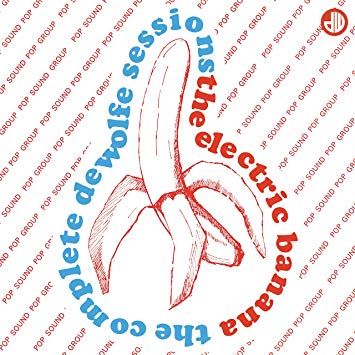

This fall sees the release of a three-CD set, on the UK Grapefruit label, by “the Electric Banana.” Titled The Complete de Wolfe Sessions, the recordings were used as incidental music for film soundtracks of the era. They might have vanished into total obscurity had it not been known that the musicians supplying this material were not just anonymous session players. They in fact comprised a pretty well known band, the Pretty Things.

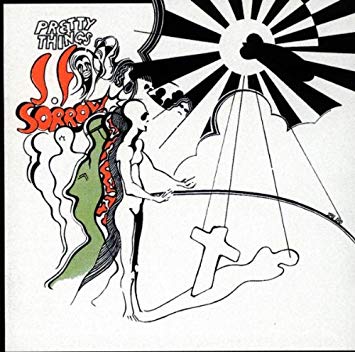

Besides being the best British group of the ‘60s not to make it in the US, the Pretty Things had an odd and colorful career. Most stories about them focus on their failure to tour the US as the oddest twist in their tale. Odder still, however, were these soundtrack recordings (sometimes termed “library music” in the UK), which no other group made as much of a sideline, if they ventured into this territory at all. If they hoped to keep their true identity hidden, the cover was blown pretty quickly by the presence of a spare version of “I See You” on the 1968 More Electric Banana LP. With much fuller production, it would be redone on their 1968 psychedelic album S.F. Sorrow.

Those hoping for a wealth of thrilling supplements to the core Pretty Things discography will be disappointed by the Electric Banana recordings. The group really were saving their best songs for S.F. Sorrow, 1970’s Parachute, and a couple creative flop psychedelic singles in 1967 and 1968. Much of what they were doing for the de Wolfe company was intended only as background music, to fit into scenes of movies that ended up a lot more obscure than even the Pretty Things’ rarer ‘60s releases. The extensive liner notes, while informative, coyly never cite the Pretty Things by name, as if there’s still a legal complication in acknowledging they were the guys behind these recordings.

That’s not to say these tracks are wholly without merit, especially for Pretty Things fans. The different version of “I See You” is effectively haunting (and somewhat similar to the Bee Gees’ “I Can’t See Nobody”), and the guitar riffs of “Alexander” anticipate similar ones on S.F. Sorrow’s “Balloon Burning.” Three of the songs also show up in different versions on the peculiar late-‘60s demo LP done with Philippe DeBarge on vocals (more on which later). Even More Electric Banana’s bittersweet, eerie instrumental “Dark Theme” is atmospheric dreamy psychedelia, and unlike these other cuts was not placed on the most widely available compilation of late-‘60s Electric Banana highlights,The Electric Banana Blows Your Mind. In all that would make a fair EP, the hard-charging harmony-pop-psych “Alexander” in particular becoming a fan favorite despite its relative obscurity.

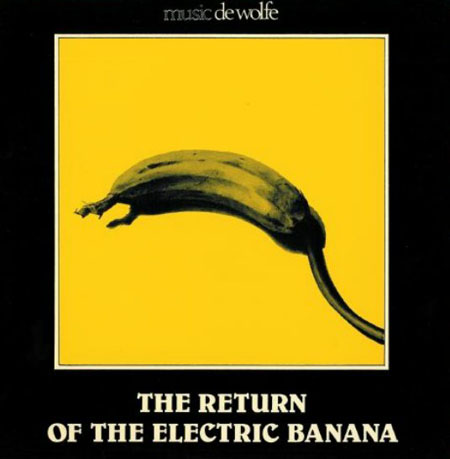

But the rest is pretty trivial, some of the earlier efforts sounding like mediocre outtakes from their controversial 1967 psych-pop-with orchestration album Emotions. The post-1970 tracks get into turgid blues-rock, and the final de Wolfe album they worked on, 1978’s The Return of Electric Banana, was done long after their peak. A good number of the less celebrated cuts are instrumental versions of songs better represented by their vocal counterparts.

The Return of Electric Banana does offer a bit in the way of surprising detours from their usual average mid-‘70s rock that are surprisingly good, notably the almost Greek folkish “Whiskey Song.” But with an overflow of more forgettable background music and routine rockers, this is for the Pretty Things completist. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, especially as the original LPs are super-hard to find, and the music’s usually only been available since then on grey-area releases.

Even considering how inferior the de Wolfe albums were to the bulk of the Pretty Things’ studio work, it’s interesting to consider how they ended up making so many of these—five entire LPs between 1967 and 1978. I can think of no other band of note that made this as much of a sideline. Probably a number of bands, or at least musicians from bands with “real” albums, played on library music discs. But if any others did too much of it, it hasn’t come to light.

I posed this question to one of the most knowledgeable UK collectors I know, who responded that Jade Warrior—a British progressive rock outfit who put out a number of LPs in the early-to-mid-‘70s without gaining much sales—“made a library album, which virtually no one is aware of. Maybe just me and the band!” He added, “It was long claimed that the two London’s Underground library LPs on Conroy were by Hawkwind, but that is nonsense. They were actually by a band featuring rock journeyman Garth Watt-Roy.”

So were the Pretties producing a steady stream of these to make a quick buck? Yeah, pretty much. Asked point blank “did you record them only for the money?” in a 1985 issue of the Gorilla Beat fanzine, singer Phil May replied, “Yeah, because we needed money at that time to continue what we were doing. I mean, nobody gave us any money for S.F. Sorrow, we had it about pencil written, then [guitarist] Dick [Taylor] and I were quite broken at that time and we didn’t get large wages from the records.”

Asked Gorilla Beat, “Did they come and say: ‘Write the music for this or that sequence?” May responded, “Every time we made a record and felt we had some songs left over, the guys came into the studio and bought the recordings we didn’t need. These songs were used in films, television series and so on. We were earning good money. This helped us to stay alive, really. What happened was, somebody would ring up de Wolfe saying: ‘Have you got some music backing for us. We got a sequence in a bar where a gangster shoots down another gangster and there is a jukebox playing in the background. So, what can I have?’

“And so they used material from the Electric Banana LPs. So when you see the film, this guy walks into the bar and there’s this rock music coming from the jukebox, that’s the Pretty Things, and then it was quieten down in the dialogue and the guy shoots the other man and leaves. We did it as I said to stay alive, really.”

Other members of the late-‘60s Pretty Things are similarly offhand in their Electric Banana assessments. Observed Wally Waller in Alan Lakey’s bio The Pretty Things: Growing Old Disgracefully, “It was of that time, it was all kind of flower-power stuff, I don’t think they really stand up today to too close a scrutiny, that’s my opinion. I’m not a fan and I can’t see why people find that exceptional. To my mind we’ve done lots of good stuff but to my way of thinking that doesn’t get anywhere near the real cream. Most of that stuff is second rate. Some of it is all rightish but most is stuff we didn’t think was good enough to put on an album of our own and we wouldn’t put our proper name to it.”

In the same book, Jon Povey was yet more dismissive: “Yeah, don’t really want to talk about that too much. It was just purely to get some money.”

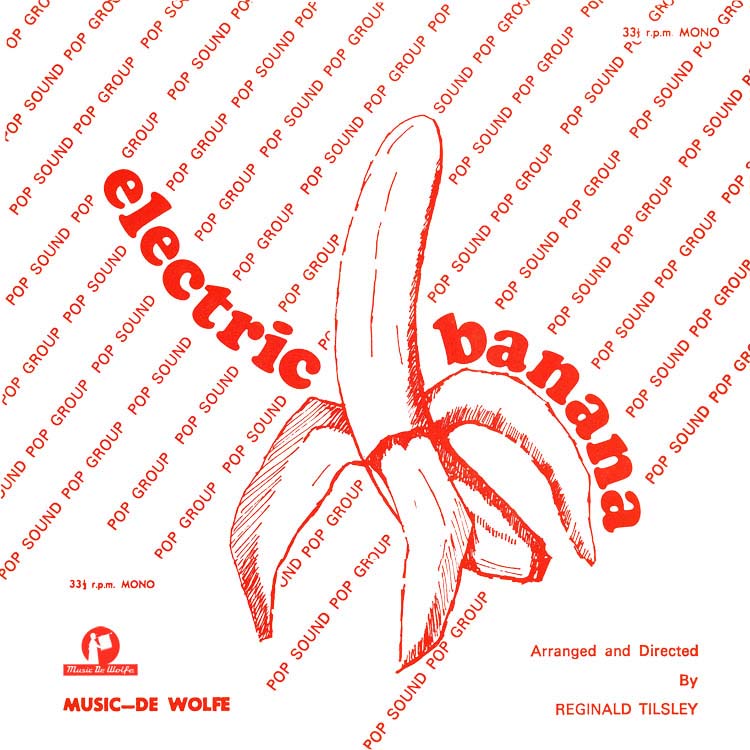

Also in that volume, guitarist Dick Taylor explained how the group ended up doing four songs by non-band member Peter Reno on the first Electric Banana disc, and why they were sung not by May, but by Waller and Povey. “When it was first issued they put out all the vocals on one side of the album, they were on ten-inch vinyl with quite plain covers with a drawn banana and diagonal writing. They weren’t meant for public release but it was in the music library and it was really breaking the rules at the time because we weren’t paid musicians union rates because we were getting money for the writing and stuff, so it was very unofficial.

“So if a film producer wanted something to go on his film he could either choose something vocal or something instrumental and you may have noticed there were some that weren’t written by us, and the guy was a TV producer and he wanted his songs on these albums. So in some of his shows he could use his own stuff and he saw it as a way of making a little bit of money on the side so that other producers would think, oh Peter does this. I presume that’s how it works. Anyway, that’s how it started with Peter Reno.”

As an example on one of the Reno songs, “Wally sang that. It was a bit like when we got ‘Rosalyn’[their first single, in 1964] it was Denmark Street [London’s equivalent of Tin Pan Alley] with a bloke pounding it out on a piano. These were similar, they sounded a bit sub-Matt Monroe [a British pop crooner]. It was like ‘Oh, what the fucking hell are we gonna do with these things?’ We just put whatever riffs we could muster up against it, changed the chords around a bit and turned it into what they then became.”

In The Pretty Things: Growing Old Disgracefully, Waller also indicates that at least some of the de Wolfe tracks were cut with extreme haste. “Everything was done in a small eight-track demo studio just big enough to swing a cat around,” he said. “If we had a de Wolfe session coming up we’d sit down and in an afternoon we’d thrash out the whole thing and we’d walk into the studio still fixing a few lyrics and in an afternoon the whole thing’s down. That’s the way it works. It’s almost like a telephone box the bloody thing was so small, that little studio we used. In the early days it was only four-track, it was like a demo down Wardour Street [in central London].”

For all that, Taylor acknowledged to Lakey that some items of true worth found their way onto the Electric Banana albums. “Funny thing is the things like ‘Alexander’ and all the stuff around then is actually some of the best stuff we did,” he remarked. “A lot of people have said to me you should go back to it, it’s really good stuff. It’s a bit like the way we’re so rigid in our condemnation of Emotions, you listen to it again and think hang on, we’ve missed the point here. Here we are slagging it off but there’s some good songs, some good stuff on there.”

Were there other significant acts of the time that took on projects mostly to make money, and that some might view as sellouts, or at least certainly peripheral to their main body of work? Sure. Uncounted artists from all walks of rock did commercial jingles, and not just the fairly superficial ones you might expect, like Petula Clark and Freddie & the Dreamers. The Rolling Stones (albeit very early in their career), the Who, and the Yardbirds did too. (Among their many distinctions, the Beatles did not.) Even Jefferson Airplane did an ad for Levi’s, and Sandy Denny for butter. Some psychedelic groups who had relatively little commercial success got in on the action, like H.P. Lovecraft when they sang for Ban deodorant.

Aside from the Pretty Things, the group that might have made soundtracks and such their biggest sideline were Manfred Mann. In various lineups (with Manfred himself always present), they made no secret of doing plenty of commercial jingles, and you can hear a few—including ditties for Michelin, Maxwell House, and yogurt—on the recent compilation Radio Days Vol. 3: Live Sessions & Studio Rarities. They also did a full soundtrack—one specifically designed to be used as part of a dramatic feature film in which they didn’t appear, unlike the music heard by the Beatles, Elvis Presley, and many others in movies in which the artist actually appeared—for 1968’s Up the Junction.

It’s fair to say the Manfreds approached that fairly well regarded soundtrack with more seriousness than the Pretty Things did for the Electric Banana projects. It’s not nearly as well known that Manfred Mann contributed to a couple of far more obscure, exploitation-bordering flicks. They (well, really just Mann and Mike Hugg) did the soundtrack for the 1969 American International Pictures sexploitation movie Venus in Furs, which has no relation to the Velvet Underground classic of the same name. That’s also included on Radio Days Vol. 3: Live Sessions & Studio Rarities, though with lo-fi sound, the original tapes presumably being unavailable. It’s an eerie mix of avant-garde horror and downbeat jazz, though in common with many a soundtrack, there are too many repeated motifs to make this something likely to get many spins.

Mann also co-produced the soundtrack to the early-‘70s softcore production Swedish Fly Girls, as well as contributing some music. That soundtrack’s also notable for including a few cuts sung by…Sandy Denny, who wasn’t beyond taking on some studio sessions outside of her usual folk-rock efforts. Rock musicians didn’t make a whole lot of money if they weren’t big stars, and every bit helped. In perhaps the most famous instance, shortly before breaking through with his first hit, Elton John sang on numerous soundalike cover versions of hit records made for budget LPs in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s; many of those performances were compiled on the Chartbusters Go Pop CD.

Maybe the closest parallel to Electric Banana, in terms of a well known group creating soundtrack recordings for use in productions few rock fans saw, was the Doors’ creation of incidental music for, of all things, a Ford training film geared toward improving the customer service by employees at its sales outlets. Aside from the periodic washes of instrumental music (there’s no singing or evident participation by Jim Morrison) it’s a positively excruciating 25 minutes, in line with the skeletal production values and dated do-gooder ethos of industrial training movies.

There’s a crucial difference between the Doors’ and the Pretty Things’ soundtracks, however. The Doors did this before they had a record deal. The Pretty Things had already made numerous singles, a couple of them big hits in the UK, and a few albums before hooking up with de Wolfe. Like the Pretties, the Doors did use a bit of riffage in the soundtrack that resurfaced on their proper records. At a bit near the end of the training film, they go into a passage similar to the tune of a song on their great 1967 debut album, “I Looked At You.” The movie’s easily accessible now as an extra on the Doors’ Re-Evolution DVD, which primarily compiled their promo films and TV appearances.

There are also numerous instances throughout rock history of an artist recording under a pseudonym, whether as a joke, as a sideline project, or to hide their true identity when they took part in a budget or exploitation project. The Four Seasons had a hit as the Wonder Who by covering Bob Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright,” though lots of people guessed the group’s identity after hearing a few seconds of Frankie Valli’s inimitably high, screechy vocals. In more recent times XTC took the Dukes of Stratosphear name for an EP of retro ‘60s psych. There are examples with far cultier groups, like the Chocolate Watchband posing as the Hogs on the early psychedelic novelty “Loose Lip Sync Ship.”

Back to my British friend for more examples from 1960s and early 1970s known primarily in the collector world, and not even that widely within that: “Egg (or Uriel, as they were then) made the Arzachel LP for a quick buck, and later played on a Decca cash-in LP called The World Of Heavy Hits. Members of Savoy Brown and Foghat posed as Warren Philips & the Rockets for another. Members of Spice/Uriah Heep posed as ‘Head Machine’ for the Orgasm album.”

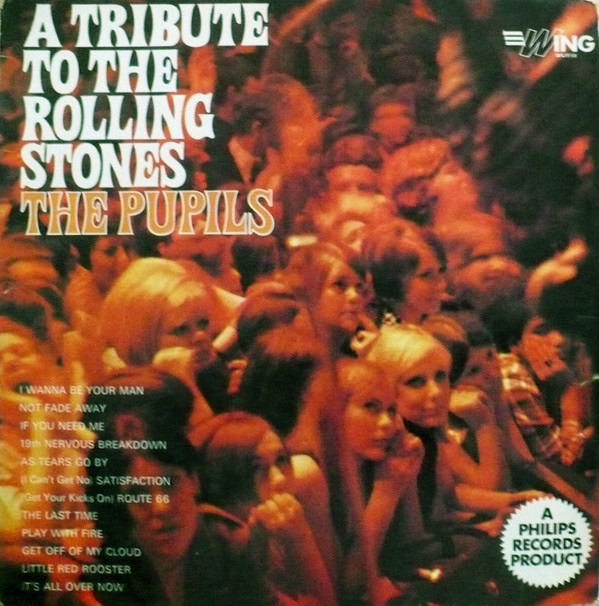

Back in the British Invasion days, also-ran Liverpool group Ian & the Zodiacs posed as the Koppycats on a couple budget exploitation albums of Beatles covers. Weirdest of all, the Eyes, a good mid-‘60s British mod group that never had a hit, put out an LP of Rolling Stones covers as the Pupils. They never got to do an album as the Eyes, and one thinks it must have hurt when they had to play exploitation covers on their only opportunity to make a full-length record.

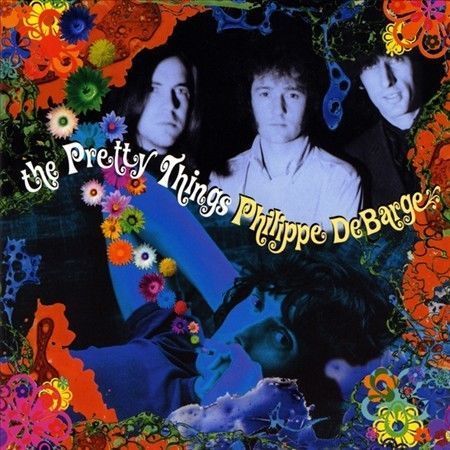

The Pretty Things never had to stoop that low, but the Electric Banana exercises weren’t even the end of their late-‘60s extracurricular activities that were taken on primarily to generate some cash. In 1969, they were the uncredited band backing French singer Philippe DeBarge on an unreleased album exclusively devoted to originals by May and Waller. It’s a peculiar record of decent, but not stunning, pop-psychedelic material, especially since May doesn’t sing on it at all, though he co-wrote everything. Why would you essentially record a Pretty Things album without vocals by the lead singer?

Philippe DeBarge, the title given the album when it was issued on CD in 2009, was kind of a vanity project on the part of Mr. DeBarge. A big Pretty Things fan, he paid for the sessions, essentially for the privilege of being a part of the group in the studio, probably in hopes that he could find a deal for the LP’s release. He was even did a few versions of the best songs from Even More Electric Banana, including “Alexander,” “Eagle’s Son,” and “It’ll Never Be Me.” He wasn’t the worst singer, but he was no Phil May, or particularly distinguished in any respect.

May was diffident about the project when I interviewed him for the Pretty Things chapter in my book Urban Spacemen & Wayfaring Strangers: Overlooked Innovators & Eccentric Visionaries of ‘60s Rock. “Wally and I just wrote a bunch of songs for this French millionaire,” he told me. “No kind of falseness about, ‘he was a musician.’ He just wanted to make a record with the Pretty Things, and he was prepared to pay.”

Added May in Mike Stax’s liner notes for the Philippe DeBarge CD, “I don’t think any of us had great expectations, but we didn’t approach it in that way. We approached it like it was another record to make, and we were getting stuff out of it for ourselves, apart from the finances. It was a good stepping stone between S.F. Sorrow and Parachute.”

In the same notes, Waller also acknowledged the sessions had some value. “For me it was a chance to be the boss in the studio for the first time. I had always been really involved with the production process on all our albums. And I just loved to have the chance to write a few songs and see them through to the end. I think the project put us in a much better shape to tackle something like Parachute.”

As for DeBarge, speculated Wally, “Quite what he was going to do with it I don’t know. I don’t think there would have been any interest from the British music industry, and being in English it wasn’t really suitable for the French market. I think it was a grand indulgence on Philippe’s part. To be honest I was not surprised that nothing became of it.”

We’ve gone through quite a few cases where groups took on extracurricular work that wasn’t part of their core resume, whether to keep their heads above water, float a few of their lower-priority ideas, or a combination of the two. There weren’t, however, many other albums you could name where a well known, or at least pretty well known in the Pretty Things’ cases, group was engaged to be the band for a vanity project like this. Maybe Bob Markley, the benefactor of the West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band, counts in a way, since the only way a man with such minimal musical talent could take part in those records as a quasi-member was by helping to bankroll the whole enterprise. But the LPs by that group in which he took part were a part of that act’s core resume, and Markley, unlike DeBarge, did write some of the material.

In helping to keep the Pretty Things going, the Electric Banana and Philippe de Barge recordings served a larger purpose. Had they not been made, the band might not have even been around to record S.F. Sorrow and Parachute, two albums of psychedelic/progressive rock that took quite a bit of effort to construct in one of the top studios in the world, Abbey Road. While I don’t know how many copies those LPs sold, they weren’t hits (though Parachute did make #43 in the UK charts), and I doubt if they made much or any money. If they had to do these extra-Abbey Road gigs to make sure their real albums were completed, those are nothing they should be ashamed of—and some real good music did escape on those other records as well.