Hard as it is to believe, we’re one-fifth into the twenty-first century. Maybe even harder to believe, plenty of material continues to surface on rock reissues. Often these aren’t reissuing official recordings, but unearthing half-a-century-or-so-old items often not even suspected to exist. Most of the really fine LPs from the time have been re-released (sometimes several times), and virtually all of the really fine acts who recorded a good amount of fine music have been honored by compilations.

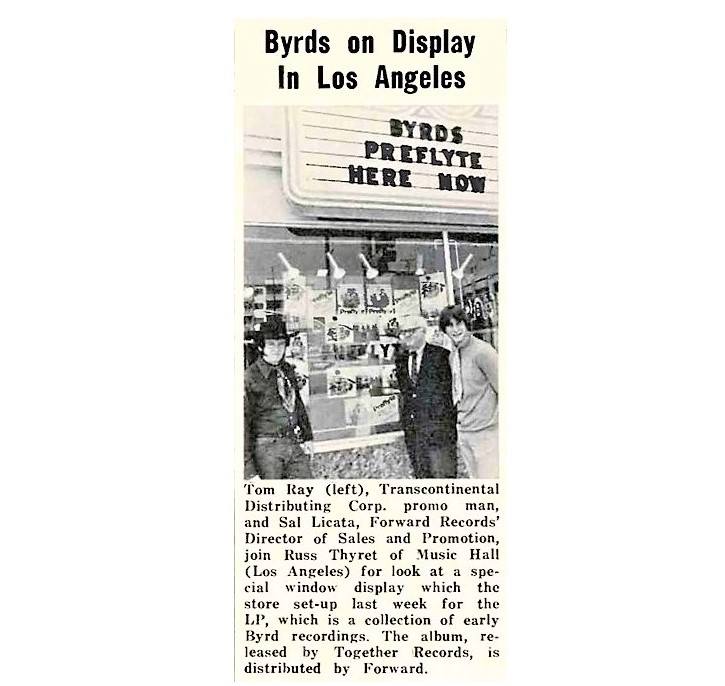

As I already have a lot of those, most of what I’m getting on reissues these days tends to be studio outtakes, live concerts, and radio recordings, often circulating for the first time anywhere. Otherwise they tend to be bulky boxes containing much or all of what a significant artist did in their entire career, or at least the peak (or one of the peaks) of it. Just one of my best-of picks from the 2019 litter is a straight album reissue, and even that album was barely distributed upon its original release.

So it’s boxes and vault rarities—which sometimes fill up boxes on their own—that dominate my best-of list. It just about made a round twenty in number, throwing in a couple 2018 releases I’d missed at the end. I heard a good number of other reissues, but these are the ones about which I got enthusiastic, or at least somewhat enthusiastic. Although the chart-topping winner has plenty of merit, I had more negative comments about the way the music was released than I ever expected to put into any review of a #1 pick.

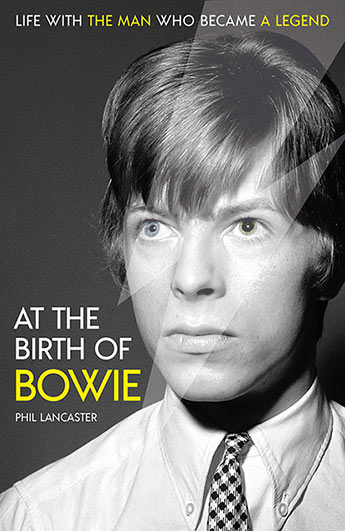

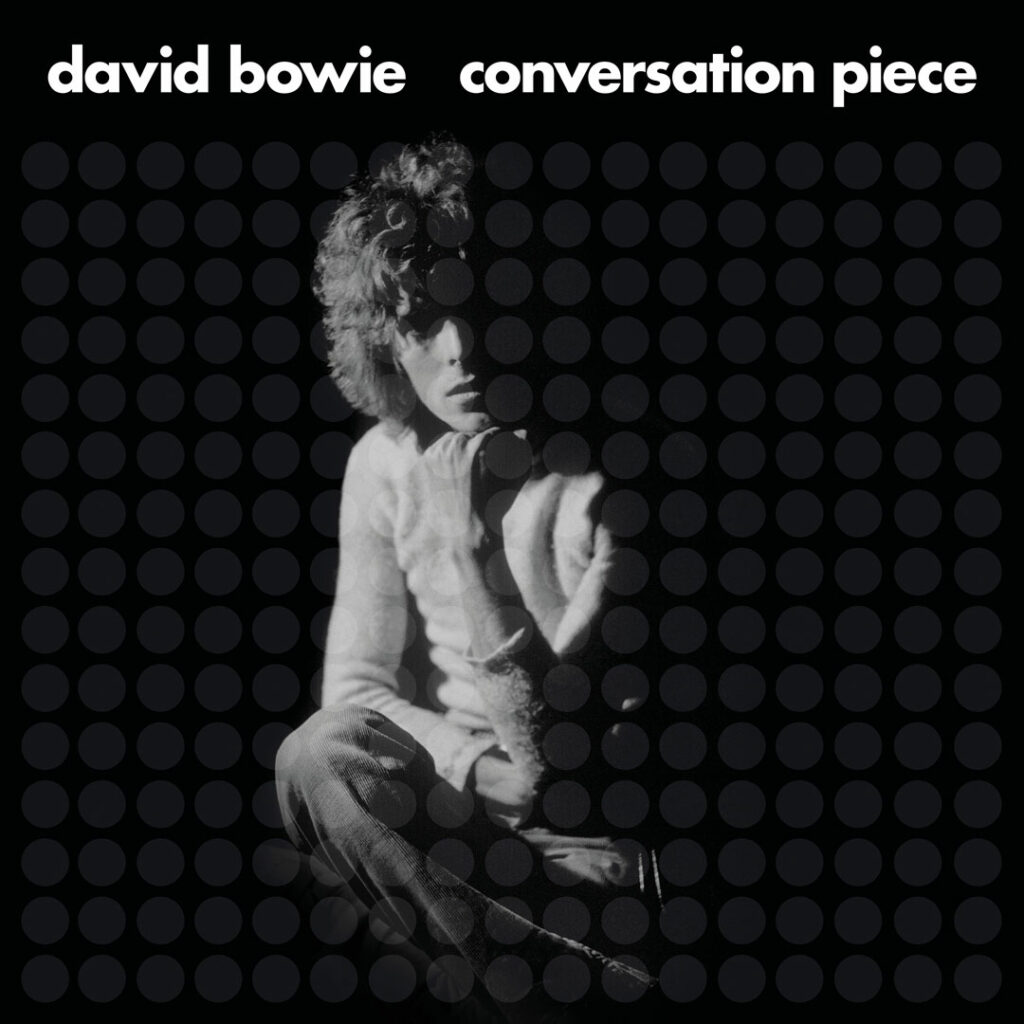

1. David Bowie, Conversation Piece (Parlophone). As a five-CD compilation of material Bowie recorded in 1968 and (more often) 1969, this box has great musical value. It’s not such great economic value for the kind of dedicated Bowie fans most likely to want it, since the majority has been previously released. Even most of the material unavailable before 2019 had been issued before this box came out in November. First I’ll focus on the enormous musical positives, and then get into the troubling part of how this stuff was dispensed to the marketplace.

The most significant disc by far is titled The ‘Mercury’ Demos. I’ve been touting these early-’69 demos (almost certainly done around late winter or early spring) as a major body of unreleased music since I first found it on bootleg (minus one song, though this LP has all ten) in the late 1980s. As I wrote on my blog a few years ago:

“Unusually, this captures Bowie at a point in his career where he was a folky, or at least folk-rocky, singer-songwriter. As hard as it might be to believe, he—with backing by second guitarist/harmony singer John Hutchinson—sounds something like a British Simon & Garfunkel here. The songs, of course, are quite different from those of Paul Simon even at this early stage in Bowie’s development, and include acoustic versions of highlights from his 1969 and 1970 releases like ‘Space Oddity’ (with a primitive Stylophone effect), ‘Conversation Piece,’ ‘Janine,’ ‘Letter to Hermione,’ and ‘An Occasional Dream,’ the last of which is one of the greatest unreleased Bowie performances (and most overlooked Bowie songs, period) of all.

Other songs aren’t as impressive, and some, particularly ‘When I’m Five’ and ‘Ching-A-Ling,’ are kiddie-like leftovers from his overly theatrical phase. But even the minor tunes include some neat oddities, like a cover of Lesley Duncan’s ‘Love Song’ (done slightly later by Elton John on Tumbleweed Connection) and the haunting ‘Lover to the Dawn,’ which never made it onto a Bowie release, though it evolved into a song that did, ‘Cygnet Committee.’ And you get to hear Bowie and Hutchinson unexpectedly segue into the chorus of ‘Hey Jude’ near the end of ‘Janine.’

Aside from being the only document of that brief period in which Bowie and Hutchinson worked as a duo, I find this of even greater importance for capturing what might have been the true personal Bowie—or at least as personal a Bowie as he could summon given his chameleonic nature. Sincerity is not a quality we usually associate with him, but if there was any time where he meant what he sang, instead of writing as a character (or writing about other characters), this might have been it.”

There you have my musical assessment. What specifically about this official release of the tapes, however? The good news is that this does definitely sound better than the numerous bootlegs of the material, all of which had a lo-fi, muffled, and sometimes wobbly sound. This isn’t super hi-fi, but it’s much clearer, whether they used a different better tape source, did a lot of sonic cleanup, or some combination of the two. Many Bowie fans have known about this stuff for a long time, but they’ll be pleased to have it in significantly more listenable form. This is the disc on the box that makes it an important release, and would have been #1 on its own if it had been issued as a standalone CD without the other material.

Another disc in the box of 1968-69 home demos is also quite valuable and interesting, if not nearly on the musical level of the Mercury demos. The best are eight songs (actually just six different ones, as there are three versions of “Space Oddity”) recorded in December 1968 and January 1969 on a Revox reel-to-reel tape recorder in Bowie’s London flat. If nothing else, these clear up something that’s always been uncertain to me: the exact source of the two demos of “Space Oddity” and “An Occasional Dream” that were bonus tracks on the 40th anniversary edition of 1969’s David Bowie/Space Oddity album. According to the liner notes for this package, they came from these sessions (and are not the fairly similar demo versions recorded about a couple months later in 1969, which have long been bootlegged). This also includes earlier versions of a few other songs that are on those slightly later demos (“Ching-a-Ling,” “Lover to the Dawn,” and “Life Is a Circus”), along with one that isn’t (“Let Me Sleep Beside You,” which Bowie had already recorded for Decca in September 1967).

On to the music itself: these are sparse, folky acoustic performances with Hutchinson on second guitar and backup (and occasional lead) vocals, and some Stylophone on “Space Oddity.” They show Bowie developing into a far more interesting and idiosyncratic singer-songwriter than he had been on his earlier, official 1964-68 studio recordings, especially on “Space Oddity” and “An Occasional Dream.” There is both a tender melodicism and a feeling that Bowie’s not only gotten more personally expressive, but is about as genuinely personal as he’d ever get, given his subsequent taste for genre-jumping and character-assuming.

The performances on the Mercury demos just a couple months later are a little bit less inhibited and more assured, and for that reason (along with the bonus of interesting lighthearted between-song banter), I’d give them the edge. These are still interesting to hear, though, and in pretty good quality considering the fairly primitive circumstances of the original recordings.

There are also fifteen Hutchinson-less 1968-69 demos (if any are from 1969, they’re probably from early in that year) of more historical than purely musical interest. Bowie wouldn’t put most of those songs on his studio releases, and while they show him fitfully developing a more mature, rockier singer-songwriter (and less annoyingly theatrical) style than what he’d done in his Decca son-of-Anthony Newley phase, the compositions aren’t that great or memorable. Exceptions are an early version of the 1970 B-side “Conversation Piece” and a different version of his kiddie tune “When I’m Five” that, relatively speaking, is far gutsier and more listenable.

The final three discs on the box are steadily less interesting, mostly because most of the tracks have long been available. One’s largely devoted to 1968-69 BBC sessions (all previously released) that offer worthwhile variations of late-‘60s studio recordings, with marginal bonuses of a couple mono mixes of 1969 studio tracks and an inferior alternate studio arrangement of “Space Oddity” when Hutchinson was still aboard. Disc four has his 1969 album David Bowie aka Man of Words, Man of Music aka Space Oddity, which as the “aka”s alone signify has been reissued more times than anyone cares to count, with bonus tracks of early mixes and the full length version of his Italian-language rendition of “Space Oddity.”

Disc five, the least essential, has a 2019 Tony Visconti mix of the album, with the original 45 versions of “Wild Eyed Boy From Freecloud” and “Ragazzo Solo, Ragazza Sala,” as “Space Oddity” was titled in Italian. The 120-page book of liner notes is pretty good, with detailed annotation and lots of rare photos, as well as some particularly interesting repros of period memos, press releases, gig posters, and newspaper clippings.

Now for my value-for-money rant. Most of the previously unissued tracks on this package were issued in three separate, expensive vinyl boxes earlier in 2019. That included two sets of demos on seven-inch singles that were about $35 each after tax, and the Mercury demos as a vinyl LP selling for $69.98 at my favored local independent store. These prices are extortionate. Yes, the Mercury demos LP comes in a big box reproducing the typed and handwritten lettering on the original tape box, with a photo of Bowie and Hutch, a couple contact sheets of more photos, and liner notes. That doesn’t justify charging triple or so the rate for the usual new vinyl album. And while the liner notes are pretty good, they’re on six stapled pages with small, faint type, and no illustrations.

Worse, at no time to my knowledge was it announced that all of the tracks on those expensive vinyl releases would be later made available on CD as part of the Conversation Piece box, and soon. And I get press releases from the label who put all these Bowie projects out. I certainly would have been willing to wait to save $150.

So the way these cuts were doled out checks all of my boxes of showing disrespect for the fans that have made such archive projects possible, and profitable. Overpriced packaging. No advance notice that the music on those overpriced vinyl sets would soon be made available in one place on a more reasonably affordable CD box. Only a dozen tracks on that five-CD box that were previously unavailable, some of which are not-so-interesting alternate mixes. And one disc almost wholly devoted to a 2019 remix of an album, which I find, like most remixes, unnecessary (and actually here, in the case of the remixed “Space Oddity,” notably inferior). Even if it was done by Bowie’s most important producer.

I honestly don’t know the expenses involved and profit margins for packages like this. But I do know that many fans would much prefer to buy this material all at once as a standard-priced CD, and not feel like they’ll risk being able to hear it at all if they don’t buy the expensive vinyl boxes as soon as they appear. I only hope that some of the money goes to John Hutchinson, as I think he can use it much more than the Bowie estate.

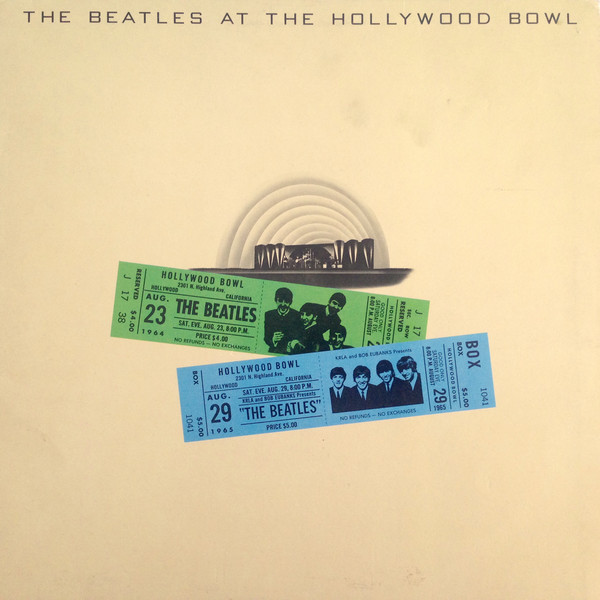

2. The Beatles, Abbey Road 50th Anniversary Edition (Apple/Universal). This would top this list based on the original 1969 Abbey Road album at the core of this four-disc box. But a reissue list, or at least my reissue lists, judge releases like this by what they add to the original, not by ballyhooed new mixes. In this case, this box falls short of the fiftieth anniversary box of The White Album, and maybe even of the fiftieth anniversary box of Sgt. Pepper. Sure it’s still worth getting for Beatles fans, but it’s overpriced. So was the Sgt. Pepper box, and arguably The White Album box, but this is more so.

The positives are mostly to be found in the two CDs of session outtakes. The compilers, however, faced a challenge as there weren’t nearly as many outtakes as there were for The White Album sessions; what outtakes were generated weren’t as interesting; and some of the best such outtakes were already used on Anthology 3. And in case you were hoping that some previously unheard original compositions might have been discovered, that’s not the case. In fact, just a couple of these (Paul McCartney’s long-bootlegged home demo of a song given to Mary Hopkin, “Goodbye,” and his demo of “Come and Get It,” made into a hit by Badfinger) were not released in a different form by the Beatles in 1969. All of the other tracks are alternate versions, including alternates of every Abbey Road song and both sides of the “Ballad of John and Yoko”/“Old Brown Shoe” single.

Alternate versions can be pretty interesting, as much of the White Album box demonstrated. I’m glad to hear them here, but nothing really blows me away. George Harrison’s solo demo of “Something”—not the same as the one on Anthology 3, as this has two piano parts in the mix—is the best of the batch. The differences among the other alternate versions are minor, and sometimes very minor. The version of the side two medley (here titled “The Long One”) differs in the edit and mix, not the performances. The take of “Something” that isolates the strings, and the “strings & brass only” one of “Golden Slumbers”/ “Carry That Weight,” are of primarily academic interest.

And the package is also missing some outtakes that have been documented (most thoroughly in Mark Lewisohn’s Beatles Recording Sessions) and sometimes even bootlegged. Most notable among the absentees is the different version of “Something” with a long, doom-laden piano-led instrumental tag, with a tune later recycled by John Lennon for “Remember” on Plastic Ono Band. This is even referred in the box’s book of liner notes, making its failure to appear here all the more irritating. Maybe the feeling was that multiple versions of alternate takes shouldn’t be used, though there were some on the White Album box, and no one minded to my knowledge.

To the displeasure of some readers and acquaintances, I’m generally unenthused about new mixes and blu-ray audio, which take up the other two discs. The same holds true here—there wasn’t anything wrong with the original, and I find the differences both minor and inconsequential. One consequence, however, can’t be ignored: it shoves the list price into the three figures. The package does include a 100-page book with plenty of interesting text and illustrations, but even this isn’t quite as good or big as the books with the White Album and Sgt. Pepper boxes. Don’t forget, too, that the Sgt. Pepper box came with a DVD of a twenty-fifth anniversary documentary. Maybe it’s unfair to chide a box for not having as much bonus material to draw from, but that does make the Abbey Road fiftieth anniversary edition less worthwhile than its counterparts.

3. Craig Smith/Maitreya Kali, Apache/Inca (Ugly Things). In the late 1960s and early 1970s, there were a good number of obscure, often privately pressed acid folk albums, where the performer (usually a solo artist) seemed lost between reality and fantasy. Most of them weren’t very good, and certainly not as good as the standard bearer for the genre, Skip Spence’s Oar. Apache/Inca, credited here to singer-songwriter Craig Smith and his alter ego Maitreya Kali, is an exception. It’s very good, and in some ways spookier even than Oar, which is saying something. The original double LP, which appeared in the early ‘70s, was also quite haphazardly assembled. It mixes well-produced Buffalo Springfield-meets-the-Monkees late-‘60s recordings by his group the Penny Arkade with later spare, haunting solo performances reflecting his descent into mental turmoil, even madness.

The later material, dating from when he adopted the name Maitreya Kali, is usually folky, acoustic, and swathed in reverb. The sentiments are a long way from the good-time folk-rock he’d delivered with the Penny Arkade. “Love and pain are the same,” he crooned on “Old Man,” echoing the similarly creepy sentiments in Charles Manson’s deranged songs of the late ‘60s, though with far greater melodicism and musical skill. On “Love Is Our Existence,” he gave his vocal such a tinny fishbowl effect that it was all but indecipherable; “Revelation” was hardly any easier to make out, but couldn’t quite bury a dynamite folk-rock riff, as well as some intriguing lyrics both glorifying and questioning the validity of Jesus, Krishna, Buddha, and other deities. Other songs were more straightforward, if exceptionally haunting, folk ballads. Yet they always gave the impression of a seeker questioning reality, and not quite finding satisfactory alternatives.

This CD marks the first official reissue of Apache/Inca, embellished by 32 pages of liner notes from Mike Stax. The original master tapes have disappeared, but this has been, to quote the liner notes, “restored and mastered…from the cleanest vinyl source available.” Although the juxtaposition of Matireya Kali and Penny Arkade tracks can be incongruous, those Penny Arkade cuts (none issued back in the late 1960s) are among the finest obscure Los Angeles folk-rock of the period. For a full Penny Arkade CD with all of the tracks by the group used on Apache/Inca and more, look for Sundazed’s Not the Freeze compilation. For more on Smith, check out Stax’s fine biography Swim Through the Darkness.

4. The Artwoods, Art’s Gallery (Top Sounds). Not to be confused with their 1966 album Art [no ‘s] Gallery, this is a collection of previously unreleased 1965-66 BBC performances by the British R&B band featuring singer Art Wood (older brother of Ron), drummer Keef Hartley, and a pre-Deep Purple Jon Lord. Since sixteen other BBC tracks were included on the three-CD set Steady Gettin’ It: The Complete Recordings 1964-67, you might wonder how essential another set of BBC cuts might be, especially for a hitless British Invasion band who were decent but not great. Maybe it’s not essential unless you’re a big Artwoods fan or a huge British Invasion fan in general. But it is highly worthwhile, for a few reasons.

First, just a couple of the songs (“She Knows What to Do” and “Smack Dab in the Middle”) are represented by BBC versions—completely different ones—on The Complete Recordings. Second, seven of the thirteen tracks weren’t done by the Artwoods on their studio releases. Third, the sound quality, while not brilliant as these are not the original broadcast tapes, is quite acceptable. And most importantly, these are for the most part really good slabs of mid-‘60s British R&B/rock, with a more prominent organ (by Lord) than most such outfits boasted. I don’t find Art Wood a great singer, but he doesn’t get in the way of the instrumentalists’ cool grooves.

And while a few of the rarities are average, there’s some really good stuff here that stands up to their best studio work—a dynamite organ-paced instrumental soul-jazz-rock version of “Comin’ Home Baby,” a jazzier instrumental in Les McCann’s “That Healin’ Feelin’,” and a certainly-good-enough workout on James Brown’s “Out of Sight.” While the BBC versions of songs also found on their studio releases might be less eye-catching, some of them are fine supplements to the studio takes, like a moody treatment of Lee Dorsey’s “Work, Work, Work” (“just a tad slower” than the studio track, accurately state the liner notes); the Bobby Blue Bland raveup “Don’t Cry No More”; and two peppy versions of their best song, “Oh My Love.” On the whole I find these significantly better than the numerous BBC tracks on The Complete Recordings—whose title is no longer accurate now that these additional radio tapes have surfaced.

The Artwoods were never going to be a top-tier British R&B act, owing both to Art Wood’s relative shortcomings as a singer and their near-absence of any original material. But does it matter so much when you can enjoy a collection like this over and over? I didn’t expect it to rate so high on this list, but that’s what it comes down to in the end.

5. The Yardbirds, Live and Rare (Repertoire). The Yardbirds released quite a bit of material in the five years they were active – about four or five albums’ worth, if spread among a wealth of LPs, singles, and EPs in several countries that would have been difficult to track down in total even back in 1968. Since then, however, their catalogue has multiplied several times over with archival live recordings, BBC sessions, outtakes, and even commercials. Even for fanatics, it’s hard to keep track of what’s come out where.

So a new five-disc box of Live and Rare cuts can understandably be greeted with some skepticism as to whether it has much, or anything, you don’t already have somewhere or other. It’s certainly likely to duplicate a good amount of stuff in your collection if you care enough about the Yardbirds to consider buying a five-CD rarities box in the first place.

That’s the case with Live and Rare, but it still has some vital things going for it that make it worth your attention whether you’re a completist or just want to start rounding out your Yardbirds library. Unlike some such anthologies, it has decent annotation, including overview notes by UT’s own Mike Stax (though the disc-by-disc liners are by veteran UK rock journalist Chris Welch). And if you want a kind of multi-disc best-of-the-rare, it’s a decent survey, taking in many of their better BBC/TV sessions and non-Five Live Yardbirds live recordings.

But to skip to the chase, the main reason for hardcore fans (and I’m one) to pick this up is the DVD, which has 21 songs spanning 1964-1968 with the Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, and Jimmy Page lineups (and even the Beck-Page one). Much of this has circulated unofficially or semi-officially for years, especially the March 1967 appearance on the German Beat! Beat! Beat! TV program. But here you have it in bulk, with quality likely to better (or certainly at least equal) other sources.

The big find is a windy, outdoor seven-song Paris performance from April 30, 1967 that hasn’t shown up anywhere else, at least to my knowledge. Here are the only live clips of “Mr. You’re a Better Man Than I,” “My Baby,” and the unlikely Dylan cover “Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I’ll Go Mine)” from anywhere, as well as the only Page-era one of “Heart Full of Soul.” Half a year after Beck’s departure, Page is in fine form. In all honesty—and this coming from someone who’s a fan of lead singer Keith Relf, not just the Yardbirds as a group—the same can’t be said of Relf, who sometimes wanders off-key or even off-mike, even as he prowls the stage with commanding enthusiasm.

Yet there are good-to-great features of all the other live clips, though Relf’s vocals sometimes aren’t a match for either the studio versions or the sheer volume of Beck and Page. The takes of “Louise” and “I Wish You Would” from British TV in July 1964 are the only surviving ones with Clapton, and the three songs from a June 1966 French TV spot the only ones of the Beck-Page lineup besides their Blow-Up bit. (Warning, however: this dates from the time Page was still on bass, not yet sharing lead guitar with Beck.)

Sadly, both numbers (“Shapes of Things” and “Train Kept A-Rollin’”) from the May 1966 NME Poll Winners Concert are incomplete, though you can hear the audio in its entirety on one of the CDs. It’s even sadder that the best of their live TV performances, on Shindig in 1965 with Beck, aren’t here, though most of you probably have or know how to see them anyway.

The three-song March 9, 1968 appearance on the French TV program Bouton Rouge is of special note not just as the last time they were filmed live, but also as the best evidence of the Jimmy Page lineup at its best. “Goodnight Sweet Josephine” (their final 45) might not have been much of a song, but they storm through “Train Kept A-Rollin’” and, more notably, offer a tour de force “Dazed and Confused,” complete with violin-bowed Page solo and Page-Relf harmonica raveup. And here Keith is in fine vocal form. It’s the best glimpse of what could have been had the group stayed together (or even managed to lay down “Dazed and Confused” in the studio), but wasn’t.

The audio for all the video can be found on the other discs, but the CDs have a lot more material, going back to seven tracks attributed to the 1964 National Jazz & Blues Festival. Know this, however: though these include a couple Chuck Berry numbers of which no other Yardbirds versions have circulated (“Little Queenie” and “Carol”), the first three songs (including “Queenie”) almost certainly don’t feature Relf on vocals. Expert listeners are pretty sure this is Mick O’Neill substituting for an ill Relf, and frankly he doesn’t come off too well, with a gruff delivery ill-suited for the band’s style.

Even if the CDs don’t offer a lot of surprises (or perhaps any, if you’ve kept up with everything in the by-now-massive Yardbirds oeuvre), certainly there are a lot of highlights, with even the lower lights never less than interesting. The radio broadcasts focus on some of the songs and versions less likely to make Yardbirds BBC collections, including storming versions of “I’m Not Talking” (two of that song, actually) and tunes that didn’t make their studio releases, like the melancholy folk lament “Hush-A-Bye” and the blues classics “Spoonful,” “Bottle Up and Go,” and “The Stumble.” The Page lineup usually came off better live than in the studio, and that’s amply represented by the two discs of 1967-68 recordings, including BBC versions of the two best songs from their waning days, “Think About It” and “Dazed and Confused.”

There’s a bit of the fill-in-the-blanks feel to the 1966 disc, most of which is given over to studio rarities, including their notorious Italian pop single; commercials for Great Shakes and Maclean’s toothpaste; and mono versions of “Happenings Ten Years Time Ago,” its B-side “Psycho Daisies,” the “Stroll On” cut from the Blow-Up soundtrack, and everything from Relf’s pair of solo singles (including the alternate version of “Shapes in My Mind” that starts with a horn instead of an organ). Like almost any multi-disc Yardbirds compilation of bits and pieces, however, it all goes to show that even at the margins of their recorded work, they were usually much better than most other bands were at their best. (This review previously appeared in Ugly Things magazine.)

6. The Searchers, When You Walk in the Room: The Complete Pye Recordings 1963-67 (Grapefruit). While the Searchers made some records here and there for fifteen years after the mid-’60s, their legacy rests firmly on the wealth of material they cut for Pye Records from 1963-67. This six-disc, standard CD-sized box is likely the last-word package on that body of work. There are stereo and mono versions of all five of their UK Pye LPs; sixteen bonus tracks culled from outtakes and French/German-language versions; and an entire CD of non-LP singles, which throws in the EP-only cut “The System.” Add a 36-page photo/memorabilia-jammed booklet with a thorough history by UK rock scholar David Wells, and what’s not to like?

Nothing of consequence as regards the way this was assembled, certainly. (Although hard-to-pleasers will note the absence of stereo versions of two songs from their first album, “Da Doo Ron Ron” and “Where Have All the Flowers Gone,” as sources don’t exist for those.) But though they were the best Liverpool group besides the Beatles, and at their finest one of the best early British Invasion outfits, they certainly didn’t boast the consistent high quality or songwriting talent of their finest rivals. In fact, their LPs were pretty patchy, as those hoping to unearth hidden gems might find to their disappointment.

The gap between their uniformly fine 1963-66 singles — most of them UK hits, and several of them fairly big US ones — and most of their LP cuts, to be brutal, is almost huge. There are a wealth of mediocre covers of American rock’n’roll standards that are not only way less memorable than the originals, but also quite a few leagues below the best ones by their peers. Compared to the Beatles’ knocked-out-of-the-park interpretations, their takes on “Money” and “Twist and Shout” (both from their 1963 debut Meet the Searchers) are anemic. That might be an unfairly high bar for anyone to match, but generally their LP tracks—as was standard before the Beatles started to change the rules in that regard—suffered from thin, rushed-sounding production, contrasting poorly with the generally fine and full treatment afforded their 45s.

The Searchers didn’t write anything on their first three LPs, and while cover-dependent albums were common at the onset of the British Invasion, their interpretations were frustratingly erratic. Many are simply unmemorable or unimaginative, and sometimes unwisely chosen attempts at massive familiar American hits like “Be My Baby” and “Stand By Me.” Aside from their surprisingly great raveup treatment of the Coasters’ “Ain’t That Just Like Me” (which gave them a small US hit, and destroys the Hollies’ tamer UK hit version of the same tune), they just weren’t cut out for the kind of ferocious covers many of their peers mastered. Some of them—”Farmer John,” “One of These Days,” “Tricky Dicky,” “Alright,” and “Hungry for Love” (which was a British hit for Johnny Kidd)—have an engaging nervous, hyper-tempo Merseybeat, but lack the dangerous edge of the more R&B-oriented bands that would soon threaten the whole Merseybeat movement.

If it seems like I’m down on the Searchers, let me hasten to clarify that’s not at all the case. I’m a big fan of their best stuff, and some of that’s on these spotty LPs. When they slowed down a bit for more measured, taut R&B covers spotlighting their fine vocal harmonies, they scored deserved pulled-for-the-US-market hits with the Coasters’ “Love Potion No. 9” and LaVern Baker’s “Bumble Bee.” When they branched into folk standards and near-folk-rock, they hit on a wistful sensitivity whose strength they might not have fully realized at the time. That’s heard to excellent effect on their fine, if sparely arranged, covers of “All My Sorrows,” “Four Strong Winds,” and Jackie DeShannon’s yearning “Each Time,” as well as the group-penned “Too Many Miles.”

Indeed, “Each Time” sounds like it might have been considered for a single, boasting as it does more sonic depth than most of their LP-only efforts. And while some of their British hit 45s weren’t on their UK albums, the singles that did find a place on them—”Sweets for My Sweet,” “Sugar and Spice,” “Don’t Throw Your Love Away,” “Take Me for What I’m Worth,” and above all “Needles and Pins”—amply illustrate just why the Beatles cited them and the Rolling Stones when a teenager asked the Fabs to name their favorite British groups on a June 5, 1964 Dutch TV program. They had gorgeous vocal harmonies; they had finely sculpted, if restrained, arrangements; and, above all, they had ringing guitars that anticipated one of folk-rock’s trademarks.

And those five albums were hardly all there was to the Searchers’ discography. The sixth disc—devoted solely to 26 non-LP tracks—is so strong that they no longer sound like a middling band who managed enough great and good songs to make a fine best-of. Suddenly, they sound like a near-major act—which, of course, they were, but not on the strength of their longplayers. All of the hit singles that didn’t find a way onto their UK albums are here—”Someday We’re Gonna Love Again,” “When You Walk in the Room,” “What Have They Done to the Rain,” “Goodbye My Love,” and their moody original “He’s Got No Love.” So are some just-about-as-fine low-charting UK entries, like their covers of Jagger-Richards’ “Take It or Leave It,” the Hollies’ “Have You Ever Loved Somebody,” and Bobby Darin’s “When I Get Home.”

Most notably, so are a clutch of generally fine B-sides mostly known only to Searchers fanatics, many of which gave them a chance to write their own material. The delicate folk ballad “‘Til I Met You,” the peppy “This Feeling Inside,” the Buddy Holly-meets-formative-folk-rock of “So Far Away,” and the uncommonly mordant, grim-and-bear-it “Don’t Hide It Away” (with equally uncommon jazzy piano solo) are all among their best work—which, when you’re talking about the Searchers, is very good indeed. As Searchers guitarist John McNally lamented to me when I interviewed him nearly twenty years ago, “If you’d had said, like Andrew Loog Oldham did to the Stones, ‘go and write some songs and don’t come out ‘til you’ve written ‘em’ to us, we’d have been a much better act.” Some momentum was lost on their final three, not-so-impressive singles (all from 1967), but these at least seal the “complete” in the box set’s title.

It could be that for most Searchers fans, a best-of or at most double CD are enough. But it’s unlikely any selection would corral all of anyone’s individual favorites, so the Pye box it is if you want to dig deep. And be aware that while it’s the complete Searchers at Pye, it’s not the complete ‘60s Searchers, as no less than four other compilations—Live at the Star-Club Hamburg, the pre-Pye 1963 demos The Iron Door Sessions, BBC Sessions, and Swedish Radio Sessions—offer a wealth of worthwhile radio, live, and demo recordings. (This review previously appeared in Ugly Things.)

7. Family, At the BBC (Madfish). Although they never quite broke into the rank of the top British bands of the late 1960s and early 1970s, Family were nevertheless fascinating during their five-year-or-so-run. They unpredictably mixed various shades of blues, funky jazz, pastoral folk, and even country into their sorta-prog rock, though without melodic hooks as memorable as another group with slightly similar eclectic blends, Traffic. Roger Chapman’s bleating vocals were never going to have the mass appeal of Stevie Winwood, but certainly projected a distinctive personality, even if some would find them an acquired taste. Family were also quite capable at matching their intricate studio arrangements in concert, as this mammoth eight-disc set proves.

Even given that Family were far more successful in the UK (where they had four Top Ten albums and three Top Twenty singles) than in the US (where they barely charted), it’s amazing how often they played on the BBC. This box features 95 tracks from no less than 20 different Beeb broadcasts, spanning November 1967 to May 1973. Many of them have come out on CD before, but twenty make their first appearance here. And a DVD presents nine performances from five different programs in 1969-1971, mostly in color.

The songs that will arouse most interest among hardcore Family fans are those that didn’t appear on their official studio releases. “Bring It On Home” isn’t the famous Sam Cooke soul hit, but the Willie Dixon song that Sonny Boy Williamson recorded at Chess. “I Sing ‘Em The Way I Feel,” issued by bluesman J.B. Lenoir on an obscure 1963 single, is an even greater testament to the depth of their blues collection. “Blow By Blow” is a six-minute jam with some similarity to “A Song for Me.” A 1973 concert-closing “Rockin’ Pneumonia and the Boogie Woogie Flu,” however, falls into the category of “must have been fun to play,” but hardly indicative of the band’s core strengths.

All of those tracks have appeared on previous Family archival releases, which makes the twenty that are available for the first time of special note. Of particular value are Top Gear sessions from November 1967 and April 1968 predating the release of their debut album Music from a Doll’s House, including not just previews of six songs from that LP, but also their beguiling 1967 non-LP debut psychedelic single, “Scene Through the Eyes of a Lens.” While the fidelity on these two sessions and some other early broadcasts are obviously “off-air,” they sound fine and perfectly listenable, the whole box benefiting from considerable sonic cleanup.

Two other sessions—five songs from Colour Me Pop in May 1969, and another five from the Bob Harris Show in October 1972—also make their first appearance here. Family remained respectable to the end, but it’s a fair bet that UT readers will find the earlier half or so of this box the best. That’s the stuff that captures both Chapman and Family at their most sinister and haunting.

Although Family worked their way through much of their catalog on these broadcasts, inevitably this means there are multiple versions of many tunes—five apiece of “The Weaver’s Answer” (one of their best songs) and “Processions,” in fact. In common with most BBC performances, they’re not so drastically different that they redefine the compositions, but have a good live feel at times looser and more spontaneous than the studio counterparts. As some of the BBC takes preceded the official vinyl versions, arrangements could be in the process of getting refined. The March 1969 rendition of “Holding the Compass,” for instance, is electric, though the one surfacing a year and a half later on their 1970 LP Anyway would be acoustic.

The DVD is not a superfluous throw-in; in fact, much of it’s spectacular. With the exception of the earliest clip (“Dim,” from March 1969), it’s in vivid color and looks great. True, the wildly gyrating blonde girl dancer and period solarization effects on the Top of the Pops “The Weaver’s Answer” are a little distracting, but very much in the spirit of period fun.

Gearheads will thrill to the sight on some numbers—seldom duplicated by other bands, as far as I know—of two double-necked guitars in the same lineup (combining standard electric six-strings, a twelve-string, and a bass into two instruments). While he was in the group, also cool were the unusual contributions of Poli Palmer, whose electric vibraphone and flute added exotic instruments rarely employed in rock music. Strictly speaking, the four songs from a 1970 appearance on Doing Their Thing don’t belong here as that was broadcast on ITV rather than the BBC, but no one’s complaining.

For all its bulk, Family at the BBC doesn’t include everything they did on radio and film. Twenty-one songs from eight separate 1967-72 broadcasts (all detailed in the liner notes) haven’t survived, or been found. There’s also some other Family footage, such as their spots on the German TV show Beat Club, and their appearance in Stamping Ground, the obscure concert documentary of the 1970 Kralingen Music Festival in Holland. And while the group worked their way through much of the material on their albums over the course of the broadcasts compiled on this box, of course the studio recordings remain more definitive—and numerous, with plenty of bonus tracks augmenting their LPs on various compilations.

But for serious Family fans, this is a worthwhile if hefty investment that’s a significant supplement to their primary body of work. Packaging-wise, it could hardly be bettered, with a bound-in 52-page hardback book of liner notes that include meticulous details on the sessions; a Family family [sic] tree; and plenty of photos, along with a repro poster of their September 15, 1969 concert at London’s Royal Festival Hall. It’s a testament to the live sound of the band that, as John Peel notes in his introduction to their January 1970 session, was “one group that I would travel continents to see.” (This review previously appeared in Ugly Things.)

8. Various Artists, Diggin’ in the Goldmine: Dutch Beat Nuggets: Original Artyfacts from the Dutch Beat Era and Beyond (Pseudonym). Astonishing in its size and scope for such a niche genre, this eight-CD box of 1965-70 Dutch rock surveys arguably the most productive ‘60s scene from a non-English speaking country. Nor does it even stick with the most well known tracks and acts, offering many rarities that had seldom or never been heard even by Dutch beat collectors, whether by the “big names” like the Outsiders or no-names who made just one or two 45s that are impossible to find.

As the box shows, derivative as many Dutch acts may have been of overseas rock trends (especially British Invasion bands), they also developed a distinctly regional sound that wasn’t mere imitation British R&B. The Dutch groups added a distinctively morose, sullenly rebellious attitude that carried a massive chip on its shoulder. Bluesy guitar and harmonica riffs were twisted into something strangely sinister, as was the English language, even if that might have had as much to do with writing in English as a second-language as deliberate lyricism.

While the box isn’t as strong or consistent as the two Nuggets boxes that are the kind of standard-bearers for the ‘60s garage/freakbeat genres, they document a vibrant scene that wasn’t just raw punk and freakbeat by the likes of the Outsiders, Les Baroques, and Q65, though it’s heavily represented. Acid folk, blue-eyed soul, guitar pop, hard rock, and other offshoots are also on board, testifying to the incredible productivity of a country that didn’t really get its rock into gear until 1965 or 1966.

Some standouts fall well outside the Dutch beat stereotype, like Nona’s weird folk “The Other Side of the Mountain”; Roek’s Family’s “Get Yourself a Ticket,” which is slightly risqué pop that’s almost like a more rock-oriented “Je T’Aime…Moi Non Plus”; and Phoenix’s very credible Hendrix tribute/emulation “Ode to Jimi Hendrix,” the last track on the box. Dream’s hard rock “Rebellion” has some killer organ and guitar. There’s breezy pop that owed more to Merseybeat than freakbeat by acts like the Golden Earrings (before their name change to Golden Earring).

The box is enhanced by a 204-page hardback book of photos, memorabilia, and liner notes by Mike Stax, editor and publisher of the top ‘60s rockzine, Ugly Things. Besides track-by-track descriptions, it even includes rarity values for the original discs on which the tracks appeared, some of which are in the several hundreds of Euros. There’s much more Dutch beat elsewhere by the best acts represented on this anthology, but this has a representative span of much of the best and rarest, without duplicating a lot of what’s available on the more high-profile reissues. You can read more about the box in my interview with Mike Stax for the pleasekillme.com site.

9. Fleetwood Mac, Before the Beginning: 1968-1970 Rare Live & Demo Sessions (Sony). This peculiar release has three CDs, and three and half hours, of recordings from the Peter Green era of Fleetwood Mac that hadn’t been officially released. Despite “demo” getting equal billing with “live sessions” in the subtitle, almost all of it’s live. Presumably all of it’s from 1968-1970, but despite fine and detailed liner notes in the 44-page booklet, the exact sources of the tracks aren’t cited. In fact, those are about the only details not specified in the liner notes, which otherwise comment at length about all of the songs and performances, as well as giving a good deal of historical context for the Peter Green period.

Gleaning what you can from the cloudy clues in the packaging, it seems like a good deal of the earlier material hails from a summer 1968 concert, or concerts, on their first US tour. A good deal of the later material seems to come from the US tour spanning December 1969 to February 1970. Only three tunes are represented by multiple versions (and then just twice each). The four tracks (there are only four) identified as demos are only referred to as “studio quality recordings” with little info, though they certainly sound like performances that have been bootlegged (in worse fidelity) on compilations of Fleetwood Mac BBC tracks. These and three of the live cuts on disc three are described in the notes as originating from 1968 “recordings done for different promotional shows,” one of the vaguest labels I’ve ever read applied to rarities. Also vague: a “horn-like harmonica player” is praised for contributions to a couple live numbers, but not identified, or even acknowledged as unknown.

According to the superdeluxeedition.com site, “the recently discovered recordings [for the collection] date from 1968 and 1970 and were discovered unlabeled in the US, so not much is known about them other than they have been authenticated by experts and approved for released by Fleetwood Mac.” It’s almost as if there’s a reason someone’s hiding or deliberately failing to disclose the origins of the material. Its the kind of thing associated with gray area releases, except that this was approved by the band (according to superdeluxeedition.com), “lets us re-live the power of the original Fleetwood Mac on stage with material personally selected by Peter Green” (according to the liner notes), has those lengthy in-depth liner notes, and has come out on a major label.

That long-winded explanation of why I can’t give you more precise source notes out of the way, the music is on the whole worthwhile, if (like all of the Peter Green-era catalog) uneven. The sound quality’s good, and the performances generally very good, avoiding the kind of too-long jams heard on some of the other early live Fleetwood Mac that has made it into official or unofficial circulation. Overall I prefer it to the most well known such material, that being several albums worth of early 1970 Boston recordings that have been packaged under numerous different titles. There’s a mix of some of their most famous songs (“Oh Well (Part 1,” “Rattlesnake Shake,” “The Green Manalishi,” “Albatross”), quite a bit of the straight blues at the base of their early repertoire, some of the mediocre rock’n’roll oldies they could never resist inserting into their sets, and some songs that didn’t make it onto the three late-‘60s LPs with Green. The distance between their very best stuff and their lesser output was wider with early Fleetwood Mac than with almost any other major rock group, but the best of this batch is very fine, and most of the rest at least satisfactory.

Highlights include a nine-minute version of B.B. King’s “Worried Dream,” which doesn’t get dull and features some magnificent slow-sad Green blues riffs. The performance of “Albatross,” not much different from the hit single, is very good too, and the cover of Otis Rush’s “Homework” sensational (I think the latter might be from a French TV program). It’s good to have a longer, live take on one of Green’s best obscure originals, “I Loved Another Woman,” though this and a few other cuts have some periodic faint vocals. “Before the Beginning,” another of Green’s best not-so-famous compositions, is rendered with despondent eloquence, though it ends rather abruptly. If you want real long variations, “Shake Your Money Maker” is eight minutes, Danny Kirwan’s “Coming Your Way” eleven minutes, “The Green Manalishi” almost twelve, and “Rattlesnake Shake” thirteen (though there are much longer versions of “Rattlesnake Shake” around). Too bad, though, that the first part of “I Need Your Love So Bad” is missing.

Although they’re a minor part of the set percentage-wise, the tracks tagged as demos (though I believe they’re from the BBC) are some of the best. In fact, one of them’s the very best cut – a version of Willie Dixon’s “You Need Love,” originally recorded by Muddy Waters in the early 1960s, and the basis for key parts of Led Zeppelin’s “Whole Lotta Love.” It’s a terrific version, with dual guitar riffing, a jittery propulsive beat, and one of Peter Green’s best vocals, alternately commanding and playful. And it sounds much clearer here than it has on bootlegs. The demo (again, I think, BBC) cover of T-Bone Walker’s “Mean Old World” is a really good blues shuffle, and the other two demo/perhaps BBC numbers are solid enough as well. “You Need Love” alone justifies this set’s release—and if you’ve had enough of such clichéd boasts in reviews by writers who get some stuff free (though I did pay $14.99 for a used copy), you’ll be relieved to know this three-CD set was selling for a reasonable $18.98 at my local large indie store.

As a final note, fewer bands have been as heavily documented on above-ground and underground discs as early Fleetwood Mac, considering they only put out three proper LPs with Green. In my collection, I count, besides those three LPs, an official two-CD set of BBC broadcasts; about eight or nine official CDs’ worth of studio outtakes; seven official CDs or so worth of live recordings; one unofficial CD of BBC recordings; and seven CDs of unofficial live recordings. There’s even more out there. And maybe even more will come out officially, though for the time being, it’s hard to imagine too many fans craving additional helpings.

10. Manfred Mann, Radio Days Vol. 1-4 (East Central One Limited). Since Manfred Mann were one of the more popular British bands of the ‘60s, and still had sizable (if more sporadic) success going into the ‘70s, it’s not a surprise they recorded plenty of BBC sessions. The sheer bulk of this new series still takes you aback. The eight discs span 1964-1973, and take in not just many hits, but also lots of lesser-known B-sides and album tracks. There are also a good number of covers, and even some originals, they never put out on their studio releases. And the third volume digs beyond the BBC vaults to unearth more than a CD’s worth of soundtrack recordings and commercial jingles, throwing in some outtakes and a non-LP 45. It’s maximum Manfred.

Manfred himself is the only guy to appear on all four sets, and while it’s probably not the intention of this series, cumulatively they illustrate how his group changed more than almost any other over the course of that decade. And not just via their numerous personnel changes, in which Mann was the only constant presence, and the outfit’s very name changed from Manfred Mann to Manfred Mann Chapter Three and Manfred Mann’s Earth Band. Each of the four comps might almost have been recorded by different bands, so drastic were his gear shifts. Fleetwood Mac might have been the only comparably popular outfit who changed so much in their first ten years, to the point where they and the Manfreds were almost unrecognizable from when they started.

Each volume covers a distinct phase of Manfred Mann, volume one documenting the Paul Jones era. Even then Manfred Mann were kind of several bands in one, handling jazzy R&B and classy pop-rock with ease, and taking odd detours into other areas with less success. There’s no “Doo Wah Diddy Diddy” here, as sadly several sessions spanning late 1963 to late 1964 don’t survive. Their other 1964-66 hits are represented, along with some standout LP/EP outings like “Groovin’,” “What Am I To Do,” “Look Away,” “Machines,” and “The One in the Middle.” In one of the many brief interview segments (from the original broadcasts) interspersed throughout the CDs, Jones discusses how he wrote “The One in the Middle” for the Yardbirds, who turned it down as “Keith Relf said that’s not my sort of personality.” There are two versions of a half dozen numbers, including a cool “Sha La La” where they throw in a deliberately subdued chorus that builds back to a full-throated finale.

As (in line with the great majority of BBC sessions from the era) the radio arrangements don’t vary enormously from the studio versions, the most curiosity will be aroused by the songs that aren’t otherwise available, particularly three penned by Paul Jones, though these are in some ways the most disappointing. Jones wrote some good tunes, but his compositions “That’s the Way I Feel” and “It Took a Little While” are by-numbers R&B workouts; “You Better Be Sure” is a bit livelier, and might have made acceptable filler on one of the later LPs he cut with the Manfreds. Weirder, though not good, is their unlikely novelty cover of the Hollywood Argyles’ “Long Hair, Unsquare Dude Called Jack” (co-written by Kim Fowley), dating from the brief period when Jack Bruce was in the group.

Volume two spotlights the Mike d’Abo era, in which Jones’s replacement sang a series of big UK hits from 1966-69, though only “The Mighty Quinn” also hit it big in the States. All of those are here (sometimes twice), along with some strong originals that many singles-buyers never heard, like “Each and Every Day” and “Cubist Town.” They also took the opportunity to play some covers that never made it onto this version’s ‘60s vinyl, like “Mohair Sam,” “Wang Dang Doodle,” “Hound Dog,” “The Letter,” “Fever,” “Abraham, Martin & John,” “She’s a Woman,” and “I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man,” the last of which was the only song performed by both the Jones and the d’Abo lineups. Note that some of the versions of the hits use previously recorded backing tracks – sometimes taken from the official release — with vocal and instrumental overdubs. That might have saved time back in the day, but makes them less interesting than many another BBC session, whether by the Manfreds and countless other acts.

As the BBC-exclusive covers wouldn’t have been highlights of their records, the big attractions are a few originals that didn’t see the light of day at the time, some of which are rather different to what the d’Abo lineup were usually doing. The d’Abo-composed “Handbags and Gladrags” became far more famous via covers by Chris Farlowe and, more notably, Rod Stewart. Its failure to make a Mann LP (or even single) is vexing, and though d’Abo put it on his 1970 debut solo album, a fine full Manfred Mann BBC version is a highlight of this collection.

Also notable are two good Mike Hugg compositions the Manfreds never placed on their official discs, the pensive “So Long” (not the same as their cover of Randy Newman’s “So Long, Dad,” which is also here) and melodic ballad “Clair” (sung by Hugg himself, with bassist Klaus Voormann on flute). D’Abo’s to the fore on the pleasantly poppy “Oh What a Day” (also resurfacing on his 1970 LP, though Manfred Mann didn’t release a version). He previewed his solo career with his ballad “The Last Goodbye,” on which he sings and plays piano without backup from the rest of the group.

There was a significant gap between the almost bubblegum pop of some of their late-‘60s hits (a la “Ha! Ha! Said the Clown”) and the more serious work on some of their LPs of the time. That disappeared when Mann and Hugg reorganized the band as Manfred Mann Chapter Three, whose work occupies the third volume. Arguably they got too serious, their records offering a sort of turgid early progressive rock with pop/R&B speckles, albeit in an oft-intriguingly gritty way that could verge on the grimy. Some of it almost sounds like Dr. John gone prog, though Hugg isn’t in the same league as a vocalist.

This has versions of a few of the songs from their pair of LPs on both the BBC and Swedish radio, as well as enough rarities to confuse discographers for years to come. Hugg’s “Breakdown” (from the 1970 Swedish broadcast) isn’t available elsewhere, as far as I can tell. Neither is the go-go-flavored instrumental “Bluesy Susie,” a live version of which plays behind a fairly entertaining interview with Manfred’s wife (“my wedding night was spent going with a boyfriend to see Manfred play”). There are also different 45 versions of “Happy Being Me” and “Devil Woman”; mono demo versions of “Konekuf” and “Time” that are different from the ones on the first Chapter Three LP; three tracks from Chapter Three’s unreleased third album (the burbling circular riffs of “So Sorry Please,” recorded July 1970, vaguely anticipating some of the synthesizer riffs on 1971’s Who’s Next); and a song they contributed to the soundtrack of the B-movie Swedish Fly Girls.

And that’s just disc one of the third volume. Disc two has their pretty snazzy 1969-70 jingles for Michelin, Maxwell House, and ski fitness, as well as background music for a 1968 BBC play. Most of the CD, however, is devoted to their soundtrack to the 1969 sexploitation movie Venus in Furs. The film had no relation to the Velvet Underground classic, and neither did Mann and Hugg’s music, which was an eerie mix of avant-garde horror and downbeat jazz. There are too many repeated motifs, and the sound too lo-fi, to make this something you’ll spin often. But in a way it’s the most fascinating section of this whole series, uncovering a side of Manfred Mann’s music unlike most of the other work in his voluminous catalog.

Mann overturned his personnel, and his sound, yet again in the early ‘70s with Manfred Mann’s Earth Band. Although he’d ultimately return to the top of the charts under this billing, their 1970-73 BBC sessions comprise the fourth and least interesting volume of this series. At least as determinedly prog-rock as Chapter Three, it wasn’t as eccentric, and pretty unlike Manfred’s ‘60s work, though there were links to the past in the choice of covers, particularly Randy Newman’s “Living Without You” and Bob Dylan’s “Get Your Rocks Off.” Dylan’s “Father of Day, Father of Night” gets a couple extended workouts (its studio counterpart would be one of the Earth Band’s most heavily played early-‘70s cuts on FM radio), and “Mighty Quinn” is revisited a couple times too. Leadbelly’s “Big Betty” had actually been recorded (as “Black Betty”), but not released, by the d’Abo lineup, and “Dealer” was a revamp of an LP track (“Dealer, Dealer”) from the d’Abo days.

It could be that prog-heads find volume four of this series the best of the lot, and have the least use for the Paul Jones days – and that British Beat fans feel exactly the opposite. You’d need to have very broad taste to like all four volumes more or less equally. But as they’ve been released separately, that’s not an issue if you want to give one or more a pass. The sound quality is usually good-to-excellent, and though some off-air recordings and soundtracks are not up to usual release standard, these are detailed as such in Mann biographer Greg Russo’s extensive liner notes. (This review previously appeared in Ugly Things.)

11. John Renbourn, Unpentangled: The Sixties Albums (Cherry Tree). He was one of the finest British folk guitarists, but John Renbourn was overshadowed by both his band and the other guitar player in that band. With Bert Jansch, he gave Pentangle the best acoustic guitar team in the country. But his own records weren’t as exciting or groundbreaking as his group’s. Nor were his own records as exciting as Jansch’s, since he wasn’t quite as creative a guitarist, and more decisively not as good a singer or songwriter. Despite his unquestioned virtuosity and eclectic mastery of folk and blues styles, his best contributions were as part of a unit, not as the focus of a spotlight.

That doesn’t mean his ‘60s work outside Pentangle wasn’t worthwhile. And while none of the six albums on this box set are that hard to get elsewhere, it’s handy to have all of them in one place, with a 24-page illustrated booklet of historical liner notes. Each of the albums is housed in a sleeve replicating the original front and back covers, and all but one has bonus material, though not so much that it’s an automatic acquisition for Renbourn fans.

The heart of the CD-sized box is in the three solo albums: the 1966 self-titled debut, the follow-up Another Monday (from later in ’66), and the tongue-twistingly titled Sir John Alot of Merrie Englandes Musyk Thyng & Ye Grene Knyghte, issued in 1968 almost simultaneously with Pentangle’s debut LP. There’s also 1966’s Bert and John, which isn’t so much a dry run for Pentangle as a kind of capstone for Jansch and Renbourn’s pure folk era. Filling out the set are the two albums he did with expatriate American singer Dorris Henderson (1966’s There You Go and 1967’s Watch the Stars), which were sought-after rarities for many years, but made easily available on CD quite some time ago.

That’s quite a productive three-year run, considering he was also busy cementing folk-rock-pop stardom of sorts with Pentangle from 1967 onward. If these LPs weren’t on the level of Pentangle or Jansch’s, they have their pleasures, if fairly modest ones. The first two solo outings make for highly agreeable low-key, cool-out listening as he fluidly ambles between folk, blues, and various combinations of the two. Another Monday holds additional interest for the presence of a pre-Pentangle Jacqui McShee on low-profile vocals for a few tracks. If Renbourn’s singing was pretty faceless compared to Jansch or McShee, and not even quite as imbued with character as adequate British folk singers like Davy Graham, it doesn’t drag things down either.

Sir John Alot (as everyone refers to it for convenience) finds him branching out a bit, if not hugely, with some ventures into medieval-flavored music. There’s also some modest backing from other musicians, including hand drums by Pentangle’s Terry Cox, though it stops well short of the more-or-less folk-rock Pentangle themselves were generating at the same time. Mostly instrumental, Bert and John might have been taken as the ultimate British folk guitar summit meeting at the time, and was certainly appreciated by some rock musicians, Jimmy Page likely among them.

Renbourn takes a more secondary role on Henderson’s records, but he’s not an incidental accompanist. His guitar work is arguably more interesting than the vocals, which are okay but not up to the standard of McShee’s, to take an obvious comparison. The sole bonus cut to Watch the Stars, however, is an interesting oddity on a couple grounds. Her cover of “Message to Pretty” on a non-LP 1967 single, if indeed Renbourn is playing on it (the liners have no specific comments about the personnel), is the only time this set gets into pure electric folk-rock, done fairly well in this instance. It must also be one of the few Love covers by British artists of the time. Was it perhaps even the first to make it onto disc?

Other bonus cuts include a couple alternate versions from Sir John Alot; a song apiece from Jansch’s It Don’t Bother Me and Jack Orion albums (as Renbourn played on those tracks); and outtakes from John Renbourn, including the blues “Can’t Keep from Crying” and Jackson C. Frank’s “Blues Run the Game.” Renbourn went on to make many more albums, but these are his most notable ones outside Pentangle, and worth attention by both Pentangle completists and ‘60s British folk fans in general. (This review originally appeared in Ugly Things.)

12. Bob Dylan, Travelin’ Thru, 1967-1969: The Bootleg Series Vol. 15 (Sony Legacy). This might be stating the obvious, but this three-CD set would rank higher if I was more of a Dylan fan, or even more of a fan of this era of Dylan. Basically it focuses on John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline outtakes, with four tracks he performed with Earl Scruggs in 1970 for a Scruggs documentary. Which means the years in this package’s title should really have been 1967-1970, but no refunds are likely if you complain about the inaccuracy.

The highlights are the alternate takes of seven John Wesley Harding songs. While overall they’re not terribly different from the ones used on this quickly recorded LP, sometimes they’re a tad rockier than the ones selected, especially on a much faster “I Pity the Poor Immigrant.” Conversely, the alternate “As I Went Out One Morning” has a much slower, more irregular beat, and isn’t as good as the official version, but is at least different. Never having liked Nashville Skyline much, I wasn’t too interested in the alternates for that LP, the exception being “Take 2” of “Lay Lady Lay.” Though hardly inadequate, it’s inferior to the hit single in every way, particularly as Kenneth Buttrey had yet to play his cowbell and bongo percussion. Technically speaking, it’s not previously unreleased, as it was available “as a digital download with iTunes pre-orders of Together Through Life.”

Almost twenty Dylan-Johnny Cash duets from February 1969, many of them long bootlegged, take up about half the collection. It’s nice to have these in better sound quality, including a few tracks (like “Wanted Man”) that haven’t shown up on bootlegs I’ve seen. But while the rockabilly-cum-country-rock treatments are fun to hear, they still sound rushed and ragged, with Cash’s vocals and songs far more to the foreground than Dylan’s. Filling out the set are the audio from a few songs Dylan did on Cash’s TV show in 1969; a couple Self-Portrait outtakes from May 1969; and the folky, and marginally interesting, Scruggs-Dylan collaborations. The annotation’s decent (though not exhaustive), but it’s one of the less essential installments in Dylan’s Bootleg Series, even as it diligently documents the leftovers from his Nashville country-rock phase.

The Self-Portrait outtake of “Folsom Prison Blues,” by the way, starts accelerating like an out-of-control locomotive near the end. It’s worth reviving Paul Cable’s observation on this cut in his book Bob Dylan: His Unreleased Recordings: “All Dylan can find to do with it is speed it up to a ludicrous rate as the end of the song approaches. If this was not the musicians playing a joke on him it must have been Dylan deciding he wanted to get this whole Nashville bit out of the way as soon as possible.”

13. Julie Driscoll, Brian Auger & the Trinity, This Wheel’s on Fire: The Lost Broadcasts (Vogon). There are no liner notes, or annotation as to when and where these tracks were recorded, on this gray area-looking release (nice color cover photo, though). That diminishes its value somewhat. But if you can cope with the absence of context, it’s a solid collection of late-‘60s-sounding radio and/or TV broadcasts, with pretty good sound that never has lo-fi bootleg quality. Besides featuring this British soul-rock/jazz/slightly psych act’s sole big hit, “This Wheel’s on Fire,” it also has some of their better known songs (a cover of David Ackles’s “The Road to Cairo,” “Save Me,” “A Kind of Love-In,” “Why Am I Treated So Bad”) and less traveled items like “Shadows of You” (a really swinging treatment that’s the disc’s highlight) and “I’m Going Back Home.” There’s also a song from Driscoll’s 1969 solo album, “A New Awakening” (no details about whether this version was cut with Auger, natch). Also present are some instrumentals spotlighting Auger’s organ (again, no info on whether these were done with the Trinity), including an almost unrecognizable arrangement of “A Day in the Life.” I find Auger’s organ more impressive than Driscoll’s singing, but their combination was unusual and interesting, if not destined to last considering their individual ambitions.

Also out this year on the London Calling label is a less impressive collection of a dozen Driscoll/Auger/Trinity live/TV recordings, Live on Air 1967-68. A problem is that they didn’t vary their repertoire too much for these performances, which include three versions of “Save Me,” two of “Season of the Witch,” two of “Tramp,” and two of “Red Beans and Rice.” At least it has an orchestrated cover of Nina Simone’s/the Animals’ “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood” that’s not found on their studio releases. It also has basic liner notes that at least give dates and locations for all of the tracks, though on the whole it’s not as impressive or adventurous in its material and execution as The Lost Broadcasts.

14. Tim Buckley, Live at the Electric Theatre Company Chicago, 1968 (Manifesto). Can you have too much previously unreleased live Tim Buckley? Not if you’re as much of a fan like I am, but even I have to concede some of those archive recordings aren’t for everyone, or even for frequent listening by fans. This double CD of live recordings from May 1968 falls into this category, as indeed does much of his posthumous live discography, which now include about a dozen discs’ worth. When you add on a few CDs of studio outtakes, there’s now way more posthumously issued stuff in Buckley’s catalog than what he managed to put out while he was alive—and he was fairly prolific in generating official albums when he was alive.

This isn’t everyone’s opinion, but I find most of Buckley’s live tapes markedly inferior to his studio output. He really did benefit from good production and full arrangements, which fortunately he often had. Outside the studio his songs, particularly on his more acoustic-oriented sets, were more bare-bones, and tended much more to sound like each other. That’s true of these performances, on which he’s backed only by Carter C.C. Collins on congas and an unidentified bass player. And like plenty of artists in concert, he often went on for too long.

So what’s this doing on this list, if near the bottom? His voice was so good it’s always good to hear it, even if it’s often more interesting here than the material. The songs include a good number of pieces he didn’t put on his studio albums, among them the largely instrumental “Look Out Blues” and, more interestingly, “The Father Song,” though that was heard in the obscure film Changes. Among the covers are Johnny Cash’s “Big River,” which he somehow stretches to almost eight minutes in a nearly unrecognizable interpretation. Much more satisfying is Fred Neil’s “Dolphins,” sung and played well here, and the definite highlight of the set. Add good liner notes with comments by Buckley songwriting collaborator Larry Beckett and sideman Lee Underwood, and there’s enough here to make this worthwhile for Buckley collectors, though it’s not a place to start even in his posthumous catalog.

15. Janis Joplin, The 1969 Transmissions (Leftfield Media). No big surprises here on what looks like a gray area release, as it’s not on Sony, which handles Joplin’s solo catalog. This 76-minute CD simply presents good-sounding live performances from Amsterdam on April 1, 1969, and the Texas International Pop Festival on August 30 of the same year. A note on the back says this is from FM broadcasts, and while I’m not sure about that, the fidelity’s very good, about up to official release quality. It’s not much different from official live material that’s come out from other Joplin performances from that year, and doesn’t have any big surprises in the set list. But her singing’s good and the backup decent (though not as inspired, if more polished, than Big Brother & the Holding Company). Plenty of her favorites are here, sometimes in multiple versions, like “Summertime,” “Combination of the Two,” “Ball and Chain,” “Piece of My Heart,” and “Try (Just a Little Bit Harder).” There’s more from Amsterdam than Texas, the Amsterdam set getting the edge. A good supplement to your Joplin collection if you’re a big fan, though not absolutely vital.

16. Various Artists, Land of 1000 Dances: The Rampart Records 58th Anniversary Complete Singles Collection (Minky). Where do you list a four-CD box set in which just one of the discs is really good, and only about three-quarters of that one disc at that? Here, I guess. Rampart Records was one of several imprints run by Eddie Davis. It specialized for the most part in the kind of soul-pop-rock-Latin hybrids generated by numerous East Los Angeles acts in the 1960s and early ‘70s, most of them by Latino artists (as well as a few African-American ones). Spanning the singles issued on Rampart from 1961 to 1968, the first two CDs are kind of so-so. The two actual hits (Cannibal & the Headhunters’ “Land of 1000 Dances” and the Blendells’ “La, La, La, La, La”) are by far the best tracks.

Yet, at least relatively speaking, most of disc three catches fire, at least for the first fourteen of its eighteen tracks. Featuring 1968-72 singles, none by well known names, these are really fine soul-pop-Latin confections. Sometimes they have a gauzy production that helps make them sound about five years older than they actually were, but that’s part of what makes them cool. Even the cover versions—of “Evil Ways” and Bobbie Gentry’s “Mississippi Delta” by the Village Callers, and “Crystal Blue Persuasion” by the Invincibles—are worth hearing. You wouldn’t think Tommy James’s “Crystal Blue Persuasion” a logical choice for a soul harmony group cover, but the Invincibles pull it off very convincingly and well. There’s a dreamy production to some of the sweet romantic tunes that’s unlike most of the other soul of the era, and some Latin-rock toughness to the more uptempo arrangements. The Hummingbird 4’s 1972 instrumental “Cho Cho San” is guaranteed to hit the spot for anyone who liked El Chicano’s somewhat similar hit “Viva Tirado.”

Unfortunately, the last four songs on CD three, and most of CD four (which has 1976-1991 recordings), are kind of terrible, with a lot of space for mediocre disco. The value’s enhanced by a good book of detailed liner notes (most by the late Don Waller) and fine photos, and if CD three was a standalone disc that cut off the four late-‘70s disco numbers, it would have made the top ten. It’s not, so it’s kind of in the honorable mention/just-sneaked-into-the-bottom part here.

17. Booker T. & the MG’s, The Complete Stax Singles Vol. 1 (1962-1967) (Real Gone). The best early Booker T. & the MG’s singles, like “Green Onions,” “Soul Dressing,” and “Hip Hug-Her,” tend to make it onto their best-of compilations. They’re also quite a bit better than most of their other singles, whether tracks from the A-sides and B-sides. Still, it’s neat to have everything from their first five years of 45s on one 29-track CD. The playing’s always sharp and often stellar, even if some of the material is run-of-the-mill R&B. There are also some good cuts that aren’t well known, like their moody-verging-on-spooky interpretation of the oft-covered “Summertime” and the delicately minor-keyed “Winter Snow,” one of those rare Christmas-affiliated discs that wholly avoids sappiness. I don’t have too much more to say about this collection, but there’s plenty about their early years in the 16-page booklet.

18. Jimi Hendrix, Songs for Groovy Children: The Fillmore East Concerts (Legacy). Back in 1970, six songs from Hendrix’s January 1, 1970 show at the Fillmore East comprised the Band of Gypsys album. Since then, additional material from all four of the sets he did at the Fillmore East on December 31, 1969 and January 1, 1970—with Billy Cox on bass and Buddy Miles on drums—has come out on an assortment of subsequent releases, and sometimes only on concert film, or in edited versions. This five-CD box presents, for the first time, everything from all four of the sets. Seven of the tracks haven’t been available anywhere. So for these reasons alone, it’s an historic document.

But what about the listening experience? Opinions on Hendrix’s catalog vary strongly, and one school feels this more R&B-oriented, post-Experience approach with African-American musicians is what he should have followed, or even been following all along. Mine is that this trio wasn’t nearly as good as the Experience with Mitch Mitchell and Noel Redding. They don’t do the Experience-era songs as well, and the more recent compositions by Hendrix weren’t as good as his earlier ones. And despite the skill of the players, plenty of the tunes meander or go on too long.

As this is Hendrix (with Buddy Miles taking vocals on a few songs), this is still worth hearing. “Machine Gun” alone, heard in three separate versions, validates this era, even if none of his other newer compositions were up to that epic. Billy Cox’s liner notes are interesting, and the booklet has plenty of cool photos. But I can’t say I’ll pull this out for nearly as much listening as my favorite Hendrix recordings, accounting for its low slot on this list.

Getting honorable mentions, as well as fulfilling the all-important task of padding this list into a round number of twenty, are two albums that were released in 2018, but which I didn’t get to hear until 2019:

1. David Bowie, The Lost Sessions (2018, Leftfield Media). While this double CD is almost certainly an unauthorized release, that hasn’t kept it from being sold online through the most mainstream commercial outlets, or in fact from being stocked by a public library in my area. Nonetheless, it’s a useful supplement to the official Bowie at the Beeb compilation, gathering 1967-71 radio sessions (as well as a couple stray outtakes, a brief 1966 interview, and a 1972 TV appearance) that didn’t make it onto that two-CD collection. There’s nothing in the way of songs unavailable in any form elsewhere, except the unexceptional 1970 studio outtake “Tired of My Life.” But there are a good number of performances of relatively obscure items from his catalogue, like “Little Bombardier,” “When I Live My Dream,” “Width of a Circle,” and “Amsterdam.” The sound’s usually pretty good, but only fair on the eight tracks from February 5, 1970. Other strikes against it: five other tracks from that February 5, 1970 broadcast have long been available on bootleg, but are not present here. And the liner notes are almost nonexistent, although at least the dates and sources of the original broadcasts are listed.

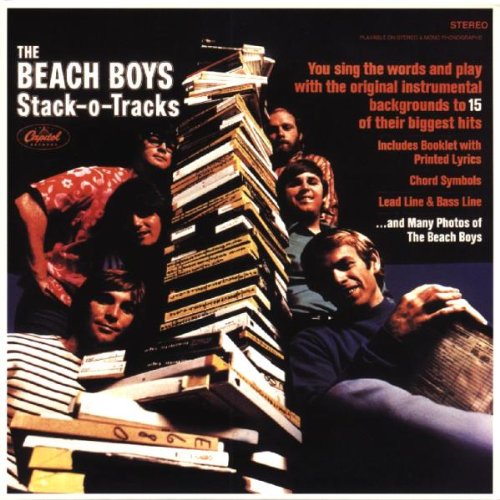

2. The Beach Boys, Wake the World: The Friends Sessions & I Can Hear Music: The 20/20 Sessions (2018, iTunes). It’s hard to say whether these things qualify as “albums” these days, since they’re only commercially available as downloads from iTunes. Still, they do add up to three CDs of outtakes from late-‘60s Beach Boys LPs, issued just in time to extend their copyright, a la some other iTunes-only releases by big acts. Maybe they should be considered as two reissues, but I’m combining them into one review here as the batch came out all at once, and almost everything was recorded pretty close to each other.

I’m not nearly as big a fan of Friends or 20/20 (or for that matter any of their post-Smile recordings) as some other Beach Boys cultists are. Here we have leftovers and works-in-progress from LPs that weren’t among their best, or even particularly great. The modest hit singles from these albums—“I Can Hear Music,” “Do It Again,” and “Friends”—are still by far the most memorable tracks. Some of the covers are really ill-suited for the group, whether tunes that ended up coming out on the albums like “Bluebirds Over the Mountain” or “Cottonfields,” or weird choices that didn’t (“My Little Red Book”). Like the 1967 Beach Boys outtakes that came out recently, a lot of these are fragments, or have a backing track/incomplete feeling, like the almost grim instrumental version of Buffalo Springfield’s “Rock and Roll Woman,” though original material dominates.

So what’s the good news? It’s still almost always nice to hear their harmonies, which still sound identifiably Beach Boys and like no other group, even when their material had changed enormously from just two or three years before these sessions. The arrangements and melodies might not be a match for that classic era either, but they’re often eccentric enough to keep your interest. They frequently hit a weird zone between the almost experimental and a desire to be accessible that just can’t be suppressed. Even some of the incomplete-sounding compositions are considerably attractive, above all “Been Too Long” (also known as “Can’t Wait Too Long”). It sounds like a nice hook in search of some more lyrics to fill out verses, or a chorus in search of the rest of the song. So you can file this in the “good to have” section if you’re a big Beach Boys fan, with the caution that it’s even more peripheral than many such outtake collections are.