Because I’m known mostly as a music journalist, it surprises some people that when I travel, I spend most of my time doing non-music-related things. I have a lot of interests besides music, and since writing and teaching music history takes up a good part of my professional life, it’s good to get away from that for a while. When I did two days of presentations this fall at Colorado College, I took advantage of the opportunity to make it a ten-day trip to Colorado, most of which I expected to be full of the non-musical activities the state offers.

Still, I’d not been in the state 24 hours before a music site appeared unbidden. One of the first things I did after arriving in Denver was go with a friend to Red Rocks Amphitheater. That wasn’t so much to see the amphitheater—which has staged countless concerts by big names, going back to a Beatles show in 1964—as to take in the actual red rocks of the surrounding area. I had no idea that the visitor’s center houses a Colorado Music Hall of Fame, which I ended up touring within minutes of arrival.

Colorado is known for several things—the Rockies (both the mountains and the baseball team), skiing, and as the training grounds for many Olympic athletes. It’s not especially known for music. The star most strongly associated with the state is often derided for his sentimental pop-folk-country. But one of Colorado’s top tourist attractions has decided to celebrate its musical heritage in its portal. And there’s no admission fee, so why not check it out?

Those wags who figure there’d be little to show in a Colorado Music Hall of Fame besides a John Denver wing might feel validated by the biggest room in the display, devoted solely to the “Rocky Mountain High” man. But the hall — really more a moderate-size floor — does take up the equivalent of three or four fairly big rooms, with plenty of photos and text on the display panels. Sure, it’s stretching it to feature musicians who spent some early time in the state but made their big impact elsewhere, like early jazz stars Paul Whiteman and Glenn Miller. Yet there should be material here of interest to anyone with a fairly wide knowledge of popular music, even if little emerges of a style or styles particularly indigenous to Colorado.

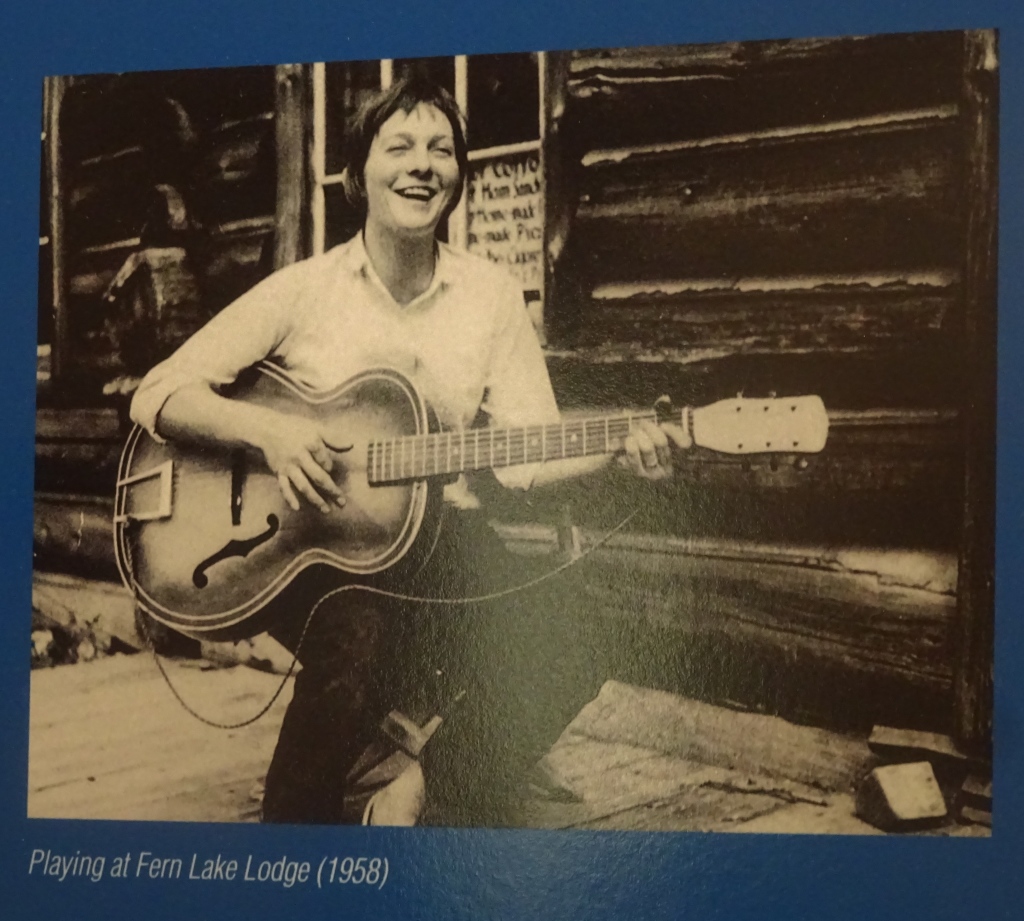

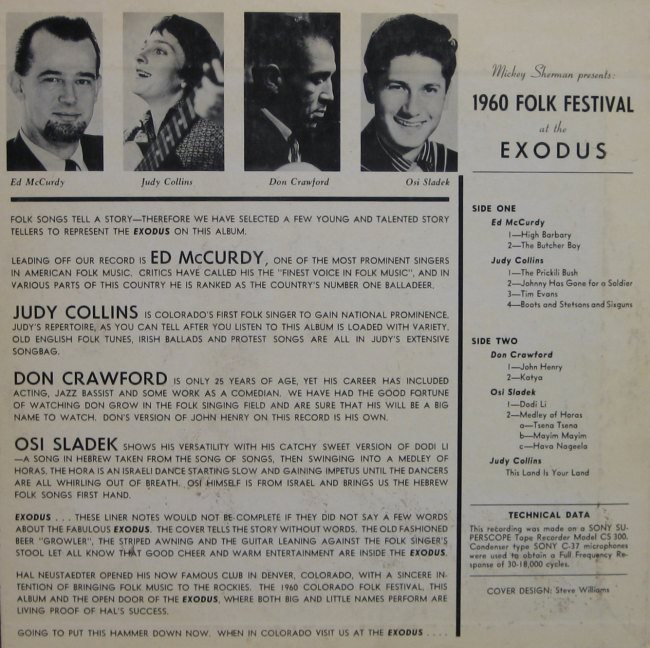

Denver isn’t particularly known as a folk music nexus, but it had one of the more active scenes in the late-’50s/early-’60s folk revival, particularly at the Exodus club. By far the biggest performer to emerge from that scene—even if she, in common with many other artists spotlighted here, was based elsewhere for most of her career—was Judy Collins. Before signing to Elektra Records, the label she spent many years with as a folk and then pop star, she even had a few tracks on a couple rare local compilation albums, 1959’s Folk Festival at the Exodus and the following year’s similarly titled 1960 Folk Festival at the Exodus:

Before signing to Elektra Records and doing her first album, Judy Collins had a few tracks on this rare local LP.

These albums have never been reissued, to my knowledge, and you can’t even hear them online. They’re pretty rare; other than at this hall’s displays, I’ve only seen a copy of one of them once (in a private collection, not in a store). Anyone with leads to hearing these cuts should feel free to contact me.

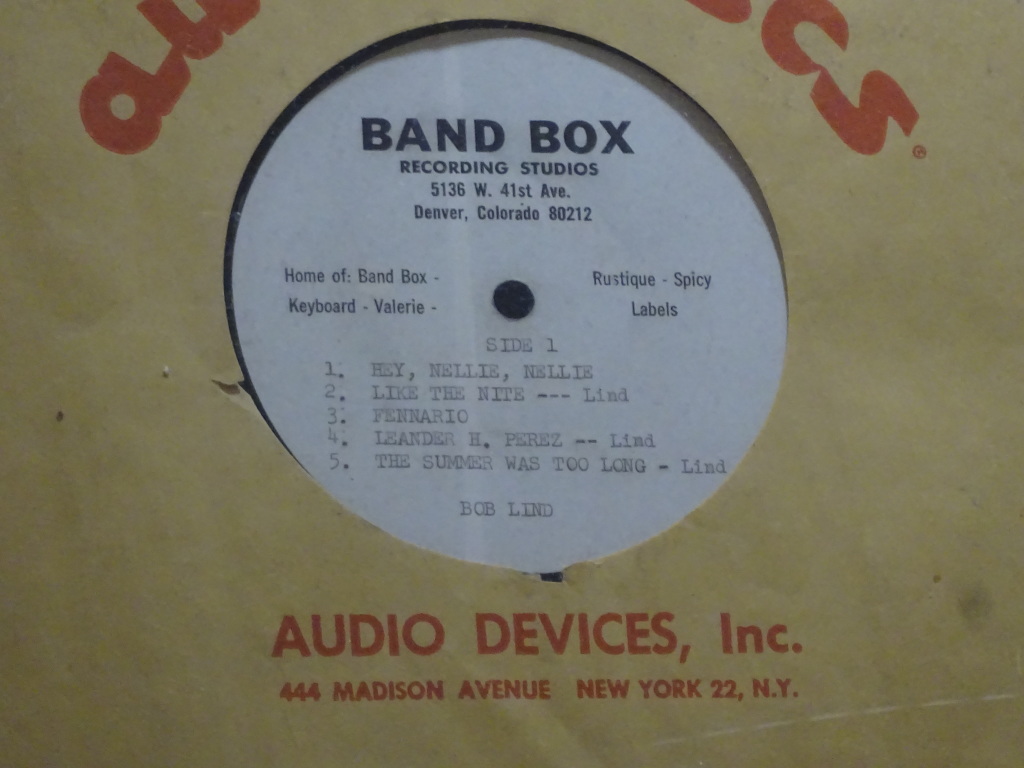

While the folk section takes up a few panels, much of that space honors the Serendipity Singers, one of numerous wholer-than-wholesome folk revival combos. Another area has some info on Bob Lind, who was a ’60s Colorado folkie before moving to Los Angeles and recording the early folk-rock hit “Elusive Butterfly.” I’d like to hear this demo that was on display, which has a couple songs from his 1966 LP The Elusive Bob Lind (which has acoustic performances overdubbed with additional instrumentation without his consent), but some others which aren’t on that album:

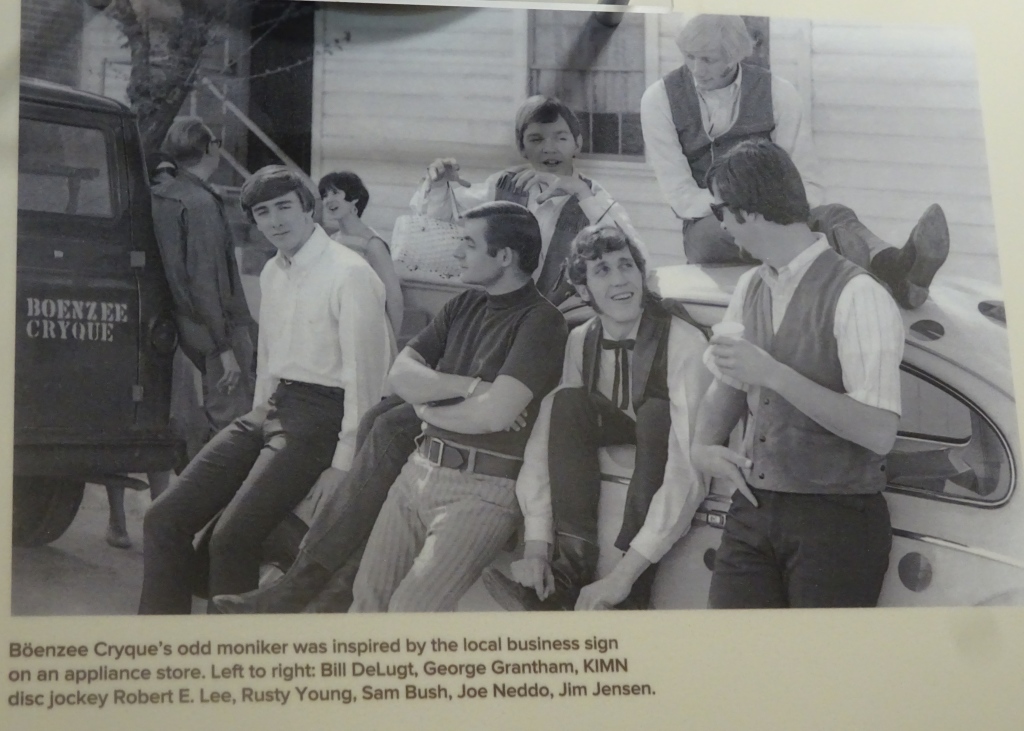

Some musicians started their professional, and sometimes recording, careers in Colorado before reaching stardom in the 1960s and 1970s. Some of them don’t interest me much or at all, but some of them would go on to one of the best country-rock bands (at least on their first LP), Poco. Here’s a picture with a couple future Poco guys, George Grantham and Rusty Young, in the oddly named Boenzee Cryque:

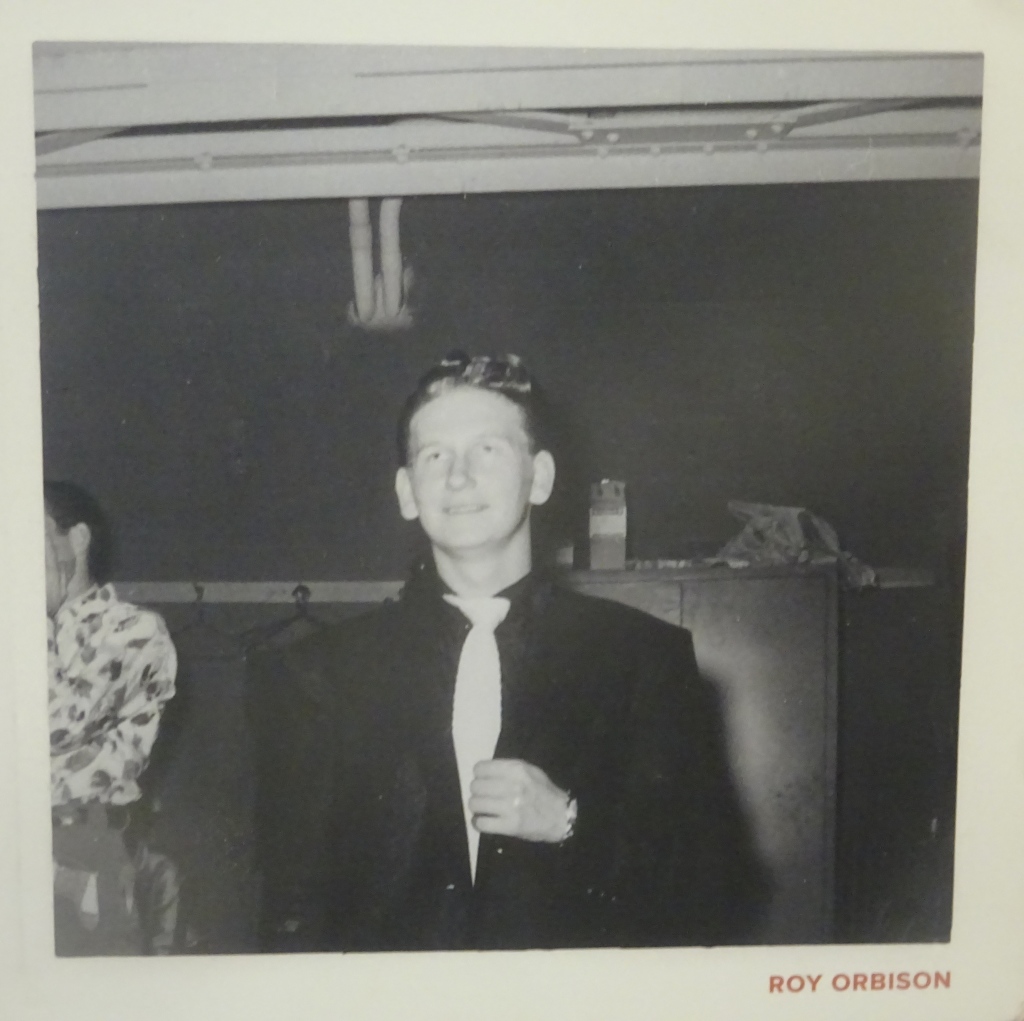

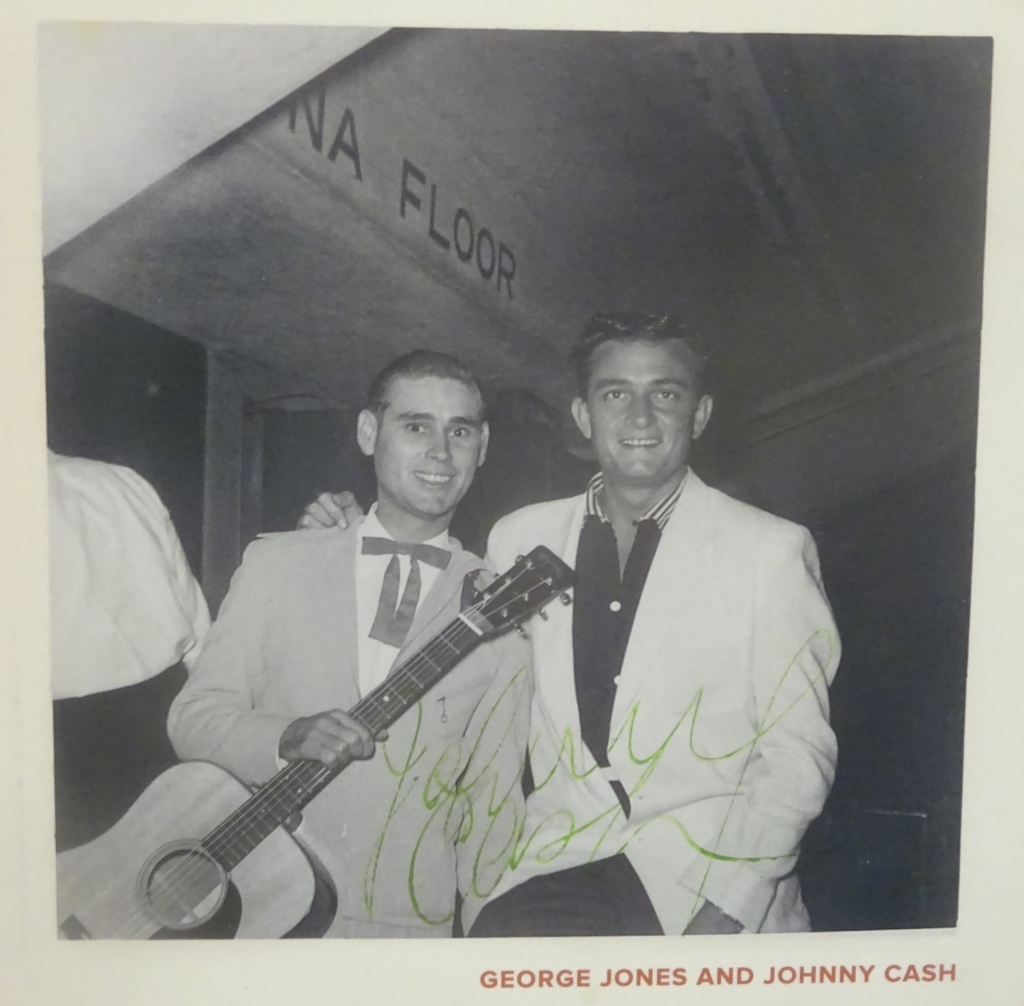

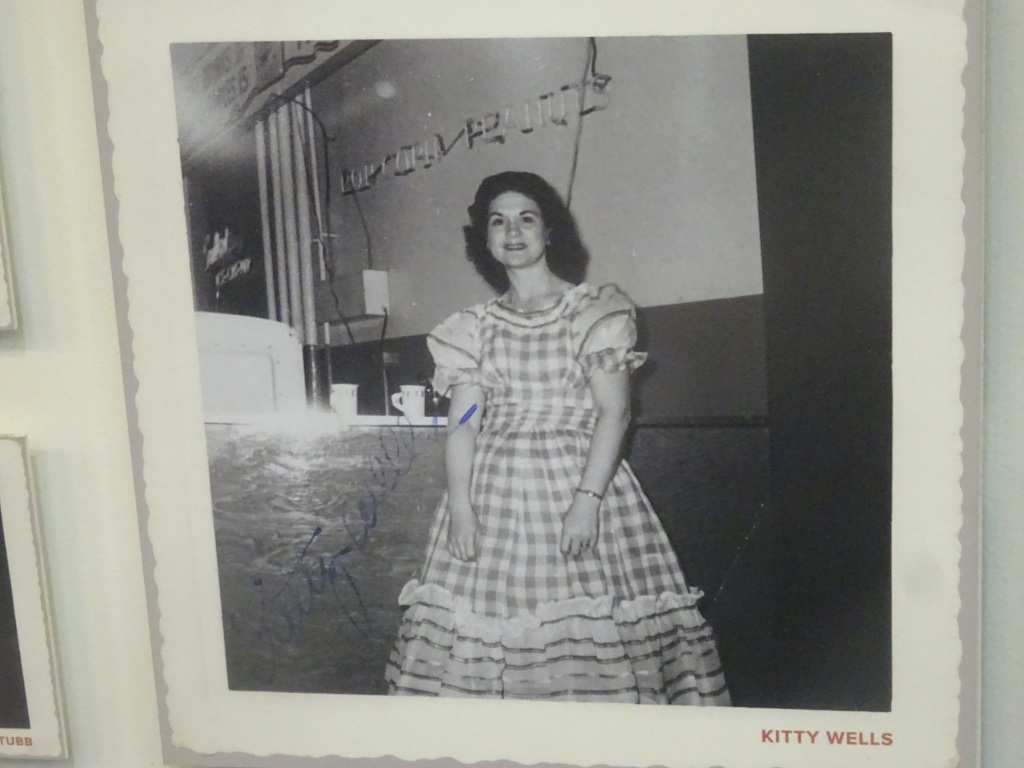

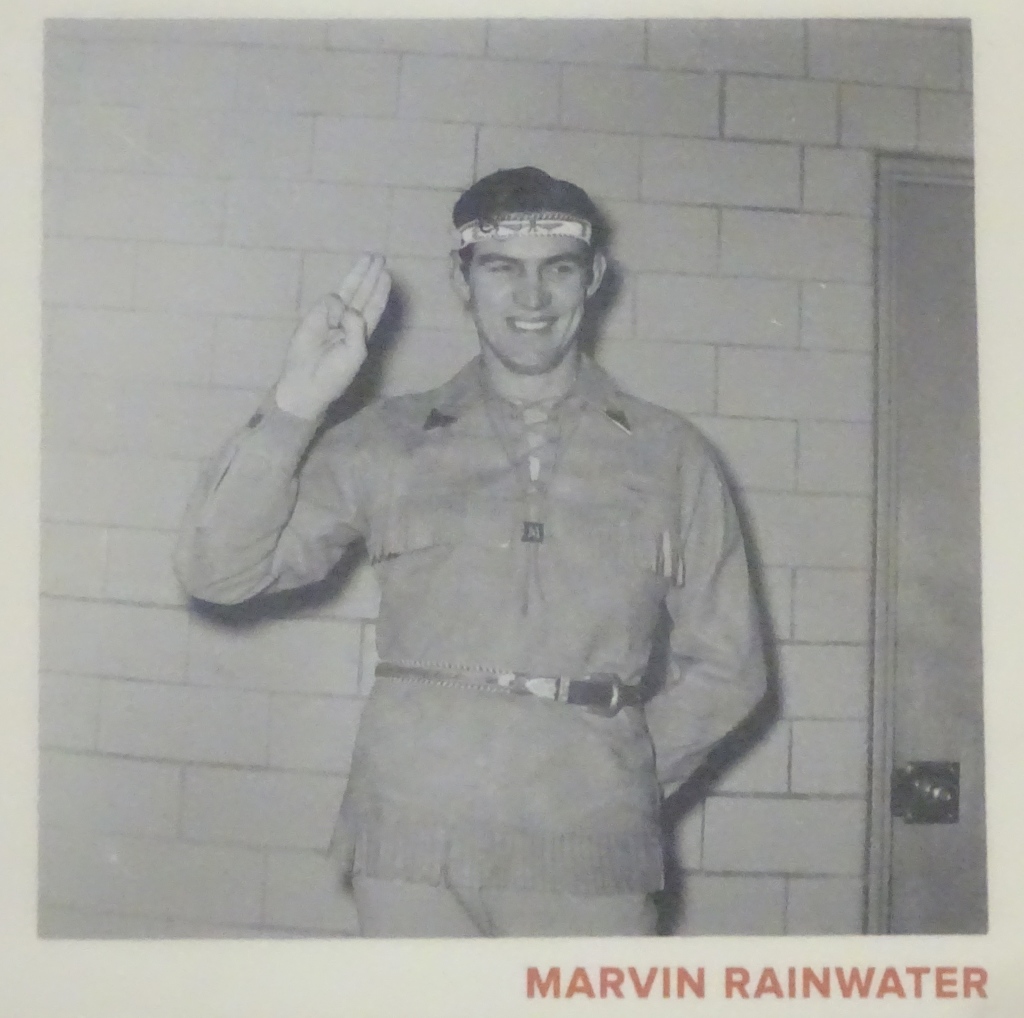

Yet the most interesting part of the hall features performers with no strong Colorado connections, other than having performed there. In the mid-1950s, George Kealiher, Jr. photographed numerous country and early rockabilly stars at the Denver Coliseum, and literally dozens of his pictures are featured on one wall. I’d never seen any of these before, and they’re not all of big stars, as the one of Marvin Rainwater demonstrates:

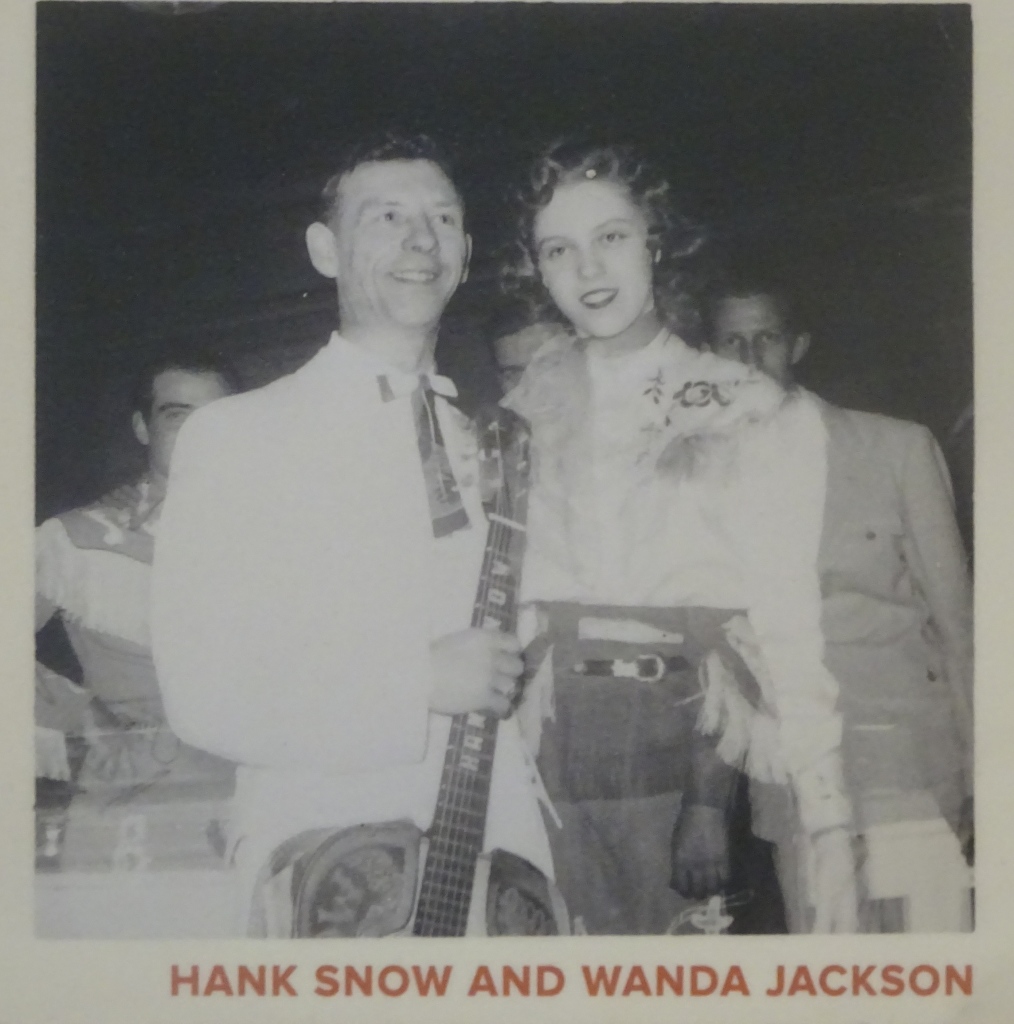

A mistake seems to have been made, however, with this caption:

I’m a pretty big Wanda Jackson fan, and that sure doesn’t look like her to me. A-B it with this early Jackson picture:

Colorado wasn’t especially known as a hotbed of ’60s and early ’70s rock. But one room makes the most of what happened there, with a panel on the Astronauts, a surf group (yes, a surf group in landlocked Colorado) who were enormous in the region and had some modest national success. There’s also an enormous family tree—far bigger than you’d suspect could be possible—for Sugarloaf, who made #3 in 1970 with “Green-Eyed Lady” (and the Top Ten in 1974 with the obnoxious “Don’t Call Us, We’ll Call You”).

More significant, at least to the international rock community, was the Family Dog, the Denver venue that managed to host an impressive assortment of visiting luminaries when psychedelic rock peaked in 1967 and 1968, including Buffalo Springfield, Jefferson Airplane, Big Brother & the Holding Company, the Fugs, the Byrds, and Quicksilver Messenger Service:

Another section of the mini-museum details the Grateful Dead’s Colorado concerts, which is kind of taking liberties, even if the Dead had a devoted following in the state. A bigger one documents Caribou Ranch recording studio, which cut sessions by numerous stars in the 1970s and first half of the 1980s, including Chicago, the Beach Boys, and Elton John. The vintage equipment used in the studio that’s on display looks positively antique in the 21st century.

A museum like this is bound to disappoint picky aficionados, and here are a couple performers it could cover who were omitted, or barely represented. Dead Kennedys singer Jello Biafra, not referred to at all in the displays as far as I could reckon, is from Colorado. Although he and that band made their mark in San Francisco, the hall as previously noted has some content on other performers with Colorado origins who went on to fame elsewhere.

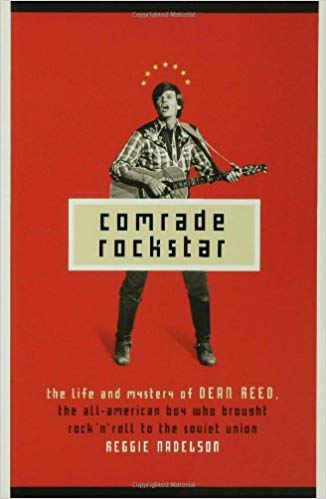

There’s a picture of Dean Reed if you look hard enough, but no text or display explaining his quite interesting, even unique, career. Reed’s music wasn’t so notable, but his life was pretty fascinating, as the Denver native experienced unexpected stardom in South America despite managing just one low-charting entry into the Top 100 in the early 1960s. More intriguingly, in the 1970s he moved to East Germany, becoming a pretty popular entertainer behind the Iron Curtain—and supporter of communist/socialist politics in the region—before his mysterious death by drowning in 1986. I don’t know whether the hall is trying to avoid controversy or offending visitors by barely or not featuring notable Colorado musicians from the punk and Eastern Bloc scenes. But their stories are a lot more interesting than, say, Firefall’s, which gets a good chunk of coverage.

I’m not sure the Colorado Music Hall of Fame gets any visitors who come to the state especially to see the museum, as many do to see the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland. Of course, that’s not its purpose. It’s one of many things to do in Colorado, which is more remarkable for its numerous stunning natural features. Here are some that I visited during my trip:

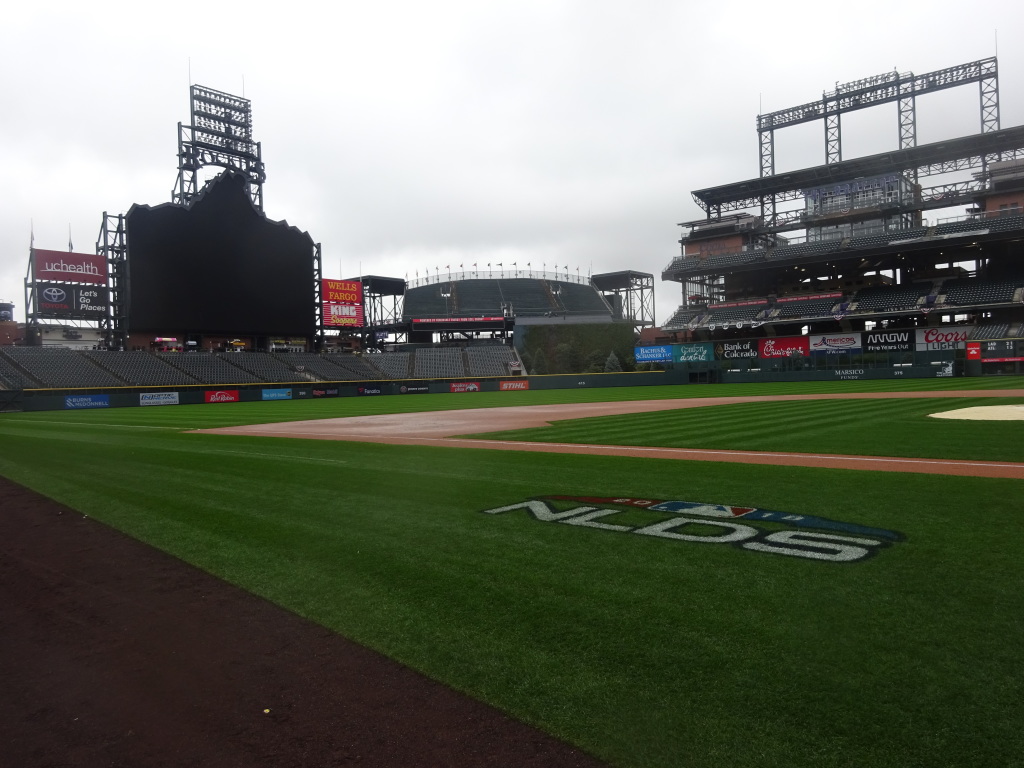

Coors Field, on my tour of the stadium the day after the Colorado Rockies were eliminated from the playoffs. Writing hawking the NLDS series has yet to be removed from the third base lin.

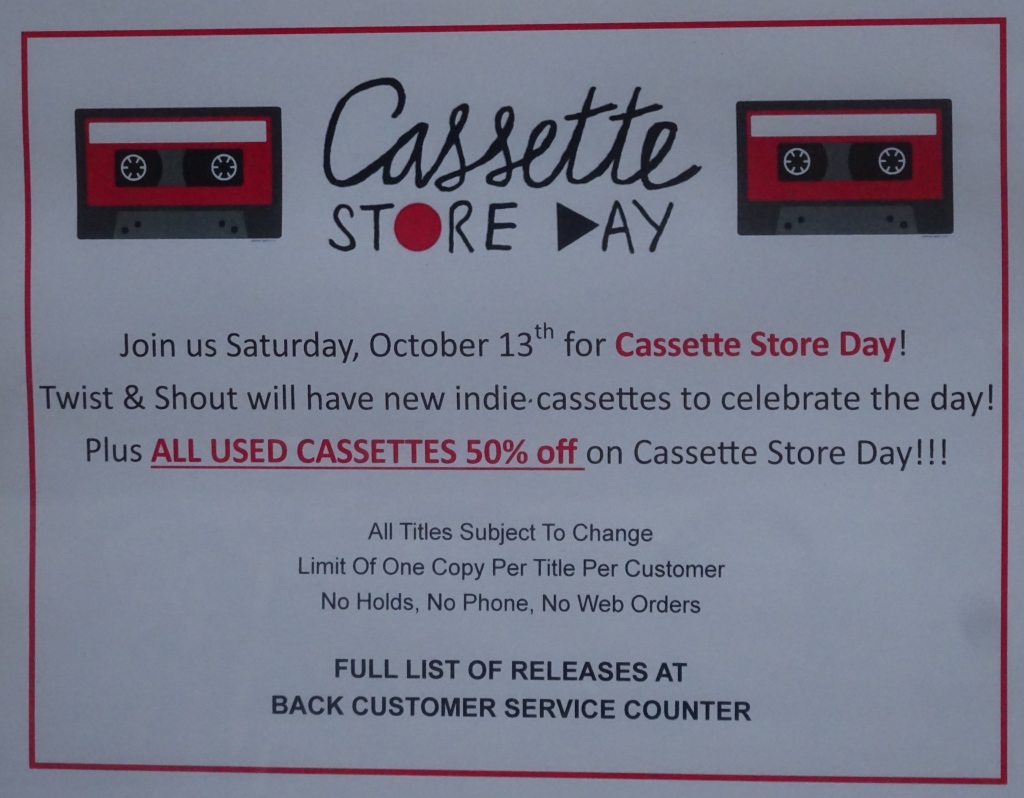

And if you do need to do some record store shopping in Denver, the best shop is Twist and Shout, which had a Cassette Store Day during my visit. Yes, not a Record Store Day, but a Cassette Store Day: