Paul McCartney: The Lyrics is a very good book. It’s much better than I expected, since most books of rock lyrics just print the lyrics with some illustrations of no great consequence. This two-volume, expensive-but-worth-it production has a lot of text featuring detailed recollections from McCartney himself about his songs. It also has a lot of illustrations, but they’re pretty interesting and often rare or previously unpublished. A full reprint of my review of the book from my previous post of my favorite rock books of 2021 is at the end of this post.

This post, however, is not another review of Paul McCartney: The Lyrics. It’s sort of a fact-check on some of its text. It’s a good book, but it’s not perfect.

To quote from my review: “There are a few, if not many, factual mistakes that I’m surprised made it through the editing process…There are many, many Beatles fans besides myself who could have spotted such errors, and the essence and primary points of the stories could have been retained if they’d been fixed. Was it unimportant to McCartney and the publisher to make the relatively modest effort necessary to catch those?”

It doesn’t surprise me that Paul misremembers some incidents, and particularly gets some order of what happened when wrong. Some of these things happened fifty to sixty years ago. What does surprise me is that the publisher—a big one, with a very prestigious project—apparently didn’t care enough to do the kind of fact-checking that might be considered routine if this was a book on a major political figure or movement, rather than a mere celebrity musician who did more to change the world than most politicians.

So no, they didn’t ask me or, it seems, others who could have caught mistakes to go over the text. Not that I’m so special; there are probably thousands of fans who could have done so, and will while they’re reading the book. But here are ones I caught, if anyone’s interested in treating these as sort of corrective footnotes.

On page 64: Remembering recording “Can’t Buy Me Love” in Paris in January 1964, Paul muses, “The irony here is that just before Paris, we’d been in Florida where, if not love, money certainly could buy you a lot of what you wanted.”

To those not steeped in the history of Beatles recording sessions, it might seem like the mistake is that the hit was recorded in Paris, not London, where they cut almost all of their records. However, “Can’t Buy Me Love” was indeed recorded in Paris on January 29, 1964, while the Beatles were playing shows in the city for almost three weeks.

The error is the first of several chronological ones in the book that might seem trivial to plenty of people, but are certainly mistakes. The Beatles hadn’t been in Florida before this session. In fact, only George Harrison had been to the United States, and he didn’t go to Florida during his trip there (mostly to see his sister in the Midwest) in late 1963.

The Beatles did go to Miami in mid-February 1964, only a couple weeks after recording “Can’t Buy Me Love,” for a short vacation after their famous initial American appearances on the Ed Sullivan Show and concerts in Washington, DC and New York’s Carnegie Hall. They also performed the last of their three Sullivan spots this month in Miami.

It’s odd that McCartney switches the order of events that did happen very close to each other, but where one (their first US visit) was much more famous and important to the group’s career than the other (their visit to Paris). There might be literally millions of Beatles fans who’d spot this switcheroo, which just shows that followers of celebrities often know more about such details than the stars who actually experienced them.

On page 91: “My favorite electric guitar is my Epiphone Casino. I went into the guitar shop in Charing Cross Road in London and said to the guy, ‘Have you got a guitar that will feedback, because I’m loving what Jimi Hendrix is doing.’ I’m a big admirer of Jimi. I was so lucky to see him at one of his early gigs in London and it was just like the sky had burst…

“The guitar shop staff said, ‘This is probably the one that will feedback best, because it has a hollow body and they produce more volume than a solid body guitar.’ So I took it to the studio, and it had a Bigsby vibrato arm on it, so you could play with the feedback and control it, and it was perfect for that. It was a really good little guitar, a hot little guitar. So that became my favorite electric guitar, and I used it on the intro riff to ‘Paperback Writer’ and the solo in George’s song ‘Taxman,’ as well as quite a number of other pieces through the years. I still play it today. That Epiphone Casino has been a constant companion throughout my life.”

Cool, but McCartney wouldn’t have seen Hendrix until late September 1966 at the earliest, which is when Jimi moved from New York to London. Hendrix did some gigs right away before the Experience formed, but my guess is Paul didn’t see him until at least a little later than September. “Paperback Writer,” however, was recorded quite a bit earlier, on April 13 and 14, 1966, during the Revolver sessions. “Taxman” was recorded about a week later. Either he wouldn’t have seen (and almost certainly not heard of) Hendrix before he used that Epiphone Casino on those songs, or maybe there were later recordings where he used it with a Hendrix feel in mind.

Although it’s not a mistake, it’s interesting that Paul refers to using this “on the intro riff to ‘Paperback Writer.’” That seems to mean that McCartney, and not George Harrison, plays lead guitar on at least part of the song. (In late 2022, the notes to the superdeluxe edition of Revolver clarified that Paul “used an Epiphone Casino hollow-body electric guitar for the propulsive riffs of ‘Paperback Writer.'” Harrison, according to the notes, “doubled the guitar riffs that follow each of the choruses.”)

According to Andy Babiuk’s quite thorough and authoritative Beatles Gear (as well as the Revolver superdeluxe liner notes), McCartney actually bought an Epiphone Casino guitar around December 1964, almost two years before Hendrix became known in London. Paul’s account from a July 1990 issue of Guitar Player might well be the more accurate one of how he was inspired to get the instrument, noting that British blues-rock great John Mayall “used to play me a lot of records late at night. He was a kind of DJ type guy. You’d go back to his place and he’d sit you down, give you a drink, and say just check this out. He’d go over to his deck, and for hours he’d blast you with B.B. King, Eric Clapton…he was sort of showing me where all of Eric’s stuff was from. He gave me a little evening’s education in that. I was turned on after that, and I went and bought an Epiphone.”

Page 105: “I’d say to the other guys, ‘Let’s use a library sound of an audience laughing when “the one and only Billy Shears” is introduced to sing “With a Little Help from My Friends”’.” This is fairly minor, but the sound of an audience laughing is heard after the first verse of the title track from Sgt. Pepper, much earlier in the song. Audience noise is heard at various points throughout the “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” track, but after the line referring to Billy Shears near the end, it’s more general chatter and screaming, not laughter. Of course to be picky, maybe Paul originally suggested laughter here, but they ended up using different audience noise instead.

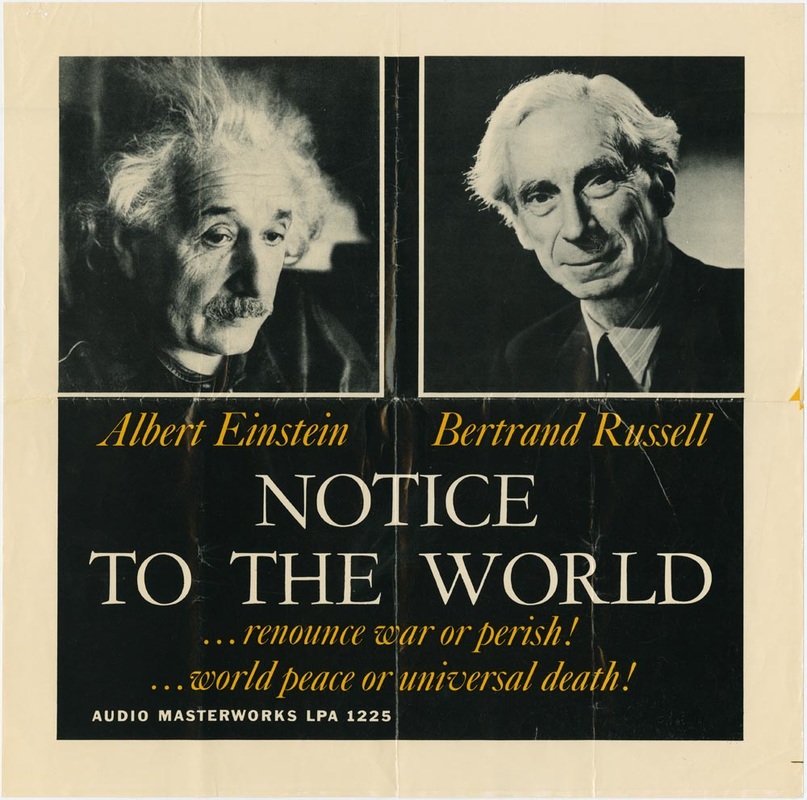

p. 131: Paul places his meeting with Bertrand Russell, the famous philosopher, author, and pacifist, in “I think, around, 1964.” This isn’t entirely a mistake as McCartney qualifies the date with an estimate, but the exact date of the meeting—meetings, actually—were June 18, 1966 and June 20, 1966, according to Russell’s wife’s appointment book.

It could seem unfair to pick on something like this, but this does matter to some historians, and not just music historians. I was asked by someone teaching a course on anti-war activism for details about the meeting, and these two years would have made a significant difference in accurately portraying the situation. American involvement in the Vietnam War, which McCartney has credited Russell with greatly increasing his awareness of, was considerably heavier and far more in the news in 1966 than 1964. Not to fault Paul for whenever he became more fully aware of the conflict, but 1964 would have been much earlier for someone of his age to have been clued in on the negative aspects of the war, and for McCartney to discuss this with Lennon, as he’s on several occasions remembered doing shortly afterward in the studio. That would have been as the Revolver sessions were wrapping up, and fit in the timeline of how the Beatles criticized US involvement in the war to the American press during their final tour in summer 1966, a couple months or so after Paul met Russell.

p. 179: A caption states “For No One” “was written in the Austrian Alps during the filming of Help! March 1965.” While this isn’t demonstrably untrue, the Beatles hadn’t even finished recording the Help! album at that point. It seems very unlikely they would have waited until Revolver to record it in 1966, not putting it on either Help! or the album they recorded in late 1965 between the two, Rubber Soul. Maybe Paul started writing it in March 1965 and it took a long time to complete, but that’s not what the caption or any other source states.

He seems to have mixed up his skiing trips, as according to Barry Miles’s 1997 book Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now, written with extensive input from McCartney, the song “was written in March 1966 when Paul and Jane were on their skiing holiday in Klosters, Switzerland.” In the same book McCartney confirms, “It was very nice and I remember writing ‘For No One’ there.”

Page 185: Discussing “From Me to You,” according to Paul, “We were on tour with Roy Orbison at the time we wrote this. We were all on the same tour bus, and it would stop somewhere so that people could go for a cup of tea and a meal, and John and I would have a cup of tea and then go back to the bus and write something. It was a special image to me, at 21, to be walking down the aisle of the bus and there on the back seat of the bus is Roy Orbison, in black with his dark glasses, working on his guitar, writing ‘Pretty Woman.’ There was a camaraderie, and we were inspiring each other, which is always a lovely thing. He played the music for us, and we said, ‘That’s a good one, Roy. Great.’ And then we’d say, ‘Well, listen to this one,’ and we’d play him ‘From Me to You.’ That was kind of a historic moment, as it turned out.”

Great, but the tour with Orbison took place in the UK between May 18 and June 9 of 1963. The Beatles recorded “From Me to You” on March 5, 1963, more than two months before the start of the tour. It’s back to Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now for a firmer date, as Barry Miles writes the song was composed “on 28 February 1963 in the tour bus traveling from York to Shrewsbury on the Helen Shapiro tour,” the Beatles’ first tour of the UK.

Certainly it’s quite possible Lennon and McCartney played Orbison songs they were writing during that subsequent tour. They could well have played him “From Me to You,” considering it was not only already written and recorded, but also that it was #1 on the British charts the whole tour, and the Beatles were playing it in concert every night. When Paul discusses “From Me to You” in Many Years from Now, he adds, “After that [italics mine], on another tour bus with Roy Orbison, we saw Roy sitting in the back of the bus, writing ‘Pretty Woman.’” McCartney seems to have conflated writing “From Me to You” on one tour and seeing Orbison writing “Pretty Woman” on another tour a few months later.

Orbison, by the way, didn’t record “Oh, Pretty Woman” until August 1, 1964. It seems unlikely he would have sat on such a strong number for more than a year, though of course that’s impossible to prove, and maybe he was just starting to write it and it took a long time to complete.

p. 389: Here’s a mistake for which McCartney probably can’t be held accountable. A caption to a picture of Paul with Wilfrid Brambell, who played his grandfather in A Hard Day’s Night, reads “With Wilfred Bramble.” The first sentence of the text for this entry (for the song “Junk”) spells Brambell’s first and last name right. Did anyone proofread that caption?

p. 639: Paul recalls the genesis of the title track for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and indeed the whole Sgt. Pepper concept, as follows: “I’d gone to the US to see Jane Asher, who was touring in a Shakespeare production and was in Denver. So I flew out to Denver to stay with her for a couple of days and take a little break. On the way back, I was with our roadie Mal Evans, and on the plane he said, ‘Will you pass the salt and pepper?’ I misheard him and said, ‘What? Sergeant Pepper?’”

McCartney visited Asher on her 21st birthday, which was in early April 1967. The last session for the Sgt. Pepper album was completed on April 3, although some remixing was done later that month. The first session for the Sgt. Pepper title track had taken place on February 1, by which time the song had certainly been written, and the concept probably starting to take hold. Other reliable sources have reported that Paul started to come up with the Magical Mystery Tour title song and film concept during the Denver trip, and maybe he mixed up the chronology of the conception of these two projects.

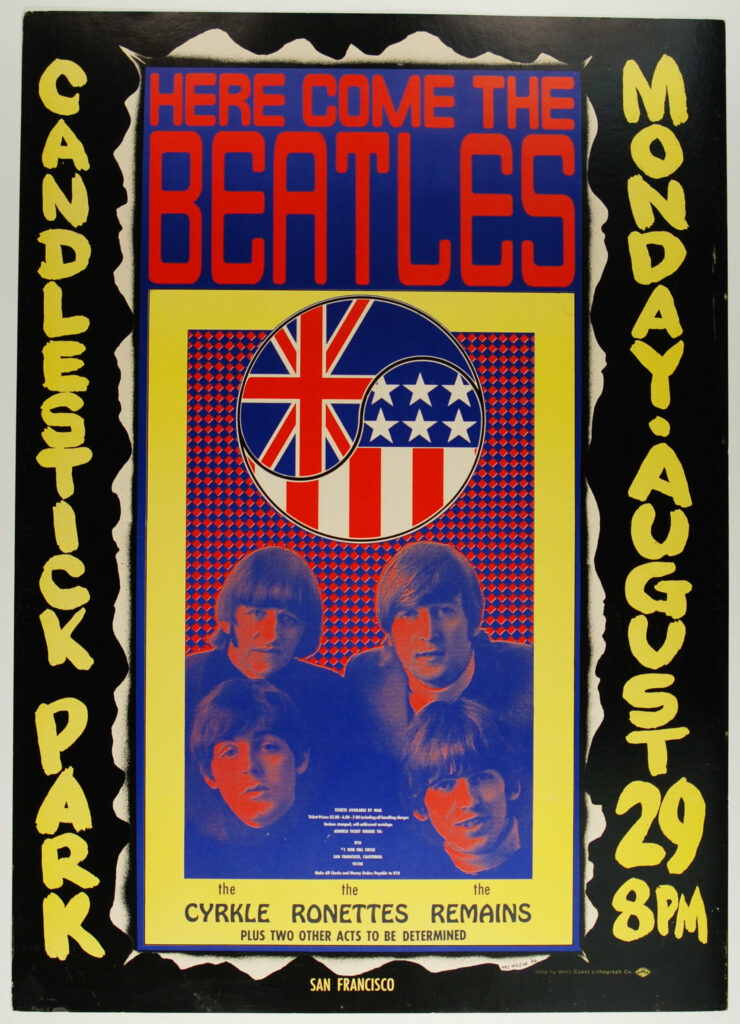

p. 639: Also in the entry for “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” setting the context for how the album in part evolved from their retreat from live performances, Paul notes: “We had recently played Candlestick Park. That was a show where we couldn’t even hear ourselves; it was raining, we were nearly electrocuted and when we got off stage we were chucked into the back of a stainless steel minitruck. The minitruck was empty, and we were sliding round in it, and we all thought, ‘Fuck, that’s enough.'”

This was actually the Beatles’ last official concert, in San Francisco on August 29, 1966. It can be pretty chilly and foggy in San Francisco in the summer. Paul seems to notice this in a much-bootlegged tape of most of the show, announcing before the “Long Tall Sally” finale, “We’d like to say that it’s been wonderful being here in this wonderful sea air.” He also remarks “it’s a bit chilly” after “Yesterday.” As a resident of the San Francisco Bay Area for nearly forty years, I can testify that it’s not rare for the summer fog to be so heavy it can almost seem like it’s drizzling.

But I can also testify that it rarely actually rains in San Francisco in the summer. And it wasn’t raining at Candlestick Park during this concert. I’m a bit hesitant to call this an outright mistake if Paul and the Beatles felt like it was raining. But no accounts of which I’m aware, and there are quite a few, of the concert report that the Beatles were in danger of being electrocuted. There are, for instance, quite a few in Ticket to Ride: The Extraordinary Diary of the Beatles’ Last Tour, by Barry Tashian, leader of the fine Boston group the Remains, who were a support act on the Candlestick bill. These include Tashian’s own memories, eyewitness reports from fans, and reprints of 1966 reviews of the concert in the San Francisco Examiner and TeenSet. None of them mention rain (although Tashian does recall that “on stage, a wild sea wind was blowing in every direction”), let alone danger of electrocution.

I believe Paul was actually thinking of a concert from just a few days earlier in Cincinnati. The Beatles were scheduled to play at Crosley Field on August 20, 1966, but the concert was canceled two hours after its scheduled 8:30 start time due to rain. The Beatles indeed feared they’d be electrocuted if they went on, George Harrison remembering in The Beatles Anthology, “It was so wet that we couldn’t play. They’d brought in the electricity, but the stage was soaking and we could have been electrocuted, so we canceled—the only gig we ever missed.”

In the 1972 book Apple to the Core attorney Nat Weiss, who worked on the Beatles’ business affairs in the US, remembered that McCartney in particular was upset by the incident: “We’d just been through a very bad experience in Cincinnati. The promoter had been trying to save himself a few cents by not putting a roof over the stage. It started to rain and the Beatles couldn’t go on because they would have been in danger of electrocution. They had to turn away 35,000 screaming kids, who were all given passes for a concert the next day. The strain had been obviously too much for Paul. When I got back to the hotel, Paul was already there. He was throwing up with all this tension.” (The Beatles did play in Crosley Field the following day, when the weather was clear.)

That would explain how that incident would be specifically cited when McCartney remembered how and why the Beatles decided to stop touring. But it seems very doubtful the near-electrocution he’s referring to took place in Candlestick Park. For that matter, the sliding around in a stainless steel minitruck might well have happened in Cincinnati rather than San Francisco, since Paul places this mishap after a show where “it rained quite heavily” in The Beatles Anthology.

It’s a little odd, though it’s not a mistake, that Paul doesn’t note the Candlestick Park concert was their final official gig, as it’s been cited as such in many, many historical accounts. He certainly must know it was, as he made a point of doing the last official concert held in Candlestick Park in 2014 before it was demolished, as a sort of homage to the Beatles having played their final show there.

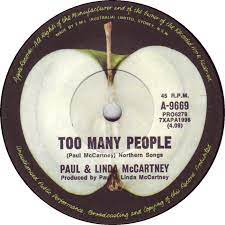

p. 721: In the entry for “Too Many People,” the song that John Lennon interpreted as a jab at him and spurred his famous response “How Do You Sleep?,” Paul gives this account of one of the factors leading to the Beatles’ breakup and subsequent ill feelings between the pair: “The whole story in a nutshell is that we were having a meeting in 1969, and John showed up and said he’d met this guy Allen Klein, who had promised Yoko an exhibition in Syracuse, and then matter-of-factly John told us he was leaving the band. That’s basically how it happened.”

Not exactly, or at the least this drastically condenses the timeline of what occurred. As the recent Get Back documentary makes clear, John and Yoko had their first significant meeting with Klein in late January of 1969, near the end of the January 1969 recording sessions and filming that eventually produced the Let It Be LP and film. (The date of both January 26 and January 27 have been given for the meeting, though judging from the film and the companion book of dialogue from the sessions, January 27 seems more likely.) According to the Get Back documentary, the Beatles as a group had their first meeting with Klein on January 28, very shortly afterward.

It’s not too important whether or not the Beatles managed to first have a group meeting without Klein where “John showed up and said he’d met this guy Allen Klein.” Certainly, however, McCartney knew about Lennon’s interest in having Klein as the Beatles’ manager by January 28 at the latest. Certainly John wouldn’t have “told us he was leaving the band” at that meeting. He played in the Beatles’ last concert on the roof of Apple a couple days later, for crying out loud.

The meeting at which John said he was leaving the band is usually reported as having taken place in September 1969, not long after he’d done a concert in Toronto without the Beatles (on September 13) as part of the Plastic Ono Band. That’s almost eight months after the group meeting with Klein in late January, and they’d recorded all of Abbey Road in the interim. For what it’s worth, Lennon didn’t officially leave the band after that September announcement, at least publicly. The Beatles are usually considered to have split on April 10, 1970, when Paul’s intention to leave became public.

Also for what it’s worth, Yoko’s Syracuse exhibition didn’t take place until October 1971. It seems very improbable that Klein would have promised Yoko a Syracuse exhibition at their first or one of their first meetings, which took place back in late January 1969. Paul’s account makes it look like the first time John told him and the Beatles about Klein, he told them Klein had promised Yoko the exhibition.

Most of the mistakes noted in this post are apparent jumbles of chronology, understandable to a degree of events that happened more than fifty years ago, and not ones that are going to seriously disturb most readers or Beatles fans. This one, however, might be the most egregious error, significantly distorting the roles Klein and Lennon played in the Beatles’ breakup.

p. 847: Reinforcing the inaccurate chronology of the previous item, in the entry for “You Never Give Me Your Money,” Paul reports that “it was early 1969, and the Beatles were already beginning to break up. John had said he was leaving, and Allen Klein told us not to tell anyone, as he was in the middle of doing deals with Capitol Records. So, for a few months we had to keep mum. We were living a lie, knowing that John had left the group.”

Almost all of this is true, pretty much, though the split wouldn’t be final until spring 1970. Except that this wasn’t early 1969. It was September 1969 when John announced he was leaving, and Allen Klein convinced him (and, perhaps, the rest of the Beatles) not to tell anyone, since he was making a new deal for the group. Paul’s off by about half a year, and that’s not a trivial inaccuracy, since the Beatles would record Abbey Road during that time.

Do about a dozen errors (and maybe I missed some others might have caught) over the course of 875 or so pages make for a substandard volume? No, of course not, though I think they’re noteworthy enough to be cited in case no one else does. It doesn’t seriously impair the overall high value of the book, my full review following below, as promised.

Paul McCartney: The Lyrics, by Paul McCartney, edited with an introduction by Paul Muldoon (Liveright). The most well known book, perhaps by far, on this list, as it was a #1 New York Times best-seller. Just because it was commercially successful, however, doesn’t mean it isn’t good—kind of like the Beatles themselves. Crucially, it’s not just a book that prints the lyrics with some illustrations, though the lyrics of 154 of the songs he wrote or co-wrote are here, and there are lots of graphics. There’s also a lot of text in which McCartney discusses composing the specific tunes, often throwing in a lot of observations about influences, inspirational incidents and people and his life, and life in general. Most of the really well known songs he wrote (with the odd exception like “Hello Goodbye” and “Magical Mystery Tour”) are included, and there are some really obscure ones from both the Beatles days and his solo career, even reaching back to a late-‘50s number (“Tell Me Who He Is”) that was never released, and for which McCartney doesn’t remember the tune.

While some of these stories have been told a fair amount (and a few are even repeated with variations in the text), the commentary’s almost unflaggingly absorbing and entertaining, both for the information and the lively, witty way McCartney tells it. While I’m not overall interested in much of his post-early-‘70s solo career, even the notes on those are usually worth reading, as they usually have noteworthy stories and perspectives not specifically related to the songs themselves—quite a few of which from the previous decades, I admit, I’m not familiar with. Here’s one of the better examples of his wisdom, in discussing a character in “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window”—“She found a ladder lying outside my house in London. As far as I recall, she stole a picture of my cotton salesman dad. Or robbed me of it. But I got the song in return.”

This doesn’t nab the #1 spot on my list since it does spotlight a good number of songs from a period of his career that doesn’t interest me (even if, as previously noted, the stories accompanying those usually do). A few (not many) notable Beatles songs in which he was the main writer—“I’ve Just Seen a Face” and “I’m Looking Through You” are a few others—are missing. And there are a few, if not many, factual mistakes that I’m surprised made it through the editing process. For instance, Paul remembers getting the title for “Sgt. Pepper” from a remark Mal Evans made on a plane ride back from visiting Jane Asher on her 21st birthday in Denver, although that was in early April 1967, and the song “Sgt. Pepper” had largely been recorded on February 1. There are many, many Beatles fans besides myself who could have spotted such errors, and the essence and primary points of the stories could have been retained if they’d been fixed. Was it unimportant to McCartney and the publisher to make the relatively modest effort necessary to catch those?

To get back to the book’s substantial pluses, the photos and illustrations are really good, and sometimes rare and unseen (though the absence of captions on some is frustrating). Besides pictures dating back to his childhood, there are plenty of McCartney’s handwritten lyrics, drawings, and letters. Most interesting to me of all were a few very early Beatles setlists, from around the late 1950s and early 1960s, listing some songs they haven’t been documenting as performing. And yes, this is an expensive (though not massively so) book, but it’s worth owning.