There was no problem filling up a list of 25 or so reissues, or at least issues of previously unreleased material, this year. Maybe to the disappointment of those who hope there will be a never-ending vault of “discoveries” or “rediscoveries” of work by obscure artists who are largely or wholly unknown even to devout collectors, the list is almost wholly comprised of pretty big names. True, these are mostly box sets (some containing much previously unissued or even uncirculated material); batches of tracks that were mostly or wholly unavailable; previously unreleased live recordings; more or less straight reissues of records that have been hard to get, or at least hard to get for many years; and themed compilations that mix long-easily available items with some rarities.

It’s not the like days of, say, 1983, when you could go to a top record store (themselves much thinner on the ground now than back then) and pick up LP reissues of acts that you’d never heard anything of in one go. If you brought a lot of cash, you could theoretically get interesting recent such albums (most though not all of them totally above-board in terms of kosher licensing) by the Misunderstood, the New Colony Six, the Other Half, the Merseybeats, the Creation, We the People, the Sheppards, and the Action in one day. If all those names sound kind of old hat to seasoned collectors/historians these days, I hadn’t heard a single track by any of them when I got the records 41-42 years ago (and only a song or two by Wanda Jackson, one of many such artists I could add to the list).

So we have a list populated by extremely familiar greats like the Yardbirds, the Doors, and David Bowie, and few unfamiliar acts. The Mystic Tide are one, gaining the #2 spot, but even their material was made available on reissues from the 1980s and 1990s, if not in as good a package. And there are not-terribly-famous names like Robbie Basho, the Idle Race, and Dadawah, though they have their sizable cult followings, as well as genuine obscurities on some of the various-artists compilations. But as the cliché might go, there’s still much to enjoy even with the preponderance of big names, whether unreleased/rare tracks or intelligent/completist compilations.

1. The Yardbirds, The Ultimate Live at the BBC (Repertoire). Is this four-CD set the ultimate collection of the Yardbirds’ BBC performances? The way the reissue business works, you shouldn’t bet on this being the last one. True too there have already been several collections featuring their BBC material (and going back more than 45 years, some bootlegs with BBC tracks). And if you’ve kept up with as much of that material as you could, as I have, you’ll already have about three-fourths of this compilation. That’s a conundrum about being a completist – the more complete the upgrade is, the greater the chance you’ll already have spent a lot of money on much of it in previous iterations, though those (presumably younger people) just getting into the group won’t have such a serious issue.

Still, the two dozen or so previously unreleased tracks include some highlights and even surprises. Chief among those are June 1965 versions of “Respectable” and “Pretty Girl,” both of which were on their debut album Five Live Yardbirds, recorded in 1964. But these BBC versions are with Jeff Beck, not Eric Clapton, who was on the live LP. Note how Keith Relf changes the lyric of “Respectable” from “she’s the kind of girl for me” to “she’s the kind of woman for me” at one point. The last verse of “Pretty Girl” suddenly lowers in key and is a bit slower. Was that deliberate, in which case that’s pretty avant-garde for an R&B cover?

Other previously unissued items of note include “Someone to Love Me,” recorded in studio versions but not issued until after they broke up; a March 1965 “Jeff’s Boogie” when it was still known as “Berry’s Boogie”; the Impressions cover “I’ve Been Trying” (one of two versions, the other having been previously available); and an unissued “Too Much Monkey Business” with Beck on lead instead of Clapton (again one of two versions, the other having been previously available). “Steeled Blues” might have been a relatively trivial part of the Yardbirds’ catalog as the instrumental B-side to “Heart Full of Soul,” but they did it three times on the BBC, and two of the versions here are previously unissued. And there’s “Rack My Mind,” a rewrite of Slim Harpo’s “Scratch My Back” (which is also here), though it’s on the lo-fi side. Then there are previously unissued versions of “I’m Not Talking” and “I Ain’t Done Wrong,” again accompanied by different versions that have already been released.

It’s true that some of these unissued versions that are multiples aren’t too interesting, like a “Happenings Ten Years Time Ago” that is actually the track from the 45 with a different vocal. As great as “Heart Full of Soul” was, five versions is a lot, even if two of them are unreleased. In common with most 1960s BBC cuts by British rockers, it’s rare that the songs also found on their studio releases were done better or with much variation on the radio sessions.

But there are some performances of special caliber, like a “Smokestack Lightning” (again: with Beck not Clapton!) with some improvisation not hear on the Five Live Yardbirds version. The two unreleased versions of “Evil Hearted You” closing disc two are perhaps their best BBC versions of any of their hit singles, with some incredibly quick licks from Beck. And for the many tracks that have been around the block before (sometimes several times), the sound is often notably improved.

There aren’t any tracks here with Clapton as no BBC sessions with him survive, but BBC recordings from 1967-68 when Jimmy Page was sole guitarist comprise all of disc four. Just one of these was previously unreleased, and it’s not one most fans are dying to hear, as it’s a second version of one of their unimpressive Mickie Most-produced pop singles, “Goodnight Sweet Josephine.” On the whole this disc isn’t up to the standard of the three Beck CDs (which include a few tracks when both he and Page were in the group), but there are some highlights. Those are two versions of their final B-side, “Think About It”; Page’s acoustic guitar showcase “White Summer”; and a pre-Led Zeppelin “Dazed and Confused.” Too bad they didn’t do “Glimpses,” the psychedelic workout from their Little Games LP, or the outtake “Knowing That I’m Losing You,” later reworked by Led Zeppelin into “Tangerine.”

The set’s dotted with interviews that are mostly brief and pretty uninformative, though there’s an interesting bit when, asked who the leaders are in the creative side of (presumably the pop business; the BBC interviewer mumbles), Paul Samwell-Smith quickly names Pete Townshend – and no one else. The annotation is very thorough, including details of sessions that don’t survive, and memories from drummer Jim McCarty and bassist-producer Samwell-Smith. The notes also clarify that “Love Me Like I Love You,” the mysterious bouncy soul-pop number heard twice, is a cover of an obscure American soul disc by the Wallace Brothers, though it’s been previously credited as a group composition. (The January 2025 issue of the UK monthly magazine Record Collector has my 14-page story on the Yardbirds, focusing on this compilation. It draws from extensive recent interviews with drummer Jim McCarty and bassist/producer Paul Samwell-Smith, as well as one with Graham Gouldman, who wrote several of the Yardbirds’ hits. Info on this issue, though not the story itself, is at https://recordcollectormag.com/cover-story/the-yarbirds-the-sound-of-the-future-still.)

2. The Mystic Tide, Frustration (Numero Group). The Mystic Tide were one of the best garage-psychedelic groups of the mid-1960s, and of those acts in that elite category, one of the most obscure. The Long Island group issued just five singles on tiny labels in 1966 and 1967, never making a commercial impact even on the small local level. A CD compilation of their work (plus some far more recent tracks recorded by guitarist and songwriter Joe Docko) appeared thirty years ago, but this LP-only anthology has better sound and far more comprehensive liner notes, including a few quotes from my own interview with Docko in the late 1990s. If raw compared to most bigger acts in both its production and performance, the best of these tracks mix tremendous ‘60s punk energy with intriguing, almost experimental raga-tinged psychedelia.

The title track, “Frustration,” is the best of these, using the still-novel approach of two simultaneously sung lead vocals with both different lyrics and different melodies. But the two-part instrumental “Psychedelic Journey” is up there in the raga-rock sweepstakes; “Mystery Ship” a supremely haunting psychedelic ballad not far from the aura of the Doors’ earliest excursions; “Mystic Eyes” (an entirely different song than the Them classic) a more basic eerie effort in the same vein; “I Search for a New Love” an enticing psych-popper with swirling harmonies and tempo shifts reminiscent of the Soft Machine’s 1967 demos; and “You Won’t Look Back” another of the moodily ethereal tunes that was among the Mystic Tide’s strengths. Docko was a skilled and adventurous Indian-tinged psychedelic guitarist who could play both furiously and delicately. The earliest Mystic Tide singles are more basic British Invasion-inspired outings, but still enjoyable and not run-of-the-mill for primitive teen efforts. Also here is the sole unreleased track of theirs that has been unearthed (previously issued on 1994’s Solid Ground compilation), which like the early singles isn’t as good as their peak work, but is worth hearing.

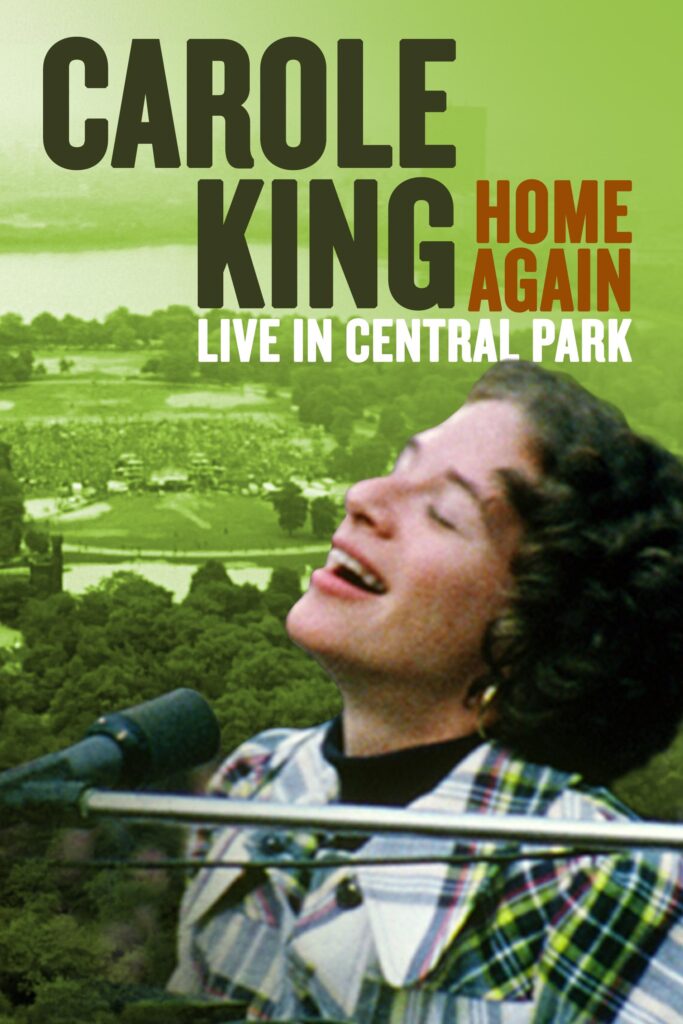

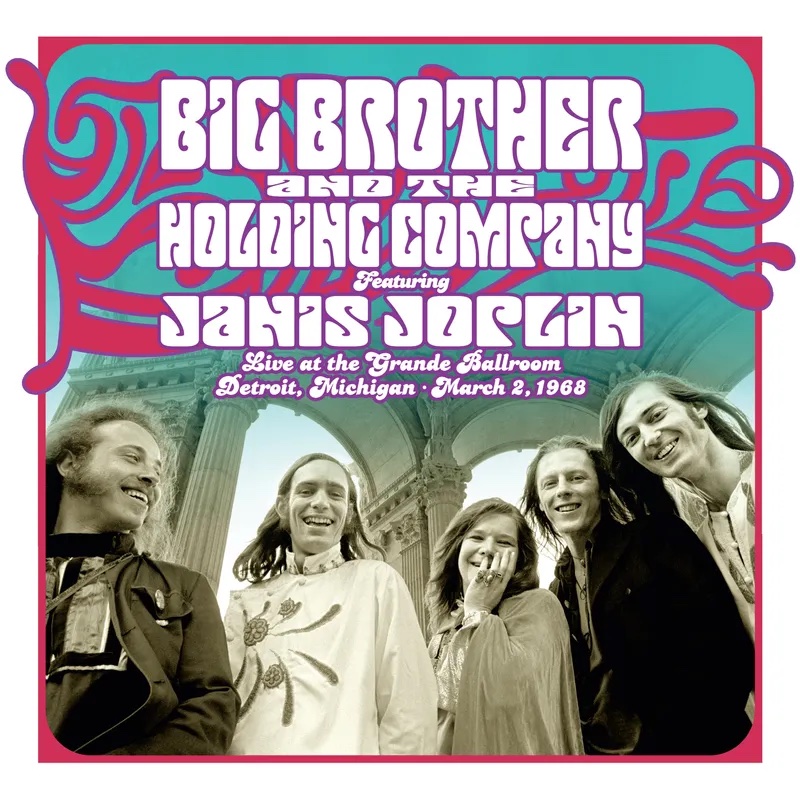

3. Big Brother & the Holding Company, Live at the Grande Ballroom Detroit, Michigan: March 2, 1968 (Columbia/Legacy). Before this release, there was already a fair amount of live 1968 Big Brother available, most notably a full CD of Winterland tapes from mid-1968, and another full CD of the group at the Carousel Ballroom in San Francisco in June of that year. Two of the tracks here (“Catch Me Daddy” and “Magic of Love”) are on the expanded Cheap Thrills. So I picked up this Record Store Day special as a completist, but it really is good and worthwhile. The band plays with fire, Janis Joplin sings with her habitual fire, and it includes some of their most popular tunes—“Piece of My Heart,” “Combination of the Two,” “Down on Me,” and “Ball of Chain.” And some of their better lesser known items, like “Coo Coo,” “All Is Loneliness,” and those two songs that didn’t make their two LPs with Joplin, “Catch Me Daddy” and “Magic of Love.” The sound is very good, and despite some comments that have been made by the MC5 claiming they killed Big Brother as their opening act, the audience seems quite appreciative.

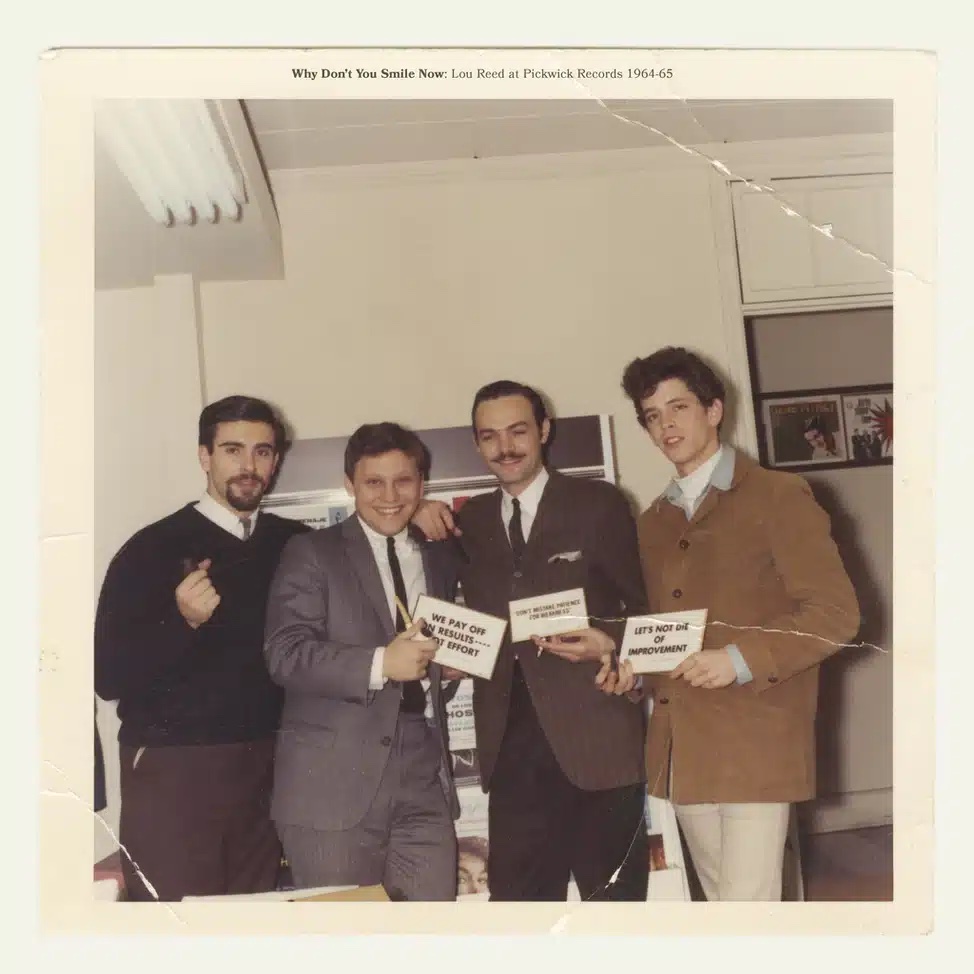

4. Various Artists, Why Don’t You Smile Now: Lou Reed at Pickwick Records 1964-65 (Light in the Attic). To qualify the high ranking of this compilation, I need to disclose that I wrote the 10,000-word essay in the liner notes. This is also a case where the historical interest of the material, and my particular interest in it, vaults it to a higher position than some releases where the skills of the performers (other than Lou Reed), like the Doors and David Bowie to take a couple examples, are obviously superior. This gathers 25 songs Reed co-wrote, or quite possibly co-wrote, during his strange stint as a staff songwriter at the budget Pickwick label from about fall 1964 through mid-1965. He did sing lead vocals on four of these tracks, and likely played guitar on these and some others. On the majority, however, he shares songwriter credits (usually with Pickwick staffers Terry Philips, Jimmie Sims, and Jerry Vance) on obscure mid-‘60s songs sung by other artists. All of the cuts showed up on either rare flop singles and exploitation budget compilations, and one, the Beachnuts’ “Sad, Lonely Orphan Boy,” was previously unreleased.

I’d heard all of these except “Sad, Lonely Orphan Boy” before, and the ones on which Reed sings have shown up on bootlegs for about half a century. Still, it’s good to have the best of Reed’s Pickwick efforts (some of the worst aren’t here) assembled in one place on a legitimate release, with good packaging complete with a Lenny Kaye foreword and illustrations (including a previously unpublished color one of Lou with Pickwick staff on the cover). Reed’s raw talents are readily apparent on the four songs he sings – the Primitives single “The Ostrich”/ “Sneaky Pete,” the Roughnecks’ “You’re Driving Me Insane,” and the Beachnuts’ marginally more conventional “Cycle Annie.” Otherwise he and the Pickwick writers were obviously trying to emulate trends of the day like surf music, the Four Seasons, Motown, and New York girl groups. Compared to the Velvet Underground, or even the Primitives/Roughnecks tracks, they’re surprisingly poppy, and sometimes lightweight and formulaic.

What’s most pleasantly surprising about this comp, however, is that with the selection and sequencing, it’s a pretty enjoyable listen even aside from its value to Reed historians. Some of the tracks are good rarities by any standards, especially Robertha Williams’s Shangri-Las soundalike “Tell Mamma Not to Cry.” If some of the other tunes are almost ironic in their offhand derivativeness, they’re often executed in a fun fashion that don’t take themselves too seriously, sometimes deftly using their audible influences, like the daughter-of-Martha & the Vandellas backup vocals on Beverley Ann’s “We Got Trouble.” On a more serious note, the odd guitar tuning on “The Ostrich” was instrumental in firing John Cale’s interest in what Reed was doing at Pickwick and joining him in the touring version of the Primitives, as well as co-writing one of the better songs here with Reed and others, the All Night Workers’ “Why Don’t You Smile.” There’s much more I could say about these tracks, but for that, you’ll have to read my actual liner notes to this anthology.

5. The Doors, Live at Konserthuset, Stockholm September 20, 1968 (Rhino). As if to validate the “Jim’s not dead” chant heard from the audience at some screenings of Doors films, it seems like there’s a “new” Doors album every year, much as there’s a “new” Jimi Hendrix album every year. Of course, these new releases were recorded more than fifty years ago, as the estates trawl ever more deeply in the vaults. Such is the case with this double CD of the Doors live in Stockholm, a Record Store Day release (also issued on vinyl) that wasn’t too hard to get if you didn’t actually go to a record store that day, though it’s already getting harder – The Doors’ Official Online Store had sold out of the CD version by early May. While this isn’t the absolute best live Doors of the many concert recordings by the band now available, it’s one of the relatively few of those in good sound that was made before 1969. And while it has some numbers that show up in many, maybe too many, versions on other releases—“Five to One,” “Back Door Man,” and “When the Music’s Over,” for instance—there are also a few that are on hardly any or even none others.

Among them, and thus among the highlights, are “Love Street,” “You’re Lost Little Girl,” and “Wild Child.” It’s evident, maybe inadvertently, that the Doors weren’t used to doing these in concert—Jim Morrison seems to skip and stumble over a few lines in “Love Street,” and Robbie Krieger doesn’t execute the guitar solo in “You’re Lost Little Girl” very well. Also, there seemed to be a mike failure for the early show’s rendition of “When the Music’s Over,” where the vocal can barely be heard for a good chunk of the track. That’s not such a big deal considering how many other versions of this song are available—in fact, there’s another one on this CD, from the late show. As for some other tunes that don’t show up too often on live Doors recordings, there’s “Love Me Two Times” and “The Unknown Soldier,” both played without mishaps, and “Money,” though these kinds of rock’n’roll/soul/blues oldies covers were never the group’s forte.

Standbys like “Light My Fire” (twice) and “The End” are also here. Although Morrison was sometimes not in good shape during this 1968 European tour—and wasn’t even present with the other Doors at one as he was too wasted to perform—he seems fully sober and in top form here. As do the band as a whole, making this one of the best live Doors releases. And while the crowd seems kind of subdued—not such a bad thing, as it helps the music come through entirely clearly—it goes wild at the end of the first show, with a couple minutes of clapping/stamping/whistling.

6. David Bowie, Rock’n’Roll Star! (Parlophone). It’s not so obvious from the title, but this is basically a superdeluxe edition of Bowie’s most famous album, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. You’ll need a Blu-Ray player to actually hear the original album on the Blu-ray disc, but the real attraction is the rest of the set, comprised of five CDs of material not on the album. That includes numerous demos, rehearsals, and outtakes, along with a bunch of 1972 BBC radio, TV, and live recordings. There are also the early-‘70s singles credited to Arnold Corns that were more or less Bowie under a different name, and the kind of less essential alternate/new mixes which pepper these deluxe productions, by Bowie and others. Twenty-nine of the tracks are previously unreleased, which isn’t a huge percentage from such a big package, especially considering some of the unreleased items are mix variations. Still, there’s something to be said for having most/all of the extra-LP stuff from shortly before/during/shortly after its recording in one place, even if the $100+ price tag isn’t cheap.

There isn’t much in the way of previously unheard songs, especially considering that some of these evolved into more familiar tunes, like the San Francisco hotel recording of “So Long 60s,” part of which evolved into “Moonage Daydream.” The chief interest is hearing how much honing and refining went into the songwriting and arrangements over the course of a year, with even the basic demos forming much of disc one making it obvious the compositions held great promise. All of this is enjoyable no matter what the circumstances or recording quality (which is mostly very good), and by the time you get to actual or close-to Ziggy Stardust tracks, they can seem kind of slick, in part because of their over-familiarity.

There are some songs that aren’t from the final Ziggy running order, including live/radio/TV performances of Hunky Dory material, “Space Oddity,” and the Velvet Underground’s “White Light/White Heat” and “I’m Waiting for the Man.” There are also the non-LP 45 tracks “John, I’m Only Dancing,” a big UK hit, and the B-side cover of Chuck Berry’s “Round and Round.” Bigger surprises are the almost country-influenced, acoustic-flavored outtake “It’s Gonna Rain Again,” and a pre-Pin Ups version of “I Can’t Explain.” As with other Bowie superdeluxe productions to date, there’s a big (112-page) hardback book with lots of info and pictures, helping to offset the cost if you already have much of the music.

7. The Rascals, It’s Wonderful: The Complete Atlantic Studio Recordings (Now Sounds). It’s not every year I write 10,000-word liner notes for more than one reissue, and need to make “full disclosures” when I include them on my year-end list. Here’s another case, though, as I wrote notes of that length featured in the 60-page booklet of this box set. The seven-CD box does indeed include everything the Rascals released while they were with Atlantic between 1965 and 1971. That means all seven of their albums (the first four in both their mono and stereo versions) and a few non-LP singles, and while there was a limited edition Rascals-Atlantic box, this adds fourteen previously unreleased tracks. Some of those are alternates, but they include some notable items like a 1966 recording of their version of the Knight Brothers’ “Temptation’s Bout to Get Me” (which they’d remake in 1969 for official release); the nice 1966 outtake “Marryin’ Kind of Love,” co-written by Doc Pomus; and the nice folky demo “Let Freedom Ring,” written by Rascals singer Eddie Brigati.

Much has been written in praise of the Rascals’ mix of rock and soul, and again for more of mine, you’ll need to read my extensive liner notes. It’s true many of their highlights were on singles, but they had some fine B-sides and album tracks. And while their first two to three years saw their best recordings, their later and less popular releases weren’t devoid of worthwhile efforts. They’re all on this collection, which also includes some detailed track notes by compiler Alec Palao.

8. Brian Auger’s Oblivion Express, ’70 Super Pop Montreux (Repertoire). Although he remains most known for his stint with Julie Driscoll and the Trinity, organ virtuoso Brian Auger’s time in that band was relatively brief, and by the 1970s he’d launched a different group. This 56-minute disc has the Oblivion Express’s set from the Casino Kursaal in Montreux, Switzerland on October 17, 1970. Purely from a historical perspective, it’s valuable as these are the only known Oblivion Express recordings with original drummer Keith Bailey. They also predate the band’s Oblivion Express debut album by about half a year.

More than documenting the group in its earliest stage, however, this is a pretty dynamic set that shows them fairly successful in their intention to bridge rock with R&B and jazz. The sound quality’s just a tad below what might have been expected on an official concert release at the time, and the largely instrumental material mixes Auger originals with covers of compositions by Herbie Hancock, John McLaughlin, Sly Stone, and Eddie Harris.

Auger’s not such a hot singer when he takes vocals, but as the focus is on his thick and forceful organ, as well as the fairly hot guitar-bass-drums backup, that’s not such a big deal. With a couple longer exceptions, the songs hover around the five-minute mark, largely avoiding the tedium of extended prog-rock workouts.

The highlight of the show—and maybe the highlight of Auger’s non-Driscoll-affiliated career—is the riveting, joyous “Pavane.” You might never guess it’s an adaptation of a classical piece by Gabriel Fauré, as it’s jammed with compelling riffs and dramatic, suspenseful melodic turns. Some other British organists, especially Keith Emerson and Rick Wakeman, got attention for rocking up the classics, but Auger certainly proved capable of doing so here, and doing so well. Drilling down deep, this might not be quite as good as the killer frenetic rendition he managed with the Trinity at the Bilzen Festival in Belgium 1969 (as seen in footage of that performance), but it comes close.

The release bolsters Auger’s credentials as one of the more innovative British keyboardists of the period, and perhaps the most jazz-influenced one who just about fell into the rock category. Repertoire put out another CD at the same time of Auger with Driscoll and the Trinity at the same venue on June 14, 1968, which is reviewed separately. (This review will also appear in a future issue of Ugly Things.)

9. Nina Simone, Blackbird: The Colpix Recordings (1959-1963) (SoulMusic). Even at the beginning of her career, Nina Simone was an artist as prolific as she was eclectic. In her four years on Colpix she issued eight albums and some non-LP singles, as well as making a good number of recordings not released at the time. All of those albums, in sleeves reproducing the original artwork and liner notes, are on this eight-CD minibox. It adds 29 bonus tracks she cut during these years, some of which didn’t come out until decades later.

Colpix wasn’t Simone’s first label, as she done a prior LP for Bethlehem with her hit “I Loves You Porgy” (the version on this box is a later remake). Arguably she might have overextended herself with her sheer volume of Colpix material, adding up to 107 tracks. These included four live albums, a Duke Ellington tribute LP, and Folksy Nina, “entirely composed of folk ballads and blues” as the original liner note declared, although it sounds about as typically Simone as most of her other Colpix longplayers.

You’d have to be an intense collector to already have the bonus cuts, some of which only came out on 1966’s With Strings (recorded during the Colpix years), UK expanded CD editions, and rare non-LP 45s. This compilation does completists quite a service by rounding all of those up, adding a few to each disc as extra tracks. Some of them are prime Nina, like the ten-minute live version of “Work Song”; the “Hit the Road Jack” answer single “Come on Back Jack”; the haunting, almost Mediterranean “Golden Earrings”; and the spare, spooky 1963 non-LP B-side “Blackbird,” which gives this anthology its name.

While Simone would cast her net even wider in the decade after leaving Colpix, it’s no exaggeration to state that even at this early stage, she was as stylistically eclectic as any performer. There was straight jazz, orchestrated pop ballads, a stab at pseudo-soul with “Come on Back Jack,” gutsy blues-jazz, movie themes, a bit of gospel and children’s music, traditional folk songs (including “House of the Rising Sun”), and what would later be called “world music” with songs in Hebrew and “Theme from Sayonara.” There wasn’t rock’n’roll, but there was almost everything else, especially when you consider the shades of classical music heard in her piano playing, she originally having aspired to be a classical pianist.

Range isn’t synonymous with quality, of course, and her vast repertoire almost ensured that not every fan would like everything, or at least not like everything about as much. There’s too much quaint’n’dainty balladry and Tin Pan Alley, especially when there’s orchestration and choral backup voices. She wrote hardly any of the material, though she did get a co-writing credit for “Blackbird.” The Ellington tribute wasn’t the best showcase for her originality, though even there, she excels on piano on the swinging instrumental “Satin Doll.”

For those like myself that favor her less standard approaches, these sides are best when she goes afield from pop-jazz into bluesier stuff and, at times, pieces that were pretty out there for a singer more apt to be filed under the pop or jazz sections than anywhere else. Highlights in that regard include Oscar Brown, Jr.’s “Rags and Old Iron,” “Trouble in Mind,” the folk-bluesy “Little Liza Jane,” “Black Is the Color of My True Love’s Hair,” “Gin House Blues,” and “Sinner Man.” The Hebrew songs aren’t novelty items; they’re among the most exotic and passionate pieces, particularly “Eretz Zavat Chalav U’dvash.” And some of the ballads are among her peak Colpix efforts, particularly “Wild Is the Wind” (perhaps the Simone interpretation that inspired David Bowie to record it on Station to Station, though she also did a version on the 1966 album Wild Is the Wind) and “Willow Weep for Me.”

As good, if erratic, as her Colpix output was, it’s missing some elements that would take her to a higher level when she moved to Philips for her next (and best) batch of albums in the mid-1960s. While never a straight “soul” singer per se, there was more soul in what she did at Philips, even as she kept encompassing the same styles as she had at Colpix and then some. Of course those included her magnificent civil rights (“Mississippi Goddam”) and feminist (“Four Women”) compositions, but also the original version of “Don’t Let Me Misunderstood,” covered to classic effect by the Animals. There was also “See-Line Woman,” covered by the Easybeats; her take on “I Put a Spell on You,” whose “I love you” refrain influenced the Beatles’ “Michelle”; and remakes of a few songs from her Colpix records, like “Work Song” and “Sinner Man.”

While her Philips stint also had its share of inconsistency, it showed a bolder evolving artist at her peak, as did some of her slicker work for RCA in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Those who don’t want or need to immerse themselves in the entire early Simone discography will be better off with compilations like Rhino’s double CD Anthology: The Colpix Years. For those who want more, though, this box is exemplary in its thoroughness. (This review previously appeared in Ugly Things.)

10. Melanie, Neighborhood Songs (Neighborhood/The Wintergarden). It’s hard to believe a collection of previously unreleased vintage Melanie could be more comprehensive than this six-CD set. There are demos, live performances, radio broadcasts, and studio outtakes spanning the mid-1960s to the late 1970s (a snippet of her as a child performer on TV in 1951 isn’t worth detailing). The three discs covering the mid-1960s to the early 1970s (most of those tracks spanning 1968-72) are the ones really worth hearing, as those were during her absolute prime. Usually they present her in a solo acoustic folky context, with just a few that have a full band backup or studio orchestration. It would have been nice to have more cuts with full arrangements; some of these, like the versions of “Ruby Tuesday” and “Beautiful People” from a July 1971 concert, are really nice and different from the standard ones. The plain accompaniment for much of the material does tend to feel somewhat monochromatic in bulk, and make the songs themselves seem less wide-ranging.

At the same time, these performances are extremely intense, in a good way, and invigorating to hear even if the songs don’t stand out as much (or as much from each other) in this context as they do on her studio releases. Some of them get almost frighteningly intense in their penetrating vocals and furious guitar strumming, especially a 1968 home demo of “Ruby Tuesday.” The liner notes could have been more helpful at pinpointing songs that didn’t appear in studio versions at the time, but there are some, along with versions (sometimes multiple versions) of her more celebrated compositions, like “Beautiful People,” “The Nickel Song,” “What Have They Done to My Song, Ma,” and “Peace Will Come.” There are four versions of “Ruby Tuesday,” and the October 1969 Hershey, Pennsylvania broadcast version of “Candles in the Rain” is quite different, and more somber, than the one on the hit single.

On the rest of the set, there’s an entire disc of 1975 studio recordings and another of 1975 concert tapes, with another CD of 1976-79 items. While these observations could be noted of many performers from the time who passed their peak and cultural moment, they’re too prone to mainstream production, too-long arrangements (especially the ill-advised drawn-out one of the Seekers’ “I’ll Find Another You”), and compositions that aren’t as impressive. Some of the mid-to-late 1970s material is certainly okay in a moderately pleasant way, but it’s the earlier stuff that’s more inspired and notable. It’s unfortunate this doesn’t include her rare pair of 1967-68 Columbia singles, which haven’t been reissued to my knowledge. And while the liner notes are extensive and perhaps overly appreciative, they could have been clearer as to the song’s histories and differences between what’s heard on the box and the more familiar versions. Overall, however, this helps give Melanie her due as an underrated performer who’s sometimes been unfairly scorned, even if the box, like much of even her best work, is uneven in quality.

11. Buffalo Springfield/The Byrds, Live at the Monterey International Pop Festival (Monterey International Pop Festival Foundation). This vinyl double LP Record Store Day release devotes one disc to Buffalo Springfield’s set at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival, and the other disc to the Byrds’ set at the same event. Seven of the eight Byrds songs (all except “I Know You Rider”) came out in 1992 on a Monterey Pop box; the eight Buffalo Springfield songs haven’t come out anywhere, to my knowledge. As these are two of my favorite groups, and the Springfield material (and one of the Byrds tracks) were previously unreleased, why doesn’t this rank higher on this list? Neither of the groups played that well, though it carries a lot of historical interest.

One reason Buffalo Springfield might not have been as good as many might have hoped is that Neil Young had left the band for a while at the time of the festival, with David Crosby sitting in. In common with the Byrds’ set, the Springfield’s sounds a little rushed and ragged, despite their reputation as having been a white-hot live outfit. Some of that could be due to Young’s absence, but the drumming in particular isn’t very impressive, and nor is the recording quality on either the Springfield or Byrds disc, though it’s okay.

Besides three of their most familiar songs (“For What It’s Worth,” “Rock and Roll Woman,” and “Bluebird”), Buffalo Springfield’s set is of particular note for including a Richie Furay composition (though with drummer Dewey Martin on vocals), done in a soul-rock arrangement with not-to-easy-to-understand lyrics, that didn’t make their albums, “Nobody’s Fool,” though it got onto Poco’s first LP. There’s just one Young song, “Nowadays Clancy Can’t Even Sing” (with Furay on lead vocals), though it’s interesting to hear versions of “A Child’s Claim to Fame” and “Hung Upside Down” that predate the release of their second album by about four months. Most valuable of all is a performance of “Pretty Girl Why,” which wouldn’t come out until their third and final album – both for its rarity and for a rendition that’s fairly good and among the better tracks on the Springfield disc, though no match for the studio version.

The Byrds’ set has been in circulation for quite a while, save for the cover of the folk standard “I Know You Rider,” which the Byrds did record in the studio, but only as an outtake. They sound less together than Buffalo Springfield, which is to say, not very together. Both acts, in fact, had pretty imperfect drumming. But the Byrds’ harmonies and general tightness are far from exemplary, though the song selection is interesting, with cuts from their first four albums (none hits except “So You Want to Be a Rock’n’Roll Star”) and, most unusually, the non-LP single “Lady Friend.” You also get Crosby’s annoyingly pompous comments about LSD and the JFK assassination. The Byrds, as great as their records were in the mid-1960s, did not have a reputation as a good live act, and this disc unfortunately bears this out.

This double LP also makes a case for why neither the Byrds nor Buffalo Springfield made the classic Monterey Pop documentary, though some footage of both made the expanded DVD version. There’s not much in the way of interesting text on this release, but it does reprint the official invitations to both groups; print some quotes about Monterey and the acts from band members and peers; and reproduce the tape boxes with the recordings.

12. Neil Young, Early Daze (Reprise). While quite a few artists—like the Doors, Jimi Hendrix, and Frank Zappa elsewhere on this list—are keeping a pretty active release schedule of vault material, Neil Young might be putting out more than any top-tier act. The one of most interest to me in 2024 was this compilation of 1969 tracks. Like some and maybe most of his other archive productions, it’s a bit frustrating no matter what level of fandom you maintain, mixing genuinely unreleased versions, different mixes, and some items that have appeared on previous records, though those are rare or low-profile. Crazy Horse backs him on all of these, and while some of the songs didn’t come out at the time in any form or only on Crazy Horse discs, by this time most or all of them are familiar to most people who keep up with Young’s catalog. Too, the better known tunes generally they don’t vary enormously from those familiar versions, though “Down By the River” has alternate vocals and “Helpless” is, as you’d expect, relatively harder rocking than CSNY’s arrangement.

Still, as a listen and the kind of thing that used to show up on bootlegs but is now being made available in better sound and packaging, it’s nice to hear. Even if you know “Dance Dance Dance,” “Look at All the Things,” and “Come on Baby Let’s Go Downtown” were done by Crazy Horse on their 1971 self-titled album, it’s cool to hear Young’s versions. Completists will appreciate hearing the single mono mix of the most famous song (other than perhaps “Down By the River”), “Cinnamon Girl.” And “Winterlong,” another version of which appeared almost five decades ago on Decade, is represented by a previously unreleased version; “Wonderin’,” done with a much different arrangement more than a decade later, sounds better with a characteristically 1969 Young sound. While not exactly an alternate version of Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, it’s kind of a good supplement to how Neil sounded on that album. It’s marginal enough when judged against Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, though, that it doesn’t rank too high on this list, also considering a couple of the best songs (“Cinnamon Girl” and “Birds”) are represented by rare/alternate mixes rather than more significant variations.

13. Julie Driscoll, Brian Auger & the Trinity, Live at Montreux 1968 (Repertoire). A fair amount of live/BBC Driscoll/Auger/Trinity has circulated unofficially and on gray-area releases. But to my knowledge, this 65-minute document of their performance at the Montreux Jazz Festival on June 14, 1968 is the first totally above-board live document of the group. As with a simultaneous release on Repertoire of a 1970 concert by Brian Auger’s Oblivion Express at the same venue (reviewed separately), the sound quality’s very good, almost but not quite 100% of what might have been considered for an official concert LP back in the late 1960s.

This ensemble—just a quartet despite their unwieldy name—had just reached their peak in spring 1968 when their cover of Bob Dylan’s “This Wheel’s on Fire,” at that point not available on a Dylan release, reached the Top Five in the UK. Oddly, that song isn’t on this set, which is both rewarding for what it has, and frustrating for what it doesn’t. Most crucially, only half of the twelve tracks have Driscoll vocals. The Trinity often performed material without her on stage, but the songs on which she sang were the definite highlights.

This is too early to catch more adventurous/progressive parts of this eclectic soul-rock-jazz-psychedelic act’s repertoire, like the “Road to Cairo” single and their Streetnoise album. But this does feature a couple highlights of their more soul-rock-oriented sound with their distinctive take on “Season of the Witch,” here running eight and a half minutes, and a rousing cover of Aretha Franklin’s “Save Me,” on which David Ambrose’s driving bass really excels. Of particular interest to Driscoll fans, jazzman Johnny Griffin’s “Soft and Furry” (apparently based on singer Eddie Jefferson’s version) wasn’t on the Trinity’s official releases, though a good live cover of the tune kicks off their set.

After a half dozen satisfying Driscoll-fronted cuts, organist Brian Auger takes the spotlight on instrumentals of varying if generally impressive quality (though he does sing Mose Allison’s “If You Live”). His speedy riffs are to the fore on Booker T. & the MG’s’ “Red Beans and Rice,” and he slows to a funkier pace on a quirky cover of “A Day in the Life.” The jazzy bopper “Along Came Zizi,” which he wrote for a sister-in-law, isn’t available in any other version; indeed, Auger had forgotten it even existed.

Yet the sole other Auger original, “Goodbye Jungle Telegraph,” outstays its welcome as the ten-minute piece gets into noisy experimental passages, complete with whooping pennywhistle-like swoops, that veer into self-indulgence. As that’s the last track on this CD, it’s easily enough avoided in favor of the tighter, more disciplined tracks that precede it. (This review will also appear in a future issue of Ugly Things.)

14. Jackie DeShannon, Nothing Can Stop Me: Liberty Records Rarities 1960-1962 (Ace). So much DeShannon has been reissued, much of it by Ace, that it’s hard to believe much could have remained in the vaults. There was some, however, and sixteen of these twenty-four tracks were previously unreleased, while the others aren’t exactly common fare. Even DeShannon fans, and I’m one, should nonetheless be aware that with a couple exceptions this doesn’t show her at her best, even if you’re just considering her pre-1963 work.

About half of these were recorded in 1961 for a Ray Charles cover album to be titled Hits of the Genius, which was canceled after getting scheduled for January 1962 release, at least in part because Bobby Darin put out a Sings Ray Charles album around the same time. It would be more interesting to hear DeShannon sing original material, and that’s not the only drawback. Although she digs into the Charles repertoire (much of it well known tunes like “I Got a Woman” and “What’d I Say,” with the lyrics sometimes changed to become more appropriate as sung by a woman) with gusto, she tends to over-sing these, or at least overemphasize the rougher side of her vocals, as good as those could be in the right context. A few of these tracks did come out, but most were unissued until this compilation.

The second half of this CD presents tracks that would not have been on Hits of the Genius, though a couple of these (“Nobody But You” and “Fool for You”) were actually Charles compositions. A couple did come out on rare singles, and there are a couple alternate takes of two other tunes that also did find release, but most of it’s previously unreleased. The standouts are the two songs, alas, that are the least rare, and have appeared on other compilations: the fetching “I Won’t Turn You Down,” which mixes teen idol and girl group sensibilities, and the rowdy “Baby (When Ya Kiss Me),” which at least is presented as an alternate take.

Although all of the songs save the Charles covers and “I Won’t Turn You Down” were written by DeShannon (sometimes with Sharon Sheeley), none of the others are of the same caliber, though they’re not bad early-‘60s pop-rock. Some are better than others, like the perky “I Don’t Think So Much of Myself Now” and the slightly bittersweet “Wishin’ Won’t Get It,” and “Stand Up and Testify” has a lot of gritty energy, if not too special a tune. With typically good Ace annotation, this is a reasonably interesting release for DeShannon completists, but not even among the best of the rarities that would be good to have on official releases, those being the numerous demos she recorded for her Metro Music publisher in the early-to-mid-1960s.

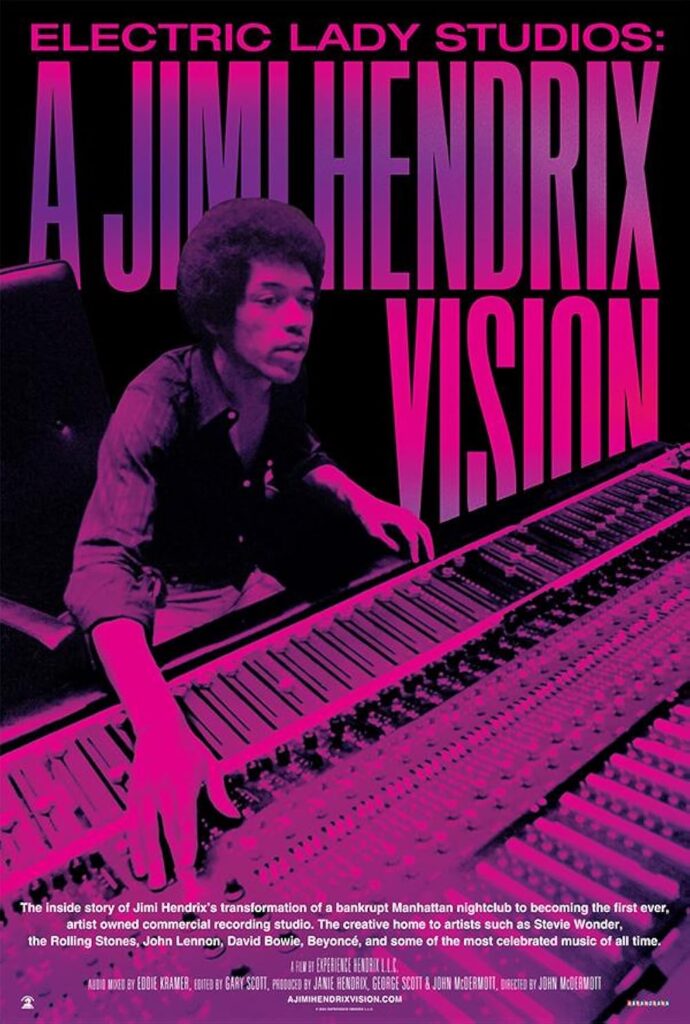

15. Jimi Hendrix, Electric Lady Studios: A Jimi Hendrix Vision (Experience Hendrix). This four-disc set wasn’t just released in conjunction with the film documentary of the same name. It actually includes the documentary, as one of the four discs has it on a Blu-ray. The other three discs are CDs of recordings, almost all of them previously unreleased, Hendrix did at Electric Lady in mid-1970, though a few of them built on early recordings done elsewhere as early as late 1969. Since the Electric Lady Studios film did play in some theaters, I’m giving it a separate review in this blog’s year-end roundup of music history films. This review will concentrate on the music on the three other discs.

Most of these songs are familiar from their appearances in different versions on other posthumous Hendrix releases going back to the early 1970s. In common with the more recent such releases, this is dominated by alternate versions/takes, and sometimes alternate mixes, of songs that have appeared elsewhere, sometimes numerous times, and sometimes dating back to shortly after Jimi’s death. It’s valuable for dedicated Hendrix fans and collectors, but might be hard to recommend to others, even others who like Hendrix a lot. Some of the differences between the versions they might already have in their collection are slight, though Hendrix authority John McDermott’s liner notes make the differences clear. Even without knowledge of the other versions, this wouldn’t stand up as a whole with Hendrix’s best work, as a good number of the outings are jam-based meanderings, half-formed bluesy efforts, or just not in the league of his best compositions. The best (and usually) most famous songs are exceptions, including “Dolly Dagger,” the languid, pretty ballad “Drifting,” “Ezy Ryder,” and especially “Angel.”

The most notable track, at least if you’re on the lookout for what’s most unusual or least traveled, is the demo “Heaven Has No Sorrow.” With bassist Billy Cox supplying the only accompaniment, it’s lower-key and lower-volume than most of Hendrix’s repertoire, and has a nice reflective vibe and descending melodic lines. It’s a little unfortunate and mysterious it wasn’t developed more, since as Cox says in the liner notes, “It probably could have evolved into a pretty dynamic song, something along the lines of ‘Angel.’” Note that a couple of the more obscure songs, “Tune X/Just Came In” and “In from the Storm,” have some riffs similar to those used by Blind Faith in “Had to Cry Today.” The liner notes, besides having a lot of Electric Lady early history, feature some rare photos and memorabilia, including what seems like a proposed song list for a double LP drawn from this material, which has 26 songs.

16. Various Artists, Les Cousins: The Soundtrack of Soho’s Legendary Folk & Blues Club (Grapefruit). Les Cousins was the most famous British folk club from the mid-1960s through the early 1970s, hosting a huge number of performances in London’s Soho neighborhood. This triple-CD mini-box doesn’t have live performances recorded at the club; had any been made, some of those might have immense historical significance. But it does have 73 studio tracks from 1963-73 that ably reflect the wide range of performances and styles Les Cousins presented, also serving as a good overview of the British folk scene as a whole during its greatest decade, including a few US artists who played the club.

It would take a few paragraphs to list all the names of note heard on this anthology, from big stars (Donovan, Paul Simon, Cat Stevens) to major folk icons (Bert Jansch, Sandy Denny, John Renbourn) and vital acts who could venture well beyond the borders of standard folk forms (Nick Drake, Duffy Power, Davy Graham, Tim Hardin). Room’s made for artists who fall outside of what some might consider folk music, like Kevin Ayers, Third Ear Band, and the Picadilly Line, whose 1967 cut “At the Third Stroke” is more pop-rock than folk, even if Danny Thompson is on bass. It’s also one of the set’s highlights, and the liner notes’ description of their sound boasting a “strong flavor of psychedelic swinging London’s answer to Simon & Garfunkel” is fairly on-target.

For the most part, the bigger names—all represented by well-chosen and sometimes familiar cuts, like Hardin’s “If I Were a Carpenter,” Donovan’s “Sunny Goodge Street,” and Denny’s “You Never Wanted Me”—outshine the more obscure names by a sizable margin. Other than the Picadilly Line’s contribution, the choicest rarities include the biting pop-folk of “Get the One I Want To” by Beverley (aka Beverley Martyn), previously only available on a Record Store Day vinyl release; the Levee Breakers’ perky jugbandish “Babe I’m Leaving You,” a 1965 single featuring the same Beverley; Alex Campbell’s mournful “Been on the Road So Long,” from a 1965 single (and perhaps better known as done by Sandy Denny); and Sam Mitchell’s “Leaf Without a Tree,” one of the darker and bluesier selections, from a guy who’d later play on Rod Stewart’s Gasoline Alley and Every Picture Tells a Story.

Naturally not every Les Cousins performer of value could be included for space and licensing reasons, among them some mentioned in Ian A. Anderson’s lengthy liner notes, such as Van Morrison, Sandy Bull, and Stefan Grossman. If you’re looking for the kind of names not every big fan of UK ‘60s folk has in their collection, there are a fair number of those—it’s doubtful many people have music by Gerry Lockran, Andy Fernbach, Tom Yates, and Mudge & Clutterbuck in the same home. Even Steeleye Span fans might not know of “Adieu Sweet Lovely Nancy,” recorded by future members Tim Hart & Maddy Prior on a 1968 LP.

A good number of the tracks, especially by the more traditional-oriented artists, have a low-energy air that keeps this from being the most exciting listen. When something like Davy Graham’s middle eastern-tinged instrumental “Maajun” comes on, that does get the blood rushing faster, as do Paul Simon’s “I Am a Rock” (from his 1965 UK solo LP) and even more ordinary but relatively high-voltage items like Julie Felix’s “The Young Ones Move.” Among the several Cherry Red comps that focus on the UK folk and folk-rock of the era, however, this could be the most eclectic and all-encompassing, especially as it features other notables who couldn’t fit into the preceding paragraphs, from the Incredible String Band and Jackson C. Frank to the Strawbs and Roy Harper. (This review previously appeared in Ugly Things magazine.)

17. The Idle Race, Live on Air 1967-1969 (London Calling). Mostly known, if at all, for including Jeff Lynne before he joined the Move and then Electric Light Orchestra, the Idle Race played a very light brand of Beatlesque pop-rock in the late 1960s, sometimes with touches of psychedelia. In that regard they were similar to the Move, though not as good and considerably more lightweight. Never getting hits in the US or their native UK, the material from their two albums with Lynne hasn’t been too hard to get, in part because Lynne’s membership ensured there were reissues. This compilation has 27 songs from seven of their BBC radio sessions, mostly in decent sound, though some tracks fall a little below that and are incomplete. In common with many BBC sessions for acts huge or cult, the versions of the songs also found on their studio releases aren’t too much different as performed for the radio. Most of the songs were on their studio releases, and whether from their two albums or non-LP singles, the majority of them are represented by radio renditions here.

That leaves just a few rarities, inasmuch as being tunes they didn’t release at the time. These include cover versions of Moby Grape’s “Hey Grandma,” the Doors’ “Love Me Two Times,” and “Born to Be Wild,” and while they testify to the band’s knowledge of period US music—much as the many covers by the Move did—they’re not very interesting. Far more obscurely, there’s a version of “Blueberry Blue,” by the Lemon Pipers of “Green Tambourine” fame that even those with some knowledge of the Lemon Pipers might not recognize right away. The same goes for the Sopwith Camel’s “Frantic Desolation.” There are pretty annoying radio jingles between some songs, but it doesn’t seriously affect the quality of a release that will please intense Idle Race fans and late-‘60s British rock collectors, though the liner notes are just reprints of 1967-69 press stories about the band.

18. Dadawah, Peace & Love Wadadasow (Doctor Bird). In the late-‘70s book Rock Critics’ Choice: The Top 200 Albums, Lenny Kaye’s most intriguing pick (at number ten) was for Dadawah’s Peace & Love Wadadasow (with the title mistakenly given as Love and Peace), one of the most obscure of the many albums cited in the volume. So obscure was it that I, and I’m guessing many other teenage readers, were unable to hear it for decades, if they were able to hear it at all. I even wondered whether it might be a made-up record he slipped through as an inside joke, as if it was some imaginary lost classic by a hippie tribe for which collectors would fruitlessly scour want lists.

But it was a real 1974 reggae album, and one that’s not been widely reissued as far as I can tell. Nor was it even widely heard among reggae fanatics, in part because it wasn’t like much mid-‘70s reggae, owing more to the sounds of Jamaican Nyahbinghi music than most records in the style. Rooted in the sounds of traditional West African drumming, and some jazz and gospel, as well as the explosion of Jamaican reggae, Nyahbinghi was also strongly informed by Rastafarian spirituality. Count Ossie’s 1973 triple LP Grounation, itself not too easy to find for most of the years since its release, is the most esteemed record in the genre, and much easier to access since its 2022 reissue on Soul Jazz.

Dadawah’s album, featuring singer and longtime reggae icon Ras Michael, shares some of the same qualities, though it’s far more aligned with mid-‘70s reggae and dub sounds, and less with Nyahbinghi. It also has, unlike Grounation, state-of-the-art mid-‘70s Jamaican production with its crafty use of echo and space. Like some other rare records that are sought after because of one or two citations by legendary figures as all-time classics, Peace & Love Wadadasow isn’t as much of a knockout as its placement on a high-profile best-of list might lead many to expect. But it’s a very haunting endeavor, and not too typical of Jamaican reggae releases in featuring just four tracks, all of them lengthy, adding up to nearly forty minutes.

Its feel is as much, if not more, of an eerie chanted religious ritual as a popular music release, It’s heavy on minor-key melodies, booming bass, the odd keyboard tinkle (by Lloyd Charmers, who co-wrote much of the material with Ras Michael), spare guitar licks, and inventive African-influenced percussion. The lyrics aren’t so much phrases and sentences as incantational chants, soaked in Rastafari vibes. The production, as maybe the biggest enticement for many listeners, has a reverberant, slightly woozy glow that’s dub-informed but not all-out dub. The overall effect is much like hearing thoughts bouncing around the heads of a circle of Rastafari followers, vocals often call-responding and overlapping with each other in a semi-hypnotic state.

This CD reissue expands the record to two discs, the first of the pair featuring the original album. The bonus disc takes some liberties in its inflation of the running time, since just one of the 22 tracks, the 1974 instrumental “Burning Drums,” is by Dadawah. The unifying thread is the involvement of Lloyd Charmers on a host of 1973-76 recordings, occasionally as artist, and also as producer and arranger. All of these were B-side “versions,” as wholly or largely instrumental variations of more conventional tracks were often called, and include cuts credited to a couple big reggae names in Ken Boothe and Delroy Wilson.

These are reasonably interesting dub productions, but don’t have too strong a specific connection to the Dadawah album on the first disc, or nearly as strong a tie to the Nyahbinghi style. You can’t always tell by the song titles, but some of them are based on familiar American hits like the Stylistics’ “You Make Me Feel Brand New,” Clyde McPhatter’s “A Lover’s Question,” and the Everly Brothers’ “Devoted to You.” A bit of Santana-like guitar sneaks in for C.H.A.R.M.’s “After Midnight,” if you’re on the lookout for something a little different. (A shorter version of this review appeared inUgly Things.)

19. Various Artists, Having a Rave-Up! The British R&B Sounds of 1964 (Grapefruit). A three-CD, 91-track compilation with this theme could hardly have been more up my wheelhouse. This does cover almost all of the major and minor names working in this incredibly vibrant and influential scene in 1964, though it’s not a flawless overview, if such a thing could exist. It would rank higher on this list if I didn’t have almost all of the really good tracks, and if the obscurities were more on the level of such cuts.

Besides the Rolling Stones and Them—whose material couldn’t be licensed—this ticks off all of the big names: the Yardbirds, the Pretty Things, the Animals, Manfred Mann, John Mayall, Graham Bond, the Kinks, Georgie Fame, and the Spencer Davis Group. And all of the more cultish names: Downliners Sect, the Artwoods, the Birds, David John, the Fairies, and Duffy Power, for starters. And then the lower tiers that managed some good sides, some unreleased at the time: the Others, Bo Street Runners, the T-Bones, the Mike Cotton Sound, and the First Gear are just some. Some of the selections, as per the Grapefruit label’s modus operandi, are so obscure few other than compiler David Wells have probably heard them, which especially goes for the nine previously unreleased tracks.

You can’t argue with the cream of this crop—the Pretties’ “Rosalyn” and “Don’t Bring Me Down,” the Yardbirds’ “I Wish You Would” and “I Ain’t Got You,” the Manfreds’ “I’m Your Kingpin,” Downliners Sect’s “Sect Appeal,” the Artwoods’ “Sweet Mary,” Mayall’s “Crawling Up a Hill,” the Fairies’ “Anytime At All,” and the Birds’ “You’re on My Mind,” for instance. Refreshingly, there are R&B-inclined cuts by major acts who didn’t make those their main dish, like the Zombies’ “Woman,” Dave Berry’s snarling “Don’t Give Me No Lip Child,” and the Hollies’ “Memphis.”

There’s also the odd goodie by acts who never made another notable record, like the Plebs’ crunching reworking of the folk standard “Babe I’m Gonna Leave You” and Shel Naylor’s take on the Dave Davies-penned “One Fine Day,” which the Kinks didn’t put out in their own version. There are highlights by acts that really didn’t rise to them too often, like the Nashville Teens’ ominous, rumbling “T.N.T.” There’s Screaming Lord Sutch, not usually lumped in with this crowd, but deserving of membership with “Come Back Baby.” The Johnny Kidd-less Pirates do a terrific “Castin’ My Spell” with Mick Green on guitar. There’s even Rod Stewart, albeit on a slightly lo-fi live cut by the Hoochie Coochie Men; Steve Marriott, as part of his pre-Small Faces group the Moments; and the Who, albeit when they used the High Numbers billing for their uncharacteristic and rather unimpressive debut single, “I’m the Face.”

In all this makes a reasonable and representative starter comp for those just getting into ‘60s British R&B, though those who are probably already have a lot of the material. That doesn’t mean some of the selections by the better known artists couldn’t be questioned. Debates could fill up a few pages and yes, everyone has their particular favorites. But as one example, the Searchers’ “Ain’t That Just Like Me” rave-up certainly slays the relatively pedestrian cut heard here, “Gonna Send You Back to Georgia.”

There’s also a big gap between the quality of the rarities and the established, much-anthologized acts and tracks. There are too many covers of oft-done standards that not only don’t stand up to the US originals, but sometimes pale next to good UK versions of the same tunes. Most of the unreleased material is on the generic side, but the Tridents’ lengthy-for-the-time (five-and-a-half-minute) live workout on “Tiger in My Tank” is notable for featuring Jeff Beck on guitar, with the same kind of manically fleet riffs he’d use on Yardbirds songs like “Evil Hearted You.” It all makes for an uneven if oft-exhilarating ride, but Wells’s 48-page liner notes are as usual a big bonus, packed with info and vintage photos/graphics. (This review previously appeared in Ugly Things.)

20. Robbie Basho, Snow Beneath the Belly of a White Swan: The Lost Live Recordings (Tompkins Square). He might have been a fairly obscure cult figure, but you wouldn’t guess it from the relative deluge of Basho product in recent years. There was a documentary, a five-CD box of unreleased material (Songs of the Avatars: The Lost Master Tapes), and yet another CD of unreleased early ‘70s sessions (Songs of the Great Mystery). In 2024, we have this five-CD set of yet more previously unissued recordings. Basho did release a lot of albums in his lifetime, but there’s much more to hear now than ever.

Basho wasn’t so great at documenting what was done when and where, however. Almost half of this set—all of discs one and three, and two of the six tracks on disc five—are noted as “date and location unknown.” Dates and locations of a few others are given educated estimates. It’s at least known that all of disc two was taped at Cowell College in Santa Cruz on May 13, 1967; much of disc four at Stanford University on October 19, 1969,;a couple tracks on disc five in April 1976; and some other cuts likely in 1970 and 1972. As Basho lived until 1986, theoretically the box could span his whole career. The recording quality is variable, but overall pretty good, ranging from excellent to easily listenable.

Dates aren’t as important as the music, which is pretty good and very characteristic of what you’d expect from Basho in concert: largely instrumental acoustic avant-folk guitar, with lots of shadings from non-Western forms like Indian and Native American music. He occasionally sings, and while it’s become a cliché to describe his vocals as an acquired taste, certainly his shaky and spooky delivery will strike many as bizarre, even for some who admire his instrumental skill. The melodies are minor-flavored and darkly haunting, and while there are similarities to his contemporary John Fahey, Basho is less accessible, and more unremittingly melancholy in tune.

Which makes this set eminently suitable for gray rainy days, though it’s a lot to take in at once; doesn’t have enormous variety; and isn’t at the top of what might be considered his best and most important recordings. Disc two might be the best place to start, both because its certain date and location provide at least some historical context, and there seems to be somewhat more of an Indian flavor to the material and execution. Thorough liner notes do the best they can to give some of that context given the mysterious provenance of much of what’s here, though there could have been clearer citations of what songs appeared on which of his other albums, given his complicated discography. The booklet does reproduce some rare posters, one of which is included as a full standalone foldout.

21. Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young: Live at the Fillmore East, 1969 (Rhino). This September 20, 1969 concert was one of the earliest CSNY gave. Only a month after their second one at Woodstock, it predates the release of their first album with Young (Déja Vu) by about half a year, and the recording of their live 4 Way Street album by eight to nine months. Divided into an acoustic set and an electric set, with top-notch fidelity, it carries quite a bit of historical weight.

Besides including versions of most of the songs on 1969’s Crosby, Stills and Nash LP—acoustic ones of “Helplessly Hoping,” “Guinnevere,” Lady of the Island,” “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes” “You Don’t Have to Cry”—there are previews of Dêja Vu’s “Our House” and “4+20,” as well as the 1970 non-LP B-side “Find the Cost of Freedom.” There’s more: a cover of the Beatles’ “Blackbird,” Neil Young’s Buffalo Springfield song “On the Way Home,” Young’s “Sea of Madness” (a different version than the one on the Woodstock soundtrack) and “Down By the River,” and a Young song, “I’ve Loved Her So Long,” from his self-titled debut album. Stills’s “Go Back Home,” which he performs as a solo acoustic piece, wouldn’t find official release until his 1970 self-titled debut album; “Bluebird Revisited” (done electrically), an entirely different song than Buffalo Springfield’s “Bluebird,” wouldn’t see official release until Stills’s second album.

4 Way Street, a huge hit record, was nonetheless sometimes criticized for performances that weren’t always as tight as expected. That’s not a problem on this considerably earlier set for the most part, though the harmonies fall apart at one point in “Helplessly Hoping.” But for all its imperfections, 4 Way Street has more energy and spontaneity, in the acoustic as well as the electric tracks. The material here, particularly on the acoustic half, is a little more sedate and tentative. If 4 Way Street is sometimes regarded as a bit peripheral to the main body of work CSNY produced in 1969 and 1970, this is yet more of a supplemental recording, though one worth hearing for dedicated fans.

22. Colosseum, Elegy: The Recordings 1968-1971 (Esoteric). Colosseum were a pretty popular recording act in their native Britain, with three of their albums making the UK Top Twenty. But not many would have anticipated such a flood of Colosseum product in recent years. There was a six-CD set of 1969-71 BBC recordings; five separate albums (one a double CD) of live concerts from the same era; and, around the same time as the set detailed in this review, a double CD (Upon Tomorrow) of yet more 1969-70 live recordings, along with studio outtakes of material being worked up for a possible album that could have been released in 1971. We also have this six-CD box set, Elegy, which has all five of their LPs from this period (one live and another that was US/Canada-only). Bonus tracks are added to a few of them, and there’s a sixth disc of “additional live recordings” from 1971. It’s the time of colossal Colosseum.

It’s also a lot to take in at once, even if you limit yourself to this mini-sized box, each CD except the sixth housed in sleeves replicating the original artwork. Colosseum specialized in brawny jazz-blues-rock that got more hard-rocking and blustery as time went on, especially when they changed vocalists. Featuring veterans of John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, a couple of whom had also done time in the Graham Bond Organisation, they’re best heard on their 1969 debut Those Who Are About to Die Salute You.

This is when their blend—quite an innovative one in the late 1960s—was at its most accessible, especially on a remake of one of Bond’s best songs, “Walking in the Park.” While there’s some meandering, there are also some solid blues-rock riffs, set apart from the usual such British fare by Dick Heckstall-Smith’s saxophone and Jon Hiseman’s pummeling drums. Three November 1968 bonus tracks on disc one include a demo of “Those About to Die” and two outtakes, Quincy Jones’s “In the Heat of the Night” and guitarist/singer James Litherland’s “I Can’t Live Without You,” indicating Colosseum had some ambitions to get just a bit poppier, though they could never quite effectively cross that line.

They got a bit proggier on their second effort, Valentyne Suite, with a three-part suite and generally more extended and ambitious arrangements. The material’s not as focused as the debut’s, though still with its share of just-about-catchy riffs and virtuosic interplay that doesn’t quite lose sight of a nominal if loose blues-rock base. The disc two bonus track “Tell Me Now” again indicates they made some tentative efforts at greater accessibility, without ever seeming like their hearts lay strongly in that direction.

To the perpetual confusion of collectors and discographers, 1970’s North American release The Grass Is Greener used some of the same tracks from Valentyne Suite, but with guitar and vocal overdubs by new member Clem Clempson, adding a few songs that hadn’t been on either of their first pair of UK albums. It’s pretty hard to keep what’s what straight even after reading liner notes several times, but the basic effect is about the same as Valentyne Suite, even if it’s not exactly a different version of that LP. As befits an act with ties to Mayall and Bond, one of the better tracks covers Jack Bruce’s “Rope Ladder to the Moon.”

From later in 1970, Daughter of Time marked a decisive change of direction for the still-young band, and not for the better. Most notably, Chris Farlowe came in as lead vocalist for the majority of material, including a cover of another Bruce staple, “Theme from an Imaginary Western.” Vocals had never been Colosseum’s strong suit, but replacing adequate yet serviceable singing with a better known figure with a far less suitable, overly dramatic style did not add up to a plus. The band as a whole were drifting toward a more pompous, freewheeling, and sometimes indulgent stance. Three bonus tracks on disc four include a demo of “Bring Out Your Dead” and a version of The Grass Is Greener’s “Jumping Off the Sun” with Farlowe on vocals.

Recorded in March 1971, Live largely offers reworkings of tracks from studio albums, including “Rope Ladder to the Moon” and “Walking in the Park,” with a few other items, including “Stormy Monday Blues,” with Farlowe as the chief singer. He also takes that role on the “Additional Live Recordings” disc, which has different versions of some tunes also on Live, but adds a few others, most notably “The Machine Demands a Sacrifice” and “The Valentyne Suite.” While the final disc is largely on the same level as Live, Colosseum in concert during this era could vary between the exciting and the challenging to endure, including when the admittedly terrifically talented Hiseman went into too-long drum soloing. The booklet’s lengthy liners go into detail on all of the recordings, which as noted are hardly the whole story of Colosseum on tape during this era, other releases including more than double the large amount of music on this package. (This review previously appeared in Ugly Things.)

23. Colosseum, Upon Tomorrow (Repertoire). As part of a deluge of recent archival Colosseum releases, one of the more modest is this two-CD compilation. The first disc presents the audio of a couple filmed performances in 1969 and 1970; the other has tracks that might have formed a foundation for a fourth UK studio album, though Colosseum broke up in late 1971 before such an LP could be issued. They’re not as essential as their best recordings, but have their interest for Colosseum completists, of which there must be a number considering how much product by the band from this era is available—about twenty CDs’ worth, in fact.

The first two tracks on disc one were taped, in decent sound, in March 1969 at the filming of Supershow, a production also featuring performances by Led Zeppelin and the Modern Jazz Quartet. Colosseum offer lively takes on a couple instrumentals from their debut album, “Debut” and “Those Who Are About to Die Salute You,” at a time when their fiery mixture of jazz, rock, and blues (and, on “Debut,” a bit of funk) was fresh both within the band and to the public.

These are followed by a couple longer live May 1970 pieces filmed for television, also in decent fidelity. “Downhill and Shadows,” which lasts a good twelve minutes, wouldn’t appear on their records until late 1970’s Daughters of Time, and reflects their move toward a more extended progressive rock, with a five-minute drum solo from Jon Hiseman. So does the nine-minute “The Valentyne Suite,” which had served as the finale to their second album in 1969. “Downhill and Shadows” does afford a chance to hear the number with guitarist Clem Clempson on vocals, rather than Chris Farlowe, who’d take over most of Colosseum’s singing by the time it was included on Daughters of Time.

Disc two is wholly devoted to demos and archive recordings that might have comprised and/or been reworked for a fourth UK album. (Note Colosseum already had four studio albums if you include 1970’s North American-only The Grass Is Greener, which had some previously released songs, but included some tracks unique to that LP.) Three cuts are demos from August 1971; another was done at a different studio later that month; and four aren’t dated, though presumably they’re from a similar era.

Whether or not it’s a facsimile of a finished or nearly finished fourth album, this second disc is a peculiar assortment of pieces, certainly relative to Colosseum’s previous output. As audacious as their concept was, that material often had just-about-hummable riffs. Much of what was being worked on shortly before their split saw them venturing into yet longer, oft-winding excursions in line with the day’s most ambitious and at times impenetrable art rock.

Never was this more apparent than in the twelve-minute “The Pirate’s Dream,” heard in two versions. Like quite a bit of what they were working on, it have been hell for the musicians to memorize given its diffuse structure, and almost as difficult for audiences to follow. Sometimes the abandoned album doesn’t sound a million miles away from the likes of Kingdom Come, but without as appropriately eccentric a vocalist as Arthur Brown.

It’s questionable as to whether Colosseum could have maintained their fairly extensive British and European audience with such material. The first disc—when their jazzy elements, particularly Dick Heckstall-Smith’s saxophone and Hiseman’s explosive drumming, set them apart from most blues-rock acts—more effectively showcases their best assets, and the ones for which they’ll be principally remembered. (This review previously appeared in Ugly Things.)

24. Jorma Kaukonen, Reno Road (Fur Peace Productions). In summer 1960, then-college student Kaukonen recorded the material on this Record Store Day double LP, taped by his friend Jack Casady. While as easygoing blues-folk it’s decent but not special, it’s historically remarkable for a couple reasons. Even at this early stage, Kaukonen was a superb guitarist, and while his vocals are just adequate (and would, more so than his guitar work, get better), on the whole he doesn’t sound too much different than he did playing solo or in Hot Tuna ten or more years later. Also, his repertoire was already similar to early Hot Tuna’s. In fact, more than half dozen of the 23 songs here were either on Hot Tuna’s debut or on recordings from the gigs in late 1969 taped in consideration for that LP, some of which have come out on archival releases. It’s a little like hearing a Hot Tuna album without Casady. Had he not joined Jefferson Airplane, maybe this is how Kaukonen would be remembered—an above average white blues interpreter whose guitar was way above-average. Of course he went on to be much more than that, but this is where he started. The package reproduces the tape box and has a few photos of Kaukonen and Casady from the time, along with a brief liner note from Jorma.

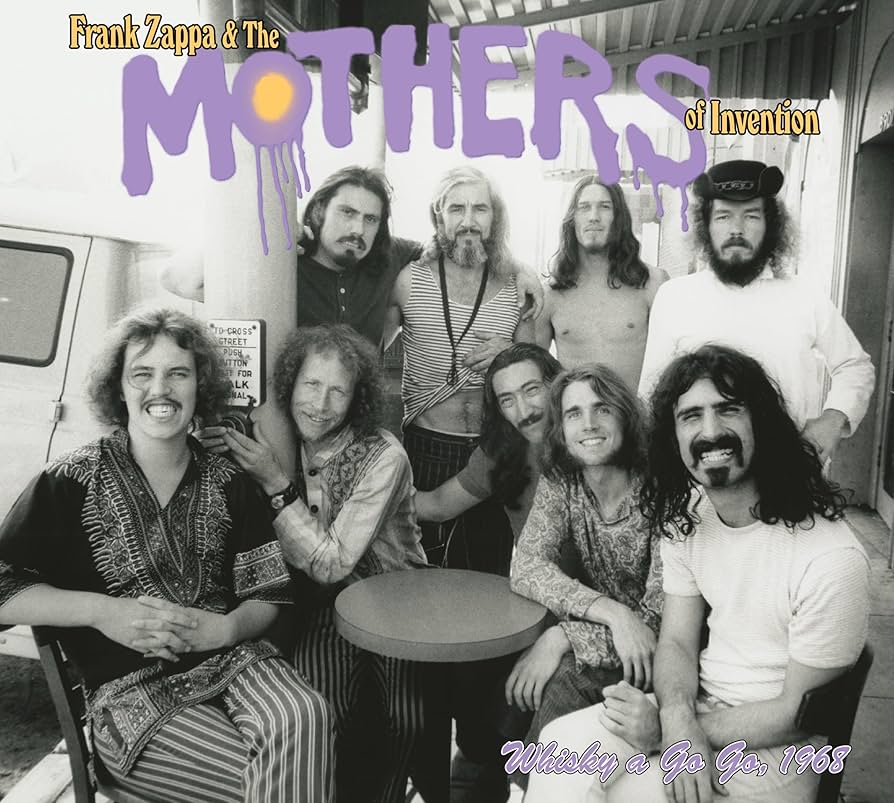

25. The Mothers of Invention, Whisky A Go Go 1968 (Zappa/Universal). It’s a small matter, but although this is billed as a release by Frank Zappa & the Mothers of Invention, I’m crediting it just to the Mothers of Invention, as that’s how they were billed at the time. This three-CD set presents previously unreleased material, recorded live at the Whisky in L.A. on July 23, 1968, taped with the intention of gathering cuts for official release. Although the sound’s decent, it’s not great, and it’s not surprising it wasn’t issued at the time.

Sometimes I note that a selection on my lists makes it more for historical interest than for the excitement of the actual music itself. This fits that category more than any other record I’ve put on my year-end blog lists. As big a fan as I am of Freak Out and We’re Only In It for the Money, and to a significantly lesser degree of most of their other late-‘60s records, I’m astounded by how much less I enjoy the relatively few live recordings of the 1960s Mothers than their studio work. It’s almost as though they tried to be defiantly inaccessible in concert, seldom playing their most hummable, yet very complex and witty, tracks from those great Freak Out and We’re Only In It for the Money LPs. This isn’t unique to this Whisky set; I feel similarly about some other archive releases, like the one featuring 1967 live recordings in Sweden.

There’s a bit of attention given to the most accessible songs from their early releases here, particularly “Hungry Freaks Daddy,” as well as the more overtly comic “Status Back Baby” and “Brown Shoes Don’t Make It.” Much of the playing, though, is jazzy or avant-garde improvisation, with jokey versions of a couple oldies (“My Boyfriend’s Back” and “Memories of El Monte”) along the way. I know theatrical visuals were big parts of the appeal of early Mothers performances, but that’s lost on an audio-only document. Not everyone agrees, but I also find much of the humor strained, which isn’t something I’d say of the still-clever satire on the early studio albums. It’s almost as though they’re holding back biting but catchy songs like “I’m Not Satisfied” and “I Ain’t Got No Heart,” not to mention disregarding the still-recent We’re Only In It for the Money, though live versions of the likes of “Who Needs the Peace Corps” and “Flower Punk” would be most welcome.

It’s frustrating, at least for my tastes, since “Hungry Freaks Daddy,” done with a different and jazzier lineup than the one that played it on Freak Out, proves they could do such early material in good arrangements that didn’t duplicate the studio ones. The experimental passages aren’t without their merit, even if I find them more interesting than engaging. Which means this record, while a document of note, isn’t something I’ll be playing much.

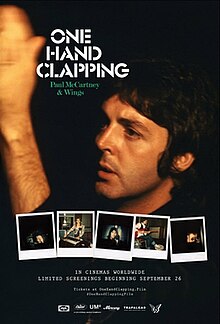

26. Paul McCartney & Wings, One Hand Clapping (Capitol). In late August 1974, McCartney and Wings were filmed playing in Abbey Road studios for a planned documentary. (Additional recording was done in October, with brass overdubs in January 1975.) The film didn’t come out, though some of the songs taped have shown up on archival CDs, as has footage. The documentary was only a little more than an hour long and included some non-music material, so this double CD, with about 83 minutes of music, has some stuff that wouldn’t have been heard in the film. (For what it’s worth, the film was also broadcast on UK TV in 2024, which I was unable to see.) There aren’t many records where I feel so much distance between the energy and quality of the leader’s performance (especially his vocals) and the quality of the actual songs. This coming from one of millions of self-anointed world’s biggest Beatle fans – as much as I love Paul’s work in the Beatles, I’m not a big fan of his solo efforts, even the early ones, though most of what’s here is okay.

Still, this does have many of his best and most popular early solo songs, sometimes done with orchestration, and with decent band backup, even if they can’t match the skills of the leader. Those tracks include “Jet,” “Maybe I’m Amazed,” “C Moon,” “My Love,” “Band on the Run,” “Live and Let Die,” “1985,” “Let Me Roll It,” “Junior’s Farm,” “Sally G,” and “Hi, Hi Hi.” They also include some forgettable early Wings filler and Denny Laine singing on the Moody Blues hit “Go Now,” and, and no one needed McCartney’s take on “Baby Face.” At this point he was reluctant to revisit his Beatles past, and the versions of “Let It Be,” “The Long and Winding Road,” and “Lady Madonna” are brief and noncommittal. Even discounting the absence of Beatles songs, certainly some of his better early-‘70s tunes are missing, particularly “Uncle Albert” and “Helen Wheels.” Hardcore McCartney fans might also lament the absence of relative obscurities like “Give Ireland Back to the Irish” and “The Mess.” But most of this is a well-chosen overview of his early solo repertoire and Wings as they reached their relative peak.