In my Ball Four Outtakes post a few months ago, I discussed the unedited full transcripts of the audio tapes Jim Bouton recorded for the basis of his classic book about his experiences in the 1969 season. These are available at the Library of Congress, though you have to make arrangements to view them in person at the library in Washington, DC. I also detailed some examples of interesting material that didn’t make the book, even if Bouton and his collaborator/editor Leonard Shecter almost always picked the best stories and observations for the final manuscript published in 1970.

There are many other items that didn’t make the book, some trivial or of not nearly as much value as what made the cut. Some of the omissions, however, were noteworthy, even if they weren’t on the level of what you read in Ball Four. Here are a few other examples, for what might be called Ball Four outtakes.

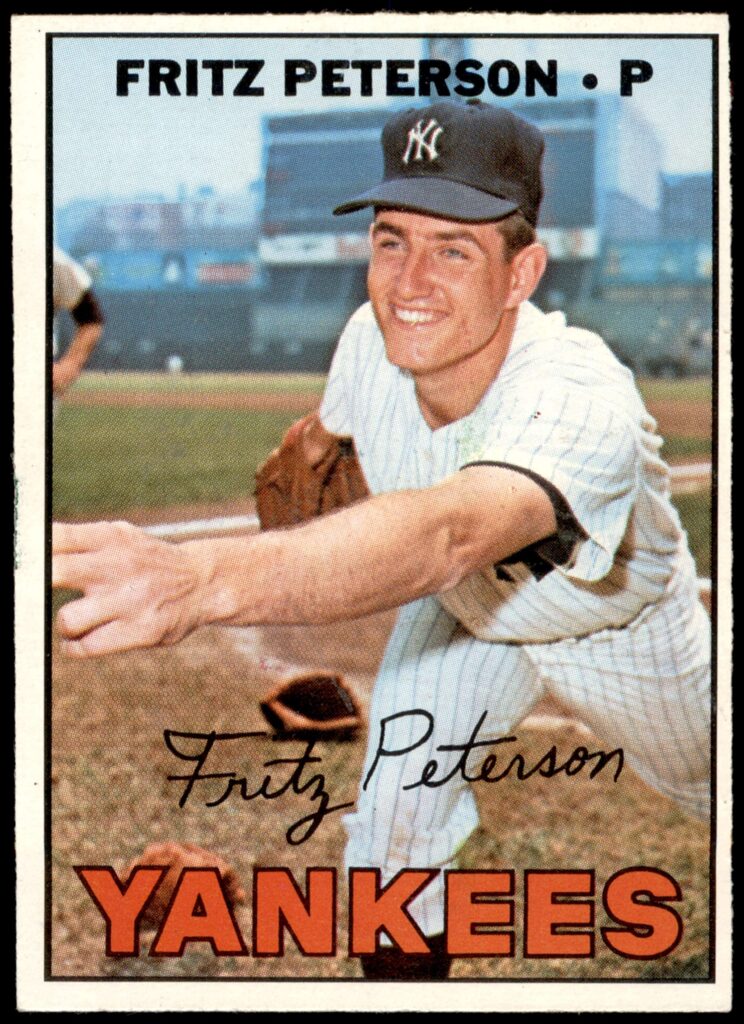

**One of the most colorfully controversial stories of the era in major league baseball took place the year after Ball Four, when Dock Ellis pitched a no-hitter, or so he at least sometimes claimed, on LSD. Acid isn’t mentioned in Ball Four, but it turns out shortly before 1969, Bouton and fellow Yankee pitcher Fritz Peterson went to Haight-Ashbury and were offered LSD by a youngster calling himself the Acid Man. Bouton demurred, in part because he thought he might be used in relief (presumably the Yankees were playing in Oakland). Peterson pointed out Jim couldn’t pitch any worse on LSD, considering how he’d been pitching of late.

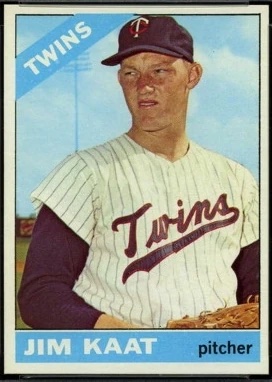

**There’s an interesting observation on pitcher abuse, before that term was used, that’s both perceptive yet at the same time illustrates how faulty memories could be even four years after the fact — and how difficult it was to check on their accuracy in the days long before baseballreference.com. Bouton’s career went sharply downhill starting in 1965, when he went 4-15 with a 4.82 ERA after winning 21 games in 1963 and 18 in 1964 (and pitching very well in three World Series starts, winning two of them in 1964). He blames the sore arm he developed in 1965 in part on pitching eleven innings on a cold-weather opening day versus future Hall of Famer Jim Kaat, whose Minnesota Twins went on to win the pennant that year.

These days no pitcher goes eleven innings, let alone on a cold opening day after, according to Bouton, going no more than six innings in spring training. As he correctly points out, it’s poor management to risk someone’s long-term career by using a pitcher that way in cold conditions so early in the season.

But when you go to baseballreference.com to check the boxscore, it didn’t happen that way. Bouton went just five innings, not pitching that well, giving up four earned runs. The game did go eleven innings, the Yankees ultimately losing. Maybe Bouton felt sore during or after the game, and retrospectively blamed this on pitching too long when remembering how long the contest lasted. Whatever the case, he never would pitch too well in the majors again, though his status as opening day starter indicates the Yankees were expecting him to.

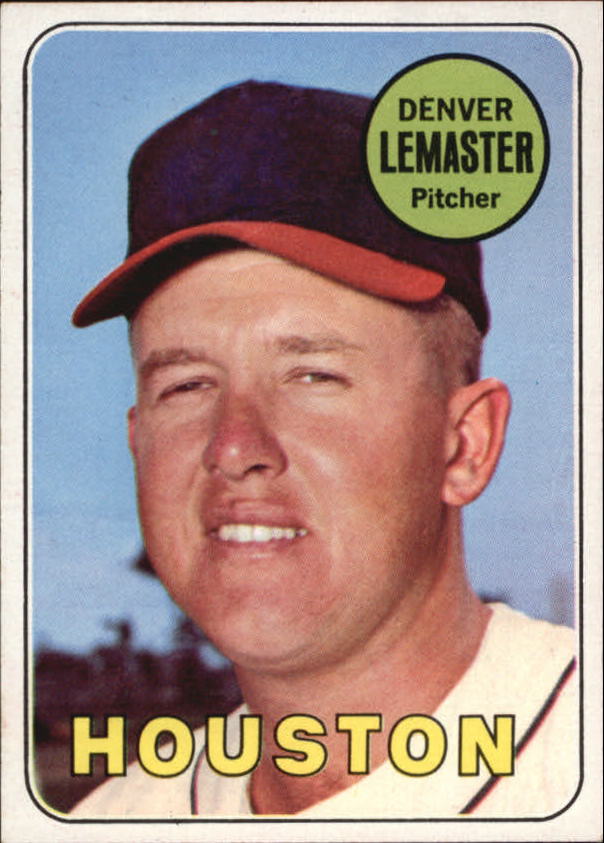

**In about the only story in the book that reflects badly on a member of the Astros, Bouton writes about a fight breaking out on the team bus after Jimmy Ray makes fun of Wade Blasingame. Several members of the Astros got up to block a coach’s view of what was going on, so the incident didn’t blow up any more than they thought necessary. In the transcript (but not the book), those members are named: future Hall of Famer Joe Morgan, star outfielder Jimmy Wynn, and Curt Blefary. Jim especially praises pitcher Denny Lemaster for telling the coach (also named, Buddy Hancken) to get back to the front of the bus where he belonged. Bouton also hails Lemaster, the Astros’ player representative, for not being shy of standing up to coaches and the team’s general manager.

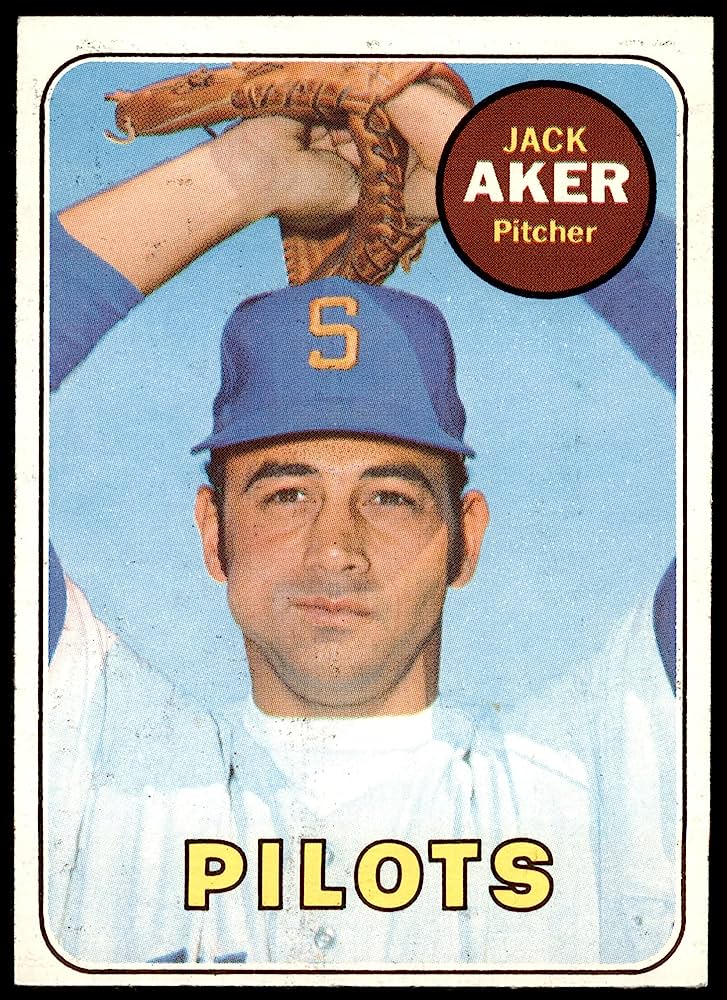

**In a take on baseball politics that didn’t make it into the book, Bouton notes that player representatives seem to get traded more often than others, in the days when a strong baseball union was just getting off the ground under Marvin Miller. This is specifically sparked by relief pitcher Jack Aker, the Pilots’ player rep, getting traded early in 1969. Aker, who generally had a good career (including leading the American League with 32 saves in 1966), was off to a poor start with Seattle, with a 7.56 ERA after fifteen games, which could be seen as reasonable justification. He was traded to the Yankees for Fred Talbot, who had a mediocre career (and barely pitched in the majors after 1969), and to Bouton the trade didn’t make sense. Aker righted himself with the Yankees, putting up a 2.06 ERA the rest of the year, and had five more good-to-average years.

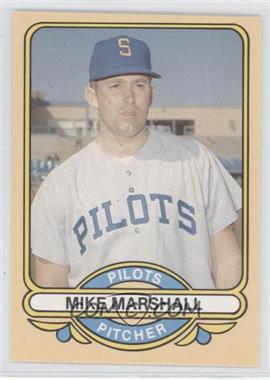

**Mike Marshall would become one of baseball’s most successful relief pitchers for much of the 1970s, albeit with some down years. In 1974, he won 15 games and saved 22, setting a still-standing record for pitchers of appearing in 106 games. In Seattle he was used as a starter and, after some early success, did poorly, getting sent down to the minors in July. Bouton points out that in the minors he quickly pitched better, in part because Marshall was able to set his own pitching program instead of fitting into what Seattle wanted. He also points out that after seeing Jack Aker pitch much better with the Yankees, Pilots manager Joe Schultz might be starting to understand that it was better to leave pitchers alone with their methods instead of trying to impose these on them. Schultz wouldn’t have much of a chance to try that out, getting fired after the season, the only one in which he’d manage in the big leagues.

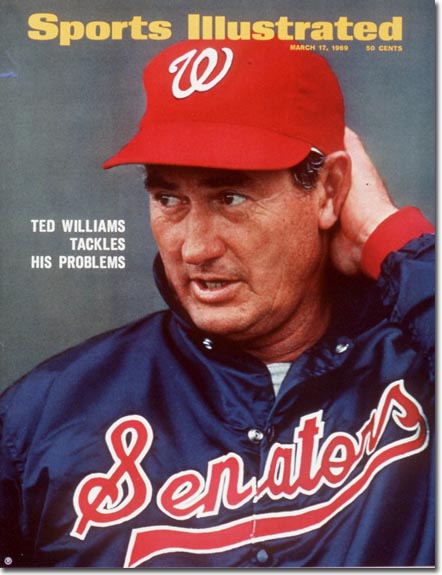

**There aren’t many comments in the book about then-Washington Senators manager Ted Williams and then-Minnesota Twins manager Billy Martin, but the ones that were used weren’t negative. In the transcripts, Bouton does cite a newspaper article — probably hard to track down now, especially as he doesn’t name the publication — where Martin criticizes Williams for being the kind of player who wouldn’t get his uniform dirty or slide to break up a play. Jim admires Martin for having the guts to say this, considering how canonized Williams, one of the greatest hitters of all time, already was by 1969. Acknowledging he never saw Williams play, Bouton does remember Ted being a player who didn’t give his all on defense or being that well-rounded in his effort.

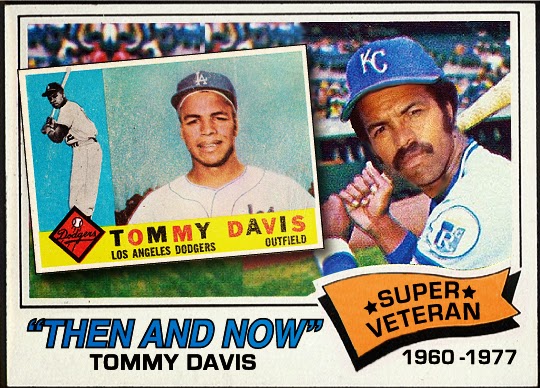

**Bouton’s very complimentary about Tommy Davis in the book. Briefly a superstar in the early 1960s with the Dodgers, when he one two batting championships, Davis never recaptured his peak performance after breaking his ankle in 1965. But Jim praises Tommy for being one of the Pilots’ team leaders. Of greater interest, he notes that on most other clubs, there were factions in which team leaders gathered around black players or white players, without overlap.

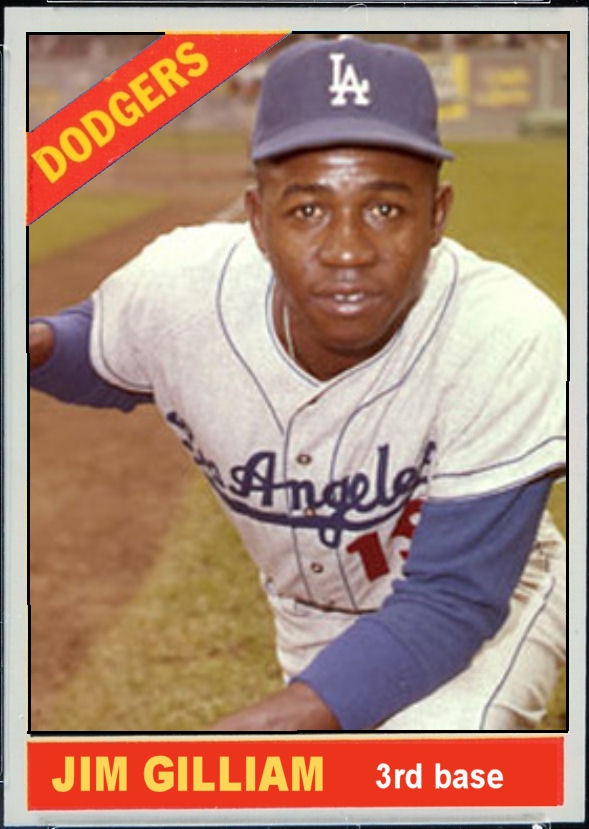

**In a small fun story about how the game is played, Bouton remembers how umpires would speed up games to make sure they finished quickly, whether because of rain or other reasons. Specifically, he relates a story from Tommy Davis of how on the Dodgers, Junior Gilliam was told by an umpire who had an appointment to get to with one out in the ninth inning that if there was a ground ball, Gilliam could get the first out and the umpire would get the second to complete the double play. Gilliam got a ground ball, and the umpire called the runner out at first base before the ball got there.

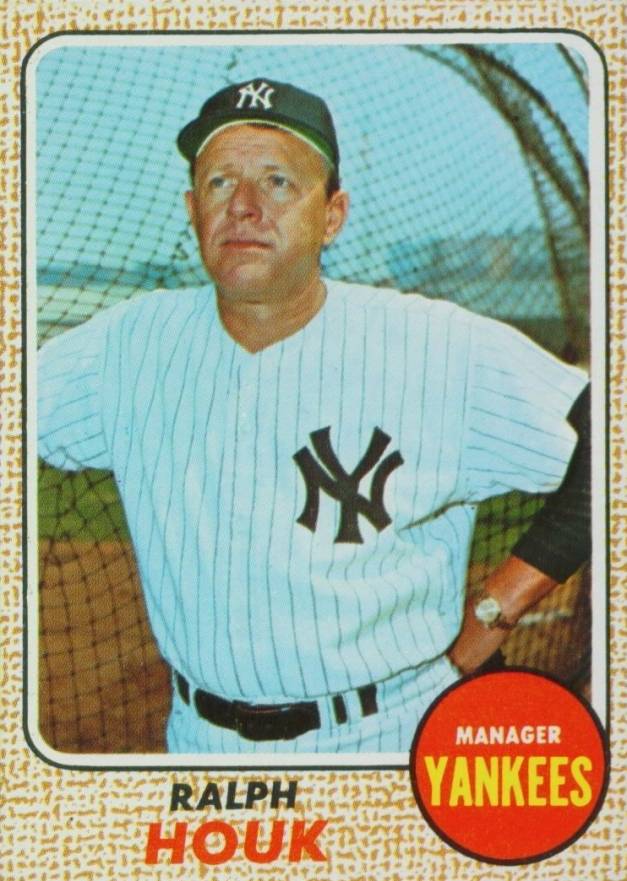

**In Ball Four, Bouton is very critical of some elements of the Yankees, whether specific players, the culture of the club, the executives he dealt with, or manager Ralph Houk. Yet he wanted very much to be able to play for them again, if in large part because his home and family were in New York and he wanted to be based there. Extraordinarily, he even said he’d be willing to go to New York’s minor league system to work on his knuckleball if he could get back in the organization. He noted he’d be willing to play for the Mets too, though 1969 being the Miracle Mets year of their surprise World Series championship, there wouldn’t have been a place for him on that club. Bouton never did play for the Yankees again, and in fact he wasn’t invited back for a Yankees old-timers day until 1998, with the help of a New York Times article from Jim’s son Michael urging the Yankees to lay aside grudges stemming from his father’s remarks in Ball Four.