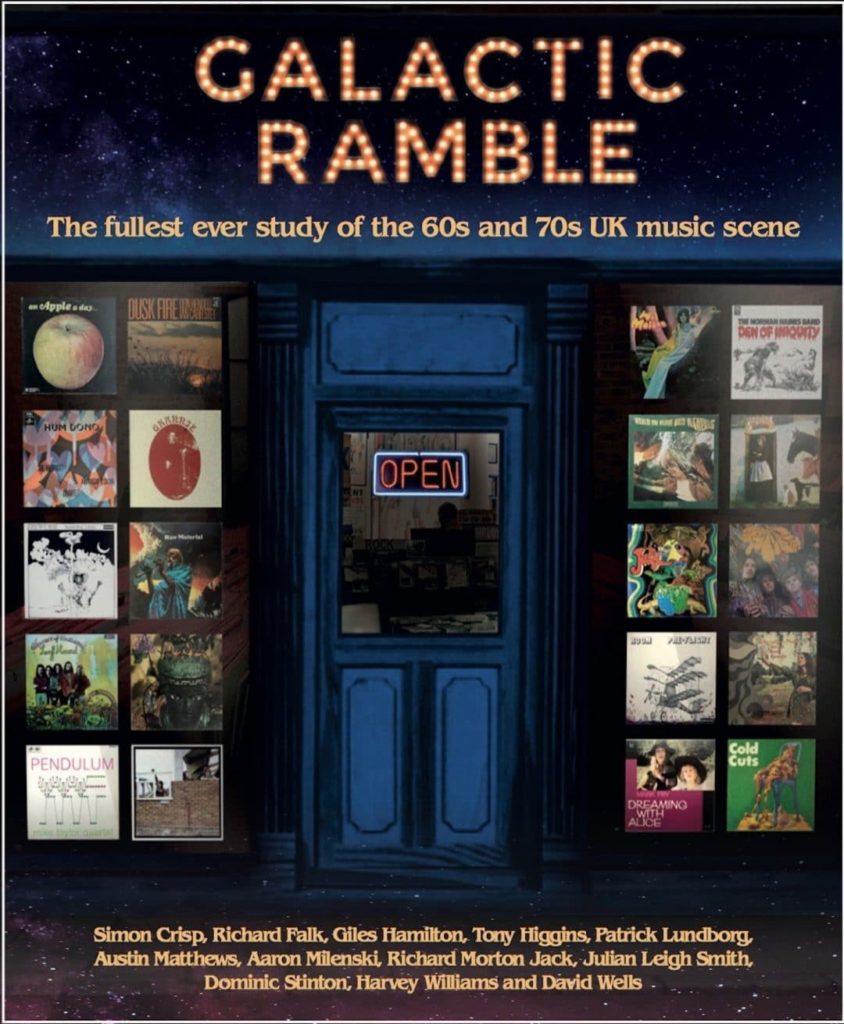

I have a lot of rock music reference books – more so than most people would consider healthy, although I do indeed consult them for work as well as pleasure. I have books of US and UK chart positions; a big discography of US ‘60s garage rock singles; every 20th century issue of Rolling Stone on CD-ROM; a history of every known Doors concert; a guide to ‘60s UK pop on TV; and five volumes of Pete Frame’s Rock Family Trees, as just a few examples. But I don’t have any rock reference books like the new edition of Galactic Ramble, a huge compendium of reviews of British LPs roughly spanning the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s. (For basic info on the book’s availability and pricing, go to galacticramble.co.uk.)

There’s the sheer size of the volume, for one thing. It’s 920 pages, coffee table-sized, with three columns of print. The focus is on rock, but there are also plenty of jazz and folk LPs, as well as a good share of “library music” discs (recorded for use on TV/film soundtracks) and sprinklings of pop, avant-garde, blues, world, and other styles. There aren’t just oodles of major label releases, but also lots of indies, private pressings, and even records cut as school projects. There are even albums by British artists only released in the US, or only available in much smaller countries. It doesn’t quite catch everything, but it doesn’t miss much.

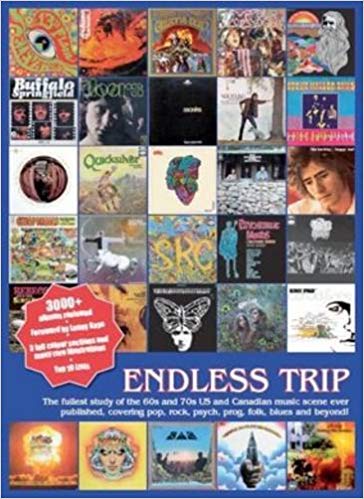

Like editor/publisher (and frequent reviewer) Richard Morton Jack’s 775-page book using a similar format for North American music from the same era (Endless Trip), it also combines reviews recently and specifically written for this volume with excerpts from tons of reviews from the era. On top of that, Galactic Ramble also has thousands of reproductions of vintage ads for LPs in the book, as well as Top Ten lists by the dozen or so contributors covering everything from the best Welsh albums to “ten titles with awful puns.”

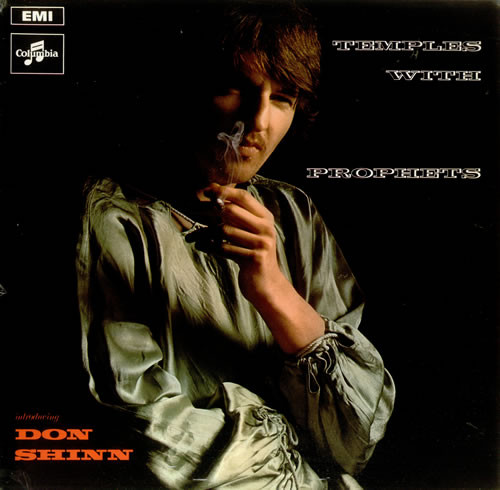

Even if you’ve got a pretty huge collection of UK music from the time, you’re bound to run across things you’re barely familiar with or totally unaware of, whether the 1970 Charlie Watts-produced album by the People Band or the jazz-soul-pop instrumental LPs by Don Shinn (who, in Morton Jack’s estimation, “proves himself Brian Auger’s equal on his organ”). Yet the bigger, and in fact biggest, records of the time are covered too, all the way up to the Beatles, without snobbery that either lowers the standing of superstars or inappropriately champions the merits of cult acts. And acts usually only surveyed through their best-ofs, like Herman’s Hermits, Peter & Gordon, and the Dave Clark Five, are rewarded with real reviews of their actual LPs, even if they rarely deserve canonization as lost gems.

Yes, these are the kind of books whose bulk and detail make some of your friends, even some of your good ones, question your sanity for owning a copy, let alone reading it from A to Z, as I’ve done. But it’s not just a mass of facts and figures. The writing’s entertaining, and the perspectives are thoughtful and informed. By treating all (or virtually all) records as worthy of consideration, and not just those that were popular or have gained or maintained a certain critical reputation, Galactic Ramble does a great service to rock scholarship in general. Would that all corners of the world get such coverage – which, in fact, Morton Jack is working on, as you’ll read.

Besides producing Galactic Ramble and similar reference books, Morton Jack is also editor/publisher (and again, frequent writer for) the glossy magazine Flashback (info at flashbackmag.com). Also focusing on the mid-1960s through the mid-1970s, it has in-depth articles and reviews on cult acts, albums, and books usually overlooked by other rock history publications. (As a disclaimer, I’ve been a frequent contributor to Flashback, though I did not write anything for Galactic Ramble.) I interviewed Morton Jack about Galactic Ramble shortly after its early 2019 publication.

This is the third book of this sort you’ve done, after the first edition of Galactic Ramble and Endless Trip. These are some of the most detailed rock reference books ever published, and not just in their length and detail. No others have the format of combining reviews written specifically for the book and discographical information with excerpts of vintage reviews from when the records were first released. What was your motivation and intentions in deciding on the formats of these books?

Before YouTube and other sites made it easy to check out obscure 60s and 70s albums, hype (usually from dealers…) was often all that hungry music fans had to go on. I found that frustrating, so decided to put together a book of candid reviews from knowledgeable music lovers (egotistically assuming that if I thought such a thing would be useful, others would too). Because I’d already started to collect 60s and 70s music papers and magazines, it seemed logical to mine them for information to add to the book, hence the release dates, adverts and excerpts from original reviews. It all grew from there. It seemed sensible to include famous albums alongside obscurities because they give interesting context, and I wanted the book to be of broad interest, not just for specialists. In fact, albums by big stars of that era (Herman’s Hermits, Cilla Black, the Sweet and many others) are barely listened to nowadays, whereas artists like COB, Vashti Bunyan and the Open Mind, who barely sold a single record at the time, are now very familiar to most lovers of music from that time.

The first edition of Galactic Ramble was pretty big, with 530 pages, but the second edition is a lot bigger, and not merely an update/revision. It’s 920 pages, almost twice as long. What specifically did you want to do and include this time around that wasn’t in the first edition?

The first edition was put together fairly quickly circa 2008, without attempting to be comprehensive. In the ensuing years I made a concerted effort to make a list of eligible albums that weren’t in it, and to add new reviews to entries that were only represented by old reviews. This edition therefore includes a large number of obscurities that I had either never heard of or was unable to cover last time, and much more ‘modern’ perspective. It’s also broader in scope, with genres covered that were largely omitted last time, such as library music and early beat. [Note to US readers: in the UK, “beat” refers to the mid-’60s rock that Americans call the British Invasion.]

Of course you didn’t write all the material, but you wrote more than anyone else. What were the most exciting discoveries for you among the albums in the edition that you hadn’t previously heard?

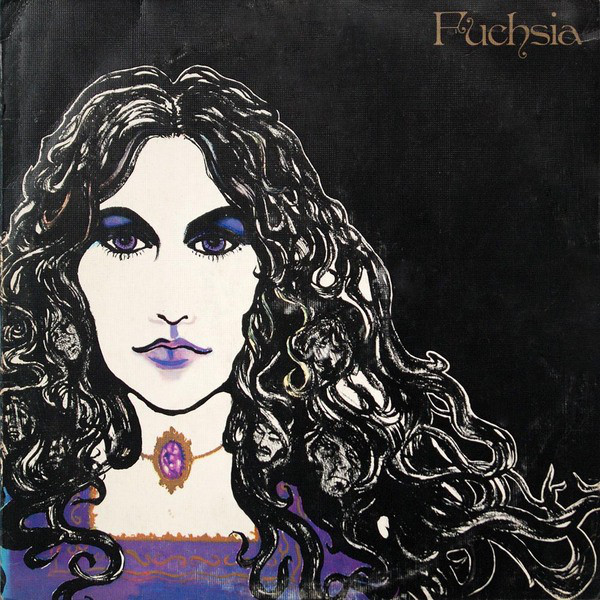

I wrote the most because I had to wade through many albums I wouldn’t inflict on an enemy!Off the top of my head, two albums I listen to frequently but hadn’t heard when putting together the last edition are Change-Is by the Rendell-Carr Quintet and the self-titled LP by Fuchsia, but there are many others. In fact, there’s one intriguing major label album I heard of in the course of putting the book together that I have yet to find a single copy of, and that still isn’t listed on any music websites. I know that it actually exists, because I know someone who has a copy… and when I find one, I’ll tell you what it is.

The great fascination of this period for me is the sheer variety and volume of music that was released: record companies had little idea what would or wouldn’t sell, so seemingly threw out as much product as possible. At times it seems like a bottomless pit, and I was and am constantly amazed at the sight of major-label albums that I had never even heard of. Discovering it all is an ongoing process. More music came out in that period than anyone can assimilate in a lifetime.

There are excerpts of vintage reviews from dozens of UK publications. These include not just the expected weeklies like NME, Melody Maker, and Sounds, but also underground papers like IT and Oz, fairly forgotten music business publications like Record Retailer, and even general interest magazines like Penthouse and Time Out. Quite a few of the reviews come from publications that are obscure even to scholars and collectors of the era, like Strange Days, Top Pops and the UK edition of Rolling Stone (which was only in operation in 1969, and had different material from the US edition). How much effort was involved in accumulating all of those issues, and what do you see as their greatest value (for historical knowledge, not the price the actual issues would fetch now) 40-55 years later?

In contrast to record collecting, very few people collect old music magazines / papers, and certain issues of certain publications are as rare as any LP. Trade papers like Record Retailer and Music Business Weekly are more or less impossible to find – maybe one or two copies of each surfaces on eBay every year. Obscure consumer magazines like Top Pops are barely any easier to find; that one ran from 1967 to 1971 (by which time it was called Music Now), but even the British Library doesn’t have them. It’s rather mystifying where they all are; I can only assume that they were thrown away in a way that the more serious and large-selling papers (Melody Maker, NME etc) weren’t. Putting together runs of them is a grueling task. In certain cases, it took me years just to establish that certain issues simply don’t exist (for whatever reason). The information just isn’t out there yet. The joy of these scarcer papers is that they cover artists who weren’t touched elsewhere, as well as containing material relating to household names that has barely been seen since. That is definitely their greatest value for me. As for the better-known papers, the sheer volume of interesting information in a random issue of (say) Melody Maker from this era is mind-boggling. To read an issue of any such paper is an extremely vivid, immediate experience for a music lover.

As a related question, it’s amazing how often some quite obscure albums were reviewed. Eleven Trader Horne reviews and nine for the first Peter Bardens record, for instance. Would you agree it’s not generally realized how thorough UK coverage was, at least in terms of sheer numbers of releases reviewed? And why do you think there were so many — to fill up space, to maintain relations with record labels, a general fanaticism among some contributors and editors, or a combination of all of the above?

In those days the music business was pretty efficient in terms of recording, releasing, promo and publicity (although by no means all artists got a fair crack of the whip). When one remembers that Melody Maker, NME, Sounds, Record Mirror, Disc and Top Pops (and many other magazines aimed at young people and the underground) were appearing every single week, it’s less of a surprise to find how much coverage there was of obscure artists. After all, no one knew what the next big thing would be.

Often a connection opened doors, then as now: Trader Horne’s members had been in Fairport Convention and Them, both of which were universally well-regarded by the music press at the time. As well as the reviews, Trader Horne received several feature articles, and Pye made a big effort with press releases and posters etc. As another example, Spencer Davis was involved in managing July, so they were widely covered (with his name mentioned in almost every case, of course).

Almost everything got at least one prominent review, though beyond that coverage often seems arbitrary. Some albums, inevitably, seem to have received absolutely no coverage whatsoever. For example, I have yet to see a single review of the LPs by Ambrose Slade and Czar, and the debut by Catapilla, all of which are well-regarded and highly prized today.

As many publications as were sourced, quite a few other reviews are out there. First there are reviews in general interest UK papers and regional UK papers in different areas and cities. Also there are the many reviews that appeared in the US (and other English-speaking countries). Of course, in many instances the albums didn’t come out outside of the UK or didn’t come out in the same form, but in many other cases they did. What were the parameters of deciding which magazines to use for review sources, and do you regret not being to include some of the others, even if you had to be selective to keep the book to a publishable size?

I restricted coverage in the book to British publications on the basis that I had to draw the line somewhere, and their critical perspectives would approximate cultural homogeneity (for better or worse). Mainstream newspapers contained hardly any proper pop coverage in that era (in stark contrast to today’s papers), and took barely any interest in underground music; in researching the book I trawled through a large number of daily papers but found very little of use beyond jazz reviews. I did excerpt material from several regional papers (typically concerning local bands being given a national shot), but of course I was never going to be able to do a comprehensive job of that. Either way, most pop / rock coverage I’ve seen in the mainstream media was superior or dismissive. As but one example, the reliably absurd Tony Palmer had this to say of the first Jimi Hendrix album in the Observer: ‘Owes everything to the Cream. Overladen with electronic effects and confuses gimmick with invention. One song hardly distinguishable from the next and all characterised by moaning, groaning and sobbing. Mostly out of tune and probably out of time.’

While it’s interesting to see how records were perceived at the time, many of the reviews were unexpectedly positive, often rather blandly so, even for many records that barely got any attention or sales. It often almost seemed like the purpose was to help sell the records as much as judge their merits — not just in the business publications where you might expect that, but also in the ones that were straight music journalism (or at least perceived as such). Do you agree with that, and do you feel like the reviews by GR writers penned recently and specifically for this book can be something of a more critically astute counterbalance?

Time-constraints meant that most album reviews were actually superficial descriptions (often heavily dependent on accompanying press releases or sleevenotes). More than one music journalist from the 60s and 70s has told me that ‘reviewing’ in in those days consisted of listening to one of the many records that arrived at their offices every day with headphones on, whilst desperately getting copy together for other parts of the paper. Considered, in-depth coverage of albums didn’t start until the late 60s, but most reviews remained short and superficial thereafter. (As an aside, for me the most perceptive reviewer of the time was Mark Williams, who wrote for International Times and later founded the sadly short-lived Strange Days.) I don’t think advertising was contingent on favourable coverage, as in many publications today. In fact, one former 1970s Melody Maker editor told me that he used to be taken out for lunch by record company promo people begging him to find them advertising space; there simply wasn’t enough room for it all every week.

In the vintage reviews, there are some amusing misfires for albums that are now established classics, some of which might have seemed ridiculous even at the time. For instance, NME thought Van Morrison sounded ‘for all the world like Jose Feliciano’s stand-in’ on Astral Weeks, adding, ‘Morrison can’t better or equal Feliciano’s distinctive style’. The same publication felt Nick Drake’s ‘voice reminds me very much of Peter Sarstedt, but his songs lack Sarstedt’s penetration and arresting quality’. How do you view such outside-the-established-party line reviews today, and were there some particularly amusing/surprising ones you found?

Inevitably, given the constraints ‘reviewers’ were usually working under, superficial comparisons to famous artists were abundant, and most reviews from that time shouldn’t be taken too seriously. I found it surprising that oft-repeated assertions about now-celebrated artists are usually false: for example, Nick Drake was warmly received by the critics throughout his lifetime, and Vashti Bunyan’s album was widely and positively reviewed. It’s also salutary to note that – then as now – many bands got a critical kicking but still sold huge numbers of records. Black Sabbath spring to mind; they’re now regarded as pioneers, but Top Pops said of their debut album ‘this stuff has all been done a million times before’. Actually, that sense of ennui is frequent in coverage of the time, as if they were living through a dull patch in the development of popular music.

Pure discographical information isn’t the focus of this book, but it’s there in the labels, catalog #s, notes about inserts (lyric sheets and posters), notes about whether they were acetates or private pressings, if they were released outside of the UK only (and where if so), and so on. But perhaps the most valuable component here are the release dates, which are not simply years, but month (if known, as usually is) and year. A lot of misinformation has been passed around about release dates over the years, sometimes for records that were very popular or have huge cult followings, like Blonde On Blonde, Forever Changes and What We Did On Our Holidays. How important did you feel it was to get these as accurate as possible, and how did you pin down the dates of release as accurately as you could?

I wanted the book to contain a large amount of ancillary information that was unavailable elsewhere, and pinning down release dates was a large part of that. I dated albums by using the first reference to a finished (ie post-manufacture) product that I could find. Often this came in the form of an announcement about a forthcoming release, an advert or a review, but sometimes press releases and similar ephemera. It’s not a precise science, though – some albums were reviewed months after they were released, and it’s a fallacy that catalogue numbers were chronological. And, as you say, confusion continues to dog the release dates of even the best-known albums: June 1st 1967 was the date given on original advertising for Sgt. Pepper’s, and the one that has been cited ever since, but it’s now widely accepted that it was in fact on sale in late May.

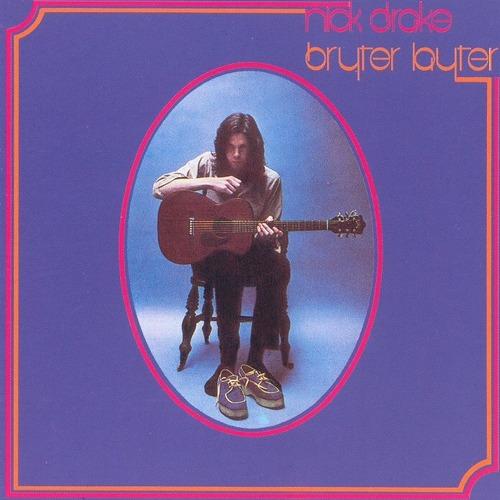

Another date that’s been inaccurately reported for many years is the release date of Nick Drake’s second album, Bryter Layter. How did you pin that down in particular?

Bryter Layter was originally trailed as a November 1970 release, but artwork delays caused it to be pushed back to March 1971 (greatly to Drake’s frustration). The earliest review I’m aware of was dated March 13th, and all the adverts for the album are from that month. In addition, paperwork and letters possessed by the Drake family bear out this date.

Even with 920 pages, some records and artists from the mid-’60s through the mid-’70s, the decade more or less that the book covers, were not included. Beyond one or two oversights, there seemed to be some specific considerations: that it was too late (like The Who By Numbers), that it wasn’t enough of a significant variant from the UK release (the US counterparts of many UK rock albums), or that it was too pop (the only P.J. Proby review is the one with guys from Led Zeppelin). And there’s little reggae, though quite a few reggae acts (including some big artists like Jimmy Cliff and Bob Marley) were based in the UK for a while. Of course, you couldn’t have included everything that might have possibly fit in without expanding the volume to an unpublishable size, but some omissions will be noticed by readers. What were the parameters for what was included, especially when a release or artist was at the margins of your scope?

As you rightly say, space wouldn’t have permitted truly comprehensive coverage, much as I’d have liked to have aimed for it. I deliberately omitted most ska, reggae, easy listening and traditional folk, though ideally they would all have been covered in depth. And a lot of other omissions are arbitrary or accidental (though I hope I didn’t forget anyone of major significance). I ummed and ahhed about whether to include big-sellers like Tom Jones and Shirley Bassey, but decided that they weren’t likely to be of much interest to most readers (or, I admit, me). I used punk as a broad cut-off, as including all that stuff would have hugely expanded the book’s size and scope, and the advent of punk represents some sort of cultural shift – the closing of the first great rock’n’roll era and the start of the next, maybe.

I think your core audience is rock listeners, and the bulk of the book covers rock releases. But there’s also a fair amount of jazz, non-rock-influenced folk, and library music. There’s also some Christian rock, which is seldom covered even in the rock collecting world, and ‘school project’ discs, which some would consider ‘outsider’ music. Why did you want to cover those styles along with the expected rock?

It seemed obvious to treat the whole music scene as a single entity, and I wanted to shine a light on areas of music that collectors spend a lot of money on but critics have more or less ignored. For example, Galactic Ramble contains more reviews of 60s and 70s British jazz than any other book I’m aware of (and I’ve been asked to print just the jazz reviews as a separate volume, which I won’t). The British jazz scene in this period mirrored the rock scene in many ways – remarkable musicians pushing the boundaries of the form with the support of major labels, stunning artwork and so forth – yet finding proper coverage of all (say) Joe Harriott’s albums, including accurate release years, let alone months, was impossible as far as I could see. As a final point, modern tastes are catholic: most people I know enjoy rock, folk, pop and other areas in equal measure, whereas I get the impression that music fans tended to be more tribal back in the day – and, of course, they didn’t have the huge advantage that we have of being able to survey the scene holistically. Much as I think I’d like to have lived through that era, I shudder at the thought of how narrow my musical horizons are likely to have been.

Something the book brings home is the sheer quantity of product released during this era. It’s amazing how many major label flops (some with big budgets, as your reviews sometimes note) came out, and it’s still being fully appreciated how many indies and private pressings that barely found distribution were issued. Pre-21st Century, when the Internet became huge, I guess you could say the same of all eras in recorded music: an enormous amount came out that barely sold and was barely heard. But do you think there was even more of it in the Galactic Ramble era, and that the nature of this quantity of product was different (in both the music that was produced and why it was recorded/released) than in other eras?

I think the immediately postwar generation was remarkably good at playing instruments. I can only assume that, in the absence of modern distractions, 50s and 60s teens spent a great deal more time hunched over guitars or keyboards than is feasible today. It surely helped that there were far more opportunities to play live in those days (partly because there was far less competition as to what people could do with their evenings, no doubt). Finally, the generational shift and newfound availability of various sorts of drugs in the 60s made young people much more capable of expressing their individuality and imagination than before.

That period happily coincided with major labels being awash with money and having a complete lack of awareness as to what would or wouldn’t sell. There was also an enlightened attitude towards what they recorded in many cases; Hugh Mendl at Decca, for instance, believed that the company had a cultural responsibility to record uncommercial music, irrespective of sales. It helped that the majors (EMI, Decca, Pye, Philips and one or two others) owned their own studios and had ready access to pressing and distribution, making it a low-risk business with obvious tax-efficiency for their many other interests.

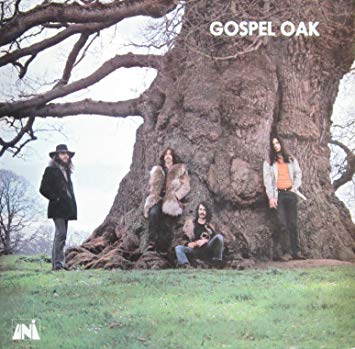

Having said all that, it’s also worth remembering that records were extremely expensive in the 60s and 70s: the vast majority of new acts were doomed to failure simply on that basis. For example, in the same week that Paranoid by Black Sabbath, Gasoline Alley by Rod Stewart and Mad Dogs & Englishmen by Joe Cocker were released in September 1970, the following also appeared: World’s End by Andwella, Love Songs by Mike Westbrook, Indian Summer by Panama Limited, Greek Variations by Neil Ardley etc, The Magic Shoemaker by Fire, The Road by Quiet World, Key Largo by Key Largo, Seven Ages Of Man by Stan Tracey, Heavy Petting by Dr. Strangely Strange, Half-Baked by Jimmy Campbell, and Gospel Oak by Gospel Oak. Needless to say, there were many others out that week too, both British and from elsewhere. No wonder the more obscure ones are so rare today!

As a final thought, it’s interesting to see how many mediocre artists got to make albums when fine ones didn’t. Why did Decca put out the mind-numbing LP by The Wishful Thinking but no album by Timebox? Why did EMI put out five LPs by Freddie & The Dreamers and none by the Action? One can only conclude that blind luck played its part, as did being championed by someone influential at a label, as David Hitchcock suggests in his wonderful introduction to the book. (And, by the way, Aaron Milenski deserves the Presidential Medal Of Freedom for wading through the Freddie & The Dreamers catalogue for the book.)

As an inevitable related question, this quantity naturally included a lot of generic or even rotten records. For you and the other writers, was it often a challenge to grit your teeth through so many of them, and to find something to say about, say, a group trying desperately to sound like Uriah Heep, without any point or talent to bring to the exercise? Or artists that simply didn’t seem to have any identity, anything distinctive to say, or any clue as to which direction they wanted to pursue?

Much beyond the beat and folk booms, unrelentingly tedious albums were surprisingly few and far between, in my experience. Most of them have decent musicianship, at least, and there’s usually at least one track that justifies the time spent listening to the whole thing. I think the vast majority of boring albums from that era were specifically intended to be background music (easy listening, in other words), and the majority of those aren’t in the book. Nonetheless, I’m sure that there are still a few cheap obscurities of that sort lurking out there with one or two killer tracks on them.

Some of the reviews written specifically for the book challenge received wisdom about quite a few of the records, both by championing ones that have been ignored or disparaged, or criticizing ones that are beloved by critics and/or audiences. Sometimes they almost seem to be spoiling for a fight, like when a Searchers review states ‘even as a singles band they didn’t leave us much to remember. Beyond ‘Needles And Pins,’ how many of their hits can you name?’ And there’s revisionism that can cross the line to extremism, like the review of Jesus Christ Superstar that ends, ‘Has there ever been a better rock opera? Certainly not Tommy.’ I realize you’re not in agreement with every review not written by yourself, but do you have some thoughts about the value of presenting some different and even unpopular viewpoints? And of sometimes presenting radically different opinions of the same album by GR writers, when there are multiple GR reviews of a record?

As long as a review isn’t straightforwardly dismissive, I’m all in favour of an informed music fan expressing their own strongly held view. One of the benefits of offering multiple perspectives is that it emphasises how meaningless individual critical viewpoints are. All the contributors to the book have spent many years listening closely to albums and are able to articulate why they do or don’t like something. I was keen to get their personal perspective, rather than some sort of bland attempt at objectivity, and of course some of their statements (and mine) in the book are intended in a spirit of mischief. The book is meant to be a guide, not a dogmatic final statement, and I hope it communicates far more enthusiasm than negativity.

There are many ads reproduced in the book, many seldom seen since they were printed, even for some really huge acts. Besides giving the book some graphic interest, what do you think are the most historically valuable aspects of those ads? And what were some of the most entertaining/unexpected ones you came across?

As with the reviews we discussed earlier, it’s intriguing to see quite how many obscure albums had paid advertising across several publications, and how various acts were perceived by the marketing department of their respective record labels. Often they had no clue, hence Decca vaguely describing The Human Beast’s sole LP as a ‘worthy progressive album’ or Fontana blandly stating ‘It’s a good album’ of Faintly Blowing by Kaleidoscope, or Philips optimistically urging ‘Hear this album. You’ll like it!’ of the sole LP by Junco Partners. My favourite is maybe the advert Trojan placed for Skinhead Moonstomp by Symarip, which shows the cover (depicting a bunch of moody skinheads) with the tagline ‘A must for a gay party’.

It’s fascinating for me to see trivia I wasn’t aware of speckled throughout the reviews (principally in the newly written ones, of course). I never would have suspected, for instance, that the 1970 CBS double LP sampler Rock Buster, with a young Arnold Schwarzenegger on the cover, includes a completely different take of Trees’ ‘Polly On The Shore’. Was finding out such things something you enjoyed about doing the book, and do you have a couple of particularly memorable such examples/discoveries?

Because pressing plants were so busy in that era, errors were inevitably made, most of them quickly corrected. I wanted to pin down as many of these as possible in the book. Some, such as the very early copies of the first Stones album (that play an amateurish and much longer take of ‘Tell Me’) are now fairly well-known, but others – such as the Trees track you mention – are still pretty much secrets among collectors. Another prominent example is the Bumpers compilation on Island, which contains a remarkable number of alternative versions of well-known album tracks, presumably in error. Other examples include early pressings of the debuts by Van Der Graaf Generator, Mott The Hoople and Atomic Rooster, all of which had rare erroneous pressings that play different music to most copies.

This hardback is a limited edition of 500. Are you planning a paperback, and if so, when will that come out, how available will it be, and will there be any changes to the content?

A paperback will certainly be available, probably towards the end of the year (I wanted to give the hardback time to sell out, which is happening faster than I envisaged). The paperback will of course have various typos corrected, and one or two minor additions, but nothing substantial. For example, since the book came out a couple of months ago I have found two vintage reviews of the rare LP by Kestrel, and realised that I accidentally omitted In Camera by Peter Hammill. Mildly frustrating, but not grounds to recall and pulp the run.

How has the reaction been so far? Not just in terms of anyone asking why something wasn’t covered, but maybe unexpected feedback that’s made you aware of releases or other info that wasn’t known before the publication?

People tend to be quicker to comment on what has been omitted than on what has been included! I’m always happy to hear about errors or omissions, but in most cases the latter have been irrelevant for the book. I have yet to have any bombshells dropped on me, but hope some shall – I love unearthing and sharing new info, that’s really what the whole exercise is about.

I’m pretty sure you don’t want to keep producing ever-expanding editions, but would you do another Galactic Ramble if considerably more information became available, both in terms of more obscure albums and other things about the records already covered?

Yes – but that’s a huge if… This edition took ten years of more-or-less consistent work, and I sincerely doubt that enough relevant and worthy new material will surface to justify another completely new edition. However, I will certainly keep tabs on albums that aren’t in the book, and will perhaps compile an addendum (which I’ll make available for free to people who have bought the book).

Would you consider doing an expanded edition of Endless Trip, as there’s certainly been a lot of additional records and info you’ve become aware of for North American releases since that book came out?

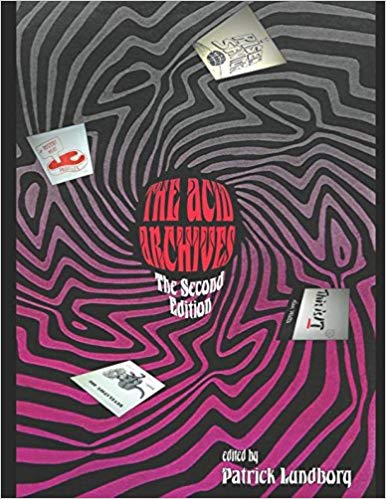

Yes, I certainly intend to put together an expanded edition of Endless Trip, though the scale of the task is daunting. Like Galactic Ramble, the first edition was put together fairly quickly and covered much but by no means all of the eligible music. However, given the vastness of the American scene, any second edition of that will still have to exclude private pressings. For coverage of private pressings, people will need to stick to The Acid Archives, which is of course a wonderful book.

You’re already underway on another volume of sorts in this reference series, Hazy Days, covering Australian and New Zealand albums from the same period. That’s an area that’s received far less coverage than rock from the UK and North America in the same era. What’s your motivation in doing this book, and what are you hoping to document/unearth?

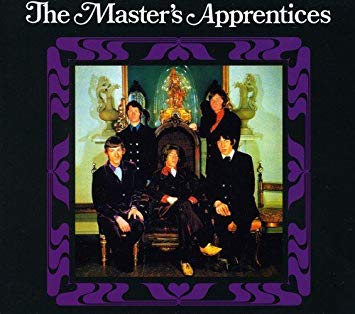

It’s astounding how much worthwhile music was made Down Under in this period, the vast majority of which was barely released over there, let alone internationally. I have long planned to collate as many of these albums as possible, in order to spread the word about them. Alongside many fine but uncommercial acts like Tully and Tamam Shud, artists like The Masters Apprentices and Renee Geyer would surely have been international stars given better exposure. It’s harder to dig out the facts behind Australian and NZ albums, as there was far less of a pop music press over there, but I am making steady progress and am lucky to have the support and assistance of one or two local connoisseurs, as well as superb and knowledgeable co-writers like Aaron Milenski and Richard Falk. It will be a wonderful book and I am thoroughly enjoying putting it together.