The relationship between Monty Python and rock music is pretty well known, in part because their first two movies probably wouldn’t have gotten made without investment from big rock stars. In particular, George Harrison’s Python fandom, and financial backing of Life of Brian, might be known even by some people who aren’t fans of either Python or the Beatles.

For all its significant role in their career, though, rock music itself wasn’t often used or even satirized too often in Python’s actual comedy. A rundown of the sketches in which rock played a part isn’t too hard to cover in one blogpost, though rock’s influence on the troupe predated Monty Python’s formation.

A good four years or so before Monty Python’s television series began broadcasting, Michael Palin hosted (or “presented,” to use the British term) a television show called Now! Based in the English city of Bristol, and done for the independent UK television network Television Wales and the West, it featured both sketches and appearances by British pop acts.

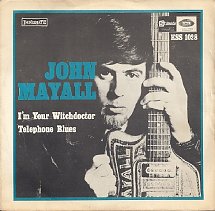

“Some of the groups we had on were very good—the Yardbirds, the Animals, Them, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers—some of them were very bad,” remembered Palin in the oral history The Pythons: Autobiography By the Pythons. “In fact, most of them were very bad, but that show gave me a financial cushion which ran from October /November ’65 until it finally petered out in May/June of ’66.”

This in itself is very interesting, as Palin sometimes played unctuous TV hosts on Monty Python sketches, and it’s a little hard to imagine him playing it relatively straight. What would be yet more interesting is being able to view some episodes, if any survive. I doubt it, in part because I couldn’t dig up any online, and I’ve never seen any bits excerpted in documentaries.

Palin didn’t specify whether the rock spots were mimed or live, but those would be especially interesting to view, especially if they were live (though I wouldn’t count on that). Even if the Yardbirds, Them, Animals, and Mayall were the only good acts on the program, those clips alone would make it worth sifting through the episodes. To my knowledge, there aren’t any surviving film clips of note of Mayall before 1968, which would make those especially worth seeing.

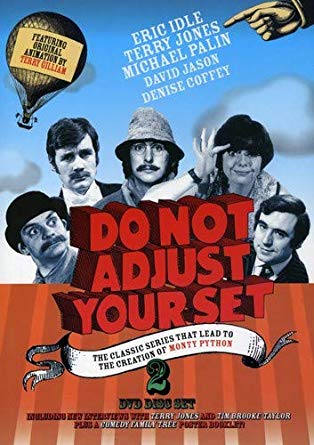

Palin, Eric Idle, and Terry Jones worked together closely as cast members of the British TV show Do Not Adjust Your Set for about a year and a half starting in late 1967. The Bonzo Dog Band did frequent guest spots, often involving performances of complete songs. While they were by no means among the hardest rocking of late-‘60s British bands, they were the best at blending music and comedy, and if the music owed more to vaudeville at their outset, soon much of their material had a rock base.

The most musically accomplished member, Neil Innes, would eventually because an auxiliary member of Python. He participated in their live shows, where he’d sometimes sing original satirical songs); took bit roles in the fourth year (the one without John Cleese) of the Python series; and had small roles in their first two movies. About twenty years ago, I asked him for his take on whether the Bonzos influenced the Pythons.

“There is a link,” he responded. “When the band first met Eric and Mike and Terry, there was a certain mutual suspicion, ‘cause we were crazy guys just coming off the road. They’d come from Oxford and Cambridge, and were young, up-and-coming writers; they’d written stuff for David Frost. It was a kind of cross-fertilization that took place over a couple of years. We all became very good friends.

“I think Eric’s acknowledged that there was an influence from the Bonzos in terms of the anarchy. Python wouldn’t have been Python, I think, if a lot of them hadn’t worked with the Bonzos. I’m not saying that the Bonzos taught them everything they know. But we certainly had the anarchy ingredient, which I think they found attractive, or useful to them. But they were more disciplined than the Bonzos. They knew how to get cameras to point at things.”

The Bonzos had also guested in the Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour, where they performed “Death Cab For Cutie” in the nightclub scene. While Monty Python had yet to have that kind of direct contact with the Beatles when they formed in 1969, they were of a similar age. At least some of them, like uncounted members of their generation, were huge fans. Here’s Palin, again from The Pythons: Autobiography By the Pythons:

“When we were writing in the late ‘60s, the Beatles were producing their albums and as far as I was concerned those were the greatest and most exciting examples of pop music around. On the day when we knew an album was coming out we just queued up to get it. The Beatles ruled the world, they were multi-millionaires, we were struggling away as comedy writers. Then I heard that during the first series Paul McCartney would stop his music sessions when Monty Python was on so that everyone could look at the show, and then they would go back to recording. That was the first moment I can remember when I thought, ‘This is extraordinary, the Beatles interested in us?’

“The other story, which I have no reason to dispute, was that George Harrison says he sent a congratulatory note to the BBC after the first show and it never got through to us, probably the BBC reception didn’t know who this Harrison man was, or what the program was or something. So right from the very start there was this connection between the best band in the world and our little band of comedy thesps.”

In the same book, Eric Idle enthused, “There was a big change in England brought about by the Beatles. Where everybody had been wearing tweed jackets with leather elbows, suddenly we were wearing leather jackets, and it was cool and you’d discuss your favorite George solo and things like that. That really made a difference and that kept going throughout the ’60s until glam rock, at which point you went ‘Oh, fuck off.’ You’d think ‘I don’t have to keep buying these records any more,’ because that used to be an event for us. Going down and buying the new Beatles album was something I did with [fellow British comedian] Tim Brooke-Taylor. We were quite mature men but still excited to go and buy the new Beatles album, even when we’d left Cambridge and were working for the BBC.”

So the Monty Python-Beatles mutual appreciation society was well underway almost from the story of Python’s TV series. Yet the core of that series — the 39 episodes, broadcast from late 1969 through early 1973, that included John Cleese — seldom employed or drew upon rock music, though it did often feature musical performances by the troupe. Why was that?

Maybe the other Pythons weren’t as big Beatles and rock fans as Palin and Idle. But also, their primary musical experience, such as it was, was in theatrical productions. None of them had been in rock bands. Performing and writing mock-musical pieces—which they did very well—would have come much more naturally than mimicking rock bands, which they never tried (though one would, famously, be a part of one of the most famous fictional rock bands about ten years later). I can only think of a few instances where rock, or even faintly rock-related pop, played even a small part in one of the Cleese episodes:

In episode thirteen, a psychiatric patient has auditory hallucinations of Julie Felix singing Tom Paxton’s banal kids’ song “Going to the Zoo.” A mediocre American folk singer somewhat in the Joan Baez mold, Felix would have been very familiar to British listeners/viewers, having achieved a fair amount of recognition after moving to the UK. She would have actually been more familiar from her appearances on television—including residency singing on the David Frost-hosted Frost Report and then hosting her own BBC TV series—than for her records, most of which weren’t big sellers, though a few made the British charts. “Going to the Zoo” was the title track to her 1969 album.

In the sketch, the patient gets taken in for an operation to get rid of his musical hallucinations. When he’s opened up, hippies emerged who’ve been squatting in his body. If you’re thinking this must be funnier on screen than reading about it, well, not that much. Even as a huge Monty Python fan, this struck me both at the time and since as one of their weakest sketches.

Moving ahead to episode 24, one of that program’s sketches presents a public service film on “how not be seen,” in which several people who are unsuccessful at hiding are blown up. The episode ends with “Jackie Charlton and the Tonettes” “performing” the Ohio Express’s “Yummy Yummy Yummy” in packing crates, so as not to be seen. It’s the actual Ohio Express bubblegum hit that plays, and that would have been familiar to both US and UK audiences, since it was a Top Five hit in both countries in summer 1968.

The Jackie Charlton reference, however, would only be picked up by British viewers. He was a well known British soccer (or “football,” as the sport’s known there) player, and managed the Irish national team at the 1990 World Cup finals. Not something that would be of much interest to Americans then or now.

The same episode had a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it zinger that was the best of the few rock references the Pythons wove into their scripts. A few men on the street offer absurd thoughts on peace (a gumby: “Basically, I believe in peace and bashing two bricks together”). Eric Idle, impersonating John Lennon (down to his Liverpool accent), chirps in: “I’m starting a war for peace.” A great six-word encapsulation of early-‘70s just-post-Beatle Lennon, engaging in peace activism while bashing Paul McCartney, George Martin, and lots of other things in interviews and songs, especially on his Plastic Ono Band album and marathon Rolling Stone interview.

Episode 28 ends with an appearance by an actual Beatle, though not Lennon. The tramp-like “It’s” man, regularly portrayed by Michael Palin throughout the series, is hosting a TV show with Lulu and none other than Ringo Starr as guests. After being briefly complimented by Lulu on his outfit, the end credits scroll and the Monty Python theme blares, the guests walking off in dismay.

According to Kim “Howard” Johnson’s The First 20 Years of Monty Python, the script actually called for John Lennon and Yoko Ono to be the guests. That changed to Starr and Lulu, Palin told Johnson, because “Ringo was the most extroverted of the Beatles, other than Lennon—he’s just that sort of guy. He’ll do anything that’s a bit silly and mad. He’s very nice and uncomplicated and easygoing.

“We wanted someone incredibly famous, and to get a Beatle at that time—we couldn’t get much higher than that. The others were all going through various sorts of withdrawals after the Beatles split up, and had their own particular egos, whereas Ringo just used to knock about. Graham [Chapman] got to know him, and asked him along.”

What about the other guest? “God knows where we got Lulu,” Palin added.

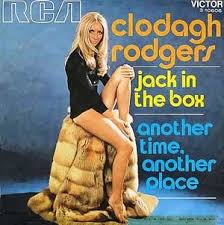

Episode 34 was, unlike every other one, not a series of sketches, but a single storyline, if one with silly and surreal turns. Palin played a goofy guy on a cycling tour who got into all sorts of comic misadventures. As a recurring sonic gag of sorts, Clodagh Rodgers’s bouncy, banal “Jack in the Box” is heard (and, sometimes, sung) throughout the program. The tune was the very embodiment of the kind of trivial puff heard in the Eurovision contest, in which “Jack in the Box” actually represented Great Britain in 1971. For that reason alone, it would have been extremely familiar to British audiences (and probably many other European viewers), the Northern Irish singer scoring a #4 UK hit with it that year. Alas, it and Rodgers would have been totally unknown to Americans, who could more or less laugh along with the gag anyway, fitting in as it did with the general silly fun of the episode.

Maybe an honorable mention should be given to a brief sketch in episode 5 in which a bumbling cop (Graham Chapman) tries to bust actor “Sandy Camp” (Eric Idle) for “certain substances of an illicit nature.” Chapman’s cop fumbles a brown paper bag out of his pocket so he can “take it with me for clinical examination,” only for Idle to discover it contains…sandwiches. “Blimey! Whatever did I give the wife?” exclaims Chapman. It’s an obvious spoof of suspiciously specious late-’60s drug busts of British celebrities, none of whom were more famous than John Lennon and George Harrison of the Beatles, and Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, and Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones. A few of those rockers speculated the drugs on their premises had in fact been planted by the police.

In his 2018 autobiography Always Look on the Bright Side of Life, Idle verified that when he first met Harrison in 1975, “George had assumed, probably rightly, that the sketch was based on his own drug bust in Esher, where the police had brought their own cannabis.” What’s more, in the same book he recalled how as a University of Cambridge student, “We bought black collarless Beatle jackets. We were first in line for their singles, we discussed our favorite Beatle, we adored A Hard Day’s Night.”

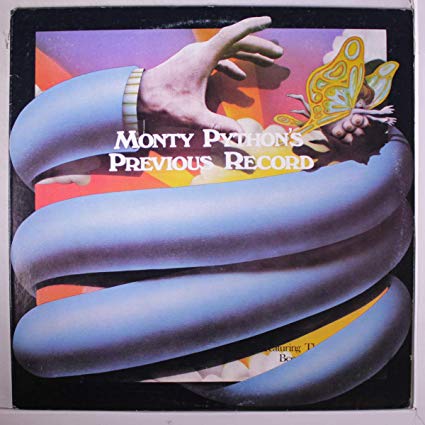

That’s it for rock in the TV series, and it wouldn’t be heard in Monty Python and the Holy Grail and The Life of Brian, which after all were mock historical epics that took place centuries before rock began. That wasn’t the end, however, of rock’s role in the life of Monty Python. Actually, a record label known mostly for rock acts (Charisma, who had its biggest success with Genesis)) had already done its part to supplement the Pythons’ presence with pretty popular Monty Python audio LPs. Back to Michael Palin in The Pythons: Autobiography By the Pythons for more:

“Gradually one began to hear more and more stories about bands and musicians who loved Python and felt a kinship with Python for some reason or another. I’ve never quite worked out why that was but there were more and more instances of it and you would meet musicians who would say, ‘That was just wonderful’ or ‘We love that show.’ I think they thought it was somehow quite cool, it was a cult thing.

“When it came to financing Monty Python and the Holy Grail, who came in but Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd as investors; the label on which we did most of our albums was basically a rock and roll label, so we were closely intertwined with rock music from very early on. But the fact that the Beatles noticed us was quite something. Almost as epic as when I read much later on that, in the declining years of his life, Elvis himself watched Monty Python and the Holy Grail.” Genesis and Jethro Tull also invested in the film, and more famously, George Harrison’s Handmade Films company financed Life of Brian after EMI Films pulled out.

As a relatively little known footnote, there could have been a close relationship between Monty Python and the Holy Grail and a much less successful actual Beatles movie. As Palin wrote in his diary on January 10, 1975:

“It was suggested at a meeting late last year that we should try to put out the Magical Mystery Tour as the supporting film to The Holy Grail. There was unanimous agreement among the Python group. After several months of checking and cross-checking we finally heard last week that the four Beatles had been consulted and were happy to let the film go out. So today we saw it for the first time since 1967. Unfortunately, it was not an unjustly underrated work…”

As much as it might have pained them in some ways to turn down the opportunity, the Pythons made the right call. The Holy Grail is a flawed but overall great film; Magical Mystery Tour is a terribly flawed and pretty terrible film (which pains me to note myself, as I’m a huge fan of both the Beatles and Python).

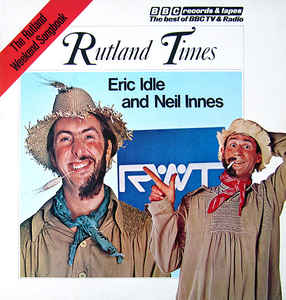

All of the Pythons did plenty of solo projects, but just one would draw notably on rock, and indeed use rock as the core focus of the best Python solo product. Eric Idle had already featured some occasional rock satire in his TV series Rutland Weekend Television, especially on spots by Neil Innes lampooning Elton John, Bob Dylan, and others. George Harrison also appeared in one Rutland episode, playing the entry to “My Sweet Lord” before gleefully segueing into “The Pirate Song,” which he co-wrote with Idle. Rutland Weekend Television was not picked up for US broadcast, and its thirteen mid-‘70s episodes have seldom been seen by Americans.

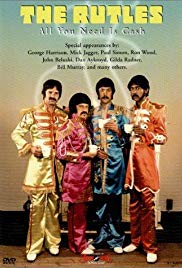

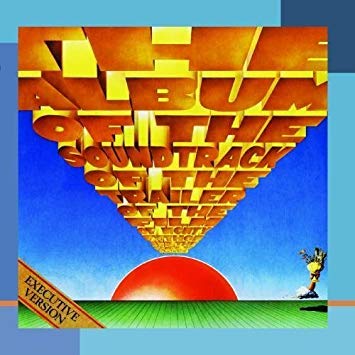

However, one Rutland Weekend Television sketch would not only be widely seen in the US, but lead to a full-long TV special. Hosting Saturday Night Live, Eric Idle screened a Rutland clip of the Rutles, brilliantly spoofing the Beatles circa A Hard Day’s Night. That helped lead to the US TV special All You Need Is Cash, where the Rutles brilliantly spoofed the Beatles’ entire career. Idle himself played the Paul McCartney-type Rutle, though he (unlike the other Rutles) didn’t actually play or sing the witty Beatles pastiches on the soundtrack, penned by Neil Innes (who played the John Lennon-type Rutle).

Along with Spinal Tap, All You Need Is Cash is the best mock rockumentary. It took a long time, and just one Python and an auxiliary Python were involved. But Monty Python and the Beatles had finally fused, the result—unlike almost all other such combinations that promised more on paper than the screen—taking from the best of both worlds.