pit as] the little C room in the back. He said ‘Jim, I’m just gonna do this record myself. I’m playing all the instruments. Can you engineer it?’ I said, ‘Well, I’m in the middle of a record, I’ll give you my assistant Jeffrey Norman. Just move into the back. We need to open up the room anyway, and you’ll be easy.’

“When we turned it back into a real studio, Centerfield was the first record cut in that little room. There would be days when I had Starship in one room, Huey Lewis in another room, and Fogerty in the other.”

Yet soon after that, Jacox was accused of manufacturing amphetamines in his home and investing some of the proceeds in the Plant — and the studio was actually taken over by the federal government.

“The day the studio was shut down, I had a session with Journey,” remembers Gaines. “I noticed there’s a lot of cars in the parking lot for 9:30. As I’m approaching the door, here comes federal marshals; all kind of police are surrounding me. They said, ‘We’ve just taken possession of the studio, and we need to interview you.’

“They went through the studio, looking for drugs. They thought that was the source of the ‘drug manufacturing,’ quote unquote,” Gaines says. “They didn’t find any drugs. I mean, there might have been a joint or something in one of the road cases, but they were highly disappointed.

“They basically told me, ‘Look, we’re gonna take possession.’ Fortunately, I had Journey in there with all their gear and stuff. I said, ‘Well, you can’t take possession until I get all my band’s gear out of here, and tapes. ‘Cause we’re working on a record, and you cannot have any of this stuff. It doesn’t belong to the studio.’ I called the band up and said, ‘We gotta clear outta here. Everybody come and get stuff.’

“It was shut down for around six months or so, maybe more. At one point, the federal marshals offered me a position to open and run the studio. I said to them, ‘Look, if my clients knew I worked for the federal marshals, you think that they would come in here? Here’s the deal. Take my secretary, make her the studio manager, and I will come in and do some work.’ I actually opened the studio with Santana when that part reopened.”

Gaines was also working with Santana at the studio for the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.

“Carlos and one of his main guys had just left to go shopping when that quake hit. I was working with Chester Thompson doing some organ overdubs. We were in studio A; I didn’t think we were gonna get out of there before that damned thing came down. When it hit, you can feel there’s some low-end rumble or something going down. So CT looks at me and says, ‘What the hell are you doing?’ I said, ‘What are you doing?” And we both said, ‘Uh-oh.’

“And we hit flying into that door, man. We’re out on the ground out in the parking lot, and the ground is rolling along. I had a bottle in my car; we sit in the parking lot, found us some cups, and turned the radio on, listening to ‘Bay Bridge collapsing and the freeway collapsing.’ One of the consoles got beat up pretty bad, and twisted a little bit. We was down for about at least three or four days. Phones didn’t work. The only thing that worked was the fax machine, for some reason. We never figured that out.”

Part 3

This story was first posted on the KQED Arts website’s new series Into The Mix, which focuses on little-known stories from the Bay Area music scene’s past and present. Reproduced courtesy of KQED.

When Arne Frager took over the Plant in Sausalito in 1988, he wasn’t much interested in sex, drugs, and rock and roll.

“I was really interested in rebuilding the studio into a really great sound emporium for making records,” Frager said.

If hits are what a studio’s judged by, it generated plenty of those over the next decade and a half or so. It held sessions for big albums by Carlos Santana, Metallica, Dave Matthews, John Lee Hooker, and Mariah Carey, as well as for lesser-selling but celebrated artists like the Kronos Quartet.

A doorway to the Plant, as it looked in November 2016.

“It was a party studio throughout the ’70s, until the government seized it in 1985,” says Frager, as the first two parts of this series illustrate. “I had Herbie Herbert, the manager of Journey, tell me he’d never go there, even though he knew I was rebuilding it and was more serious about business. He said, ‘I tried to talk Journey out of going there, and they went there and wasted lots of money just partying. I didn’t like that.’”

So if the partying, if not eliminated, was no longer as much the focus, what was drawing so many acts to the Plant, both from the Bay Area and beyond?

“You would have the ability to step outside and be surrounded by these gorgeous, tall eucalyptus trees, and walk a few steps out to a beautiful dock by the edge of the bay,” remarks producer/engineer Enrique Gonzalez Müller (now also a professor at Boston’s Berklee College of Music), who was on the staff for several years starting in 1999, and continued to work on Plant projects until its 2008 closure. “But at the same time, you didn’t really feel the need to step out of the studio because the vibe was amazing!

“One of the studios that had a lot of use, called the Garden—which used to be Sly Stone’s personal room back in the day—the lounge for that studio was literally outside, in the open air. The lounge was this beautiful little garden that had fish in a pond and a Jacuzzi that you could relax in. It wasn’t really the type of atmosphere that you find in a lot of big studios where you do want to step out for air and escape the pressure of making records. People just relaxed, hung out, and that level of ease and comfort definitely transpired onto the music being captured within those walls.”

Just because Frager was the owner didn’t mean he always got special treatment. When Van Morrison was booked for an album, “the only words he spoke to me in the month he was at the Plant were ‘Hi, I’m Van’” as Arne was waiting to greet Van the Man at the studio’s front door on the first day of the sessions. When Frager went to Studio C to introduce himself to Starship, their manager “blocked the door and said ‘hey, you can’t come in here,’ and locked the door in front of me.” When Stephan Jenkins from Third Eye Blind kept parking his motorcycle in Arne’s space by the front door, according to Frager, Metallica bassist Jason Newsted relieved himself on the vehicle in rebuttal, though by the time Jenkins came out at night hours later, the stink had evaporated.

Such hijinks, however, seemed to take a back seat to more serious work, such as sessions Gonzalez Müller worked on for the Kronos Quartet’s You’ve Stolen My Heart. “Kronos decided that they were going to record and re-create every single element heard in these [vintage] Bollywood scores, which have gigantic orchestral, super-quirky, unconventional instruments,” he recalls. “We needed to do a ton of overdubs. If they wanted to record one melody, they would record it three, six, eight times to create the sound of a larger orchestra. It became this beautiful monster for us engineers. We had to be on top of this massive amount of musical input that then we had to filter, sift through, and condense into something palatable.

“They brought in Asha Bhosle,” the Indian singer on the original recordings of this material, composed by her late husband, R.D. Burman. Then in her early seventies, “Asha had more energy than any of us, and the Kronos Quartet are an energetic bunch. When she started singing, it was an exact photocopy of what you had heard her do in the ’50s. Every single peak and valley of her vibrato seemed to be performed perfectly, deliberately, and assertively.

“Here we were in a laboratory making this beautifully layered, complex Persian rug one little tedious hair at a time. I might be misquoting the year, but to paraphrase, she shared this anecdote: ‘In 1943, I had to do two albums in one day. I remember reading the score as a young singer, and it had instructions for when to ‘duck,’ because the entire orchestra was recorded with one single microphone, live!’ The flutes were behind her, and if she didn’t duck, the microphone couldn’t capture their fragile sound accurately. That was such a profound story for me for how there’s a million ways that you can capture emotionally captivating music.”

While Frager takes great pride in hits like Santana’s Supernatural (where a Polygram executive who signed Carlos came to sessions for a couple weeks just to hang out because he was such a big fan of the guitarist), he’d also sometimes let up-and-coming bands use the facilities. “We did a band on spec, just to help them, called the Monophonics,” who are from San Francisco and are “kind of a funky horn band. They’re out there touring all over the world doing really well. We gave ‘em the time at the Plant just for their first record. No charge.

“I always felt it was a crime to see a studio with a million-dollar investment, or 2 million, sitting there empty. If people approached me, and had a project—sometimes I had an interest in the project—sometimes we just gave ‘em the studio,” though he acknowledges he also did so for “a long list of bands nobody’s ever heard of.” 4 Non Blondes’ 1993 hit “What’s Up” was also cut at the Plant. But as Arne notes, singer-guitarist-songwriter Linda Perry never brought “another dollar’s worth of business into the Plant” after leaving the band for a solo career.

Frager sold the studio in 2008, although it kept running for another month or two. Since then the Plant in Sausalito has ceased operations, though the building’s now being used by Harmonia, “a health and well-being social club” (as its website describes it).

“We started losing money in 2000 because of Napster,” says Frager. “Young people who used to buy records suddenly found out that you could get music for free. I kept it alive for eight more years with my own money. I put [in] over $1 million, thinking ‘this can’t possibly stay this way. These record companies are gonna figure this out.’ I ran out of the ability to use my own personal funds. By the end of 2007, I could no longer afford to keep the doors open. Nobody’s making any records there, and that’s really what that building is for. They’ve been trying to sell it ever since I closed the doors.”

While Frager has moved on to a new chapter in his life and is now “signing and developing unknown artists,” he maintains the Plant Recordings Studios site “because that’s my brand. Above any studio I’ve ever been in that was a major studio, this place kind of had a laid back, relaxed feel. It was very conducive to making records. I always felt there was magic in that building. I still do.”

For Sale sign for the building formerly housing The Record Plant in Sausalito, November 2016.