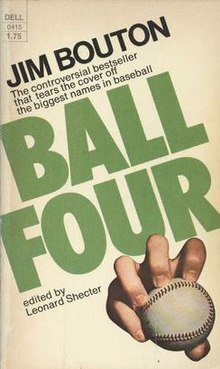

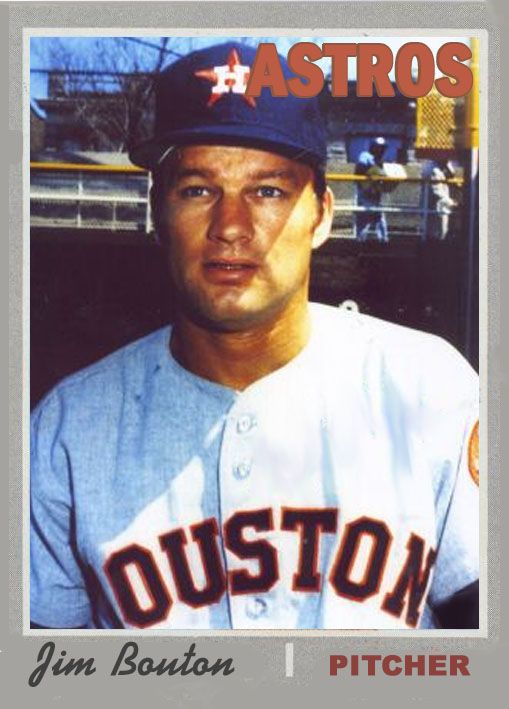

This spring marks the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of Jim Bouton’s Ball Four. As I’ve written before, I think it’s the finest first-person account of playing major league (and, for a bit, minor league) ball over an entire season. It’s more than that: I’d say it’s the best sports book, period. And an important book on its own terms, not just for its documentation of baseball.

Bouton questioned many of the sport’s norms, most famously the reserve clause, but also the general baseball culture that often treated players callously. As a nonconformist in a conformist environment, he also championed the underdog, making many like-minded young readers feel that they too had voices worth hearing.

And—in a point often overlooked by retrospective overviews of Ball Four, even very positive ones—it’s very funny. Some other memoirs have been hailed as worthy cousins to Ball Four, and I’ve tried some (such as Bill Lee’s), but none seem, to use baseball terminology, even in the same league. Maybe part of that well-written wit is down to sportswriter editor Leonard Shecter, whom Bouton never shied away from crediting as his collaborator. I have to think, however, that much of it is down to Bouton just being a naturally funny and insightful storyteller who’s not afraid to shoot sacred cows.

Bouton died last summer, at the age of eighty. If I’d been able to ask him a few questions about Ball Four, here are some that come to mind. Most of them are interrelated, and some might have made him uncomfortable, despite my admiration for the book.

1. From the standpoint of making a story, does he think the season couldn’t have turned out any better?

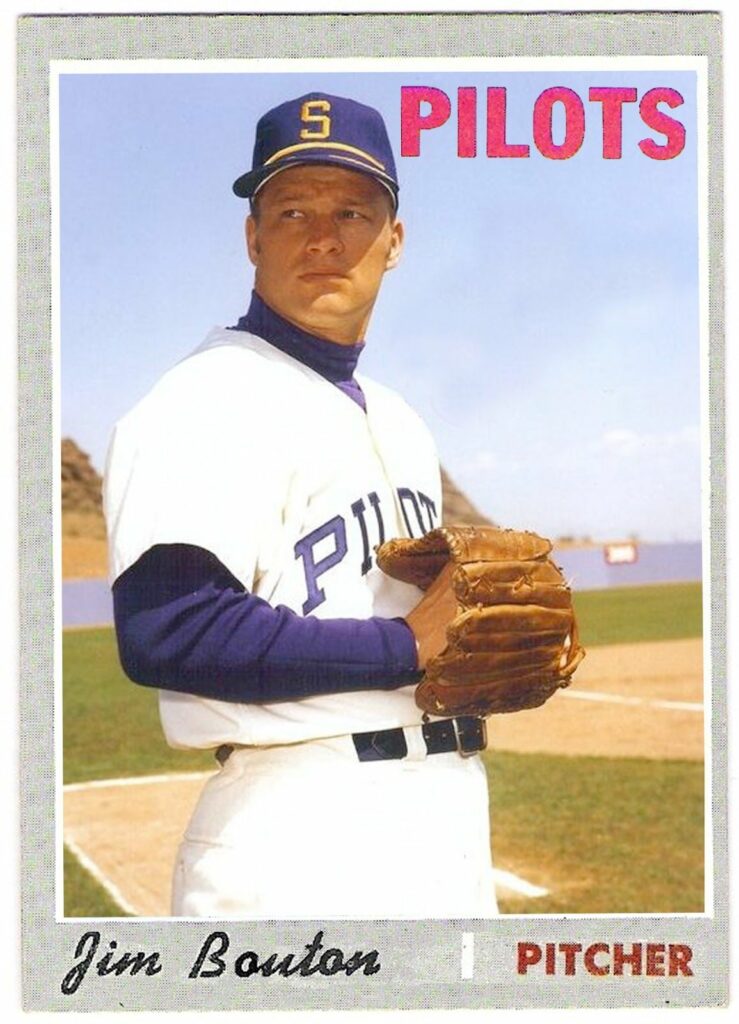

I think it could have hardly turned out any better. You couldn’t plan this, but the three sections vividly illustrated three very different aspects of the ballplayer experience. The one taking up the bulk of the book had him with the first-year expansion team the Seattle Pilots—who would only stay in Seattle one year before moving to Milwaukee. (Just to clarify for any curious readers, the Seattle Mariners, who’ve been in the city since 1977, were not the same franchise.) So you have the sometimes comic drama of a team of rejects from other squads, green rookies, and over-the-hill veterans trying as best they can to survive.

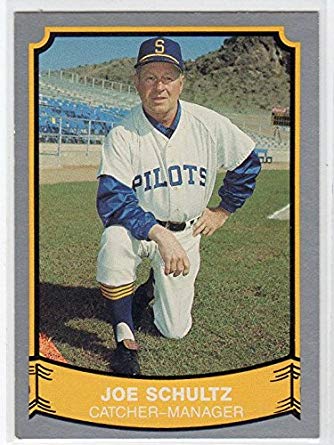

The briefest, but still memorable, section had him sent down to the minors for a few weeks in April, after he’d been in just a couple games. Bouton then reeled off a series of impressive relief stints that got him called back up, even though manager Joe Schultz had told him “Well, if you do good done there, there’s a lot of teams that need pitchers” the night he was demoted. As luck would have it, that brief time in the minors took in a week-long trip to Hawaii, as well as a brief stopover in Vancouver, where Seattle’s Triple-A team was based. That lent a tinge of exoticism to the narrative, but also served as a bold contrast to the much plusher life led by major leaguers.

For the final section, Bouton unexpectedly found himself in a different league and the midst of a pennant race when he was traded to the Houston Astros in late August. Again, a mightier contrast to his time with the Pilots could have hardly been staged, unless he’d been traded to the Miracle Mets, who were on their way to the most improbable World Series victory in history. Alas, though they were two games out of first in the National League’s Western Division on September 10, the Astros lost 16 of their last 22 games, finishing fifth and a dozen games back.

Probably Bouton, and his publisher, would have preferred that the Astros gone on to win the World Series, with Bouton as a hero winning the final game. That would have likely helped sell more books, but it also would have obscured the title’s ultimate more everyman experience. Most major leaguers aren’t World Series heroes (though Bouton was, back in 1964, the second of the two consecutive years he was an ace for the New York Yankees). They’re usually more like Bouton in 1969, bouncing from team to team, from majors to minors, and indeed struggling to hang on to a major league job.

As Bouton noted in his epilogue, in spring 1969, he’d started out even with Jim O’Toole, another former ace trying to make the Pilots. O’Toole didn’t make the club, and indeed never pitched in organized baseball again; by the summer, he was pitching in the semi-pro Kentucky Industrial League. Bouton might have been cut from the Pilots too, in which case there wouldn’t have even been a book. But his journey between three teams could have hardly made for a better, more varied scenario.

2. As he was traded with a little more than a month to go in the season, did he feel more at liberty to write with frankness about his Seattle Pilots teammates, manager, general manager, and coaches?

I don’t remember ever reading or seeing Bouton asked this. If he hadn’t been traded near the end of the year, he would have been returning to the Seattle Pilots (or, as they became, the Milwaukee Brewers) in 1970. Although he wasn’t as personally critical about the team’s personnel as some have reported, there were certainly details many would have preferred to keep private, especially as few of the Pilots knew he was writing a book. (It seems that none were, other than his roommates Gary Bell, Mike Marshall, and Steve Hovley, as well as his brief minor league roommate Bob Lasko.)

There were a few guys in Seattle who didn’t come off well in Ball Four. Worst was bullpen coach Eddie O’Brien, with whom Bouton often clashed over his petty rules about how to do things, Jim nicknaming him “Mr. Small.” Not much better was pitching coach and ex-Giants star Sal Maglie, whom Bouton admired as a fan growing up in the New York area, but with whom he had differences with the Pilots, especially over when and how often to throw his knuckleball.

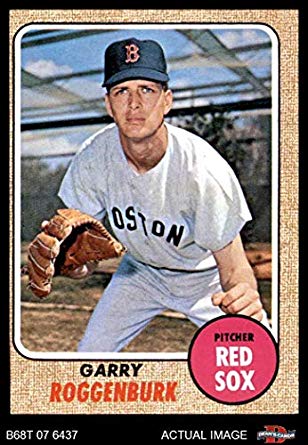

Bouton and outfielder Wayne Comer didn’t get along, Comer sniping “get him the fuck out of here” when Bouton went into an intellectual explanation of a book he was reading, and the pair briefly arguing when Comer said the same thing about a fan coming on to the team bus thanking fellow pitcher Garry Roggenburk for tickets. Although pitcher Fred Talbot isn’t portrayed as badly as some have reported—he and Bouton had some friendly interactions as well as contentious ones—he does come off as something of a redneck, especially when he jumps in front of Bouton to get a cab and calls him a communist.

While Bouton didn’t have anything particularly negative to say about the personality of another former ace, Steve Barber, he came down hard on Barber for lingering on the active roster when he could have gone on the disabled list or rehabbed in the minors. “There was Steve Barber getting his road uniform refitted,” observed Bouton. “I guess he wants to look good while sitting in the diathermy machine. ‘You son of a bitch,’ I said to myself. ‘You’re the guy who won’t go down in order to help out the club. Instead you hang around here, can’t pitch, and now other guys are sent down because of you.’”

They did get along well enough for Bouton to throw knuckleball pitches to him—Jim had a hard time finding people, catchers or otherwise, to catch him due to the knuckleball’s unpredictable movements—in exchange for him catching sore-armed Barber. When Mike Marshall was sent down to the minors after rooming with Bouton for just a few days, Bouton and Barber were assigned to room together, but just switched keys so Bouton could room with his friend Steve Hovley. When the incident’s reported in Ball Four, nothing is said as to whether Bouton’s reluctant to room with Barber.

Even some of the guys Bouton basically likes have their bad points noted. He originally thought of slugger Don Mincher as something of a redneck due to his heavy Southern accent. Yet he was man enough to admit, when Mincher encouraged him to hang in there after being sent down to Vancouver, “I really was wrong about him. He’s a good fellow.” Still, when Mincher and Joe Schultz bail out of a clinic for underprivileged kids in Washington, DC, he reports, “I don’t think Joe would have gone back to Baltimore alone, and I don’t think Mincher would have either. But they gave each other just enough support to do it together. They were less afraid, both of them, of running out than they were of facing this great unknown that involved so many people.”

This is also the one page that puts Schultz in a pretty poor light, in these paragraphs:

“Mike Marshall said he thought he understood what had happened with Joe Schultz and Don Mincher. ‘I could see it coming,’ Marshall said. ‘Joe couldn’t cope with the situation. He wasn’t in charge. He was forced to follow along. It was frustrating to him not to know what the plan was and he’s neither intelligent nor competent enough to be at ease with the unknown. That’s why he surrounds himself with other people, coaches, who are as narrow as he is. He wants to rule out anyone who might bring up new things to cope with. He wants to lay down some simple rules—keep your hat on straight, pull your socks up, make sure everybody has the same-color sweatshirt—and live by them.’

“And it was obviously true. Like on the bus going to Washington, Joe Schultz and I were sitting across the aisle from each other. I handed him the sports section of the paper and when he was through with it I asked him if he wanted to read the rest of the paper. ‘Nah,’ he said. ‘I don’t read that.’ There’s no comfort for Schultz in the front of a newspaper. When he wants comfort he can get it from somebody like Mincher.”

I don’t know whether Schultz read that passage (though he hadn’t read the book at all a couple years later, according to Bouton), but he wasn’t happy about Ball Four. “A year after the book came out I was a sportscaster from New York covering spring training in Florida,” wrote Bouton in his updated edition of Ball Four. “Before a game one day I spotted Joe Schultz, then a Detroit Tiger coach, hitting fungos to some infielders. I hadn’t spoken to him in about two years. Naturally, I had to go over and say hello.

“I half expected him to tell me I was throwing too much out in the bullpen. Instead, he said he didn’t want to talk to me, that he hadn’t read my book, but he’d heard about it. When I tried to tell Joe that he came off as a good guy, Billy Martin, the Tiger manager at the time, who’s a bad guy, came running across the field hollering for me to get the hell out (this was before Martin wrote his tell-all book). Because I’ve grown accustomed to the shape of my nose, I got the hell out.”

Maybe Schultz would have been upset to read him frequently—very frequently—quoted good-naturedly cursing up a storm, as well as some places where he acts goofy, like when he’s smiling after a Pilots loss because Lou Brock (of the Cardinals, where Schultz had coached) has stolen successfully on his first 25 attempts. But Bouton does on the whole treat him well. “There’s a zany quality to Joe Schultz that we all enjoy and that contributes, I believe, to keeping the club loose,” is one of his observations. “It makes for a comfortable ballclub.” Elsewhere he notes, “I’ve heard no complaints about Joe. I think he’s the kind of manager everybody likes.” And when Schultz called him to tell him he’d been traded, Jim “told him I thought he was a helluva man and that I was sorry I couldn’t do more for him.”

Furthermore, in the anthology of pieces about managers Bouton oversaw (I Managed Good, But Boy Did They Play Bad), the pitcher wrote, “I enjoyed pitching for him more than any other manager I ever played for…Under the circumstances I couldn’t have had a better manager that summer than Joe Schultz.” And in his follow-up book to Ball Four, I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally, Bouton quotes Schultz as saying the following about Ball Four: “What the shit. The more I think about it, it’s not so bad.” Adds Bouton after that quote, “Some day there’ll be a movie made of Ball Four. Only Joe Schultz could play Joe Schultz.”

All this speculation might be moot, since between 1969 and 1970 in their transition from the Pilots to the Brewers, the team underwent more personnel changes than almost any I can think of in such a short period of time. Schultz and the whole coaching staff were fired. Talbot was sent to Oakland just a few days after Bouton was traded to Houson; Mincher was traded to Oakland in the off-season; Barber was released, though he’d pitch five more years for other teams; and Comer went 1 for 17 for the Brewers before getting traded in May to the Senators.

There were enough ex-Pilots on Milwaukee, however, to cause some commotion. As Hovley reported in I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally, “The ball club is really in an uproar. Every guy on the club has a copy of the magazine [in which excerpts of Ball Four appeared before the book was published] and the excerpt is the topic of conversation from the time the bus leaves the hotel until the bus returns from the ball park after the game. They’re all looking at the dates in there and trying to figure out how many other dates are going to be in the book and what they might have done on them…[pitcher] Gene Brabender wants to know how you’d like to take a ball in the chest.”

General manager Marvin Milkes’s two-faced penny-pinching ways are slammed in Ball Four, but he didn’t seem to take it personally. According to the Ball Four update, Milkes invited Bouton to lunch a few years later and offered to pay him $50 for Gatorade for which Jim hadn’t been reimbursed. “Of course I didn’t accept, but we had a good laugh about it,” Bouton wrote. “Marvin told me he liked the book because it helped open a few doors for him. He said wherever he goes, people ask him if he’s the Marvin Milkes in Ball Four.” Maybe he found that any publicity was good publicity in his line of work.

3. Did Bouton go easier on the Houston Astros because he knew he’d be back with that team in 1970?

It seems like it. There’s very little in the entries documenting his month or so with the Astros that would cause offense. About the worst incident is one where a fight broke out on the team bus between Jim Ray and Wade Blasingame, after Ray teased him about a woman in Blasingame’s room. Manager Harry Walker’s sometimes bombastic manner is mocked a bit, as are general manager Spec Richardson and (for his curfew bedchecks) coach Mel McGaha. This didn’t stop Bouton from inscribing in the copy of Ball Four he gave Walker, “I have more respect and admiration for you than any manager I’ve ever played for.”

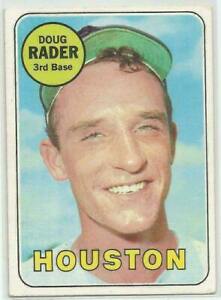

Bouton is very complimentary about the personalities of a number of Astros, including his roommate Norm Miller, Larry Dierker, Doug Rader, and pitching coach Jim Owens. He’d also been very complimentary about some Seattle Pilots, including, besides his roommates, Tommy Davis, Marty Pattin, and (though he didn’t make the club before going on to a long career) Skip Lockwood. He also makes a point of noting how on the Astros, “The blacks go out of their way to join with whites and the whites try extra hard to join in with the blacks…It doesn’t seem forced, and I think it’s worth a lot to the ballclub.”

4. Was Bouton deliberately protective of some marginal players on the Pilots, not or barely mentioning them in the book so it wouldn’t adversely affect their careers?

Again, it seems that might have been the case. Bouton mentions taking utilityman Gordie Lund and pitcher Garry Roggenburk on his neighbor’s boat in Puget Sound with his family. But he barely mentions them elsewhere in the book, other than as part of an interesting incident not long afterward, when Roggenburk unexpectedly quit baseball and Lund (his roommate) drove him to the airport.

The night Bouton was sent down to Vancouver, he makes a point of noting that reserve outfielder Jose Vidal “was the first guy to come over and say he was sorry to see me go,” and that backup catcher Freddie Velazquez was the second. “At that point I felt really close to them,” Bouton wrote, though they’re seldom named elsewhere in the book. He called Diego Segui—not a marginal player, but about the best pitcher on the team—“a good fellow” in passing, but otherwise wrote little about him. Maybe it was simply a matter of not talking much with Latin players who didn’t speak English as their first language.

Reserve outfielder Steve Whitaker played 69 games for the Pilots, and had been a teammate of Bouton’s for the three previous years with the Yankees. The only time he’s mentioned is in the context of the Yankees years, for being invited onto The Match Game (Bouton wasn’t) and a run-in Whitaker had with an umpire. Or maybe this is reading too much into things, and Bouton just didn’t have anything interesting to say about the player.

5. Could Bouton’s personality had something to do with him being traded to the Astros, especially as it happened a few days after he’d argued with some of the Pilots in the bullpen?

After pitching poorly and getting taken out of the game on August 18, Bouton wanted to throw pitches in the bullpen, as he didn’t think he had the right feel of his knuckleball and wanted to work on it. No one showed much enthusiasm for this, including the bullpen catchers, and fellow reliever John Gelnar made fun of Bouton. Jim kind of blew up, stopped throwing, and delivered an angry mini-tirade about their insensitivity, coming down especially hard on Eddie O’Brien, who told him to take a shower. Bouton did promptly apologize after the game to everyone except O’Brien.

“I don’t really think I did myself any good in the bullpen tonight,” admitted Bouton in his diary entry. “I mean what will get around about it is not that I said some tough things, but that I delivered a short speech in front of the bullpen. Nobody delivers short speeches in front of the bullpen.” This seemed to blow over, as a couple days later, “Sitting in the bullpen tonight it seemed as if I’d never given my little bullpen lecture. The guys were coming over to tell me stories and I felt right back in the swing of things.”

Still, Tommy Davis—who was traded to the Houston Astros just a few days after Bouton—told Jim “the talk around the club was that I wasn’t traded just to get two players, but because Marvin Milkes wanted to get me off the ballclub. The rumor did not explain why.” Speculated Bouton, “Gatorade?” (Referring to their dispute over him getting reimbursed for ordering it for the Pilots.) That’s a funny quip, but maybe the bullpen speech did have something to do with it.

6. Was Bouton surprised that some of the players he describes as misfits or flakes went on to careers as respected managers?

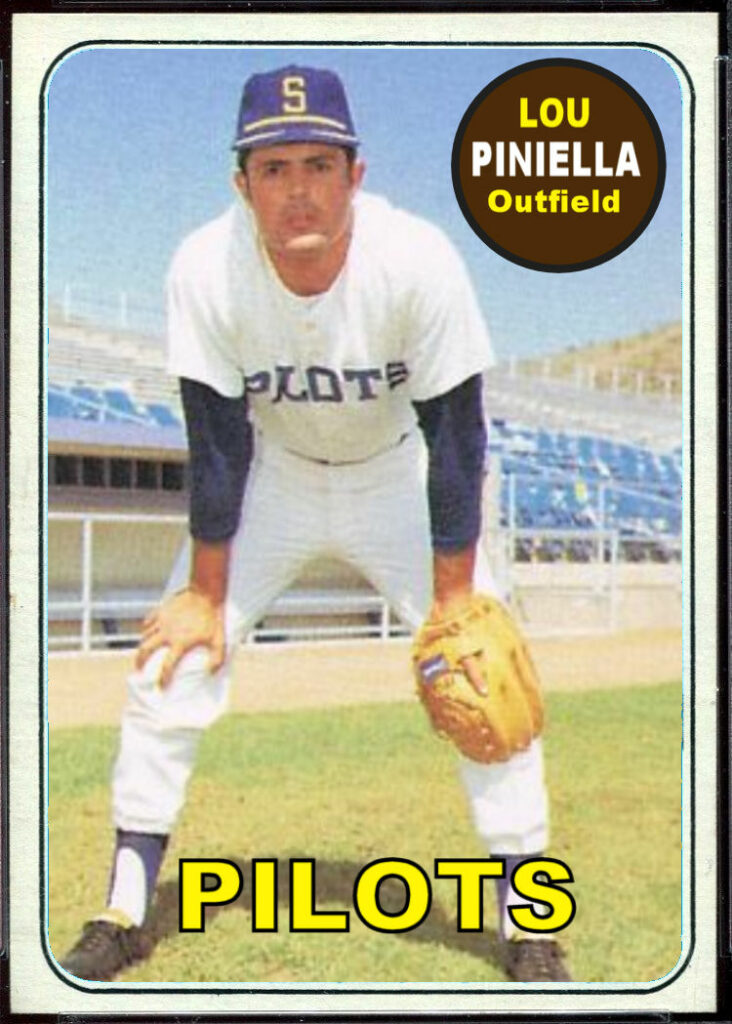

Lou Piniella was with the Pilots in spring training, but traded before the season began. Bouton gives the impression it was because of Lou’s attitude. “Sounds like somebody up there wants to unload Lou Piniella,” he speculated after reporting on a run-in between Piniella and Schultz. And a few days later: “Lou Piniella has the red ass. He doesn’t think he’s been playing enough…He says he knows they don’t want him and that he’s going to quit baseball rather than going back to Triple-A.”

A few days after that: “Piniella is a case. He hits the hell out of the ball. He hit a three-run homer today and he’s got a .400 average, but they’re easing him out. He complains a lot about the coaches and ignores them when he feels like it, and to top it off he’s sensitive as hell to things like Joe Schultz not saying good morning to him. None of this is supposed to count when you judge a ballplayer’s talents. But it does.” When Piniella was traded, “like we all knew Piniella would be canned and it happened today. He was traded to Kansas City for Steve Whitaker and John Gelnar, a pitcher. It was a giveaway. Bound to happen, though. Lou just wasn’t their style.”

It doesn’t sound like a recipe for a longtime player, let alone a manager. But Piniella went on to win the 1969 Rookie of the Year award for Kansas City, and then to a long career as major leaguer that lasted until he was forty years old in 1984, taking in stints as a valuable contributor to World Series titles for the Yankees in 1977 and 1978. Then he managed several teams for periods totaling more than twenty years, landing a World Series title for the Reds in 1991. You don’t get to do that unless you learn to get along with the baseball establishment, or at least find teams where you can do that.

Astros third baseman Doug Rader is described in detail as the team’s prince clown, playing practical jokes and, when the tension of the pennant race got to him, putting his mouth to a shower nozzle so it looked like water was coming out of both his ears. No one disputed he played hard, however, and he’d manage the Rangers and the Angels for a total of about six years in the 1980s and early 1990s. You’d rather have a manager with a sense of humor than a skipper without one—a point Bouton subtly made about Joe Schultz, though Rader’s sense of humor was likely more sophisticated. It’s too bad Rader didn’t get more of a chance to manage in the big leagues.

Larry Dierker, the ace of the Astros (a highlight of Bouton’s stint with the team was saving his twentieth win in September), is portrayed in the book as a loose, funny, freewheeling guy, though again a very serious competitor on the ball field. Among the highlights of the Astros section is an account of how Dierker sang the Beatles’ “Rocky Raccoon” to himself on the bench between innings while he was working on a shutout. He and Bouton also agreed they much preferred the Beatles to the country music a lot of other ballplayers did; you can read more about Ball Four’s musical references in this prior blogpost.

Dierker went on to a long career as an Astros broadcaster before unexpectedly being hired to manage the team in 1997, despite no professional managerial experience. This had all the marks of an impulsive move in the face of conventional baseball wisdom that would blow up in everyone’s faces, but actually it worked out pretty well. The Astros finished first in their division four of the five years Dierker was at the helm. His firing had more to do with their poor postseason record (2-12, never advancing beyond the first round) than his in-season performance. Obviously he took his responsibilities as managers very seriously. He also wrote a book that focused on them, This Ain’t Brain Surgery, though it was a more straightforward, conventional baseball volume than Ball Four. Again it’s unfortunate he didn’t get the opportunity to manage for more years.

The most famous player Bouton played with in 1969 was Joe Morgan, then second baseman for the Astros, though it was his superstar years with the Reds in the 1970s that would put him in the Hall of Fame. Bouton doesn’t have much to say about Morgan in Ball Four, though he compliments his skills turning double plays. It’s hard to tell how negatively Morgan felt about the book from a quote attributed to him on Mark Armour’s article about Ball Four on the Society for American Baseball Research site: “I always thought he was a teammate, not an author. I told him some things I would never tell a sportswriter”—though such things, whether they were controversial or not, aren’t in the book.

Bouton didn’t play with Nolan Ryan, who was just starting his career with the Mets in the late 1960s, and became one of the most famous pitchers from his era. Ryan’s image is pretty conservative, in part because of his long friendship with the Bush family, George W. Bush being a part-owner of the Rangers while Ryan pitched there. But there’s little-known evidence that he read and enjoyed Ball Four. I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally reprints a letter from Ryan’s wife Ruth, who wrote:

“I want to congratulate you on your success with Ball Four. I bought it in Houston in July, and both Nolan and I enjoyed it very much. We have often discussed the pretentiousness, the loneliness, and the frustrations which accompany baseball; and your honesty and subtle sense of humor captured that aspect so well.”

7. How does he feel about the books he did after Ball Four in the early 1970s: I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally and I Managed Good, But Boy Did They Play Bad?

Ball Four was going to be an impossible act to follow. Even if Bouton had stayed in the majors (he quit baseball in summer 1970), no team would have welcomed him doing another diary book of a season. It would have been impossible to recreate the circumstances that helped Ball Four’s narrative in any case. But he did come out with a follow-up, I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally (also in collaboration with Shecter), in 1971, just a year after Ball Four.

I don’t think I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally sold that well. It did get into a paperback edition, but you don’t see many copies around. It’s pretty good, though, if not as in-depth or electrifying as Ball Four. It focuses on the reaction and fallout from Ball Four, and also includes quite a few stories from his last season with the Astros in 1970, though these aren’t delivered in Ball Four’s diary form. There are some good stories from other points in his career, though the chapters on his transition to TV broadcasting aren’t as interesting.

There’s also an interesting, if more specialized, chapter on the ins and outs of the book deal for Ball Four. Bouton was subject to many runarounds from his publisher, whether not getting as much money as he thought he would from the terms of his contract; staff turnover at the publisher that left him dealing with people who hadn’t put him under contract and didn’t particularly want to put out the book; incompetent promotion and book tour support; manipulation of the release date that forced him and Shecter to settle for worse terms; and, worst of all, insensitive editing of the controversial material, which he and Shecter had to fight hard to restore.

“Every single passage which told some truth, every passage that may possibly have been considered tough, or funny or sexy, was neatly excised,” complained Bouton. “Example: The section in which I talked about the Yankees staying out late and partying whenever they played in Los Angeles was crossed out and this note was attached to the margin: ‘Is this possible?’ Nah, I made it up.

“An incredible job was done on the manuscript. If we had allowed these changes to stand, Ball Four would never have been heard of. We could have changed the title to Peter Rabbit Goes to the Ballgame. We wore out two erasers just restoring what the…copyreader had taken out.”

(As an aside, Ball Four itself was edited down from many tapes Bouton made during 1969. I’d like to read the unedited transcripts of those, in case they survive, though usually what doesn’t make a book isn’t nearly as interesting as what does. Fortunately, his personal papers and related materials are now preserved at the Library of Congress. According to a blog on the Library of Congress site, “the glory of the collection is the hastily scribbled notes, the audiotape transcripts, and the drafts of Ball Four.”)

Bouton relays all of these injustices as if he and Shecter were victims of particularly unfortunate staff at their publishers. As a published author myself, I can tell you that half a century later, very similar ones are not uncommon. Probably they weren’t uncommon back in 1970. But he felt like he was getting screwed, because it wasn’t something he went through in his chief profession. Maybe he got a better deal with I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally, although unlike Ball Four, it wasn’t a bestseller. Follow-up books often get a better deal, in part because it’s reasoned that based on the success of the author’s prior book, enough people will buy it to turn a profit no matter what kind of book it is.

Although the credit for 1973’s I Managed Good, But Boy Did They Play Bad reads “written and edited by Jim Bouton with Neil Offen,” in fact most of it’s not written or edited by Bouton (or Offen). It’s an anthology of pieces about managers from the early twentieth century to the 1960s, most of them previously published. Bouton did write a few chapters, including an overall introduction and the sections on the Yankees mid-‘60s skippers (Ralph Houk, Yogi Berra, and Johnny Keane), Dick Williams, and Joe Schultz. Those chapters are pretty good and funny, as are some briefer Bouton-penned comments on some of the managers for which he didn’t write the essays. The other essays are okay, but there’s the sense his name was being used to sell a book that wasn’t really his, or that he’d compiled rather than (for the most part) written.

8. What did he think of his first wife’s book?

In 1983, Bouton’s first wife, Bobbie, wrote the memoir Home Games with Mike Marshall’s ex-wife Nancy. The book’s not so great, in part because of a contrived structure that takes the form of imaginary letters they might have written to each other about their lives and husbands. However, it doesn’t portray Bouton in a very positive light, detailing some of his imperfections as a husband and father. Both he and Marshall come off as kind of egotistical guys—not that it’s so common among star athletes.

Those unsympathetic to Bouton’s undercover reporting in Ball Four might say he was getting a taste of his own medicine. The pitcher had this to say about the book to George Vecsey of the New York Times in 1983:

“We all have the right to write about our lives, and she does, too. If the book is insightful, if it helps people, I may be applauding it.

“I’m sure most of the things she says are true. I smoked grass, I ran around, I found excuses to stay on the road. It got so bad that I smoked grass to numb myself. It took me a year to where my brain worked again. I no longer think of grass as harmless. We were in the death throes of a marriage. She should ask herself how did she not see these things.” According to the story, he had not yet read the book.

Added Bouton in the article, “A lot of guys have been faithful to their wives in baseball. It didn’t happen with me, but I don’t think you can blame baseball. I don’t think I became more egotistical at 38. I was egotistical in the third grade.”