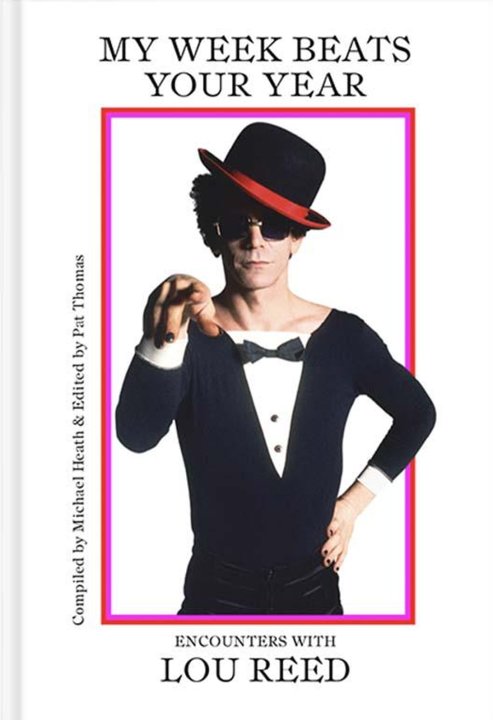

Lou Reed was notorious for giving acerbic interviews and hostility toward journalists. There’s certainly some of that in a new 300-page collection of three dozen interviews spanning 1971-2007, My Week Beats Your Year: Encounters with Lou Reed (on Hat & Beard Press, compiled by Michael Heath and edited by Pat Thomas). Asked “are you happier as a brunette?” at a 1975 press conference at Sydney airport, Reed retorted, “Are you happier as a schmuck?” Added Lou a few questions later, “You don’t stand a chance with me, you know. Get your own parade.”

Yet he’s also, and not infrequently, pretty informative and straightforward, depending on whether he seems to repsect and trust the interviewer. Anyone with an interest in Reed (and the Velvet Underground, who do come up in conversation fairly often although he’d left the band in 1970) will find a lot of comments with worthwhile perspectives and uncommon nuggets of trivia and recollections. Even the pieces in which he’s polite and friendly are usually spiced with some sarcastic and cutting remarks, some of them simply rude, but some also pretty funny and witty.

Even if you’re widely read on Reed, you’ll certainly come across interviews you haven’t seen. Many of them were never reprinted before (or, in the case of a few radio interviews and press conferences, never printed anywhere before, to my knowledge).

The sources range from high-circulation mags (Rolling Stone, Creem, Circus, MOJO, Melody Maker) to unlikely mainstream publications (Hit Parader, Hits), big daily papers, Trouser Press, and the BBC to outlets where many wouldn’t think to look. Bob Reitman’s 1976 interview for the Milwaukee Bugle-American, for instance, is one of the better lengthy chats Reed gave (and virtually devoid of any rancorous attitude or game-playing). There’s even a 2003 interview with Kung-Fu magazine.

Some of the writers were celebrities in their own right, including Lenny Kaye, Lance Loud, singer-songwriter Elliott Murphy, and, of course, Lester Bangs (though just one, from the non-obvious source of Let It Rock, is here). Besides presenting the text of the original interviews, the original pages and covers are often also reproduced, though the type in those is so small you’ll be glad all of the text is also presented in readable size in the format used for most of the pages. As the first volume to collect a lot of his interviews in book form, it’s a welcome addition to the Lou Reed library.

Editor and longtime Lou Reed fan Pat Thomas has written about music extensively for decades. He’s also branched out into documenting the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s with his recent books Listen, Whitey!: The Sounds of Black Power 1965-1975 and Did It! From Yippie to Yuppie: Jerry Rubin, An American Revolutionary. I recently spoke with him about My Week Beats Your Year: Encounters with Lou Reed, and what Reed’s interviews tell us about this talented but mercurial genius.

What gave you the idea for the book?

Me and my co-author, Michael Heath, are both kind of lifelong Lou Reed nuts. We kept kind of discussing over the last several years, was there a book of Lou Reed interviews? There was something called The Last Interview and Other Conversations. I thought oh geez, we’ve been scooped. I bought the book, and it was this extremely thin book with only five interviews with Lou, most of them later in his life. So Mike and I realized that the playing field was wide open. That’s how the whole thing started.

There are a lot of Lou Reed interviews, in spite of his reputation for being one of the most hostile rock stars toward interviewers. (If you could call a guy with one big hit single and one Top Ten album that he virtually disowns a rock star, that is.) There must have been some selectivity involved in what to include, even in a 300-page book. What were your main criteria for what should be featured?

Basically, we wanted to span his whole career post-Velvet Underground. We certainly were looking for provocative stuff. For example, the August 1974 and July 1975 Australian stuff [taken from press conferences at the Sydney airport]. But to kind of have a balance, with obviously the focus on the ‘70s and ‘80s. The criteria was just kind of what was interesting, and I want to throw some credit to Mike Heath on this. ‘Cause he kind of led the charge with the first round of research.

A good number – certainly the majority – of the interviews are his lesser known ones. Some are really obscure, even to big Reed fans. What kind of detective work was involved in digging these out?

He kind of did a lot of that research. He went through the Underground Newspaper microfilm collection, which has alternative papers of all kinds from the mid-’60s through the mid-’80s. That’s where he got a bunch of the pieces in the book, especially the more regional interviews, like the ones with Bob Reitman in the Milwaukee Bugle-American, and Charlie Frick in New Jersey’s Aquarian Weekly. Then of course youtube, at least for these television and radio interviews that we grabbed, was very useful. I’m kind of proud of the fact that there is such obscure ones.

Reed’s so infamous for giving hostile, or at least uninformative and/or game-playing, interviews that it might surprise some readers to find that he played it fairly straight sometimes, even back in the mid-‘70s when he built much of this reputation. I had the feeling that what kind of interview you got depended on a number of factors. If he thought the interviewer was cool (especially if he already knew them and perhaps respected them in a context different than journalism, like Patti Smith Group guitarist Lenny Kaye), he’d be pretty friendly and forthcoming. If he was having a good day, or in a good period of his life, he’d at least stick to fairly normal standards of politeness and decorum. If the interviewer stuck to the subject he wanted to discuss the most (usually his current album), he’d be easier to deal with. On the flipside: if he thought you were uncool, or it was a bad day/time in his life, or you pressed him on subjects he wanted to avoid or was uninterested in, you might not only get a bad interview, but get insulted, or maybe walked out on. Would you agree?

I would. We recently did a Lou Reed book event in L.A., so I invited a couple of LA-based journalists who are in the book. So there’s a guy by the name of the Dave DiMartino. In 1980, he interviewed Lou for Creem. He said he was expecting the grouchy monster. But he also kind of thought ahead. He knew that Lou was a big jazz fan, so he brought Lou some obscure jazz record and gave it to him, and kind of greased Lou with that record and that discussion. And then kind of switched over and talked about Lou himself.

Some of the interviewers were pretty fawning over what many listeners, even many fans, would say were among Reed’s lesser albums (but happened to be recent at the time of the interview), like Rock and Roll Heart. Reed seemed to lap that up and hence give them a better interview than normal. That might not have been so interesting when sticking to the subject of those albums, but it might have made him more open to discussing other topics too. Did you also get that sense, and that maybe some interviewers, whether in the book or elsewhere, did this so they’d get a more cooperative conversation?

Yeah. I think it was a really tricky balance, because Lou obviously wanted you to fawn over him. But he also didn’t suffer fools gladly. So you had to walk this fine line between kissing his ass. But you also really had to be knowledgeable about Lou’s career. I think he was not into general questions.

Lou ultimately was, like many of us, kind of a nerd. So if you could either accidentally or on purpose find that topic that he could nerd out on…it might be himself, obviously. Like if you said “oh, I really love the guitar tone that you got on the Blue Mask album,” then he would geek out on equipment or something with somebody.

With the exception of maybe people like Lenny Kaye or possibly Lester Bangs, who knew how to play him in advance, I think everybody just felt thrown to the wolves. This guy Rex Weiner [who did an interview published by Rolling Stone Italy in 2006] also came [to] this recent LA event. He said that he was kind of expecting asshole, and was kind of pleasantly surprised when he didn’t get one.

I’d like to compare Reed’s interviews with those of a couple other guys of whom I know you’re huge fans. Van Morrison is also noted for being hostile and/or abrupt with many interviewers, Yet, like Reed, he actually did (and still does) a fair amount of interviewers, in spite of his reputation of despising them. And sometimes the interviews are good. He’s even discussed his past in a lot of detail, without anger, on liner notes to Them and Bang label-era solo reissues, and on camera in the Bert Berns documentary [Bang! The Bert Berns Story]. Do you see some similarities between Reed and Morrison in how they handle the media, and how their kind of manic personalities might determine how an interview goes, sometimes due to factors out of the hands of the interviewer?

As you know, I’m like the world’s biggest Van Morrison fan, so I certainly some thoughts on this. First of all, I know for a fact that those liner notes in the recent reissues was him basically being interviewed in-house, and then somebody editing that so it felt more like an essay. I would agree, yes, if you go over Van’s entire career, he’s done a lot of interviews. But I think he’s probably done a lot less than Lou did. And also, Van famously went through a period that he’s come back out of, where he either refused or wanted total control.

For example, about fifteen years ago, I saw there was an interview in a period when Van was not doing a lot of interviews. It said, exclusive interview. As I read the interview, I realized he was being interviewed by his then-wife. And the interview was credited, or copyrighted, by his production company. So he basically either gave or sold [the magazine]a completely scripted interview. There’s a famous interview when he did the album with the Chieftains, where he’s live with one of the Chieftains, and he’s either refusing to talk or just giving very obnoxious…[There’s a detailed account of one especially hostile interview, with Liam Fay of Dublin’s Hot Press, in the introduction to John Collis’s book Van Morrison: Inarticulate Speech of the Heart.]

So like Lou, he can certainly shut down an interview, or has shut down interviews. But yeah, in his older age, he’s kind of come around full circle. I think that Van might be, of the sort of bigger names, the most cantankerous interview.

The other guy to compare him with is Bob Dylan. Dylan’s not as noted for being hostile as Reed and Morrison (though he sometimes was in the mid-‘60s, most famously in a scene in Don’t Look Back). But he’s noted, maybe even more so than those guys, for game-playing, and not giving the expected answers. Or not even giving honest answers, making up misleading ones for his amusement. Do you see some of that in Reed’s interviews?

I think Dylan…he can be cantankerous. He more just likes to maybe play with the journalist, although he’s capable of giving straightahead answers. There was this famous interview in ’85 in Spin, and the front cover said “Not Like a Rolling Stone Interview.” I still refer to that interview, it’s online. It’s one of the most candid interviews Dylan ever gave. I think his liner notes in the Biograph box set are remarkably straightforward.

But all three of these guys, probably if you had to rank ‘em: Van the most cantankerous, Lou the most also kind of rude, and Dylan the most elusive, perhaps.

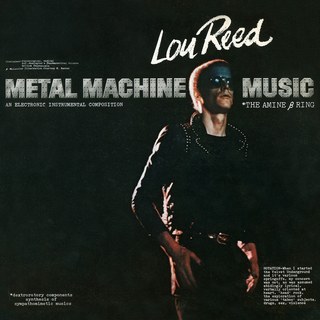

With Reed, a kind of game-playing is particularly evident when he talks about Metal Machine Music. Even in the liner notes, it’s not sure whether the record’s a joke or a serious artistic statement. He keeps on riffing on that in his interviews, though maybe he was more forceful on the side of “it was serious” toward the end of his life, when it got revived onstage and some younger musicians praised it without irony. Do you think it was a serious artistic statement, was it kind of a joke (especially on the business) he wanted to get away with, or was it (as I’d say) kind of a combination of the two?

I would agree. I think it initiated a little more as a “fuck you” to the label, possibly to his fans. Then over time, I think he embraced… though he never played with La Monte Young, he obviously as we know played with John Cale, who played with La Monte Young. Lou had an affinity for the avant-garde. He loved Ornette Coleman, or whatever. So I think as he got older, Lou saw [Metal Machine Music] as like, “this is my contribution to the type of stuff that somebody like Cale was doing with La Monte Young.” I think over time Lou saw Metal Machine Music as his great avant-garde artistic statement.

But people may be surprised how much Lou also loved, at least at one point, mainstream music. Iain Matthews from Fairport Convention told me he met Lou in New York in 1974 or ’73, and Lou said, “I know who you are.” And Lou started playfully singing to Iain Matthews the songs off of Iain’s most recent Elektra album. When you think of Iain Matthews, you think of this sort of soft folk-pop or whatever you want to call it. We think of Lou as the aggressive rock and roll guy. So sometimes it’s interesting how these guys, Lou especially, would be listening to something you didn’t think he would listen to, like some kind of folky pop music.

Reed’s attitude toward his fans and more commercially successful projects could be ambivalent. With things like Sally Can’t Dance, almost like, “I put out a deliberately lousy record, and sure enough, it was my biggest seller. Which proves how stupid people are.” Almost like he got more satisfaction from proving the latter point than actually doing what he set out to achieve (sell more records). Or with Rock’n’Roll Animal, “it was a way to get the Velvet Underground songs heard,” almost like the masses couldn’t appreciate them if they were dumbed down – again proving his point, almost to more satisfaction than getting those songs heard, at least in some form. Do you also sometimes get that impression, and what do you put it down to?

I think Lou had this giant ego, starting all the way in the Velvet Underground, where Sterling Morrison – they were recording or writing a song, and Sterling played a really cool lead guitar lick or something, and Lou complimented him. Then Lou quickly said something like, “Well, if I hadn’t written this great song, you would never have played that great little guitar riff. So therefore, you should be thanking me.”

But then, because the Velvets never really took off—and I don’t know if Lou thought they should have been as big as the Beatles or whatever—he’s bitter that the Velvets didn’t have bigger success. He puts out this stuff that he considers substandard, like Sally Can’t Dance or these sort of quasi-heavy metal versions of the Velvets’ songs on Rock’n’Roll Animal. He’s pissed at his fans for buying the substandard work, and he’s also pissed that they didn’t buy his so-called quality work.

So there’s a lot going on there inside of Lou’s head. A psychiatrist would have a field day with this. Another one of our favorite artists is Pete Townshend, who also kind of I think has these various issues, although they manifest themselves maybe in slightly different ways.

But yeah, I think Lou sort of disdains his fans. Some of the people in my personal life who kind of hate other people, I realized as I got older that usually people that are bitter against other people kind of have a little bit of self-hate thing going on. I think Lou had that, at least at some points in his life.

The book spans 1972, when he first started to get noticed as a solo artist, to the early twentieth century. But it doesn’t have any interviews from when he was in the Velvet Underground. He didn’t actually give many then, as they weren’t too commercially successful. But he did give some, including some that were on the radio, but not in print. Was there a deliberate decision not to include those, maybe in part because they’ve been reprinted in specialist Velvet Underground books?

I think we felt, first of all, that there’s been a book or two with some of those. But more that we didn’t want to muddy the waters, so to speak. We wanted it to just be, like, this is Lou’s solo career.

Back in the Velvet Underground days, his few interviews might have been kind of eccentric at times, but definitely weren’t hostile. Also talking to fans of the band from back then, Lou always seemed pretty friendly and sincerely appreciative when fans would speak with him and tell them they liked the band. This friendliness, certainly to the media, seemed to change quickly after Transformer and a fair degree of commercial success, and a lot of notoriety. My feeling is that in the VU days, commercial success and media exposure was so meager for him that he was fairly eager to cooperate (and interact on a human level with fans) when he could get it. When things finally did turn around for him with Transformer, he seemed ill-equipped to deal with the attention and fair degree of fame, maybe in part because the lack of that for his superb work in the Velvet Underground had embittered him, and he thought what he was getting attention for wasn’t as good.

I think Lou pre-fame, pre-Transformer, was probably a bit more of a regular guy. Peter Abrams, who recorded those Matrix tapes [of the Velvet Underground in San Francisco’s Matrix club in late 1969] that eventually came out officially – I remember him telling me, or maybe I read an interview, or both, that they were at the Matrix for several days and he was recording, and Lou was just a regular dude. And he got regular conversations. And then [the Velvet Underground’s] 1969 Live album, [more than] half of it is from the Matrix tapes, and [some] of it is from Texas. But the part of it that’s Matrix tapes was Abrams doing a quick mix of those four-track tapes and just giving it to Lou at the time, [in] ’69, just so he could enjoy them.

Even though Abrams wasn’t an interviewer, I think this standoffishness comes later. One, with fame. And possibly, let’s face it, there’s all kinds of drugs that Lou seems to have been taking. Amphetamines, maybe some heroin, maybe not. But we do know that he was definitely drinking and drugging a lot throughout the ‘70s. And he just became this Lou Reed character.

There might be an interview in the book where he [says] “nobody does Lou Reed better than me.” [For example, in a 1977 interview with Allan Jones for Melody Maker that’s included in My Week Beats Your Year, Reed states, “I’m told that I’m a parody of myself. Well, who better to parody? If I’m going to mimic someone, I might as well mimic somebody good. Like myself. I can do Lou Reed better than most people, and a lot of people try.”] I think what he means is not just the music, but this whole – he sort of becomes a caricature of himself. The album cover of Take No Prisoners is all kind of about Lou Reed as a caricature, like a cartoon character.

So yeah, he’s playing a little role. People used to say that Bill Graham would be on the phone screaming and yelling at some other concert promoter, and then hang up the phone and smile to whoever was in the room. I’ve heard similar stories about Elliot Roberts, Neil Young [and] Joni Mitchell’s manager. It’s a little bit of an act with these guys. I think that might have been a little bit with Lou, consciously or subconsciously. It becomes a bit of a charade.

Were there any interviews you would have liked to use, but didn’t/couldn’t, whether because of rights issues or not being able to find them, or something else?

At one point, it seemed like the bigger magazines, like Rolling Stone and Melody Maker, were kind of holding their interviews for ransom, so to speak. Our budget was everybody would get a hundred or two hundred dollars. Maybe if it was a bigger magazine, they might get a few hundred dollars or more or something. Some of these bigger magazines [were] like, we want $1000 for this. So there was a lot of negotiation. Elliott Murphy [himself a singer-songwriter who’d already released his debut LP by the time he interviewed Reed in 1975 for a piece in Circus that’s in the book] wanted a little more money than everybody else, so he tossed in a Polaroid of him and Lou together.

What was behind the reasoning of not choosing the interviews you didn’t use? Maybe they were too well known (like the ones with Bangs), or had been reprinted elsewhere? Or were just not that good, or redundant with better ones that made the cut?

The only thing that I did – I pulled out some of the later period interviews. In other words, stuff from the ‘90s, early 2000s, [that] to me seemed a little redundant. I think I might have only pulled out about three or four of Mike’s original list. We certainly went light on the Lester Bangs stuff, because I felt like that has been printed a lot, or at least reproduced on the Internet a lot. So we just kind of picked one Bangs thing from November ’73. In that case, we went for Let It Rock magazine rather than Creem, just because it was a little more obscure. I think when all is said and done, we got pretty much everything that we wanted to get.

One of the most recent interviews, with The Guardian, was a good example of how not to interview Reed, who walked out on it (and was persuaded to come back in and curtly finish). I like how Luc Sante wrote in the foreword, “He reduces a pathetic Guardian stringer to tears—deservedly so perhaps, given the wilted lettuce tenor of his questions.” While I don’t think being rude to (let alone walking out on) an interview you’ve scheduled is defensible, it almost is in this case, with the writer being so naive as to think that Reed will bond with him just because he likes “Walk on the Wild Side,” and starts off with tired and fuzzily articulated questions about subjects from his fairly distant past that Reed’s sick of discussing by this point. Do you think Reed attracted more of those kind of inappropriate interviewers than normal because of the nature of his work, or maybe it just seems that way because he had a much lower boiling point than most stars, who’ll usually field the questions even if they have to spout stock answers?

Probably it’s a mixture of all of that. I think that some of these, like, more mainstream newspapers probably just sort of assign somebody willy-nilly to the job, versus where somebody like a Mojo or Rolling Stone will be like, “let’s bring in this guy because he’s a big Lou fan, or Lou already knows him.” There’s actually an interview that’s not in the book, I don’t think we even considered it for the book, but it’s I think from the 2000s, where the interviewer is a TV interviewer. I think it’s British, maybe European. But the guy says something maybe disparaging about Lou’s more current work. And Lou quickly says something like, “well, that’s an interesting question, because everything that’s on TV is totally garbage. So you’ve got a lot of nerve asking me if today’s music is garbage when you’re part of the problem.”

Does Lou have a much lower boiling point? I think he does. Let’s go back to Van Morrison for a minute. Van often has said, “Would you interview a plumber for three pages? No. You should just consider me like a plumber, except that I’m not a plumber, I’m a singer-songwriter.” Van also has this slogan of like, “the showbiz slogan is, the show must go on. And I say, it doesn’t have to go on if you’re not in the mood for it to go on.” So Van is someone who doesn’t want to play the game. I think Lou played the game a little bit more than Van, but almost, like, punished the journalists for participating in their role.

I think Lou maybe was a little more eager to sell records than Van. Let’s face it, there were times when Lou wasn’t really selling records. I think he felt like, “Well, I better do this, or I might lose my record deal (laughs).” But again, he’s resenting the process, I guess is the best way to say it. When I think somebody like Gordon Lightfoot may not like to do interviews, but he realizes, “Well, this is part of the process.

It’s shocking how some of the worst and most poorly prepared interviewers are from some of the best publications, or at least some of the most respected ones. The Guardian is one of the best daily papers in the world. Another of the more recent interviews is done by a Rolling Stone reporter (albeit Rolling Stone Italy), who doesn’t seem too knowledgeable about his career or passionate about being there, and seems lucky to get away with a reasonable piece considering much of the territory covered is well worn. Is it almost like even major publications sometimes don’t take rock seriously enough to send someone well versed in the subject or up to the task, or are unaware of what you need to get something interesting out of a guy who by this time was known to be mercurial and temperamental with the media? Like the Guardian writer who thinks gushing over “Walk on the Wild Side” will work.

I know, I know. That’s not gonna work. You need to tell Lou you like his latest album, whatever the hell it might be. My thought was Rex, the Rolling Stone guy, should have known better. Because I think Rex is capable of doing the research needed.

Unfortunately too, it’s also a little bit of – over the last twenty years, it’s gotten harder and harder to get those writing gigs. So I think that cynically, some of these writers may be like —I’m just speculating — “if I can get this interview with Lou Reed and then sell it to a European magazine, I’ll do it.” So there’s a little bit of mercenary probably going on both sides of the fence there.

It’s interesting that while Reed was known to sometimes be infuriating to work with going back to the Velvets days, he often praises some of his colleagues fervently in interviews. Like he says Nico’s The Marble Index, Desertshore, and The End “are so incredible, the most incredible albums ever made,” though attempts to work together in the mid-‘70s apparently worked out badly. Or he’s grateful to Warhol for not demanding a percentage of future earnings when he was fired, though according to several accounts, the break was far more fractious and complicated than that. Did Reed maybe find it easier to be charitable when talking about them to the media than in person?

Two comments: selective memory and very mercurial. [Some] of that stuff that you just mentioned is all in the Lenny Kaye interview from [the] mid-‘70s. And obviously, maybe partially because it was Lenny, he’s almost over-gracious in that one. He’s also saying a lot of nice things about John Cale in that interview. Then of course, if you went to enough Lou Reed interviews, he can be extremely disparaging about Cale. Like, “Have you listened to Cale’s music?” “No, I haven’t.”

There’s a little bit sort of behind the scenes…because you realize that there’s a photo of Reed and Cale. They both are grimacing, or they’re drinking, in front of a Christmas tree in 1977. There’s a bootleg that has photos of Cale, Reed, David Byrne, and Patti Smith playing at the Ocean Club in ’76. So I think there’s periods where these guys are in contact, but we don’t know, or they don’t want us to know, necessarily, if that makes sense. It’s a little bit like the John Lennon-Paul McCartney thing, where obviously there was a lot of fallout post-Beatles. Then you might find out that those five years before he died, [Lennon] and McCartney might have been talking more on the phone than we were led to believe.

But I still remember, by the time those guys were on the cover of Optionfor Songs for Drella, they weren’t talking to each other. There’s also a famous story that Cale has told many times where after that Velvet Underground reunion in 1993, there was talk of doing a MTV Unplugged, which would be turned into an album, possibly a short tour. And Reed wanted total control. Cale just kept saying, “Lou, just relax, let’s talk about this.” And Reed said “no no no no, I’m producing the MTV project.” And finally, Cale just said, “Well, fuck you.” All’s I’m saying is that for as much as there was friendly stuff on and off over those decades, there was also a lot of anger with these guys.

One of my favorite lines in the interviews was when Bob Reitman tells Reed that Patti Smith told Reitman Reed considered producing her first album. Reed’s response: “I’ve considered whether it’s snowing outside.” Probably it would have been a lot more vicious if he seems to have already trusted him as an interviewer. Any thoughts on how Reed dealt with some unconventional turns of the conversation like this with this kind of dismissive sarcasm?

I would imagine that at some point he would have considered [producing Smith], and there’s photos of Reed and Patti together in public in the ‘70s. Could he have also been bitter because Cale wound up doing it? And that album was sort of a critics’ darling album, at the time. It still is. So again, he might have had this, “oh shit, maybe I should have done it.” Again, it’s that mercurial and selective memory thing.

He had a similar issue with Dylan, where he always claimed he didn’t really like Dylan’s music. But then of course, you hear those early demos [from July 1965 with Cale and Morrison, on the Velvet Underground’s Peel Slowly and See box set], you can tell he’s very Dylan-inspired. And there’s this story where Lou’s playing some kind of small concert or private concert in L.A. around the time of New Sensations, and he does that song “Doin’ the Things That We Want To.” And Dylan turns, I think, to [Lou’s second wife] Sylvia Reed, and says, “I love this song. I wish I’d written it.” So of course Sylvia Reed tells Lou, and Lou gets so excited that he goes out and buys all the Dylan albums that he’d missed, like twenty albums. And now he’s going around telling everyone, “Dylan is wonderful.” To the point where Lou of course appears on that Madison Square Garden [30thanniversary Bob Dylan tribute] concert doing “Foot of Pride.”

There’s several interviews where he’s like, “yeah, Dylan sucks, I never listen to Dylan.” All done before these events. He also kind of made peace with Zappa. Didn’t he induct Frank Zappa into the [Rock and Roll] Hall of Fame? Now, how many interviews did Reed do in the ‘60s where he said, Zappa sucks? I think there’s at least a few. [As one example, in an interview Lou gave Third Ear in 1970 while the Velvet Underground were recording Loaded, Reed called Zappa “probably the single most untalented person I’ve heard in my life,” throwing in “Dylan gets on my nerves” for good measure.] Again, was he jealous that they get more attention from Verve than the VU? Maybe. I don’t know. But he had this Zappa-hating thing going on for a long time, but he eventually gave up on.

[There’s] probably a little mental illness going on here too. Certainly narcissism.

It seems like one reason Reed quickly became a pretty prickly interview subject is that he got tired of being asked about his most sensationalistic songs so often, especially “Heroin.” Was he maybe too sensitive to this? Some of those interviewers would probably have gone on to less shopworn questions, or at least had sincere interest in his motivation instead of trying to use songs like that against him.

He probably just got tired of it. I’m kind of friends with Michael Shrieve from Santana, and even if you’re just a casual Santana fan, you remember that Woodstock movie drum solo, right? He can’t stand talking about it. It’s just been asked to death. I think that happened with Lou. think he just kind of burned out on it, as these guys probably do after a while.

Your own brief 1984 interview with Reed for The Notebook is in the book. He was pretty cordial and relatively friendly, if not terribly talkative and informative. Do you think that was one of those zones where he was fairly eager to be a reasonable interviewee, maybe because he especially wanted to promote a new release or things were going relatively well for him overall?

I kind of take the blame for that kind of non-interview. I was super-nervous. I think it’s the first major artist interview I ever did, and one of the things I learned over decades, especially when I did a hundred interviews for [my] Jerry Rubin [biography] much more recently, is to turn interviews more into a conversation. And certainly don’t ask questions that can easily be answered with “no,” “yes,” “no.” So when I re-read my own interview, I don’t go, “oh, Lou’s being a dick,” although he certainly could have helped me out a little bit there.

As you wrote in the book, you weren’t able to interview Reed again, in part because he didn’t show up when you interviewed the rest of the reunited Velvets during their European tour. What would you have liked to ask him if you had the chance?

So the Velvets get back together again, and I remember reading an interview with all of them. They kept talking about—at least Cale did, and I think even Lou—about how “we’re gonna have a ton of new material,” right? I don’t know if they were planning that like, “we’re gonna play it on a concert, we’re gonna make an album.” But they kept talking about these new songs. And of course, there was only one new song, which was probably the weakest thing that Lou has ever written, “Coyote.” Which not only is not a very good song, it really doesn’t feel like a Velvet Underground-type song.

So when Reed didn’t show up, I kept trying to pin Cale down – “can you tell me about these new songs?” It was as if that interview never happened. ‘Cause he’s going, “What do you mean? What new songs?” Finally he just said, sort of frustrated, “the only thing we did in rehearsal was begging Lou to turn his guitar down, because he was always the loudest guy in the room,” for these 1993 tour rehearsal[s]. And kind of just blew me off. So had Reed been there, in retrospect, I would love to have kind of tried to pin him down. Like, “Are you writing new songs for this band, this reunion? Would you like to be writing new songs?” That’s the angle I might have tried to go down if I had been able to interview Lou, specifically in 1993.

What are your favorite Lou Reed interviews?

I’ve always loved those two Australian interviews. Right before we decided to do this book, I used to listen to those or watch them on youtube. Just kind of for the sheer outrageousness of it. They’re definitely the best examples of Lou Reed being an asshole. In terms of interviews on the opposite spectrum, where he’s being cooperative, I think that 1976 Hit Parader interview with Lenny Kaye is good.

The thing that I always got bored with, I remember when albums like New York came out, he just wanted to talk about guitar sounds and guitar tones and his favorite amplifiers. Basically, a lot of his interviews started reading like Guitar Player interviews.

He also started doing that with Tai chi for a while. In fact, one of the weirdest things I ever saw a major artist do, is I saw Lou play at the Warfield [in San Francisco], I would say, early 2000s. In the middle of the concert, he brings his Tai chi master out. And the guy just sort of does interpretive dances in front of the band, on stage where the audience can see, while they’re playing some Lou Reed songs.

It was kind of that nerd thing that I mentioned earlier in this interview. When he got fixated on something he really got fixated. A lot of these artists are kind of OCD, they’re obsessive compulsive, and they get fixated on something. It may be music, or it may be, what gauge guitar strings does Lou like to play?

When most fans, myself included, think of Lou and these interviews, you do think of things like those outrageous Australian interviews, or the Lester Bangs stuff. I hope when people read this book, they realize that Lou could be thoughtful, he could be nice, he could be insightful. And I hope that the book shows some of that side.

Like some magazine asked if they could print some excerpts of Lou’s quotes from the book. I went through and found what I felt were some of the more insightful things. And then, sort of behind my back without asking me, the editor of that particular magazine went through and just grabbed all the asshole-y soundbites. I think this book hopefully kind of shows both sides of Lou, the crazy soundbite stuff as well as, Lou’s being normal or gentle.