There was an avalanche of reissues in 2018, even if your interest, like mine, is mostly confined to pre-1975 rock, and mostly to the 1960s within that era. The sheer quantity of releases isn’t much different than it’s been in the past few years, but there are a couple of small trends worth noting.

One is the growing presence of expanded editions, sometimes radically so, of classic albums (or even albums that never sold much or got much critical attention). In part that’s because 2018 saw the 50th anniversary of several iconic LPs from 1968, which gave the excuse for expanded editions of Electric Ladyland, The Crazy World of Arthur Brown, Beggars Banquet (which wasn’t so expanded, actually), and most notably The White Album.

But even some records that didn’t have round-number anniversaries, like John Lennon’s Imagine and Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks (neither of which made my list), got large multi-disc sets with elaborate liner notes and packaging. So did one that was allegedly one of the lowest-selling LPs in the history of Columbia Records (Skip Spence’s Oar).

As to why this is happening, maybe that’s the subject for a future post of its own. Figuring out what’s going on isn’t rocket science, though. The industry’s running lower and lower on vault product to re-release, so there isn’t much alternative to going deeper into those vaults to put out unreleased stuff that might have been considered too financially risky or uncommercial even a few years ago. And artists who were more resistant than, say, Dylan or Frank Zappa to opening their vaults—like the Beatles—are, a bit belatedly, realizing the commercial benefits of such archival digs.

Just as importantly, they seem to be realizing that all these outtakes don’t dilute their legacies. Quite the contrary—they enhance them, and are widely appreciated, with intelligence, by fans who can distinguish between the final album and working/early versions never initially intended for public consumption.

Sometimes those expanded editions do seem like an excuse to market something without much actual benefit to the consumers. Beggars Banquet, unlike all of the other 2018 editions cited above, offered little in the way of extras, other than an original mono mix of “Sympathy for the Devil” and a flexidisc with an interview Mick Jagger gave to a Tokyo journalist in April 1968. As Rolling Stones fans know, there are numerous outtakes from the Beggars Banquet era that could have been used for a multi-disc set on par with the more elaborate 50th anniversary editions that did make my list. Don’t rule out this actually happening in the future, say for the 60th anniversary of Beggars Banquet, though by that time many of the listeners who bought the LP on its initial release won’t even be around anymore.

The other small trend? Record Store Day releases are putting a greater accent on material that hasn’t been previously available anywhere, and may not be available anywhere else in the future. Because so much RSD product is devoted to vinyl editions of recordings that have been in circulation for a long time, buyers like myself don’t particularly care about repurchasing what they already own, even if it’s in different formats or glossy packaging. So we haven’t gotten as excited about it as many fellow collectors and store employees might expect.

This spring, however, marked the first RSD when I really did want to make sure to get some of these limited releases as they marked the first and perhaps only time you could buy the material. A few of them made this list. There weren’t as many such items on RSD’s fall list, and I didn’t even buy any of those. But the bigger Record Store Day has always been in the spring, so we’ll see if this happens again in 2019.

Regardless of industry intentions, there were enough reissues—or, to be precise, releases with archival material, often as compilations or first-time appearances of previously unissued recordings—to fill a Top 25 list. My #1 pick shouldn’t surprise anyone who knows me well or has followed my writing. #2 and #3, however, might, as one falls well outside the era that’s my main concentration, and the other is by perhaps the most obscure artist on this list.

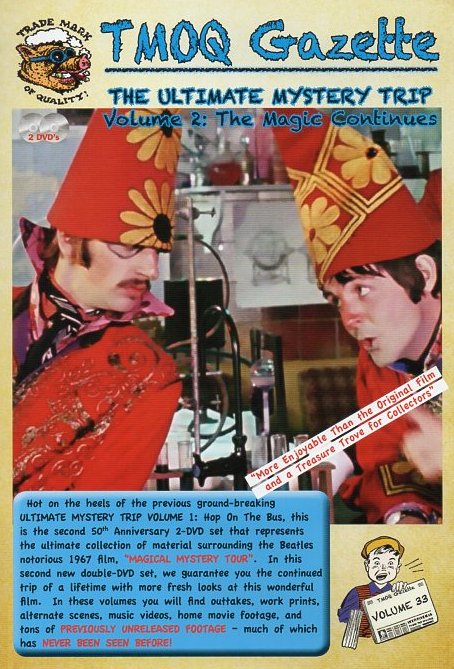

1. The Beatles, The White Album (aka The Beatles) seven-disc deluxe version. This might have been the most hyped reissue of 2018, in a year that saw several other high-profile super-deluxe editions (some of which are reviewed elsewhere in this post). Like the Beatles themselves, this was worthy of the enormous hype it was given. The remix by Giles Martin got the most attention, but the four discs of previously unreleased bonus material are far more noteworthy, as three of them contain studio outtakes that for the most part hadn’t even been bootlegged. The fourth features perhaps the most significant previously unissued body of material the group ever taped—quite a milestone, considering the enormous quantity of unreleased music they recorded while active.

Detailed commentary on this deluxe edition could fill up a lengthy post of its own. (Commercial: I’ve incorporated much commentary on the previously uncirculating studio outtakes into the ebook version of my book The Unreleased Beatles: Music and Film). Here I’m not going to analyze the remix, as I’m not as excited by or interested in such things as many listeners are.

The so-called Esher Demos on disc three are really what make this deluxe edition a vital project. These are the 27 tracks the Beatles recorded at George Harrison’s home in May 1968 shortly before starting to work on The White Album in the studio. These showcase the group “unplugged” before that term was coined, playing acoustically but as a joyous ensemble, despite the tensions already at work that would lead to their breakup. Most of the tracks are early versions of White Album songs that are sometimes quite different in their folky, looser, more carefree manner (the campfire singalong version of “Revolution” being the top example). There are some songs that didn’t make The White Album, too, though they’d mostly show up on post-Beatles solo projects.

The execution’s a bit ragged sometimes and the sound imperfect (though improved from the bootlegs on which they’ve long been available, just seven of them having been released on Anthology 3). But these working versions are largely complete or almost-complete, and make for a superb listening experience on their own, whether as part of this huge box or not. Note, by the way, that the version of George Harrison’s “Sour Milk Sea” (not previously available on a Beatles record, although it was given to fellow Apple artist Jackie Lomax) is a slightly different take than the one that’s been bootlegged. That means there are actually 28 known Esher demos, and it makes you wonder whether there are other alternative versions that haven’t yet circulated.

The three CDs of studio outtakes can, to be frank, be a bit underwhelming in the company of the finished record and the Esher Demos. Usually they’re clearly works in progress. Sometimes they’re just backing tracks; sometimes the songs are unfinished run-throughs; sometimes the arrangements aren’t a whole lot different from the familiar versions; sometimes they’re distinctly inferior to the finished product (like the plod through an early twelve-minute version of “Helter Skelter”). But sometimes they’re pretty different, like the harder-rocking “Cry Baby Cry,” the quite frisky “Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except Me and My Monkey,” and a superb “take 17” of “Helter Skelter” (using the rearrangement heard on the LP version) with a wildly exuberant McCartney vocal. The outtakes are certainly worth hearing, but like the bonus material on several of the other expanded editions reviewed in this post, usually more valuable for history than sheer entertainment.

The Beatles seem to have finally caught on to the potential of expanded CD editions, and not only with the abundance of rare extras. The book-length liner notes are extremely informative and perceptive, with lots of cool photos and memorabilia. Yes, the package is expensive – probably too expensive, considering almost everyone who buys it will already have the two core White Album discs, sometimes in a few formats. Is it nonetheless essential? The answer to that’s yes too.

2. Liz Phair, Girly Sound to Guyville (Matador). From the time of its release in 1993, Liz Phair’s Exile in Guyville was justly hailed as one of the finest albums of its era. At the time, it seemed like she’d emerged from nowhere. She had, however, made quite a few lo-fi solo recordings, circulated on cassettes known as the Girly-Sound tapes, that had helped pave the way for fuller studio recordings and a deal with Matador Records. Not long after Exile in Guyville, these tapes started to circulate to a much wider audience, also getting bootlegged. Eventually some were released on the 1995 Juvenilia EP and as bonus tracks on 2010’s Funstyle, though the majority remained officially unavailable.

The three-CD 25th anniversary edition of Exile in Guyville, going by the title Girly Sound to Guyville, finally makes all but two of the forty songs from the original three Girly-Sound tapes widely accessible in one place. While disc one of this set is wholly devoted to the original Exile in Guyville album, the other two CDs present the Girly-Sound material in its near-entirety. These aren’t just extras of interest to dedicated fans. They are among the most notable bodies of unreleased work cut by any significant artist, and not only because of their considerable historical importance. They’re also outstanding songs and performances, some of which have not found a place in any version on any other Phair release.

For those who haven’t heard yet any of the Girly-Sound tunes, it should be clarified that they don’t exactly equate to an early version of her debut album. Just seven of the songs would show up in re-recorded (and sometimes substantially reworked and retitled), full-band renditions for Exile in Guyville. Some of the others would show up (again, sometimes in retitled and substantially reworked guises) on future Phair releases, such as “Whip Smart,” later used as the title track of her second album (and far superior in its earlier incarnation). Quite a few are unique to the Girly-Sound tapes, and quite a few of those compositions are very good. Even the relative throwaways are pretty interesting and entertaining.

After listening to hissy tapes and bootlegs of the material for quite a few years, it’s a pleasant shock to hear these tracks in very clear, clean fidelity. Although the cassettes were sometimes labeled lo-fi, that has more to do with the basic nature of the recordings—done on a four-track in her bedroom—than the actual clarity of the performances, at least in this sonically cleaned-up version.

Accompanied by nothing but her lightly amplified guitar—sometimes so light it sounds as if she’s not trying to play too loudly or disturb her parents (and the recordings were indeed in her childhood bedroom)—there’s an intimacy that rarely survives into a more polished studio setting. But the compositions are complete, and the singing and playing fully thought out. If there’s a tentative lilt to the proceedings throughout, that adds a fetching vulnerability that likewise didn’t come through nearly as strongly on Exile in Guyville, as fine as that album was in different respects.

But what’s most striking about the material is the songwriting, with a conversational flavor that puts into lyrics what many of us think, but don’t actually express in conversation. Certainly we’re usually not bold enough to state matters as nakedly, and sometimes confrontationally, as Phair does in song here. That wouldn’t mean so much if she didn’t have a gift for engaging melodies that often stretch and shift in unpredictable directions (and often alternate uplifting and melancholy sections) over the course of a song, without sounding contrived or done for clever effect. If Phair doesn’t have the vocal chops of a Joni Mitchell (though “Polyester Bride” has some zigzagging swoops that would do her proud), she has a yearning, unapologetic honesty that’s just as effective.

“Johnny Sunshine,” the X-rated “Flower,” “Fuck and Run,” and “Stratford-on-Guy” (here titled “Bomb”) were all highlights of Exile in Guyville, and it’s cool to hear more basic solo versions. Yet more interesting, however, are numerous otherwise unavailable songs that are on par with anything from Phair’s official discography. In particular, the harrowing “Open Season,” whose apparent depiction of a rape scenario unexpectedly glides into a blissful bittersweet rumination, is not just a match for anything else in her catalog, but a successfully unusual and daring composition by anyone’s standards.

It’s a mystery as to why Phair hasn’t revisited the soaringly melodic “Hello Sailor,” which like another highlight, “GIRLSGIRLSGIRLS” [sic], showcases her gift for very long songs that sustain their interest over quite a few lyrics. “In Love w/ Yself” [sic], another standout, has a rousing anthemic chorus for such a vengeful composition, which like others of Phair’s spells out intimate details of a relationship in unnervingly cinema verité fashion.

Some of the lighter numbers verge on novelty, at least in their subject matter. There are tunes about powering up the “Batmobile,” going to a rodeo town to fuck some cows in “South Dakota,” or parodying the Presley cult (“Elvis Song”) with such bitter viciousness that Graceland would likely bar her from entering if they ever heard it. She also borrows blatantly from some standards for parts of the melodies to “White Babies” (from “My Bonnie”), “Chopsticks,” and her off-kilter mutation of “Wild-Thing” (hyphen included). Even these semi-toss-offs have their charm, though it’s the more serious—sometimes much more, even gravely, serious—efforts that carry the most weight.

Even the most exemplary expanded editions usually don’t quite catch everything, and Girly Sound to Guyville is no exception. Two songs from the original cassettes, “Fuck or Die” (an entirely different song, should you need to ask, than “Fuck and Run”) and “Shatter,” are missing. “Fuck or Die” is a really cool galloping workout, but part of it’s very similar to Johnny Cash’s “I Walk the Line,” and as Phair confirmed on Twitter, “those lyrics—understandably!—didn’t sit well with the Johnny Cash org.” So that prevented clearance for release.

Similarly, the earlier version of “Shatter” (re-recorded for Exile in Guyville) couldn’t be used as the backup singing on the Girly-Sound version quotes too liberally from the Rolling Stones’ “Shattered.” A pity, as it’s a good track that’s substantially different in its earlier arrangement, especially in the overlapping vocals.

And yeah, this deluxe edition also features the actual Exile in Guyville album. As good as that is, after immersing yourself in the Girly-Sound tapes, it sounds rather slick in comparison (though it was a pretty straightforward production, and certainly not glossy). As that record’s been very familiar for the last quarter century, it’s not likely to be the disc most played in this collection, as most of its purchasers will probably have spun it a great deal in years past. But even if it’s not the main concentration of this review, it is a classic album, and one in which Phair triumphantly executed the difficult task of taking her vision from solo bedroom recordings to full-band studio arrangements.

And other than the regrettable exclusion of those two Girly-Sound tracks, Girly-Sound to Guyville is an ideal deluxe edition. The fairly fat booklet features extensive interview material with Phair, Exile in Guyville producer/bassist/drummer Brad Wood, Casey Rice (who also plays on Exile in Guyville), and some more obscure figures who helped build awareness of Phair’s work. As Matador was taking enough of a chance putting out a 18-song, 55-minute debut by an unknown artist, it’s understandable that many of her early songs didn’t make the cut for her official debut release. But it does make you sorry that Exile in Guyville wasn’t a double album, or even a triple. The extra songs are that good.

It was a close call as to whether this or The White Album would make #1 on my list. Although The White Album is undeniably of greater historical importance, the bonus material on Girly Sound to Guyville is of undeniably more consistently high quality. Indeed, it’s of higher quality than the extras on almost any other expanded edition of an album, whether from 2018 or anytime else. The immense stature of The White Album was ultimately the tipping point in giving it the nod. But Exile in Guyville was a hugely important album too, and finishing second to the Beatles’ impossibly high bar is no cause for embarrassment.

3. Catherine Ribeiro + Alpes, Paix (Anthology). Reading about something as “hard to describe” or “unlike anything else” is usually a ticket to disappointment when you’re reading reissue reviews. Often the records are nothing of the sort, whether because they’re derivative or just not that good. This 1972 French album, however, really is unusual, and in a good way, not just a weird way. You know you’re in for something off-the-wall when Ribeiro wordlessly la-las her way through the opening track like a punch-drunk Kerrilee Male (from the late-’60s UK-based folk-rock band Eclection; look ‘em up). Ribeiro more often speaks-chants with an urgent coarseness, though she has a wide vocal range that can vary from Nico-low to stratospheric eerie highs.

More interesting than her singing (which is still oft-thrilling), however, is the music, which after a couple moderate-length cuts gives way to two epics (one nearly 16 minutes, the other nearly 25). While it’s somewhat in the psych-prog mode, there’s an almost spiritual intensity to the blends of churchy organ swirls, loping bass, and almost trance-like ensemble buildups. The mood is often ominous and gothic, yet exhilarating, like a soundtrack to some sort of transcendental journey. It’s not easily comparable to other rock from 1972, and better than her other albums of the late 1960s and early-to-mid-1970s, which are generally more avant-garde and less accessibly high-spirited.

Every other record on this list is “archival” in nature, whether it’s an expanded version of a classic album; previously unreleased live or studio material; or a compilation, whether a box set, best-of, or some other assembly of cuts from various sources. It’s rare these days, and has been rare for quite a few years, that I come across a vintage album I haven’t heard that really excites me. Paix, which I found only because I was house-sitting at a friend’s, is one such record (reissued on vinyl only by Anthology, by the way, though it marks the first time it’s been issued by a US label). That’s almost as much of a thrill as the record itself.

4. The Who, The Who Live at the Fillmore East 1968 (Universal). Even in the numerous unofficial 1960s Who live recordings that have circulated for decades, nothing’s emerged with decent fidelity from before April 5, 1968, when they played the first of two dates at the Fillmore East. This two-CD set marks the first official release of material from the April 6 show.

Especially for those unfamiliar with the tracks that have previously been bootlegged from the April 5 and April 6 concerts, the set will come as something of a surprise. Some of the songs are concise, faithful performances of the early hits that made them stars in their native UK and a burgeoning cult act in the US, including “I Can’t Explain,” “I’m a Boy,” and their first substantial American hit, “Happy Jack.” There are also a couple favorites from their second LP: the mini-opera “A Quick One While He’s Away” and “Boris the Spider,” probably the most beloved John Entwistle composition.

Yet there are also a good number of classic rock covers the group hadn’t yet put on their records, and sometimes never would on their discs. It’s not too unusual to hear “Shakin’ All Over” (which wanders into a riff from the Spencer Davis Group smash “I’m a Man” at one point) and Eddie Cochran’s “Summertime Blues,” both of which would feature on Live at Leeds, recorded just under a couple years later. Less expected are two other Cochran tunes, “C’Mon Everybody” and the far more obscure “My Way” (so obscure, indeed, that it was mistitled “Easy Going Guy” on early bootlegs).

They also tackle “Fortune Teller,” the Allen Toussaint-penned early-’60s New Orleans R&B classic (recorded in 1963 by fellow UK bands the Rolling Stones and the Merseybeats), disclosed in Pete Townshend’s introduction to have been played for the first time at these shows. And it shows—though it’s a heavier arrangement than the Stones’, the harmonies audibly falter at the end of the first verse. There’s also the off-the-wall “Little Billy,” commissioned as an anti-smoking commercial by the American Cancer Society, that Townshend announces as a possible upcoming single, though it’s hard to see it getting issued in the wake of their recent breakthrough US Top Ten hit “I Can See for Miles” (not played at this show, oddly enough). It didn’t appear on a single, or at all until 1974’s Odds & Sods collection.

Most adventurous of all are two songs stretched out way beyond the length of their studio versions. “Relax,” a quasi-psychedelic highlight of late 1967’s classic LP The Who Sell Out, is drawn out to a full eleven minutes, with some extended way-out wobbly Townshend guitar soloing, the riff from Tommy’s “Underture” surfacing at one point. Not music to “Relax” to by any means, it’s intense improvisation, with Townshend, Entwistle, and Moon rocking louder and harder than any other trios of the day, rivaled only by Cream and the Jimi Hendrix Experience in those departments.

A 33-minute “My Generation”—you read that right, 33 minutes, not three minutes—takes up all of CD two. It’s arguably too long, especially if you thought the 14-minute one on Live at Leeds was enough. It’s certainly different, though, and a signpost to where the Who were going in their onstage act, which would get harder, louder, and longer as the ‘60s turned to the ‘70s. Also different, though not much longer, is “A Quick One,” which inserts the lyric “you are forgiven by the very act of creation” in its finale.

For those familiar with the bootleg from an acetate that Who manager/producer Kit Lambert made of performances from the Fillmore East shows, some of this new release—plainly titled The Who Live at the Fillmore East 1968—will overlap with what they already have, though the fidelity’s better. And the absence of the April 5 cuts that did make it onto the acetate means you don’t have to throw away that boot yet, though the April 6 versions are similar. In all, however, it’s a fine and worthy document of the Who as they made inroads into the United States, and moved away from their power pop base to a heavier, more spontaneous approach, onstage at any rate. (A much longer review of this release, including comments from my interview about it with longtime Who sound engineer Bob Pridden (who mixed the release and was already working as the band’s soundman at the actual Fillmore East shows), appears in this issue of Record Collector News.)

5. Pete Townshend, Who Came First 45th Anniversary Expanded Edition (Universal). Who Came First gave Pete the chance to present rather gentler, more introspective tunes than he usually penned for the Who, and to be the only (as opposed to the occasional) lead singer in his thin, high, wavering, yet engagingly heartfelt voice. Universal’s two-CD expanded edition puts a remastered version of the album on the first disc, and seventeen bonus tracks, some previously unreleased, on the second. Such is the quality of the original LP that this would rank higher on this list had this been the first CD release of the record. It’s not, however—and not even the first (or second) time it’s come out with bonus tracks—and so has to be judged on a reissue best-of primarily for what it offers that hasn’t been previously available.

And there’s not all that much in that department. The first seven songs all appeared as bonus cuts on Hip-O’s 2006 extended edition, six of them taken from privately pressed 1970s various-artist LPs primarily circulated within the Meher Baba community (though these were naturally quickly bootlegged). Although sometimes more primitively produced than the Who Came First tracks, these were generally in the same league and of the same vibe, highlighted by Townshend’s solo version of the Who hit “The Seeker”; the languid, melancholy “Day of Silence,” which easily measured up to the best of Who Came First; “Mary Jane,” a country-flavored hoedown not far in tone from Ronnie Lane’s similar efforts of the same era; and a left-field, but quite good, version of Cole Porter’s “Begin the Beguine” (chosen as it was one of Meher Baba’s favorite songs). A wholly instrumental, synthesizer-dominated version of “Baba O’Reilly”—again taken from one of the limited-press Meher Baba LPs—is a welcome presence here, especially as it hasn’t been used as a bonus cut on previous Who Came First CDs, though the bluesy outtake “I Always Say” is pedestrian.

That leaves nine previously unreleased tracks, and while those are the main attractions for Who/Townshend completists, they’re also not as interesting as the other extras. “The Love Man,” a nice slice of assertive romanticism, is puzzlingly subtitled “Stage C,” and not too different from the version used as a bonus cut on previous expanded editions; a variation on “Content” subtitled “Stage A” has a plainer arrangement than the LP version, and suffers from its sparseness. There’s also a ghostly, largely instrumental version of “Day of Silence” that doesn’t measure up to the one that made the cut. An alternate of “Parvardigar” is missing the synthesizer doodlings and percussion that punctuate the Who Came First track, sounding more intimate and low-key, if less creatively adorned. And there’s an incomplete solo acoustic take (still lasting four minutes) of “Nothing Is Everything,” aka “Let’s See Action.”

Disc two closes with four songs that haven’t previously been attached to Who Came First editions in any form, though a couple don’t really belong here. On the plus side, we finally get to hear the pleasing, if non-earthshaking, wistful midtempo folk-rocker “There’s a Fortune in Those Hills”—described in the May 14, 1970 issue of Rolling Stone as a “slow wailing country song” earmarked for the Who’s next studio LP, though this is the first time it’s circulated in any guise. The instrumental “Meher Baba” in Italy is a likewise pleasant-but-minor instrumental combining synthesizer washes with guitar, which sometimes simulates mandolin-like patterns suitable for cruising canals on the gondola.

The final pair of tracks that don’t belong here, frankly, though at least the first is good. The solo acoustic performance of Quadrophenia’s “Drowned” was recorded live in India (without an audience) in 1976, featuring mighty hasty strumming and, of course, Townshend’s vocal in place of the familiar one by Roger Daltrey in the Who’s version. The live performance of “Evolution” that concludes the set was recorded at a Ronnie Lane memorial concert in 2004, and it’s obvious from the deepened voice of Townshend’s spoken introduction how much time has passed since the rest of the material on this release was recorded.

Although this 45th anniversary deluxe edition of Who Came First is the longest version of the album yet released, it’s not definitive. It’s missing “Lantern Cabin,” a nice delicate, moody piano instrumental (first released, like “His Hands” and “Sleeping Dog,” on the 1976 Meher Baba tribute LP With Love) that’s appeared on previous Who Came First expanded editions. Certainly it should have been given precedence over the live performance of “Evolution.” Even hardcore fans might feel short-changed by the relative paucity of actual brand new material on the two-CD set, though that’s the way it often is with deluxe anniversary editions.

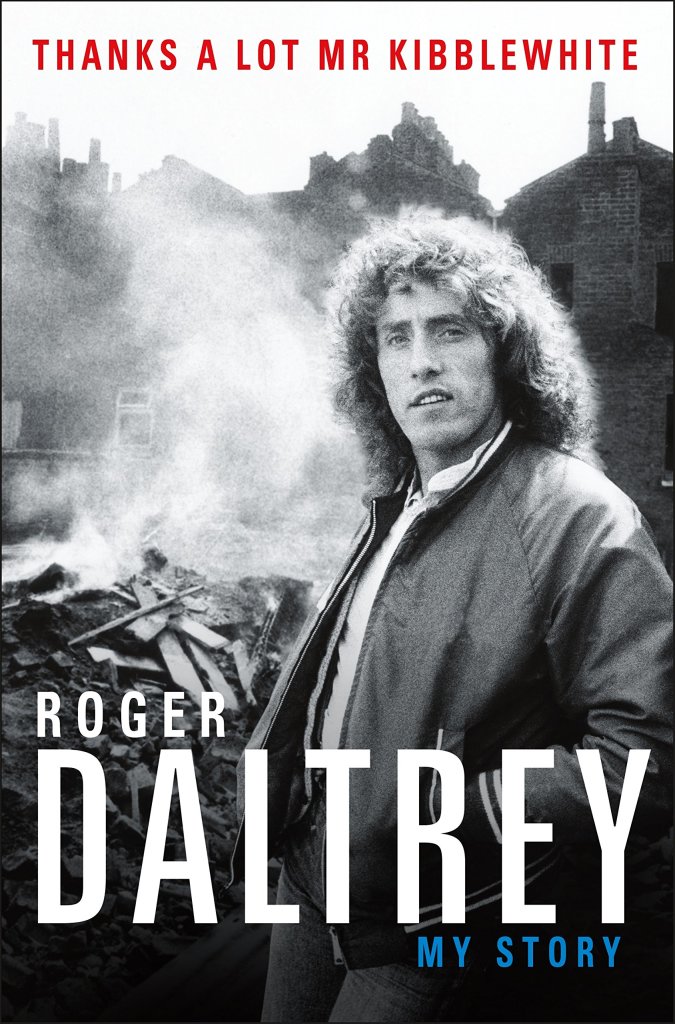

At least you get Pete Townshend’s liner notes. And if you want to read more from the Who, Roger Daltrey’s autobiography came out in the fall. (A longer version of this review appears in the issue of Record Collector News.)

6. Bob Seger & the Last Heard, Heavy Music: The Complete Cameo Recordings: 1966-1967 (ABKCO). Seger became a superstar by helping define album-oriented rock from the mid-1970s onward. It’s not so well known, unless you were in Michigan at the time, that his career began with fairly raw singles that went into gritty garage rock, blue-eyed soul, and even protest hard rock. For many years, this material was way up the list of recordings that deserved reissue, but had never came out on CD or LP. There were unauthorized collections if you really needed to hear it, but even those weren’t that easy to come by, and didn’t boast the best sound quality.

So this official compilation of all ten tracks from his five singles on the Cameo label is welcome, especially as it has better fidelity and good, if not super-lengthy, liner notes that put his early career in context. About half this stuff is really ferocious, especially “East Side Story,” whose tale of urban crime gone wrong almost sounds like Bruce Springsteen as garage rocker; “Persecution Smith,” a great knockoff of Bob Dylan’s “Tombstone Blues”; and the frenetic garage-pop-rock of “Vagrant Winter.” Some of these singles were actually regional hits in Detroit, and the soul-rock “Heavy Music” even made a bit of national noise before the Cameo label’s problems helped snuff its prospects.

Not everything here is that great. “Florida Time” is a weird Jan & Dean-style paean to spring break; “Very Few” a forgettable ballad; and part two of “Heavy Music” and the instrumental version of “East Side Story” (“East Side Sound”) were kind of B-side filler. But at least these, as well as the seasonal James Brown tribute “Sock It To Me Santa,” testify to his unusual versatility. The one serious flaw to this package is one that couldn’t be avoided: all of his Cameo sides add up to just 28 minutes of music. And because it’s not in the Cameo catalog, it’s missing his first single after he moved to Capitol, the smoking “2+2=?,” one of the best and hardest-hitting anti-war songs of the Vietnam era. (My full article on this compilation is online here.)

7. The Lost Souls, The Lost Souls (Lion Productions). “The Lost Souls never released any records, yet the recorded evidence that survives indicates that they were one of the finest unknown American groups of the mid-’60s, able to write both catchy British Invasion-type rockers and, in their latter days, experimental psychedelic pieces with unusual tempo changes and song structures.” That’s how I started my All Music Guide bio of Cleveland’s Lost Souls. It’s also a blurb on the back on this CD, though I wasn’t aware it would be placed there until I saw a copy.

It’s a lengthy breathless sentence-long summary of a band that packed a lot of hard-to-peg originality into their short lifespan. And I stand by it, though few others heard their scant body of recorded material, as they never managed to put anything onto disc while they were active. A cassette-only release of their best tracks came out way back in 1983, but I know just two other collectors besides myself who got a copy.

This CD compilation rectifies that long-standing gap and then some. Not only does it include all ten songs from the cassette, but it also has some live recordings; an alternate version of one of the cassette’s songs, “Things That Are Important”; and a few other odds and ends from their earlier days. Seven bonus tracks spotlight post-Lost Souls recordings by one of the band’s singer-songwriters, rhythm guitarist Denny Carleton, in the Choir and Moses, as well as some of his solo efforts.

It’s those first ten tracks, however—presented here in cleaner fidelity, sometimes drastically so, from the cassette release—that show the group at their best, even if they’re almost unsettlingly diverse. They veer from straightahead catchy British Invasion harmony dressed pop-rock to blue-eyed soul and odd collisions of accessible pop and psychedelic weirdness. Unlike almost every other garage band who never got to make a record, they also branched beyond the usual rock setup to incorporate sax, flute, mandolin, and harpsichord.

Those ten songs would have made a cool LP, though maybe not the one they would have put out had they been able to back in the day, spanning as it does different phases of their brief evolution. The previously unreleased cuts aren’t as fully developed or original, indebted far more heavily to early British Invasion and surf music, though they round out our view of the band’s too-short history. The best of these, the catchy if basic “Whatcha Gonna Do,” sounds like a drumless demo. (My longer review of the CD, along with an interview with the Lost Souls’ Denny Carleton, will appear in a future issue of Ugly Things.)

8. The Choir, Artifact: The Unreleased Album (Omnivore). The Choir were the best Cleveland rock band of the 1960s, performing what’s now recognized as ancestral power pop with guts, fine vocal harmonies, deft instrumental skill, and quality original material. Their legacy hasn’t been served well on disc, however, either at the time or since then. Despite writing and recording a good number of tracks, they never issued an LP, and remain almost solely known for the December 1966 single “It’s Cold Outside,” a huge local hit and a staple of ‘60s garage reissues. The 1994 CD compilation Choir Practice was frustratingly patchy, missing the ace B-side of “It’s Cold Outside” (the grungy “I’m Going Home”) and only featuring portions of their substantial body of work that was unreleased while they were active.

The Choir went through seven lineups in just four years (1966-70), and this CD at least represents one of them well. Entirely recorded in February 1969, this has organist Phil Giallombardo, guitarist Randy Klawon, bassist Denny Carleton, drummer Jim Bonfanti (the only constant throughout their frequent personnel changes), and pianist Kenny Margolis; all of them sang, and the ten tracks feature material penned by Giallombardo, Carleton, and Margolis. It varies between classic-style harmony pop-rock (“Anyway I Can”), Kinks-ish quasi-vaudeville rock (“Mummer Band”), the best American late-’60s Bee Gees soundalike ever (“Have I No Love to Offer”), and a jazz-Latin-ish instrumental (“For Eric”). Although the approach is heavier than their earlier, poppier sound, unlike so many other acts with similar roots, it’s integrated into the harmony pop-rock songs well. Particularly impressive is the rich piano-organ blend, more identified with Procol Harum and the Band, but shown to be effective in a more pop-oriented context here.

So high marks for the music, but not so much for the packaging. The liner notes are disappointingly skimpy, and do not make it clear whether these tracks were intended to form an actual LP, or are simply sessions done around the same time that have been retrospectively packaged as one. At least the centerfold features an extensive Choir family tree that clarifies who joined and left when. (My interview with Denny Carleton about this release appears in the summer/fall (#48) issue of Ugly Things.)

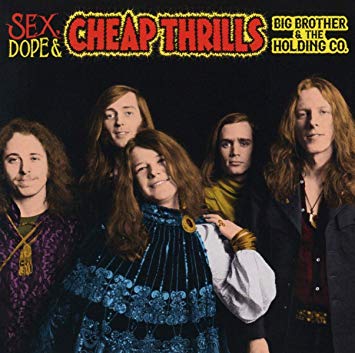

9. Big Brother & the Holding Company, Sex, Dope & Cheap Thrills (Columbia/Legacy). Not an expanded Cheap Thrills (there was already one of those), this two-CD compilation is comprised almost entirely of outtakes from the sessions. Twenty-five of the thirty songs are previously unreleased; the previously available ones are on out-of-the-way or expensive compilations that even committed Joplin/Big Brother fans might have missed; and the one non-studio cut is a good hitherto unissued live version of “Ball and Chain” (Winterland, April 12, 1968). There are good, though not book-length, liner notes by drummer David Getz, and an appreciation by Grace Slick that’s thoughtful and long enough not to look phoned in. And you can get all this as a standalone release, instead of having to buy it as part of an expanded Cheap Thrills edition that compels you to buy the original album—which you probably already have in at least two formats—all over again. And the double-CD sold for a reasonable $14.98 plus tax at my local record store. Hey, labels (and artists), pay attention: this is the way to do it!

On to the music — I wasn’t expecting this to rank as high as it does here. But hey, it’s quite an occasion when you want to play two lengthy CDs’ worth of alternate versions of songs you’re real familiar with three times in three days. While none of them are drastically different from the ones on Cheap Thrills (or elsewhere, for the songs here that didn’t make the cut for the LP), they’re different enough to make for enjoyable, at times compelling listening — even the occasional take breakdowns. And while all seven of the songs from the LP are represented by different takes/performances, there are no less than nine others (again, sometimes in multiple versions), most of them group originals. While these are generally not up to the standard of the final selections (“Farewell Song” being a notable exception), they’’e decent enough, and their inclusion gives us a much more rounded view of the band’s repertoire at their peak.

While I’ve met David Getz a few times, like him, and appreciate his making himself available to me for an interview and speaking once to one of the classes I’ve taught, I’ll here offer a couple differing opinions to minor comments in his notes. Of “Summertime,” he writes, “I’m pretty sure it had never been recorded by a rock band.” Not so — the Zombies did it on their first album, the Doors had done it live as an instrumental (as heard on their March 1967 tapes at San Francisco’s Matrix club), and for all I know there might be others. He does add, “Especially a band like Big Brother & the Holding Co.,” which I think is right.

He also expresses regret that Clive Davis insisted the brief avant-garde piece “Harry,” originally intended to open side two, be removed, and that the band didn’t stand their ground and insist it stay. I’m not a Davis fan, but I have to agree with him in this instance. It’s not a tuneful track — in fact, it’s pretty grating. And while I don’t care whether it would have impacted the LP commercially, you can see Davis’s reasoning — putting it at the beginning of side two would have had many listeners reaching for their needles to skip the song, not nearly as easy a thing to do as it would have if it had been placed at the end of a side.

But let’s end this positively with a couple points of praise not often made about the band, especially considering that most of the record is fun to hear. Even though they were sometimes criticized for not being able to play well, or at least match the intensity of their live performances, in the studio, I really like how you often hear Joplin (and sometimes guys in the band) whoop unpredictable shouts of joy. If it really was laborious to record in the studio, it certainly sounds like they were having lots of fun at least some of the time. And overall, the collection reinforces my incredulity that Big Brother were sometimes criticized — at the time, and since — for not being good players, or not an appropriate match for Janis’s genius. These guys could play, and if it’s with more heart and imagination than polished technique, well, I’ll take those qualities over studio slickness any day. This music captures both Janis and Big Brother at their peak.

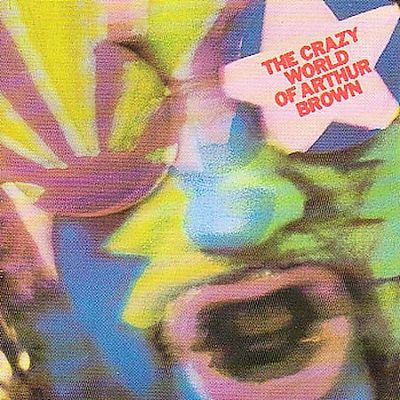

10. The Crazy World of Arthur Brown, The Crazy World of Arthur Brown 50th Anniversary Super-Deluxe Edition (Cherry Red). Featuring the song that sent them to brief stardom, the Crazy World of Arthur Brown’s sole, self-titled 1968 LP was a psychedelic supernova that seemed not so much to launch the band as consume it. Its mix of acid rock, operatic-to-histrionic Brown vocals, demonic lyrics, and berserk Vincent Crane soul-jazz organ runs was maddening yet exhilarating, sounding like nothing else on the ultra-competitive British psychedelic scene. But it used up virtually all of their known first-rate material, and less than a year after it hit the UK and US Top Ten, the band were gone.

How in the world, you may wonder, can you make a four-disc box out of an LP without any outtakes and few non-LP singles? It’s a fair question, but the package is pretty good value, even if there’s inevitable repetition of most of the album’s songs (sometimes in six or seven different versions).

Disc one has the stereo mix, with bonus non-LP singles and 45 mono mixes; disc two the mono mix, with bonus alternate mixes, an early version of “Fire,” and “Nightmare” as heard (not too differently from the record, to be frank) in the film The Committee. And disc three has their slim body of 1968 BBC radio recordings, as well as the four rare cuts Brown recorded before the Crazy World formed. Fattening up the LP-sized box is an actual vinyl 12-inch version of The Crazy World of Arthur Brown, in stereo with a sleeve boasting the original artwork.

This does mean you get the core album on no less than three of the box’s four discs, but there are significant differences between the stereo and mono versions. To me, the stereo’s considerably and unquestionably superior, as the mono sounds hollow—particularly in the vocal department—to the point of lacking completion.

More significantly, among disc two’s bonuses are mysterious “alternative mono” mixes of the songs comprising side one of the original LP, done before brass and strings were added. These have odd spoken links—some by Brown, some by his first wife—that, if they don’t add to the record’s psychedelic seance atmosphere, do fit in more or less. It’s like hearing an appreciably different version of side one of the LP, the spoken bits adding to the feel of a quasi-concept album, even if the concept remains pretty indistinct.

Other significant extras are the three non-LP bonus tracks on disc one, even if none were good enough to demand a place on the original Crazy World of Arthur album. The pre-LP 1967 single “Devil’s Grip”/”Give Him a Flower” mixed their burgeoning devious brand of psychedelia (on the A-side) with a flower-power satire (on the B-side), though “Devil’s Grip” wasn’t as powerful as the material on the album, and “Give Him a Flower” rather forced and lame comedy. Used as a 1968 B-side to “Nightmare,” “What’s Happening” is okay and very much in keeping with the band’s sound, yet overall rather forgettable compared to most of the LP’s material.

Committed Crazy World fans probably have most or all of the tracks on the first two discs, with even the rarities having often gained exposure on various other reissues. At least they’re less likely to have everything, or maybe even anything, from the third CD of rarities and radio broadcasts. The four songs from the April 8, 1968 BBC session—all in fine fidelity, with Ron Wood guesting on bass, and all (including “Fire”) to appear on the LP—were, in original drummer Drachen Theaker’s opinion, their best recordings. They weren’t; maybe Theaker’s view was colored by getting submerged in the album mix after Ahmet Ertegun complained about his time-keeping. But they’re good, and less ornate than the LP arrangements.

Also included is a June 30, 1968 BBC rendition of “Spontaneous Apple Creation” with a notably bumpier tempo than the studio counterpart. Four songs from a 1968 Swedish radio broadcast, in more variable but quite listenable sound quality, have also been retrieved, including one (“Nightmare”) that didn’t make the BBC batch.

The four pre-Crazy World cuts ending disc three are the rarest of the set, yet the least impressive. The three numbers billed to the Arthur Brown Set were recorded in Paris with local soul band the Sharks for the Roger Vadim film La Curée. Other than Arthur’s emergent The Devil in Tom Jones vocal mannerisms, these are very run-of-the-mill R&B-rock tunes, and “The Green Ball” not even up to that meager standard. Done yet earlier, his 1965 cover of Peggy Lee’s “You Don’t Know” (issued only on flexidisc) is better, though rudimentary compared to the fireworks he’d unleash as the Crazy World’s frontman. Adding considerable value to the box, the 24-page LP-sized booklet has extensive liner notes by Mark Paytress that tell the confusing story of the Crazy World of Arthur Brown (involving numerous personnel changes in its last year or so, including a stint by Carl Palmer on drums) better than any previous print source. (A longer version of this review, along with my interview with Arthur Brown shortly after the extended edition’s release, will appear in a future issue of Ugly Things.)

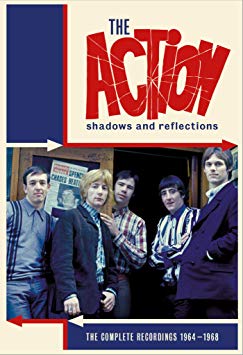

11. The Action, Shadows and Reflections: The Complete Recordings 1964-1968 (Grapefruit). Is there any other 1960s rock group that never released an LP during their lifetime, yet was eventually honored with a four-CD box set? If there was any such box before this, I can’t think of one. But though it took quite a bit of scrounging (including many not-too-different alternate takes) to pump this up to four discs, the Action were worth the effort, as one of the better British ‘60s bands never to have a hit, let alone a full-length album. Sometimes classified as a mod band a la the Who or the Small Faces, the Action were more soul-oriented than either of those acts. They weren’t as good, either, in part because they didn’t write much of their original material during their prime. But they were pretty good, putting more guitar and British pop harmonies into their soul covers than the originals boasted, and then writing a few decent originals.

As for what you might not yet have on this box if you’re already an Action fan, besides all those previously unreleased alternate takes and backing tracks that comprise the whole of disc two, there are also some BBC recordings and TV appearances, some of soul covers not on their singles. (All of those, however, have appeared on other reissues, if rather out-of-the-way ones.) All of the twenty tracks on disc three have likewise appeared on pretty obscure archive releases (though three of the songs are presented at their full length for the first time), and document their uneven evolution from mod-soulsters to mildly psychedelic and early progressive rock. Recorded in 1967 and 1968 after their five singles, and not issued at the time, I don’t think these are nearly as interesting as the cuts from their mod prime. But they are eclectic, somewhat ambitious, and grow on you some with time.

The packaging on this set is excellent, with lengthy historical liner notes by David Wells, and track-by-track annotation from compiler Alec Palao. Unless someone’s sitting on tapes yet to be discovered, it’s a last-word box, at a time when last-word boxes keep getting supplemented by extraneous material.

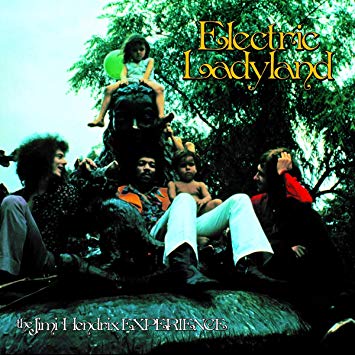

12. The Jimi Hendrix Experience, Electric Ladyland Deluxe Edition 50th Anniversary Box Set (Legacy/Experience Hendrix). What’s most interesting about this four-disc expanded 50th anniversary edition isn’t the original album, though it comprises disc one, digitally remastered from the original two-track tapes. Of more value is an entire disc of rare/unreleased demos and outtakes; a disc of the Experience’s Hollywood Bowl concert on September 14, 1968; and a Blu-ray documentary on the making of Electric Ladyland (not included in DVD format as well, unfortunately). Everything’s encased in a mini-coffee table-sized 48-page hardbook book with liner notes, photos, memorabilia, and reproductions of some of Jimi’s handwritten lyrics, as well as his instructions (not completely followed) for the LP’s original artwork.

About half of the second CD is devoted to home demos Hendrix recorded as Electric Ladyland was taking shape, probably at New York’s Drake Hotel in March 1968. (You can even hear a phone ring in the background during “Gypsy Eyes”). In contrast to most other extant Hendrix recordings, these are low-volume solo endeavors. Although the liners state these were made with a small amplifier, the sound’s soft enough that it seems almost as if he could have been playing an unplugged electric, like he’s making sure not to disturb other hotel guests.

Besides early versions of “1983,” Gypsy Eyes,” “Long Hot Summer Night,” and “Voodoo Chile,” it’s notable for also including songs that wouldn’t make the running order. Among these, the clear standout is “Angel,” later a highlight of Cry of Love. Others, like “Hear My Train A Comin’,” “My Friend,” and “Cherokee Mist,” didn’t even attain the high profile “Angel” enjoyed on a posthumous release. In large part because of the solo, almost unplugged setting, these show a more sensitive side to the man than his celebrated noisefests do. Here as in few other tapes, you can hear the substantial influence Curtis Mayfield had on our hero, both in the fluidly melodic playing and the oft-wistful/philosophical bent of his vocals and songwriting.

On these demos, there’s a sameness to the tunes and arrangements that gets a bit wearisome after the while. But as a chunk of calm within the storm unlike anything else in Hendrix’s enormous catalog of recordings not issued during his lifetime, it has enormous value. It’s not too important, but note that while the liner notes refer to these tapes as unreleased, that’s not exactly correct. Some of them did come out on a CD packaged with the Hendrix graphic novel Voodoo Child back in 1995, though that non-standard release might have been missed even by some serious Hendrix fans.

The early studio versions of Electric Ladyland songs on the rest of disc two aren’t as unusual or revealing, but have their use as looks at the foundations of “Long Hot Summer Night,” “Rainy Day Dream Away,” “1983,” and even “Little Miss Strange” before those tracks had vocals. The playing’s precision impresses, and “Rainy Day Shuffle” is more soul-jazz than rock. The standout, however, is “Angel Caterina,” an early version (with Hendrix vocals) of “1983” with Redding on bass and Miles on drums. While it’s clearly not up to the level of the finished “1983” (and Miles’s drumming is notably weaker than Mitch Mitchell’s would be), it’s the only outtake in this batch that can be appreciated as a relatively complete song and performance, rather than as a mere backing track.

Numerous Hendrix concerts have circulated that have better fidelity and performances than the Hollywood Bowl show featured on disc three. It’s the right move to include this, however, since it hasn’t been previously available; was a reasonably historic occasion, given the prestige of the venue; and fits into the timeline, as Electric Ladyland came out just a few weeks later. The sound quality’s a bit on the rough side since, as the liners admit, it’s a “two-track recording surreptitiously drawn from the house mixing console.” The gig was on the verge of getting disrupted as well, the set getting interrupted several times when fans dove into the pool of water between the stage and the seats. And parts of “Foxey Lady” and “Fire” went missing when the tape reel was flipped.

Still, a clearly excited Experience deliver a fairly good, if a bit rough (if only in comparison to more finely honed concerts of the period), set that’s not as predictable as some of their others from the era. There’s nothing as unexpected as, say, “51st Anniversary” here. But in addition to the dependable favorites “Hey Joe” and “Purple Haze,” there’s a preview of the soon-to-be-released “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)”; an instrumental version of Cream’s “Sunshine of Your Love” (why Hendrix decided not to sing this is mysterious); and, nearly a year before the iconic Woodstock version, “Star Spangled Banner.” “Little Wing,” for all its fame, wasn’t done too often live, so it’s good to hear as part of this set, which also includes a couple of the less played-to-death songs from Are You Experienced, “I Don’t Live Today” and “Are You Experienced” itself. It’s too bad he didn’t preview some more Electric Ladyland goodies like “All Along the Watchtower,” but you can’t have everything.

On the fourth disc, the wordily titled At Last…The Beginning: The Making of Electric Ladyland is a highly worthwhile documentary. Much of the material has been long available as part of an hour-long-or-so episode of the Classic Albums series since the late 1990s, but this version adds almost forty minutes. Besides featuring some vintage footage of and interviews with Hendrix, it includes decades-after-the-fact interviews done with almost everyone who played on or contributed to the album’s production, including Mitchell, Redding, Miles, Casady, Stevie Winwood, Dave Mason, engineer Eddie Kramer, manager/producer Chas Chandler, and even relatively obscure organist (on a couple tracks) Mike Finnigan.

There’s more to be heard from the Electric Ladyland era on some other archival releases, and more to be learned from other documentaries, books, and liner notes. But this deluxe edition largely succeeds in offering a good deal of important, entertaining supplementary material for the record that, other than Are You Experienced, was Hendrix’s best. (A longer version of this review will appear in a future issue of Ugly Things.)

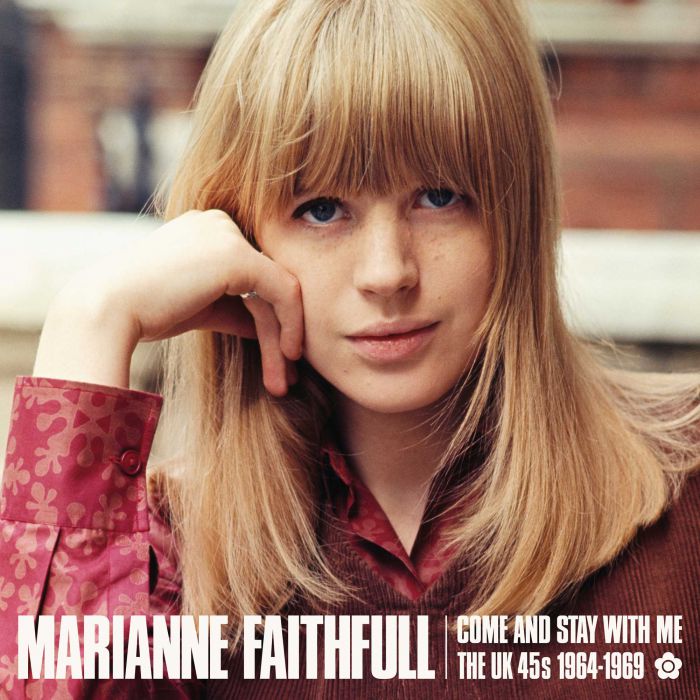

13. Marianne Faithfull, Come and Stay with Me: The UK 45s 1964-1969 (Ace). All of Faithfull’s UK A-sides and B-sides from the 1960s, plus all four songs from her 1965 UK EP Go Away from My World. None of the material on this 22-track CD is rare, and in fact most or all of it’s been reissued numerous times. And while it has much of her best early work, it’s missing some ‘60s standouts from her LPs, like the folk-poppers “With You in Mind” (written by Jackie DeShannon) and “In My Time of Sorrow” (co-written by DeShannon and Jimmy Page), or tracks from her underrated folky 1966 LP North Country Maid. This still comes close to serving as a best-of, with some overlooked classy non-hits and B-sides like “Morning Sun,” “The Sha La La Song,” and “Tomorrow’s Calling,” as well as the surprisingly swaggering, bluesy “That’s Right Baby.”

What is missing is the songwriting skill and tougher, lower-register vocals Faithfull developed by the late 1970s, with the exception of the 1969 B-side “Sister Morphine” (which predates the Rolling Stones’ Sticky Fingers version). But though this might seem lightweight compared to what came a decade later with her Broken English comeback, it’s generally superior British ‘60s pop-rock with a distinctly, almost uniquely genteel quality to both the singing and arrangements. (Albeit there are some mediocre misfires, like her unnecessary treacly cover of “Yesterday.”) It’s also enhanced by thorough historical liner notes—a feature I don’t recall seeing on any previous compilation of her ‘60s studio recordings—with plenty of first-hand Faithfull quotes.

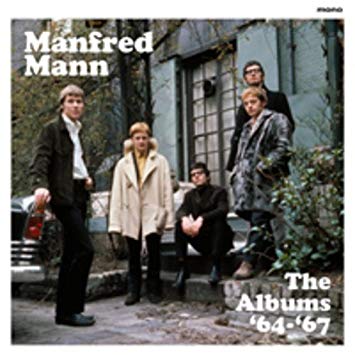

14. Manfred Mann, The Albums 64-67 (Umbrella Music). The Beatles, Rolling Stones, Kinks, and Bob Dylan all have vinyl mono box sets of their early albums. So why not Manfred Mann, even if they didn’t put out many UK LPs in the mid-’60s, and if they weren’t nearly as iconic as those other names? It might be an excuse to repackage tracks that have been around the block many times (though certainly not often in mono). But as packaging goes, it’s real good, each of their first four British albums getting housed in the original artwork, and the inner sleeves boasting fresh historical liner notes by four different Manfreds. There’s also an “exclusive” LP-sized color photo print of the best quintet mid-’60s lineup, if you go for that sort of thing. Much more significantly, there’s a DVD (lasting a little more than half an hour) with pretty interesting, articulate interviews with four of the five core Manfreds (Mike Vickers declined to participate).

And there’s music, too, though nothing that will be unfamiliar to those who’ve carefully collected the mid-’60s era in which Paul Jones was the lead singer. As good as Manfred Mann could be, they weren’t quite as good as the best British Invasion groups, and not all that consistent. So it’s a mixed bag here, featuring a pretty good R&B-based debut LP (The Five Faces of Manfred Mann); a wildly uneven follow-up (Mann Made) mixing generally unmemorable original material and eclectic, but sometimes poorly chosen, cover versions; and a nearly all-instrumental album, Soul of Mann, that’s something of a marginal novelty. The other LP, Mann Made Hits, is actually a compilation rather than a standalone LP, and retrieves most of the big hits and standout cuts that didn’t find a home on their British albums, a la “John Hardy,” their superb version of Dylan’s “With God on Our Side,” their groovy cover of Ben E. King’s “Groovin’,” and the standout autobiographical original “The Man in the Middle.”

For all the tasty window dressing, however, this is missing some pretty good mid-’60s Jones-sung tracks that didn’t make it onto the British LPs for some reason, like Jones’s catchy pop composition “She”; the jazzy original “Dashing Away with the Smoothing Iron”; and the early, pre-hits R&B single “Cock-a-Hoop.” It’s also gotta be admitted that the hits disc really overshadows everything else with its cluster of smashes like “Do Wah Diddy Diddy,” “Sha La La,” “Come Tomorrow,” and “Pretty Flamingo,” even if the group’s heart was more in the R&B and jazz they detoured into on their albums. But am I nonetheless glad I got a review copy? Sure. (Lengthy interviews I conducted in summer 2018 with Paul Jones and Manfred Mann bassist/guitarist Tom McGuinness are in the winter 2018 (issue #49) issue of Ugly Things.)

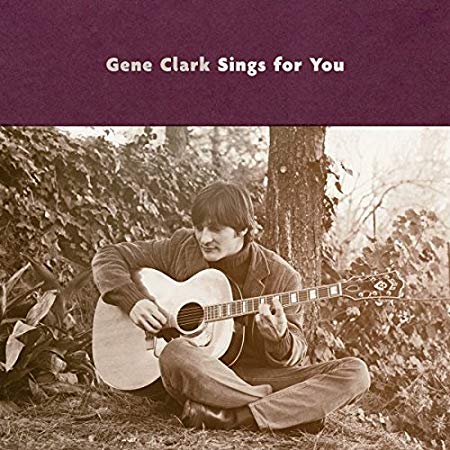

15. Gene Clark, Gene Clark Sings For You (Omnivore). This isn’t exactly a lost album, but it’s probably about as close as we’ll come to hearing one from the primary songwriter of the original Byrds lineup. The bulk of it’s taken from an eight-song acetate of the same name, comprised of sessions that took place near the end of 1967, after Clark had been dropped by Columbia. Five more tracks from a different acetate recorded around the same time, as well as an additional unreleased demo from the era, add up to a full CD of 1967 Clark. Collectors and folk-rock fanatics will be thrilled to finally have the opportunity to hear these rarities, never previously listened to by anyone save a very few.

But like many and maybe most “lost” albums, Sings For You doesn’t deliver what you might wish for in your imagination. The good news for devotees of the “classic” Byrds folk-rock sound is that it’s far closer in sound to the fairly straightforward folk-rock of Gene’s first LP (from earlier in 1967) than to Dillard & Clark’s country-rock-with-the-accent-on-country in the late ‘60s. The bad news, or at least cautionary warning, is that it’s rather crudely executed, though not so much by Gene as by the erratic backup musicians and arrangements he employed.

And the songs, truth to tell, are mostly not up to the level of his first official album, let alone Byrds classics like “I Knew I’d Want You” or “Set You Free This Time.” He’s not so much forging a new direction as casting about for a direction, or mining his old one. It’s as if the genius for melancholy folk-rock’s still there, but kind of fighting to express itself as it’s fogged by underproduction, and not-quite-killer tunes.

Some of the songs on Sings For You aren’t too memorable, and so lyrically obscure and sprawling that they don’t make the beeline to the heart that his best compositions could. In common with many demo-like batches, there’s also some sameness to the material and approaches that demands a good number of plays before the cuts stick out from each other. That said, however, after such repeated listening—if quite a bit more than some listeners might want to invest—the tunes do grow on you, as does insight into what seems to be a rather fragile, uncertain state of mind when Clark did these sessions.

A good number of the tracks are handicapped by rather slapdash backing, by musicians whose identities are unknown, with the exception of pianist Alex del Zoppo (from Los Angeles group Sweetwater). In particular, the drumming’s so indelicately over-busy that whoever’s in the seat makes oft-criticized Byrds stickman Michael Clarke seem like a virtuoso. Odd embellishments by calliope and Chamberlin strings (a keyboard similar to the Mellotron) add dabs of eeriness, but also a sense of mild experimentation without a firm goal in mind.

But there are substantial positives to these songs, most notably a yearning, questing undercurrent that runs through almost all the words and melodies, even if you’re rarely sure exactly what Gene’s on about. There are, of course, meditations on mysterious women who seem to be floating out of reach (“On Her Own”). Certainly there aren’t many celebrations of romances going well, if seldom falling into gloomy despondency (albeit “Yesterday, Am I Right” comes close, with its wail “what good is my life without you near”).

Some items show sides of the man to which we’re not accustomed. He strains, not too effectively, to hit some really high notes in “Past My Door.” “Down on the Pier” can’t help but recall Bob Dylan’s “4th Time Around” with its waltzing rhythm and vaguely surrealistic ruminations, and a melody similar enough to merit veto had it been considered for official release. The country-rock he’d already investigated in compositions like “Tried So Hard” (from his first solo LP) is heard just once, in one of the better cuts, “7:30 Mode,” whose six-minute string of images and punctuations of bluesy harmonica also bear a heavy Dylan influence.

Of the six tracks not sourced from the Sings For You acetate, the four solo acoustic performances also have mild to definite traces of Dylan (especially “On Tenth Street”), and have a bit of a generic Clark troubadour feel. Not all of them are previously unavailable in any form. Gene gifted a couple, “Till Today” and “Long Time,” to L.A. band the Rose Garden for use on their 1968 album, now reissued by Omnivore with numerous bonus cuts.

Considerably superior are the two full-band tracks that weren’t placed on the original Sings for You acetate. Blues-rock wasn’t Clark or the Byrds’ forte, but “Big City Girl” has a fairly convincing, jagged bluesy strut, as well as lyrics intimating things aren’t really going to work out with this independent-minded woman—a theme recurring in several of Gene’s songs from the period. The forceful “Doctor Doctor” almost verges on folk-rock/power pop, with haunting moaning vocal harmonies, a bashing chorus, cool curling guitar licks, and a more assured production than the other efforts on this collection. It’s the highlight of this interesting but erratic anthology, and maybe the only track that sounds like it could have been released in 1967 without getting re-recorded in a more polished state.

Note also that there’s yet more unreleased Clark from 1967 on the six-song, twelve-inch EP Back Street Mirror, on Entree. A few of these songs have come out on previous archival releases (sometimes in different forms), though three haven’t circulated. These are likewise interesting-but-not-quite-top-tier efforts, Gene getting into a blues-folky mood on “That’s What You Want,” and using unexpectedly poppy orchestration on “Yesterday, Am I Right.” (My full article on this album, including an interview with Clark biographer John Einarson, is online here.)

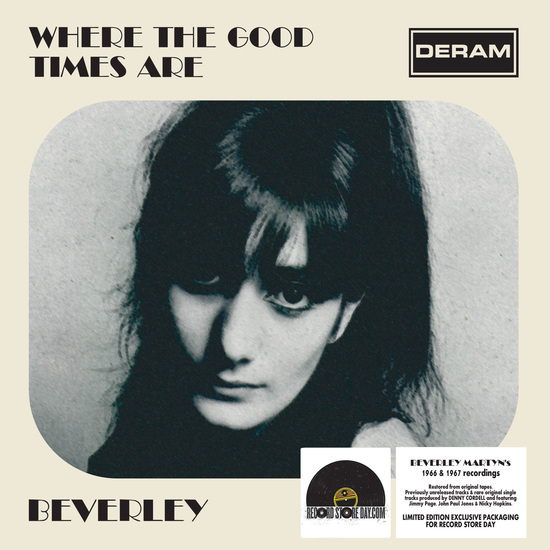

16. Beverley, Where the Good Times Are (Deram). Beverley’s better known as Beverley Martyn, the name she took after marrying and sometimes recording with John Martyn. Before that, she cut a couple obscure UK singles for Deram in 1966 and 1967, but didn’t release an album for the label. This Record Store Day release comes close to simulating the LP that might have been, adding a bunch of tracks (one without vocals) that were unissued at the time. All the material was produced by Denny Cordell, famous for working with the early Moody Blues, Move, Joe Cocker, and Procol Harum. The backup musicians included Jimmy Page, John Paul Jones, John Renbourn, Nicky Hopkins, and Alan White.

Although Beverley came from the folk world, and covers a couple Donovan songs here, this isn’t exactly folk-rock. It’s fairly interesting, reasonably gutsy pop-rock with more folk and blues than most British women-sung pop of the time had. There’s more potential than realization, but Beverley’s original compositions—which comprise half the tracks—are decent, reasonably forceful efforts. Her slightly pinched voice sometimes sounds like Melanie, though the American singer had yet to record and wouldn’t have been an influence on her.

Her own songs are the highlights of this disc, especially the rather haunting “Tomorrow Time.” Her stabs at blues are mediocre; “Happy New Year,” one of the cuts that was on her Deram singles, bears most interest as an early obscure Randy Newman composition; and though it looks at a glance like one of the Donovan songs was not recorded by Donovan himself (“Picking Up the Sunshine”), it’s actually a version of his “Bert’s Blues” with a different title. The highlights of this record make the LP of more than merely historical interest, but it’s not well served by the packaging, which has barely anything in the way of liner notes—a criticism that applies to some other Record Store Day releases of rarities, including the two others reviewed in this list.

17. God’s Children, Music Is the Answer: The Complete Collection (Minky). God’s Children put out just a couple obscure singles in the early 1970s (both included here), but they were a pretty interesting band with a notable pre-history. One of their three lead singers was Willie Garcia (aka Little Willie G.), who’d been the main vocalist for the finest pre-Santana Latino rock band, Thee Midniters. God’s Children were in some ways an early-’70s update of Thee Midniters’ eclectic blend of rock, soul, and some doo wop. They were a little more eclectic, however, also drawing from funk and gospel, and influences from a couple other notable multi-cultural bands ascending to superstardom, Santana and Sly & the Family Stone. “It Don’t Make No Difference” sounds quite a bit like the Sir Douglas Quintet, with a similar piercing organ.

This 14-track anthology is more promise than realized potential, especially as it had to be pieced together from their two singles from UNI (whose pop-oriented production did not play to their strengths or emphasize their strong original material); demos, a couple of which are instrumental backing tracks; and the rare (if good) solo single Little Willie G. issued in 1969. Still, the material’s fairly strong and diverse, and the blend unusual, even for those adventurous times. They’ve compared themselves to a Latino Fifth Dimension or a Three Dog Night with women singers, and there’s some justification to that. But they were in fact hipper than either of those groups, without getting the commercial songs needed to gain them a wide audience or even many issued discs.

18. Skip Spence, Andoaragain (Modern Harmonic ). At a time when expanded reissues of vintage albums are becoming a huge part of the catalog business, Skip Spence’s Oar seems like one of the most unlikely albums to get the multi-disc treatment. Yes, its haunted acid-folk (dabbed by more than a touch of acid casualty), with plenty of rootsy blues and country thrown into the mix, is now deservedly hailed as one of the finest obscurities of the psychedelic age. Recorded at the end of 1968, shortly after the ex-Moby Grape guitarist’s release from a mental hospital, it felt like a missive from a ghost who’d barely survived the indulgences of the Summer of Love, with feet in both the Haight-Ashbury and the Mississippi Delta.

But for all its deserved subsequent cult reputation, it sold barely anything when it was first issued in 1969. Even if the absurdly low sales figures (such as 600) sometimes reported might be lower than the actual total, it was certainly one of the most obscure major-label releases of the late ‘60s, rave Greil Marcus review in Rolling Stone notwithstanding. And the LP itself had such an off-the-cuff, rustic one-man-in-an-empty-room feel that it was difficult to imagine much was left over.

But we live in an age when nothing seems impossible, at least when it comes to poking around the vaults. The wittily titled Andoaragain presents no less than three CDs from the Oar sessions, with two entire discs of previously unreleased material. There’s even an outtake from the LP photo session on the cover.

Previous CD editions of Oar had unearthed ten outtakes, all included here as bonus tracks after the original album plays on disc one. In comparison to the dozen tracks on the finished LP, those outtakes were, as the British are fond of saying, “bitty” fragments. None were nearly as solidly constructed as the songs on the proper album, and none sounded apt to be as strong as the final contenders with more work. All of which raised alarm bells, when this much more extensive trawl through the vaults was announced, whether such an exercise was worthwhile. Might it even prove embarrassing to Spence, even half a century later?

Like many such raids of the lost psychedelic arks, it’s neither as marginal nor as revelatory as you might expect. If you’re rightly wary of CDs two and three being yet less listenable half- (or less than half-) finished tunes from the Oar sessions, the first thing to note is that more than half of these 36 (yes, 36) additional tracks are alternate versions of songs that made the final cut. That in itself ensures the majority are more listenable than the items that have already shown up as bonuses on previous reissues.

Alas, it also signifies that there aren’t any previously unheard songs on the order of “Weighted Down,” “Lawrence of Euphoria,” or “All Come to Meet Her”—or indeed, on the order of any of Oar’s compositions (save perhaps the LP’s meandering closer “Grey/Afro”). The “new” titles—of which there are nine (sometimes in multiple versions)—seem to be either made-up-on-the-spot ditties, bits that haven’t grown into germs of full-blown songs, or semi-jams, some with a more rock’n’roll feel than the Oar material (like, unsurprisingly, “I Want a Rock & Roll Band”).

Occasionally there’s a glimmer of the kind of odd wordplay distinguishing Oar’s fully realized compositions, like the disquieting “she has a body of 17, and a mind of 40” in “Fuzzy Heroine (Halo of Gold)”—the only “alternate” version here of one of the songs previously issued as a CD bonus track. Otherwise, the impression is often of a guy, to quote a lyric from “Dixie Peach Promenade,” who’s taken everything from A to Z. For all that, Spence sounds pretty normal and coherent on occasional brief spoken snippets from the outtakes, though of course that’s a pretty small sample size.

None of the numerous alternate versions are a match for the finished products. These indicate—as is often, maybe usually, the case no matter what the professionalism or state of mind of the artist—that considerable refinement went into the songwriting and arrangements before the tracks were completed, and that the cull of available Spencesongs was quite selective. Part of Oar’s peculiar spell is its apparent spontaneity and effortlessness, but the rather haphazard pool of recordings from which it emerged indicates considerable effort was put into molding it into a much more accessible end result.

But even if none of the alternate versions are on the level of the LP tracks, some of them are quite nice and worth hearing. Considering how bare-bones (certainly for a late-’60s psychedelic rock artist) the album’s production was, it might be hard to believe that some of these outtakes are yet sparer, though the essence of the words and music usually remain. An instrumental version of “War and Peace” doesn’t even have those words, yet has a spooky, affecting vibe when stripped of the vocals and psychedelic effects deployed on the LP rendition. The “basic” version of “Cripple Creek” doesn’t vary too much from the familiar arrangement, but has an engaging, slightly more pronounced country-folk feel.

Elsewhere, the brief, jokey rehearsal of “Weighted Down” doesn’t seem like an entirely serious attempt at this gravest of meditations, but at least it’s appreciably different from the LP take. The biggest surprise arrives when Skip briefly inserts part of the melody from Jefferson Airplane’s “She Has Funny Cars” into “All Come to Meet Her.” Spence, of course, was the drummer on their first album. But even though Jefferson Airplane Takes Off had only been recorded about two-and-a-half years earlier, that must have seemed like twenty years ago after all Skip had been through in the meantime, from Moby Grape’s first LP to the bad acid trip that helped land him out of the band and into Bellevue Hospital.

Of special note are no less than half a dozen alternates of “Diana.” That makes for quite a few to choose from, I know. But they’re usually invested with a particularly urgent eerieness, especially on the six-minute run-through that ends disc two, and even on the 12-string instrumental version. Such is his intensity that it seems like “Diana” must have been a real person, whether that was her name or not, as it’s not easy to fake such emotional anguish.

For all its magnificence, Oar wasn’t for everyone, even if it did eventually generate a tribute album with contributions from fans like Robert Plant, Beck, and Tom Waits. Exponentially more so, Andoaragain isn’t for everyone, or even every Oar fan. But even if I’m far less likely to be spinning the dozens of outtakes than the core album, I’m glad it’s out there. Heard in modified doses, it’s a bit like listening to a talented but wayward friend trying this and that as he sorts through the musical voices battling to be heard in his head. Sometimes he succeeds in winnowing them into something pleasing, sometimes not. But he seldom offends, and often intrigues. (A longer version of this review will appear in a future issue of Ugly Things.)

19. Various Artists, Gathered from Coincidence: The British Folk-Pop Sound of 1965-66 (Grapefruit). With the exception of Donovan, none of the top mid-’60s folk-rock innovators were from the UK. And really, with the exception of Donovan, no British acts of the period truly blended much of the best of folk and rock into a new and distinctive form. As the subtitle of this interesting three-CD comp indicates, what mid-’60s British folk-rock there was often took a milder form, blending folk and pop as much (or more) than mixing folk and rock. Folk, and American folk-rock, was felt more as an influence on pop and rock than it was actually combined with rock.

This 79-track set gets off to a literally ringing start with the one cut that could be classified as authentic classic folk-rock, the Searchers’ excellent cover of P.F. Sloan’s “Take Me For What I’m Worth.” But it’s more a historically interesting tour of folk’s absorption into British popular music (and occasional ventures of folkies into slightly pop-rockish sounds) in the mid-’60s. There are plenty of fine recordings; some that have their merits; and plenty of so-so or even subpar ones, significant mostly as a testament to the industry’s eagerness to jump on the bandwagon.

The best tracks, though necessary to provide something like a comprehensive overview of this retrospectively named mini-genre, are also the ones ‘60s rock fanatics are most likely to already own. The Hollies’ cover of Peter, Paul & Mary’s “Very Last Day” gets close to classic folk-rock; Manfred Mann’s “If You Gotta Go, Go Now” was one of the earliest hit (at least in the UK) rock versions of a Dylan song; and Marianne Faithfull’s hit “Come and Stay with Me” was nearly genre-defining folk-pop. Donovan’s “Catch the Wind,” of course, was his first hit, though he would have been better represented by something electric from the Sunshine Superman album.

Also here are some major acts’ satisfying ventures into folk-rock-ish material, like the Pretty Things’ “London Town,” Peter & Gordon’s “Morning’s Calling,” the Kinks’ “Wait Till the Summer Comes Along,” and the Zombies’ gorgeous “Don’t Go Away,” though the latter track (like quite a few on this anthology) is more folky than folk-pop or folk-rock. There are also some fine folky efforts by some of the era’s better non-star UK groups, like the Poets’ “I Love Her Still,” the Sorrows’ “Don’t Sing No Sad Songs for Me,” and the Fenmen’s “Rejected.” The last of these, of course, features future Pretty Things Wally Waller and Jon Povey, even if it’s as indebted to West Coast harmony pop as folk-rock, whose influence is mostly heard in the chiming guitar hook.

And there are some less essential actual hits that nonetheless need to be here to complete the picture, like the Silkie’s “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away,” the Seekers’ “The Carnival Is Over,” and Hedgehoppers Anonymous’ “It’s Good News Week.” A few artists who were more folkies than rockers did try to add touches of rock into their work, as you can hear on Davey Graham’s pretty good take on the Beatles’ “I’m Looking Through You,” and early work by Mick Softley, Meic Stevens, Jon-Mark, and Beverley (aka Beverley Martyn).

Whether or not you’re a folk-rock enthusiast, if you have a deep ‘60s collection, you’re likely most curious about the more obscure selections. While there are quite a few, these are—even casting aside questions as to how genuinely they blend folk, rock, and pop—pretty uneven, with an absence of lost gems. Some are unnecessary close copies of the originals, like Peter Nelson’s version of Tim Hardin’s “Don’t Make Promises.” Some are bad novelties, like Alan Klein’s “Age of Corruption,” a satire of “Eve of Destruction,” a hit that inspired more bad answer records than almost any other.

And there are future superstars briefly venturing into the style, like Marc Bolan on “Beyond the Risin’ Sun,” Olivia Newton-John (!) on the Jackie DeShannon-penned “Till You Say You’ll Be Mine,” and a pre-Moody Blues Justin Hayward on “Day Must Come” (whose orchestral pop-folk actually makes for one of the best obscurities). On “The Bells of Rhymney,” a young Murray Head even entered the foray.

Here and there, however, are sprinkled some pretty good outings known to few. The Beatmen’s “Now the Sun Has Gone” is a very good bittersweet, acoustic guitar-grounded ballad. The Caravelles (of “You Don’t Have to Be a Baby to Cry” fame) sing a fairly lavish Phil Spector-ish production of Canadian folkie Bruce Murdoch’s “Hey Mama You’ve Been on My Mind” (not to be confused with the early Dylan composition “Mama, You’ve Been on My Mind”). Sarah Jane’s “Listen People” is a decent cover of the Graham Gouldman-penned Herman’s Hermits hit, though like a lot of tracks here, it stretches the boundaries of what might be considered folk-pop, let alone folk-rock.