On this Mother’s Day, and with Father’s Day coming up next month, it’s now been more than five years since both of my parents passed away. As more time passes, I think about ways in which I’m similar to and different than my mother and father. As much of my professional life has been devoted to writing about music, I naturally think about our similarities and differences in that area.

More so than most of my family, the life I’ve led has been different than that of my parents, who were much more conservative in lifestyle, though politically fairly liberal. This extended to my musical and artistic tastes. Born in the mid-1920s, they were of a generation way past their teens when rock exploded in the mid-1950s. Even before that, my impression is that they were not big fans of the pop music of their youth, which was dominated by big bands and crooners. Their record collection, probably running somewhere between one and two hundred albums, was dominated by show tunes and classical music, genres for which I’ve never had enthusiasm.

On the other side, they had no interest in rock music, the form that dominated the popular entertainment of their children’s generation. To their credit, however—unlike many such parents—they made no effort to stop me from listening to it. From the age of five, I had a radio (AM only until 1972) in my room that I could listen to pretty much whenever I wanted. As a consequence, I’m familiar with almost all of the big AM radio hits from the end of 1967 through the 1970s from first-hand experience, not just from oldies radio or records. The first one that stuck in my mind was the Beatles’ “Hello Goodbye,” which makes sense as the radio arrived in my room around the 1967 holiday season, only a month or so before I turned six. I knew the song very well before I even knew it was by the Beatles.

More remarkably, I was allowed to stay up until 9:30 as a first-grader, and increasingly later with passing years. In part that’s because until I was eleven, I shared a room with a brother four years older. But when my first-grade teacher went around the class asking what students’ bedtimes were, that still sparked a puzzled, perhaps even worried expression on her face, given that virtually everyone else had a bedtime 60-90 minutes earlier. Many adults in the late 1960s (and even now) would view this as excessively permissive. In hindsight, my guess is that by the time I—the last of four sons in nine years—arrived, my parents were too busy supporting and raising the family to even think much about setting and enforcing bedtimes.

Around the time I entered high school, with my own record collection and interest in music of the past rapidly expanding, I became more curious about whether there’d be anything of interest in my parents’ collection. By this point they rarely played records, though they had more space to do so now that I was the only child left at home. But time was not bringing our interests closer together. There were exactly two LPs that piqued even mild curiosity on my part.

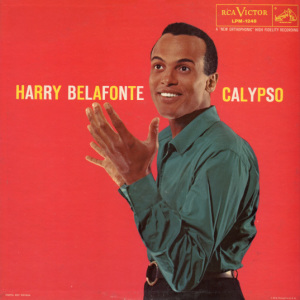

One was this #1 album by Harry Belafonte from 1956:

It’s a testament to how huge that record was that my parents, who did not seem to be even slightly aware of pop trends, had this in the household. It was #1 for 31 straight weeks. My point of entry into the album, such as it was, was its opening track, the #5 hit “Day-O (The Banana Boat Song).” It was, every so slightly, influenced by—or at least an influence on—early rock’n’roll. It was a few years before I learned that Bob Dylan made his first appearance on a record as a guest harmonica player on a Belafonte LP (the title track of the 1962 album Midnight Special). It wasn’t until quite a few years after that that I grasped the full impact of Belafonte upon the pop and folk scene, even if his contribution to the folk revival was on its poppiest side.

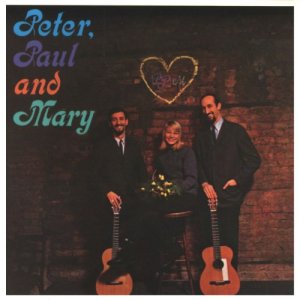

The other was the first album by an act that was at the very center of the folk revival:

There were some other albums by Peter, Paul & Mary in their collection, but this (with the hit “If I Had a Hammer,” though not with their biggest early-‘60s hit, “Blowin’ in the Wind”) was the strongest. To my recollection, there were no other records by folk revival artists among their LPs. As with Belafonte, this is a testament to just how huge Peter, Paul & Mary were—they sold albums to people who weren’t even folk or pop fans. I don’t have the empirical evidence to back this up, but judging from how popular and well known they also were among my parents’ friends, my guess is that Peter, Paul & Mary probably sold more per capita among suburban middle-class Jews than any other artist.

Although they rarely discussed popular music with me, my guess is that my mother was by far the more driving force behind listening to any sort of roots-tinged pop than my father. She still had some records—from back when “albums” were actual 78s grouped in photo album-like packaging—by Paul Robeson, though these were too fragile and harmful to styluses on modern equipment to play often, or at all.

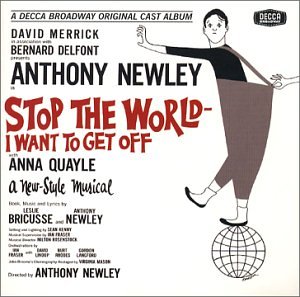

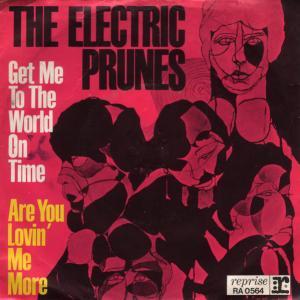

In contrast, in one of his few memories of listening to music as a boy, my father admitted that when his friends raved about big band stars like Tommy Dorsey, he’d say something like, “yeah, that’s alright,” but more to be part of the gang than out of passion for the sounds. The only record I recall him singing along with was “What Kind of Fool Am I,” from the Broadway soundtrack LP to Stop The World—I Want to Get Off. (My response to that, had I known about the record at the time, would have been to play the Electric Prunes’ garage-psychedelic classic “Get Me to the World on Time.”) Response to rhythm and soul seemed deeper on my mom’s part, and maybe that was passed on to me, or at least more from her than my dad.

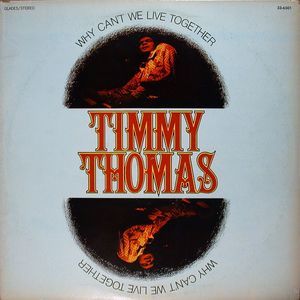

What about my parents’ reaction to my collection, or what I played on the radio? There was virtually none. Again, with hindsight they were likely just too busy working and family-raising to think much about it. The only time my father came into my room to turn the radio down was when, circa early 1973, it was playing Timmy Thomas’s huge hit “Why Can’t We Live Together.” That might not seem like the loudest or rowdiest tune from the time to get upset over, but my radio was directly on the other side of the wall from my parents’ bedroom, and the high organ squeaks were driving him up the wall.

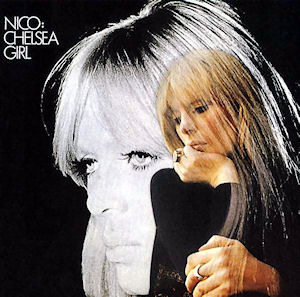

The only time he had a specific comment about a record I was playing was equally unpredictable. On a visit home from college when I was about nineteen, I had Nico’s Chelsea Girl on the turntable. It might have been playing the song “Chelsea Girls.” In comparison to much of the rest of my collection, Chelsea Girl is for the most part a very low-volume, folky LP—and not one that many other people my age in 1981 would have had (not that he would have known that). But Nico’s voice strikes many as pretty peculiar, which is why he walked into my room and asked, “What is he [sic] singing about?”

I was not about to explain that it was about residents in New York’s Chelsea Hotel, where junkies and other hangers-on in the Andy Warhol scene engaged in bouts of depravity. I did point out, however, that low-voiced Nico wasn’t a he, but a she. Puzzled, even uncomprehending, he just shook his head and walked out of the room.

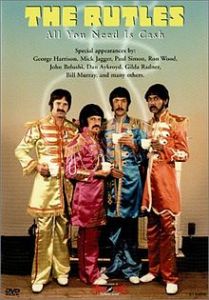

An awkward night of music-watching was spent with both my parents on March 22, 1978. That evening, Eric Idle’s brilliant Beatles satire The Rutles: All You Need Is Cash was broadcast on NBC. This was before the days when home videotaping was common, and that night I had to be traveling with my parents. I insisted that we watch it in our hotel room. Which we did, and neither my mother nor my father—neither of whom were Monty Python or Beatles fans, more out of lack of interest or comprehension than distaste—laughed once. Very few of the inside jokes for which you needed some knowledge of the Beatles’ story to appreciate—and there were many—would have been caught by either of them. My father did redeem himself the next day, when he unexpectedly brought up the scene in which the Beatles play Che (instead of Shea) Stadium, named after Che Guevara. That was pretty funny and clever, he observed.

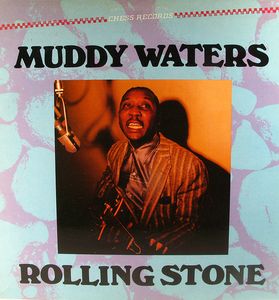

The lone instance in which my mother commented at any length on a record I was playing was equally unanticipated. This was during a brief stay after I graduated from college and before I moved to California. More than thirty years later, it’s hard to envision a time when Muddy Waters’s catalog wasn’t extensive or all that easily available, which is why my Muddy album was a 14-song budget compilation issued in 1982, Rolling Stone. It was a good one, though, with some of his core classics like “I Just Want to Make Love to You,” “Tiger in Your Tank,” “Got My Mojo Working” (the Newport 1960 version rather than the original single), and “Rollin’ Stone” (an “unreleased alternate take”).

When I went downstairs, she asked what I’d just played, and I told her, though I don’t think the name Muddy Waters would have meant anything to her. “That’s my favorite kind of music,” she said, unexpectedly. Music with kind of a Dixieland, New Orleans feel, she elaborated. Yes, I knew full well by then, and had for almost ten years, that Waters was a giant of Chicago electric blues, and had moved to the Windy City from Mississippi. But there was no lecture from me about his history. She was close enough. And with its stop-start rhythms and rolling piano, “I Just Want to Make Love to You,” to take one song from that compilation, isn’t all that far from New Orleans R&B, or even from the earthiest Dixieland.

When it got to the point where I was writing about music for much of my living, and then writing books (not always about music), my parents remained fairly puzzled and uncomprehending about the actual music, but supportive of my efforts. As a final music-related incident worth recounting, when I was about eleven, I’d ask for Beatles LPs for gifts (and did manage to get all of their significant US ones by the end of sixth grade). Around this time my mother remarked to one of her friends, with me present, that it was just a phase I was going through. It wasn’t a phase, however, for me or other rock fans, some quite a bit older than me. She didn’t live to see me teach a Beatles class at the University of San Francisco in front of 200 students aged fifty and older (sometimes quite a bit older), but that would have been quite a full circle to close.

My mother might not have been a rock fan. But she, much more than my father, was a reader of books, with a strong interest in art, which she sometimes taught in schools. On this Mother’s Day, I’d like to think that she passed at least some of that sensibility on to me, even if I’d use it in ways that she could never have predicted.

Mother’s Day – I remember coming into the kitchen and finding my Mother crying as the radio played country music on top of the refrigerator. I was 4 and a half and didn’t understand what had upset her and asked why she was crying and she said she just heard someone she loved had just died ….it was probably

Jan 2nd 1953, and they were playing “I’m so Lonesome I could Cry”.

My experience is just the opposite. Both of my parents contributed quite heavily to my musical preferences. My dad was pure country. My mom loved a lot of the popular music that was out from my earliest childhood reckonings to the time I moved away from home. I’ve made playlists of their favorite music that I transferred to CD-R and gave to my Aunts and Uncles at their funerals. I’ve also made playlists of the music that I associate with both of their families. Those are wider in scope and much more detailed as it runs through my grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins.

Thanks for sharing this. I love reading about people’s personal connections and memories about music, and I wish more people took the time to express those thoughts as well as you have.

I grew up in the 70s/80s, and I have my mother to thank for initiating my musical curiosity. I have memories of being a preschooler, splaying her record albums (Beach Boys, The Mamas & the Papas, etc.) across the living room floor, playing them on my little record player in its white and orange plastic case (more than likely manufactured by General Electric, as my father worked at one of their plants in Erie, PA).

Sadly, the mess I made back then is still in evidence as an adult in my office at home, CDs, albums & 45s (and a laptop with downloads) all over, collecting tunes for playlists for my weekly radio show!