Reissue trends of the last few years continued apace in 2022, at least for the kind of reissues I want to hear. Just a couple of items on this list are from artists with whom I was previously unfamiliar, or virtually unfamiliar. Most of them are expansions of material I already had, or focus on BBC/live/demos/outtakes that, even if very good, don’t measure up to the cream of the artist’s output. Some of them are very expensive and large box sets, whether anniversary editions or not.

Still, this list does have a mix of interesting reissues of artists ranging from very obscure to the most famous of all. The most famous of all gets the #1 position, as they probably will if their reissue program continues to generate superdeluxe editions of albums from their catalog.

1. The Beatles, Revolver super deluxe edition (Apple/Universal). Since 2017’s Sgt. Pepper super deluxe box, these multi-disc editions from the Beatles’ catalog have become an annual event, though they’re not proceeding in chronological order. In 2022, it was time for Revolver, and time for another vexing decision as to where to rank something like this. On its own, the original LP would of course automatically be at or near the top of a reissue list. While this isn’t merely a reissue of the original album (though that’s here), and has a couple discs of largely unreleased extras, the packaging is by no means the best value for money it could have been. And the extras aren’t as special as they are for other periods of the Beatles’ career, though they’re worthwhile and more interesting than I anticipated.

The basics are that if you get the five-CD version, as I did, one CD has the original mono master; another a new stereo mix overseen by Giles Martin; and another a mere EP’s worth of stereo and mono mixes of the “Paperback Writer”/“Rain” single, recorded during the Revolver sessions (but not released on the original LP). I’m not nearly as into discussing the merits of new mixes and/or mastering on previously available material as many critics are, not finding them as different from what I’ve previously heard as many do. My focus, as a listener and in this review, is on the rarities.

Revolver didn’t generate nearly as many interesting outtakes and alternates as some other Beatles albums, like The White Album, whose deluxe had many, and some (particularly the disc of demos) that were very good. There were no songs they worked on during the sessions that didn’t get on the LP or single. While all of those sixteen songs except “Good Day Sunshine” are represented by alternates or rehearsals, some of them aren’t much different from the official versions, or are backing tracks, fragmentary rehearsals, or variant mixes. A few were already issued a long time ago on Anthology 2, although here they last a little longer and have some more pre- and post-take chatter.

But there are some exceptions, and at least one genuine surprise. Take 1 of “Love You To” is unplugged, with some nice Paul McCartney harmonies that didn’t survive to the final arrangement. The base take of “Rain” is presented at its actual faster speed before it was slowed down for the single, and while that might sound like an academic difference, it’s almost rapid-fire compared to what we’re used to, particularly in Ringo Starr’s much-praised drumming. The earlier, more Byrds-like take 2 of “And Your Bird Can Sing” is finally heard without the giggles that distracted mightily from enjoying it on Anthology 2, and take 5 is, as detailed in Mark Lewisohn’s The Beatles Recording Sessions, notably heavier than the Revolver version. A basic acoustic solo Lennon demo of “She Said She Said” has different and cruder lyrics, though that’s long circulated on bootleg.

The big surprise is a “songwriting work tape”—a home demo, I’d guess—of John Lennon singing and playing a verse of “Yellow Submarine” on his own. It’s only about a minute, but has a key lyric difference, changing the words to “in the town where I was born, no one cared.” That’s a sentiment that fits Plastic Ono Band more than the #1 Ringo-sung hit single, and also evidence that Lennon’s role in writing the song was greater than most had realized, since it’s usually been assumed that McCartney wrote virtually all of it. A longer songwriter work tape has both John and Paul, singing two of the three verses that would end up on the studio version with only acoustic guitars and obvious camaraderie. That’s more evidence that they were closer collaborators in the song’s composition than the usual way it’s told.

The Revolver LP was only 35 minutes, and the mono master and stereo mix could have fit on one disc, presumably lowering the price. While the outtakes/alternates discs had just a little more material than could have fit on one CD, they’re only between 40 and 41 minutes each. It seems a few more tracks could have been added to each, even if they were more marginally different from the familiar versions than most of the cuts that were selected. As compensation, at least the package includes a 100-page hardback book with lots of inside info about the songs, recordings, and general history of the Beatles at the time of the sessions, as well as many photos and illustrations.

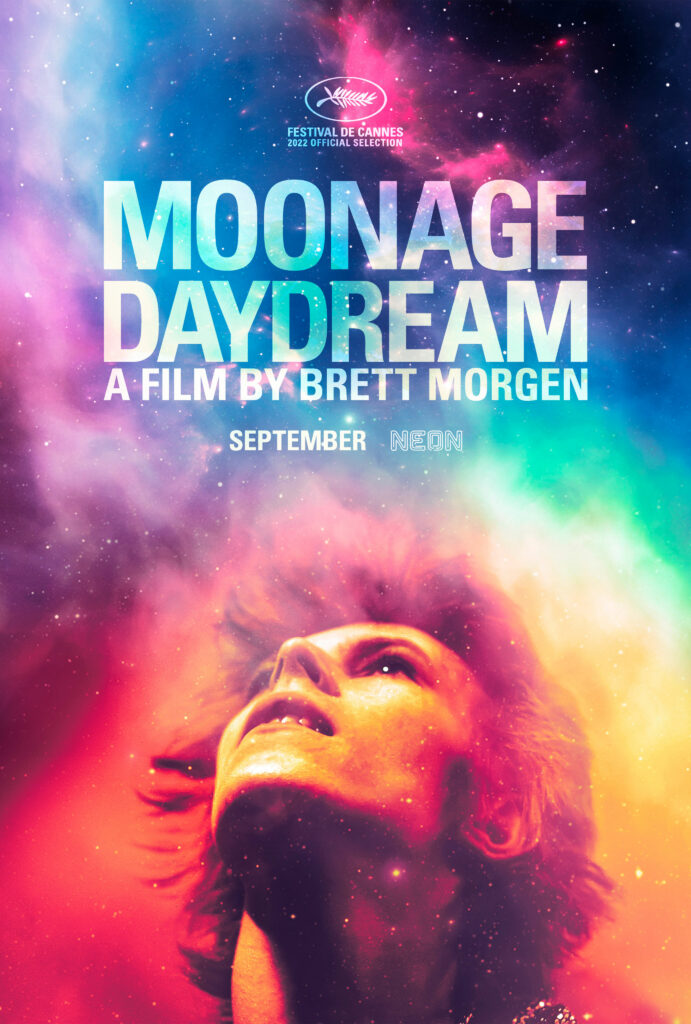

2. David Bowie, Divine Symmetry (Parlophone). Subtitled “The Journey to Hunky Dory,” this is more like a five-disc expanded box of his 1971 album Hunky Dory. The tracks from the original LP are here, if only on the Blu-ray audio disc (the other four discs are CDs), though just about anyone who buys this must already have the original Hunky Dory in some form. But most of this features material that wasn’t released at the time, and in fact most of this wasn’t previously issued anywhere. These include demos, 1971 BBC recordings, a live September 1971 show, and numerous rare/unreleased mixes. That makes this a better value for money than many an expanded reissue, like the Revolver box reviewed above.

Although some of the demos (all of which are featured on CD 1) are lo-fi, it’s the most valuable disc, as some of the songs are not available elsewhere in any form, and some of the familiar ones significantly different from the standard arrangements. While none of the half dozen songs that wouldn’t find official release are striking enough to cause wonder that they didn’t get on record at the time, they are decent and at times close in quality to his official early-‘70s output. That’s particularly true of “King of the City,” which has the yearning pensive quality, unexpected melodic shifts, and background harmonies found in much of his Hunky Dory-era songwriting. “How Lucky You Are,” one of the more developed extras, has the ominous piano-paced cabaret flavor of some of his less upbeat early-‘70s work. The demos of compositions that would be on Hunky Dory often offer a nice contrast, as so many decent demos by major artists do, for much more basic arrangements with an intimate quality. Even the lowest-fi tracks have appeal for their solo almost folky performances, like a version of “Quicksand” recorded in a San Francisco hotel, and a haunting “Amsterdam” where he sings in a lower register for the second and third verses.

The BBC material comes from programs in June 1971 and September 1971, and about half of it hasn’t previously been officially issued. Bowie’s underachieving a bit on the June program, in part because he altruistically let friends—George Underwood, Geoff MacCormack, and Dana Gillespie—take lead vocals on some of his compositions. The version of “The Supermen” is a standout, but the cuts sung by others prove he was the better singer, sometimes by far, of that material. Things are more serious on the September session, his vocals, 12-string guitar, and piano accompanied only by Mick Ronson on guitar, bass, and backup vocals. With five songs from Hunky Dory, another good version of “The Supermen,” and “Amsterdam,” these again are worthwhile less slickly arranged counterparts to the fully produced ones on the LP.

The live show from Aylesbury, England on September 25, 1971 has long been bootlegged (though it went through some sonic cleanup here), and has sound quality that varies from good to slightly subpar. Some of the songs feature just Bowie and Ronson, but others the full Spiders from Mars, with Tom Parker on piano. These aren’t the best versions you’ll hear, and Bowie seems uncharacteristically nervous at times. But it’s still good and interesting to hear him at the relatively formative stage of the Ziggy phase, and some of the numbers are uncommon, like “Buzz the Fuzz,” Chuck Berry’s “Round and Round,” and “Waiting for the Man” (also heard as a San Francisco hotel performance on the demos CD). It’s unfortunate this doesn’t include “Queen Bitch” for technical reasons, as on the bootleg you can hear him introduce it as a song by the Velvet Underground “who aren’t that well known.” A few lusty cheers confirm there are at least a few people who’ve heard of them, prompting Bowie to retrace: “Sorry, a very well known band over here called the Velvet Underground. They don’t know about them in Beckenham [the South London suburb where Bowie lived in the early ‘70s], I’ll tell you!”

Disc four fills out the set with numerous alternative/rare mixes/versions, including a few fair outtakes from around the time of Hunky Dory: “Bombers,” “Lightening Frightening,” and “Amsterdam” (the last of which showed up on a B-side). Unlike many such mixes (often recently created) that puff up the list price of many archival boxes, these do sometimes have noticeable differences, though many will need to follow along with original Hunky Dory co-producer Ken Scott’s detailed notes in the accompanying book to catch all of them. These include a different saxophone solo at the end of “Changes,” an earlier take of “Quicksand,” and some very faint chatter at the end of “Life on Mars” where you can hear Ronson cursing.

Unlike the majority of listeners who follow Bowie’s work from this period, I prefer the harder and edgier sound of his previous album, 1970’s The Man Who Sold the World, to the lighter and somewhat poppier Hunky Dory. But this is a good expansion of his work from this creative era, and while dedicated fans might wonder about the absence of versions of “Moonage Daydream” and “Hang Onto Yourself” on singles credited to Arnold Corns (which were Bowie tracks in all but name), maybe those will appear on an upcoming Ziggy Stardust box. Some, such as myself, will find the Blu-ray disc an unnecessary addition that jacks up the list price, considering most of it has material found elsewhere, whether the original Hunky Dory LP or tracks found on CD elsewhere on this box.

To ease the pain of the high list price, the packaging is superb, with a 100-page hardback book of detailed liner notes, reprints of vintage press releases and articles, memories of the live Aylesbury show, and numerous photos and illustrations. There’s also a facsimile reprint of a “Hunky-Dorey” (sic) student notebook with drawings, handwritten lyrics, what look like set lists, and other miscellaneous notes, though it’s not explained what these referred to—perhaps that information’s not available. To get the David Bowie/Hunky Dory tote bag and poster given away at least one major independent record store, you had to buy this very quickly after its release, as I was able to do to receive those unexpected bonuses.

3. Duffy Power, Innovations (Repertoire). In another of the “this would have ranked higher if” qualifications that dot my lists, this would have had a higher ranking if all the material hadn’t been previously reissued on various compilations. Fourteen of the tracks, in fact, came out back in 1971 on the LP Innovations, itself reissued in 1986 under a different title, Mary Open the Door. Confusing the situation more, everything on Innovations was recorded in 1965-67. Keeping his discography straight isn’t the main reason to listen to this or Power, however. It’s vital because it’s excellent and largely overlooked British blues-rock, with more of a folk-blues-jazz flavor than most of the genre. And this reissue of Innovations is bolstered by eleven other 1965-67 tracks that have appeared on other compilations. This 25-track CD is the first one to assemble everything from Power’s most productive period onto one place, and it hasn’t previously been easy to find all the bonus cuts in particular as they’ve been spread out on various Power anthologies. Even if you’ve already managed to get everything (I have, I confess), it could be worthwhile for that reason.

This material’s notable for the stellar, nay legendary, backup musicians alone, including at various times Jack Bruce, John McLaughlin, and Pentangle’s rhythm section, Danny Thompson and Terry Cox. While Power might not have the lowercase power of some of the top British blues-rock belters, he has an ingratiatingly versatile, likable blues-folk-rock-jazz delivery, and wrote (sometimes with McLaughlin) good material in that vein, most of these songs being originals, with some occasional covers. The acoustic bass heard on much of this gives it a different vibe than the more typical heavier British folk-rock approach, and some jazzmen on drums (Phil Seamen and Red Reece) lend a jazzier tone too. Almost all of the tracks are solid, and some great, like “Rosie,” the soul-influenced “Mary Open the Door,” the propulsive “Little Boy Blue,” and “Louisiana Blues,” a solo performance which has some amazing creepy slide blues guitar from Duffy himself.

While the tracks that didn’t appear on Innovations as a whole aren’t as consistent as the original LP, they’re decent and occasionally up to Innovations’ standards, especially the ominous “I’m So Glad You’re Mine,” a cover of Oscar Brown Jr.’s “Rags and Old Iron,” and “I Want You to Love Me,” which has more of his spooky acoustic blues guitar playing. Note that while the bonus tracks include two songs also found on Innovations, these aren’t mere alternates, but substantially different versions that appeared on a 1966-67 French EPs, though they’re a little more polished and not as good. There are two versions of “Hound Dog,” and completists note that the one that finishes this collection, from a 1966 French EP, was only reissued once, and then way back in the late 1980s on the various artists compilation-reissue The British R&B Explosion Vol. ’62-’68. With good liner notes and a few booklet illustrations, this is the definitive anthology of Power’s mid-‘60s work, and recommended to any fan of early British blues-rock.

4. Neil Young, Harvest 50th Anniversary Edition (Neil Young Archives). Kind of like the Beach Boys and Jimi Hendrix, Young’s catalog releases have become so frequent and expansive that more vintage material often appears on an annual basis than fresh material often did doing their primes. And as with the Beach Boys, Hendrix, and some others, a fervent fan base does not welcome even mild criticism of some of these projects, even though much of it is marginalia compared to their core discography. This five-disc Harvest box is more than marginalia, however, even if there’s not much hardcore collectors don’t already have. The big prize is the previously unreleased two-hour documentary DVD Harvest Time, based around footage taken (often in the studio, sometimes elsewhere) of Young and associates during the making of Harvest. It’s also been screened as a stand-alone film, and so is reviewed in much more depth in my best-of list for 2022 music documentaries. My basic summary is that it’s worthwhile for the studio performances in various locations (some with the London Symphony Orchestra), some casual performances outside the studio, and some interview footage, although some of the content’s superfluous or drags, especially on the occasional instrumental studio jams.

Otherwise, the box does include the original album, something virtually anyone who buys this already has in some form. There are decent outtakes, but a mere three (“Bad Fog of Loneliness,” “Journey Through the Past,” and “Dance Dance Dance”) on a CD EP of sorts. Another very good, if a bit brief (32-minute), DVD has the fine solo acoustic concert broadcast on BBC TV on February 23, 1971, though that’s circulated among collectors for a long time. This is notable not just for the solo acoustic format—other concerts from this time he did like that have been available for a while—but also for some unconventional song selections. Those include “Love in Mind,” “Dance Dance Dance,” and “Journey Through the Past”, along with a helping of familiar classics (“Heart of Gold,” “Old Man,” “A Man Needs a Maid,” “Don’t Let It Bring Me Down”), and many of the songs were unavailable on record at the time. The audio is also on a separate CD on the box, if you just want to hear the music. A 56-page hardback booklet has a good essay by longtime Young archivist/photographer Joel Bernstein, as well as a good number of photos from the period.

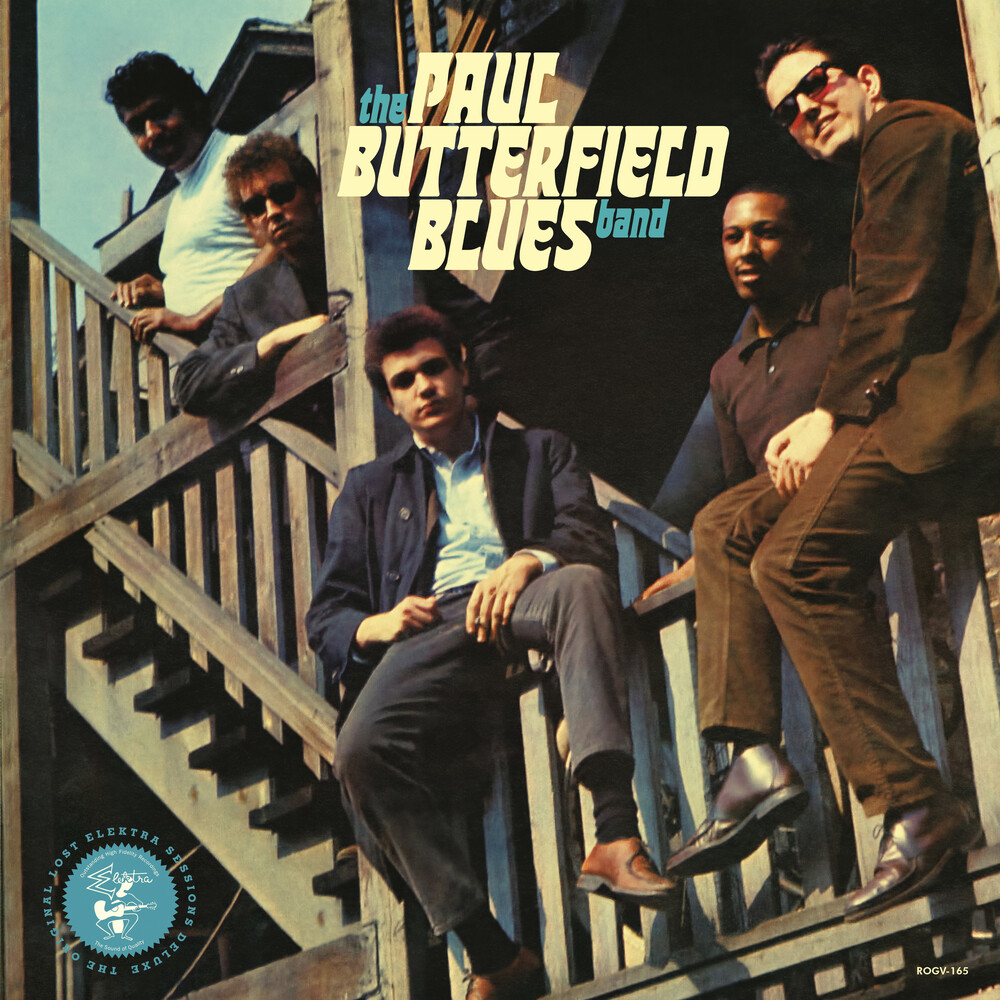

5. The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, The Original Lost Elektra Sessions Deluxe (Run Out Groove). To try to summarize a complicated back story quickly, before the Paul Butterfield Blues Band recorded their 1965 self-titled debut LP, they recorded an unreleased album, or enough for an unreleased album and then some. Producer Paul Rothchild thought he and the band could do better, so they started over and recorded the self-titled album, redoing some of the same songs, adding some others, and failing to revisit some of the tunes from the original sessions. Five tracks from the first attempt at the album did appear on Elektra’s 1966 various-artists compilation What’s Shakin’, and another, the first version of “Born in Chicago,” on the Elektra sampler Folksong ’65. Nineteen tracks recorded for the aborted first album were compiled on the 1995 release The Original Lost Elektra Sessions. What’s Shakin’ has been on CD, and the Folksong ’65 version of “Born in Chicago” made it to CD with 1997’s An Anthology: The Elektra Years. That seemed to be the end of this story.

But no, since this triple-LP vinyl June 2022 Record Store Day release expands the document of the mid-‘60s sessions that were unissued at the time quite a bit. The first three of the six sides have all nineteen tracks from the 1995 The Original Lost Elektra Sessions, making their vinyl debut, if that’s important to you. Of greater importance, the final three sides present previously unreleased material, mostly though not all from the sessions for the original pass at an LP. Yes, some of these are alternate takes or unedited/extended versions. But there are also songs that were previously unavailable in studio versions by the mid-‘60s Butterfield group, including a demo of Percy Mayfield’s “Memory Pain”; the slow instrumental jam “Blues for Ruth”; Otis Rush’s “Keep on Lovin’ Me Baby”; and the moody “Danger Zone,” also written by Mayfield, and recorded in the early 1960s by Ray Charles.

Most notable of all is the previously unreleased seven-and-a-half-minute instrumental “Love Song,” which has a similar rhythm to their great classic instrumental title track of their second LP in 1966, East-West. While the liner notes refer to this as an early version of that song, in fact the melody isn’t that similar, though it has a related jazzy offbeat feel that makes it conceivable it evolved into “East West” over time. This and “Danger Zone” were on a reel labeled “third album demos,” which would have made them postdate East West, though annotator Brett Milano writes that “Love Song” “was clearly demoed for [the] second album rather than the third.”

Could this sprawling, expensive package have been done better? Maybe recording session dates, if known, even generally, could have been more clearly noted, especially as not all of these are from the initial sessions intended for the debut LP. The availability of the unissued tracks on a separate CD would certainly be a money-saver for those not inclined to spend $60 or so on this triple-disc vinyl edition. But overall it’s well done, with decent liner notes and a full-color mid-‘60s picture of the band that doesn’t duplicate other commercial releases. Of more importance, the actual music showcases a band who were the best white (or majority white, anyway) US blues-rock outfit of their time. They had a lean and hard-hitting sound, even if their instrumental chops (especially Mike Bloomfield and Elvin Bishop on guitars, and Butterfield on harmonica) outstrip Butterfield’s adequate vocal abilities. It’s not as good as their actual official debut LP or more adventurous signature follow-up East-West, which went into rock and psychedelia on some tracks. But on the whole, it’s not far below the debut LP’s standard for tough blues that can verge on blues-rock.

6. The Sons of Adam, Saturday’s Son: The Complete Recordings: 1964-1966 (High Moon). The Sons of Adam were one of the best mid-1960s Los Angeles groups not to make it big. They were also notable for including ace guitarist Randy Holden (later in the Other Half and Blue Cheer) and future Love drummer Michael Stuart, though those guys weren’t in the band by the time the last of their three singles came out. In terms of packaging, this compilation is near-ideal, with both sides of all three of their 1965-67 singles; three decent studio outtakes; eight previously unreleased songs, in good fidelity, from a live August 6, 1966 show at the Avalon in San Francisco; and both sides of the 1964-65 singles by Holden’s previous surf outfit, the Fender IV, as well as a couple Fender IV outtakes. Voluminous liner notes by Alec Palao have lots of material from first-hand interviews with members of the group and details about how everything was recorded. While the studio material has been previously available on a long-ago EP and Japanese compilation, this gets all of that together for the first time in better sound quality, plus of course the previously unheard Avalon performances.

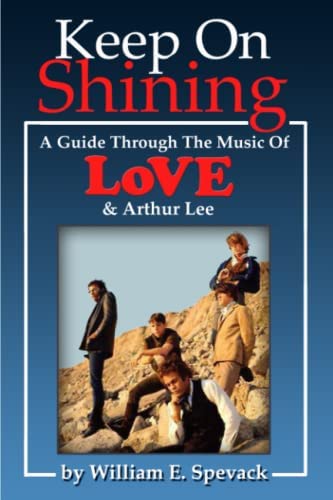

At their best, the Sons of Adam were on the cusp between raunchy garage and early psychedelia, paced by Holden, who had the best ferocious guitar sustain this side of Jeff Beck. They weren’t the most consistent act or most prolific generators of original material, however, which put them below the level of top competitors like Love. Only one of the eight Avalon tracks (“Saturday’s Son,” their best and best known single) was done in the studio, but that’s a mixed blessing, since the hitherto-unheard original compositions weren’t as good as their best singles, and the covers of “Evil Hearted You” and “Gloria” not so hot. The post-Holden-Stuart single “Feathered Fish” is here, fortunately, and will be of special interest to Love fans as it features a good Arthur Lee composition Love never put it on their own discs. Good too is the B-side, “Baby Show the World,” a raunchy blues-rock-psychedelic number with some fierce guitar and bass. The Fender IV sides might not be as cutting-edge as the Sons of Adam tracks, but have some great wild surf guitar by Holden on the instrumental “Mar Gaya,” as well as a fine bisection of surf and Merseybeat on the vocal offering “You Better Tell Me Now.”

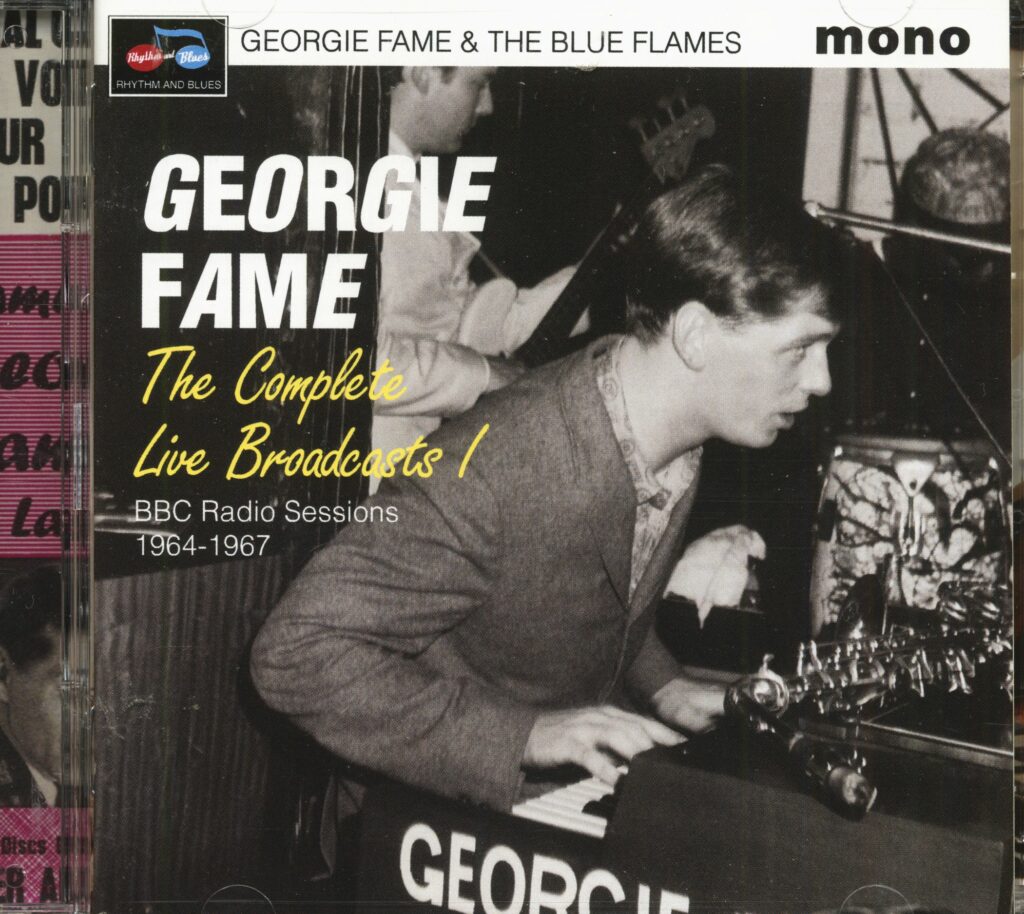

7. Georgie Fame, The Complete Live Broadcasts 2 (Rhythm and Blues). Like part 1 (released in 2021; see review in 2021 section below), this is a two-CD compilation of radio and TV sessions from the mid-1960s, these spanning early 1964 to late 1965. It might be a little less exciting overall than volume one, with occasional lower (though not bad) sound quality, and failing to include a few of his slightly later UK hits. Still, it’s generally a pleasing collection in which his enthusiasm and band arrangements for his distinctive blend of soul, blues, pop, jazz, and rock can’t be faulted. Certainly the diverse set reflects his wide-ranging and eclectic repertoire, though many of the songs are offered in multiple versions—four of “Let the Sunshine In.” If yet four more versions of “Yeh Yeh” after three on volume one might seem a lot, he never gets tired of performing that big hit with zest. Note that “You’re Breaking My Heart” has a guest lead vocal by Long John Baldry, though otherwise it’s all Fame on lead.

True, Fame versions of all of these songs have been previously available, whether as part of his actual 1960s releases or other versions, including live performances circulated many years later. These two collections of broadcasts, however, allow bulk hearing in a couple concentrated groupings, instead of spread around archival discs that are sometimes obscure and expensive. It’s also amazing there’s so much non-studio Fame from this period, making one wish there was as much from some other British Invasion acts, though that’s another issue entirely.

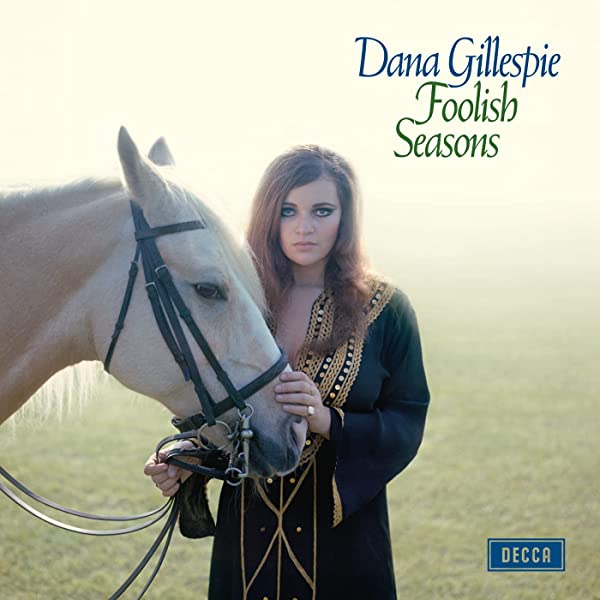

8. Dana Gillespie, Foolish Seasons (Decca). Gillespie’s 1968 debut album might be better known now than it was back then, when it sold hardly anything. In part that’s because it was inexplicably issued only in the US, though Gillespie’s British and was signed to a UK label. Although she’s most known for her 1970s association with David Bowie and his management, and for many far bluesier records she did after that, Foolish Seasons is much different in tone. Broadly speaking, it’s kind of like some of Marianne Faithfull’s artier and more ambitious ‘60s recordings in its blend of orchestrated pop, folk, and rock. Unlike Faithfull (at the time), Gillespie wrote some of her songs, though they’re in the minority on this album, which also has compositions by Donovan, Richard Fariña, Billy Nichols, and poppier material by writers like Jeff Barry, Andy Kim, and her producer Wayne Bickerton. She also rocks out somewhat more than Faithfull did in the ‘60s, though not that hard, and this is in some ways more adventurous than Faithfull’s early stuff.

This isn’t a top-tier record, even within its limited genre, but it’s an enjoyable and imaginatively produced/arranged set. It hasn’t been that rare since it was reissued on CD in 2006, but makes this list by virtue of having a 2022 vinyl Record Store Day release. That in itself wouldn’t put it here, but the new LP edition adds two previously unreleased songs from the sessions,. Both were written by Gillespie and both are up to the general caliber of the rest of the album, though the moodier “Come to My Arms” is better than the more uptempo “Goin’ Round in Circles.” The front and back covers of the gatefold sleeve have different full-color photos from the same session that generated the pictures used on the original LP. And Gillespie wrote new historical liner notes for the inner gatefold. Will that make it worth Record Store Day prices if you have a previous edition? Maybe not, but at least the extras are relatively significant as these things go, and the package well done.

9. Norma Tanega, I’m the Sky: Studio and Demo Recordings, 1964-1971 (Anthology). For me, singer-songwriter Tanega is one of numerous artists who falls between the major and minor: overrated by a cult following and not nearly as significant as the best talents in her field from the era, but too interesting and creative to dismiss as an also-ran. Remembered by the general public almost exclusively for her whimsical 1966 hit “Walkin’ My Cat Named Dog,” she had a couple full albums of mildly eccentric/eclectic pop-folk-rock, delivered in a voice that could sound like a wayward Carole King. This double CD includes much (but by no means all) of the material from her 1966 album Walkin’ My Cat Named Dog and her more obscure 1971 LP I Don’t Think It Will Hurt If You Smile, along with thirteen previously unreleased demos and a couple tracks from an unreleased 1969 Capitol album that would have been titled Snow Cycles.

If not brilliant, Tanega is wide-ranging and unpredictable, drawing from dulcimer folk, gospel, Brill Building pop orchestration, and other elements outside of the common singer-songwriter approach. Her outlook can vary from sunny romance to quirky humor. But only occasionally do the melodies and spirit really soar, as on the buoyant “I’m the Sky,” the almost funky Brill Building pop of “A Street That Rhymes at 6 AM,” and “Jubilation,” all from the first album. Most of the previously unreleased demos, most of songs not on her 1966 and 1971 LPs, are grouped together on the second disc, and while they’re generally winsome, they tend to blur together, as singer-songwriter demos often do when they’re not graced by studio elaboration/orchestration. The clear highlight, the ebullient “What More in This World Could Anyone Be Living For,” is a sparer version of song that appeared on I Don’t Think It Will Hurt If You Smile (the LP version is on disc one). Folky with multi-tracked vocals, it’s far superior to the odd sluggish LP arrangement, with burbling wah-wah funk guitar.

Tanega didn’t seem to give many interviews or be very forthcoming in those, but the liner notes in the 28-page booklet do about as well as they can with the info available. The package can be criticized, however, for switching back and forth between tracks on Walkin’ My Cat Named Dog and I Don’t Think It Will Hurt If You Smile on disc one, instead of presenting them in a more logical chronological order. And since the total running time is only 85 minutes, there could easily have been room for all of the tracks from both LPs and the two non-LP tracks from 1966-67 singles, and maybe more from Snow Cycles too. Real Gone’s 2021 reissue of Walkin’ My Cat Named Dog (for which I wrote, in full disclosure, the liner notes) has both non-LP tracks, but I Don’t Think It Will Hurt If You Smile hasn’t been reissued on CD. And while it might be a small point, there are no details about the previously unissued demos except the date range. Is it so much to ask of reissues in general to at least note in the annotation that nothing is known about the specific dates and/or sources of such material, instead of just putting it out there with little or no elaboration?

10. Merrell Fankhauser, Goin’ Round in My Mind: The Merrell Fankhauser Anthology 1964-1979 (Grapefruit). When many of us were just discovering Merrell Fankhauser via reissues both legit and pirate in the 1980s, the very thought of a six-disc box of his prime work would have seemed like 21st century fantasy. Now that the 21st century is well underway, that six-disc box is here. It’s entered around the three albums that cemented one of the strongest cult followings of any ‘60s artist who never approached significant commercial success or (at the time) critical recognition.

The wealth of extra material doesn’t approach the high, if quirky, quality of those three late-‘60s/early-‘70s LPs. This set would have ranked considerably higher on this list if all of the material hadn’t been available for quite a few years on various previous reissues, meaning many apt to be interested in this set will already have much of it. But it rounds out the picture of the SoCal singer-songwriter-guitarist’s improbable journey from folk-rock and psychedelia through Captain Beefheart-linked late bluesy psych.

The least familiar cuts here are on disc one, dating from 1964 and 1965, and have barely a glimmer of the potential he’d realize just a year or two later. Largely unreleased at the time (though five of the nineteen tracks appeared on rare 45s), these feature Fankhauser as leader of Merrell and the Exiles, who at various times included future Beefhearters Jeff Cotton (on guitar) and John French (on drums). Operating (like Beefheart) way north of L.A. in Lancaster, they were a just slightly above-average combo of the time, whose heavily Mersey-influenced sound still had some echoes of the surf era and earlier icons like Del Shannon and Buddy Holly. None of the numbers stand out much, though “Send Me Your Love” is a decent catchy garage-Merseybeat blend, and “Run Baby Run” has a somewhat tougher and bluesier feel. (Note that nothing is here by Fankhauser’s earlier surf group, the Impacts, who put out the Wipe Out! LP.)

There was a huge change, however, and much for the better, with the self-titled album by the Fankahuser-led Fapardokly (given a circa February 1968 date here, though it’s previously been reported as a 1967 release). Although it’s a haphazard mix of ca. 1966-67 sessions and 1964-1967 singles, it has some gorgeous if goofy prime L.A.-style harmony and chiming guitar-driven folk-rock (“Lila” and a somewhat bitter comment on Hollywood’s cut-throat competition in “The Music Scene”). There’s also “Eight Miles High”-like psych (“Gone to Pot”), whimsically weird acid-folk-rock (“Mr. Clock” and “Glass Chandelier”), a folk-rock-Zombies blend (“Tomorrow’s Girl”), and the gleefully commercial (in the best sense) “When I Get Home.” The 1964-65 singles boast incongruous if well-done pastiches of Buddy Holly, Ricky Nelson, and Roy Orbison, yet somehow add to the likably eccentric and eclectic program, topped by “Supermarket,” which I’ve likened to a psychedelic airline commercial. Fankhauser’s likable clear, high vocals are a constant throughout, though the three at-the-time-unissued 1966-67 bonus cuts on disc two aren’t at the same level.

He went for a more consistent pop-psych sound on late ‘68’s Things, credited to Merrell Fankhauser and HMS Bounty. While it’s not as thrillingly odd-yet-accessible as Fapardokly, it projects more of the good-natured warmth at which he could excel. Some songs (like the title track) approach straightforward L.A. late-‘60s pop-rock; some surprising bluesy hard rock-psych tension, however, makes its way into “Drivin’ Sideways (On a One Way Street).” But it’s at its best at its most psychedelic, like “A Visit with Ashiya,” which recalls Donovan’s Indian-informed work at its best; the wistful “Ice Cube Island,” more proof that Fankhauser couldn’t seem to avoid some oddball lyrics even when he was obviously aiming for the most melodically accessible vibe he could; and the quietly sinister “Madame Silky.” Bonus non-LP cuts from flop 1969 singles include the surprisingly tough slide blues guitar-powered “I’m Flying Home”; “Tampa Run,” which is strangely upbeat considering its drug smuggling-inspired lyric; and a just plain weird mariachi arrangement of Fred Neil’s “Everybody’s Talkin’.”

Fankhauser reunited with Jeff Cotton for 1971’s self-titled MU, the name inspired by a supposed lost continent. In another surprising shift, the music at times sounds like a far more accessible Captain Beefheart, whose clutches Cotton had just escaped. That’s especially evident on the opening Cotton-composed “Ain’t No Blues,” though more often it’s a little like a spacier take on the kind of psych generated by Grateful Dead-like outfits, with occasional spooky mournful howling backup vocals and jungle-like percussion. “Look at the sun, look at the moon, brother we are one” date some of the more utopian sentiments to the early-‘70s, though this remains far and away the favorite of Fankhauser’s albums among those who favor this kind of thing over pop-psych-folk-rock. Three bonus cuts from 1972-73 singles don’t have quite the same level of mystic-tinged strangeness.

Those foretell Fankhauser’s general drift into mellower territory in the early-to-mid-‘70s, in tune with the times and perhaps influenced by his relocation to Maui. MU’s The Last Album, featuring tracks recorded in early 1974 but not issued until quite a few years later, has a drowsy island feel that’s not as engaging as the more energetic ’71 LP, though Cotton was still aboard. Fankhauser went solo, and on a more straightforward singer-songwriter path, on 1976’s The Maui Album. By this time his sound had moved more toward new age-flavored adult contemporary music than vintage folk-rock, though he could summon spare and airy odes like “I Saw Your Photograph” and hippyish celebrations like “Make a Joyful Noise.” Five bonus tracks from 1975-77 were not released at the time, the set finishing with his 1979 single “Calling from a Star.”

The 36-page booklet has a wealth of photos, info, and Fankhauser quotes, as well as clarifying some of the more mysterious corners of his zigzagging discography. (For instance, it turns out that Don Aldridge, who wasn’t even in Fapardokly, sings lead on “Mr. Clock” and “Glass Chandelier.”) It’s too bad you literally need a magnifying glass to comfortably read the brief notes on the back of the CD cover of disc one. But as you’d expect from the Grapefruit label, on the whole this box is an expertly assembled and packaged compilation of Fankhauser’s prime decade or so. His evolution was among the most extreme of any ‘60s cult rocker, and sometimes among the most adventurously listenable. (A slightly edited version of this review will appear in a future issue of Ugly Things magazine.)

11. Duffy Power, Live at the BBC Plus Other Innovations (Repertoire). Although nineteen of these tracks came out on Sky Blues back in 2002, the first two discs of this three-CD set form a much bigger overview of this British blues-rock-folk-jazz singer’s BBC recordings. There are a total of 41 BBC tracks from 1963-1997 (along with three brief radio interviews), all but seven from 1963-1973. Power’s best recordings by far were the ones he did in the studio in the mid-1960s that came out in 1971 on the LP Innovations, itself just reissued with eleven bonus tracks (see review #3 on this list). This compilation isn’t on par with those, or with the folkier ones on his Duffy Power LP of 1969 material, and the sound quality varies from good to muffled but acceptable, depending on the source. Note that a few seconds near the beginning of one of the 1963 versions of “I Saw Her Standing There” seem abruptly edited out, hopefully as a result of an imperfection in the surviving tape, rather than a manufacturing defect.

But that’s how BBC compilations usually are; they’re extras to be savored by fans who want more than main dish. These radio performances fulfill that purpose well, including some originals and covers unavailable in studio versions. Some of those are just okay overdone rock’n’roll/R&B standards like “I Got a Woman,” “Lawdy Miss Clawdy,” and “Roll Over Beethoven,” but usually the repertoire’s fairly off the beaten track. The backing varies from full band, including the Graham Bond Organization with John McLaughlin on a half-dozen 1963 items, to much sparer solo and duet outings. Other sidemen of note include Alexis Korner, Danny Thompson, and Terry Cox on a couple 1968 cuts, and Rod Argent on piano on five numbers from a 1971 session.

While most of this falls into the “good” rather than “striking” category, some highlights include a 1965 take on Little Walter’s “Everything’s Gonna Be Alright”; the lilting pop-blues original “La La Song,” from 1968; an intense solo performance of the kind of low-key blues-folk-jazz at which he could sometimes excel, “The River”; and a solo acoustic guitar and vocal run through “That’s All Right Mama” (1970). Some of the backing on the four-song 1973 session’s too heavy to ideally suit Duffy’s more subtle style, but the ones on which his singing and guitar are backed only by Argent’s piano make for a nice change of pace from his usual approach. Their arrangement of “Little Boy Blue” isn’t nearly as good as the explosive full-band studio one from the mid-‘60s, but again, at least it’s notably different. The moody, minor-key ballad “Where Am I?,” which he’d done on an obscure single also recorded the year (1964) this BBC version was laid down, is the poppiest thing here. It’s also the best, and far better sung—and more simply and appropriately arranged—than the orchestrated studio version, though probably not the kind of material he was most passionate about.

Disc three has largely unreleased studio recordings from 1995-2001, and while it’s a cliché to note how long-after-the-prime efforts are usually of limited interest, that’s true of these (and the 1997 BBC recordings on disc two). Power was still in pretty good voice, but the backing leaned more toward polite jazz than it had in his best decade. Peter Brown wrote part of the liner notes, and while I like and respect his contributions to the British music scene in which he was a peer of Power, few would agree with his opinion, as voiced in these notes, that Duffy’s version of “I Saw Her Standing There” was better than the Beatles’ original. I don’t, though Power did an interesting more soul-rock arrangement with Bond’s band as backup, heard on an early 1963 single (reissued elsewhere) and two 1963 BBC versions here, with Jack Bruce on bass, Ginger Baker on drums, and McLaughlin on guitar. There’s also a solo guitar-and-vocal rendition from 1971 that’s definitely not as good as the ones from 1963, let alone the one by the Beatles.

12. Lou Reed, Words & Music, May 1965 (Light in the Attic). Why isn’t this collection of previously unreleased, circa spring 1965 demos higher on the list, considering I wrote a huge book on the Velvet Underground? Its historical importance is massive and undeniable. But it’s not nearly as great as what he and John Cale (who sings some harmony on these demos, and sings lead and plays a bit of percussion on one) would be doing with the Velvet Underground about a year later. It’s also surprisingly folky, and even sometimes has a bit of a hillbilly twang. This can also be said of the nearly 80 minutes of July 1965 demos (also including Velvet Underground guitarist Sterling Morrison) that came out on the 1995 Peel Slowly and See box set. But even those July 1965 demos were considerably more polished, relatively speaking, than these earlier efforts, probably taped shortly before he mailed the tapes to himself as proof of copyright on May 11, 1965.

The demos on this collection only hint at the brilliance of the Velvets, even though they include a few early versions—in fact, the earliest versions—of some of their classics. The arrangements and execution are kind of bare-bones and occasionally a little ragged, even for “Heroin” and “I’m Waiting for the Man.” Some harmonica makes it sound closer to tail-end folk revival music than anything the VU recorded. A big surprise is a performance of “Pale Blue Eyes,” not released by the Velvet Underground until their third album in early 1969, though it’s known the band were playing it live as early as mid-1966. This has some verses with lyrics that didn’t make it on the official version, although they’re not as good.

“Pale Blue Eyes” and “Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams,” the latter with Cale on lead vocals, are the highlights of this release. While the Velvets didn’t put the latter song on their albums (although it’s on Nico’s 1967 Chelsea Girl LP), “Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams” is the track that most clearly anticipates the much different, and much more innovative, sound of the Velvet Underground in its spooky, slightly menacing atmosphere and haunting, literary lyrics. It sounds a bit like a Welsh folk tune in this arrangement, as indeed it does on Peel Slowly and See.

There are a half dozen original songs the Velvets wouldn’t do, but they’re rather threadbare and unimpressive, whether a near-English trad folk satire (“Buttercup Song”) or vague soul-pop-rock throwaway vibe (“Buzz Buzz Buzz”). None of them sound like promising compositions that could flower with more development. They’re more like the kind of thing that almost every record company or music business figure would reject as both uncommercial and unmemorable. They’re interesting nonetheless for revealing just how enormous a distance Reed and Cale had to cover before setting the foundations for the Velvet Underground sound, and how quickly that did occur, since most of their first album was recorded in spring 1966. A few extras—a 1958 generic early rock’n’roll rehearsal track and home 1963-64 recordings that reveal Reed’s surprising bent for folk at the time (including covers of “Michael Row the Boat Ashore” and Bob Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice, “It’s All Right”)—are yet more purely of historical interest.

Note, incidentally, that none of the 1965 tracks are the same as the unreleased ones (including two versions of “Heroin”) Reed and/or Cale recorded at the studios of Pickwick Records on May 11, 1965. As the detailed liner notes explain, that’s an entirely different tape/performance, none of which is included on this compilation.

13. Jimi Hendrix, Los Angeles Forum April 26, 1969 (Experience Hendrix/Legacy). There’s such a constant flow of archival Hendrix releases that it’s almost like he’s a contemporary artist. Even as someone who keeps up with these, it is getting to the point where they’re not as essential as they used to be. This is from the final months of the original Experience, and it’s a looser, more improvisational-oriented set than most of what they’d done. That’s not for the better, in my view—some of the soloing goes on way too long, with “Spanish Castle Magic,” a concise tune when it was on Axis: Bold As Love, lasting twelve minutes. The opening “Tax Free” would have been unfamiliar to almost all of the audience (and still isn’t too familiar today), but it’s a pretty sprawling, undisciplined workout without much in the way of hooks and melody. While three albums were under his belt at this point, there isn’t much in the way songs uncommon to concert recordings, and a couple of overly familiar staples in “Foxey Lady” and “Purple Haze.”

Certainly there are fans who like the more unreined side of Jimi, and his guitar work is always incendiary, if unfocused here when compared to many of his other recordings. And you do get near-maximum running time with 79-plus minutes, including versions of “Red House” and “Voodoo Child,” and less commonplace items with “I Don’t Live Today” and a cover of “Sunshine of Your Love.” There are also decent historical notes, but it’s not among the best Hendrix live sets, which are now so numerous that this is more for the dedicated fan than the average enthusiastic fan.

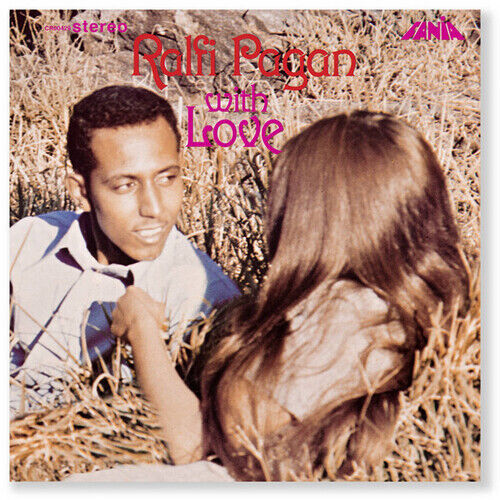

14. Ralfi Pagan, With Love (Craft). Pagan was one of the more successful artists on the Fania label, which targeted Spanish-speaking (and especially Puerto Rican) residents of the US in the 1960s with Latin jazz and boogaloo, a mixture of Latin, jazz, and soul. With a high, sensuous voice that could almost be mistaken for a woman’s, he was also one of the more mainstream Fania acts, with some of his sides in the early-‘70s sweet soul bag. He could also sing salsa, and both salsa and soul are on this vinyl reissue of his 1971 LP. Side one is by far the more salsa-flavored, all but one of the songs being in Spanish. Side two is pretty straight soul, including his Top Forty R&B cover of Bread’s “Make It With You.”

Pagan was more distinctive as a soul singer than a salsa one, at least to listeners like me who are more soul than salsa fans in general. “Make It With You” actually isn’t the best of the soul tracks, that honor belonging to “To Say I Love You,” with its aching catchy descending melody in the chorus. That’s enough to propel it to a position on this list. Much of the rest of side two is closer to decent but not as memorable period ‘70s sweet soul ballads and midtempo romantic tunes. It’s not far from some Philadelphia soul of the time in feel, and though the vintage liner notes call them “low-down soul boleros,” they’re more like low-key, immaculately produced soul songs – not that there’s anything wrong with that.

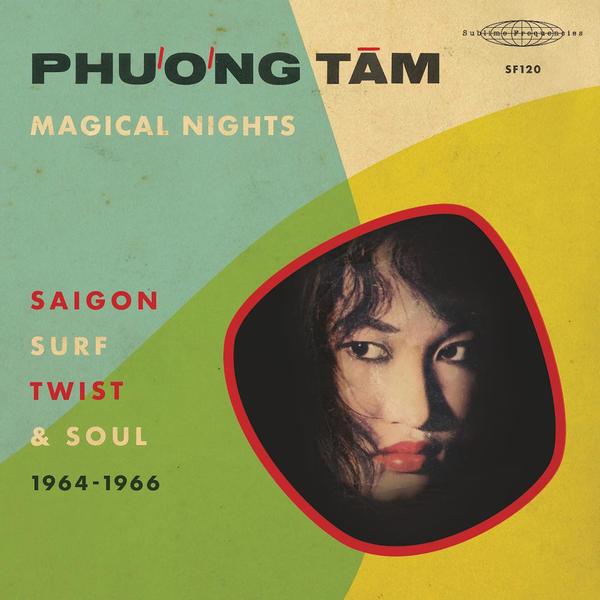

15. Phuong Tam, Magical Nights: Saigon Surf Twist & Soul 1964-1966 (Sublime Frequencies). It’s kind of amazing this 25-song compilation even exists, since Vietnamese popular music recordings from this era are hard to find, and those that are retrieved are often not in good condition. Through the industriousness of Sublime Frequencies, this extensive collection of this woman Vietnamese pop singer has been assembled. It might be of more historical interest than outstanding musical quality, though she was a decent vocalist. Much but not all of it’s rock, usually in a generic early-‘60s style, though there are often haunting idiosyncratic Vietnamese elements to the melodies and arrangements.

There’s considerable Western twist and instrumental rock influences, and some surf (particularly in the guitar tones, which likely owe something to the Shadows too), though not much British Invasion (despite the 1964-66 dates) and less soul, at least as Western audiences usually perceive the term. At times this approaches torch song, jazz, or even novelty military-beat territory, though it’s rock more often than not. The recording quality and instrumental execution can be on the crude side, though that adds to its exotic air, at least in comparison to commonly available rock from non-Asian countries. Tam can really belt it out with some raw throaty vocals at times, though she opts for a smoother approach at others. This reasonably engaging, though not brilliant, glimpse into a sort of mash-up early ‘60s-styled rock unfamiliar to most of the global audience comes with informative notes from her daughter and compiler Mark Gergis, the booklet also including a wealth of vintage photos and memorabilia.

Honorable Mention:

Bert Jansch, At the BBC (Earth Recordings). This eight-CD box of the great Scottish folk guitarist’s BBC recordings gets only an honorable mention since it’s only the early material that interests me a lot. While the set spans 1966-2009, only 45 minutes predate 1971—after which there’s a significant gap, picking up in 1977 in a session that features Mary Hopkin as singer. Those 45 minutes from the early years have variable fidelity ranging from fine and clear to iffy, and the performances aren’t up to the best he did on his numerous solo records (and ones in which he played as part of Pentangle). But they offer superb folk guitar with a generous blues influence, as well as engaging emotional vocals, even if his singing was never destined to be as notable as his instrumental work.

Four of the tracks are duets between him and fellow Pentangle guitarist John Renbourn, and in fact some of the tracks are solo spots from broadcasts largely featuring Pentangle. A few of the songs aren’t found on other releases, including the original “Whiskey Man” (not the Who song, from 1966); another original, ‘Speak of the Devil” (1970); and the traditional folk number “Thames Lighterman” (1968). The package is excellent, with thorough liner notes, but not enough to make this expensive set worthwhile if you likewise aren’t too interested in his post-mid-‘70s material.

The following reissues came out in 2021, but I didn’t hear them until 2022:

1. Georgie Fame, The Complete Live Broadcasts 1 (Rhythm and Blues). Although some mid-‘60s BBC recordings by Fame were issued on box set The Whole World’s Shaking, this offers a much more comprehensive selection. The two-CD set has 47 tracks he did for the BBC between 1964 and 1967, along with numerous brief interview snippets. With so much material, it’s a little surprising that just a couple of the songs, to my knowledge, don’t appear in any form on other Fame releases, unless you want to count an abridged vinyl collection on the same label (Rhythm & Blues At the BBC 1965). These are Ray Charles’s’ “Tell the World About You” and, more impressively, Booker T. & the MG’s’ instrumental “Boot-leg,” on which Fame and his band the Blue Flames really cook. Note too that three songs are actually from a 1966 Lulu session on which the Blue Flames backed the singer, and those were previously available on the Lulu BBC session collection Live on Air 1965-1969.

Otherwise this is in line with the usual BBC sessions of British Invasion notables from the mid-1960s: live-in-the-studio takes that often have a somewhat looser feel than the official versions. (And a guitar solo, though not a great one, on “Get on the Right Track, Baby” instead of a sax one.) There are some multiple versions of some of his more popular tunes—three apiece of “Yeh Yeh” and “Point of No Return,” in fact—but there’s not too much repetition. The sound is fine and clear, and this wouldn’t rank below a good Fame mid-‘60s best-of collection for enjoyable swinging blues-soul-jazz-pop-rock. A pre-Jimi Hendrix Mitch Mitchell is on drums for some of these, most likely the sessions spanning December 1965 to June or October 1966, though the annotation isn’t too clear about this. Otherwise it’s packaged pretty well, with fairly comprehensive liner notes and a few photos.

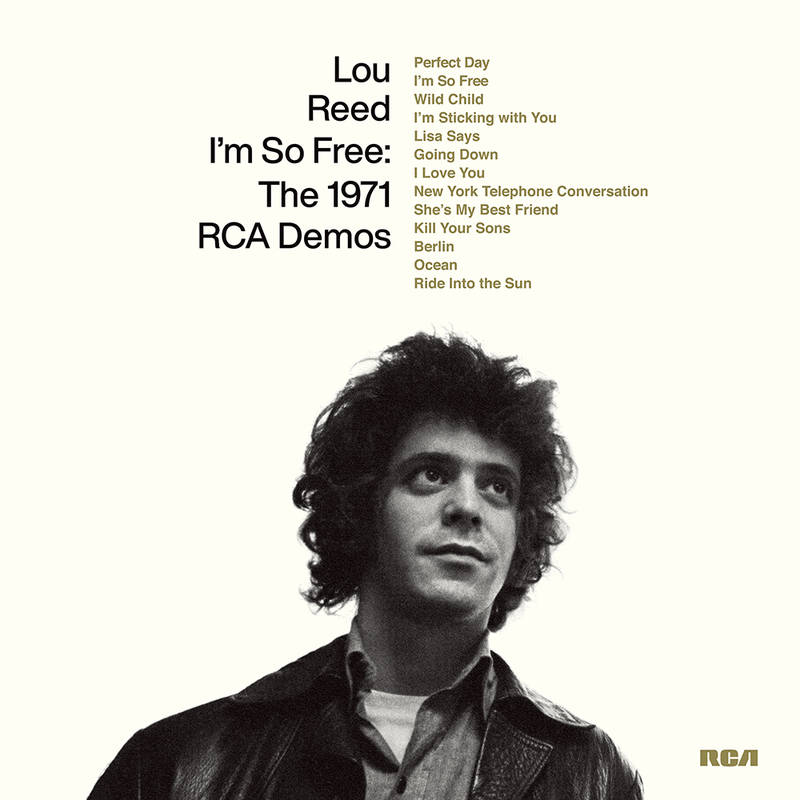

2. Lou Reed, I’m So Free: The 1971 RCA Demos (RCA/Sony). This was available so briefly in its full version that you might have missed it, or at least missed it when it was on iTunes for a couple days, as I did. Here’s the story: around the very end of 1971 or the very beginning of 1972, Lou Reed cut seventeen solo demos in an unknown London studio, accompanying himself on acoustic guitar. These include versions of all ten of the songs that were used on the self-titled solo debut album he recorded in London in January 1972, as well as a few (“Perfect Day,” “I’m So Free,” “Hanging ‘Round,” and “New York Conversation”) held over for his follow-up, Transformer. Rounding out the demos are “Kill Your Sons” and the Velvet Underground leftovers “She’s My Best Friend” and “I’m Sticking With You.”

In late December 2021, all of the material was very briefly made available by RCA/Sony Music through iTunes to extend its copyright before its fiftieth anniversary was reached, though it was removed just a couple days later. Most, but not all, of the tracks came out on a vinyl Record Store Day LP in 2022. Although the title, I’m So Free: The 1971 RCA Demos, gives these a 1971 date, they seem more likely to have been done in early January 1972, right before or as the sessions for Reed’s first solo LP started in London. In excellent quality, these are fine, heartfelt performances that are more forceful and edgy than the far more slickly produced tracks used on his debut. Although the similarity in the plain acoustic guitar backing can become a little wearing over the course of the 56 minutes, it would make a fine bonus disc for a more widely available expanded version of his self-titled debut Lou Reed album.

The demos of “Hangin’ Around” and “Perfect Day,” incidentally, are the same ones that were added to the 30th anniversary edition of Transformer as bonus tracks. “Perfect Day” is a little different, however, as a brief half-minute aborted take one is also included, ending with a curse and a laugh after a stumble. Reed then promises, “I’ll leave out the tricky guitar bits, I think.” The version of “Ocean” is the same superb, dramatic performance as one that had been bootlegged for many years without details as to its source, finding its first official release here. However, as with “Perfect Day,” it’s preceded by a brief take 1, which combines some vague studio chatter with a mere fifteen seconds of instrumental guitar strumming before it’s abandoned.

Richard Robinson, who produced Reed’s debut LP, is likely present for most or all of the demos, as Reed gives an “okay Richard” shout-out near the end of “I Love You.” “I’m Sticking with You,” “Going Down,” “Ride Into the Sun,” “Hangin’ Around,” and “Love Makes You Feel” are all identified as “take 2,” leaving open the question as to whether other takes exist. These might simply be brief incomplete first takes, like the ones of “Perfect Day” and “Ocean” that did make the copyright extension release.

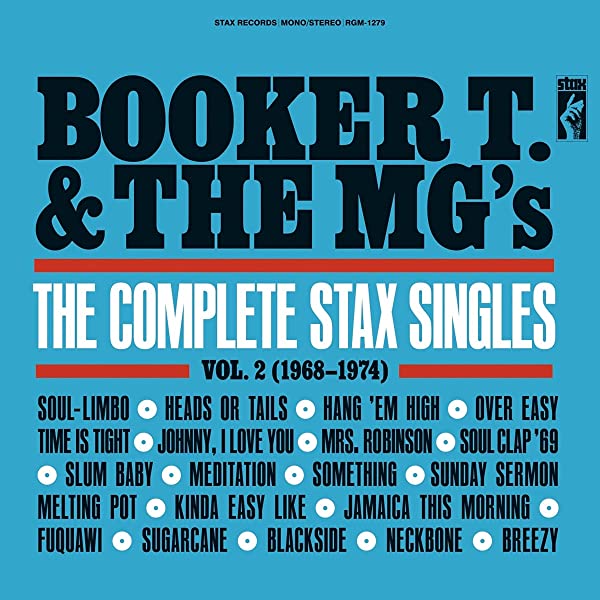

3. Booker T. & the MG’s, The Complete Stax Singles Vol. 2 (1968-1974) (Real Gone). The later years of Booker T. & the MG’s were kind of odd, as their two 1969 Top Ten singles, “Hang ‘Em High” and “Time Is Tight,” were as popular and good as anything they recorded, except maybe “Green Onions.” Overall, however, they weren’t as creative or consistent as they had been in their pre-1968 period. Some of the cuts are rather routine and laidback, and the instrumental versions of “Mrs. Robinson” and “Something” don’t rework those familiar monster hits in interesting ways, though they actually did reach the charts, “Mrs. Robinson” entering the Top Forty. Five of the post-1970 tracks were billed to “The M.G.’s,” and as you’d expect suffer from the absence of Booker T. Jones.

This is still pretty pleasant groove music, often decorated by Steve Cropper’s always sharp bluesy guitar. There’s a general shortage of killer riffs, however (“Hang ‘Em High” and “Time Is Tight” excepted). And Jones’s nicely melancholy composition “Meditation” certainly seems to owe a lot to “Summertime,” though he might have underestimated “Hang in High”’s B-side, the moody and jazzy “Over Easy,” with Booker on piano instead of his usual organ. Although it’s one of the best little known tracks, he called it “me and my cohorts at our most pretentious” in his autobiography, adding, “the song is so un-Memphis-like, so un-MG’s-like. It sounds as if it was recorded at some swank Chicago nightclub on the South Side.”

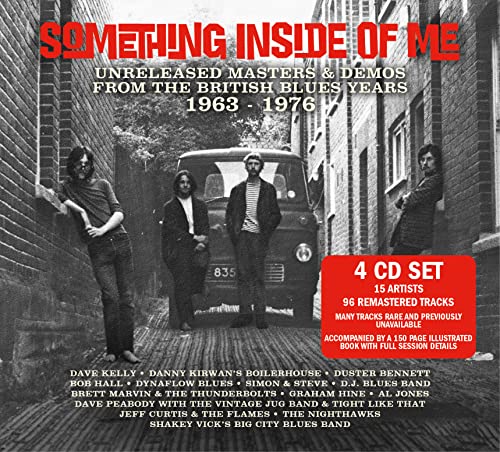

4. Various Artists, Something Inside of Me: Unreleased Masters & Demos from the British Blues Years 1963-1976 (Wienerworld). It’s not so obvious from the song list, but this four-CD, 96-track compilation includes five previously unreleased cuts of particular historical note. These are the five by Boilerhouse, who included a teenage Danny Kirwan shortly before he joined Fleetwood Mac. A few of the other artists will be known to serious British blues aficionados, including one-man band Duster Bennett; Dave Kelly; and Al Jones, though Jones is more known for less blues-oriented mild folk-rock he released in the early 1970s. Maybe throw in Brett Marvin & the Thunderbolts too, but otherwise these names will draw blanks even with those interested enough in this genre to pursue rarities, like Dynaflow Blues; the D.J. Blues Band; the Nighthawks (unrelated to the far more famous US group of the same name); Tight Like That; Jeff Curtis & the Flames; and Shakey Vick’s Big City Blues Band, to name a few.

Certainly this isn’t nearly on the level of notable multi-disc British blues compilations like Sire’s History of British Blues back in 1973, or Grapefruit’s Crawling Up a Hill: A Journey Through the British Blues Boom 1966-1971 just a couple years ago. With a couple exceptions, these are more like the foot soldiers or, to be blunter, also-rans that populate the back ranks of any genre in force. Most interesting by far, if as much or more for historical interest than the quality of the music, are the five songs by Boilerhouse, recorded in summer 1968 very shortly before Kirwan joined Fleetwood Mac. Elmore James’s “Something Inside of Me” would be redone by Fleetwood Mac, and the earlier version here isn’t too different in arrangement, with Kirwan’s talents obvious at this formative stage. The other Boilerhouse material isn’t as impressive, highlighted by an instrumental version of Otis Rush’s “All Your Love.” Note that there’s a brief skip on “Something Inside of Me” as the acetate from which it’s sourced is damaged, which is conscientiously explained in the liners, as are some other sonic deficiencies.

Some of the better other material is supplied by Duster Bennett, with seven July 1965 recordings (with a bit of percussion accompanying Bennett’s vocals/guitar/harmonica). These are highlighted by the brief off-kilter instrumental “Kimberly,” a refreshing break from the standard blues progressions dominating most of this anthology that sounds more like Davy Graham than straight blues. It’s too bad the 1968 acetate from which “Worried Mind” was taken is in rough shape, but it’s one of his more energetically satisfying performances. The D.J. Blues Band, at the earliest part of the period covered here with four November 1963 cuts, have an enjoyable sort of blues-rock-jazz crossover a bit reminiscent of some somewhat better known groups of the time making the crossover from jazz to more accessible blues-pop-rock, like the Mike Cotton Sound. While I’m not a big fan of Al Jones generally, some of his country blues-flavored outings (all from the early ‘70s) show more gutsy imagination and folk guitar dexterity than most of the other acts on this collection, particularly “Liza.”

There’s not as much so say about the numerous other artists and tracks on this compilation. Most of them aren’t bad and indeed often reasonably enjoyable while they’re playing, but don’t stick out either in terms of performance or material. Jeff Curtis and the Flames are really more like early British Invasion rock’n’roll than blues with their heavily Chuck Berry-flavored sound on their late-’63 efforts, not that it’s a bad thing. The Nighthawks (the most heavily represented act with eighteen tracks) and Brett Marvin & the Thunderbolts are pretty tight if pretty generic and unexceptional; the selections more inclined toward jug band, straight country blues, and piano blues can grate. So this can’t be recommended even to many average British blues fans, unless you’re a Fleetwood Mac completist. But if you do have a particular fanaticism for the first decade when the form was at its peak, it can still strike an acceptable chord, accompanied by a super-detailed 150-page booklet with plenty of period photos/graphics and session info.