On July 8, 2023, I interviewed Richard Morton Jack about his new outstanding biography Nick Drake: The Life at Blackwell’s book shop in Oxford, England. This is a transcript of our conversation.

JAMES ORTON (Blackwell’s): Thank you for joining us this afternoon, and a huge thank you to our musicians. Now we’re into the main event, which is Richie Unterberger discussing the new biography of Nick Drake by Richard Morton Jack. I spent the whole of yesterday reading it. It’s so thoroughly researched, and the love and respect you can feel Richard giving Nick throughout it is incredible – but obviously I’ll let Richard tell you about it. So please join me in giving a very warm welcome to Richie Unterberger and to Richard Morton Jack.

RU: I’m very happy to present this event with Richard, whom I’ve known for about twenty years. We’ve become good friends because of our mutual interest in the era of music in which Nick Drake operated, and I had the pleasure of reading the manuscript of his biography quite a bit before publication. I know some of you have read it already, and I urge those of you who haven’t to get a signed copy today.

I’ll be asking Richard how he came to conceive of a work that’s not just deeply researched, but also, I think just as importantly, has proper perspective on Nick Drake that demythologises a lot of the misperceptions that have arisen around this very talented but troubled artist. The amount of research that went into documenting this figure who, when he was alive, not much was known about, and who didn’t make himself known well to the public, is just amazing. Just a couple of examples. It has so frequently been reported that Nick Drake did just one interview. That is not true: Richard found the other one.

RMJ: Another one!

RU: Another one – which appeared in the most unlikely place, a teen-oriented magazine, and contained some useful information. Another example: contrary to what you might see online, there were many reviews of Nick Drake’s records when he was around, and Richard found one of Pink Moon in Penthouse magazine. Would you have ever thought to look in Penthouse?

Richard interviewed many of Nick’s surviving friends and associates, some of whom have never been on the record before, and they did a great deal to clarify Nick’s personality and musical achievements. My first question is, what did you most want to find out when you decided to do this pretty long biography, and what surprised you the most about what you found?

RMJ: First, thank you very much for that generous introduction. I respect Richie’s work very much, and he is currently in the middle of researching his own enormous biography of the Velvet Underground, so I hope we’ll be able to talk about points of crossover in our work and the careers of the two artists.

But to answer the question, I set out to be as thorough as possible. I knew that I wanted to look through and read absolutely everything that was available, and to speak to everyone. But I didn’t have specific expectations of extraordinary revelations or smoking guns. I knew that Nick’s life was, broadly speaking, accurately represented already, so what I found the most revealing and useful was the consensus that I was able to gather from his friends, his family, his school reports and so on. There wasn’t much departure from that consensus. Most people’s memories of Nick match up uncannily, even if they’d never heard of each other and never met him together. After interviewing them all I didn’t have to work out who to believe and how to navigate different versions of events.

The privilege of being able to speak to his cousins, and musicians, and Chris Blackwell, all sorts of interesting people who don’t usually speak about Nick and haven’t much in the past, is that I was able to put this jigsaw together and get a coherent whole. I think some people were perhaps hoping I’d find evidence that he was a heroin addict, that he was gay, whatever the big stories would be. But I was neither looking for those nor found them. The strength of the consensus is what really gave me confidence in describing his personality and certain aspects of his work. So, in the way that circumstantial evidence can be more compelling [than a smoking gun] in a criminal investigation, that consensus, to me, was more powerful than any amazing single revelation would have been.

RU: Although I will say, even though I had read as much as I could about Nick Drake before Richard’s book, there were quite a few unearthings of significant information that I was not aware of – and not just bits of trivia. For instance, his musical influences. The book illuminates notable under-appreciated influences on his work, not all of them musical. Maybe unfairly, he is thought of as a ‘folk’ or ‘folk-rock’ musician, but I’ll read out some of the influences from when he was starting his professional career: Astrud Gilberto, Jimmy Smith, Segovia, Odetta, John Hammond, Bob Dylan, Booker T & the MGs, Miles Davis, John Coltrane… And he was able to see in person some of the great British blues-rock bands of the 1960s: John Mayall’s Blues Breakers, the Graham Bond Organization, Cream…

Do you think this wide range, the eclecticism of his influences, has been overlooked and underestimated, and is maybe part of what set him apart from so many other singer-songwriters in the folk-rock bag during that time?

RMJ: I think there’s an element of truth in that. I mean, the word ‘folk’ is unhelpful as relates to Nick. It’s used nowadays simply to mean ‘people with acoustic guitars’, not actual ‘folk music’. Almost the only sort of music that I can pretty confidently say I’ve never heard anyone suggesting Nick ever liked or listened to was folk! I mean, proper English trad folk, or indeed traditional American folk (not blues, but Appalachian or whatever).

But, as you rightly say, Nick did have a broad taste in music, which reflected his generation’s exploratory interest in contemporary culture and what was coming over from America and so on. And at boarding school, of course, boys would bring back records and share them and obsess over them. So there was an informal lending library going on, which was helpful to him. And Nick loved pop, he loved rock’n’roll, he loved West Coast rock – the Doors, the Byrds, Love. And why wouldn’t he? He was excellent, and he loved excellent music.

But I think what’s fundamentally important to remember about Nick’s own musical taste is that he came from a classical place as a child, and classical music was very much his companion in his illness – more, I infer (I don’t know for sure) than pop or rock. I mean, we all know that he was listening to classical music shortly before he took his own life that night. And I think classical music informed his sensibility easily as much as pop or rock or folk and so on.

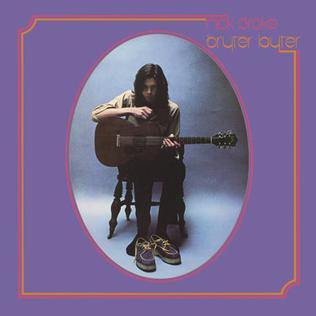

RU: One influence that I always thought was underestimated on him is Donovan. I’m a big fan of his, but until relatively recently he has often been put down by ‘serious’ rock critics. But I’ve always heard – and it’s a compliment – his influence in Nick Drake. And you documented some specific instances: he had a poster of Donovan on his wall, a friend remembered him learning songs off Donovan’s two best albums, Sunshine Superman and Mellow Yellow, and Joe Boyd – the main producer of Nick Drake, who was interviewed extensively by Richard – enjoyed both those albums when working on what I would consider Nick’s best record, Bryter Layter. Do you agree that Donovan’s an underestimated influence?

RMJ: Yes. I think Donovan was a huge influence on other British songwriters in that era, maybe second only to the Beatles among British artists – more so than the Stones, I would say. But I think his influence is often overlooked, partly because he perhaps hasn’t helped himself with the way he has spoken about that era in recent years. But he’s a very fine guitarist, it goes without saying, and probably put just as much work into his style as Nick did. Donovan’s lyrics depart from Nick’s in obvious ways, but I think they’re similar in terms of the structure of their songs and their approach to the guitar. To me, it’s obvious that Nick was listening closely to Donovan’s fingerpicking, especially on the acoustic second record in A Gift From A Flower To A Garden. So it doesn’t seem at all a stretch to me to call Donovan a vital influence on Nick, from 1965 (when Donovan started releasing records) onwards. I think Nick was listening to him right away.

RU: Going back to Nick Drake’s early years, which you document extensively, I think a key point is that not just his parents but other people, like teachers, were almost trying to herd him onto a specific track: going to Cambridge, probably training to be a professional of some sorts. And you wrote that the one thing that nobody seemed to be taking into account in trying to get this mediocre student into an elite school, was: ‘What does Nick want to do?’ Do you think that fuelled his desire to make his own statement, his own career, outside of what was expected of him?

RMJ: I’m sure that dynamic existed. I also think it’s easy to look on Nick’s non-musical life with hindsight and say, ‘Well, people didn’t understand him, people didn’t realise this or should have done that’. But I think Nick was probably quite a maddening person to be involved with as a young… well, he was always young, sadly, but as a teenager, because he obviously had talents, he obviously had abilities, he was charismatic and younger people respected him at school, this was recognised, he was a good leader and so on. He had qualities that were obviously likely to make him into a useful and helpful member of society as an adult. But he was passive – and there was no suggestion that Nick was mentally unwell as a teenager, that there was something larger militating against his future success.

As a result, I think his parents thought, ‘We need to get him into Cambridge by hook or by crook, because his school has said this is a possible outcome for him. So let’s just keep going, because if we don’t he might end up just being at home without much idea of what to do with his future next summer’, or whatever the timeframe was when they started worrying about this.

To an extent – maybe tacitly – Nick’s parents have been criticised for not having recognised that they had a genius in their midst, but that’s not how life works. I don’t think any parent would say, ‘Our teenage son seems to like playing the guitar quite a lot, so let’s assume that he’s going to create a wonderful career for himself doing that’. I mean, it’s just not realistic. But I’ve never inferred the opposite extreme – that Nick’s parents wanted him to be a ‘career man’ and have letters after his name in a patrician, pompous, Empire-building way – and I don’t think that view is supported by any evidence, easy though it is to assume because of his social background and because there was a degree of tension between him and his parents about his not particularly wanting to go to Cambridge in the first place, and then wanting to leave it quite quickly.

I think his parents were actually rather liberal and permissive, within parameters that were normal for that time, and they did allow Nick a lot more freedom than he might have expected or than some of his friends might have had. As I describe in the book, when he went to Cambridge – slightly against his will, but not kicking and screaming – his father worked out a careful and loving, really, arrangement on paper concerning Nick’s finances, and how he would fund Nick in order to allow him to proceed with his music during the university vacations without having to get jobs or think about income. Because the Drakes, contrary to popular belief, weren’t made of money.

So Nick’s parents were supportive of his musical aspirations while he was at Cambridge. There’s a sweet letter from October 1967 where his father says, ‘We opened a bottle of wine to celebrate’ when they heard some good news about one of his early demo tapes making a mark, and so on. But I think it’s unrealistic for us to assume that they should have recognised that he was a great talent earlier than they did.

RU: Before his musical career, in the school reports, the image of Nick is of someone very reticent and almost passive, so it was surprising to me in the book to learn that he had a fierce streak of ambition. He made demos and was shopping them around in London before he had a recording contract, and he was making contacts in music publishing and the record business. And when he was making records, his producer, Joe Boyd, and sound engineer, John Wood, have remembered how forceful he was and how he wanted the records to be made exactly as he wished, he wanted his songs to be represented just as he envisaged them. Is that something you wanted to bring out?

RMJ: Yes. I think this sense that Nick was always passive, that he didn’t make anything happen, everything happened to him, is not supported by evidence, especially from the summer of 1967. I think that was a particularly important year in Nick’s life because he had ten months to fill between getting into Cambridge and actually going there, so he went to University in France in February, he travelled around Morocco, he came back to England in May, then he went back to Paris for a few weeks on his own, and then he was in London for August and September. And over those few months, starting probably around February, he became a songwriter.

And I think in that time a lot of things made sense to him in a way they hadn’t previously. One of the few utterances that we actually have from Nick about his songwriting is that it was only when he went to France that he had the time and space to think about his own personal reaction to the world around him, and how he wanted to frame it. And that’s when he became a songwriter. So I think by the time he got back from France, and before he went to Cambridge, he was committed to a future in songwriting.

And he hustled! He knew that that the way forward was to find a publisher, sell the songs, find a record company, find a producer, and perform. Performing didn’t come naturally to him, or at least wasn’t something that he enthusiastically aspired to, but he understood the need for it – and did it. The first thing he did when he got back to London that summer was to make a recording and shop it. And, lo and behold, almost immediately a major pop song publisher called Hansa wanted to buy some of his songs. They didn’t want to record him, they wanted to buy the songs and sell them to others – which Nick had the confidence, arrogance, whatever you want to call it, to reject.

But I think he knew that he was good, and that he had to fight to be heard. There are some tantalising glimpses that I wasn’t able to pin down. There’s a rather mysterious figure called Calvin Mark Lee, a Chinese-American research chemist based in London. He was one of the signatories to the famous Times advert against the criminalisation of pot, which the Beatles funded, and he was working on the fringes of the record business. David Bowie was his great discovery, and the person whose name his is connected with for posterity, rather than Nick’s, but somehow he connected with Nick in 1967 and was supporting and encouraging him too. [I did speak to him, but sadly he was suffering from dementia and couldn’t remember Nick.]

What I mean is, Nick was out there making contacts, hoping to find a foothold in the music business rather than just waiting around like the entitled upper-class cliché that some sources have suggested he was, thinking, ‘Well, everyone will just recognise my brilliance…’ That wasn’t how he was.

RU: Before we get into the core of Nick’s career – his albums, the songs that he’s so well known for – what are the most important qualities to you in this biography, and in rock biographies in general? What were you trying to bring to this biography that’s lacking in so many popular music biographies?

RMJ: I’m really interested to discuss this, so thank you for raising it. I think that for too long readers have been tolerant of shoddy research in popular music biographies. I think that’s partially because they want to believe in mythology about rock stars. They want to believe that Keith Moon drove a car into a swimming pool, even though that didn’t happen. They don’t necessarily want to read a book about Keith Moon that says, ‘This is just not true’.

But for me certain popular musicians, Nick being one, deserve sober, sensible treatment, because I think posterity deserves eyewitness accounts that are reliable and properly verified. So I wanted to apply the same standards of research and clarity to his life that I would if I were writing a book about Charles Darwin. I’m not comparing their lives, but I don’t think anyone reading a biography of Darwin would be tolerant of half-baked mistruths, blatantly wrong dates and so on. It’s just not the way that biography should work. But I often read pop books and think, ‘That’s just back-to-front, that record wasn’t out then, and this isn’t possible…’

I think that writers like you and Mark Lewison have already shown that it’s possible to approach rock and pop music with a scholarly, but not dry, eye. There’s plenty of amusing facts and details that can be brought into play without having to repeat myths and glorify bad behaviour and so on. So I wanted this book to stand as a serious biography, irrespective of the fact that it was about a ‘pop’ musician.

I also feel that my book almost turns into something else, because Nick stopped making music in 1971, meaning that the last three full years of his life were not spent doing the thing that has fundamentally made people interested in his life. Instead, it pivots into a story about mental health and a family, a dynamic in a family, which doesn’t lend itself to mythologising and to funny anecdotes, for obvious reasons. So from a writer’s perspective I was quite lucky to have two separate stories to tell, really. And the second was obviously a much more sober and upsetting story to balance and to get right.

RU: And I should add that, to try and get that difficult part of the story right, the Nick Drake Estate made Nick’s father’s diaries available.

RMJ: Absolutely. Nick’s father wrote the diary about Nick. It wasn’t a diary that he was writing of old – he started it in March 1972 because he recognised that Nick’s illness was severe and that it was, as he put it in one of his entries, ‘going to be a long job’ (which I used as one of the chapter titles). He realised that the movement of Nick’s illness needed to be watched, so that he and Molly could start recognising ‘the last time he did this, such and such happened…’, or to record when he was or wasn’t taking his pills, and what the effect on his behaviour was and so on. So the diary is really about Nick.

And it’s a brutal document, it’s got little levity in it – but it did give me the huge benefit of knowing where Nick was most of the time, because he was at home most of the time. So I was able to anchor those last years in detail. I knew exactly what Nick was doing for much of the time – what he was watching on TV, what he was eating. The challenge, really, was not making that tedious to read, because of course there are fans of Nick – of whom I’m one – who do find tiny details interesting and revealing, but you can cross a line into pointlessly repeating information that doesn’t have any wider value. So cherry-picking the most salient bits of the diary was one of the most difficult tasks for me, because it would have been easy just to turn the whole thing into prose.

RU: Going to the core of Nick’s musical achievements, his most important musical associate was the producer Joe Boyd. One of the many things I learned in the book that I was not fully aware of was that, besides producing Nick Drake’s first two albums, he thought Nick’s songs could be covered by other prominent artists, some of whom I didn’t suspect. He sent Nick Drake’s songs to Roberta Flack for consideration, although she didn’t record any, but Millie Small, the pioneering ska / reggae singer most known for My Boy Lollipop, did record one of his songs. And Joe also thought that Nick could have written for films. Do you think he overestimated Nick’s potential, or was he just ahead of his time in seeing it?

RMJ: The latter. I do think that Nick’s songs are difficult to cover, but perfectly possible to do justice to. I think Joe felt an immediate sense of discovery when he first heard Nick [in January 1968]. He was convinced straight away that this was a rare talent, and has openly said that he doesn’t understand why others didn’t feel the same way. I wouldn’t say it’s as crude as him having seen dollar signs, I think he just thought, ‘This guy is obviously going to be hugely successful, and I’m lucky enough to have had the opportunity to be his discoverer, to sign him and to work with him’.

So one of the things that Joe immediately anticipated was that other people would form an orderly queue in order to sing his songs, in the way that was happening with Dylan and Donovan and Leonard Cohen and… you name it. Nick’s songs sounded like standards to Joe. So he was paying Nick a publishing advance every week because he was convinced that this was going to be where Nick was going to have his best shot at earning a decent amount of money.

And one of the many puzzles about Nick’s recording career is why so few people did record his songs. There were five or so covers during his lifetime – very few, and none that would have brought in any money. So yes, I think Joe was absolutely prescient, as has been borne out. Obviously, it’s a tragedy for him, as he says, that the success didn’t come when Nick was around to enjoy it.

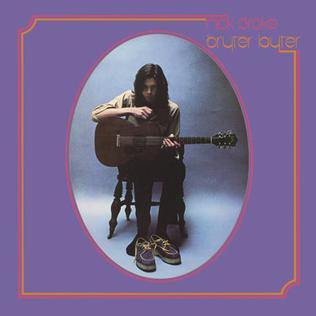

RU: Although Boyd and Drake worked really well together, it was like most producer-artist relationships, they had some disagreements which might have led to better results. One is still controversial among some Nick Drake fans. I like the instrumental pieces on his second album, Bryter Layter, very much, but not everybody does, and Boyd wanted more songs with vocals instead. This is an example of how, although Nick Drake’s image is of somebody who barely said anything and didn’t assert himself, he stood his ground and insisted that the instrumentals were on there. Do you think that’s an interesting part of how they could spur each other on, and work together productively even when they didn’t initially have the same end goal in mind?

RMJ: I think it speaks well for Joe that, although he strongly disagreed with Nick on the subject of the instrumentals, he ultimately did what Nick wanted, not what he wanted. Joe’s memory is that Nick’s vision for Bryter Layter was that both sides should be bookended by instrumentals (although what the fourth one would have been is a mystery – there’s no evidence that one was ever either written or recorded). But I think Joe’s vision was, ‘He’s a songwriter, he sings, he’s not a writer of instrumentals that you could hear on bread commercials’ (or whatever) – and to him, that’s what those instrumentals sounded like. So I think he found it frustrating.

But the most fundamental problem for Joe on that specific subject was that Nick had inadvertently, and slightly uncharacteristically, revealed by playing an encore at a concert in September 1969 that he had another song that was good and that was finished, that Joe otherwise wouldn’t have known of. And that was Things Behind The Sun. And Joe’s ears pricked up, obviously, and he said, ‘Well, obviously that’s going on Bryter Layter, right?’ And Nick said, ‘No, it’s not ready, it’s not finished’. Which was a white lie – Joe had heard it, he knew it was finished. Nick didn’t perform songs that weren’t finished, it’s just not how he operated, he never shared anything that wasn’t finished.

So I think Nick was squirreling away songs for Pink Moon as of 1969. I think he always knew that Pink Moonwas what he wanted to do – not as a reaction to Bryter Layter, as is often assumed, but just as the next step he wanted to take. He knew he wanted to do a guitar-and-voice album as a creative experiment. It was one of the avenues he wanted to explore. And he knew that Things Behind The Sun belonged on that, not on Bryter Layter, with strings and drums and so on. So I think that was a more specific area of conflict for Joe: ‘Why are these instrumentals on here when I know you’ve got another good song?’

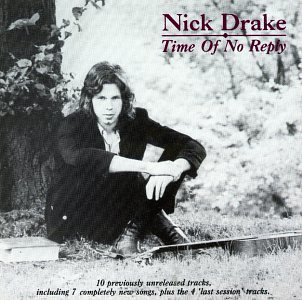

RU: For someone with such a brief career, who only did two known interviews, there are so many rumours and myths around Nick Drake, many of which are unfounded and unfortunately circulate online and in other places. Here’s one that the book clarifies and refutes. It was reported for many years that when Pink Moon, Nick’s third and final album, was done, he went to Island Records and, without telling anybody, just put the tape at the reception and left. Well, the truth might not be as colourful, but it’s the truth and that’s what’s important: he actually delivered it personally to Chris Blackwell, who ran Island Records. What do you think the book does most to set straight about Nick and his career, whether it’s incidents or his character?

RMJ: I think the most important assumption or rumour about Nick that I wanted to clarify is the extent to which he took drugs. It has been said that he smoked dope morning, noon and night, that he was almost addicted to it. The assumption has been that smoking dope defined his days, and probably didn’t help when it came to his descent into mental illness. But most of his friends don’t recall Nick smoking any more of the rest than the rest of them did – which was a fair amount, but socially, and it’s a non-addictive substance.

Now, of course, Nick probably smoked it on his own as well, which didn’t help when he wasn’t in great shape mentally, and I’m not trying to dismiss its possible contribution to his difficulties – but that was an area where I was able to say with confidence: Nick didn’t smoke nearly as much as has been assumed.

In addition, I can find no evidence that he ever took LSD. I mean, it’s perfectly possible, because it was widely around in 1967 and some of the imagery in his songs from that year seem to suggest hallucinatory experiences – but equally, maybe he didn’t. He was a sensible guy, he knew it was a Pandora’s box that not everyone should open. None of his friends remember him taking acid – and they remember taking it themselves, where they were and who they were with. And it was never with Nick.

And then the suggestion that he was a heroin addict, which has often been repeated, including in one or two books, is simply not borne out by anyone’s recollections. So that was something I was glad to be able to set straight.

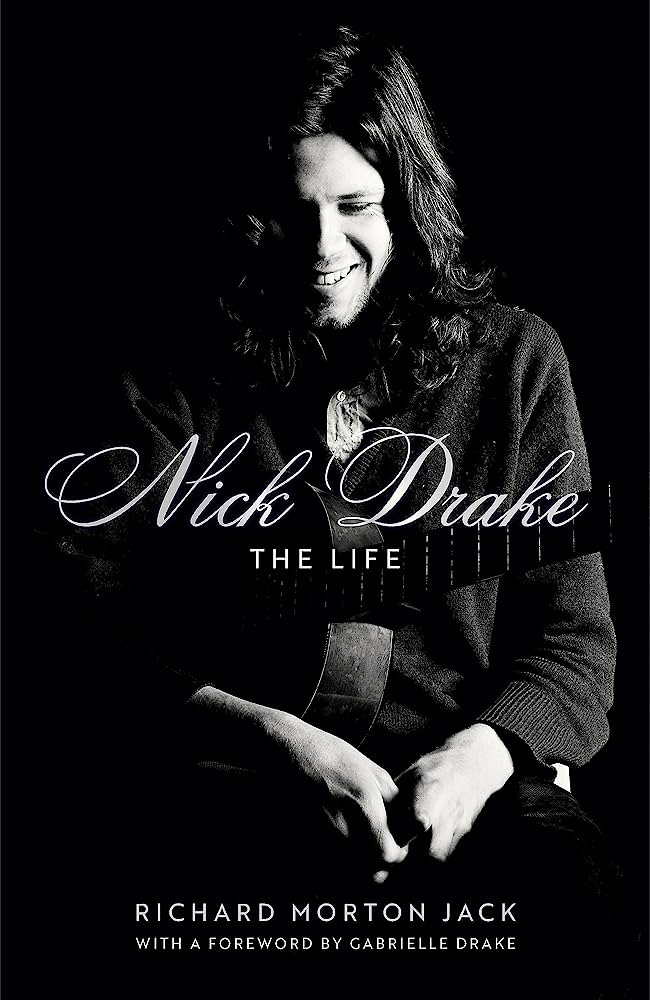

I suppose the other major area that really came through strongly for me, from all people I spoke to, is that until late 1969 – so, shall we say, for the first 21 full years of Nick’s life – he was a happy, outgoing, productive, popular, forward-facing person. So that’s why I wanted, and everyone agreed, to have a picture of him smiling on the front of the book, because that describes how a lot of his friends remember him: first and foremost as an ambitious, cheerful sort of person who wasn’t doomy or gloomy or bad company. Not a flamboyant extrovert, but a good guy to have in a room. So it was gratifying for me to be able to contextualise Nick’s illness with the first, large part of his life and say that really the illness came down like a shutter on him, and doesn’t define how he always was.

RU: There’s a seeming contradiction in Nick’s career. He didn’t do much to publicise himself, although he did play more concerts than is usually reported, about forty. He did a couple of interviews, but rather reluctantly, and didn’t say much. Yet he seemed disturbed that he didn’t have more success and recognition, especially maybe after the second album, which is in some ways a step forward from Five Leaves Left but didn’t get significantly more acclaim. Do you think that lack of recognition helped spark his mental difficulties, or contributed to them?

RMJ: I can’t speak for the psychiatry involved, but approaching his state of mind as if he weren’t ill, I think the sense that he might as well not be bothering was very hurtful. I don’t think he wanted to have gold records on the wall and drive a fast car and have girls screaming at him, but I do think he wanted to feel validated by some sort of audience, a small but loyal audience, and to know that he wasn’t wasting his time, as would anyone who writes or paints or whatever it may be, yet has barely anyone validate them.

In Nick’s case, there are two things to remember. Firstly, he had been led to believe by all of those on the inside of his career, and with all the right motives, that he was going to be very successful. There was no suggestion by anyone that he was marginal, that he should have low expectations of his sales and the take-up of his work. He was therefore quite confident in leaving Cambridge that this was what he needed to do in order to have the success that everyone had led him to expect.

Secondly, to put it crudely, I think Bryter Layter had been his degree. He knew that he couldn’t make Bryter Layter whilst at Cambridge, especially in his third year when he had finals and would have to do a bit of work: he couldn’t just keep coasting and expect to get through his finals. So Bryter Layter was, in a sense, what he did instead of his degree, in the expectation that it would be released in the summer of 1970. The first published, advertised release date for it was that May, which would have dovetailed with when his friends were sitting their finals, and he could have neatly substituted that achievement for his degree.

But there were problems, John Cale was brought in to do a couple of arrangements in June and the release date started being pushed back. Joe Boyd went back to America, there were postal strikes, Island decided to have a major rebranding exercise which held up a lot of releases, then they decided on a campaign called ‘El Pea’ (which involved circulating giant inflatable peas to record shops), and Bryter Layter was postponed and postponed.

None of this had anything to do with Nick, but his record was clearly not a priority for Island. A Cat Stevens or a King Crimson album would have come out straight away, but I think Nick slowly began to realise that he simply wasn’t a priority for Island. That’s not even much of a criticism of Island, it’s just the reality. Five Leaves Left had barely caused a ripple, so Bryter Layter got put on the back-burner.

And that was upsetting for him, because he had left Cambridge in the teeth of fairly strenuous advice from his parents and others whom he respected in order to do something which then wasn’t happening. And then when it did happen, it was released to indifference. So I think those two factors combined to accelerate his low self-esteem and questioning of what he was doing with his life.

RU: This is hindsight, but – especially because I’m from the United States – it seems like barely anything was done to get him an international audience, especially in North America, which might have helped with his desire for some sort of validation, some sort of recognition. When they did put out a record, Capitol Records clumsily combined material from the first two albums instead of, say, putting out Bryter Layter and then, if it had sold well, putting out Five Leaves Left. Do you think that, had Nick gotten more recognition, even if he had been unable to tour in the States, that might have helped with his career and his general perception of the worth of what he was doing?

RMJ: I’m sure it would have – but I think you’ve identified the problem with that in your question, because in those days you didn’t get recognition without touring. It was too much of a shuffle, there was too much competition, and it was so easy to get lost. And, of course, America is a vast territory. You have to be out there visiting the local radio stations, playing second on the bill to Black Oak Arkansas or whoever. That’s what you did. You see these bizarre bills from those days, with obscure English acts supporting American rock acts, because you had to be out there doing that, getting the catcalls. John Martyn did it relentlessly, and he never ‘broke’ America – but he did build up a certain following there.

But by the summer of 1971, when that compilation album came out, Nick wasn’t in a position to perform, or even to travel, really. But I do think Bryter Layter could have done well in America. There’s enough material on it with a sunny, radio-friendly quality for it plausibly to have broken through and made an impact. But again, he just wasn’t a priority for Capitol. They just had too much else going on, and who’s this English guy who no one can get on the phone? It was just hopeless, unfortunately.

RU: You mentioned John Cale playing on Bryter Layter. Especially because I’m writing a book on the Velvet Underground, it’s an interesting connection to me – when the 1970s start you have these areas of rock which seem separate, but there were these unusual collaborations. At the same time Bryter Layter was being made, Joe Boyd and John Wood were working on Nico’s Desertshore, where John Cale was the arranger. Do you think it’s a reflection of the open-mindedness of that time that producers and artists were willing to bring in ingredients that might not have seemed sensible or logical on paper?

RMJ: Yes, absolutely. I don’t think anyone ever anticipated John Cale being a good fit for Nick, it was just an inspired coincidence that he heard some of Nick’s recordings without adornments and thought, ‘I want to adorn them!’, and therefore did. Joe recalls him hopping into a cab that very day, and just going and hammering on Nick’s door.

Joe has open ears and a broad-minded approach to music. Over the course of 1970, the year that Bryter Layter was recorded, he completed, I think, sixteen albums – an awful lot. And the span of those albums is quite remarkable. There’s folk music (what we call ‘folk’, anyway) – Vashti Bunyan, the Incredible String band. There’s jazz, including some quite avant-garde jazz, there’s rock, there’s Nico, who’s maybe called ‘art-song’ now, but I don’t know how she was categorised at the time, if at all… And I don’t think anyone thought that mixture was strange. I think the mixture was what it was all about.

Bringing together musicians from different traditions and backgrounds in order to see what happened was a joyous part of what was going on at the time, and was taken for granted. I think it’s only in hindsight that we think how remarkable it was to have had avant-garde jazz musicians combining with pop musicians and so on and so forth. These endless collaborations, sessions that were full of seemingly unlikely or disparate people making coherent music together, were taken as read then, I think, and Joe was all about the collaborations, that was the essence of Witchseason. He understood that putting musicians together could create magical results, and John Wood regards that as one of Joe’s greatest strengths as a producer: knowing who to bring onto which session to create the best result.

RU: To bring in another Velvet Underground connection, another surprise to me was that a record Nick listened to toward the end of his life, when he was staying with his parents and having a lot of problems, was by Nico. It’s not specified which, but I’m guessing it was Desertshore.

RMJ: Yes – that was in December 1973, and it’s wonderful that Rodney even mentioned Nico by name. There are several frustrating bits in his diary when, completely understandably, he writes things like, ‘Nick came back from Birmingham with three new records today’. And I’m thinking, ‘What were they?’ There’s an entry from July 1974 that says something like, ‘Nick went to a rock concert in London this evening but left early and came home’. What was the concert? It would be fascinating to know. Was it Roxy Music? Who was it? So yes, it’s great that Rodney did mention Nico, because normally he didn’t name names.

RU: I’m a Nico fan, but it seems to me that if you’re having struggles with depression, Desertshore or The Marble Index are maybe not what you want to hear to lift yourself out of that. So that was a big surprise to me.

RMJ: I imagine that he was interested in it because Joe had done it. There’s another bit in Nick’s father’s diary, from September 1974, where he writes ‘Nick went out and bought Melody Maker’. And these things were worth recording for Rodney, because Nick didn’t always have the energy or confidence to face the world, even in terms of a small transaction like that. I got them out and had a look at which issue it would have been – and it had Nico and John Cale on the cover [with Brian Eno and Kevin Ayers]. So I suspect Nick did keep abreast of the other artists Joe was working with, and of course had it in mind that he wanted to work with Joe again himself. So there was a certain logic to his listening to Nico, I think.

RU: Some musicians of great quality – the Beatles or the Beach Boys – reach an audience immediately. Unfortunately for Nick Drake and the Velvet Underground, it took decades. Do you see that as part of the great frustration that Nick experienced?

RMJ: Yes, absolutely. I can only imagine how frustrating it must be to see obviously inferior artists, as you might perceive them, doing a great deal better than you are, attracting that attention. It seems bizarre to me that Five Leaves Left made so little impact. I can’t explain it, no one can. I can understand it not being a number one, or a number ten or a number twenty. But why wasn’t it number 30? I think it could and should have done a lot better than it did. No one has come up with a plausible explanation for that. So Nick must have felt deeply frustrated, especially – as I said earlier – because he had been led to believe that it was going to create ripples.

But, of course, the story of art is of cream rising – Van Gogh and so on. There are so many examples to illustrate the fact that it takes time for it all to settle, and for some of the things that do the best in their day to be forgotten and the artists no one gave any thought to to rise. It’s interesting looking at the charts and reading through the newspapers in those days – there are just so many popular artists from that era that I doubt anyone listens to now. For example, famously – well, famously within Nick Drake’s biographical circles! – one of the only reviews of Five Leaves Left compared it unfavourably to Peter Sarstedt. Now, with all respect to Peter Sarstedt, Where Do You Go To (My Lovely) might be on the radio every now and then, but who sits down and listens to As If It Were A Movie, or another of his albums? They’re not rubbish – far from it – but because he’d had a hit they were widely reviewed. And, inevitably, Nick was compared to whoever was successful in a broadly comparable field, and I think that must have been irritating.

But this process happens, of course, and we end up with the things that resonate the most and that people identify with the most strongly. And I feel there’s an irony about my book, which is that there’s now more knowledge about Nick available than there is about absolute megastars, Jimmy Page or Mick Jagger, say, whose private worlds remain a mystery because they keep them that way, meaning their public face and books are drawn from pretty superficial interviews and so on. But, partly because I’ve got Rodney’s diary, partly because of the amount of people I’ve been able to speak to and so on, I feel that Nick is more known now than they are: his personality and the detail, what he liked doing, what he watched on TV. Because of the access I’ve had and the material his sister has already shared, there’s an awful lot of forensic information that you normally wouldn’t come close to with a major artist.

RU: The first time I spoke to Joe Boyd he was specifically talking about Bryter Layter, and he said, ‘That’s one of the very few records I’ve made where I would not change a thing’. And Joe Boyd has made many records, many really good records. Even at the time, it was inexplicable to him that this achievement was not recognised as such. It wasn’t as bad for him, because he got so much recognition with Fairport Convention, the Incredible String Band, later REM, there are many examples. But to be the originator of Bryter Layter and not get that feedback immediately must have been tough. I mean, even the Velvet Underground got a lot more positive response when they were active than has generally been acknowledged. A lot more, I think it’s fair to say, than Nick Drake did. So in some ways it was easier for them than for him.

My last question, which is another hindsight question, is: had Nick experienced enough success, even if it was on a cult level or making number thirty, as you say, do you think that might have offset his growing psychological difficulties enough for him to produce more music?

RMJ: It’s a lovely thought, but the answer is ‘no’, as far as I’m aware. Not only did Nick’s illness rob him of certain aspects of his sanity, it also robbed him of his creativity. Bit by bit, his ability to generate material, which he had done prolifically for about three or four years, dwindled until he was simply not able to play the guitar and sing simultaneously, or write lyrics. The story of his illness in 1972, 1973 and 1974 is also the story of him desperately trying, in lots of different ways, to recapture his creativity.

And I don’t see his illness as being related to anything else, really. I just think it was sheer bad luck. It’s not because he went to boarding school, it’s not because he smoked too much dope, it’s not because his records didn’t sell. It just came upon him. It happens to people. It’s a terrible tragedy, and I think it’s nice to think of ways in which Nick’s life could have turned out differently. But I fear his outcome was inevitable, based on his illness: it was eating away at him to the point where he couldn’t see any plausible future. I think it would have gratified him if his records had sold better, but I don’t think it would have helped him be creative in his illness.

RU: If anyone else wants to ask anything, please do.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 1: To understand Nick’s mind – thinking of when he first went to France, and then the book that was on his bedside table that fateful night – did you have to read a lot of Albert Camus? And secondly, his family’s house, Far Leys, is at some sort of end of a corner of a shady lane. Is it fair to assume, because Nick was there for three years after the last album, he went walking there, and if I walked there, I’d be sort of walking in his spirit?

RMJ: Firstly, I didn’t immerse myself in Camus. That’s the kind of thing I tried to avoid in writing the book – trying to think myself into Nick’s head and read all the books and Romantic poems and reverse-engineer theories about where his songs came from. I interpreted my role as his biographer quite literally, and that was just to describe his life and try to contextualise his work with it, rather than write pages and pages speculating about which Romantic poets might have informed which lines in which songs. I think that’s a separate and perfectly valid exercise, but for someone to do from a different perspective.

By the way, Le Mythe de Sisyphe wasn’t on his bedside table, so that’s a myth. He bought it in Paris as a birthday present to his mother in November 1974 and posted it to her, but sadly it didn’t arrive because of postal strikes. Instead, rather nicely for her, for obvious reasons, it arrived in around February 1975. So it was ultimately a gift from beyond the grave.

As for walking in Tanworth, I don’t think Nick did much exercise at all in his last years, but of course he knew the village back-to-front. He did occasionally walk a neighbour’s dog, though, so that’s something, and I guess they would go down that path. But if you’re going to walk around Tanworth with the idea in mind that you’re following in Nick’s latter-day footsteps, I would probably say ‘maybe’ but not ‘definitely’. He tended to stay indoors or drive to places.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 2: Do you think the cover of Bryter Layter served him well or not?

RMJ: Your guess is as good as mine! Nick poured so much interest and energy and passion into the creation of his records, not only in writing the songs but also, as Richie was saying, being assertive in the studio – not in a dogmatic, unpleasant way, but he dug his heels in, he knew what he wanted and he got what he wanted – that I find it perplexing that he was so casual about their artwork. He just wasn’t involved in how his albums looked. He didn’t seem to have strong views either way.

Bryter Layter’s cover was photographed by Nigel Waymouth, a friend of Joe Boyd’s. The guitar Nick’s holding belonged to Nigel, the shoes that are in front of Nick belonged to Nigel, as did the chair he’s sitting in. Nick just turned up, then one of the pictures was chosen (by Nigel, not by him), then the artwork was generated. There was a meeting at which it was presented and one of the Island execs present told me that he remembers Nick neither expressing pleasure or displeasure, just not saying anything – and that was that.

But Nick did materialise by Nigel’s side in a crowded room the following year and said, ‘I just want to say that I now understand what you were trying to do with that album cover, and I really like it’. Nigel had no idea what he was on about, but clearly Nick had reverse-engineered some sort of meaning to it and was grateful for it. Nigel remembers the encounter because it was baffling.

I think the picture on the back cover, of Nick watching a car zooming past him on the Westway, speaks more of him in a symbolic sense than a picture of him holding a guitar does. But for me personally, Bryter Layter is so closely tied up with the image of him on the front that I find it impossible to unpick that and imagine it with a different cover.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 3: My father-in-law was at school with Nick at Marlborough and doesn’t remember a single thing about him. He’s even got a photo of them, but he doesn’t remember him. It’s very irritating! Did you find it funny – which is the wrong word – that towards the end of his life he seemed to be on a bit of an up? Also, I found the diary stuff amazing, just so revealing about his character. Looking through the diary, was there anything which surprised you?

RMJ: Are you basing your feeling that Nick was on the up towards end of his life on what I wrote?

AUDIENCE MEMBER 3: The hanging out in Paris, yeah.

RMJ: Nick was very depressed at the end of his life. I think there were glimmers, but what Nick tended to do throughout his illness was make a resolution and then not see it through. And often his parents thought, ‘Well, maybe now something’s changing, he’s becoming positive again, he’s actually going to see something through…’ And then he would crash back into indecision and inability. And that’s basically what happened in Paris. He came back determined to make a new album and get on with life, but unfortunately it was beyond him. I found it quite sad that his parents – latterly, after his death – repeatedly said (and perhaps came to believe) that towards the end of his life Nick had been happier than they’d ever seen him and so on.

But I fear that was wishful thinking, and that they were allowing themselves to concoct a narrative that wasn’t supported by what had actually happened. There were glimmers of positive action from Nick towards the end, but many more of him being at his worst, really. In his last fortnight and on his last day or two he was absolutely as bad as he ever was.

As for Rodney’s diary, of course, it contains lots of valuable material relating about Nick. I think Richie was the first person who read a draft of the book, about a year ago, more or less as soon as I finished it. It was around double the length of the published version, and eliminating material from it was, I thought, going to be impossible because it was so intertwined. Everything seemed so relevant to me. But the realisation that a lot of it was actually repetitive and that, whilst different anecdotes have slightly different weight, ultimately you only need one of them to give the picture, was liberating.

And his illness was the most challenging bit to whittle down, because I wanted to convey its relentlessness and hopelessness, and I was worried that if I cut out too much of the doom and gloom, quite honestly, I might create a false idea that Nick was better than he was – because he was very, very ill. And in the last quarter or so of the book I wanted, without being depressingly grim myself, to convey a sense that the outcome was, in a sense, inevitable, and that the counter-narrative that has arisen that there could have been a different outcome, that Nick’s overdose was possibly accidental and so on, just wasn’t the case. It’s not borne out by anything that I saw.

But the hardest task in writing the book was trying to streamline the last part, because there is just a lot of relentless material in Nick’s father’s diary. It’s not an easy read and I don’t think much would be gained from it being published in full, really. It’s a heartbreaking document.

That said, if you strip out the awful tragedy at its heart, there’s a lot of mundane information, most of it relating to Nick, but it’s what they were eating and what they were watching on telly, and Mr. Heath has lost the election, all this sort of stuff, so it’s interesting simply as an account of an early 70s household.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 4: A bit of an impossible question. How long does it take between someone dying an unknown, then getting known, and then becoming this incredible figure?

RMJ: I think that’s a really interesting question – and of course, it’s case-by-case. How many are we still waiting to hear of? But speaking about Nick, I think it’s interesting to speculate, as a fantasy: had he been willing to play a concert in September, October 1974 and a promoter had said, ‘Yeah, sure’, what would the take-up have been? I suspect larger than Nick might have anticipated. I think he was better known than he realised, and perhaps better known than posterity has acknowledged.

We all know that he had tracks on Island sampler albums in his lifetime, which sold huge numbers, so there was that. But I also think his albums had cumulatively reached a larger audience than has been acknowledged. You see these made-up figures – ‘a combined total of 5000 sales during his lifetime’ – but no one knows what his records sold in his lifetime. The earliest source I have that gives a number is that, at the time of Nick’s death Bryter Layter had sold 15,000. Now, that’s not a large number, that’s not enough to get you into the charts – but it’s not nothing.

So I do think he had a larger fanbase than he realised – because it’s really good music. People picked up on it and said, ‘You should listen to this’ in student halls and so on, and word had spread. But no one knew who he was, no one knew how to contact him, no one could see him live. There was no visibility. So I think Nick was isolated from his audience to the extent that maybe he didn’t even realise there was an audience.

At time of his death, Nick was trying to get an accounting for the last few years. Island hadn’t accounted him properly, and I don’t blame them particularly for that – there was a degree of chaos between Witchseason and Joe Boyd and Island, and it was all being sorted out. But Nick’s arrangement had been that, after recording costs had been met on his albums, he would get 50% and Witchseason would get 50%. Of course, Pink Moon cost barely anything to record, so that was almost immediately profitable. But what Nick wanted to know at the end of his life was, ‘Am I owed any money? What’s the situation?’

Well, I’ve seen the royalty figures for the years immediately following his death. At the end of 1974, shortly after his death, his royalty statement for 1972-1974 was finally organised. That was about £1800, which is about £16,000 now. The figure for 1975 was lower, because it was only for 1975. But for 1976, 1977, 1978, 1979, the figure got bigger each year. So there was a growing interest straight away – and this was before he was being revered as a James Dean-type figure.

So I think, whether or not Nick had died, his records were picking up momentum. But then, of course, the whole cult surrounding his death contributed towards his mythology and status, and that process has never stopped.

RU: I want to add that I think it’s been overemphasised that the use of one of his songs in a commercial was responsible for elevating him out of obscurity, because – as Richard notes – the ‘cult of Nick Drake’, if you want to call it that, was building and building way before that. In some ways it’s similar to the artist I’m working on now, the Velvet Underground. If that Volkswagen commercial had not appeared, I think his following now would be about as big, or only slightly less, than if it had not appeared. It’s the music that’s done it, it’s not because of the fluke that it was selected for a commercial.

And a final thing: Joe Boyd deserves an enormous amount of credit for making sure that Nick’s records were still in print, and that a boxed set was still in print. That made sure that awareness could continue to build (unlike with some artists, like Skip Spence, where you couldn’t get the record for many years). And I think it will continue to build indefinitely, for generations beyond us.

RMJ: I agree with that. The suggestion that the Pink Moon advert is where Nick’s story suddenly changed is, as far as I’m concerned, inaccurate because his records were freely available all over England in the 1990s when I was a teenager. Listening to Neil Young, listening to Bob Dylan, listening to Joni Mitchell, listening to Nick Drake, it was all the same by then, in the UK at least. He wasn’t on the level of someone like Townes Van Zandt, where you might still feel, ‘This is really quite an obscure guy’. I mean, Nick was well-known in the 90s, as far as I was concerned, getting to grips with my own musical tastes.

And the sense that his reputation will continue to build was really the main motor for getting my book done. Gabrielle understood that – although it slightly stuck in her craw to reopen the wound, as it were – interest in Nick is not going away. And therefore the facts need to be straight, because too many misapprehensions have been taken as fact in the absence of a sober inspection of everything that there is in her possession, and in the memories of those who knew him but hadn’t necessarily spoken about him publicly.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 5: I’m interested in Nick Drake’s classical influences, which you alluded to – you mentioned that he listened to classical music in the last years of his life, and I hear the influence of Debussy in some of the string arrangements on Five Leaves Left, for example. What have you been able to find about the kind of classical music he listened to?

RMJ: Frustratingly, Nick’s record collection – although really it was more of an accumulation, as he wasn’t a ‘collector’ in any serious way, and I understand he treated his records quite casually – has been dispersed, partly given away by his parents, or pinched by fans, left lying around and eventually chucked, I don’t know. So there isn’t a sort of block of ‘Nick Drake’s record collection’. There are a few which have been kept, including copies of his own albums and one or two John Martyn albums and the Brandenburg Concertos and so on. So I don’t have a clear answer to what classical recordings he most liked.

But I would say, on a tangent of sorts, that another myth about Nick is that ‘Robert Kirby wrote the arrangements’, that the arrangements were just grafted onto Nick’s songs. I actually think one could almost say it was generous of Nick to give Robert the arrangement credit, because the arrangements were by the two of them. Nick was sitting at the piano or with a guitar, making suggestions, and Robert was sitting over there, writing, and Robert would say: ‘Well, how about this instead of that?’ It was absolutely collaborative all the way through those two albums. Nick knew what he wanted, and the arrangements were written very much with him. Robert was much more than an amanuensis, but it was certainly a collaborative effort.

Robert’s main reference points were classical. but he loved the Beatles and George Martin, and understood the difference between writing classical music and pop arrangements, and that you had to have a pop sensibility. So I think the influences on Nick’s arrangements were towards the more pop end of classical, shall we say? Robert referred to the artists or the composers that he and Nick had in mind – Fauré, Debussy, Delius, Vaughan Williams. And I don’t mean to sound insulting to these composers, I just mean the more overtly melodic parts of their work.

In terms of Nick’s private passions within classical music, I don’t know. But I can say his tastes were catholic and he liked symphonic music, he liked solo piano, he had a broad understanding and enjoyment of the canon.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 6: I just want to challenge you. I’m wondering whether you are yourself mythologising a little bit when you talk about the inevitability of his death because he was so ill. I’m just wondering, have you yourself been through a period of acute mental illness for two years or longer?

RMJ: No, not in the least. It’s absolutely fair to take me to task on that.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 6: It’s more a point about mental illness than Nick Drake himself: who knows whether he would have come out of it or not? If you’re in that state for a long time, what happens is there is atrophy generally. You can’t think, you can’t move, it’s difficult to have ideas, it’s difficult to be creative. You feel like you’ll never come back from it and you’re on the brink – and I’ve been through this, I’ve been on the brink – but often there is a return from that. And when you begin to return from it, things come back.

So I think your narrative, that there is no return, is a kind of mythologising and needs to be challenged. It’s a general point about mental illness. I think it’s dangerous to say, ‘There can be no return’. If Nick Drake was at a point where he could take his own life, I think one would have to say that may have been a situation which could have been turned around, just by chance. Someone could have come back who may have had what he needed at the time, and the next day there would perhaps have been onward movement. So I want to challenge you on that point. That’s all I’m saying.

RMJ: I’m happy for you to have done so, and I apologise if what I was saying seemed glib.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 6: I’m not saying that you’re glib. I just want to make that point.

RMJ: I take it on board, and I’m delighted that your experience has been different to Nick’s. And I don’t say he was never going to get better with any levity. What I think I was – perhaps clumsily – trying to express was the fact that the counter-narrative that he was ‘getting better’ towards the end of his life is not borne out by evidence. I think a lot of Nick’s admirers – with the best of motives and goodwill towards him – want the outcome to have been different, and have therefore seized on small glimpses that have entered the history books, as it were, of him having been happier and much better, and of having taken far fewer pills on his last night on Earth than he did.

And for me, revisiting his last weeks or months and trying to construct an accurate version of how he was, day-by-day and week-by-week, left less room than I think has been widely understood for thinking that he was in a more positive frame of mind at the end of his life and therefore that the outcome might have been more positive. But you’re absolutely right, of course. One should never write off anyone psychologically, and I didn’t mean to.

RU: Thanks, everybody, for coming today. And I hope, again, if you have not bought a copy of the book, you will get a signed copy on your way out.

RMJ: Thank you.