I’ll be teaching a course on the Doors for the first time at the end of this month, and spent a lot of time preparing the material over the last few months. I’ve been a big Doors fan for more than forty years, but of course as I got my class together, I’ve thought a lot more about the group recently than I have for a while.

There’s been an enormous amount written about the Doors. It’s hard to believe there was a time, before the best-selling Jim Morrison biography No One Here Gets Out Alive came out in 1980, that there was no substantial book about them. Still, there are a few aspects of their work that aren’t discussed much. I’ll be going over a half dozen of them here.

1. The bass player(s). Even many casual rock fans know the Doors were unusual in not, with few exceptions, using a bass player onstage. Keyboardist Ray Manzarek is particularly noted for playing the bass parts on a Fender Rhodes Piano bass, simultaneously playing the upper register melodies on a Vox Continental organ.

Doug Lubahn’s book about the Doors, which includes a section specifically detailing his bass lines on the Doors tracks on which he played.

It’s not so well known that the Doors usually used an electric bassist on their recordings, though except for the first album (on which Wrecking Crew stalwart Larry Knechtel played on a few tracks), they were properly credited on the original LPs. Doug Lubahn, who plays on most or some of Strange Days, Waiting for the Sun, and The Soft Parade, handled the instrument more than anyone else. But they used a few others too, including Harvey Brooks on The Soft Parade (who’d played in the Electric Flag and on some of Bob Dylan’s mid-’60s sessions); Jerry Scheff on L.A. Woman (most noted for playing in Elvis Presley’s band); Lonnie Mack (on Morrison Hotel);, and, least famously, Ray Neopolitan, who plays on most of Morrison Hotel, though not much else is known about him.

If the quartet lineup—really a trio, instrumentally, Jim Morrison rarely playing anything—worked so well in concert, why was it almost always altered in the studio? There’s a pretty big difference between hearing something live and on a record, and they, producer Paul Rothchild, and Elektra Records were likely conscious that some more depth and oomph were needed. And the session bassists worked pretty well, whether playing on their own or kind of doubling/reinforcing Manzarek’s lines. Here are just a few of the memorable bass lines on Doors records:

That part near the end of “Take It As It Comes” where all the instruments dramatically drop out except bass and drums (Knechtel);

The opening riff of “You’re Lost Little Girl” (Lubahn);

The opening riff of “My Eyes Have Seen You” (Lubahn);

The part right before the final, shouted verse of “The Unknown Soldier,” introducing by a single declarative, loopy bass note (Kerry Magness, of the group Bodine, who only played on this one Doors track);

The fuzz bass on “Five to One” (Lubahn);

The throbbing bottom on the opening instrumental section to “L.A. Woman” (Scheff);

The ominous line underpinning the intro to “Riders on the Storm” (Scheff).

There are plenty of others. In fact, most of the tracks on Doors albums have a session bassist except for the self-titled debut, and even that has Knechtel playing on four of the eleven songs.

I’d go as far as to say it would have been a good idea for the Doors to have a full-time bass player, though it’s been reported that when they were first getting their sound together, they tried a few bassists and found the sound too full. Doug Lubahn would have been the best candidate, as he fit in with them well and was already recording for Elektra as part of the Rothchild-produced group Clear Light.

In fact, in his obscure memoir My Days with the Doors and Other Stories, Lubahn says Rothchild asked Doug if he’d consider joining the Doors as a full fifth partner in 1967. Lubahn, apparently without regret, turned him down as he wanted to stay in Clear Light, who ended up doing just one LP before splitting. Lubahn does acknowledge that when he brought up the subject with Rothchild twenty years later, the producer denied it ever happened.

Whatever took place, the Doors’ records sound great — in part because they used session bassists. Which leads to the next point:

2. The Doors were better in the studio than they were in concert. That’s nothing to be ashamed of — many and perhaps most bands sound better on their finished studio product than they do on live tapes. And at their best, the Doors were pretty good live. I do think the gap between their live and studio sound is bigger than it is for the usual top act, in part because they used bass players on their records. And the dynamic range and sonic balance of Doors records is usually pretty phenomenal, with engineer (and, on L.A. Woman, co-producer with the other Doors) Bruce Botnick deserving credit as well as Rothchild. Of course like countless acts they were sometimes able to use overdubs and effects that weren’t possible onstage, like Ray Manzarek’s use of the Marxophone on “Alabama Song,” his weaving of both organ and piano parts on “The Crystal Ship,” and the rain and thunder on “Riders on the Storm.”

That lets them off pretty easy, but there are some less flattering issues that can be brought up as well. For me at least, their live recordings—and I’m too young to have seen them in concert, so I’m going from the many official and unofficial taped shows in circulation—sometimes suffered in a few crucial respects:

Frequent insertions of dissonant poetry/music pieces, sometimes as medleys with actual songs with which they didn’t jibe too well. I’m not a big fan of the legendary “The Celebration of the Lizard” epic, but obviously it meant a lot to the Doors, or at least to Morrison, as they often performed small-to-big chunks of it. Sometimes the juxtaposition of a grating poem to a classic tune would be jarring, like when they preceded “Light My Fire” with that screeching “Wake up! Run to the mirror in the bathroom look” section. The medley of “Texas Radio & The Big Beat” and “Love Me Two Times” wasn’t as displeasing, but nor was it entirely logical.

A sense that they weren’t taking themselves too seriously. This comes through much more strongly on their 1969-70 tapes than the pre-1969 ones (which are much fewer in number, especially if you want decent fidelity). You don’t have to hear specialized archive releases or bootlegs to find this; it characterizes much of the official 1970 double LP Absolutely Live, where there’s sometimes a looseness that verges on sloppiness, and a jovial tone at odds with the serious poetic lyrics. Lester Bangs pointed this out back in 1976 in his chapter on the Doors in the first edition of The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll: “Morrison was by turns painfully and wryly aware of his own absurdity, and you can hear his humor in the between-song banter (“Dead cat in a top hat…thinks he’s an aristocrat…That’s crap”) on [the intro to “Break on Through”] on Absolutely Live.”

That’s why I think their tapes of shows at San Francisco’s Matrix tapes in March 1967 (two CDs of which have been officially issued) are easily their best live recordings, despite not-quite-optimum fidelity. “Light My Fire” was still three months away from becoming a hit, and they’re not yet jaded. They’re still hungry, and play things pretty straight. Even their second-best set of live recordings—two shows in Stockholm in September 1968, which have yet to see official release (possibly because of somewhat imperfect sound)—are more earnest and straightahead, without the toying with their own compositions you hear on the many official CDs of 1969 and 1970 concerts.

Mediocre blues/R&B/early rock’n’roll covers. The Doors did a lot of non-originals live that they didn’t put on their studio LPs. Which brings us to the next point:

3. The Doors were not particularly good at blues/R&B/soul. There were only three covers on Doors albums, all of which worked fairly well in their own way: Weill-Brecht’s “Alabama Song” and two blues classics, “Back Door Man” (written by Willie Dixon and originally recorded by Howlin’ Wolf) and John Lee Hooker’s “Crawling King Snake.” (With Ray Manzarek on vocals, they also put a little-commented-upon version of Dixon’s “(You Need Meat) Don’t Go No Further,” first recorded by Muddy Waters, on a B-side.) They did a lot more in concert, as was hinted at by 1970 even if you didn’t go to Doors shows, since they put a couple on Absolutely Live.

Archival releases and bootlegs have unleashed a lot more into circulation, including but not limited to “Money,” B.B. King’s “Rock Me,” Lee Dorsey’s “Get Out of My Life, Woman,” “Mystery Train,” “Heartbreak Hotel,” Slim Harpo’s “I’m a King Bee,” Chuck Berry’s “Carol,” Robert Johnson’s “Crossroads,” and “Little Red Rooster.” Back on the first live tape that survives (from May 1966 at the London Fog, recently excavated and released), they even do “Baby Please Don’t Go,” “I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man,” Little Richard’s “Lucille,” and Wilson Pickett’s “Don’t Fight It.”

I’m of two minds about the availability of all this surplus. On the one hand, you want live/archive releases/bootlegs to have material you can’t hear in an act’s common discography. The Doors have plenty of that, including not only the ones listed in the preceding paragraph, but also occasional non-blues covers like an extended instrumental version of “Summertime,” as well as some originals (usually half-baked-sounding) that didn’t make it onto their standard releases.

On the other, they just weren’t that good at these blues/R&B/soul/early rock’n’roll classics. Not nearly as good as, say, the Rolling Stones, one of their chief early inspirations, or some of the other best blues-oriented British Invasion bands, like Them, the Animals, and the Yardbirds. Or the Beatles, who weren’t nearly as blues/R&B-oriented, but did some great covers of songs in that style, “Money” being merely one of the most famous examples.

Some other great groups, it should be stated, weren’t great blues/R&B interpreters, like the Who. Just because you aren’t great at that one thing doesn’t mean you’re not great. But the Doors, unlike some other top bands, weren’t great at both covers and their own songs.

The Doors genuinely loved this music. But their interpretations were relatively perfunctory, sloppy, and unimaginative, often verging on the sluggish. Morrison tended to give in to some of his worst vocal mannerisms on these, such as affected yelps and macho growls and screams. It doesn’t bother me too much, but the live Matrix 1967 version of “Crawling King Snake,” predating its release on L.A. Woman by about four years, has some of the most abominable harmonica playing (presumably by Morrison) you’ll hear anywhere, though it fades away after the instrumental introduction.

There was just one R&B cover on their live recordings that was really good, despite their numerous attempts. The Matrix 1967 arrangement of “Who Do You Love” is lean, taut, and not too much like the Bo Diddley original. Compared to his usual blues interpretations, Morrison’s singing is effectively restrained; Robby Krieger’s slide guitar is superb; and the way the organ, drums, and guitars crash together and accelerate at the end is great. But it’s an exception that proves a general rule, in my view.

Had the Doors tried to make it as a straight blues/R&B band—or even, like some of their British Invasion heroes, a blues/R&B-oriented rock band—they never would have made it. The predominance of such material in their early sets was probably demanded/expected when they were unknowns who needed to play at least some familiar, danceable songs to club audiences. Their undistinguished efforts in this regard seem to have caused some other bands to dismiss them as hopeless no-contenders, and even make Rothchild and Elektra president Jac Holzman wary of getting involved with the Doors until they heard their far more impressive original material. Of which there was a lot, leading to the next point:

4. Were there any other top bands whose debut album was so clearly their best? I can’t think of any. The Doors were both blessed and cursed by their early productivity. Blessed because when they creamed off the best for The Doors, they had not just arguably the best debut album of all time, but one of the best albums of all time. Cursed because they couldn’t match that debut, even though they had a lot of fine music left.

Even for great groups that start off with a great album, usually that doesn’t happen. They don’t use up their best material; they write new material that’s good or even better, and stretches into new directions. That happened with the Beatles after Please Please Me, and the Who after My Generation. It happened with the Rolling Stones after their self-titled debut, though in part that’s because Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, who’d barely written anything by the time of their first album, quickly matured into a great songwriting team.

The Doors, unusually, seem to have written two to three albums’ worth of songs by the time their first LP was released. It’s only become apparent with the passage of time, and the availability of numerous archive releases, how many of their post-debut album compositions were actually written way before the sessions for their second LP (Strange Days, released September 1967). Seven of the ten songs from that record had been performed onstage by March 1967 at the latest, as half a dozen are on the Matrix tapes.

When I got this bootleg of March 1967 Matrix tapes as an 18-year-old in 1980, I was fascinated to hear early performances of numerous songs the Doors had yet to record in their famous studio versions.

(As an aside, those tapes are a reminder of the days when acts would perform quality original material in concert that hadn’t yet been released on their official albums. That would be uncommon in subsequent decades, in part because of fears, whether overblown or legitimate, that the songs would be bootlegged/broadcast/circulated before their proper unveiling on commercial discs. As an unfortunate consequence, many live performances haven’t been as interesting as they could have been had artists used them to introduce/refine new material.)

It’s known that some of the as-yet-unreleased songs on the Matrix tapes had been written and performed for quite some time. “Moonlight Drive,” the song Jim Morrison sang to Ray Manzarek on Venice Beach when they decided to form a band in summer 1965, was on their batch of half a dozen September 2, 1965 demos (and also recorded in an early version on an outtake from The Doors), as was “My Eyes Have Seen You.” “Strange Days,” to the surprise of even avid Doors fanatics like myself, is on the May 1966 London Fog tape that was released a couple years ago.

So when it came to the Strange Days album, you had a group of songs that were strong, but not quite as strong overall as those that had already been selected for The Doors. Whether because of Jim Morrison’s increasingly erratic behavior/indulgences and/or other reasons, they found it hard to maintain their quantity and the consistency of their quality, and kept dipping back into their early pool of songs when the well was sinking. On their third album (Waiting for the Sun), they plucked a couple other numbers from their September 1965 demo, “Summer’s Almost Gone” (also performed at the Matrix in March 1967) and “Hello I Love You.”

Even as late as Morrison Hotel, they retrieved “Indian Summer,” which like “Moonlight Drive” had been cut in a different version as an outtake for The Doors. Another big surprise from the May 1966 London Fog tape was an early live version of “You Make Me Real,” which took almost four years to appear on Morrison Hotel. Even on L.A. Woman, “Cars Hiss By My Window” has been reported to have been worked up from lyrics dating back to notebooks Morrison kept in Venice Beach in the mid-’60s.

Of course, many and maybe most rock artists sometimes reach back into their past, sometimes way back. The Beatles revived one of the earliest Lennon-McCartney compositions, “One After 909” (which they’d recorded but not released back in early 1963), in January 1969 for the Get Back sessions/Let It Be album. They took another song they’d considered recording, but not released, back in early 1963, “What Goes On,” when they needed to fill out Rubber Soul two and a half years later. The Beach Boys reworked “Thinkin’ About You Baby,” which Brian Wilson and Mike Love had penned for singer Sharon Marie back in 1964, into “Darlin’” in late 1967, and got a pretty big hit with it. There are numerous other examples.

But there aren’t many other examples of a band of comparable significance to the Doors using so much material that couldn’t fit onto their first album. They had enough, indeed, to make The Doors a double LP. But it wouldn’t have had the relentless knockout punch of the single disc, and double LPs in rock were rare back in late 1966, let alone double LPs that were also debuts (the Mothers of Invention’s Freak Out being a very notable and unusual exception).

Does that mean that the Doors’ career was a disappointment after their first album, and that none of their subsequent songs were on the level of the best from that LP? Of course not. But their trajectory was not one of explosive artistic growth through a sustained peak. It might have contributed to a sense of letdown that led some critics, like Lester Bangs, to view the band, kind of unfairly, as having slid into less relevance/hipness. Or at least find, as Lillian Roxon wrote in the late ‘60s her entry on the Doors in her Rock Encyclopedia (the first serious rock reference book), that “the second album was a repeat, a lesser repeat, of the first.”

The best of their final album with Morrison, L.A. Woman, indicates they just possibly might have been able to recharge themselves with both exciting fresh material and an interesting exploration of new directions had their lead singer lived. Which leads to the speculation:

5. What would the Doors have done if Morrison hadn’t died? Or at least lived long enough to be on one more album?

It’s an impossible question to answer, of course. Even if he’d lived, it’s possible he would not have recorded with the Doors again. Maybe he would have stayed in Paris and never returned to the US, in part to avoid a prison sentence he was appealing for profanity and public exposure at a March 1969 concert in Miami, though the other Doors could have recorded with him in France. There’s also speculation that he was tired of music and pop stardom, and wanted to discontinue his musical career in favor of writing poetry/prose and perhaps working in film—again impossible to prove or disprove.

Here are the negatives of how the next Doors album might have sounded had Morrison been involved:

There’s reason to believe his voice was sharply deteriorating. His alcohol intake and general substance abuse gets the most attention when his excesses are documented. But he was also a heavy smoker, and this might have been taking its physical toll, even though he was at 27 still pretty young. You can hear a gruff tone on some of the L.A. Woman cuts—like “Been Down So Long,” “The Changeling,” and “L.A. Woman” itself—that’s coarser than anything he’d previously cut, though it works well for this material. His smoking, and an associated hacking cough, were apparently getting even worse in his last few days in Paris. How long would it have been before he lost some of his vocal range and depth?

L.A. Woman was tilted more towards straight blues than previous Doors records. That’s especially true of “Been Down So Long,” “Cars Hiss By My Window,” and the John Lee Hooker cover “Crawling King Snake.” But it also comes through to some extent on “The Changeling,” “L.A. Woman,” and “The WASP (Texas Radio and the Big Beat).” Again, this works well within the context of the LP, since there was variety and contrast with classic, more characteristically Doorsian songs that weren’t straight blues (“Love Her Madly” and “Riders on the Storm”), and since even “L.A. Woman” and “The Changeling” were bluesy without having standard, predictable blues structures and melodies.

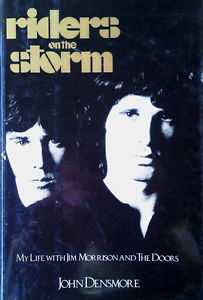

However, there’s reason to believe Morrison might have wanted to drift into straight blues that would have made the Doors less interesting or even pedestrian. Predicted drummer John Densmore in his memoir Riders on the Storm, “He would just want to play the blues, the slow, soulful, monotonous blues, which is great for a singer like him, but boring for a drummer like me.” And possibly boring for listeners, especially if it’s delivered in a croaky voice.

But there are a couple positives to this speculation too:

Although some L.A. Woman tracks seem to show some wear on Morrison’s voice, on other tracks, he crooned as well as ever. In particular, his vocals on “Riders on the Storm” are as clear and haunting as anything he sang. And that was the last song he recorded with the Doors, so it wasn’t as if his voice went into decline after the L.A. Woman sessions started. Would he have still been able to summon these kind of performances on another Doors LP?

And although some feel Jim was through with pop music and wanted to stay in Paris to write, an indication that he might have felt otherwise also comes from John Densmore’s memoir. Shortly before his death, Morrison called Densmore from Paris to see how L.A. Woman was doing; expressed some enthusiasm for doing another one; and said he’d be back in just a few months. According to the Morrison bio No One Here Gets Out Alive, Morrison told Densmore that if critics liked L.A. Woman, “wait’ll they hear what I got in mind for the next one.”

Does that mean Morrison had already written some songs we never got to hear? Or at least that he’d sketched out some lyrics or ideas? It should be noted that Densmore at least was dubious they’d be as good, writing, “I saw us spending the rest of our lives in dumpy clubs and in grumpy recording sessions.”

My own feeling, to be honest, is somewhat in line with Densmore’s. The material, I’d guess, would have gotten bluesier, but also less interesting and inspired, possibly even monotonous and burned-out sounding. And it would have been diminished by Morrison’s problematic vocals and general downward physical and mental spiral. But it certainly had a chance of being better than the pair of utterly unmemorable albums the Doors did record without him.

Did Morrison possibly have in mind material that might comment on his dire personal situation (particularly the threat of a prison sentence), and push the limits of what was considered acceptable in pop music, particularly via controversial lyrics? We don’t know that either. But it’s interesting to consider, even without taking into account his numerous brushes with the law stemming from his anti-authoritarian behavior onstage and offstage:

6. How often the Doors ran into obstacles with presenting their original lyrics. Instances in which the Doors were censored or somewhat self-censored might seem tame now that far more provocative and profane lyrics are more common in rock and rap. Still, there were a number of interesting cases in which their words were changed for their recorded versions, starting with the opening track of their first album.

The middle section of “Break on Through” was supposed to feature Morrison repeatedly singing “she gets high,” and that’s how it was recorded. Instead, on the original LP (and single), we heard “she gets, she gets, she gets, she gets” before he goes into an extended wordless wail. That always intrigued me, even as a fifteen-year-old back in the late 1970s. She gets what? I certainly wasn’t guessing “she gets high.”

The Doors continued to sing “she gets high” in live performances, such as the one on 1970’s Absolutely Live and even back at the Matrix in March 1967. And the original uncensored studio version was reinstated on CD reissues. In fact, now it’s hard to find the censored “she gets” one, although that was the only one available when it first came out, and for many years after that.

Even as someone who advocates free expression, my own feeling might disappoint the Doors and many of their fans. I think the censored “she gets” (no “high”) version is better. The rhythm of the shorter phrase fits better into that section. But also, it’s more interesting to leave the third word to your imagination. Everybody loves his baby because she gets money? She gets sex? She gets “it,” whatever it is? She gets “high” might have been considered hip and daring in 1967 for its drug reference, but it’s frankly kind of a cheap letdown now. She smokes pot, or even does harder drugs. So what? Does that even make her cool? And was it really that unusual, at a time when so many people were getting high?

The Doors’ first album ended with “The End.” Famously and infamously, the middle section was a reenactment of the Oedipus myth. It got the Doors fired from their Whisky A Go Go gig when Morrison sang explicit lyrics about having sex with his mother. There was no way that was going into the recorded version when the Doors cut the LP, not in late 1966, and maybe not even today for most acts. Jim did chant the f-word during the instrumental break, and while that was buried on the original release, again CDs reinstate this. Or kind of reinstate it, since it’s still kind of submerged, if audible. My take is that it doesn’t notably add or detract from the track’s ultimate effect. If you want to hear the untampered “fuck the mother, kill the father” line, that’s on the Matrix tapes.

Leading off side two of The Doors was their cover of Howlin’ Wolf’s “Back Door Man,” written by Willie Dixon. Live, they at least sometimes altered the lyrics to insert the following verse, which is not found in either Howlin’ Wolf’s original or the Doors’ studio version: “I’ve got the right to love you, I’ve got the right to hug you, I got the right to kiss you, I’ve got the right to misuse you.” You can hear that on their Matrix tapes.

As there’s no Doors recording of “Back Door Man” predating the Matrix tapes, it’s not known whether they were already doing those words onstage when they recorded their first album. If they were, it’s not known whether it was their decision not to use those words in the studio, or if there might have been pressure from Elektra. It can’t even be discounted that had these words already been part of the Doors’ arrangement, they might have been cut simply for space considerations, as the additional verse would have made the song considerably longer than the three and a half minutes it occupied on the first LP. Whatever the situation, here’s one case where the omission of that pretty offensive line “I’ve got the right to misuse you” was a good thing.

Another jolting lyrical change to another song they covered on their first album can be heard on the Matrix Tapes. A key line of Weill-Brecht’s “Alabama Song” is “show me the way to the next little girl.” At the Matrix, that line was sung as “show me the way to the next little boy.” That wasn’t going to fly on a 1967 record, Elektra or not.

Another infrequently noted example of censorship, or maybe self-censorship, was “Five to One,” the final track on their third album, Waiting for the Sun. That’s because there’s just the one version, which doesn’t contain profanity. In concert, however—as numerous live tapes evidence—Morrison consistently concluded the spoken section near the end about getting in a car to go out with some people with a declared intention to “get fucked up,” those words being drawled in a drawn-out manner for emphasis. It’s an odd, interesting detour in a song largely devoted to revolutionary exhortation, but the Doors were good at mixing somewhat contrasting narratives into the same song. Yet there’s no way Elektra Records, even as one of the hippest and most progressive labels of the ‘60s, was going to allow the f-word on an album in 1968, by their most commercial act or probably anyone else.

There are two different versions of “Touch Me” that owe nothing to the words Jim Morrison sings of the principal tunes (actually written by Robby Krieger, the sole composer credited). At the very end of the track, there’s a memorable four-note staccato brass riff. That’s all you hear on the original single.

But on the mix the band intended—and again, it’s the one that has become standard on CD—you hear low vocals grunt-sing “stronger than dirt.” That was a playful quote of a jingle, if that’s the right word, in a widely broadcast commercial of the time for Ajax, where voices chant-sang the same phrase in much the same way. Maybe it was removed from the single to avoid any objections, legal or otherwise, from Ajax.

I might sound like a fuddy-dud here, but I think the “stronger than dirt” interjection is rather silly and juvenile. And dated. Lots of people would have gotten the joke, i.e. reference to the Ajax commercial, back in the late 1960s. Not a whole lot of people born after 1960 get it now, and even those who saw the commercial back then might have forgotten about it. People haven’t forgotten about the Doors, and that “stronger than dirt” reference is there forever, though it’s so brief it doesn’t seriously blight the listening experience for me.

“Build Me a Woman” is one of the more obscure Doors songs, as it wasn’t on any of their studio albums, though a concert version’s on Absolutely Live. That version’s “clean,” but the one they did on the New York PBS TV program Critique in April 1969 opens with the line “Sunday trucker, motherfucker,” although Morrison slurs the MF word to iron out the profanity when he repeats the line. It’s another odd interjection that doesn’t fit in with the song’s main (if slight) narrative, perhaps meant as a jibe against rednecks harassing hippies. Considering their career was being destroyed by canceled concerts in the wake of their Miami show, it also took some integrity and courage to sing the uncensored lyric on television, though only PBS would have allowed that then. (Would they allow it now, one wonders?)

The most celebrated incident in which a Doors lyric was censored, or almost censored, occurred on the most popular network television variety show. When the group appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show on September 17, 1967, they were famously told by a producer not to sing the word “higher” in “Light My Fire.” They sang it anyway, Morrison nonchalantly claiming to forget to change the words in all the excitement. As Ray Manzarek often told the story, the producer screamed they’d never be on the Ed Sullivan Show again. To which they responded, “We’ve done the Ed Sullivan Show.”

What’s never discussed, however, is exactly what the Doors could have sung instead of “girl we couldn’t get much higher.” It’s not easy to alter that phrase. “Girl we couldn’t light the fire,” or something as asinine and ill-fitting as that?

What’s even more ridiculous, of course, is the order to change the lyric in the first place. “Light My Fire” was a #1 single for three weeks in the summer of 1967. By the time of this broadcast, literally tens of millions of people had heard the song in its original unexpurgated guise. Was singing it a different way going to erase the memory of the original lyric? Much more importantly, if “we couldn’t get much higher” did indeed refer to getting high on drugs, so what?

When the Rolling Stones were asked to alter the words of “Let’s Spend the Night Together” to “Let’s Spend Some Time Together” on the Ed Sullivan Show in early 1967, Mick Jagger complied. (Despite some claims in interviews that he’d just mumbled some words in place of the title, you can certainly see him sing “let’s spend some time together” at times in the clip that was broadcast.) The Doors did not. And they did suffer the consequences of never appearing on the Ed Sullivan Show again, though that really didn’t hurt their career in the long run.

Some of this post has focused on some of the weaker parts of the Doors’ musical legacy. Lest anyone get the wrong impression, I want to emphasize I’m a huge Doors fan, and they’re among my top ten favorite rock acts. Along those lines, the closing section is on a musical positive that I don’t see commented upon too much:

7. The Doors were quite adept at mixing sex and romance into songs that were largely, or at least as much, about other topics. There are numerous examples, and I’ll cite a few here:

“Break On Through” is mostly about transcendence, but goes into a quite lusty and effective middle section, as cited earlier: “Everybody loves my baby, she gets”…high. Or not.

“When the Music’s Over” is about generally revolutionary behavior and sentiments. But in the middle, Morrison purrs to his baby to come back into his arms.

Morrison chants “love my girl” near the beginning of one of the most revolutionary-minded Doors songs, “Five to One.”

“Peace Frog,” which reflects the general violence/confusion of late-’60s society, is overlaid with singing chants of the line “she came,” as well as ending some verses with “She came in town and then she drove away, sunlight in her hair.” And of course “Peace Frog” is a medley with one of the band’s most overtly romantic numbers, “Blue Sunday,” as if the chaos of the streets has receded, to be replaced by blissful love.

Most of “Land Ho!” is about a wayfaring sailor. But it ends with a jubilant intention to “come back home and marry you.”

And “Riders on the Storm,” though mostly about an ominous hitchhiker, has an entire verse urging a woman to love her man, take him by the hand, and understand.

What does all this mean? That sex and death are intertwined, as might be one popular interpretation by overenthusiastic academics and psychologists? Or that you can’t have revolution without sex, or that sex and love are as important or more important than revolution?

My hunch is a different one: that for all his anti-authoritarian daring and testing of conventions and limits, Jim Morrison in particular was also something of a romantic. That’s overlooked in all the controversy he stirred with his more extroverted and outrageous behavior. But it’s certainly consistently there, and perhaps part of his search for transcendence, even if he never quite found that blissful plateau in his lifetime.