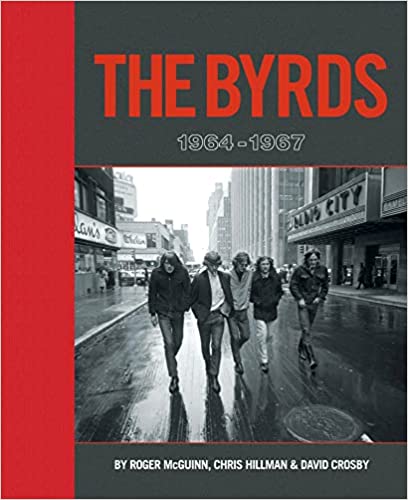

The new BMG book The Byrds: 1964-1967 presents 400 pages of photos from their prime period, with commentary by all three surviving original Byrds—Roger McGuinn, Chris Hillman, and David Crosby. Even by the standards of coffee table books, this is a literally heavy tome, weighing almost nine pounds. At about $150, it’s also pretty expensive. And it’s a photo book, not a standard narrative one. For a Byrds history, Johnny Rogan’s huge two-volume Byrds: Requiem for the Timeless remains the most thorough account, and indeed one of the most thorough accounts of any rock group.

Still, The Byrds: 1964-1967 is worthwhile if you’re a big Byrds fan, as I am. The photos are really good, and I haven’t seen many of them (some of them outtakes from sessions that generated familiar images, including record covers) before, although I’ve seen many Byrds photos. And the three surviving original Byrds’ quotes were done specifically for this book, not taken from archive sources.

This post is not a review of the book; there will be a several-paragraph one on my year-end best-of list. It won’t be a clarification of what’s wrong, either, as the volume’s refreshingly free of significant inaccuracies. In any case, those are made easier to avoid as the quotes emphasize perspectives and details of specific photos, not exactly what happened when. And the three admit when they don’t remember something.

But even having read so much about the Byrds (and interviewed McGuinn and Hillman), there were still some interesting things here and there I don’t remember reading about much or at all elsewhere. This post won’t try to cite all of them, but muse upon some aspects of their mid-‘60s career that some of the material brought to mind.

Jim Dickson: As the group’s original co-manager, and producer of their very good early demos circa late 1964-early 1965 (long officially available under variations of the Preflyte title), Dickson was enormously important to getting the Byrds off the ground. Crosby is quite negative about him in the book, however, calling him an “asshole” and “an absolute shit” within a few pages of each other. Maybe that’s something you’d expect from a character like Crosby, whose quotes generally have the bluntest and most caustic tone.

But Chris Hillman, who generally doesn’t have many bad words for anyone, says Dickson “had some good moments, but he would always revert to playing us off one another…he’d always find a way to go after one of us and pit us against everyone else.” Amplifies Crosby, “Dickson was violent, and not a good guy. He beat the crap out of Hillman very early on…Dickson was just not a good man.”

Yet Crosby also notes how important Dickson was to refining the sound of the early Byrds by giving them free access to World Pacific Studios, where they made rehearsal tapes that immensely accelerated their development. “Bands go through a period where they’re garage bands and they’re learning how to play and it takes them a long fuckin’ time,” he observes. “If you have to listen to a tape afterwards, it takes a lot less time. So that was something that Dickson did that was absolutely correct. Hearing ourselves shortened that garage band period to a tenth of what it normally would have been. We went really fast.”

I can’t think of another instance from this era where a band used this process to such great advantage. Of course studio time was (and is) expensive, and the Byrds had the great advantage of doing it for free after hours. But wouldn’t it have made sense for more groups to do something like this, if possible? And these days, when home studios are so much more common and relatively affordable, are there notable acts that go through this—not just rehearsing and recording, but intently listening and then going back to improve what they can do better—with as much intensity shortly after formation? Not so many that you hear about, anyway.

For what it’s worth, McGuinn also remembers how Dickson literally fed the Byrds before they made records, keeping them alive long enough to hit with “Mr. Tambourine Man.”

Michael Clarke’s drumming: Clarke’s drumming is sometimes not held in very high regard by critics. Or, at the least, some feel that his skills were limited, if sufficient for the Byrds’ purposes. It’s true that Clarke’s experience was very limited (apparently to informally playing some congas) before he joined, and that he was recruited primarily for his Brian Jones-like looks. This rather haphazard process of selection wasn’t so uncommon in 1960s folk-rock groups, where the ex-folkies who formed their cores knew how to sing and play guitars, but hardly knew any drummers, let alone had worked with any.

As Chris Darrow of another Southern Californian 1960s folk-rock group, Kaleidoscope, said when I interviewed him for my two-volume set of books on 1960s folk-rock (now available as the Jingle Jangle Morning ebook), Kaleidoscope’s John Vidican “was an 18-year-old hippie who looked pretty good, kind of the high school marching band drummer. He was the only one that had any kind of pop charisma in our band. These folk music guys, they’d never worked with drummers, so they just figured all drummers were the same. And if you could find one that looked cool, that’s pretty much what we all wanted. A lot of these guys, I think, did get picked on kind of how handsome they were, whether or not they could play the drums.”

So it’s cool to read the other Byrds actually complimenting Clarke’s musical abilities here. Crosby: “Michael turned out to be really good. He had a good sense of time, he looked absolutely great, and he was a sweet guy.” But Hillman’s praise comes with some reservations: “He could be lazy as all get out, but when he was on, he was good.” Chris, however, does feel Clarke could have been better: “Mike was a natural drummer, but could have benefited from some direction. Do you know how many drummers offered to take Mike under their wing? Hal Blaine and different studio musicians were ready to help Mike any way they could. I said, ‘Do it, Michael.’ He didn’t want to do it. He had the talent, but not always the drive.”

It’s unfortunate, of course, that the late Clarke didn’t have the opportunity to contribute to the book, which unfortunately doesn’t go into details about why he left the Byrds near the end of 1967. Although it’s beyond the scope of this volume, Michael couldn’t have been that lacking as a drummer, since soon enough he was drumming behind Hillman in the Flying Burrito Brothers, and afterward was drummer in the musically unremarkable but sometimes commercially successful Firefall.

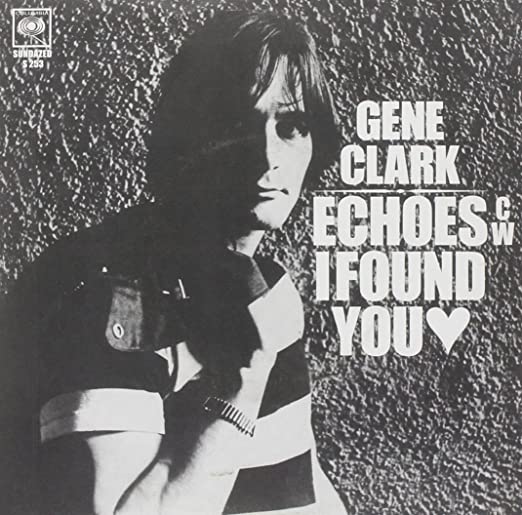

Gene Clark: While acknowledging Clark’s fine songwriting, Crosby also admits, as has long been reported, that he pushed Gene somewhat to the background. “He couldn’t play guitar that well and I could, so I kind of nosed him out of the second guitar part.” Along a less traveled path, he adds, “He wanted to be the lead singer, and it was obviously Roger. Roger was five times as good at it.”

While the early Byrds are often hailed for their multi-part harmonies (Hillman not yet singing ,as he would starting in 1966 after Clark’s departure), Crosby also offers, “Almost nothing was three-part harmony. Gene and Roger would sing in unison on the melody, and I’d sing harmony. The structure of Gene’s songs lent themselves to me being able to do a non-parallel harmony, which I really liked to do.”

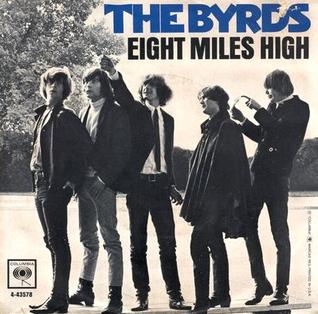

Crosby on McGuinn: Crosby has often had less than flattering things to say about his bandmates, in the Byrds and other outfits. But he’s extremely complimentary in his remarks about Roger in this book, on several occasions. After praising Clark’s early compositions, David elaborates, “Roger was playing better than anybody else, so he made Gene’s songs sound really great…Roger upgraded them. The minute Roger played them, they were better songs. And then I put harmony on them and that was it.” On their Dylan covers: “Roger was the best translator of Bob’s stuff. Nobody ever made records out of Bob’s music better than what Roger did. And I helped too.” On McGuinn’s solo on “Eight Miles High”: “That’s Roger listening to Coltrane and taking it in. He’s a genius at it. Absolutely better than anybody at that kind of adaptation.”

Terry Melcher: Crosby has some very ungracious things to say about the producer of the first two Byrds albums, Terry Melcher. According to David, “Melcher couldn’t produce a Kleenex box. He knew nothing about audio, nothing about recording, nothing about songs, nothing about our band. Knew nothing about anything. The people who ran the record company were failed shoe salesmen. They knew nothing about music, but he was the son of a movie star [Doris Day], so there you go.”

McGuinn, always more diplomatic, is quite complimentary about Melcher, whom he “thought was a good producer for that AM mono single kind of record, and I believe he was a big part of the Byrds’ success.” As for the possible real reason for Crosby’s grousing, he points out that “Terry didn’t like David’s songs, so he wasn’t putting them on the album. That was the key point that they disagreed on…We left the song selection up to the producers for the most part. We would kind of lobby them and say, ‘You know, here’s a song…check this out.’ But the producer would pick the songs, which is what got David angry with Terry Melcher.”

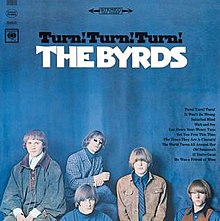

Maybe Crosby was particularly unhappy the Byrds didn’t release his composition “Stranger in a Strange Land,” which got as far as an instrumental backing track, now available as a bonus cut on the expanded CD edition of Turn! Turn! Turn! San Francisco early folk-rock duo Blackburn and Snow did an excellent version on a single, but the Byrds never put out a finished vocal arrangement.

Here’s another way Melcher upset Crosby, this from Johnny Rogan’s Byrds: Requiem for the Timeless: Vol. 1, and not related to one of David’s compositions. For their version of “He Was a Friend of Mine” on their second album, he complained, “Remember that organ note that goes all the way through it that seems very out of place? Terry put it on after we finished the song without even asking us, and mixed it that way. And the tambourine…I could have popped him in the lip for that.”

Hillman comes down on Melcher’s side, if sides have to be chosen. “He was encouraging to me because he knew I was just learning the bass in some ways,” he remembers. “He was very helpful, and I liked him. I never had a problem with Terry ever. But David locked horns with him all the time.”

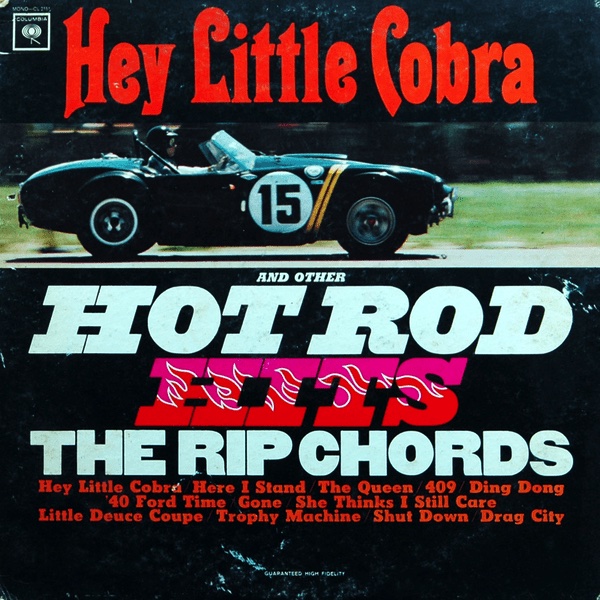

However much nepotism might have helped Melcher get his position at Columbia Records, it seems unfair to dismiss him as knowing “nothing about audio, nothing about recording, nothing about songs.” With future Beach Boy Bruce Johnston, he’d co-produced the Rip Chords’ early 1964 Beach Boys-lite hit “Hey Little Cobra,” as well as often producing and writing with Johnston on other records. On an unreleased tape of the Byrds working on the Gene Clark song “She Has a Way,” you can hear him making specific constructive and tactful suggestions, even competently singing part of the tune to illustrate points.

Billy James, manager of information services for Columbia’s Los Angeles office at the time (and author of the liner notes for the Byrds’ first album), characterized Melcher as a hip rocker, and far from a failed shoe salesman. “Bruce Johnston and Terry Melcher were the first pals I had in my life who loved rock ‘n’ roll, who were in rock ‘n’ roll,” he told me. “Through my friendship with them and my respect for them, I began to develop an appreciation for rock ’n’ roll.” Although the appreciation was not always reciprocated by less open-minded Columbia personnel than James, who elaborated: “The West Coast A&R department was something of a thorn in the side of the home office in New York. Terry and Bruce were not typical corporate record company producers. There was a lack of comprehension and appreciation for the changes that were going on in popular music in general, and for what Bruce and Terry were doing in particular, at Columbia.”

As a final note about Melcher, a 1965 photo in the book raises some curious questions. It’s been documented that McGuinn was the only Byrd to play (and McGuinn, Clark, and Crosby the only Byrds to sing) on “Mr. Tambourine Man” and its B-side, “I Knew I’d Want You.” It’s also been documented that the full Byrds then played on everything from then onward (though Jim Gordon took the place of Clarke for some of The Notorious Byrd Brothers sessions). “We were playing well, but it’s not the smooth ‘session player sound,’” says Hillman in the book. “It’s a far more interesting and real sound that only the original Byrds could have produced.”

But the photo in question shows McGuinn, Clark, Crosby, and Melcher in the studio with three session musicians. One of them is definitely Bruce Johnston. I’m not sure about the other two guys, though at a guess they could be Billy Strange and Larry Knechtel. Hillman and McGuinn are mystified as to what’s happening in the picture, Roger admitting, “I don’t know what’s going on.” Crosby and McGuinn are playing guitars as an instrument-less Clark looks on; Johnston’s at a keyboard; the other two guys are holding guitars.

Could the session guys just be hanging out and giving them pointers, maybe between doing non-Byrds sessions with Melcher? Or could session musicians actually have played on Byrds records besides their first single? The photo probably wasn’t taken when “Mr. Tambourine Man” was recorded, McGuinn noting that “David is there, and he didn’t play on the ‘Tambourine Man’ session.”

The “Eight Miles High” single picture sleeve session: Some Barry Feinstein photos make it clear that the great picture sleeve for the “Eight Miles High” single, where Michael Clarke is about to flick a spoon at an oblivious David Crosby’s head, was taken in mid-1965 in Chicago. The book, however, doesn’t include the actual photo from the picture sleeve. Which I would have liked, in part because that might have given McGuinn, Hillman, and Crosby a chance to explain what was happening in that wonderfully goofy photo. It’s a minor missed opportunity, and I wonder if the three recognized the picture as coming from the session that generated the “Eight Miles High” sleeve.

The weird Hullabaloo clip: When the Byrds sang “The Times They Are A-Changin’” on Hullabaloo in late 1965, it was on a set that was bizarre even by the oft-absurd standards of the era. Playing amidst some fake foliage, the Byrds were surrounded by models in hunting outfits wielding shotguns, with some fake dogs. What was the possible rationale?

Crosby explains: “They said, ‘OK, the Byrds are coming to the program. What do we do for birds? OK, we’ll have people hunting them.’ That’s their idea of how to relate? Hunting dogs and girls with shotguns…We thought it was unbelievably hysterically stupid. You can tell from how thrilled we look.”

Unused Turn! Turn! Turn! liner notes: There’s not much memorabilia in the book, but an item of great interest reproduces the unused liner notes publicist Derek Taylor wrote for their second album, Turn! Turn! Turn! These refer, with extreme (by the standards of the day’s notes) candor, to a physical fight between Crosby and Clarke in the studio; to Crosby undermining Clark’s confidence as a guitarist; to McGuinn and Crosby maneuvering to let only three Clark songs on the album; and to Columbia manufacturing 200,000 unused sleeves for a “The Times They Are A-Changin’” single that didn’t come out. And this is from a publicist!

These kind of frank insights into a band’s conflicts were rare in any kind of press in the mid-1960s, and certainly unheard of in liner notes. But it’s definitely valuable as a historical document, even if no one should have been surprised that it wasn’t used on the LP’s back cover. Did Taylor submit these as a kind of dare or joke, knowing how unlikely they would be to get approval? And did the Byrds even see these notes at the time? (The survivors don’t comment on them in the book.)

Gene Clark Goes Solo: The Real Story? The usual explanation for Clark leaving the Byrds in early 1966 is that he wasn’t up to touring with the group and generally having trouble coping with the demands of stardom, and specifically that he didn’t want to fly. McGuinn says in the book, and has said in the past, that there might have been some other motivations at work. “Dickson and his business partner Eddie Tickner had been thinking about spinning him off as another Elvis,” Roger remembers. “I found that out years later from Dickson, when he was very sick. My wife and I went to visit him in the hospital, and I guess it was like a deathbed confession. But Jim didn’t die then, and he later denied he said it.”

Whatever Dickson and Tickner might have been thinking in 1966, it seems strange to envision Clark as another Elvis, or even as a significant solo star. He was more talented as a songwriter than a singer, and not wanting to fly—therefore limiting his touring possibilities—would have been a significant disadvantage. But while Clark’s sizable cult following might disagree, I don’t see how his songs could have been considered sure-fire commercial bets, though he did co-write (according to some accounts as the primary author) “Eight Miles High,” and wrote “You Showed Me,” demoed by the Byrds in the Preflyte days and a hit for the Turtles in 1969, with McGuinn.

It doesn’t often work for a former member of a popular group, and the group itself, to maintain successful separate careers after separating. Such was the case with Clark, whose debut solo album failed to make the Top 200, and who never did sell many records as a solo artist, as much as his cult reveres some of his work. In fact all four of the other original Byrds had greater post-Byrds commercial success than Clark did.

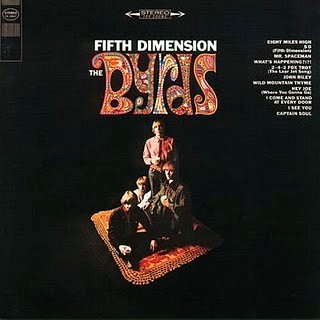

The Fifth Dimension Album Cover: I’ve always thought the cover of Fifth Dimension that shows them on a magic carpet of sorts is cool. It’s hipper than most 1966 rock albums, and there are some outtakes of photos from the session in the book. So it’s a little bit of a surprise to find the Byrds didn’t have much to do with the concept.

McGuinn: “I don’t know what the thinking was with the magic carpet for the Fifth Dimension album cover. We didn’t have much say in the Columbia art department’s ideas. They just came up with things, and we went along with them.”

Hillman: “I don’t know who came up with this magic carpet idea, but they brought in lunch for us, and we’re just there [in one of the book’s outtakes] eating lunch and drinking coffee.”

Crosby: “When you look at how people tried to envision some framework to put us in, visually, they did funny shit like that over and over. They tried to shoot us in ways that were somehow relevant, but it never really worked.”

Linda Eastman: There are a few pictures of the Byrds in New York in late 1966 taken by Linda Eastman, two years before she took up with Paul McCartney. Her abilities as a photographer have sometimes been chastised, but Crosby matter-of-factly counters this impression: “Linda was taking pretty good pictures of a whole lot of people then. She was one of the only photographers we liked. She was comfortable with musicians, but mainly we just liked her because she was a good photographer.”

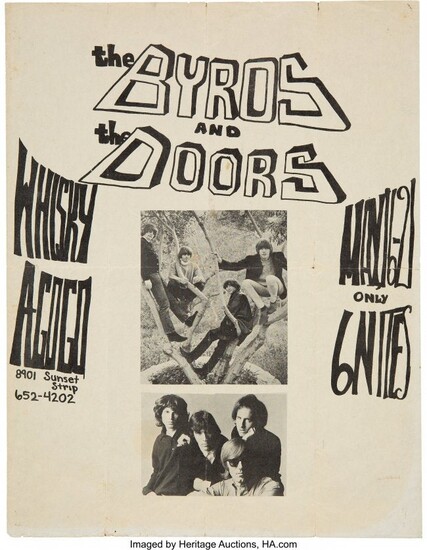

Crosby on the Doors: He didn’t like them, and more than fifty years after Jim Morrison’s death, he doesn’t mince words here: “I didn’t like the Doors. I was almost the only person who didn’t, but I just didn’t like them. They didn’t have a bass player and they didn’t swing. They were like a square wheel. If you listened to them play live, they just were never quite there. I also didn’t like Morrison as a singer. He was more of a poseur. He tried to be frightfully dramatic and mysterious, but he couldn’t really sing. I thought they were a crap band. And I said so, too, which earned me no end of enmity.”

His remark didn’t pass unnoticed by Doors drummer John Densmore. “Joe Hagan’s appreciation for David Crosby [‘Imperfect Harmony,’ Jan. 23] is imperfect, indeed,” read his letter in the Los Angeles Times on February 5, 2023. “I don’t agree with Hagan that ‘Crosby’s music backed up all his talk.’ In calling my band (The Doors) ‘crap,’ Crosby revealed that his singing and songwriting ability compared with Jim Morrison’s (who he regularly dissed), is clearly the lesser of the two.”

Larry Spector: Crosby didn’t like Jim Dickson, and he didn’t like the manager they took after cutting ties with Dickson and Tickner, Larry Spector. “I don’t think you really want me to tell you what I think of Larry Spector now,” he says. “He was a sneaky little guy, dishonest and bad.” Crosby has company on this count, Hillman adding, “He was absolutely horrible—dishonest and everything you could possibly imagine in a bad manager.”

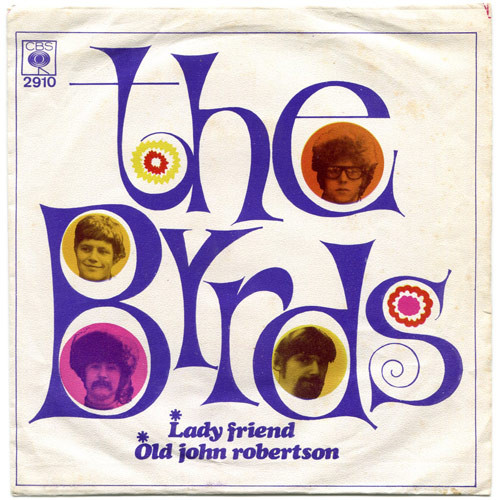

“Lady Friend”: This non-LP, non-hit single was written by Crosby, and according to Hillman, “we really had it sounding great. Then [David] sneaks back into the studio and changes the vocal parts and puts these horrible horn parts on it. Ruined it. It became full of unnecessary noise packed into these tracks. It was a great song, but then it wasn’t so great.”

Hillman has discussed Crosby changing the vocals before (in Byrds: Requiem for the Timeless), but here he remembers David also inserting horn parts. Yet there wouldn’t be much in the middle instrumental break without those horns, which Crosby described (also in Byrds: Requiem for the Timeless) as “an idea of mine that I wanted to try. I envisaged a little French horn fugue in the middle of it.” It makes one wonder what might have been in a previous arrangement. Chiming guitars, or something else? Alternate arrangements or takes like that haven’t circulated.

It’s also a little odd that I can’t find any credits for who played the horns on “Lady Friend.” The Byrds had effectively used brass before with trumpeter Hugh Masekela on “So You Want to Be a Rock’n’Roll Star,” and the book has a couple cool color shots of Masekela performing with the Byrds at the Magic Mountain Music Festival on Mount Tamalpais in Marin County in June 1967. Could Masekela have been playing on the “Lady Friend” single?

Gary Usher: He produced the Byrds’ 1967-1968 records, and McGuinn keeps up the diplomatic good vibes with some staunch praise. (There’s nothing in the book about Fifth Dimension producer Allen Stanton, who seemed more like a Columbia representative keeping general tabs on the sessions than an active creative ingredient.) “Gary Usher was great,” McGuinn enthuses. “It was around this time that the Beatles were doing sound effects, and Gary came up with a lot of ideas in that vein—like a door slamming, pounding on a piano, and backwards tape…Gary was one of the first guys to take two eight-track machines side-by-side and synchronize the tape to go out of one into another to get sixteen tracks out of it. It was pretty clever…He was a fun guy to work with. I really enjoyed him.”

The End of the Era: As I mentioned, there’s no explanation of how and why Clarke left, but there’s a hint in one of the captions of a photo from late 1967, after Crosby had been fired. Next to a photo of the trio playing at the Golden Bear in Huntington Beach, Hillman comments, “You don’t see many photos of us playing as a three-piece, but we hacked it out and we did it. It was a little hard. Mike was thinking, ‘I’m getting out of here.’”