I’ll be teaching a course on Pink Floyd for the first time in late August, and spent a lot of time preparing the material over the last few weeks. As I got my class together, I’ve heard and seen a lot more Pink Floyd than I have for a while.

There’s been a lot written about Pink Floyd. Still, there are a few aspects of their work that aren’t discussed much. Like I did when I offered a Doors course a few years ago, I’m going over about a half dozen of them with this blogpost.

1. The musical demise of Syd Barrett. As much as there’s been about Pink Floyd the group, there’s much that’s been written and speculated just about Syd Barrett, although he made just one album and a few singles with them as their original leader. It’s widely known that he made some abortive attempts at doing some recording in 1974, about four years after his second and last solo LP. Some material from those sessions has long been bootlegged.

I didn’t realize, however, until viewing the 2012 documentary Pink Floyd: The Story of Wish You Were Here that a few scraps are heard in that film, marking the only officially available extracts. If Barrett’s solo albums were something like, to paraphrase Pink Floyd biographer Nicholas Schaffner, like much of the method had gone out of his madness, the 1974 sessions are like hearing a brain that’s almost closed down. There’s some personality fighting to get out of these instrumental bits and pieces, but it’s almost like it’s seeping out from some of the few empty bricks in a wall, to use a description Roger Waters might appreciate.

One wonders if the sessions were a last-ditch attempt to get Barrett involved in something positive and creative again, a last-ditch attempt to exploit whatever commercial value might be left in a recording by the original Pink Floyd leader in the wake of The Dark Side of the Moon, or something in between. Whatever the case, it couldn’t have been a pleasant exercise for anyone involved.

Considering Pink Floyd’s post-Barrett success—not just with Dark Side of the Moon, but really starting right away with the UK Top Ten success of their second (and first post-Barrett, for the most part) LP, A Saucerful of Secrets—one wonders whether he would have continued to dominate the group as much as he did on The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, even had he remained mentally healthy. Even before Syd’s departure, Waters and Rick Wright were writing some LP tracks and B-sides that, if not among the best of the group’s work, were certainly respectable. One can only speculate that perhaps Waters and Wright would have written a significant and growing share of the songs as time went on, even if Barrett continued to pen the majority of the compositions. It’s a what-if that will never be known.

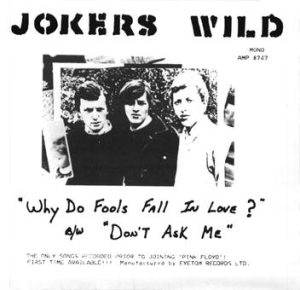

2. David Gilmour before Pink Floyd. Unfortunately there’s little recorded evidence of David Gilmour’s music before he joined Pink Floyd around the end of 1967, and what’s circulated isn’t very impressive. He was the group Joker’s Wild, and five unreleased tracks they’ve recorded have been heard. They’re all cover versions; there’s not even much guitar on most of them; and if Gilmour’s singing, it’s not easily detectable. It’s the kind of thing a semi-pro band might give to prospective promoters as evidence that they could replicate some hits and songs by famous acts live.

It’s not at all like Pink Floyd either, and in fact doesn’t have much personality whatsoever. There are faithful covers of “Why Do Fools Fall in Love,” but actually as done by the Beach Boys, not the original hit arrangement by Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers; the Four Seasons’ “Walk Like a Man” and “Big Girls Don’t Cry”; Manfred Mann’s bluesy “Don’t Ask Me What I Say,” written by their original singer Paul Jones, which at least was a pretty deep LP track that took some digging to find; and Chuck Berry’s “Beautiful Delilah,” not one of his more renowned numbers, though the Kinks covered it their first album and the Rolling Stones did it on the BBC. On “Beautiful Delilah,” Gilmour (presuming he’s the lead guitarist) finally peels off a solo, but it’s a routine competent one of the sort heard on tons of recordings by generic mid-‘60s British R&B/rock bands.

It’s sometimes speculated Gilmour got into Pink Floyd mostly because he was a friend of the group with (like Barrett and Waters) roots in Cambridge, and the Joker’s Wild demos would lend ammunition to that theory. I would think, however, that Gilmour must have improved a lot between the time of these demos and joining Pink Floyd, and/or that the demos simply don’t represent his talents well, since he quickly proved himself a good and distinctive guitarist, and a significantly talented singer and songwriter, after replacing Barrett. He might have been told “play like Syd Barrett” when he first joined the Floyd (augmenting the Barrett lineup for just a few weeks before Syd was gone for good), but he was sounding like himself soon enough. And at least some of that must have been cultivated before 1968.

Update: As seen in the comments section, reader Anthony Harland kindly just let me know that “Dave Gilmour’s early recordings also include singing on the soundtrack to a Brigitte Bardot film A Couer Joie. Michel Magne, the well known French composer and founder of the Chateau recording studio (Elton John’s “Honky Chateau”), wrote the music and wanted an English singer. Gilmour was in Paris at the time (1967) and got the job,” singing the tracks “Do You Want to Marry Me” and “I Must Tell You Why.’ While these too have little similarity to what Pink Floyd did after Gilmour joined, they’re fair period flower-pop-rock; “Do You Want to Marry Me” is the better of the pair. They’re better than the Joker’s Wild tracks, though likewise not remarkable.

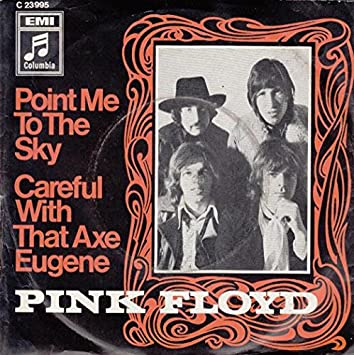

3. Musical “voices” in Pink Floyd. Pink Floyd don’t have a reputation as a particularly exciting live act, or at least one that projected a lot of personality onstage. Fortunately there’s a surprising amount of footage of the group from 1967-1973, much of it on the box set The Early Years 1965 to 1972. They were a little more animated onstage than legend sometimes has it, and not just in the early Syd Barrett/psychedelic days. Certainly the most animated member was Roger Waters, especially in the clips (there are several) of “Careful With That Axe, Eugene,” where he screams and gesticulates with genuine menace.

As a launching point for a general observation, Pink Floyd, and usually Waters, used non-musical mouth voices more frequently and with more imagination than is usually acknowledged in literature about the band. These actually date back to the Syd Barrett era, and weren’t only done by Waters. On Piper at the Gates of Dawn, “Pow R. Toc. H” is almost hard to classify as an instrumental, despite the absence of words, since it’s full of vocal noises, almost like they’re communicating without language in the jungle. The 1967 clip of them doing an unfortunately very brief extract on the BBC has Barrett making the vocal percussive noises at the start. On most of the studio track, other effects are featured that almost sound like demonic birdcalls. And then there are the unforgettable interjections, best transcribed as “doy doy,” that intimate madness as much as anything Barrett was involved with.

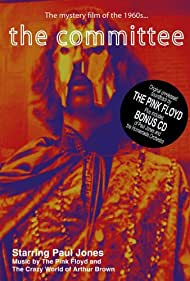

4. Pink Floyd soundtracks—the movies. Pink Floyd had some of their music on soundtracks almost from the time they started. An early, hyper-fast version of “Interstellar Overdrive” from late 1966 was used as the soundtrack to Anthony Stern’s highly experimental, psychedelic fifteen-minute short “San Francisco” (the music came out on a limited edition Record Store Day release a few years ago). Only a little less obscurely, some instrumental pieces are heard in the hour-long 1968 British movie The Committee. They’re on the Early Years 1965-1972 box, and the film (starring ex-Manfred Mann singer Paul Jones, with a scene of Arthur Brown performing “Nightmare” at a party), came out on DVD.

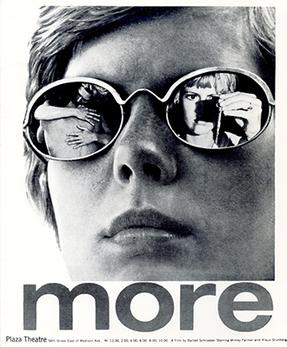

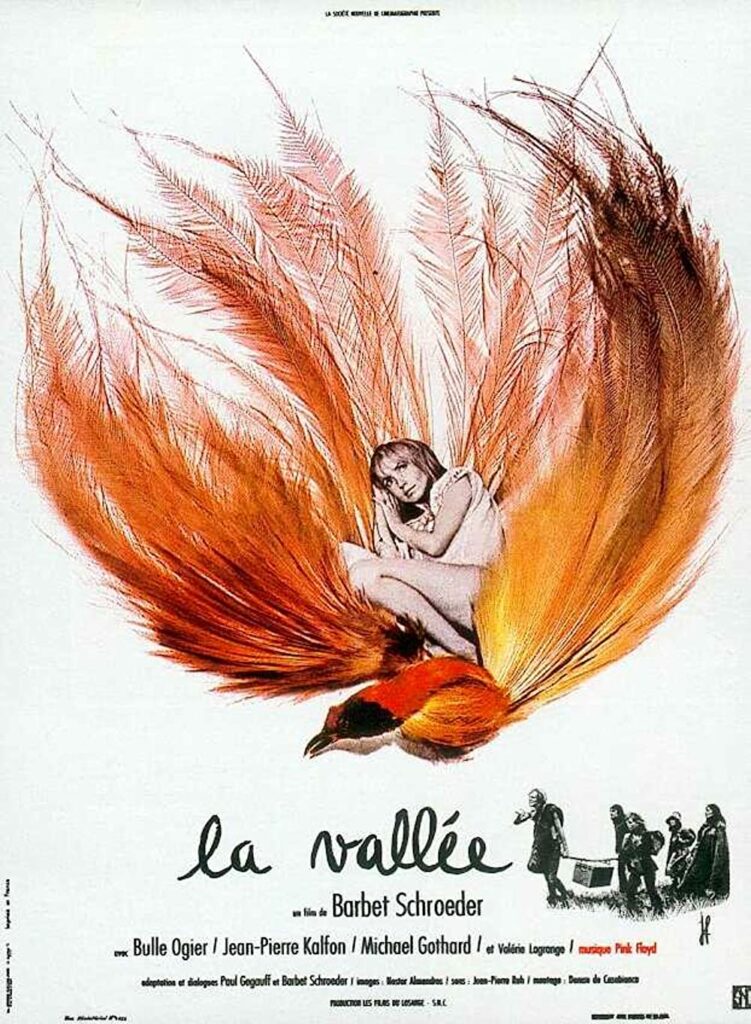

More famously, and in some ways infamously, Pink Floyd soundtracked Barbet Schroeder’s movies More and Obscured By Clouds (aka La Vallée), which generated full-length Pink Floyd LPs in 1969 and 1972 respectively. It’s likely lots more people have heard the soundtrack LPs than seen the films, though both movies are on Early Years 1965-1972, and weren’t too hard to find on video before that. The music doesn’t comprise huge parts of those films, in which Pink Floyd don’t actually appear. But it’s used pretty effectively, if rather sparsely and subtly, and considerably less in Obscured By Clouds than in More.

I’d seen both More and La Vallée quite a few years ago, and watching them again recently confirmed my memory that they’re pretty lousy — as films, not the soundtracks. And not in a laughably bad B-movie or lower-grade movie way — in a boring way. More’s young junkie protagonists are pretty unlikable characters, and the German student lead is actually kind of loathsome in his chauvinistic selfish hedonism. The opening credits, over which Pink Floyd’s “More” theme song plays, is by far the best sequence, as Floyd’s music and the impressive cinematography are the focus. La Vallée’s French hippies in search of paradise in Papua New Guinea aren’t much less offputting than More‘s characters, and the last half hour or so in particular is turgid.

The films are unworthy of both Pink Floyd and cinematographer Nestor Almendros, who’d get much wider attention for his work on Kramer Vs. Kramer, Sophie’s Choice, and François Truffaut’s The Last Metro, among other far more famous movies. Here’s one blooper that’s escaped most viewers’ notice: in More’s opening credits, David Gilmour’s last name is misspelled as “Gilmore.” Or maybe they wanted the “mour” spelled the same way as the movie’s title?

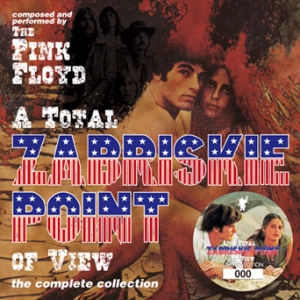

Some Pink Floyd music is also heard in Michaelangelo Antonioni’s 1970 film Zabriskie Point. Antonioni was an important filmmaker, and his movies Blow-Up (1967, with the Yardbirds playing one club scene with both Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page in the lineup) and The Passenger (1975, starring Jack Nicholson) in particular are excellent. Which makes it all the more baffling that Zabriskie Point, filmed in English in Southern California, is so terrible. Part of this can be blamed on his decision to cast two amateurs rather than professional actors as the leads, but it goes beyond that. The story’s slim and uninteresting, the other acting is wooden, and much of the movie, like the Schroeder films, is just boring. And the lead guy’s decision to paint his stolen plane with silly psychedelic graphics and return it to the airport he took it from—where he gets shot by law enforcement officials—is daft even in the context of daft hippie-era movies.

Like a good number of flops by noted artists, Zabriskie Point has its revisionist champions. Only a month or so before this post, The New Yorker gave it a brief near-rave review in advance of a revival screening, hailing it as “a daring and flamboyant blend of fiction and documentary…By way of wide-screen images filled with the giddy illusions and gaudy forms of American advertising, architecture, and technology, [Antonioni] realizes his freest, wildest aesthetic adventure.” As with Bob Dylan’s Self Portrait, to name one of many examples I can cite, a revisionist rave doesn’t change my original opinion.

Pink Floyd’s contributions are fairly good, though, including their atypically good-time folk-country-rocker “Crumbling Land”; the ominous “Heart Beat, Pig Meat,” which plays over the opening credits (and, like the opening credit/theme sequence of More, has music that’s far more interesting than the onscreen action); and “Careful With That Axe, Eugene” (here titled “Come in Number 51, Your Time Is Up”), which plays as a house is seen exploding in the desert in slow motion from several angles.

As many Floyd fans know, and some general rock fans know, the original intention was for Pink Floyd to do the entire Zabriskie Point soundtrack. They didn’t have such a great time collaborating with Antonioni, however, and ultimately the soundtrack just used these three songs, augmented by some cuts by other acts, including the Rolling Stones, the Grateful Dead, the Youngbloods, and John Fahey. Four unreleased Pink Floyd tracks from the sessions came out on an expanded two-CD version of the soundtrack, and lots more unreleased Floyd material intended for consideration for the soundtrack has circulated on bootleg.

Notable pieces that didn’t make the film include one that formed the melodic backbone of Dark Side of the Moon’s “Us and Them.” Another, likely intended for the surreal scene of couples making love in the desert, features the Floyd making snickering, sardonic jokes about devising a sort of sex soundtrack, including some blatant profanity that would have ensured it wouldn’t have been used, at least in a full unedited version.

Pink Floyd were considered for a soundtrack for a movie that would have been on the level of their musical contributions, Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. But Kubrick and the band didn’t agree on conditions for the music’s use. Nick Mason told a reader in Uncut in 2018 that it was “probably because he wouldn’t let us do anything for 2001…We’d have loved to have got involved with 2001–we thought it was exactly the sort of thing we should be doing the soundtrack for.” But 2001 was in production about three years before A Clockwork Orange, and Pink Floyd were far less famous then, so it seems unlikely Kubrick would have considered them for the earlier movie. In any case, 2001 or A Clockwork Orange both fared fine artistically without Pink Floyd music, though it’s interesting to speculate how 2001 might have been with Pink Floyd’s contributions.

In a way Pink Floyd, or certainly at least Roger Waters, got to soundtrack the film they wanted with The Wall, which in its way was as weirdly flawed and often hard to watch as More, La Vallée, and Zabriskie Point. After all that activity, the San Francisco short and the surreal The Committee—which isn’t great, but is certainly easier on the eye than the Schroeder/Antonioni efforts—might have been the best uses of Pink Floyd’s music in the movies. This doesn’t count Live at Pompeii, the early-‘70s concert documentary that, despite its own flaws, ably captures full live performances of early Pink Floyd standards.

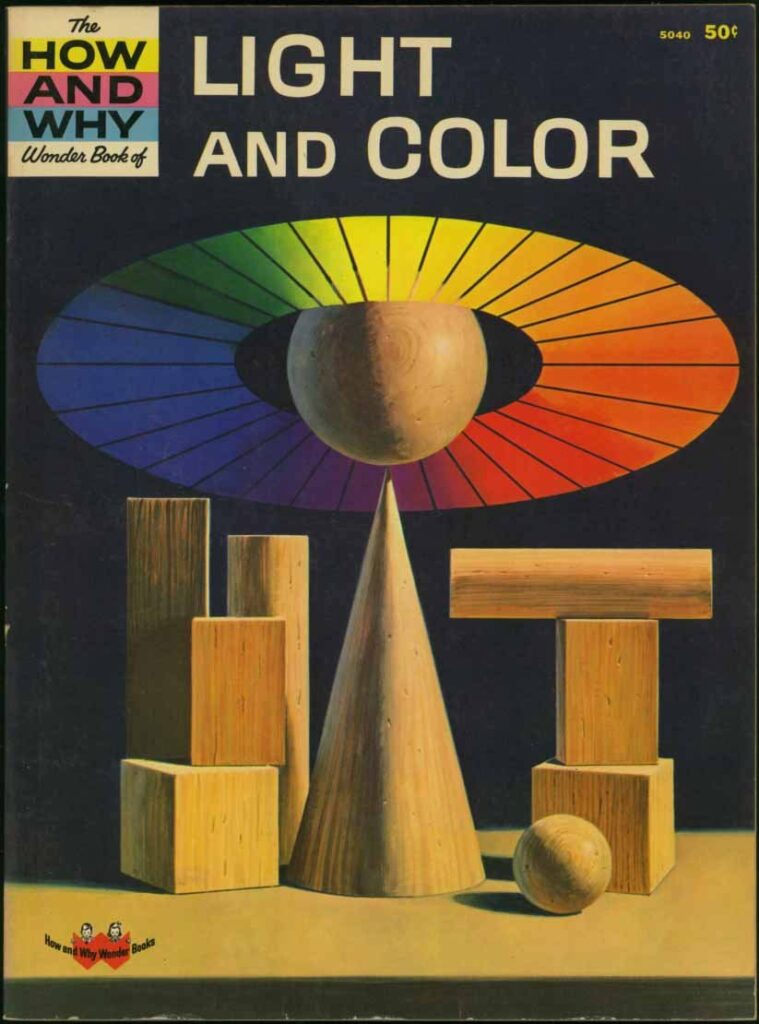

5. The Dark Side of the Moon cover origins. The Dark Side of the Moon has one of the most famous covers in history. But part of its inspiration came from an unlikely mundane source. Look at the cover of the 1963 book The How and Why Wonder Book of Light and Color:

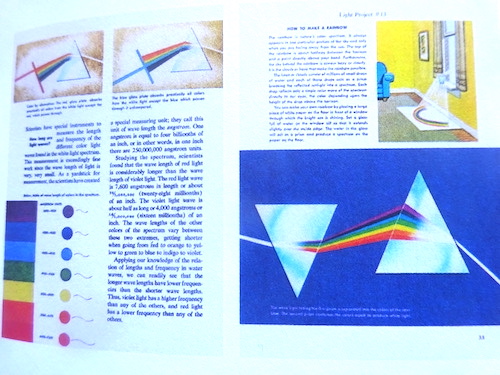

And, more notably, the graphics from a couple pages inside:

This reminds me of countless kid/young adult science books from the mid-twentieth century, and some Highlights-like magazines for kids that explained the world with colorful elementary graphics. This isn’t a hidden secret fanatical researchers discovered many years later for taking designers Storm Thorgerson and Aubrey Powell to task. Powell acknowledges these sources in his recent book Through the Prism: Untold Rock Stories from the Hipgnosis Archive.

I didn’t realize how many books center on the work of Hipgnosis, who designed most of Pink Floyd’s covers, and many others, some of them quite famous. There are at least half a dozen. Alas, there’s a lot of repetition between them. Through the Prism is about the best for historical text, along with perhaps Vinyl, Album, Cover, Art: The Complete Hipgnosis Catalogue. That includes some obscurities along with the famous sleeves, including some that aren’t nearly as impressive as the ones they did for Pink Floyd. Like this one from the early ‘70s for the obscure British group Toe Fat, which Powell acknowledges in The Complete Hipgnosis Catalogue was not one of their finer moments:

Urban legend has it that Toe Fat broke up, in part, because Hipgnosis wanted them to call their next album Toe Fu, and have a picture of a huge cube of tofu on the cover. To which Toe Fat retorted, “We’re not a bleedin’ health food store!” Well, it makes for a story, anyway, even if it’s not true.

Here are some more incidental side notes when you dig deep into the Pink Floyd saga:

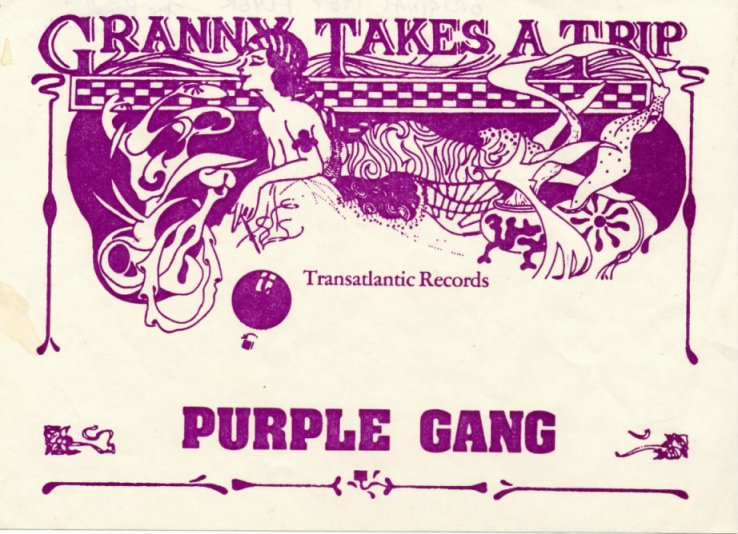

1. The Purple Gang demos. By the 2020s, most bodies of intriguing unreleased work by top classic rock acts known to exist have been issued or are at least in unofficial circulation, whether the Beach Boys’ Smile or the Beatles’ Get Back sessions. One of the few such items that no one’s ever heard, outside of the creator and at least one record producer, is a tape of Syd Barrett demos from around early 1967. Here’s what Joe Boyd told me in a 1996 interview (I don’t have an exclusive, he’s told plenty of others too):

“One of the great sorrows in my collection is that I don’t have the demo tape that Syd gave me of six or eight songs that he hadn’t recorded. I was recording a band called the Purple Gang and we were looking for material, and Syd gave us this tape. There were some terrific songs, very different from [what he ended up putting on his solo albums]. Strong, melodic, good songs.”

The Purple Gang’s vaudevillian music was far from early Pink Floyd, or rock, and hasn’t dated well or gotten even a small cult following. It’s a little hard to see how Barrett’s songs, even if they might have been castoffs of sorts, could have fit into their repertoire, or their potential maximized by the Purple Gang. Still, if Boyd’s description has even some validity, they’d be fascinating to hear. And if they haven’t turned up yet 55 years later, it might be something of a miracle if they’re ever found, if they haven’t been destroyed, lost, or erased.

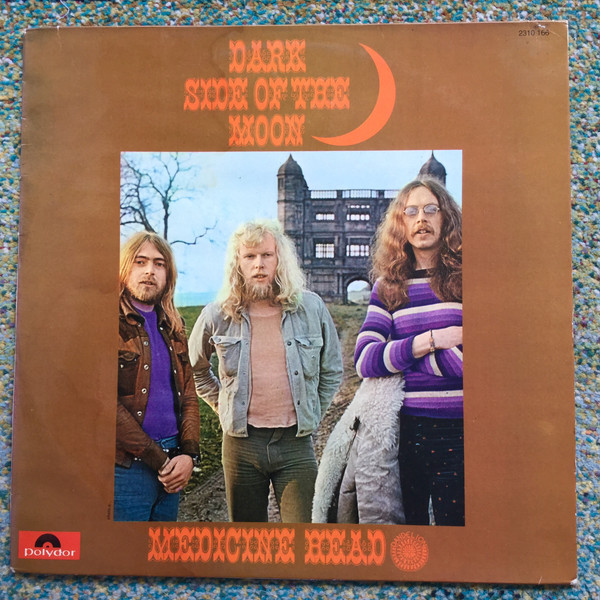

2. Medicine Head’s Dark Side of the Moon. It’s still not widely known—even by most of the tens of millions of fans who’ve bought The Dark Side of the Moon—that there was an LP with an almost identical title just a year earlier. And the artist wasn’t even that obscure, at least to UK audiences, though there are still barely any US listeners who’ve heard of them, let alone heard them. This is the British blues-folk-rock group Medicine Head, who actually achieved some significant commercial success in their homeland in the early 1970s.

Medicine Head had seven albums in the 1970s, and four British chart hit singles—“(And The) Pictures in the Sky” (1971, #22), “One and One Is One” (1973, #3), “Rising Sun” (1973, #11), and “Slip and Slide” (1974, #22). They had a connection to a much more famous group when ex-Yardbirds singer Keith Relf worked with them as a producer. Relf also joined the band on bass for a while, and is on their 1972 album Dark Side of the Moon. Not The Dark Side of the Moon—note the absence of the “The” at the beginning.

I’ve heard some though not all of Medicine Head’s records, and they’re not my thing at all. They have a rustic, at times almost skifflish sound, and not much in the way of memorable songs or to make them stand out much from many British blues or blues-influenced acts of the time. They don’t sound at all like Pink Floyd, even Pink Floyd at their bluesiest. But they did put out a record titled Dark Side of the Moon, and the year before Pink Floyd’s THE [capitals mine] Dark Side of the Moon.

I don’t know enough about the legal side of things to know if Medicine Head might have had grounds for taking legal action had Pink Floyd’s huge seller simply been titled Dark Side of the Moon. It did make it easier on Pink Floyd, however, that Medicine Head’s The Dark of the Moon didn’t sell well, clearing the path from much if any confusion with Pink Floyd’s 1973 album. Had Pink Floyd decided not to use that title for fear of overlap with Medicine Head’s record, it might have been called Eclipse, the title of the concluding track—not a bad title, but one that probably wouldn’t have served the group as well as The Dark Side of the Moon.

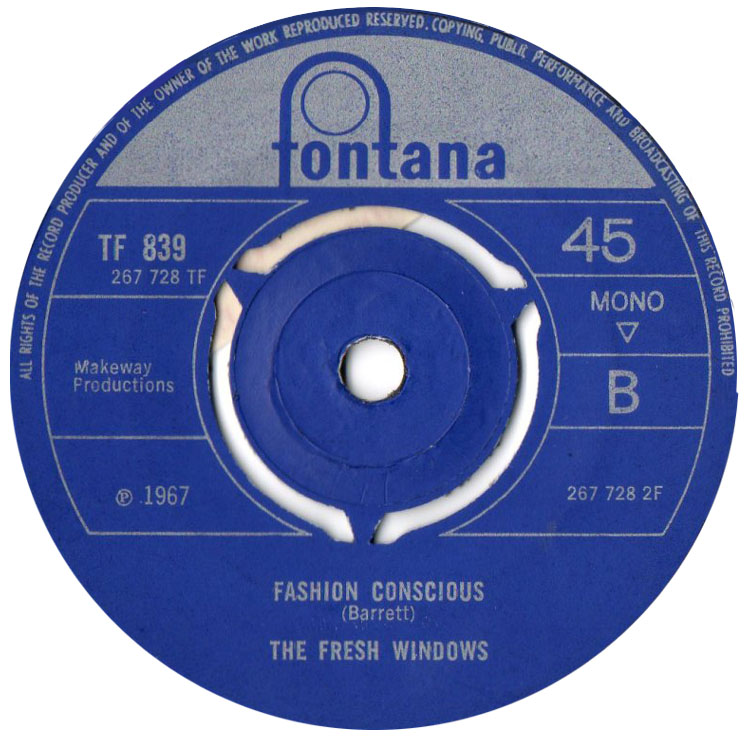

3. The Fresh Windows’ 1967 single “Fashion Conscious”—Syd Barrett under a pseudonym? Back in the very early days of compilations of obscure British psychedelic ‘60s flop nuggets—although it was already the early 1980s, well after the late ’60s—the key anthologies were the three-volume Chocolate Soup for Diabetics series. The first volume included a 1967 single by the Fresh Windows, “Fashion Conscious,” that was a quite good mod-psychedelic cut with biting humorous lyrics satirizing a trendy Carnaby Street-era girl. It’s not exactly like early Pink Floyd; it might be more like a slightly psychedelicized Kinks. But it has a playful yet seething vocal phrasing with some similarity to early Syd Barrett compositions, as well as a generally humorous yet penetrating aura that likewise can recall Barrett-era Floyd, if more slightly.

What really fueled speculation that the song might at least have been written by Barrett was the songwriting credit, “S. Barrett.” Could this have been a song Syd donated to another act, and could be maybe even have played or sung on the track?

There’s still not much known about the Fresh Windows, but it’s now known the answer is definitely “no.” The writer, singer, and lead guitarist was actually Brian Barrett, no relation to Syd. Some online posts speculate that the guy who put the unauthorized Chocolate Soup for Diabetics comp together deliberately and mischievously miscredited the composition to “S. Barrett” to generate such rumors.

Is there anything else by the Fresh Windows, considering the quality of “Fashion Conscious”? Just the other side of the single, “Summer Sun Shines.” And it’s not nearly as good.