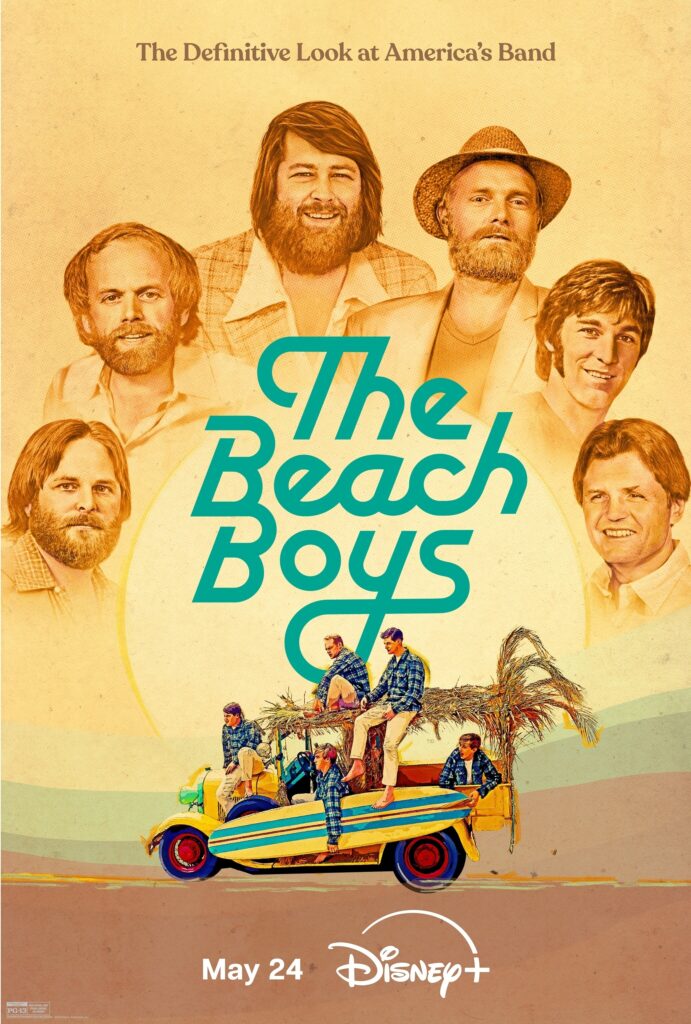

It’s Beach Boys Spring—not the summer, as you might expect—with the appearance of two major projects championing the group’s legacy. The first to get issued was the book The Beach Boys By The Beach Boys, and I wrote about some of the more interesting aspects of that volume in my previous post. The other is the two-hour documentary simply titled The Beach Boys, which is streaming on Disney Plus.

It doesn’t have much in the way of previously unknown facts and stories, if you’re very familiar with the group’s history. Unlike the two previous full-length documentaries on the band, An American Band (1985) and Endless Harmony (1998), it does not gloss over a few of the darker sides of their story, particularly the role of Murry Wilson (father to three of the Beach Boys and uncle to another) in their career and (far less extensively) Dennis Wilson’s friendship with Charles Manson. Besides recent interviews with surviving Beach Boys Mike Love, Al Jardine, and Bruce Johnston, there are also interviews with associates who are less heard from, including David Marks (who was in the group on their first few albums), Brian Wilson’s first wife Marilyn, and Blondie Chaplin, who was in the band for a while in the early 1970s.

Like my post about the book, this one isn’t a review of the film, which I’ll put on my year-end roundup of documentaries. It will focus on the more interesting and less-traveled perspectives heard in the movie.

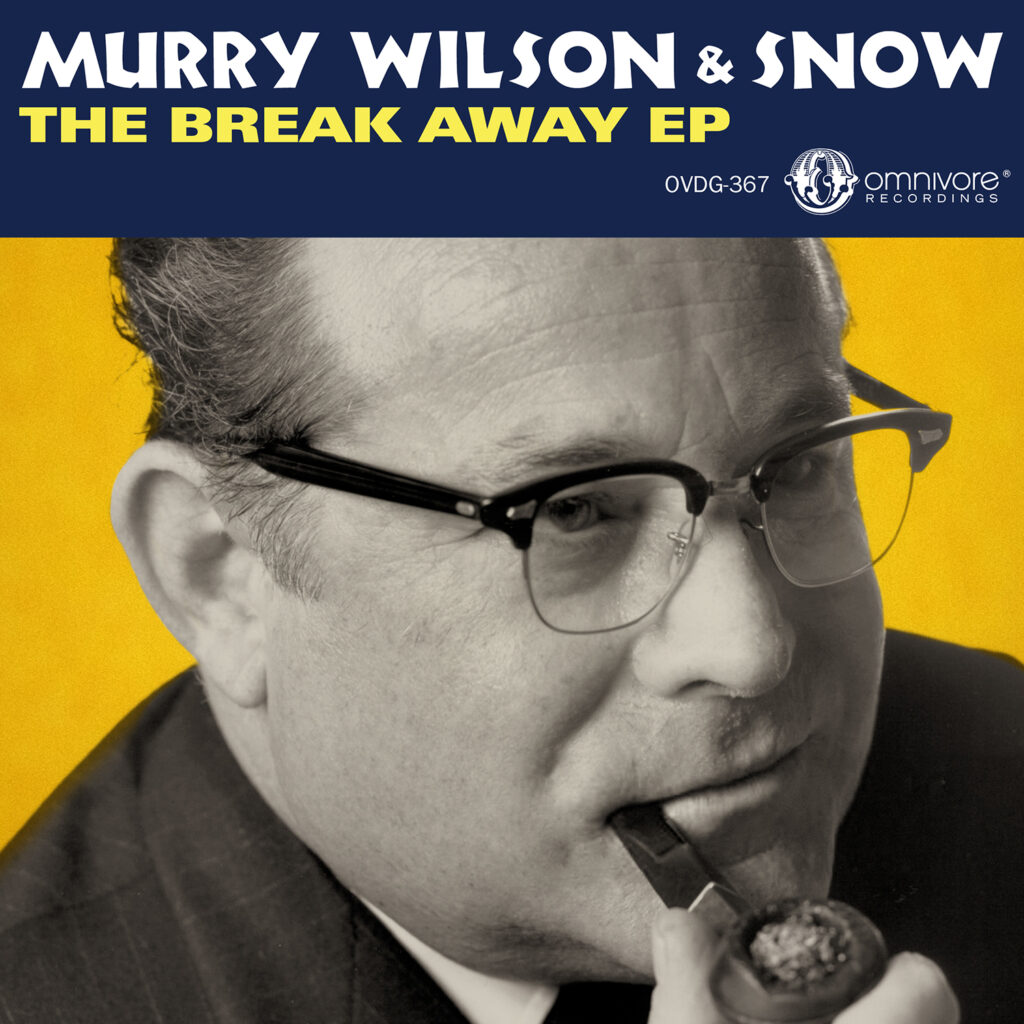

Murry Wilson. A good amount of space is given to Murry Wilson’s work with the group as their early manager and then publisher. More of the coverage is negative than positive, though different sides of the story are given. He could be rough on his kids when they were growing up, and a more accurate description seems to be that he could be abusive. That’s been documented in some books, as well as some bootlegged chatter from recording sessions, and led to him being fired by the group not long after they’d become superstars.

As far as how difficult he was to get along with as the Beach Boys were getting off the ground, Marks remembers Murry even adjusting his guitar amps onstage. It’s also discussed how he’d intrusively signal to the band to adjust their sound during concerts and fine them for minor indiscretions, leading to Marks quitting the Beach Boys in late 1963. They did let him keep handing their publishing, which led to serious problems down the road, Murry selling their publishing for an undervalued $700,000 in 1969.

Mike Love expressed a lot of displeasure in his memoir for, in his view, not getting enough songwriting credits, or the compensation he deserved as a contributing writer to much Beach Boys material. He criticizes Murry’s work on the publishing end in the documentary, remembering that Murry said he’d sell the publishing back to the Beach Boys, but he didn’t, and that Murry didn’t credit his songwriting contributions on a number of compositions. “I got cheated by my uncle,” he says. “He screwed his own sons, and grandchildren.” Brian’s first wife Marilyn (now Marilyn Wilson-Rutherford) has a more personal angle, noting the sale upset Brian so much that he stayed in bed for three days.

So yes, there’s a lot of bad stuff about Murry. But the documentary does air some more positive perspectives about the father. It was Murry, Love recalls, who got them into the studio, where they cut their debut single “Surfin’,” a big local and small national hit that did kick off their recording career, although it wouldn’t truly take off until they signed to Capitol. Other sources have also acknowledged Murry did a great deal for the group in their early days, including hustling them to labels all over Los Angeles and being instrumental in getting them onto Capitol with his persistence. While Marilyn Wilson-Rutherford detailed the publishing sale’s devastating impact on Brian, she’s also the most vocal in acknowledging Murry’s attributes. If he wasn’t there protecting them, she opines, they wouldn’t have become nearly as big. She also goes as far as to declare, “If there was no Murry, there would be no Beach Boys.” Leading viewers to wonder, if only he could have both helped their career without being such a bully to them personally—but too often, both qualities are found in tough businesspeople.

Birth of the Beach Boys: The story has often been told that the Beach Boys became serious, or at least seriously semi-professional, when Murry and Audree Wilson took a vacation to Mexico in late 1961, leaving their sons money for food in their absence. This story goes that the brothers instead used the money to rent instruments and work up material, incensing Murry when he returned, but cooling him out when he heard the results of their rehearsals, sparking him to help set them on the road to recording and stardom. Screenwriters might consider it a good setup for a biopic, but Al Jardine sets the record straight (as has previously been reported elsewhere) in hs interview. It was Jardine’s mother, he says, who gave them $300 to rent equipment. A big sum, by the way, in 1961; that’s equivalent to about $3000 today,

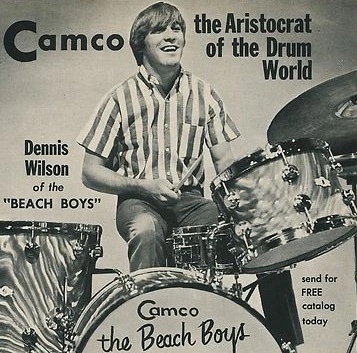

Denny’s Drums: That’s the name of an instrumental on an early Beach Boys album. Dennis Wilson is not the most highly regarded drummer from a famous rock band. It’s often been reported that many of the Beach Boys’ drum parts were recorded by session musicians, especially Hal Blaine. It’s also sometimes been written that he’d rather spend time having fun, at the beach in particular, than in the studio. Even in this documentary, Al Jardine observes Dennis would rather be in the water than in the studio.

Yet Jardine also says in the doc that Dennis, who’d been included in the band at least partly due to his mother’s insistence, learned the drums quite proficiently. And Marilyn Wilson-Rutherford says that Dennis is actually usually on drums on the Beach Boys’ records. Blaine and Jim Gordon certainly played drums on some Beach Boys discs, including some of their most highly esteemed recordings. But it does seem like Dennis was a more significant contributor as an instrumentalist on Beach Boys sessions than many assume, as is true of the Beach Boys as a whole. Certainly he plays very enthusiastically and serviceably well in the live ’60s footage of the group, if hardly with the finesse of the best drummers of the era.

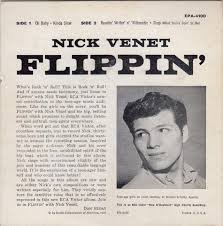

Nick Venet: Nick Venet is credited as the producer of the first two Beach Boys albums, Surfin’ Safari and Surfin’ USA. He isn’t given much credit, in the descriptive rather than official sense of the term, in histories and by the Beach Boys. In the new documentary, Brian Wilson (in an archive interview) says Venet didn’t do much besides announce take numbers.

In a voiceover interview excerpt, Venet ascribes his ousting from production duties as due to Murry, who as noted in their early days took an aggressive role in the group’s direction, which included musical matters. When Nick told Murry he was wrong, Venet remembers, the band took it as a slander against the whole family.

It might be impossible to determine if Venet did much besides acting as a functionary of sorts, but at least a couple of things might be noted in his defense. If his credit on Beach Boys records might have been symbolic, he wasn’t just some bureaucratic attaching his name to productions. His production resume, much of it compiled after his brief time with the Beach Boys, includes a lot of impressive albums, most notably folk-rock singer-songwriter Fred Neil’s self-titled 1966 Capitol album; the Stone Poneys, Linda Ronstadt’s group prior to her solo career; and early Los Angeles folk-rock group the Leaves. Indeed he was one of the more significant 1960s folk-rock producers, also working with John Stewart in his early solo career, and with cult folkie Karen Dalton.

He deserves ultimate credit, too, for signing the Beach Boys after they—according to this documentary and other accounts—were rejected by quite a few labels, whether or not he did much in the studio afterward. An issue that’s not discussed much is why the Beach Boys had trouble landing a deal after their debut single “Surfin'” had significant success. It’s easy to say in hindsight, of course, but it seems obvious from listening to their pre-Capitol recordings that they both had some appreciable if raw talent, and that they sounded appreciably different from other rock bands of the time.

That’s evident not just from “Surfin’,” but also the numerous other recordings they made with Hite and Dorinda Morgan (best heard on the double CD Becoming the Beach Boys: The Complete Hite and Dorinda Morgan Sessions, even if many of the tracks are multiple versions of a small group of songs). These included early versions of two big Capitol hits, “Surfin’ Safari” and “Surfer Girl.” At a guess, maybe the Beach Boys were considered something of a one-shot novelty group, both because of the lyrics of “Surfin'” capitalizing on the surfing craze, and because of the name the Beach Boys, which might have suggested they were manufactured to suit that specific song.

Al Jardine rejoining: The usual perception of the Beach Boys’ timeline has Al Jardine in the group at the very beginning (including on the “Surfin'” single), then leaving to concentrate on college, being replaced by the Wilsons’ young neighbor, David Marks. Then Jardine rejoining when Marks quit/was fired in late 1963. But as the documentary verifies, it’s not that simple. It has Brian Wilson’s discomfort with touring—often reported to have come to a head at the end of 1964, at which point he left the road to concentrate on writing/recording/producing, replaced for a while by Glen Campbell and then long-term by Bruce Johnston—surfacing in 1963.

That, the film notes, is when Al Jardine rejoined, or at least often filled in for Brian, not Marks. With Marks’s departure, Brian then had to go back on the road until late 1964. For a while Jardine and Marks were in the same group, at least onstage. Ian Rusten and Jon Stebbins’s The Beach Boys in Concert book confirms Jardine filled in for Brian as early as a spring 1963 midwest tour, doing so off and on for a while until Marks left and Al settled in for good.

As I also observed in my previous post, although Jardine is the least colorful and least discussed of the five core Beach Boys, his contributions weren’t entirely peripheral. Part of the reason he stayed for good was that he was considered a better singer, and certainly vocal harmonizer, than Marks. It’s noted in the documentary that Jardine had perfect pitch. When I interviewed Dean Torrance of Jan and Dean about eight years ago, he told me, “his vocals were spot-on. Al was great. So they all contributed. It was an ensemble, and everybody had an important piece to contribute.”

Marks’s contribution to the group is generally underreported, and there’s a lot more about him and that stint in his book The Lost Beach Boy, co-written with Jon Stebbins.

The Beach Boys on the Beatles: The Beach Boys’ admiration for the Beatles is well documented, as is the Beatles’ high regard for the Beach Boys, though it’s usually Paul McCartney who vocalized that. Some comments in the documentary, however, indicate the Beach Boys didn’t know quite what to make of the Beatles when they unexpectedly invaded the US with massive success in early 1964. Recalling the time when “I Want to Hold Your Hand” took over the US airwaves, Jardin describes them as a little crude, and players, whereas the Beach Boys were singers. In an archive interview, Brian Wilson states “I Want to Hold Your Hand” “wasn’t that great a record.” It’s not a big deal considering Jardine, Brian, and the other Beach Boys quickly became big Beatles fans, but it’s peculiar.

Mike Love as co-writer: Love co-wrote a lot of ’60s Beach Boys songs with Brian Wilson, including some big hits, his contributions primarily being on the lyrical end. As previously noted, he has said and written that he should be credited on some others. Brian did write with some others in the ’60s who weren’t in the Beach Boys, including Gary Usher, Roger Christian, Tony Asher (for most of the Pet Sounds album), Van Dyke Parks, and even, on the 1969 single “Break Away,” his father Murry (who used the pseudonym Reggie Dunbar). In the documentary, Love says a reason for this was that when the Beach Boys were on tour without Brian, he wasn’t available to collaborate with his cousin.

Yet Wilson was writing with Usher very early on, before Brian was off the road even some of the time. On their first album, 1962’s Surfin’ Safari, Usher has a co-writing credit on half (six) of the songs, including the hit “409.” A couple of those songs have Wilson-Usher-Love credits, including “409.” On their next LP, Surfin’ USA, Usher co-wrote one of the best non-45 early Beach Boys songs, “Lonely Sea.” Roger Christian co-wrote their 1963 hits “Shut Down” and “Little Deuce Coupe,” and Usher and Christian credits continued to pop up into 1964, including on “Don’t Worry Baby,” co-written by Christian.

Certainly it seems possible that rather than turning to other writers out of necessity when Love wasn’t available, Brian wrote with some others because of personal preference, or according to what he wanted to create depending on the song. When he retired from the road (occasional appearances and TV spots aside) at the end of 1964, Brian also certainly would have been around Love less, including in the Pet Sounds/Smile period, when the Beach Boys’ touring schedule included visits to Japan and the UK. Asher and Parks, however, certainly struck different lyrical moods than Love did, and according to some accounts, not with Love’s approval (especially on the Smile material Parks co-wrote).

Mike Love is not the most popular ’60s rock star, and has gotten a lot of heat from some writers and fans for not, in their view, supporting Brian’s most ambitious efforts. But he did contribute a lot to the group as singer and sometime lyricist, and according to one comment by Marilyn Wilson-Rutherford in the documentary, Brian did value Love’s place in the band, saying Brian thought Mike was the greatest frontman.

Bruce Johnston: Johnston has his share to say in the documentary, but he just wasn’t as important a part of the story as the other five principal Beach Boys. He has an interesting tale, however, about how he inadvertently negotiated his fee when he started playing with them on tour in 1965. Asked what he wanted for two weeks of touring, he asked for $250. It was thought he was asking for $250 a night, however, not for the whole two weeks. So he got $3000 instead of the $250 he was offering.

The Wrecking Crew: Sometimes the impression’s given that the Wrecking Crew played almost everything on the mid-’60s Beach Boys sessions. They certainly played on a lot of them, and they were certainly important, but their role might have generally been overestimated. In an archive interview in the documentary, drummer Hal Blaine says that Carl Wilson did play with the Wrecking Crew often on sessions, but also that he was the only one in the group who did (possibly Blaine was not counting Brian Wilson in this memory).

It’s all hindsight and quite possibly advice that would have been ignored at the time, but maybe Brian could have offered the other guys in the group at least some more instrumental input in the Pet Sounds/Smile era. Maybe they would have been just as happy to let the Wrecking Crew handle things, but it could have made them feel more involved, rather than being singers for what some consider more Brian Wilson projects than Beach Boys ones. Possibly that could have eased tensions down the road when Smile was taking a long time to complete (and never would get completed). After Smile broke down, the Beach Boys took over most of the instrumentation on the records anyway.

Another guy on the Wrecking Crew, Don Randi, has an interesting comment in the documentary. The influence of Phil Spector on Brian Wilson has been oft-covered, and Spector often used the Wrecking Crew too. Randi remarks that a key difference between Spector and Brian, however, was that Brian was always reinventing himself. They were both perfectionists, Love remembering how Brian had the group do backup vocals for “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” thirty times.

Smile: Much has been written about Smile, and how the band and especially Mike Love were not as supportive of Brian Wilson’s vision for the project as they could have been. A comment from an archive interview with Carl Wilson in the documentary serves as evidence that he wasn’t opposed to it. Carl acknowledged that Love didn’t think the lyrics were relatable, but also that he (Carl) loved it, praising how it was “so artistic and abstract.”

Charles Manson: There’s not a whole lot about Manson in the film, but Dennis Wilson’s interaction with the Manson Family isn’t skipped over. Love offers a cutting one-liner about Manson: “I only met the guy once, and that was enough for me.”

The Beach Boys Are a Group, Not Brian Wilson: One point the surviving Beach Boys make in the documentary, and one with which I’m in general agreement, is that while Brian Wilson was the most important member of the group, the Beach Boys were very much a group with individuals who made strong contributions, not Brian Wilson and sidemen. Love sees this as an issue for both the rest of the band and Brian, stating, “The problem was, Brian was being hailed as a genius, but there was no credit for the rest of the band…it might have been a little bit easier for Brian to handle the genius label.”

Adds Bruce Johnston, “I’m president of the Brian Wilson fan club. But the musicality of every Beach Boy is essential. If we didn’t have the ability, we wouldn’t have been able to sing these parts. Brian was lucky to have our voices to sing his dreams.”

Marilyn Wilson-Rutherford has this melancholy note: Brian could do everything, musically. “But the other parts of life were hard for him.”

I’m teaching a seven-week non-credit course on the Beach Boys from June 18-July 30 at the College of Marin in Kentfield, CA. It will meet on Tuesday nights from 7:10pm-9:30pm, and can be taken both in-person and through Zoom. Concentrating on their best work in the 1960s, the course follows their growth from their early surf and hot rod anthems through their lyrical maturation with symphonic masterpieces like “Good Vibrations” and the Pet Sounds album. Besides exploring leader Brian Wilson’s phenomenal skills as a melodic composer and sophisticated studio producer, the group’s glorious vocal harmonies will also be highlighted through a wealth of audiovisual clips and instructor commentary. Registration info at https://marincommunityed.augusoft.net, for course #8221M/6361.