Baseball season’s starting, and with it the unavoidable hopeful predictions that so-and-so is poised to have a “breakout” year. Much of this is hype from managers, owners, broadcasters, and sometimes the players themselves. Every year sees some “career” years that are unexpected, but you can’t count on too many of them, no matter which team you’re following. Here on the San Francisco Giants, for instance, it doesn’t seem impossible that Brandon Belt would somehow put it all together one year and hit .330 with 35 homers and 120 walks. Even if he did, however, it’s likely that would be his one “peak” year, and he’d revert to his usual streaky slightly-above-average performance at the plate.

Some years do see more out-of-context performances than others. I don’t know if there’s any way to measure such things, but for some reason, 1970 seemed to see more of them than most other seasons, and perhaps any other season. You could field a killer All-Star caliber team with the guys who, for just that year, exceeded their career norms by implausibly high margins.

Perhaps the most improbable of them, given his age (33) and how he’d never before approached stardom in his nearly decade-long career, was Cubs outfielder Jim Hickman. His career high in homers had been 21, his highest batting average .257. He’d even been demoted to the minors for a while a couple of years previously, at the age of 31. Suddenly he was a Triple Crown threat, hitting .315 with 32 home runs, 115 RBI, and 93 walks. He even delivered the game-winning hit in the bottom of the twelfth inning of the All-Star game—the famous one in which Pete Rose scored the winning run by crashing into (and injuring) catcher Ray Fosse. Hickman had a couple of fair years for the Cubs over the next two seasons, but never approached those numbers again.

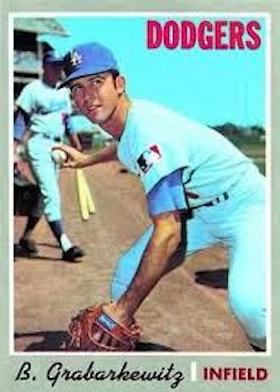

On base between Hickman and Rose as that All-Star finish played out was Billy Grabarkewitz, who that year hit .289 with 17 HR, 84 RBI, 95 walks, and 19 stolen bases for the Dodgers—the only season, unbelievably, in which he had more than 200 at-bats. Grabarkewitz had hit a mere .092—that’s not a misprint—in 65 at-bats the previous year, in his first big-league trial. Injuries would limit his playing time to 90 at-bats in 1971; he his a woeful .167 with more action (144 at-bats) in 1972; and he never got regular playing time again. What happened?

“What was amazing was the day after the All-Star game, which was a day off, [Dodgers general manager] Al Campanis calls me into his office and says, ‘You’re doing real good, but you know you need to cut down on your strikeouts,’” Grabarkewitz told Michael Fedo in the book One Shining Season. “So he got [coach] Dixie Walker to go out and work with me. I’m hitting .376 and Dixie wants to change my whole hitting style again. And he says, ‘First of all, you need to quit swinging for home runs.’ He switched me to a heavier bat again, and it’s like I didn’t have a choice. I’m being told to do this. So in the month of August, I don’t think I struck out six times. And I think I hit .101…[in September] I went to [the lighter] bat, and the last month I did real good again—hit home runs, struck out a lot, but got base hits.”

For the record, Grabarkewitz was actually batting .341 at the All-Star break; he’d have two walks and a two-run homer, his tenth, the first day after the break. But he was indeed down to .289 (and had been dropped from leadoff to the eighth spot in the order) by the end of August, in which he batted .173 (not .101, but bad enough). (He also struck out 26 times in August, not six.)

What really killed his career, however, might have been (again according to his memory in One Shining Season) being told to work on double plays for a long time the second or third day of spring training the following year. That hurt his shoulder badly enough to keep him out of the lineup most of 1971, and he never got a foothold in the big leagues again, with the Dodgers or several other team he’d play for over the next few years.

Or, there might have been a more prosaic explanation. I wish I could find it for reference, but I remember Phillies broadcaster (and ex-center fielder) Richie Ashburn writing in a newspaper column that Grabarkewitz had come looking for him after a game because of a negative comment from Ashburn. Ashburn wrote something along the lines of that if Grabarkewitz had tried to hit him, if Ashburn had curved, Billy would have missed.

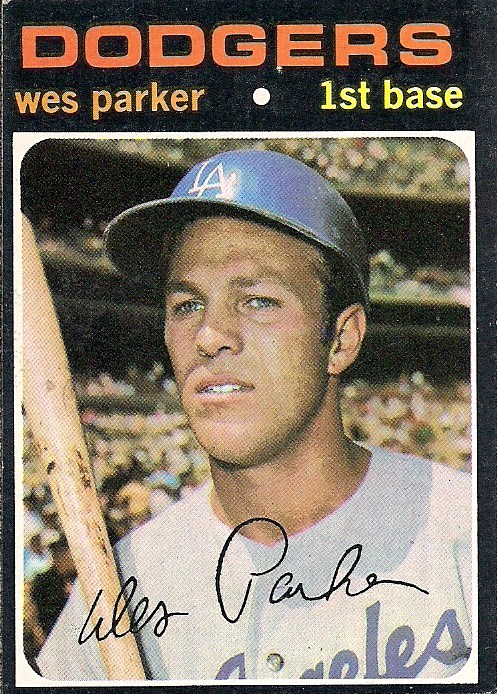

Also on the Dodgers that year, in the midst of a much longer career, was Wes Parker, regular first baseman for the team since the mid-1960s, including on the pennant-winning squads of 1965 and 1966. Although acknowledged as an excellent fielder, Parker had never seemed to live up to his potential at the plate. His best season had been 1969, when he hit .278 with 13 homers (though just one came after July, around the time he had an emergency appendectomy). In 1970, however, he had his only superb year, hitting .319 with 111 RBIs, and leading the league with 47 doubles.

His explanation for why he didn’t approach those figures again will no doubt vex Dodgers fans unaware of Parker’s attitude at the time. “After doing that for one season, I decided it wasn’t worth it,” he revealed in One Shining Season. “It was a conscious decision on my part that the sacrifices and effort, the amount of energy that had to go into it, was more than I thought it warranted. 1970 was for one season only. I’m glad I did that once, but I wanted to enjoy all aspects of my career, part of which was dating again, part of which was enjoying people. I didn’t want to live like a hermit again”—which he’d done in 1970, so he could focus almost exclusively on baseball—”and I really believe that’s what it would have taken for me to have another year like 1970.”

There could have been other grounds for criticizing Parker’s approach to the game. Again I wish I could find the newspaper story, but I remember in 1976, Phillies manager Danny Ozark (who’d been a coach with the Dodgers in 1970) was getting on outfielder Jay Johnstone for not hustling on extra-base hits that could have been triples, stopping at second to pad his doubles total. (Johnstone hit 38 doubles that year, finishing second in the National League.) Parker, Ozark remembered, had led the league in doubles back in 1970 by doing the same thing.

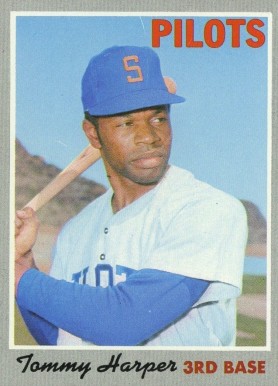

Moving across the diamond, at third base Tommy Harper had a superstar year for the Milwaukee Brewers, then playing their first year under that name after having started life as the Seattle Pilots in 1969. Harper always had speed—he’d stolen 73 bases the previous year—and he’d flashed some power by hitting 18 homers for the Reds in 1965, though he’d never hit more than ten in any other season. Suddenly he hit 31 homers to go with 38 stolen bases, a .296 average, 35 doubles, and 104 runs. He’d never come too close to that stat line again, and never hit more than 17 homers in his remaining years, though he did lead the American league with 54 stolen bases in 1973.

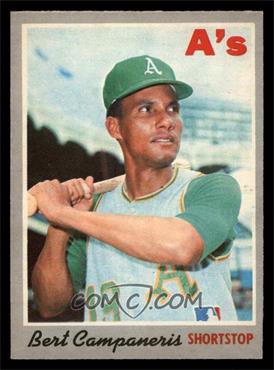

At shortstop, Bert Campaneris had the best career of any player to have a fluke season in 1970. He made the All-Star team six times; led the American league in stolen bases six times; and was the shortstop on the A’s team that won three straight World Series in 1972-74. He was not, however, a power hitter, with 79 home runs in a 19-year career. Except, that is, in 1970, when he somehow clubbed 22 roundtrippers (and 28 doubles). In no other year did Campaneris manage more than eight homers. In 1969, he hit two; in 1971, five.

There’s no vintage anecdote explaining what happened, but it’s interesting to note that Campaneris turned on the power again for a few weeks a few years later, when it mattered most. In 1973, he hit just four home runs (and slugged just .318) in the regular season. Yet in the postseason, he hit three—two in the American League playoffs, and one in the World Series.

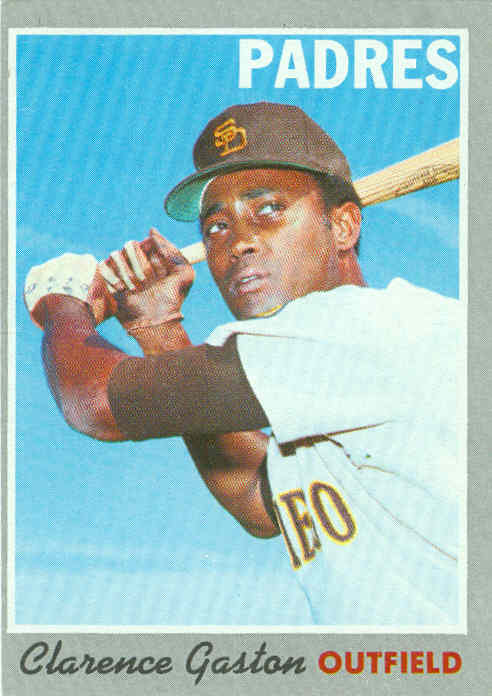

In San Diego, Cito Gaston, like Jim Hickman, had a near Triple Crown-worthy season — .318 average, 29 homers, 93 RBI. It was all the more shocking coming after a rookie year in which he’d hit .230 with two homers, slugging .309. Unlike Hickman, Gaston was relatively young (26), and fans of the second-year-expansion Padres entertained reasonable hopes they had their first superstar. Yet the following year, his average dipped to .228, with 17 homers. Only once did he top ten homers again, with 16 in 1973, his last year as a regular.

As great as his 1970 was, Gaston never did master the strike zone. Even in ‘70, he struck out 142 times—the same year he had his highest walk total, a modest 41. His 121 whiffs in 1971 (accompanied by a mere 24 walks) suggests poor command of the strike zone that pitchers learned to exploit. Gaston’s greatest fame, of course, came not as a player, but as a manager with the Toronto Blue Jays in 1989-1997 and 2008-2010, where he was the first African-American manager to win a World Series (in both 1992 and 1993).

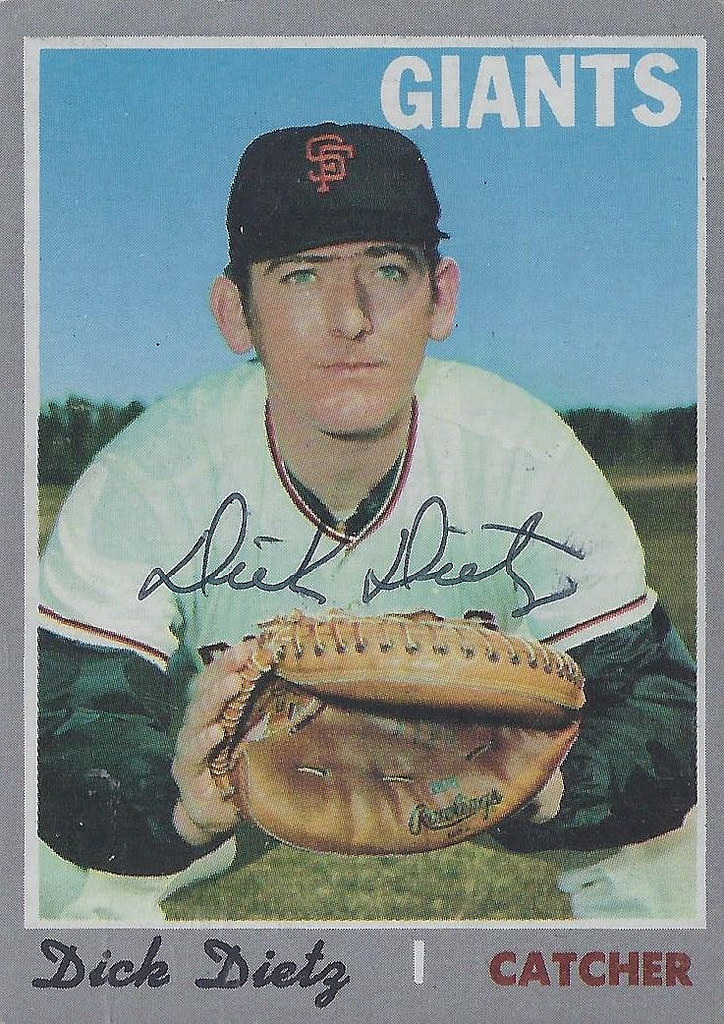

Behind the plate, San Francisco Giants catcher Dick Dietz had an amazing 1970, at least at the plate. He hit .300 with 22 HR, 107 RBI, and 109 walks, not to mention 38 doubles. He’d only played semi-regularly in his earlier seasons, but for that year, was almost as good a hitter as the National League MVP, fellow catcher and future Hall of Famer Johnny Bench.

Dietz tailed off in 1971, but was still very above average for a catcher as a hitter, with 19 homers and 79 walks. Somehow he was waived (not traded) to the Dodgers in April 1972, where a broken hand ruined his 1972 season, in which he hit .161 in 56 at-bats. He rebounded with a rather phenomenal, if unheralded, year as a reserve (playing more first base than catcher) for the Braves in 1973, hitting .295 and walking 49 times in just 139 at-bats, compiling a .474 OBP. That translates to about 150 walks in a full-time year.

Dietz was just 31, and it seems like he should have kept finding work as a reserve, perhaps moving to the American League to DH considering his subpar defensive reputation. It’s been suggested that he was blackballed owing to his role in the 1972 players strike, when he was serving as the Giants’ player representative (and, likewise, suggested he was waived to the Dodgers in early 1972 because of that as well).

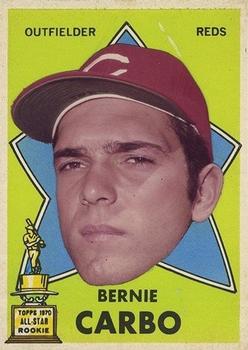

With a bit of juggling, you have a starting eight of fluke 1970 seasons here. You could move either Grabarkewitz or Harper from third to second (both played some second base in their career). There are only two outfielders; you could add Bernie Carbo, who had a great rookie year as a platoon player for the Reds (21 HR, .310, 94 walks in just 365 at-bats) and never hit nearly as well again.

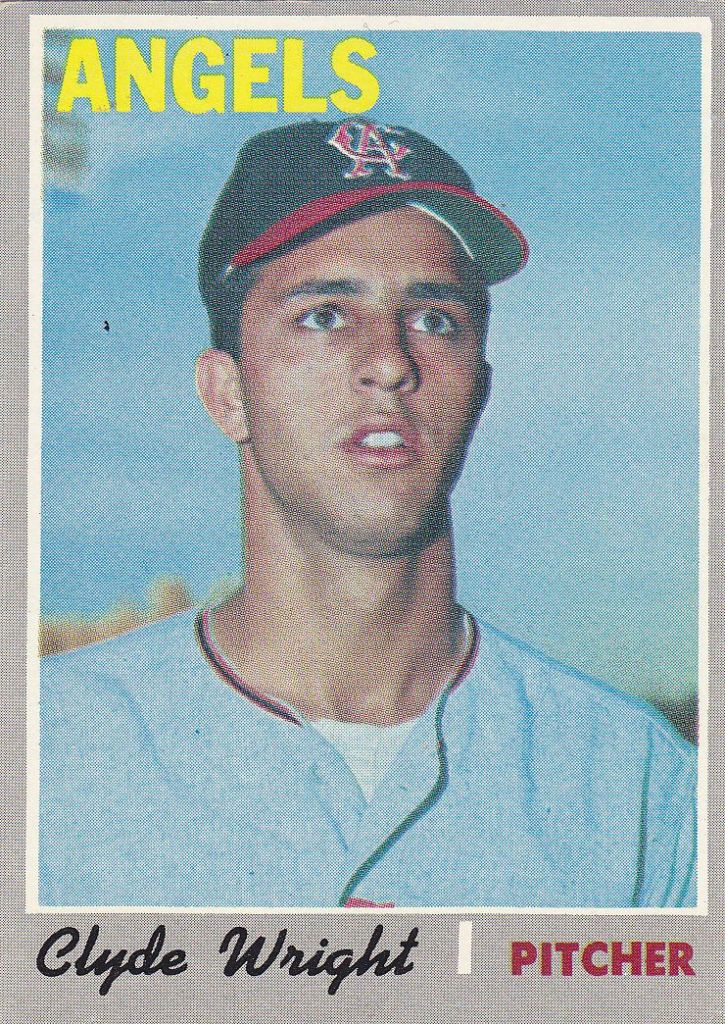

Pitchers aren’t nearly as well represented by fluke 1970s, but there was one guy whose All-Star year came out of nowhere. Clyde Wright had started and relieved for the Angels for a few years without distinction, especially in 1969, when he was 1-8 with a 4.10 ERA. In 1970, he somehow won a place in the rotation and rocketed from 1-8 to 22-12. He’d have a couple other good years in 1971 and 1972 (winning 34 games with a sub-3.00 ERA) before declining into retirement by the mid-’70s. His 12-6 record at the break was good enough to get him a spot on the American League All-Star squad, where he gave up the game-winning hit in the twelfth inning to…Jim Hickman, which is where we started.