I’m one of those people, apparently not too common, who goes through the extra features on DVD releases. Sometimes they’re good, sometimes they don’t really say or illuminate much, and sometimes they’re a waste of time. On the DVD release of the 2019 documentary David Crosby: Remember My Name, most of the deleted scenes, extended interviews, and Q&A with an audience aren’t too remarkable. But the two extra interviews are worth your time if you’re interested in Crosby, and in the Byrds in particular.

In the main movie that played in theaters, Roger McGuinn is only interviewed for a bit. The other surviving original Byrd, Chris Hillman, is only interviewed for a few seconds. Much of the coverage of the McGuinn-Hillman-Crosby relationship is relegated to a kind of contrived animation sequence recreating the incident in late 1967 when McGuinn and Hillman drove to Crosby’s house to fire him. The animation seems to fairly accurately depict what happened, but it’s a little strange considering that all three characters were available to talk about it on camera.

The McGuinn and Hillman interviews in the DVD extras—actually, they are the only interviews featured in the DVD extras—run about six minutes each. Here both of them are able to discuss their relationships with Crosby in more depth. Unusually for a documentary, their comments generally reflect better on both Crosby and themselves than what makes it into the film. It’s almost as though the filmmakers (and maybe Crosby) wanted to portray the subject in a worse light than he really was/is, whether to heighten the movie’s drama or for another reason.

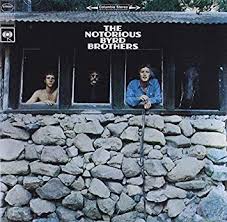

Much of the Byrds’ portion of Remember My Name focuses on the circumstances leading to Crosby’s departure from the group. This came to a head when David wanted to put his controversial song “Triad,” about a menage a trois, on their fifth album, The Notorious Byrd Brothers. The other Byrds didn’t want it on the LP, though the group did record the song, which is now available as a bonus outtake on CD. As is well known, Crosby’s friends Jefferson Airplane recorded it on their fourth album, 1968’s Crown of Creation, though Grace Slick’s made it clear it does not refer to a three-way from her personal experience.

McGuinn and Hillman favored other material, including one song Crosby especially didn’t like, the Gerry Goffin-Carole King composition “Goin’ Back.” For one thing, David felt the group should be emphasizing their own material, and perhaps Crosby’s songs in particular. But his dislike of “Goin’ Back” in particular seemed genuine.

As an aside, though several historical accounts authenticate this dispute, I couldn’t find a direct quote from Crosby voicing his specific opinion about “Goin’ Back,” though he’s discussed “Triad” and how he felt about its rejection on several occasions. Several other close associates of Crosby, however, have verified David’s distaste for the number. These include producer Gary Usher, road manager Jimmi Seiter, McGuinn’s first wife Ianthe (in her memoir), and, in his bonus interview, Chris Hillman. The explanations vary a bit, but basically state Crosby found the song too poppy and too sappy.

“David really hated the Carole King song,” elaborated Ianthe McGuinn (now known as Dolores Tickner) in an interview with me. “I know he thought it was insipid. I think that really was the catalyst [for his departure]. Certainly the Byrds evolved the song. They definitely improved on it. But I think it was the lyrics that David objected to. I think it didn’t have the bite that the other songs had had. I remember it like very fluffy, the ‘la la la la las.’ I can see why David objected to it.”

Most Byrds fans disagree with Crosby, and find it a fine interpretation in the classic Byrds folk-rock style, complete with ringing guitar riffs and luminous harmonies. It’s the best version of the song, though some prefer Dusty Springfield’s far more pop-soul-inclined interpretation.

Judging purely from what you see in Remember My Name, you might get the impression McGuinn and Hillman couldn’t stand Crosby and couldn’t wait to get rid of him. That might have been true the final months David was in the band, but in his bonus interview, Hillman spends far more time lauding Crosby than tearing him down. More than once, Chris emphasizes David had his back, especially back in the early days of the Byrds, when Hillman was the shyest member and considerably younger and less experienced than Crosby and McGuinn. He also reveals how he and his wife gave money to Crosby when David was getting ready for a liver transplant, and how David insisted on paying Chris back a year or two later, over Hillman’s objections. That, Hillman states, is the real David Crosby, behind the bluster for which his ex-bandmate’s most known.

Hillman does confirm, at greater length than the movie allows, that Crosby didn’t like “Goin’ Back.” “David hated it, wouldn’t sing on it,” Chris remembers. “I sang the harmony, not as good as the mighty Croz.” He also affirms the portrait of Crosby’s mindset in the Byrds’ final days: “He was not a contributing band member at that point. He was bored.”

The tension between Crosby and McGuinn seems greater than it was between Crosby and Hillman. If anyone was the leader of the band, Roger was, though David was threatening that position by 1967. But despite some harsh criticism that’s flown back and forth between them over the years, McGuinn has much glowing praise for Crosby in his bonus interview segment.

“David Crosby is the best harmony singer in the world,” Roger declares. “Singing with David Crosby….It’s just wonderful. He’s got the perfect sweet blend, especially with my voice.”

On top of that, McGuinn admits, “It was a mistake to fire him. To fire the best harmony singer in the world. It was the best sound we ever had vocally…never got that good again. We missed David. David was an essential part of the Byrds.”

McGuinn’s comments aren’t all peaches and cream. Although Crosby’s said he was told the remaining Byrds could make better music without him, Roger states he never said that, actually telling David the Byrds could make good music without him, which is a crucial distinction. McGuinn also notes that just as Crosby was kicked out of all of his schools, he was kicked out of all of his bands. David’s current long-running one is an exception, Roger believes, as he’s the leader who can be in control.

McGuinn probably speaks for many viewers when he expresses mystification at the termination of the close decades-long friendship between Crosby and Graham Nash, who are no longer even on speaking terms. “I’m so sorry to see the rift between David and Graham, because they were such good friends,” he observes. “Graham would just support David to the grave. I mean, he just loved him to death. It’s so sad to see that. I don’t even know what it’s about. It’s about, like, Neil Young’s girlfriend? C’mon. That’s petty stuff, man. Get over it.”

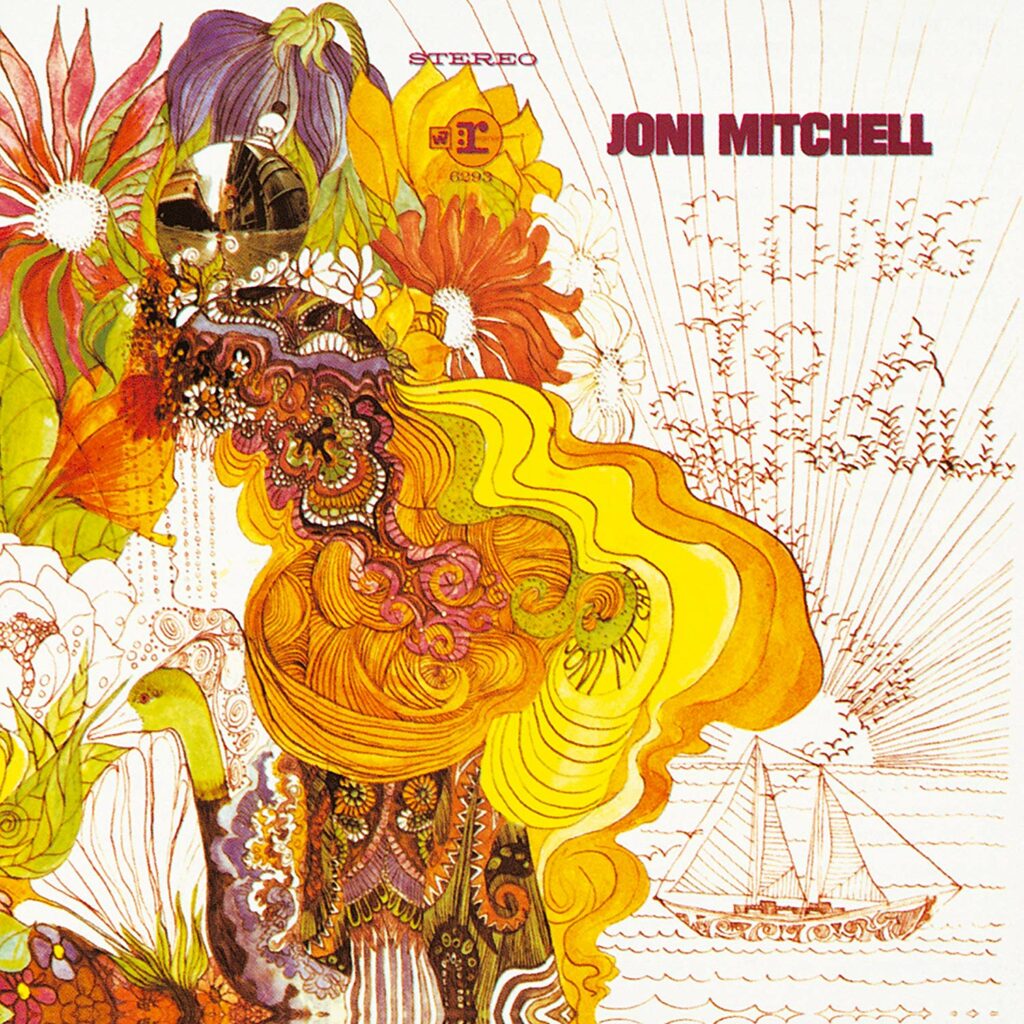

Elsewhere in the bonus features, by the way, is a real interesting observation by Crosby on an important achievement of his just after he left the Byrds. The nearly half-hour film of a Q&A between Crosby, Cameron Crowe (who conducts interviews with Crosby in Remember My Name), and an audience after a screening of Remember My Name is, like most such things, only mildly interesting. But one of the questions/comments is one that I would liked to have put to Crosby. An audience member tells David he’s always loved Crosby’s production of Joni Mitchell’s 1968 debut album (Song to a Seagull aka Joni Mitchell), although both Mitchell and Crosby have almost apologetically denigrated the record’s imperfections.

Back in 1968, Mitchell told Gene Shay of Philadelphia radio station WHAT that “the process that took off the hiss from the album took off a lot of the highs, which is the reason it sounds like it’s under sort of glass…under a bell jar, that’s what Judy [Collins] said. So you really need the words inside the book to follow my diction, which is pretty good, usually.” Part of that problem could be traced back to Crosby’s ingenious miking of piano strings as Joni sang her vocals into a grand piano, which created unforeseen difficulties later in the production process. “I wanted to try and get the overtones that happen from the resonating of the piano and, of course, it recorded at way too low a level,” Crosby told Wally Breese of the JoniMitchell.com Web site in 1997. “If you use those mikes at all you get a hiss, so we had to go in and take those things out.”

In Remember My Name, Crosby doesn’t backtrack that assessment, but accurately feels that the album did capture “her essence.” Personally, I’ve always loved the LP’s hushed ambience, which creates an almost ethereal mystery. I loved it even when I got a fairly beat-up used copy for $3 at a socialist bookstore back in 1982 as a twenty-year-old. I never noticed flaws in the sonic quality, and if I’m much more aware of how Mitchell and Crosby perceive them as such now, they’ve never bothered me. And Crosby’s response to the fan in the audience who loves the album elaborates upon its unique atmosphere in a way I’ve never seen or read him do elsewhere.

“I love that record,” he says. “I think the main thing I did was I didn’t let the rest of the world try to play on that record because they wouldn’t have known how. And because her arrangements at that point were indicated arrangements of an entire band, which is what we folksingers do on the guitar. We kind of approximate the sound of a band. And she was better at it than anybody. Better at it than me, that’s for sure.”