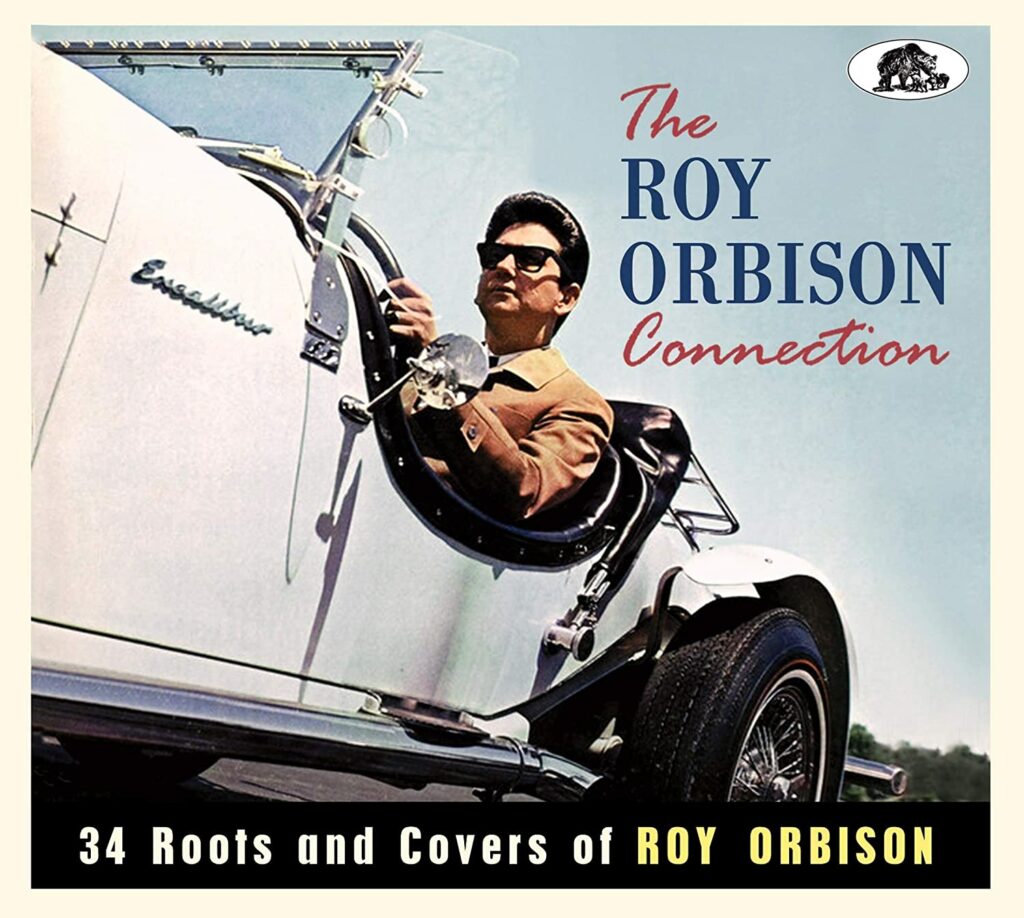

Once in a while a reissue comes out that isn’t good enough to make a best-of list, but is kind of interesting, if only for the strangeness of its concept. One such item from 2021 is The Roy Orbison Connection: 34 Roots and Covers of Roy Orbison, on Bear Family. All of these tracks were either covers of songs Orbison did, or versions of songs that Roy covered. Bear Family’s done similar collections for Elvis Presley and Bill Haley.

None of these postdate the 1960s, and include a wealth of big names, among them Bobby Fuller, Bobby Vinton, Gene Pitney, the Everly Brothers, Wanda Jackson, Bruce Channel, Waylon Jennings, Jerry Lee Lewis, Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash, and Del Shannon. If you’re wondering how they could come up with 34 tracks, there must have been way more than 34 that would qualify.

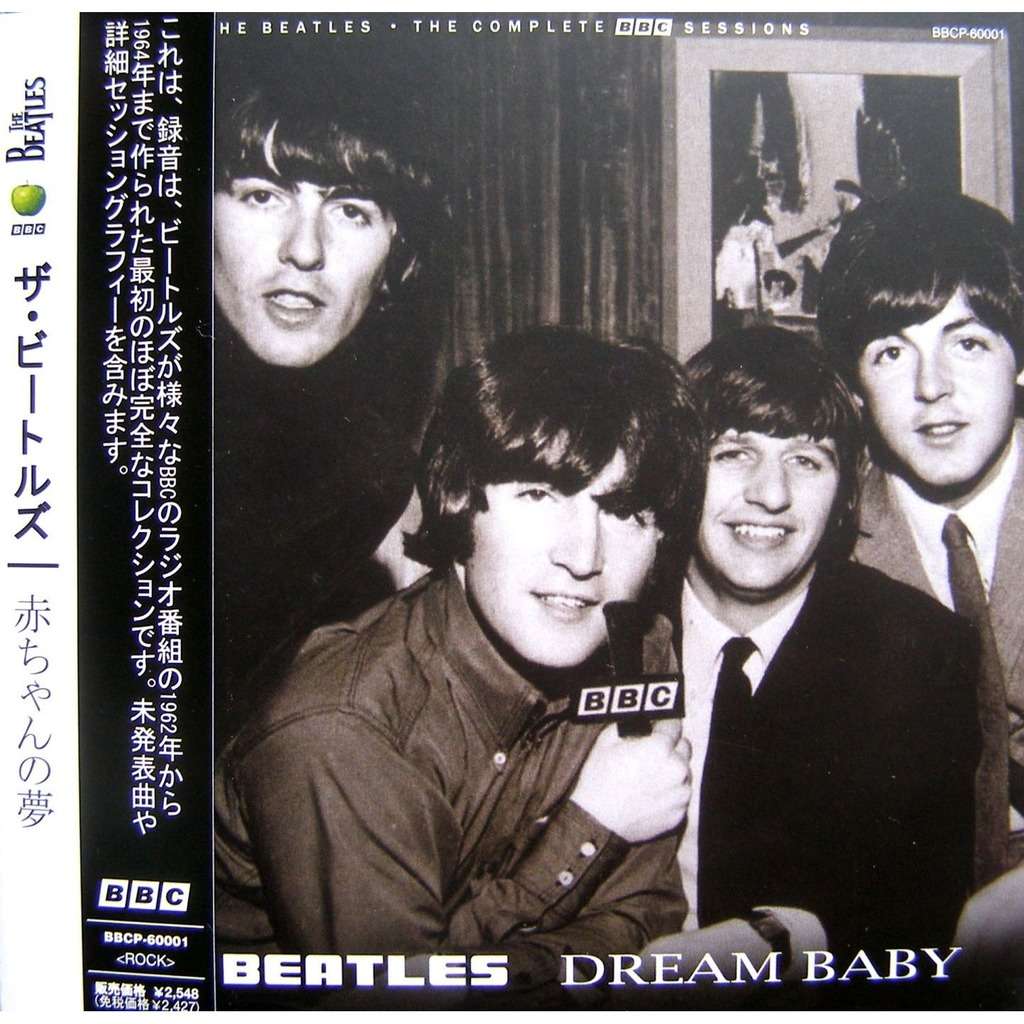

The British group the Four Pennies, for instance, did “Running Scared” in the 1964 film Swinging UK, and it’s not here (nor is it especially worth tracking down). The Beatles did a far better and more historically significant cover of “Dream Baby” on their first BBC radio appearance (when Pete Best was still drummer) on March 7, 1962. It’s often been bootlegged, but never been officially issued, most likely because of its taped by a cheap recorder next to a radio speaker fidelity.

There are a bunch of no-names, or at least ones that will be unfamiliar if you’re not a huge collector. Vernon Taylor, Don Duke, Mike Redway, and the Schneider Sisters, anyone? And there are names that are primarily familiar to rockabilly aficionados, like Narvel Felts, Sid King, and Janis Martin. Ken Cook recorded Orbison’s composition “Problem Child” for Sun Records in 1956, but it didn’t come out until 1976. Joe Melson won’t be a name recognized by many, but he had an important role in Orbison’s career as a co-writer (with Roy) of much of Orbison’s material in Roy’s prime in the first half of the 1960s.

These kind of collections are seldom great listens all the way through, let alone as good as the most familiar versions. That’s even true of the very best artists, like the Beatles, or songwriters, like Carole King and Gerry Goffin. A lot of these cuts are more curiosities than quality efforts, or even too interesting.

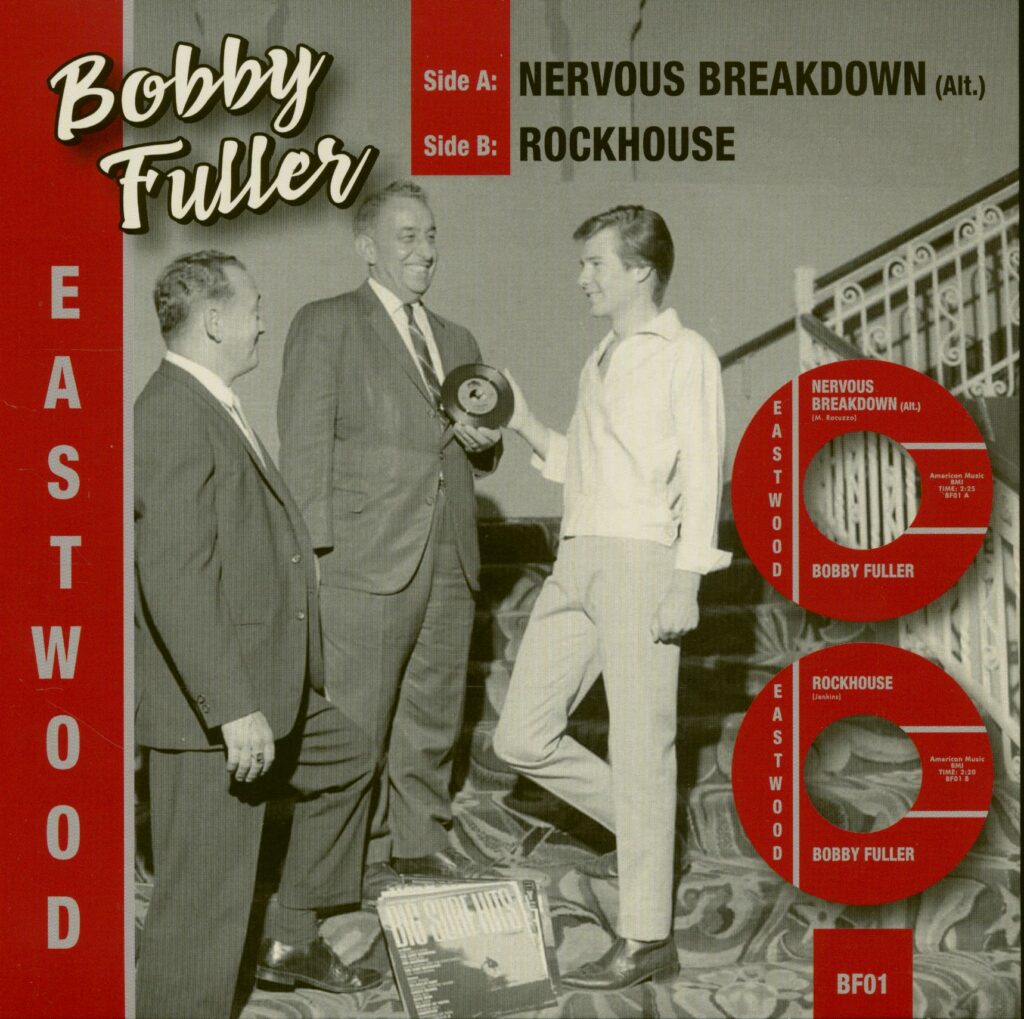

That applies to The Roy Orbison Connection, where there are few cuts that stand out as particularly worthwhile, though few are subpar. Often they’re rather unimaginatively close to Orbison’s version, and unsurprisingly not as good. This could be said of Del Shannon’s “Oh, Pretty Woman,” Waylon Jennings’s “The Crowd,” or Bruce Channel’s “Dream Baby.” Bobby Fuller’s “Rock House” is pretty good, but not notably different or leagues above Orbison’s rendition. Johnny Cash’s “You’re My Baby” (which Roy could cover) is just weird, Cash almost sounding like he’s forcing himself to do rockabilly, especially on one chorus where he emits a bizarre yelp.

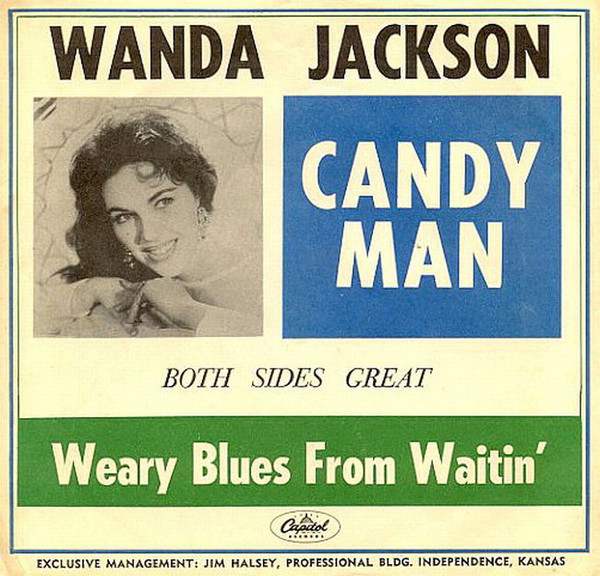

Amidst the generally run-of-the-mill, or sometimes worse, variations are a few good performances. Wanda Jackson sounds sexy (and rather like Brenda Lee) on “Candy Man,” though Roy and for that matter Fred Neil (who co-wrote the song with Beverly Ross) did it better. Jerry Lee Lewis’s “Down the Line” is solid and better than Orbison’s original; he did a good “Mean Woman Blues” in 1957 too, though Roy both did it better and made it his own when he had a Top Five hit with the song in 1963.

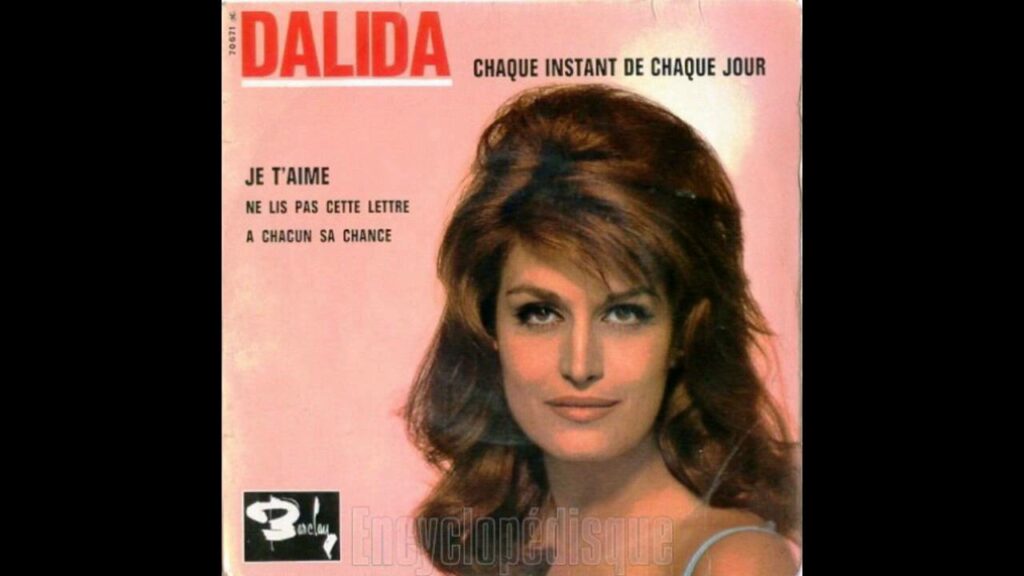

Dalida’s French-language treatment of “It’s Over” stands out in this company just because it’s different than anything else, both in the language and the European orchestrated arrangement. You don’t have to be fluent in French to catch that its retitling as “Je T’Aime” (“I love you”) isn’t an exact translation.

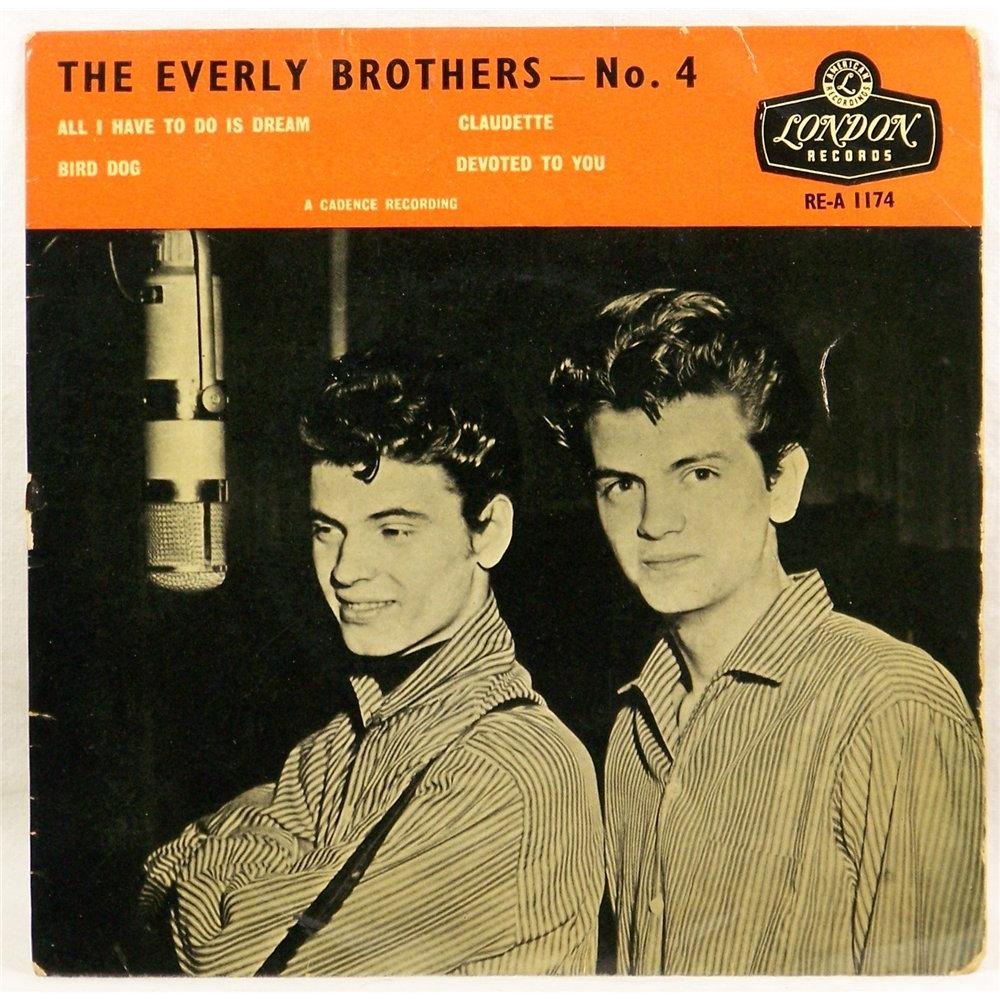

The clear winners as Orbison’s most important interpreters are the Everly Brothers. Before Roy had a big hit of his own, they took a rousing run through his composition “Claudette” into the Top Thirty in 1958 (as the B-side of the chart-topping “All I Have to Do Is Dream”). It’s considerably superior to the version Orbison later did on his 1965 LP There Is Only One Roy Orbison.

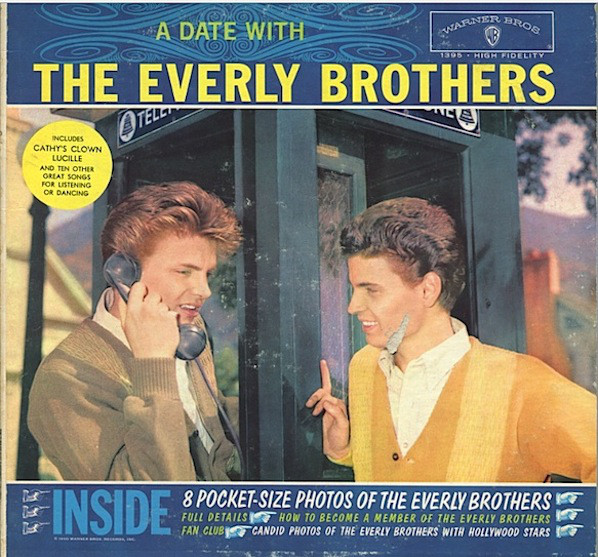

The Everlys also did a superb interpretation of Boudleaux Bryant’s “Love Hurts” on their 1960 album A Date With the Everly Brothers, itself one of the best-pre Beatles non-compilation rock LPs. They used a pretty straightforward mild rock arrangement with a gingerly swelling electric guitar. Orbison put the song on the B-side of “Running Scared” and opted for a much more orchestrated approach that could have been a big hit as an A-side. It’s close to a tie as to which track is better; I guess I’d go with the Everly Brothers, though they’re so markedly different that each can be appreciated as a highly worthwhile production.

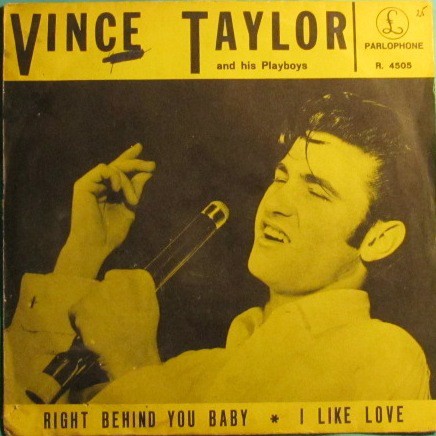

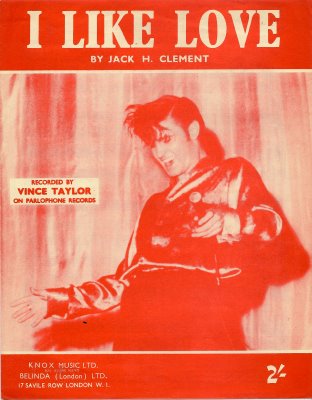

There’s one selection on The Roy Orbison Connection that stands out as a recording that’s both obscure and better than Orbison’s original. “I Like Love,” written by Sun producer Jack Clement, was Roy’s last single for the label in 1957. An average, even generic Sun rockabilly number, it made no commercial impact, but was picked up across the Atlantic by Vince Taylor, one of Britain’s few notable pre-Beatles rock singers. Actually he couldn’t sing too well, but made it for it with oodles of enthusiastic attitude and some good studio backup musicians. In that respect he had much in common with another of the UK’s few pre-Beatles rockers of consequence, Screaming Lord Sutch.

Taylor’s most remembered for “Brand New Cadillac,” covered much later by the Clash, and for supplying part of the inspiration for David Bowie’s Ziggy character. He wasn’t remotely close to Orbison in either the quality of his music or his historical significance. But his 1958 single “I Like Love” has frenetic energy and is decisively better than Orbison’s rather unmemorable prototype.

There’s some more historical significance to Taylor’s “I Like Love.” It has some of the best guitar on any 1950s British rock’n’roll single, and indeed some of the only good guitar in 1950s rock, especially in the manic if brief solos. That guitarist was Tony Sheridan, who’d go on to fame, of sorts, as a mentor in Hamburg in the early 1960s to the Beatles, who’d back him on some recordings in Germany before they started their own recording career. Now there’s a Roy Orbison connection that echoed way beyond the rather specialized niche of who did Orbison songs, or whose songs Orbison did.