As we get on in the 21st century, boxed sets are appearing that would have seemed unimaginable even ten years ago, let alone pre- CD era. The Cherry Red group have been at the forefront of this, whether it’s a four-CD set on a cult band that never put out an LP (the Action) or triple CDs on obscure corners of UK late-‘60s/early-‘70s folk-rock. Still, I never expected there to ever be a three-CD set for the Honeycombs, which appeared early this year on Cherry Red’s RPM imprint.

The Honeycombs are often thought of as a one-hit group, particularly in the US, where their 1964 stomper “Have I the Right” was their only high-charting single (though another, “I Can’t Stop,” fell not too short of the Top Forty). It made #5 in the States in 1964 when the British Invasion was gathering unstoppable steam, and #1 in their native UK, where they did manage to land another Top Twenty entry with “That’s the Way.” Along with the Tornados’ 1962 instrumental chart-topper “Telstar,” it was the only production by the legendarily eccentric Joe Meek to hit big in the US, though Meek was some other hits (and numerous notable and not-so-notable flops) in his native Britain.

Because of the peculiar compressed crunch of “Have I the Right,” its eerie high-pitched male vocal, and the presence (very rare in ‘60s rock) of a woman drummer, the Honeycombs have sometimes been kind of dismissed as a gimmicky fluke act. That’s especially the case since, unlike most notable British Invasion groups, they wrote almost none of their material, most of which was composed by their managers and (more occasionally) Meek. They projected little in the way of image, other than the immediately distinctive visual trademark of a woman drummer. What relatively little has been written about them doesn’t lend much insight into the group’s musical motivations and aspirations, even in the 24-page booklet of liner notes in this new anthology.

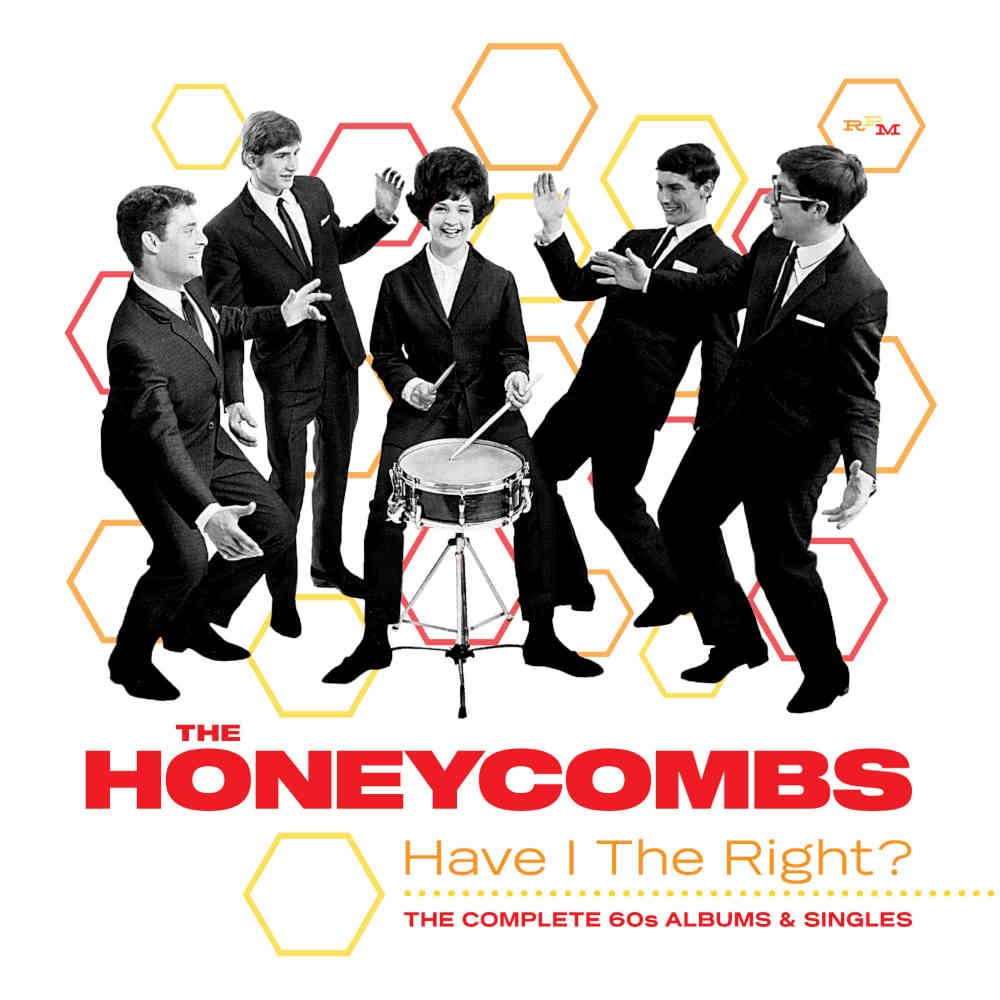

Yet the Honeycombs recorded a lot more than most people realize, even among British Invasion fans. Have I the Right: The Complete 60s Albums & Singles has 79 tracks, including their three albums. Yes, they had more LPs than they had big US/UK hits. And they had a lot of non-LP singles: eight, which together with the decent non-album B-side of “Have I the Right” (“Please Don’t Pretend Again”) adds up to more than another LP’s worth of sides on their own. Throw in a German-language version of both sides of the “Have I the Right” single; a couple songs broadcast on 1965 radio programs of uncertain origin (the bass on the radio take of “That’s the Way” is unexpectedly powerful, by the way); five previously unreleased studio outtakes; and some post-Honeycombs solo singles from singer Denny D’Ell and original guitarist Martin Murray, and you have enough to fill almost four hours.

Wise guys would counter that’s almost four hours too many, but in fact, there’s a fair amount of really good material here, almost all of it virtually unknown beyond Meek geeks. There’s a lot of silly, even puerile stuff too. Not infrequently, those qualities are mixed together. Their body of work is among the most peculiar of any ‘60s group to make a significant mark on the rock world.

If you’ve gotten this far, you’re almost certainly familiar with “Have I the Right,” the one song that’s familiar to almost everyone in the UK and North America. Many of its attributes (some would say annoyances) are found throughout their records. Dennis D’Ell had a weird, whiny waver of a voice that could sound like Gene Pitney speeded up from 33 to 45. (Maybe that inspired Brian Jones, as has sometimes been reported, to call an Australian radio station while on tour Down Under to play the disc at 78.) Whether played by Honey Lantree or reinforced by the other Honeycombs and other feet and hands, there was often a floorboard stomp to the rhythm, perhaps influenced by the then-huge success of the Dave Clark Five.

As with many Meek productions, there was an eerie almost outer space shimmer to the hissy compression and sped-up-sounding vocal and instrumental tones. Less noted—actually, I’ve never seen it noted—was the distinctive piercing, curling, needle-prick guitar, which like D’Ell’s voice often teetered on the edge of the note. Since similar spooky guitar is heard on some other Meek productions, it wouldn’t surprise me if the producer manipulated the sound of the instrument in the studio.

Honeycombs managers Ken Howard and Alan Blaikley were responsible for writing the bulk of the group’s repertoire (though they’re more famous for doing the same thing a bit later for Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick & Tich, who had a long string of UK smashes without breaking through in the US). Even by the standards of early British Invasion lyrics, their Honeycombs songs were twee in the extreme. Early Beatles songs like “Love Me Do” might have banal words on paper, but they were delivered with sincerity and soul. The Honeycombs bore, in keeping with their name, rather sickly sweet sentiments, accentuated by a voice (D’Ell’s) that almost seemed about to run away and hide in the corner out of nervous embarrassment.

What saved the best of their recordings—indeed, sometimes made them exhilarating—were of course the production, but also some haunting melodies, surprisingly effective unearthly background vocals, and a certain sense of manic ebullience that transcended the source material. Sometimes “deep” Honeycombs cuts could be surprisingly spooky, like soundtracks for walks through a moonlit cemetery. From their first LP, “Without You It Is Night” and “This Too Should Pass Away” (both enhanced by ethereal organ) certainly qualify on those grounds, even if the songs are pretty much alike. The non-hit single “Eyes” is too, building to a suspenseful climax and perpetually restless in its key shifts and fractured waltz tempo.

“Something I Got to Tell You” (buried on their second LP, 1965’s All Systems Go!) was, along with the bouncily innocuous “That’s the Way,” the only song on which Honey Lantree sang lead. With a fairly pleasing and far more conventional voice than D’Ell’s, she was underutilized in this role, and “Something I Got to Tell You” was more mature than most of songs that surrounded it. But still spooky, with its pensive melody and, more notably, faint swirling backup vocals that seem to have floated up from the bottom of a fish tank. This sounds like it just could have been a hit, but its prospects probably would have been doomed by the unusual use of “hell” (“something’s giving me hell, baby”) in the lyric, which was rarely heard on AM radio in 1965. A far more chipper, and much inferior, version was produced by Meek for another of his clients, Glenda Collins.

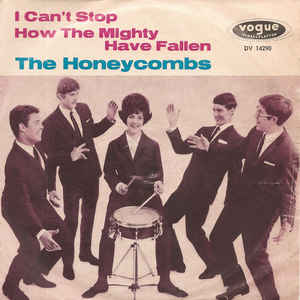

The Honeycombs’ finest moment, however, was “I Can’t Stop,” a US-only follow-up single to “Have I the Right” that actually made it up to #48 in the American charts. With infectious stop-start stomps, downward glissando sweeps, and nearly crazed yelps and screams, it was one of Meek’s finest productions, though I’ve never seen it hailed as such elsewhere. Such was its idiosyncrasy that even though I heard it on oldies radio just once as a young adolescent in the mid-1970s, I never forgot it.

Warning: the version of “I Can’t Stop” on All Systems Go! is an entirely different remake, and a ghastly one. I can think of no other remake done relatively shortly after the original that is so inferior. Everything about the 45 is right; everything about the LP counterpart is wrong, plodding around without the vocal yelps, glissandos, machine-gun drumming in the bridge, punchy sonics, or general sense of out-of-control euphoria. I keenly recall my disappointment at finally finding the track on a best-of LP around the late 1980s, and my horror when realizing I was hearing a poor substitute. Its existence (especially as it’s the first cut on All Systems Go!) is inexplicable, though a fellow collector speculated the original wasn’t used as guitarist Martin Murray left the band in December 1964 under somewhat less than amiable circumstances, receiving a substantial cash settlement. “I Can’t Stop” might have been redone so Murray wouldn’t get paid for a performance by a different lineup.

Getting back to the Honeycombs’ catalog, another highlight is All System Go!’s “Love in Tokyo,” with its otherworldly electronic keyboard glow and typically spectral Howard-Blaikley tune. Alas, another warning is needed: the version on the new CD box has a defect, skipping a whole second (which includes part of a vocal) around the 22-second mark. So for all its breadth, this three-disc comp is still the Incomplete 1960s albums and singles, if only by the slimmest of margins. (The original, defect-less version did appear on the expanded All System Go! CD on Repertoire in 1990.)

Yet another warning: the second LP was coveted by some non-Honeycombs fans for its inclusion of a rare Ray Davies composition the Kinks never recorded, “Emptiness.” But—in common with most of the songs great British Invasion bands like the Beatles, Rolling Stones, and Who “gave away” for other acts to do—it’s not that good, and certainly not in the same league as what the songwriters were holding back for their own groups. The Honeycombs also tried one of the Kinks’ better early songs, “Something Better Beginning,” though the Kinks’ version is way better.

Back to more positive notes, a good number of Honeycombs tracks—the majority, I’d say—have something to recommend them in the way of odd production and appealing strange melody, even if a good number of these are kind of variations of a formula. An obscure standout is their final single (from September 1966), “That Loving Feeling.” Almost sounding as if the group’s fighting to be heard from behind a closet in its dense compressed clutter, it also has the feeling of a band sensing their end is near. That’s not referred to at all in the lyrics, but there’s a desperation to the gloomy melody and combination of lead and backup vocals, as if the group knows the time for their sound is fast running out.

That same vibe also comes through in a more muted way on the B-side, the Meek-penned “Should a Man Cry,” with an unexpectedly guttural fuzzy guitar solo. Time really was running out for Meek. The Honeycombs might have ended their recording career, but they didn’t die. Meek did in on February 3, 1967, killing himself after shooting his landlady.

In a different way, however, “That Loving Feeling” could have pointed to the future. It was one of just two original compositions the band managed to release, the other being the Murray’s lightweight “Leslie Anne” on their debut LP. “That Loving Feeling” was the work of Colin Boyd, part of the much-altered lineup of the Honeycombs’ final year or so. Boyd also wrote two neat (and yet more muffled-sounding) outtakes that make their first appearance on this compilation, indicating he could hit the right kind of haunting Honeycombs tone with his compositions had he been given more opportunities. “Tell Me Baby” in particular has the kind of mix of melancholy and exuberance heard in some of their best material, with a somewhat more mature air than Howard-Blaikley’s ditties. But that wasn’t to be, the group petering out not long after Meek’s death.

For all my enthusiastic championship of the Honeycombs’ work as worthy of reexamination despite its extremely unhip reputation, even a fan like me has to admit there’s a fair amount of guff in their discography. Some Howard-Blaikley constructions could be sugary in the extreme, starting with the leadoff cut from their first LP, “Colour Slide” (though that song does have its devotees). All Systems Go! has some treacly oldies covers, like their take on the Platters’ “My Prayer.” The rare Japan-only LP (issued in late 1965), In Tokyo (Live), is mostly comprised of mediocre covers of American rock hits. And the solo singles by Martin Murray (one, from 1966) and Denny D’Ell (two, from 1967) that close the box are undistinguished pop, and not produced by Meek. Who was going to listen to a cover of Bobby Vee’s “The Night Has a Thousand Eyes” in the summer of 1967, which D’Ell put on the B-side of his final 45?

Even after digesting this quite hefty box (and even though I already had most of the tracks elsewhere), some puzzles about the Honeycombs remain. How much of their records was down to Meek and Howard-Blaikley, and how much to them? There are few other hitmaking bands from the time that played their own instruments that seemed so dependent on their producer and a specific outside songwriting team for whatever distinctive sound they managed. How did they feel about the process, in which some might view them as mere vehicles for the others who did the creative grunt work?

Also: was Meek trying to do something particularly special for the Honeycombs in the studio, in contrast to his numerous other clients? Why were so many Honeycombs discs released in the wake of “Have I the Right,” including a second studio LP, at a time when even some UK groups with big hits never got the chance to do more than one longplayer in their home country? Why in the world wasn’t the single version of “I Can’t Stop” issued in the UK? How did the group’s early singles end up on the little known Vee-Jay subsidiary Interphon in the US—making the Honeycombs the only British group besides the Beatles to have American hits on Vee-Jay?

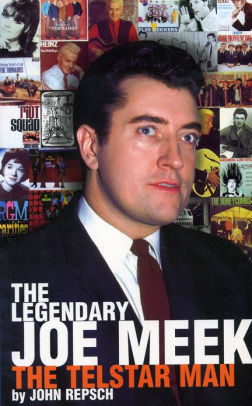

The sources that would seem most likely to contain some insight—the 24-page booklet of liner notes with this anthology, and John Repsch’s biography The Legendary Joe Meek—offer disappointingly little in that regard. The chapter on Howard-Blaikley in Johnny Rogan’s Starmakers and Svengalis doesn’t offer much either, but does contain this interesting passage:

“Reviving the chart fortunes of the Honeycombs proved immensely difficult, particularly as the group seemed relatively unconcerned about their status in the pop world. According to Howard, they preferred singing in pubs to appearing on television and reacted to their chart-topping achievement with humble satisfaction rather than awe-inspiring egomania. Their lack of ambition was also reflected in lackluster live performances which often ended in jeers from over-expectant members of the audience. In desperation, their managers temporarily sent them abroad where pop-starved fans were less discriminating.” (Indeed, according to the liner notes, much of their final year was spent in Israel.)

With some of the Honeycombs now gone and little interest in investigating their work among mainstream rock historians, we’ll probably never wholly know what made them and their team tick. Their story is in some ways as mysterious as their music.