Richard Morton Jack’s new book Pressing News: British Music As It Happened 1962-1972, as detailed in my previous post, is built around reproductions of more than a hundred press releases for British rock artists between the early 1960s and early 1970s. Usually the releases are tied to specific records, from the most famous (Sgt. Pepper) to some by very obscure acts (Fresh Maggots, Jerusalem, and the Pete Best Four, to name just a few examples). These are accompanied by quite a few reprints of reviews, and sometimes full stories, that appeared about these records and acts at the time, not years later, when critical views about the performers and their importance often shifted. There are also reproductions of some ads from the period, and each entry has a substantial paragraph from the author explaining the context of the material and the performers’ career at the time.

I described a few of the entries in my previous post. This month I took the opportunity to ask the author about how the book was assembled, and what the press releases can tell us about British rock of the period. The book can be ordered through https://lansdownebooks.com.

I think they’re interesting and worthwhile and deserve to be proliferated. Having collected a large number, it seemed obvious to me to share them in book form. Not all of them contain revelations, but a lot of hard information about often obscure artists or much-loved classics can be gleaned from them, and – if you read between the lines – they contain fascinating insights into the way music was marketed in that period. They’re period pieces, for sure, and often use language that is quaint or even absurd to modern sensibilities, but I think that makes them of sociological as well as musical interest.

Music press releases aren’t the easiest things to collect, since I would guess almost all of them are quickly discarded after they’re received. A few journalists and the like saved some, and some collectors have been lucky enough to find them in the original LPs. But how did you go about accumulating such a large collection of them, and what were the biggest challenges in doing so?

You’re right – by definition, press releases are scarcer than the records they relate to, and most were instantly tossed. In fact, I’m unaware of any record company that maintained an archive of them. I discussed this with Chris Blackwell, and he expressed regret at Island’s cavalier (in hindsight) attitude towards its marketing materials, which were frequently gathered and thrown away. I acquired mine piecemeal, often on eBay, but also through generous-spirited fellow collectors who know I value them. I also had the good fortune to acquire a large number from the estate of the music journalist historian Fred Dellar. The biggest challenge in collecting press releases, and all promo materials, is the fact that no one knows what existed in the first place until it happens to pop up. There are no catalogues or lists, or specialist dealers in such things. It makes it a fun but frustrating area.

What were the biggest surprises you found in the press releases, both in terms of their general approach during this decade, and specific examples of things you didn’t know or that you found surprising were being promoted?

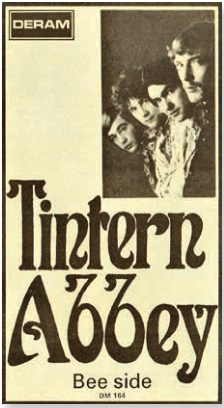

It’s constantly striking that in many cases the people writing them had no idea how the record in question was going to fare – there’s a freshness to reading about artists that are now regarded as ‘legendary’ when they were just embarking on their careers. I mean, when Decca released Tintern Abbey’s sole 45 in November 1967, they didn’t have a clue whether it would be another “Whiter Shade Of Pale,” which had shot to number one from nowhere that May. The major labels followed the same formula in many of their press releases, with a short descriptive page followed by a questionnaire. Some of the questions and answers are ludicrous in one sense – who needs to know that Ringo Starr disliked Donald Duck? – yet it’s important to remember that these press releases were serving a wide range of publications, many of which catered for children, so they had to cover different bases. It’s also intriguing to see how many major stars were already hard at work well before they found success: Joe Cocker, Rod Stewart, David Bowie, Jimmy Page, Robert Plant and so on. In their cases clearly it was just a matter of time.

Although press releases are the core of the book, a lot of space is also given to reprints of articles about the acts spotlighted in them, as well as vintage advertisements and reviews. You’ve used excerpts of many reviews in your huge and comprehensive reference guides to UK and North American records of the 1960s and early 1970s, but these reprint the reviews in their entirety. What’s the value of reading these vintage reviews?

Record reviews were typically written by people who had – I assume – only just glanced over the relevant press releases, so marrying up the two seemed logical. I wanted to demonstrate how the press releases might have influenced what was written – or not. It’s important to remember that record reviews were almost always written at great speed, without serious engagement with what the artist was trying to convey. One prominent music journalist of that period told me that, on the publication he worked for, LPs with voluminous notes on the back cover were the most sought-after for review, because you didn’t have to listen to the music in order to bash out some copy. So, in short, I wouldn’t say that all old reviews necessarily contain worthwhile insights, but if interpreted in the right spirit they offer another fascinating window into the way pop was marketed and promoted. As the book’s subtitle indicates, I wanted to put the reader in the moment as far as possible. Towards the end of the decade, of course, reviewing albums became a more serious affair, and certain critics, such as Mark Williams of International Times, wrote with considerable intelligence and insight.

Records now esteemed as classics were sometimes dismissed or ignored when they came out, and some very popular ones are now disdained or seldom discussed. What are some of the most striking examples of how differently a record/act is perceived now than then?

I agree, many of the most popular groups of the 1960s are barely listened to today. I wonder how many people can identify more than a handful of songs by Herman’s Hermits, the Dave Clark Five, the Love Affair and so on, yet the music press was jammed with coverage of them in those days. Conversely, artists that barely made a ripple in those days are now widely admired, even if their audience remains small: COB, Fuchsia, Nick Drake and so on. Time Of The Last Persecution by Bill Fay, a deeply personal and heartfelt record set to adventurous rock arrangements, was scorned by critics upon release, yet resonates powerfully with many people down the decades. Conversely, an awful (to my ears) album called Ark II by Flaming Youth was garlanded with praise upon release and has no critical standing today, and the well-known journalist Charles Shaar Murray championed a dreadful (to my ears) group called Gnidrolog. Inevitably, tastes change over time and cream can be slow to rise.

Sometimes received wisdom about an act – not just their musical quality, but basic facts about their career – are called into question or disproved by artifacts like press releases and reviews. As Nick Drake’s biographer, you found this when you uncovered numerous complimentary reviews demonstrating he wasn’t ignored or dismissed in his lifetime, as some other historians have conveniently claimed. The same holds true for the Velvet Underground, and there are other instances. Is this something you often discover, and are there a few particularly interesting examples you’d like to cite, whether Drake or others?

I am constantly uncovering intriguing information from vintage sources that disprove received wisdom. We’re talking about an era in which there were numerous weekly newspapers devoted to current popular music, as well as various monthly magazines, yet depressingly few writers and researchers use them. It always surprises me how many famous albums’ release dates are constantly cited inaccurately. Only yesterday I was ridiculed online by [a writer] for pointing out that he had the release date of Neil Young’s debut album wrong by three months. Upon request, the sources he cited were its Wikipedia and Allmusic pages. So I hope the book will help to correct a few dating errors, at least.

Some artists who are typically portrayed as unfathomably overlooked did, in fact, receive a good deal of coverage. Vashti Bunyan springs to mind – her album was widely and warmly reviewed at its time of release, and she received feature coverage in both the music and the national press (not that it influenced the record-buying public!). As anyone who has ever worked in the record business will tell you, trying to break a record by an artist with no live / public visibility is a fool’s errand, and that often explains why such acts failed to connect, rather than their going unmentioned in the press.

On a related note, very few albums received absolutely no coverage at all. One example – as far as I am aware – is Beginnings by Ambrose Slade, which came out on Philips’s Fontana imprint in May 1969. Of course, what’s especially interesting about that is that they went on to [as Slade] become one of the biggest British groups of the 1970s.

As one of the leading collectors of the UK music press at the time, you know how important it is to preserve and research issues of the weeklies and monthlies that had vital information. Even some of the weeklies with big circulations, like Record Mirror and Disc, often aren’t easy to find, even in libraries with big collections of vintage papers. The value of their reviews/interviews/stories is obvious, but of the four most popular ones (NME, Melody Maker, Record Mirror, and Disc), do you find notable differences in their quality and approach, having read more of them than virtually anyone?

In the period covered by Pressing News, the simple answer is that Melody Maker wasn’t predominantly chart-focused. The others, whilst covering of a wide variety of artists, were fundamentally geared towards those who were having hits. (This shifted in the 1970s, to some extent.) As such, Melody Maker tends to contain the most detailed, thorough and wide-ranging coverage, but all of them are valid and contain interesting and thoughtful journalism – as do Combo, Music Echo, Top Pops, Music Now, Record Retailer, Music Business Weekly and so on.

A significant attribute of Pressing News’s sections for reviews and stories is that you also reprint material from much more obscure music publications that are very hard to find vintage issues of now. There’s Beat Instrumental, which paid more serious attention to musicianship than other publications, and ZigZag, which was the first widely distributed underground-oriented UK music magazine of note. But there are also ones that are yet far more obscure, like Music Now and Top Pops, as well as some business-oriented publications that few have paid attention to. What are the biggest challenges in finding those back issues, and what are some particular values some of the more obscure papers provide?

The biggest challenge in collecting the more obscure music publications is obvious: far fewer copies were printed and sold, so far fewer survive. It is virtually impossible to assemble complete runs of some of them, and the British Library’s collection is far from complete. There are gaps in my collection that I may never fill, and in one or two cases I wonder if the missing issues even exist anywhere. Certainly no person or institution I’m aware of has them. In terms of their content, as a rule of thumb, the more obscure a paper is, the less likelihood it had of bagging interviews with major stars, so papers such as Music Now often feature acts that received scant attention elsewhere. The same applies to photographs and adverts.

Pressing News also spotlights music coverage from general interest papers, rather than music or even entertainment ones. There are stories from the newspapers of cities around the UK, some of them sizable cities, some of them quite modest in circulation. For instance, there’s even a review of the Beatles’ first single, “Love Me Do,” in the Newtown & Earlestown Guardian. You’ve unearthed many such items, which is a source of great satisfaction to researchers unaware of such material. Yet there must also be frustration knowing there must be many more such items in publications that are difficult to find in any form, and extremely time consuming to peruse for the rock-oriented coverage that happened to pop up. What are the biggest rewards and challenges of trying to find such material?

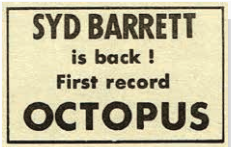

The joy of looking through such papers is not knowing what may lurk over the page. It’s time-consuming, but always a thrill to discover an unfamiliar review or article relating to an artist I consider worthwhile. In recent weeks I have found pieces that include a photograph of Syd Barrett performing a solo show in 1970, and of Jimmy Page performing with a group under a pseudonym in late 1963, neither of which have ever been circulated, to the best of my knowledge. In writing my Nick Drake book, I attempted to pin down every piece of press that he received during his lifetime, but I am aware that there must be more. Received wisdom had it that he only ever gave one interview, but I came across another, and am wide open to the possibility that others might exist.

Records were sent out widely for review, and I have been told that local newspapers often wielded more influence over young record buyers than the music press, hence their pop writers were carefully cultivated by record companies. However, their writing was often lazy. I was delighted to find a long piece about Egg from the summer of 1969, then realized it was a word-for-word reprint of Decca’s press release for their debut 45. They’re not the only act I had to omit for a lack of supporting material in the music or general press. Bulldog Breed come to mind, too, and there are a few others.

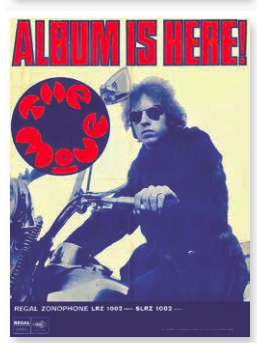

It’s odd that a Move album was reported to be on the way in late 1966, yet didn’t appear until early 1968. Odder to me is a report on April 24, 1967 that their manager announced tapes had been stolen from their agent’s car in Denmark Street, a factor in delaying an album release for quite some time. Do you think this might have been planted?

In short, the answer is yes – their manager, Tony Secunda, was a great believer in publicity at any cost (and the cost ended up being pretty high when the Prime Minister sued them), so he fed a steady diet of bullshit to anyone willing to consume it. I’m sure they’d have been successful without his gimmicks, but either way, the saga of the Move’s first album / early recording career is long and vexed, and it’s a shame they didn’t have an album out in late 1966.

For the Who’s My Generation album, there are a couple press reprints of great value, from papers that aren’t easy to access. In the July 1965 Beat Instrumental, there’s an advance report of sorts on what was initially supposed to be the Who’s first LP, describing eight tracks (although the story refers to an acetate with nine, only eight are detailed). All but one of the songs were covers, and they, quite unusually considering there must have been pressure to get an album out quickly to capitalize on their first two hit singles, decided to pretty much start the album over, only keeping four of the eight tracks for the final My Generation LP. Then in the December 4, 1965 Record Mirror, Pete Townshend gave a detailed track-by-track rundown of the album, and a very forthright one, heavily criticizing some songs and insinuating some criticism of Roger Daltrey and producer Shel Talmy. I’m devoting a full future blogpost to these items, but would you agree it was both very unusual to have such an advance report of an album in the making in 1965, and very unusual to have such a track-by-track rundown from the main songwriter/leader, though such rundowns would become more common in future years?

Yes, I would agree. From the start Townshend was unusually outspoken and forthright, both to the press and as regards what he wanted the group’s recordings to consist of. It’s intriguing that the scrapped first version of My Generation got so far as to be reported in detail. Asking artists to comment on each track on an album wasn’t unheard of, though – off the top of my head, I can recall the Beatles, Scott Walker, Roy Wood and others doing so too. But to insult your own work in such plain terms is clearly peculiar, and typical of Townsend’s self-critical candour.

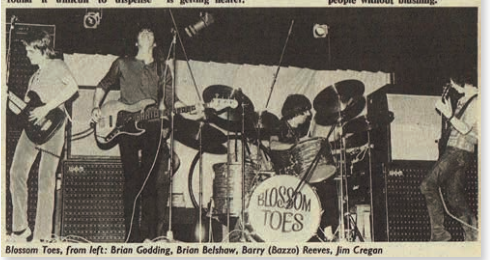

Getting back to press releases, one of the relative surprises of Pressing News is that many obscure acts who sold very few records were granted substantial press releases: Vashti Bunyan, Jackson C. Frank, the Virgin Sleep, Blossom Toes, Cressida, the Human Beast, Fresh Maggots, and Mellow Candle, among many others. Was it just considered pro forma by labels and publicists to churn out press releases regardless of commercial prospects, or sometimes indicative that they were considered to have had greater prospects than many realized? Or kind of a combination of those approaches?

Review copies of virtually every new record were accompanied by some form of publicity material, not least because record companies had precious little idea what would or would not connect and had to cover each base. Black Sabbath were treated with near contempt by Philips in the run-up to their first album’s release. (Almost unbelievably, none of the members had heard the finished LP or seen the cover before it was in the shops. Luckily, they were delighted with both.) Review copies of that album simply came with the usual bland Vertigo single typed sheet, yet it became a huge success right away. So I don’t think any record’s success can be attributed to whatever the publicity department said or did, though in some cases they made journalists’ lives easier by including obvious material to parrot. The Beatles’ “Love Me Do” press release even included a readymade review by Tony Barrow for reprinting! As time went on, more elaborate promotional materials started to be generated, often indicating a level of excitement about an act. For example, the first Yes album was promoted with a bespoke promo folder containing info on headed paper, photos and a poster. That said, such things were often funded by management or other interested parties, rather than the record company.

As many press releases as there are in Pressing News, obviously many more exist that could have been considered, particularly for big acts like the Beatles and Rolling Stones (for whom not every album is represented), but also for more obscure acts who aren’t represented at all. Were there criteria you applied in how you had to be selective, and any you regretted omitting?

One criterion was my own taste, hence the absence of disposable pop, mainstream ballad singers, novelty acts and so on. Another limitation was my memory: I recently found the press release for Reality by Second Hand inside the cover of my copy when I played it. I would have included it in the book if I’d remembered I had it. The same goes for But That Is Meby Mandy More. Another is the fact that I simply don’t have certain press releases – for example, I have the ones for Nick Drake’s Five Leaves Left and Pink Moon, but have never seen one for Bryter Layter. It seems unlikely that Island didn’t generate one, so I’ll just have to wait until a copy surfaces. The same goes for The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn and various others. Finally, I didn’t want to include too many by one artist, so I had to be selective about what to include relating to, say, the Beatles, the Stones and David Bowie.

Would you consider publishing another volume or volumes?

Yes, albeit with a certain hesitancy, because it was a fiendish book to lay out. Pressing News only covers Britain, and I have many American press releases that I would like to put into book form one day. Off the top my head, it would include rare and unseen material relating to Love, Captain Beefheart, Silver Apples, Big Star, the Monks, Fifty Foot Hose, Karen Dalton, Jefferson Airplane, Leonard Cohen, the Stooges and many others. To a lesser extent, I have press releases relating to artists from non-English speaking countries (Can, Culpeper’s Orchard, Pan, Oriental Sunshine etc), but those would obviously be more problematic to make into a book with any semblance of commercial viability!

Do you find notable differences between how US and UK acts were promoted, in press releases specifically, but also in how they gained press coverage?

American press releases weren’t much different to British ones – a mixture of hyperbole, quaint idioms and information of varying degrees of usefulness. The big difference between the territories is that, despite being a much larger market, America had a bafflingly limited music press compared to Britain (trade magazines aside). There were a few great publications – Hit Parader springs to mind – but no weekly music press until Go started publication in April 1966 (but that was a flimsy publication distributed via radio stations). Most pop coverage was in magazines aimed at youngsters, such as Flip and Sixteen, which – whilst occasionally pretty cool – tended to be flippant and superficial. A few regional papers appeared circa 1966, like New England Teen Scene and Mojo Navigator, and magazines like TeenSet, Hullabalooand Crawdaddy! took up some slack, but it wasn’t really until the end of the 60s that America had a really solid national music press, with Rolling Stone, Fusion, Circus, Changes, Rock and others appearing regularly. There were useful articles about interesting musicians in the national press, but these were often syndicated and consisted of rehashed press releases rather than original material. So, in general, serious American pop fans weren’t as well served by the press as British ones. As a sidenote, of course the American record industry was so enormous that no weekly consumer publication could have compassed it all.

Pressing News hasn’t been out for long, but has it resulted in any readers contacting you with copies of press releases you haven’t seen, and if so, have any been of special interest?

Alas, not! But press releases are very rare, and I didn’t publish the book in the expectation that it would result in a flurry of them resurfacing. But there are many wonderful records whose press releases I have yet to see, and I would be delighted if anyone were to share items of interest… For me, locating such things is all about sharing, not hoarding.

Pressing News can be ordered through https://lansdownebooks.com.