Is the well running dry for reissues of the music I specialize in—twentieth century rock, particularly though not exclusively from the 1960s? No, as the length of this list demonstrates. The kind of reissues that are being generated, however, is getting narrower, now that so many albums from the era (even the best rare ones) have been on CD, and so many singles are available on compilations, best-of or otherwise.

So many of the reissues of most interest are expanded versions of albums—sometimes albums that have already had one or more previous “expanded” or “deluxe” reissues, loading on more outtakes, demos, home tapes, and rarities. By this time it’s rare such boxes are mostly or entirely comprised of actual previously unreleased material by a significant artist, as Joni Mitchell’s first two Archives volumes have been over the past couple years. There are also quite a few boxes by artists you wouldn’t have expected to ever get half-dozen-or-more-CDs packages, like the Beau Brummels and the Electric Prunes, even if such boxes usually don’t offer much fans of the acts don’t already have. And there are super-specialized genre anthologies that have some rarities, but will inevitably overlap to some degree with existing collections of anyone who’s interested in such material in the first place.

Is all of this something to mourn, if you want to constantly discover “new” old music? Perhaps. It could also be something to celebrate. Forty or so years ago, it was impossible to find much of this stuff, and the existence of much of the unreleased material wasn’t even known in many cases. Now you can easily get it, if you have the budget. At this point, in my view, most of the really good obscure LPs have been reissued, and while others continue to get unearthed, they get less and less interesting the deeper you have to dig. That’s not a viewpoint held by every collector, and in fact it will probably make some angry, but that’s my experience.

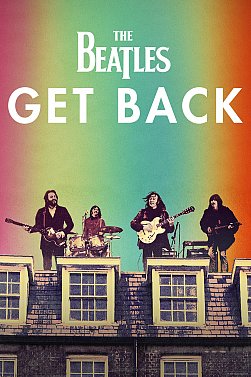

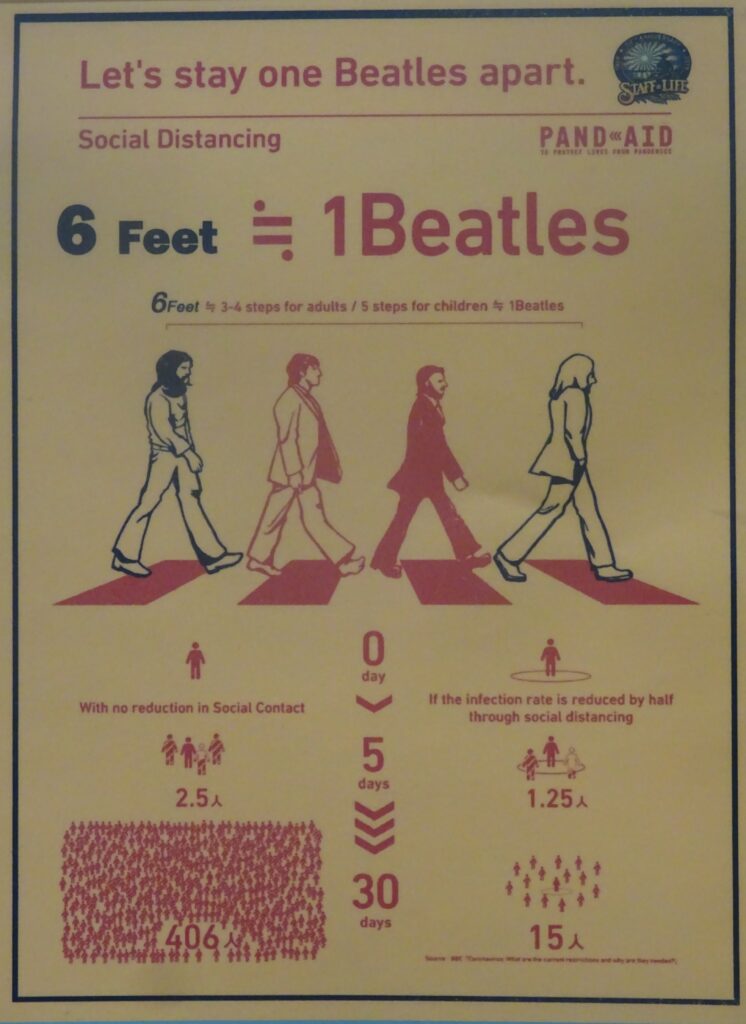

My 2021 lists have been Beatles-heavy, which might disappoint some champions of the obscure. But there’s a reason they’re Beatles-heavy. They were the best rock group, and although some of the reissues/films/books associated with them are imperfect, interesting material pertaining to their legacy continues to be unearthed. And you can hear them and still find time to hear acts that never got anywhere near their attention, from the Misunderstood to Tintern Abbey and Latin soul boogalooers on Fania Records.

1. George Harrison, All Things Must Pass 50th Anniversary Super Deluxe Edition (Capitol/UMe). The 50thanniversary had to wait until the actual 51st anniversary in this case, perhaps owing to the pandemic. No matter—this five-CD box has three CDs of extra and mostly unissued material (the three original LPs are fit onto the first two CDs). Two of those extra CDs were demos recorded on just two days, May 26 and May 27 of 1970. The final disc has outtakes from the proper album sessions, most of them alternate versions of songs that made the record, though five (some of them obvious toss-offs not seriously intended for final consideration) are of songs that didn’t.

If how I decide how to rank such super deluxe boxes matters to anyone, the inclusion of one batch or CD of particularly valuable unreleased material can act as a tiebreaker of sorts. That was the case with another recent box in which George Harrison was involved, the super deluxe edition of The White Album, whose May 1968 Esher demos constitute some of the best previously unavailable Beatles material of all. The same can be said of disc four from this package, which has the May 27 demos.

Harrison was for the most part playing alone on these with only his vocal and light guitar accompaniment, and while they’ve long been bootlegged, it’s a superb grouping of fifteen tracks that are much like hearing George unplugged just after the Beatles split. Among them are early versions of All Things Must Pass songs like “Beware of Darkness,” “Art of Dying,” “Let It Down,” and “Hear Me Lord” that have a lovely intimate feel notably different from the brilliant elaborately produced ones on the LP. Of even more note, more than half of them didn’t make All Things Must Pass, and while they’re usually slighter than the tunes that made the cut, they’re nice and well worth hearing. “Nowhere to Go,” co-written with Bob Dylan, is an especially noteworthy treasure that might have some coy references to the end of the Beatles. The rest are good enough, usually in a folky and even sometimes country-ish way, that I’d contend they make a serious argument that the third disc of the original All Things Must Pass should have been given over to actual songs rather than substandard jams. Not everyone feels this way, but certainly he had some good extras that could have filled out a triple LP sans jams.

On its own, the May 27 demos would have made a good standalone release. Fans will, however, appreciate the two other discs of extras, though they’re usually not on the same level. The May 26 demos, recorded with longtime friends Klaus Voormann on bass and Ringo Starr on drums, are largely sketches for compositions that would blossom into far more effective recordings with Harrison and Phil Spector’s production. Still, it’s interesting to hear George work out the tunes with a more basic approach, and sometimes these are worthy variations in their own right. “Awaiting on You All” (one of three songs on disc three previously released on the skimpy Early Takes Vol. 1) is a gritty, funky, earthy take on the tune, with some growling fuzzy guitar; the same can be said of “I Dig Love.” “I’d Have You Anytime” is more minimal than the LP version, with confident and heartfelt vocals. There are also some songs that didn’t make All Things Must Pass, and while “Going Down to Golders Green” is a throwaway, “I Live for You” has a nice countrified Dylan air, and “Dehra Dun” and “Om Hare Om” a more Indian flavor than most of the eventual album. He also hadn’t abandoned “Sour Milk Sea,” part of the Beatles’ Esher demos before it was given to Jackie Lomax; this is a more straightforward, somewhat more rocking version than the Esher demo, though it’s still not much of a song.

The alternate versions and outtakes from the album sessions mostly demonstrate how the correct, superior takes and arrangement were chosen for the final LP. That’s not a criticism of Harrison; that’s true of the extras on most super deluxe boxes, like the ones of John Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band and The Who Sell Out, to cite a couple more entries on this list. They also show that George’s singing could be kind of thin and strained, and thrived much better in the oft-elaborate arrangements that were among the most distinguishing trademarks of All Things Must Pass.

As with the demos, some variants are more ear-catching than others, like a lower-key, almost dirgey “Art of Dying” and a “Hear Me Lord” with a long, repetitious tag that extends the length to almost ten minutes. A few jams (including a previously uncirculating, and rather straight-facedly performed, “Wedding Bells (Are Breaking Up That Old Gang of Mine”) are superfluous. But the closing, bluesy “Woman Don’t You Cry for Me”—better and about twice as long as the alternate previously surfacing on Early Takes Vol. 1—has excellent slide guitar, and certainly would have been a worthy inclusion on All Things Must Pass had the third original disc been songs instead of jams.

It wasn’t, of course, though you can now experience it that way by sequencing bonus songs according to your preference. And for all the volume this box offers, there might be more, since the liner notes (which finally straighten out what tracks were recorded when) refer to a few recordings not included here, like “an undated personal cassette recorded by George during a visit with brother Pete & sister-in-law Pauline Harrison from late 1969.” Others have made the unofficial rounds, like more than a dozen additional takes of “Apple Scruffs.” So maybe a hundredth anniversary edition will deepen our look at this era even more, though many of us will be gone by then.

A note about the various editions of this box. I have the five-CD/one Blu-ray/no vinyl edition, which has all of the music, and sells for the expensive price of $150 or so. The “uber” deluxe edition, which has five CDs, a Blu-Ray, and eight LPs—no additional music, just an additional format—sells, through the store on Harrison’s site, for $999.98. That’s not a typo—$1000, really. It does have various extras, most of which are in the “can live without” category for me, including replicas of the gnomes on the cover.

However, the liner notes—which, fortunately, I could read in an electronic file, sent to me because I wrote a story on All Things Must Pass—are considerably more extensive, with considerably more day-to-day details on the recording of the tracks. The “scrapbook” that does come with the five-CD edition, which I haven’t been able to read, is an expanded 96-page version. Sure I’d like to read that, but not enough to pay four figures for the box. The jabs at this box getting targeted for those who, to quote the title of Harrison’s next album after All Things Must Pass, are “living in the material world” are going to be inevitable. (My lengthy, nearly 10,000-word cover story on All Things Must Pass, covering the bonus tracks as well as the original LP, is in the September 2021 edition of the UK monthly magazine Record Collector.)

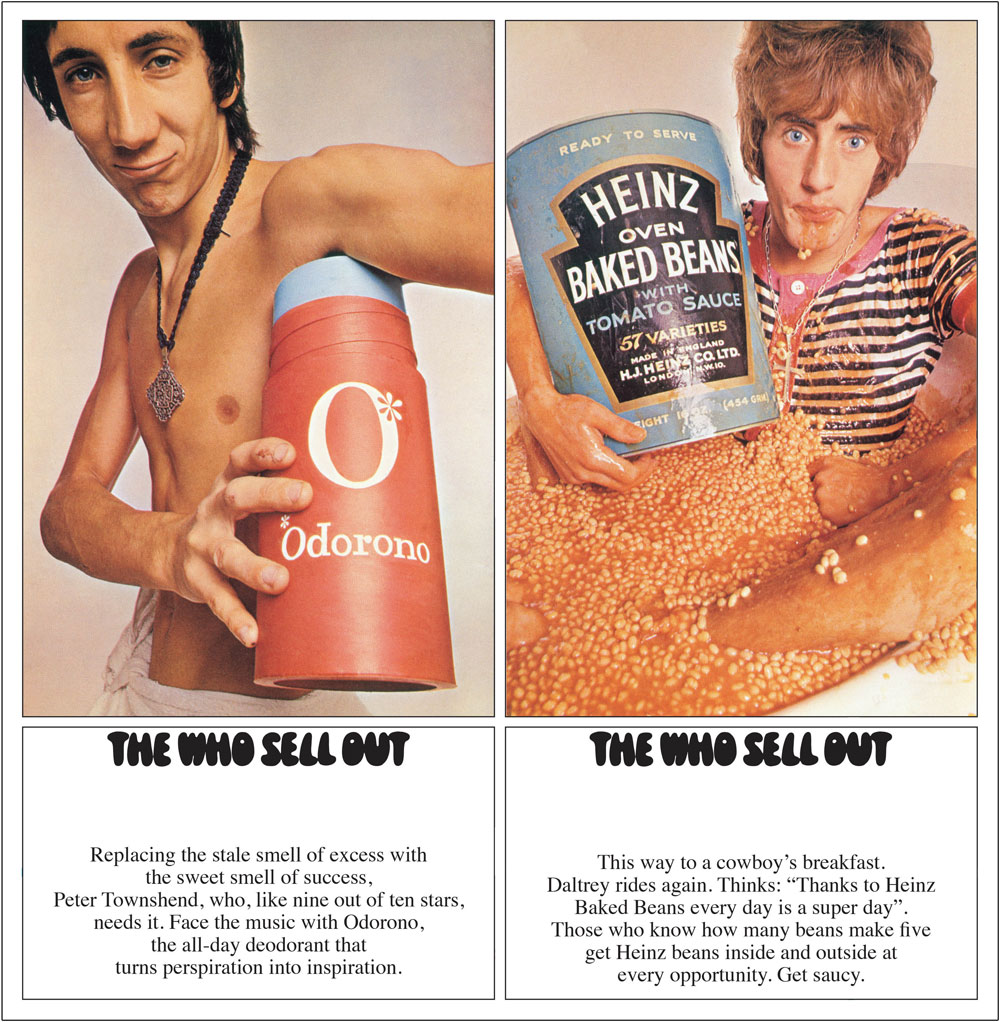

2. The Who, The Who Sell Out Super Deluxe Edition (Polydor/Universal). Although The Who Sell Out wasn’t the Who’s most popular album, it was their most lovable one. The gloriously effervescent power pop, with touches of hard rock, psychedelia, and introspective tenderness, was dotted with pirate radio jingles and fake commercials, simulating an actual offshore UK broadcast. For all its near-perfection (save the inexplicable disappearance of the jingles and commercials partway through side two), there were a lot of unused outtakes, alternative versions, and demos associated with the project.

This five-CD super deluxe edition has almost all of the ones known to exist. True, the best of these have already appeared on other releases, including previous single- and double-CD expanded reissues of The Who Sell Out. It’s still cool to have all of them on an exquisitely designed and, yes, expensive package. Even if, as is often the nature of these things, many of the previously unreleased extras are rather superfluous alternate versions.

Of the 46 unreleased tracks (actually less than half of the box’s total of 112), the most interesting are the fourteen previously unissued Pete Townshend demos that fill up all of disc five. Like the Who-era demos that have been on his Scoop collections, these are naturally sparser than band versions. There’s a slightly spooky homemade ambience and vocals that, while lacking Roger Daltrey’s powerful authority, have an inviting intimate feel. The biggest finds are a couple arrangements that differ notably from the final product.

“Sunrise” (here titled “Thinking of You All the While”) has an almost entirely different melody, and while it’s still one of his most gentle songs from the era, it’s actually more fully arranged than the solo acoustic version on the LP. The lyrics are different and more conventional too, though in every respect, the album redo is more haunting and effective. One of the two demos of “Relax” is piano-driven rather than guitar-oriented, though otherwise similar in construction.

Also here are a couple songs unavailable in other versions. “Inside Outside” is a strange surf-inflected slice of embryonic power pop with obvious debts to “Surfin’ USA.” “Kids? Do You Want Kids?” is a somewhat awkward unused anti-smoking jingle a la, but not as good as, “Little Billy” (an outtake that’s elsewhere on the box). There are also demos of much more familiar songs like “Pictures of Lily” and “Mary Anne with the Shaky Hand,” and the forceful one of “I Can See for Miles” is decisively the best of the lot, complete with multi-tracked harmonies.

Surprises among the previously unreleased full-band outtakes are few. “Relax” is revealed to have started as a far more, well, relaxed piano-grounded song with Townshend on lead vocals the whole way through, and a much less impressive, less melodic bridge. “Odorono” had an unnecessary reprise of the chorus at the end. A brief pass at “Shakin’ All Over” lacks vocals; so, unfortunately, does the hitherto unknown John Entwistle composition “Facts of Life,” though it doesn’t sound like much of a tune. Otherwise the alternates are expectedly rougher and less developed than the completed tracks, though usually not too dissimilar. That doesn’t mean they’re not worth hearing if you’re interested in Who history—just that you’re not likely to revisit them much after you’ve digested their significance as works-in-progress.

Although this box is titled as a deluxe edition of The Who Sell Out, actually it’s more like a summary of what they were doing as a whole between Happy Jack and Tommy. Among the many other extras are non-LP A-sides and B-sides from the era, including the hits “Pictures of Lily” and “Magic Bus”; the singles of “Dogs” and “The Last Time” that didn’t come out in the US; and worthy flip sides like “Doctor, Doctor” and “Under My Thumb.” There are also outtakes from the period bridging The Who Sell Out and Tommy that have been heard on archival releases going back to Odds and Sods, like “Faith in Something Bigger,” “Little Billy,” “Melancholia,” and an early version of “Summertime Blues.” And there are pretty good Who Sell Out outtakes that have been on much slimmer previous expanded CD editions (and on bootlegs for many years before that), like “Glow Girl,” “Jaguar,” the monstrous instrumental “Hall of the Mountain King,” and Keith Moon’s “Girl’s Eyes.”

Be assured, lest it be swamped by the material that didn’t actually make the album, that this box also presents the original album in both mono and stereo versions. The only really striking difference is in “Our Love Was, Is,” which has whimsical slide guitar in the mono solo, as opposed to the superior and more familiar harder-rocking one in stereo. Also here are some mono mixes of non-LP 45s, and the long version of “Magic Bus” that surfaced on Meaty, Beaty, Big and Bouncy is presented in mono too.

As big as this box is, it doesn’t quite cover everything in circulation of note. The absence of a long-booted eight-and-a-half-minute Townshend demo of “Rael,” which includes some lyrical and musical ideas not in the Who Sell Out version, is a significant loss. Less notably, though there are rare actual radio commercials and jingles the Who produced in this era, these don’t include Townshend’s infamous public service announcement for the US Air Force. At least it has rare promo spots for Sunn equipment. “We use Sunn equipment and we find it pretty hard to break,” chirps Townshend in one.

The 82-page bound-in LP-size mini-book has plenty of cool photos and ad repros. There’s also extensive track-by-track annotation by Who expert Andy Neill and short essays by Townshend, recording engineer Chris Huston, and even Arnold Schwartzman (who arranged for the two Coke jingles included in the box), as well as a history of how the record’s exceptionally memorable cover came together. An LP-sized schwag bag has a couple seven-inch vinyl singles with mono mixes of “I Can See for Miles” and “Magic Bus” with a couple period B-sides, along with an assortment of memorabilia facsimiles, highlighted by the poster that came with the original album. It’s a pricey package, yes, but good value for money in the end. (This review originally appeared in the summer 2021 issue of Ugly Things magazine.)

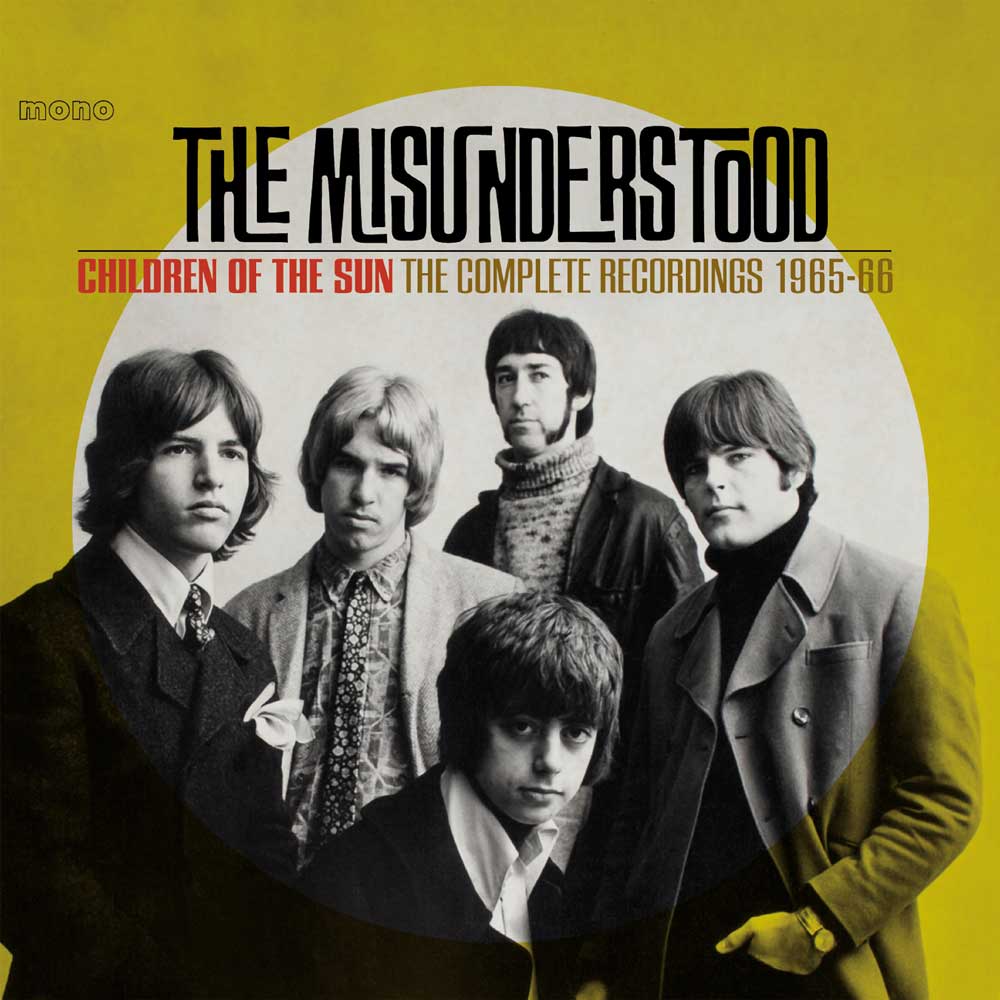

3. The Misunderstood, Children of the Sun: The Complete Recordings 1965-66 (Grapefruit) The Misunderstood’s status as one of the very best rock bands of the 1960s not to make it big is not so much misunderstood as understood. Even if that reputation rests largely on the mere half dozen tracks their best lineup managed to record in London in late 1966, that output remains stunning. Glenn Ross Campbell’s supersonic steel guitar, the mystical lyrics of singer Rick Brown, and the inventive assortment of tones conjured by his songwriting partner, guitarist Tony Hill—all paced some of the greatest psychedelia, almost like a new zenith the Yardbirds never reached after Jeff Beck left.

The tragedy of the Misunderstood was that this lineup imploded right after they reached that zenith. Redemption, sort of, has come in their posthumous acclaim, not least in the mammoth multi-part story told over the course of several issues of Ugly Things. More redemption’s arrived with this two-CD, 33-track compilation. It expands their legacy to a length that seemed unimaginable when the first Misunderstood compilation, 1982’s Before the Dream Faded, offered a mere 13 cuts.

Only one of the items is previously unreleased, and that’s a different version of “Children of the Sun” that principally varies from the single in its slightly different vocals. Still, it’s good to have all of their core discography in one place, scattered as it’s been over Before the Dream Faded, The Lost Acetates, and an out=of-the-way EP and compilation. It’s true the late-‘60s Misunderstood cuts on which only Campbell remained aren’t here, but that’s not such a big deal as most fans (and I’m among them) regard those as much inferior to their mid-‘60s work.

The six late-’66 recordings by the Brown-Hill lineup from Before the Dream Faded (just two of which came out before Brown was forced out of the group by the US military) start things off. These have been remastered by Alec Palao, as he states in the booklet, “from the best tape sources available, including period mono mixes that have not been used until now.” It’s like hearing half a great album, nearly or on par with the likes of Pink Floyd’s The Piper At the Gates of Dawn, that’s somehow missing side two. Maybe no group besides the Yardbirds were as good as blending mind-bending guitar sounds, soul-searching lyrics, haunting melodies, and Indian influences into early psychedelia, though Campbell’s guitar in particular gave them a dimension found in no other band.

The alternate acetate mixes of four of the songs here (two of “Children of the Sun”), it should be cautioned, aren’t that different. Different tape delay echo is at play; “My Mind” has a weirdly different (and not as impressive) vocal, and fades out (unnecessarily) early; and both acetate versions of “Children of the Sun” are missing some vocals on the chorus, to their detriment. None of these alternates are as good as the familiar versions, but they’re still interesting illustrations of how much attention to detail went into perfecting the best ones.

Wisely, the most artistically advanced of their recordings are grouped together on disc one. It’s filled out by two versions of “I’m Not Talking,” which are both impressive in different ways. The one done in London, right before Greg Treadway was replaced by Hill, has a more pronounced raga feel and overall more confidently adventurous vibe. The other, done earlier in Riverside before their move to the UK, has a much longer and in some ways wilder distortion-ridden break. The Yardbirds’ classic arrangement, and not Mose Allison’s original recording, is the obvious model, but the Misunderstood reinterpret it with highly original flamboyance. Also on the first CD are both sides of their rare pre-UK 1966 Blues Sound single, which offer a good British R&B-type take on Howlin’ Wolf’s “Who’s Been Talking” and a less exciting slow blues with Jimmy Reed’s “You Don’t Have to Go.”

Disc two, which might be regarded as a survey of their garage roots, focuses on their earlier, less sophisticated/experimental phase, sometimes with original guitarist George Phelps. Their earliest sides, from the 1965 Phelps lineup, are moody, bluesy garage efforts that can sometimes sound like a rawer Animals, and sometimes like a rawer Del Shannon—sometimes in the same tune. The lyrics are rudimentary in the extreme, but they’re fairly catchy numbers, even if some abrupt tempo shifts are the only hints at the much wilder sounds they’d get into within a year. While some of the straight blues covers are so-so, “Shake Your Moneymaker” is exciting, though they’d soon (like their heroes the Yardbirds before them) move beyond blues classics to writing highly original material.

The early-’66 take on “I Unseen,” from their last session with Phelps, is a highlight of disc two, yet also illustrates just how quickly and far they’d travel over the course of that year. With Phelps, it’s satisfying raw folk-rock, with a hint of raga in the recurring acoustic guitar riff and Gregorian-type backing vocals. With Hill in London, the arrangement’s actually not much different. But Campbell’s steel, and the group’s exponentially greater tightness and tension, take it to a far higher plane. You could say much the same thing with an overall comparison of CD one to CD two – it’s astonishing how much the band changed and improved in such a short time, though you could say that of many groups in the mid-‘60s.

The packaging of this compilation does not disappoint. The 32-page booklet features plenty of period graphics and a lengthy essay by top Misunderstood authority Mike Stax, though his aforementioned epic multi-issue Ugly Things piece (spread across issues 20-23) on the band is recommended for yet more depth. Noise reduction and fresh transfers have improved the listenability of some of the garage-era recordings on disc two, although unfortunately the sources used for some tracks on previous reissues seem to have been lost. Unless there’s yet another miraculous discovery of previously unknown recordings from this era, it’s the last-word anthology of an incredible band that no doubt would have scaled yet more peaks had they remained together. (This review originally appeared in the spring 2021 issue of Ugly Things magazine.)

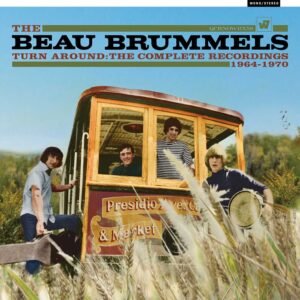

4. The Beau Brummels, Turn Around: The Complete Recordings 1964-1970 (Now Sounds). For a group that’s still sometimes unfairly dismissed as a one-hit or two-hit wonder, the Beau Brummels sure recorded a mountain of material. This eight-CD box has 228 tracks, and while a good number of them are alternate versions, it’s still a testimony to their prolific output, and the incredible wealth of original compositions generated by guitarist Ron Elliott. While only 24 of these cuts were previously unreleased, many of the rest have been scattered over a tangle of reissues dating back about forty years. Compiler Alec Palao was involved in some of those collections, and he’s the man for the job here, also writing the bountifully illustrated and detailed 88-page booklet.

While much of this wasn’t available on LP or at all in the 1960s, the core of the box presents their five 1965-1968 albums, each embellished by lots of demos, outtakes, and alternates. These trace their evolution from the first really good British Invasion-inspired band in the US through first-class folk-rock, their maturation into the more serious psychedelic era with 1967’s Triangle, and then the early country-rock of 1968’s Bradley’s Barn.

Then there’s a whole CD of April 1965 demos; a CD almost wholly devoted to 1965-67 demos and home recordings (usually done separately, and occasionally together) by the band’s principal figures, Elliott and singer Sal Valentino; and a disc featuring the A-sides and B-sides of all their singles, complete with original mono versions, 45 edits, and rare Valentino solo efforts. Fine songs—dozens, in fact—other than their big “Laugh, Laugh” and “Just a Little” hits abound throughout the set, often bolstering their credentials as underrated folk-rock pioneers.

Like almost all significant artists, the Beau Brummels used good judgment when determining what to release (the Beau Brummels ’66 album being a notable exception). Yes, the abundance of extras, and abundance of excess Elliott compositions in particular, are nearly always pleasant, and sometimes better than that. Still, some of the material that didn’t make the cut was, if seldom pure throwaway, often less substantial than their initial two albums for Autumn Records in 1965.

Much of the best of the surplus was assembled back in 1982 for Rhino’s From the Vault, with songs like “Love Is Just a Game,” “Gentle Wand’rin’ Ways,” “She Sends Me,” “I Grow Old,” and “Can’t Be So” rivaling the better folk-rock from their second album, Volume Two. There are some highlights that didn’t emerge until later, like the bossa nova-flavored “Hey Love” and Sal Valentino’s haunting composition “This Is Love.” And it’s fun to hear them bash it out like the early Kinks did on album filler for “That’s All That Matters,” with a rare lead vocal from drummer John Petersen.

Beau Brummels ’66, their inexplicable all-covers album of that year, still sounds like a mistake to me. But the picture of what the band were truly up to that year is corrected by the fifteen bonus tracks on that disc, largely devoted to originals. These range from respectable to quite good, whether dignified folk-rock (“She Reigns”) or Valentino compositions that show him developing into a promising writer, if not in Elliott’s league (“On the Road Again”). And if you missed out on Elliott’s solo demo of “Candlestickmaker” (revived for his 1969 solo album), which was previously only on the various-artists archival compilation Transparent Days, that’s here too.

While Triangle wasn’t exactly psychedelic in the Fillmore/Avalon sense, it had a mystical tinge and more elaborate production distinguishing it from their early British Invasion/folk-rock hybrids. The extras on that disc aren’t quite as illuminating as on some of the others, but do include “Galadriel,” which is up to the standards of what made the LP (and conceptually would have fit in well with its Lord of the Rings tinge). I’m not as big a fan of the rather sedate country-rock Bradley’s Barn as some other listeners are, but this too is bolstered by some outtakes that vary the mood. Those include a couple Valentino solo covers of Johnny Cash songs, as well as a version of “Long Black Veil.”

The April 1965 demo session features some fine tracks first heard on From the Vaults, as well as more testimony to Elliott’s rather astonishingly fertile flow of new songs at the time, though some of these are rather undistinguished or similar-sounding. A few numbers from the pen of early member Dec Mulligan demonstrate he wasn’t going to rival Elliott (or for that matter Valentino) as a composer, though they’re acceptable British Invasion-style filler. The end of that CD features a significant bonus: three songs from their 1964 demo at Gold Star studios, including early versions of “Stick Like Glue” and “Still in Love With You Baby,” along with the fine and otherwise unrecorded “People Are Cruel.” The last of those songs set the template for their trademark bittersweet melodies and harmonies at their very first studio session. Also present is a 1964 rehearsal, “Believe Me I Can Tell,” that makes its first appearance here.

The disc of Sal & Ron recordings has the informal feel of sessions that would often be labeled as “unplugged” in much later decades. Fun to hear for big Brummels fans, and I’m one, the nonetheless don’t feature their best songs, and some are kind of sketchy compared to their tunes that found official release. Exceptions are an Elliott solo demo of “Don’t Talk to Strangers” and a Valentino demo of the Triangle highlight “Magic Hollow.” I’m not the biggest aficionados of mono single versions, but it’s good to hear so many of them in sequence on the final CD (including the canceled 1965 single “Gentle Wand’rin’ Ways”/“Fine With Me”), and there are some differences audiofiles will pick out, like the longer cold ending of “Laugh, Laugh.” Valentino’s rare 1969 and 1970 solo singles (adding up to just four tracks) bring that disc, and the set, to a close.

Yes, there are just a few items that could have been added to make this set even more complete. Those include Elliott’s 1969 solo album Candlestickmaker (though that’s been reissued on CD) and the numerous songs he wrote or co-wrote that weren’t done by the Beau Brummels, but were cut by other artists, particularly by Butch Engle & the Styx. For recordings with direct Beau Brummels involvement, however, it’s not going to get better than this. And while the Beau Brummels’ corner doesn’t need to be fought to most or all Ugly Things readers, the box serves as evidence that they were one of the best American groups of their era, even if the mainstream media seldom acknowledges them as such. (This review will appear in an upcoming issue of Ugly Things magazine.)

5. Joni Mitchell, Archives Vol. 2: The Reprise Years 1968-1971 (Rhino). Like volume one, this is a five-CD set stuffed to the gills with unreleased material (with the exception of one track from a various-artists compilation and a couple snippets of between-song chatter). There are live tapes, BBC radio and TV broadcasts, home recordings, and a Dick Cavett Show appearance. In a significant difference from the first volume, there are also demos and outtakes from when she was signed to Reprise. The first volume didn’t have those, since everything on that box predated her first album.

I put volume one #1 on my 2020 list, and while this set is produced just as well, I don’t find it quite as compelling overall. It likewise fills in major gaps in her body of available recordings, but does, at least to my ears, have less notable differences between what’s already been long available in her early catalog. There’s plenty to enjoy on a pure entertainment level without getting into analytics, however, and these should first be emphasized before I point out some mild shortcomings.

There are a good number of songs that didn’t make her early albums, starting with “Midnight Cowboy” (two circa late 1967/early 1968 versions), done as an obscure cover by another artist, but never on her own records until now. It’s not a rival for the tune actually selected as the theme for the Midnight Cowboy movie, Harry Nilsson’s version of “Everybody’s Talkin’,” but still good to hear. There’s the slightly Bo Diddley-influenced “Dr. Junk,” though Mitchell wasn’t getting into rock accompaniment during this era, and most of the tracks are solo acoustic performances. The unusual late 1967/early 1968 demo “Roses Blue,” taped well before the song appeared on her second album, has what’s termed a Peacock harp overdub in the notes, creating an unusual spooky, slightly dissonant sound. There’s her cover—not a great one—of “Get Together,” as well as a bit of “Bony Maronie” that was (with “Big Yellow Taxi”) on the compilation Amchitka: The 1970 Concert That Launched Greenpeace. And there are a couple late-‘60s wordless scatted recordings at a friend’s apartment that actually count among the most interesting previously unavailable/unknown cuts, owing to their cool unusual melodies.

It’s good to finally hear the February 1, 1969 Carnegie Hall concert considered for official release in its entirety (oddly, the only previously released excerpts were the aforementioned bits of spoken chatter, heard on the sampler The 1969 Warner/Reprise Record Show). A few tracks from a September 1968 BBC radio session have mild band accompaniment, the musicians including the Strawbs’ Dave Cousins and Donovan associates John Cameron and Harold McNair. There are sometimes noteworthy differences in outtakes and demos of songs like “Woodstock,” “Urge for Going” (heard with strings), and “Ladies of the Canyon” (heard with cellos).

Through no fault of Mitchell or those who helped with the set, the fact remains that most of the songs that didn’t find a place on her early albums weren’t as good as the ones that did, although all have some merits. That’s what a top artist often does: pick the best tunes, and leave out some that are kind of similar to the best tunes, but not as good. The live performances, uniformly of a high standard, still often don’t vary much from the most familiar ones.

Although this runs counter to what most critics write about Mitchell’s early work, I find some of the later material here not as striking as her best previous efforts. I don’t favor her piano accompaniment, which she started to use with increasing frequency in this set’s latter stages, as much as her guitar work (though it’s nice to hear a few tracks with dulcimer). And as I’m not a big James Taylor fan, I’m not too hot on five October 1970 BBC radio duets with him, though they don’t put me off. So all told, the set falters a bit—not much—for me the later it goes in this admittedly small chronological span from the very beginning of her recording career.

This doesn’t mean this isn’t a major archival release that’s very good listening and very good value. In common with volume one, the booklet has a lengthy recent interview with Mitchell about the material on the box, as well as vintage illustrations/graphics and detailed source notes. It’s not #1 this time around, but it needs to be something I like a lot to get into the top five, where it’s placed this year. Although it should be noted that it’s known there’s even more from this era that’s not here, like the “Come to the Sunshine” and “Go Tell the Drummer” outtakes from her first album. This does have four outtakes from a January 1968 Song to a Seagull session, including one, the supremely haunting “The Gift of the Magi,” that should have qualified for an official release somewhere during this era, but didn’t.

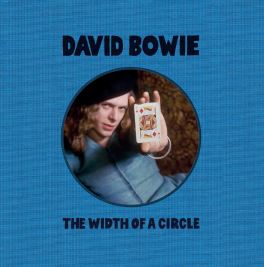

6. David Bowie, The Width of a Circle (Parlophone). Some multi-disc boxes, including some of Bowie’s, are bloated by mixes of well known albums done decades after their initial release, and/or a core album that many fans already have, often in more than one version. It’s refreshing, then, that Parlophone have basically put together two CDs of extras that could have been part of an expanded version of The Man Who Sold the World, but are issued separately here. If you want a remix of The Man Who Sold the World by producer Tony Visconti, it came out (titled Metrobolist) in 2020. The Width of a Circle is entirely devoted to material recorded around the same time as The Man Who Sold the World, but not actually on The Man Who Sold the World.

The Man Who Sold the World itself, first issued in 1970, was a major and underrated LP, and my favorite of Bowie’s. This set isn’t as good as the tracks on The Man Who Sold the World, but it’s well worth hearing. Disc one’s comprised entirely of a February 5, 1970 concert broadcast on the BBC, though just one song (“The Width of a Circle”) appeared on the forthcoming album. Musicians who’d have prominent roles on The Man Who Sold the World, Visconti and Mick Ronson, do play on some of the fourteen songs. They generally show Bowie moving toward a more rock-oriented and less folky sound, though some of his late-‘60s folkiness remains on the opening four solo performances.

Some of these songs are from his 1969 David Bowie aka Space Oddity album; one appeared on a flop non-LP 1970 single, “The Prettiest Star”; one had been recorded before Space Oddity but not yet released, “Karma Man”; and there were covers of Jacques Brel’s “Amsterdam” and songs by Biff Rose. Most of this was bootlegged a long time ago, but the sound quality here is much better than my bootleg from decades past, even if it’s taken from an off-air cassette recorded by Visconti. The performances are good and straightforward, and if “An Occasional Dream” in particular is not as affecting as the unreleased folkier one he did with John Hutchinson on second guitar and vocals in 1969 (available on the Conversation Piece box), it’s less fruity and hence better than the Space Oddity version. In all, it’s a good snapshot of a transitional phase that’s refreshingly free of songs that circulate in numerous other live versions.

Disc two is a little patchier, combining his soundtrack for the 1970 Scottish TV program Pierrot in Turquoise or The Looking Glass Murders; obscure non-LP 1970 singles; four songs from a March 1970 BBC session, only one of which came out on Bowie at the Beeb; and, alas, five superfluous “2020 mixes” (only one of which, the single edit of “All the Madmen,” is of a song not otherwise on the set). Less interesting than disc one, disc two is still valuable for his faintly pre-glammish non-LP singles “The Prettiest Star” (the original version, not the remake on Aladdin Sane) and “Holy Holy”; the two-part version of “Memory of a Free Festival” on a single, different from the Space Oddity version; and the spooky organ-paced version of “When I Live My Dream” from The Looking Glass Murders. The March ’70 BBC session has a version of the Velvet Underground’s “Waiting for the Man,” though it’s not nearly as interesting as the previews of “The Width of a Circle” and another song from The Man Who Sold the World, “The Supermen.”

At a glance this seems like it might be a definitive supplement to The Man Who Sold the World, but it isn’t quite. “The Prettiest Star” 45 is presented in an “alternative mix” and a “2020 mix,” but not the original mix, if you’re a purist determined to hunt that down. The liner notes, which are very good and detailed, note that there was an unsuccessful attempt to record “The Supermen” in the studio a couple days before it was played on the BBC. It also refers to a cassette demo of “Holy Holy” “helping to secure Bowie his new music publishing deal.” I don’t think the compilers of archival anthologies like this intend to frustrate collectors who want to hear everything, but sometimes it feels that way.

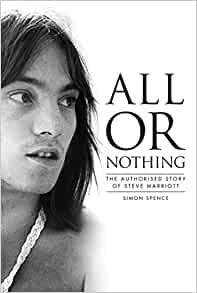

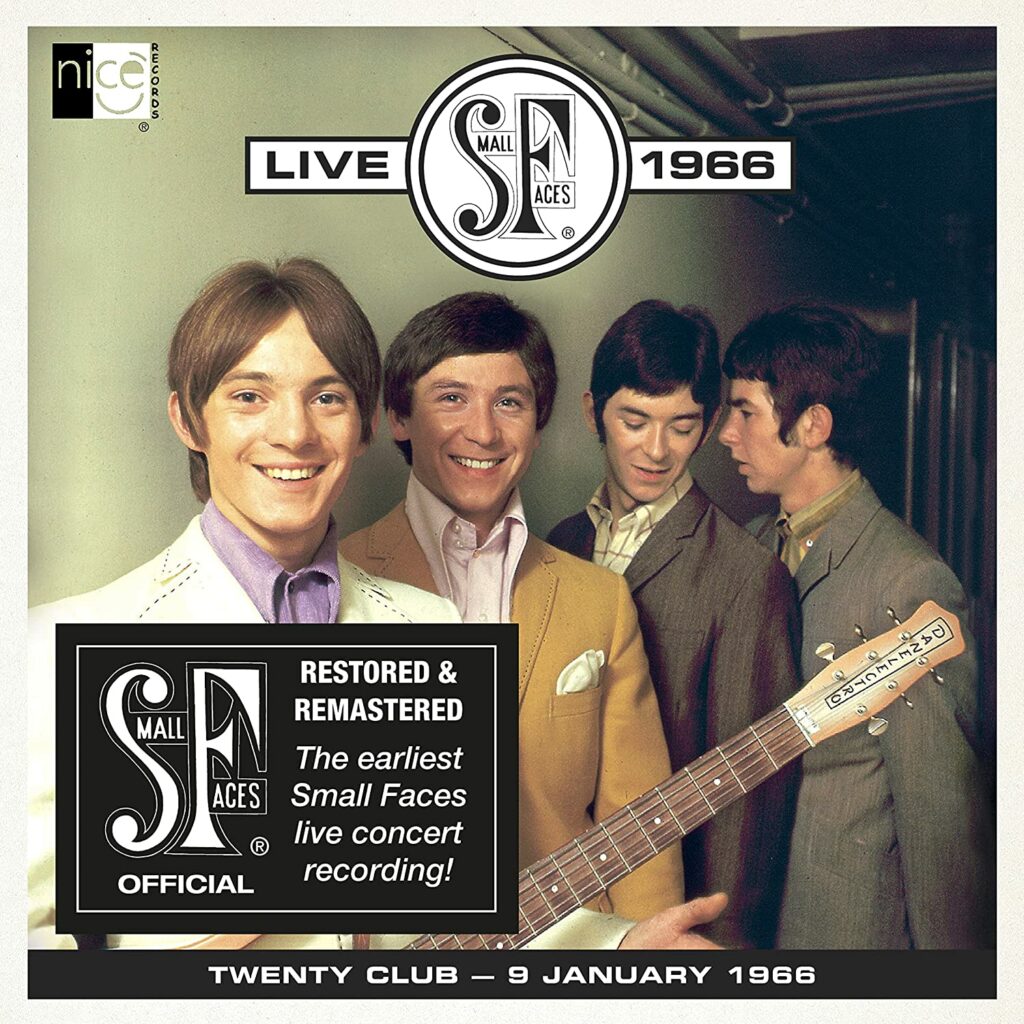

7. The Small Faces, Live 1966 (Nice). True, the sound on this isn’t great, with some imbalance and dropouts, though it’s pretty listenable. Also true: that doesn’t matter much, since this is a tremendous legitimate release of two shows the Small Faces played at the Twenty Club in Mouscron, Belgium, on January 9, 1966. That only adds up to fourteen tracks, but that’s enough for a satisfying full 55-minute CD, even though four of the songs were played twice. Included are two versions of their first hit single, “What’Cha Gonna Do About It”; the B-side “Grow Your Own”; the medley “Plum Nellie,” which at nine minutes is much longer than the one on From the Beginning, with excerpts from “Baby Please Don’t Go,” “Parchman Farm,” and “Land of 1000 Dances”; and a few numbers that would soon be on their debut LP, most notably “You Need Loving” (again two versions), which provided some of the basis for Led Zeppelin’s “Whole Lotta Love.”

Even better, this has a few songs they wouldn’t record in the studio, all covers: Jesse Hill’s “Ooh Poo Pah Doo” (admittedly a very short version), James Brown’s “Please, Please, Please,” the obscure Larry Williams tune “Strange,” and a storming instrumental treatment of “Comin’ Home Baby” (two versions) spotlighting Ian McLagan’s organ. The real star of the show, however, is Steve Marriott, whose full-throated soul-rock vocals are as magnificent here as they ever were. His raw lead guitar’s pretty impressive too, and his brief between-song patter bubbles over with exuberance. This is a terrific document of the group at their most raucous R&B-rock beginnings (even predating the release of their first really big British hit single, “Sha-La-La-La-Lee”), from a period where not many such quality live recordings survive of major British Invasion acts. The liner notes aren’t huge, but they give as much succinct detail as the release warrants, including a couple pages of memories from drummer Kenney Jones.

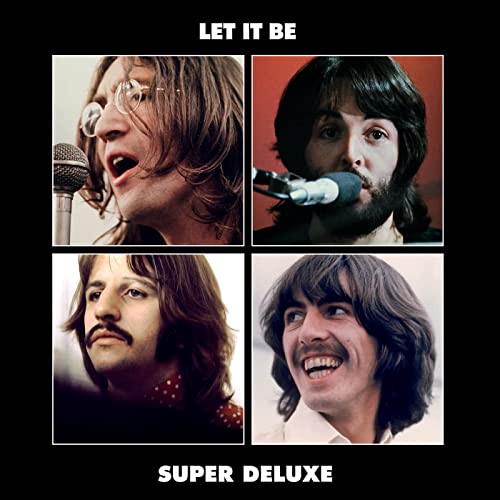

8. The Beatles, Let It Be super deluxe edition (Apple/Universal). If this list was being made in 1970, Let It Be would rank higher. It’s been dumped on by lots of critics and others in the last half century, but the Beatles at less than their best are still better than almost anything else. There were three great hit singles (“Get Back,” “Let It Be,” and “The Long and Winding Road,” the last of which was albeit much better in its original form without orchestral/choral overdubs); some very good other songs (“Two of Us,” “Across the Universe”); and most of the other songs were decent (“I Dig a Pony,” “I’ve Got a Feeling”). Even the run-of-the-mill ones by Beatles standards (“For You Blue,” “One After 909”) were okay. It did lack the unity and consistency a typical Beatles album, in part because the original concept of playing live without no overdubs got diluted.

About 100 hours of tapes from their January 1969 recordings for the album (originally titled Get Back, and then delayed for more than a year) have been in unofficial circulation for a long time. So there was plenty of material to choose from for a six-disc box set expanded edition. That has to be judged, however, not solely on the original album, which is part of the box as a CD and a Blu-ray. It has to be considered whether it makes the most of an opportunity to add the best previously unreleased recordings. Sure, everybody, insiders or fans, would come up with a different track selection given that such a commercial box can’t be 100 CDs, or anything close to that. Still, to trot out a cliché, if this is all we’re going to get, in many ways it’s a lost opportunity.

Most of the previously unavailable stuff (though a bit of the extras have come out on archival releases like Anthology 3) is on two CDs: “Get Back—Apple Sessions” and “Get Back—Rehearsals and Apple Jams.” If you’ve never heard them before (though many Beatles fans have), they’re interesting, if not on par with what made the original LP. There are different versions, usually looser (sometimes quite a bit looser), of most of the songs from the album. There are also unpolished runs through some songs that didn’t, like “All Things Must Pass,” “Gimme Some Truth,” and Abbey Road works-in-progress like “Oh Darling,” “Octopus’s Garden” (on piano), “Polythene Pam,” and “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window.” The brief version of “The Walk,” familiar from the earliest bootlegs from these sessions back in 1969, is here. Note that the version of “Something” is such a tentative fragment that it’s more notable for dialogue between George and John about getting stuck on the lyrics than for the music.

Another of the bonus CDs has the “1969 Glyn Johns Mix,” although Johns, an engineer and co-producer for Let It Be, actually did a few mixes. This is probably the one that came closest to being released, and has a few different takes; more between-song dialogue; and a generally looser, more live feel that was more in keeping with the original Get Back concept than the eventual Let It Be LP. It’s missing the Phil Spector orchestral/choral overdubs; has a couple brief and unimpressive oldies jams not on Let It Be; includes a Paul McCartney song (“Teddy Boy”) that also wouldn’t make the final cut, though it would be on McCartney’s debut solo album; and is missing “Across the Universe” and “I Me Mine,” which did make Let It Be. Got all that?

Johns’s 1970 mixes of “Across the Universe” and “I Me Mine” are on another of the CDs, titled Let It Be EP. This only has four songs, the others being new mixes of “Don’t Let Me Down” and “Let It Be.”

Even if it was felt that the CDs of the original LP and the Glyn Johns mix needed to be standalone discs, the running time for a six-disc set is shamefully short (and, arguably, the audio-only Blu-ray version of Let It Be unnecessary). The two sessions/rehearsals/jams discs add up to only about 73 minutes, and could have easily fit on one CD. The EP-CD is just over 13 minutes. The set has poor overall value for the hefty price, and more importantly, omits a good deal of material that’s arguably at least as interesting as what was selected, and could have fit on a six-to-eight-disc box.

Examples include: their entire live rooftop concert from January 30, 1969 (though some of it was used on the LP); the earliest Johns acetate mixes from January 1969, which were the truest to the rough’n’ready original concept and have a way-cool take of “Let It Be” with a great McCartney count-in (and have long been bootlegged); a version of “Get Back” with John Lennon on lead vocals; a ragged-but-cool version of “I’m So Tired” with Paul McCartney on lead vocals, though that song had already been on The White Album; a good McCartney-sung cover of “Singing the Blues” (albeit with an intrusive announcement from a film technician partway through); the fast version of “Two of Us” seen in the Let It Be movie; a different, very humorous version of “Two of Us” with exaggerated Liverpool accents; George Harrison’s solo demo of “Isn’t It a Pity,” which has only been available on iTunes; and George’s nice version of Bob Dylan’s “Mama, You’ve Been on Mind,” even if the vocals are kind of faint. It’s true that a great deal of the rest of the 100 or so hours of vault material are redundant similar-sounding rehearsal versions and subpar, fragmentary passes at rock’n’roll oldies. But this box certainly isn’t going to make the bootlegs redundant, even if what small percentage of unreleased material was unveiled has better sound quality than the boots.

You want a consolation prize? There’s actually a good one in the box. The 108-page hardback book is very good, with detailed information about the sessions and the whole Get Back/Let It Be project, and plenty of photos. It’s entirely different from, and better than, the photo-dialogue-oriented Get Back book issued to coincide the Peter Jackson documentary on the Get Back saga and this box.

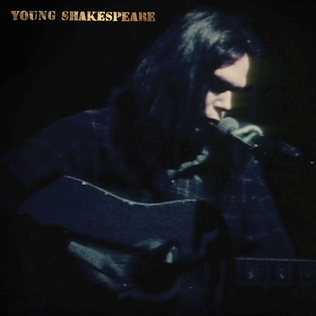

9. Neil Young, Young Shakespeare (Reprise). Recorded on January 22, 1971 at the Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford, Connecticut, this is a fine-sounding live concert from a tour on which Young played everything solo on acoustic guitar and piano. While this is prime Young and the dozen songs are all classic and famous (with the possible exception of “Dance Dance Dance”), it’s a little less exciting of a discovery in 2021 than it would have been in, say, 1981, or even 2001. A bunch of very similar shows from the time have circulated officially or unofficially, and some of those other batches are longer with some songs that don’t make this release, like “See the Sky About to Rain” and “I Am a Child.” Judged on its own—though it’s unlikely many people are going to buy this without having heard some of those other performances—it’s excellent, the solo format marking them as notably and enjoyable different from the familiar, usually full-band studio versions. It’s a little odd to hear the audience clap along at points, though it doesn’t interfere with the music.

Included with this release is a DVD of footage from this very concert. It’s not significant enough to merit inclusion on my best-of-film list for the year, as it seems to have been filmed (albeit in color) with home movie-type equipment. You hate to use the term “shaky” considering that’s Bernard Shakey’s a pseudonym Young uses for his film projects, but it sure is. Maybe it was filmed informally with no intention of it being used for anything official, though there aren’t liner notes to illuminate the back story. Interspersed with the footage are a few brief non-concert clips (over which the concert recording plays), none remarkable – a river is shown during “Down By the River,” an elderly man talking to Young during “Old Man,” and the like. And “Sugar Mountain” is incomplete, though it runs the full eight-and-a-half-minutes on the CD.

10. Dusty Springfield, The Complete Atlantic Singles 1968-1971 (Real Gone). This compiles the original mono 45 versions of all the tracks on the singles Springfield issued on Atlantic from 1968-71, when she did her best US sessions and was at her peak as a pop-soul singer. It’s a good anthology, but note that if you’re a Springfield fan/collector, you should evaluate how much original mono versions mean to you, as all of the songs have been available on CD elsewhere (on Rhino’s expanded versions of the Dusty in Memphis and A Brand New Me albums, for instance). Whatever your preference for mono or stereo, it functions as something of a best-of for Springfield in this period, even if just one track (“Son of a Preacher Man”) was a big hit. There are plenty of cuts almost on that level here, though the best tend to be from Dusty in Memphis, like “Breakfast in Bed,” Randy Newman’s “I Don’t Want to Hear It Anymore,” and Bacharach-David’s “In the Land of Make Believe.” For those who don’t have big Springfield collections, much of this will have been previously obscure to them, especially the material postdating Dusty in Memphis, though these include sessions produced by renowned producers Kenny Gamble, Leon Huff, Ellie Greenwich, and Jeff Barry. Excellent lengthy liner notes augment the fine 24-track package.

11. John Lennon, Plastic Ono Band: The Ultimate Collection (Capitol). Although his first few singles were credited to Plastic Ono Band and his first full studio album was officially titled John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band, it’s roundly regarded as Lennon’s first proper solo LP. Upon its release in late 1970, it gained huge media attention, and usually great reviews, for its spare and cathartic self-examination of his tortured childhood and shedding of his identity as a Beatle. Some pretty love songs and jauntier observations were mixed in too. But its generally somber, bone-cutting air meant it didn’t sell nearly as well as the 1970 albums by his old chums George Harrison and Paul McCartney.

Plastic Ono Band wasn’t nearly as involved a production as the Beatles’ post-1965 LPs—or, for that matter, Harrison’s All Things Must Pass. It was completed in about a month, the bulk of it cut in little more than a half dozen separate sessions. There wasn’t much orchestration or embellishment of basic guitar, vocal, piano, bass, and drums. But although there wasn’t as much experimentation, multi-tracking, overdubs, and such as there had been on late-‘60s Beatles albums, there were plenty of alternate takes. The sheer size of this eight-disc set testifies to that, though the alternates are bolstered by some demos, home tapes, jams, and non-LP singles.

Essentially this presents the original album; the three 1969-70 singles “Give Peace a Chance,” “Cold Turkey,” and “Instant Karma”; and no less than six pseudo-alternate versions of the record. Each of those six discs presents different versions of each of the LP’s eleven songs in sequence, as well as different versions of those singles. There’s also a disc of off-the-cuff jams from the sessions, most of them brief covers of rock’n’roll oldies.

With more than eleven hours of music, this “ultimate collection” seems at a glance to be the ultimate gift for the Plastic Ono Band fanatic. Generally it is, but there’s a bit of “be careful what you wished for” attached. Many of the alternate takes aren’t much different from the finished versions, Lennon often having a good idea of the arrangement before work started on a specific song. And there’s virtually nothing in the way of original compositions that didn’t make the album.

Perhaps more problematically for the purist, there are “elements mixes” that highlight and/or subtract ingredients from the LP tracks. As more of a challenge, there are also “evolution mixes” that aim to sort of present audio documentaries of how recordings came together by editing together excerpts of various takes. These mixes are a very twenty-first century way of doing things, giving us an inside (if selective) look that’s never before been available, but in a format that’s not something you want to groove to for fun or many repeat plays.

The standouts are the cuts that are substantially different from the ones on the long-available original album, though a good share of these have come out on Lennon’s Signature and Anthology boxes, as well as his Acoustic collection. In particular, his somewhat lo-fi summer 1970 demos, recorded at the home he and Yoko were renting in Bel Air while they took Arthur Janov’s primal therapy, have a bare and spooky ambience yet more chilling than the relatively polished studio counterparts.

Not all of the songs from Plastic Ono Band were demoed in this form, but the majority were, featuring just John and his guitar, which sometimes boasts a shaky, eerie tone. The compositions he taped at this juncture were in largely finished form, though a few (“Remember,” “Isolation,” “Hold On,” and “”Working Class Hero”) are absent and might not have yet been written. Had these been demoed in the same form, you’d have a complete alternate pre-Plastic Ono Band album of sorts yet rawer and more harrowing than the actual LP.

As for alternates from the studio sessions, there are just a few that stand out as both significant variants from the familiar versions and performances of considerable merit. It’s interesting to hear guitar, not piano, as the dominant instrument in “Mother”; a solo piano rendition of “Isolation” that, maybe uniquely among these outtakes, is an arguable match for the full-band album version; and “Love” with just acoustic guitar, sometimes fingerpicked, sometimes strummed. Part of the main value in hearing the numerous less striking outtakes are frequent reminders that, soul-searching serious lyrics to the contrary, Lennon was often in a jovial mood during the sessions. He frequently jokes and banters with drummer Ringo Starr, bassist Klaus Voormann, and others. “So if you ever change your mind…or the rhythm,” he improvises during take 1 of “Remember,” for example.

Like the many bootlegged tapes of the Beatles covering oldies during the January 1969 Get Back sessions, the disc devoted to jams—largely on songs by the likes of Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Elvis, and Carl Perkins—looks better on paper than it sounds in reality. They were more a way to keep loose between takes, or warm up to back Yoko on the October 10 session that yielded her Plastic Ono Band album, than serious attempts at something that would find release. (The unedited tracks from those sessions for Yoko’s album, incidentally, are on the Blu-ray part of the set, along with Yoko’s three B-sides on the Plastic Ono Band’s early singles, one of which, “Don’t Worry Kyoko,” is presented in a longer, nine-and-a-half-minute version. There’s also a different two-minute version of “Don’t Worry Kyoko.”)

John and his friends do play with more tightness and conviction on the jams than the Beatles often managed during their largely lackluster Get Back sessions covers, however. But don’t get too excited by the presence of an early version of Imagine’s “I Don’t Want to Be a Soldier.” At this point, Lennon had little more than the title lyric.

As always, completist collectors can second-guess the selection even for a box of this size. The Signature box alternate take of “God,” which starts with a scarifying “WELLLLL BROTHER” and still cites “Dylan” rather than “Zimmerman,” is missing. From bootlegs, so is the admittedly slight “When a Boy Meets a Girl,” which is usually attributed to the summer home demos. So are a few home demos of “God,” which John recorded in four versions, not just the one on the box—another is available on Acoustic, and others only circulate unofficially.

Then again, along with the dozens of tracks that have never before circulated, there are neat throw-ins like informal non-studio tapes of “Give Peace a Chance” and “Remember,” and home demos of “Cold Turkey.” The accompanying 132-page book has thorough details on the sessions and tracks, along with many quotes from John, Yoko, and sidemen and studio staff (some contributed specifically for this project). It’s frankly kind of a headache to keep all the elements/evolution/”raw” mixes straight, but spacing the alternate versions out into discs that follow the LP sequence helps. (This review originally appeared in the summer 2021 issue of Ugly Things magazine.)

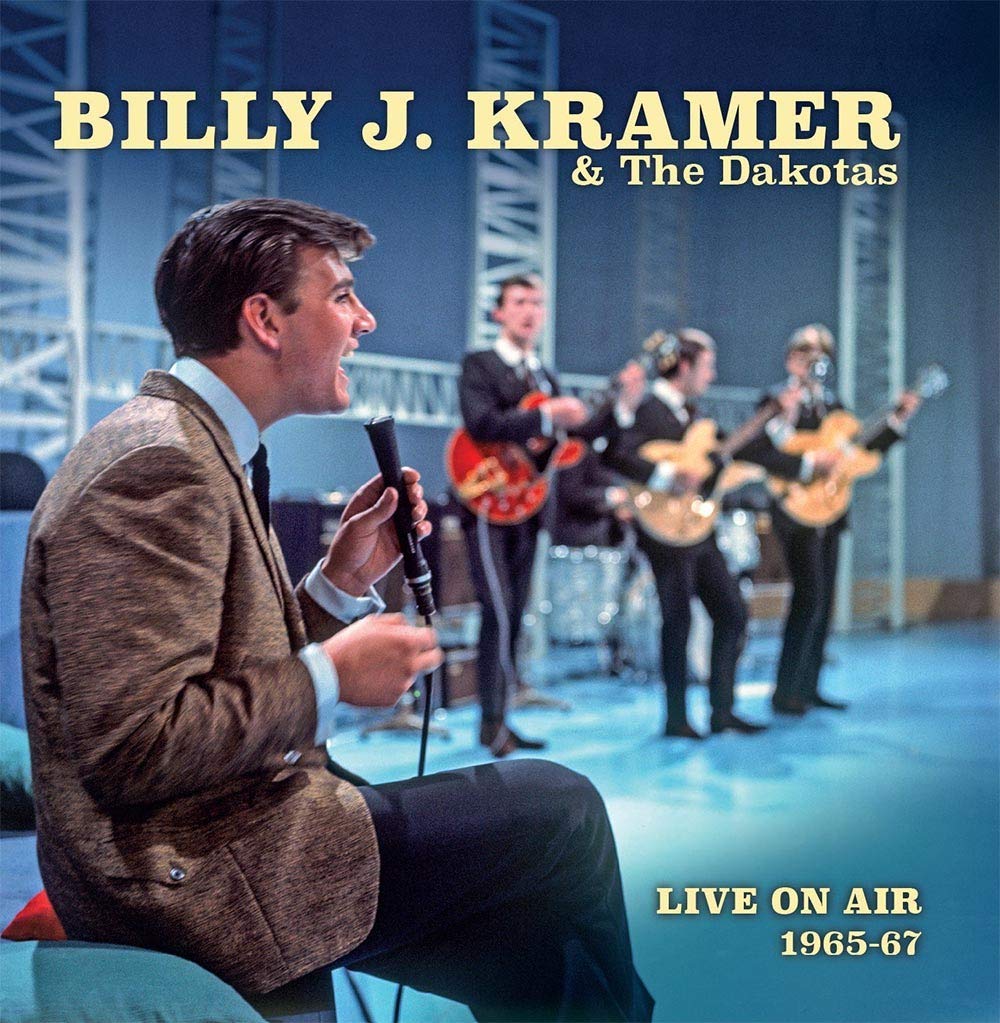

12. Billy J. Kramer & the Dakotas, Live on Air 1965-67 (London Calling). Praising Kramer isn’t going to win you many hip points even among British Invasion obsessives, but he made his modest contribution to one of the great waves in twentieth century popular music. Some of it’s captured on this double CD of 1965-67 BBC sessions, though no doubt some earlier radio sessions are missing, as his popularity peaked in 1963 and 1964. There’s just one of his covers of Lennon-McCartney songs the Beatles didn’t release (“From a Window”), for instance, and while the big hit “Little Children” is here and “Trains and Boats and Planes” was his last big British single, most of this will be unfamiliar even to those who have some Kramer in their collections. Quite a few of these are covers that didn’t appear on his records, though they tend to be forgettable, routine covers of oldies like “Hello Josephine,” “My Babe,” and “Milk Cow Blues.” He did try some contemporary material, though his versions of Bob Dylan’s “It’s All Over Now Baby Blue,” “Land of a Thousand Dances,” Roy Head’s “Treat Her Right,” and (more surprisingly) Bobby Darin’s “We Didn’t Ask to Be Brought Here” are unremarkable, or a little worse.

Better are the mild and tuneful pop-rockers that were more his stock in trade—not just the hits already mentioned, but also “It’s Gotta Last Forever” (two versions) and the Drifters-like “Neon City,” probably his best post-hit piece of material. And he and the Dakotas rock surprisingly hard and well on Ricky Nelson’s “Sneakin’ Around,” probably their best relatively tough tune. They certainly must have thought so – there are no less than three 1965 BBC versions here. Kramer had his vocal limitations, and the Dakotas weren’t among the era’s most exciting instrumentalists (though ex-Pirate Mick Green was with them for a while). But they did ultimately offer competent singing and playing on their period Merseybeat, which at its best, here and elsewhere, is genuinely entertaining, if not near the same league as the best acts of the British Invasion’s first wave. The sound quality here is excellent, but unfortunately the liner notes aren’t, giving a basic historical overview but no specific description of these radio broadcasts (which at least are dated), and not even any songwriter credits.

13. Colosseum, Transmissions: Live at the BBC (Repertoire) Blues-rock-jazz outfit Colosseum’s commercial success was modest, amounting to four albums that made the lower reaches of, or almost made, the UK Top Twenty in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. The BBC certainly loved them, however, as sessions spanning January 1969 to September 1971 fill up six entire CDs on this set. It makes for both rewarding and frustrating listening, since they could be invigorating at their best, but were pretty exhausting at less than their best.

Colosseum were formed by two veterans of the Graham Bond Organisation, drummer Jon Hiseman and saxophonist Dick Heckstall-Smith, who also played in the late-’60s Bare Wires lineup of John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. At their most accessible, Colosseum unsurprisingly sounded rather like late-period Graham Bond Organisation, but with a greater jazz/progressive rock flavor.

That often comes through well on the first year or so covered by these radio sessions, especially on the Bond composition “Walking in the Park,” which of course had been a highlight of the second Bond LP back in 1965. There are no less than five versions here—well, you can’t blame a band for delivering their most famous song over and over—and the interplay between organ and wah-wah guitar on “Elegy” (also represented by five versions) was another highlight of their early repertoire.

One clichéd view of British rock during this era is that it got steadily less interesting as it got heavier and more self-indulgent with the dawn of the ‘70s. That doesn’t always hold true, but unfortunately, it pretty much does for Colosseum, though their instrumental proficiency was never less than top-notch. Even over the course of these two-and-a-half years, as heard on these sessions, they got progressively prone to longer and less focused songs, overlong riffing, and some of the lengthier drum solos of the period (as good as he was, Hiseman was one of the chief offenders in that regard).

Some opinions on the matter differ greatly from mine, but the introduction of Chris Farlowe into the group in 1971 was not a plus, although he had by far the greatest British commercial profile of anyone in their frequently fluctuating lineup. His vocals were overwrought, and in fact Colosseum’s singing had gone in that direction since original guitarist-vocalist James Litherland was replaced in mid-1969.

The underrated Litherland was also responsible for some of their better original tunes (like “Elegy”), and composing was never among their chief strengths. Perhaps unsurprisingly given their common roots in the Graham Bond Organisation, Colosseum also took a crack at a couple Jack Bruce-Pete Brown collaborations that were among the most popular tracks from Bruce’s first solo LP, “Theme for an Imaginary Western” and “Rope Ladder to the Moon.”

There’s an abundance of multiple versions here, as you’d expect from such a lengthy comp covering just under three years, though the group did often noticeably vary the arrangements. There aren’t many songs that didn’t make their first few albums, though a couple such originals from the final (September 1971) session here, the gloomy “Sleepwalker” and “Upon Tomorrow,” were so obscure that organist/vibraphonist Dave Greenslade had a hard time remembering them when giving his commentary for the liner notes.

Among the other extras, “Shades of Blue,” written by British jazz pianist Neil Ardley, is such pure Kind of Blue-type jazz that it sounds like a different group—and sort of was, since it’s probably just guitarist Dave Clempson with the New Jazz Orchestra. From 1969, “Hiseman’s Condensed History of Mankind” is a percussion-dominated instrumental that verges on the avant-garde, and unsurprisingly didn’t make the cut for a studio LP.

While this BBC anthology (and Colosseum’s catalog as a whole) makes for mixed if occasionally exhilarating listening, this set’s comprehensive packaging can’t be faulted. The sound’s very good, and room’s made for a session of unknown date and origin (from late 1969 or early 1970) and an off-air March 1969 recording of “Walking in the Park.” The 44-page liner notes draw extensively from interviews with surviving members (as well as Greenslade’s comments on numerous specific tracks), and the band show more interest than most veterans in going over the kind of details that the sort of specialists who buy these collections want to hear.

Also recently issued by Repertoire, and featuring detailed liner notes, were individual releases of five different concerts: Live at Montreux International Jazz Festival 1969; Live at the Boston Tea Party (in 1969); Live at Ruisrock Festival, Turku, Finland 1970; Live at the Piper Club, Rome, Italy, 1971; and Live 1971 (unlike the others, a double CD, from three concerts in England in March of that year). Most (though not quite all) of the songs on these were also done in BBC versions on Transmissions, and the sound quality is reasonable on all of them, with the exception of the lower-fi Live at the Piper Club. But as the fidelity’s better, and the performances more precise, on Transmissions, these are for the harder-core Colosseum fan. (This review originally appeared in the summer 2021 issue of Ugly Things magazine.)

14. The Merseybeats/The Merseys, I Stand Accused: The Complete Merseybeats and Merseys Recordings(Grapefruit). Never entering the charts in the US, but among the more successful Liverpool ‘60s groups in the UK, the Merseybeats have been fairly well served by reissues. Virtually all of their 1963-65 recordings were on Bear Family’s I Think of You CD comp. The numerous discs by their spin-off groups haven’t been so fortunate, with even the Merseys’ 1966 #4 hit “Sorrow” hard to find on reissues.

This double-CD anthology totally rectifies the situation. Besides all everything the Merseybeats released in the ‘60s, there’s everything from all six of the 1966-68 singles by the Merseys, who featured singer-guitarist Tony Crane and bassist-guitarist Billy Kinsley from the Merseybeats; a previously released alternate version of “Sorrow” and a 1966 Merseys track (“Nothing Can Change This Love”) that was unissued at the time; two mid-‘60s solo 45s by Johnny Gustafson, who replaced Kinsley in the Merseybeats for a while; the 1966 single by Johnny & John, which paired Gustafson with Merseybeats drummer John Banks; the 1969 single by the Crackers, who were the Merseys under a different name; two late-‘60s singles by the Quotations, who were fronted by Gustafson; and a 1964 demo by the Kinsleys, Billy Kinsley’s group when he briefly left the Merseybeats. As if that’s not enough for a breathless paragraph-cum-list, there are also a few Merseybeats demos and outtakes that didn’t make I Think of You.

From a completist collector’s viewpoint, you couldn’t better this comp. For quality and consistency, however, it has to be cautioned that this is an uneven overview of a group who, despite nabbing a prime band name and sporting the best visual image of any Liverpool group save the Beatles, were rather musically ordinary. Favoring slow ballads and midtempo numbers spotlighting their fine harmonies, and not writing much original material, the Merseybeats were far below the Beatles and the Searchers on the local totem pole, and for that matter not quite up to the more energetic fare of the Swinging Blue Jeans and Mojos. The Merseys went into a more vaguely mod-pop direction, but never offered anything else on the level of “Sorrow.”

Most of the Merseybeats tracks are on the 34-track first disc. Although that number might sound exciting if all you have is Edsel’s well-chosen 16-track Beat…and Ballads, that 1982 best-of had most of their noteworthy material. Among the standouts were their Merseyfied covers of the Shirelles’ “It’s Love That Really Counts” and “Don’t Let It Happen to Us”; “Last Night,” their catchiest and Mersey-est non-cover, though it barely made the UK Top 40; the fair pop-rock of “Don’t Turn Around,” which like their version of “Wishin’n’Hopin” made the British Top Twenty; a couple decent midtempo originals in “Milkman” and “See Me Back”; their 1963 debut 45 “Fortune Teller,” one of the few times they more or less rocked out; and the rambunctious soul-pop of their final 45, “I Stand Accused.”

The LP and EP tracks that round out their discography were relatively forgettable for the most part, including some really naff covers, as well as a couple German-language versions of their hits. Exceptions were a surprisingly rocking redo of Rodgers-Hammerstein’s “Hello, Young Lovers” done Ricky Nelson style, and the catchy 1964 outtake “The Things I Want to Hear,” another Shirelles cover that’s one of their better tracks. It and a few other rarities, like the 1962 demos of Everly Brothers songs, previously appeared as part of the Unearthed Merseybeat series. So did the sole Kinsleys track, “Do Me a Favour,” which would be redone with different lyrics and fuller production by the Swinging Blue Jeans as “Promise You’ll Tell Her.”

The Merseys track bound to attract the most attention is the alternate version of “Sorrow” (likewise previously heard on Unearthed Merseybeat), which included Jimmy Page, Jack Bruce, and John Paul Jones as backup session men. It’s a little, but not enormously, more rock-oriented than the more orchestrated hit 45, and lacks the memorable “with your long blond hair, I couldn’t sleep last night” coda. After such a strong start, you’d think that their other singles wouldn’t be as bland, but only “So Sad About Us” (issued a few months before the Who’s superior version) stood out, and then only slightly. The spin-off singles by Gustafson’s projects are unremarkable period British pop-rock with shades of soul, blues (“Mark of Her Head” can’t help but recall the Yardbirds’ “The Nazz Are Blue”), and even Tom Jones. The Quotations’ 1969 single “Hello Memories” has the strongest melody, though it was done better by the Irish group the Concords the following year.

You’d have to lay out a lot of bread, not to mention spend untold hours of time, to find the rarer singles on this anthology—even the ones by the Merseys, whom have never before been honored with a compilation that legitimately issues their output. The story’s told well in the abundantly illustrated 24-page liner notes, with quotes from Kinsley and Crane. Be prepared, however, for an experience that’s as much now-I-know-what-that-sounds-like as a vital musical document, though the Merseybeats/Merseys made some notable records at their best. (This review originally appeared in the summer 2021 issue of Ugly Things magazine.)

15. The Sorrows, Pink, Purple, Yellow & Red: The Complete Sorrows (Grapefruit). When I found the Sorrows’ 1982 Take a Heart compilation on the Australian Raven label shortly after its release, I would have been amazed and excited to learn that there were four full CDs of Sorrows material. They were one of the best mid-‘60s British groups never to have a US hit, and in fact they didn’t have much success in the UK, save for almost making the Top Twenty with “Take a Heart.” But while they weren’t the most original band around, they were a very good one, combining hard R&B and mod pop to electrifying effect on the mix of fourteen or so originals and covers on the Take a Heart compilation.

Almost forty years later, a four-CD Sorrows box is here, and while that sounds exciting, most of the music isn’t amazing. Here’s the hard fact to swallow: that Australian compilation, while terrifically consistent, collected all of their best tracks. Not only that, it collected almost all of their noteworthy ones. They did record some other material in their mid-‘60s prime, but the non-Take a Heart songs from that era were so-so. After multiple and hard to follow personnel changes, the Sorrows had by the end of 1967 turned into an almost entirely different band with the same name, with only tenuous links to the personnel from their peak. They did quite a bit of recording in Italy (sometimes in Italian) in the late 1960s, but at that point were a journeyman British rock band, whose average-to-below-average records were filled out with faceless covers of songs by Traffic, Family, and the Hollies.

There are a lot of extras here besides the mid-‘60s tracks that have been reissued elsewhere on CD a few times. There are some surprisingly dull 1964 demos for producer Joe Meek; stereo versions of songs from their first LP; a few Italian and German versions of early efforts; rare Italian-language singles from before they started to really go downhill; and a CD and a half of the late-‘60s sides from Italy, some from their Italy-only LP Old Songs New Songs, some from singles, some from side projects, some from demos, including a 1969 acetate demo LP. Lo-fi tapes from a 1980 reunion show serve no purpose other than to fill out the final CD.

As I am a big fan of their best mid-‘60s releases, it pains me to say that most of these extras are dull period late-‘60s British rock without distinguishing characteristics. An exception, sort of, is the garage-pop of the previously unreleased 1966 outtake “Ypotron.” I kind of like the weird baroque-mod-rock of “Pioggia Sui Tuo Viso #2,” from a promo-only soundtrack recorded in late 1966. It’s slim reward for such a big set. Is there another reason to buy this instead of that old Take a Heart comp? Well, the 24-page liner notes are incredibly thorough, and do a great deal to straighten out the twisted history of a band who have previously been surprisingly poorly documented, considering the quality of their best work.

16. Norma Tanega, Walkin’ My Cat Named Dog (Real Gone). The 1966 debut album by this quirky folk-rock-pop singer-songwriter has been on CD before, but this has considerably better sound and adds two songs from a non-LP 1967 single. It also has lengthy historical liner notes, by yours truly. So maybe this isn’t an unbiased assessment, but I hope its placement on this list is where it would have been ranked had I not been associated with the package. Tanega is mostly known for the novelty-tinged title track, which was a #22 hit. But her album was a varied if uneven mix of folk, rock, gospel, soul, and orchestral pop production, though winsome, earnest folky singer-songwriting with a dash of introspective melancholia was the most common (and best) element. The B-side of the non-LP 45, “Run, On the Run,” is easily the most unusual track she recorded during the period, mixing near-salsa beats, spy move horns, and fuzz guitar.

17. Various Artists, It’s a Good, Good Feeling: The Latin Soul of Fania Records (The Singles) (Craft Latino). Although the Fania label is mostly known for salsa music, from the late 1960s through the mid-1970s, it also put out a lot of boogaloo, or Latin soul. That’s a mixture of soul music with Latin jazz, which was very popular in the Latino community, though it didn’t make much of an impact with the general pop audience with the exception of a couple chart singles by Joe Cuba of “Bang Bang” fame. Cuba didn’t record for Fania, so he’s not here. But this four-CD (plus a bonus 45), 89-track compilation has plenty of other efforts in the genre from 1967-1975, all taken from singles, and many or all fairly rare and hard to find as far as I can tell. A few of these performers made a wider mark when they did straightahead Latin music, like Ray Barretto, Willie Colon, and the Fania All Stars. Most of them, however, aren’t so well known to soul fans, or in some cases to many collectors whatever their specialties.

Here are the obligatory criticisms to explain why this isn’t higher on the list. Many of the tracks are fairly similar in their uptempo party fusion of period soul music with Latin rhythms, horns, and melodies. Sometimes they’re pretty derivative of straight soul artists like the Temptations and the Average White Band. The Latin flavor is less prominent on the early-to-mid-‘70s selections, often sounding like pretty average if competent period soul. At the same time, however, the relentless party feel, varied with a few sentimental ballads, is pretty infectious and fun, though maybe four CDs is too much to take at once. There are some standout tracks, especially when it gets less formulaic, like Barretto’s “Soul Drummer” or the Harvey Averne Band’s slightly psychedelic instrumental take on Sly Stone’s “Stand.” Even the more generic cuts are usually pretty pleasing, and sometimes a little similar to the brown-eyed soul of the time in Southern California’s Latinx community, though that branch of Latino soul was far less jazzier and horn-oriented. With extensive liner notes, this compiles an important part of the catalog of a notable genre that hasn’t been nearly as thoroughly explored on CD reissues as most forms of soul have.

18. Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Déjà Vu 50th Anniversary Deluxe Edition (Rhino). The only studio album CSNY made in their original (and short-lived) incarnation before breaking up was a huge hit, reaching #1 in May 1970 with two Top Twenty singles, “Woodstock” and “Teach Your Children.” Presenting just ten songs by four prolific songwriters, it’s no surprise that much more material was composed and recorded at the time than made the final cut. Outtakes, alternates, and demos fill up three of the four CDs on this deluxe edition, the original LP occupying the other CD and the vinyl disc that comes with the package.

Of the 38 non-original-LP tracks, all but nine are previously unreleased, the others having previously appeared on various archival projects. That’s quite a boon for the CSNY fanatic, especially since the band had barely gotten together before they broke up. But while interesting, the extras reinforce how the ten songs chosen for the marketplace were the best and most appropriate of the lot, with just a few arguable exceptions.

Disc two is devoted to demos, and are almost more the work of contemporary folk artists than a rock band, especially as only one features Crosby, Stills, & Nash together (and none feature the whole quartet). Of course, most of the group had strong folk roots as well, giving you a glimpse of what they might have sounded like had they somehow never converted from folk to rock. Usually the songs left unused for Déja Vu would find a home on their solo releases; sometimes they’d actually previously been recorded as outtakes by their pre-CSNY groups, as Crosby’s “Triad” had by the Byrds and Nash’s “Horses Through a Rainstorm” (written with Terry Reid) had by the Hollies.

As for highlights, Nash’s “Right Between the Eyes” (which did make CSNY’s live Four Way Street double LP) would have made a less saccharine contribution than the two admittedly more commercial songs he wrote that made Déja Vu, “Our House” (heard here as a both a Nash solo performance and a somewhat lo-fi and sloppy Nash-Joni Mitchell duet) and “Teach Your Children.” Nash and Young duet fairly nicely on “Birds,” the only non-original-LP song on the whole box written by Neil. Lasting nearly seven minutes, Stills’s “She Can’t Handle It” has the kind of affecting yearning quality of other songs of his from the era like “4 + 20” (also heard in demo form) and “Questions.” Maybe it was considered a little too similar to those to get in the final running.

The eleven songs on disc three are full-band outtakes, all but one (another “Horses Through a Rainstorm”) previously unreleased. These alone prove Déja Vu easily could have been a double album, albeit a less consistently strong one than the single disc into which it was whittled down. Some of them would be among the more popular items from early solo releases by the gang, like Crosby’s “Laughing” (soon to be on If I Could Only Remember My Name) and Stills’s “Change Partners” (here in a form titled “Hold on Tight/Change Partners.”

If there’s such a thing as generic early CSNY, however, it sort of characterizes this batch. Strong harmonies and Stills’s confident multi-instrumental skills usually make for pleasant listening. But the tunes simply aren’t as strong as Déja Vu proper, even if they often rock out harder than some who pigeonhole CSNY as sorta-wimps acknowledge.

As befits a disc titled “alternates,” CD four has alternate versions (sometimes just alternate mixes or featuring alternate vocals) of every song from Déja Vu except “Country Girl” and “Everybody I Love You.” None are as good as the ones of the LP; alternates seldom are in these archival exercises. Still, there are moments that make your ears perk up, like some dirty lead guitar dueling in “Almost Cut My Hair,” and a “harmonica version” of “Helpless” (previously available on Young’s Archives Vol. 1) that, of course, includes harmonica.