As it was for films and records, there was fear the extraordinary conditions of 2020 would slow down the torrent of book releases. It’s really going to take the next year or two to gauge the total impact, but there was little if any decline in either the quantity or quality of rock history books. Nor the variety: there were biographies, memoirs, genre overviews, gaudily illustrated coffee table volumes, and more.

Some readers might think it will be easier to keep the flow of books up, if your image of the writer is someone who just sits and types until he or she is finished. Maybe the limit to public gatherings and facilities will affect publishing less than film production or record manufacturing, but that’s not the whole story. If writers can’t visit libraries or other historical archives, their research will be handicapped or incomplete for quite some time.

As for speculation that interview subjects will be more available than usual if they’re not performing concerts or staying home far more often, that’s not always the case either. Restrictions on travel mean less in-person interviews and access to personal collections. And not everyone might be in as willing a mood to talk as they usually are, owing to the trying circumstances with which we’re all dealing.

For the last paragraph of bad news, the publishing industry has been badly affected over the last year, like most businesses have. Books have likely been delayed or canceled. It’s harder to get them printed and distributed, and there’s certainly less traffic at physical retail stores that remain open. Even the mail is a less reliable service for ordering books, especially between countries.

All that out of the way, my list for 2020 is nonetheless as long as usual. Also as usual, it doesn’t include several candidates I haven’t checked out, whether it’s because they’re still on my library hold list, or items that can’t currently ship from the UK, or books of which I’m not yet even aware. Notable ones I catch up with over the coming year can at least be reviewed as a supplement to my 2021 list, as I’ve done with a few 2019 titles I’ve listed at the end of this one.

1. Heart Full of Soul: Keith Relf of the Yardbirds, by David French (McFarland). While this high ranking might reflect my extreme interest in the subject matter more than the genuinely decent quality of the book, it’s good (and overdue) to have a biography of the Yardbirds’ lead singer. This book’s on the slim side at under 200 pages, but it doesn’t need to be longer, covering Relf’s story crisply without dragging or embellishing to make for a bigger volume, as often happens in rock bios. It benefits from first-hand interviews with Yardbirds Jim McCarty (also in Renaissance) and Paul Samwell-Smith (who also produced Renaissance’s first album), as well as Relf’s wife and members of his post-Yardbirds bands Renaissance, Medicine Head, and Armageddon.

Relf’s time with the Yardbirds takes up more than half the book, and his story is in many respects the Yardbirds story, as he was the most important member who was with them for all five years of their career. While moody intensity often came through in his vocals and songwriting, this reveals the real-life problems—including depressive episodes, major health threats, and a failing marriage—that also impacted his music and performances. Several of his professional and personal associates stress that he was something of an eccentric loner who was enigmatic and hard to fully know, and ill-suited to longevity in a music business where shunning the rock’n’roll lifestyle doesn’t usually work to your advantage.

The focus remains on the music, Relf getting his due as an underrated singer and harmonica player in particular. There’s plenty of description of his tours and recordings, though just a few surprising factual mistakes slip through (Elektra Records repeatedly being misspelled as Electra, for one). Along with Jim McCarty’s memoir Nobody Told Me!, this finally gets a good Yardbirds-centered book on the shelves, more than half a century after they broke up.

2. Muse, Odalisque, Handmaiden: A Girl’s Life in the Incredible String Band, by Rose Simpson (Strange Attractor). Rose Simpson was part of the Incredible String Band from around mid-1968 to the end of 1970, when the group expanded from the duo of Robin Williamson and Mike Heron to a four-piece with Simpson and Licorice McKechnie. Simpson was Heron’s partner and McKechnie was Williamson’s, though the relationships were open to varying degrees. This memoir goes into her time with the band in considerable detail, from around the time she met Heron through UK and US tours (including a disappointing appearance at Woodstock) and several albums. Along with the detail are well written, straightforward perspectives on the group’s unusual dynamic, which was fluid and rather whimsical, certainly by the standards of fairly successful bands with lengthy recording careers. Simpson, for instance, had barely any musical experience before joining, and wasn’t even that knowledgeable about pop music.

There’s a lot here that will interest any ISB fan, and some general fans of late-‘60s/early-‘70s folk and rock. Highlights include her comparisons of Williamson and Heron’s writing styles (Williamson being more given to cosmic flight, Heron to earthly concerns); observations on recording and working with manager/producer Joe Boyd, who ran the Witchseason roster of which they were a part; their erratic attempts at communal/rural living; the indulgent and in some ways disastrous attempts to branch out into film (with Be Glad for the Song Has No Ending) and multimedia theater (with the performance group Stone Monkey); and the sometimes exhilarating, often exhausting American tours, where they found ecstatic audiences at the Fillmores in New York and San Francisco, but not so much elsewhere. Especially refreshing are detailed memories of the recording sessions in which she took part, as those are often skimmed over or neglected in musician memoirs.

There’s also a lot about the group’s involvement in Scientology, though Simpson never fully committed to it, and it’s her (and some others’, like Boyd’s) view that it wielded a negative influence on the group’s music and lives. There are also encounters, sometimes volatile, with a wide variety of fellow rock celebrities (and cult artists like Vashti, Nick Drake, and Van Dyke Parks), including the Doors, Joan Baez, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, and Keith Moon, who played drums on Heron’s solo album Smiling Men with Bad Reputations. As to the mystery that many fans are most curious about – what happened to McKechnie, who seemed to vanish thirty years ago – Simpson’s clear that she doesn’t know. She does devote several pages to discussing Licorice, leaving the impression her bandmate was an enigma that she and most others couldn’t get to know too well. You can read much more about Simpson and her book in this lengthy story I recently published, based on my recent in-depth interview with her.

3. Ready Steady Go! The Weekend Starts Here, by Andy Neill (BMG). The subtitle of this coffee table production is accurate: “The Definitive Story of the Show That Changed Pop TV.” Ready Steady Go! was the top British rock/pop/soul television program of the mid-‘60s, and in some people’s view the best rock TV show of all time. Over the course of more than fifteen years, Neill interviewed many of the people involved in its production, with the notable exception of the program’s most frequent host, Cathy McGowan. The text alternates between Neill’s history and extensive quotes from many of the producers, hosts, directors, technicians, and musicians involved in the show when it aired from 1963 to 1966. In a coup for a book of this sort, there are extensive multi-page comments from some of the top stars to appear on Ready Steady Go!, including Mick Jagger, Pete Townshend, Ray Davies, Donovan, Eric Burdon, and Lulu.

The volume’s also sumptuously illustrated with many photos (some in color) taken on the set, as well as some vintage press clips, memos, and memorabilia. There’s also a meticulously detailed episode-by-episode guide listing all the performers and (when known, which is usually the case) songs, an appearance index, and even an analysis of the show’s ratings. Why isn’t it #1 on this list, after all that? Some of the comments from the oral histories on the behind-the-scenes production machinations are a little dry and technical, and through no flaws on the author’s part, it’s not quite as consistently compelling a story as the biography and memoir that outranked it. Certainly a good argument could be made for naming it book of the year, however. Just as certainly, it makes you lament the short-term thinking that found just a small percentage of the episodes and footage preserved; most of it’s almost certainly vanished for good.

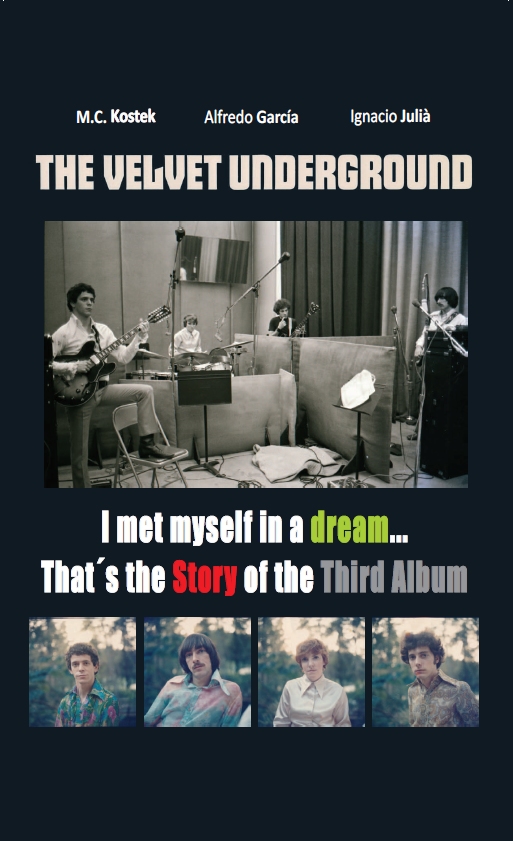

4. The Velvet Underground: I Met Myself in a Dream…That’s the Story of the Third Album, by M.C. Kostek, Alfredo Garcia, and Ignacio Julia (Velvet Underground Appreciation Society). Bearing an October 2019 publication date but certainly unavailable in the US until 2020, this 336-page hefty hardback is limited to an edition of 500 copies. Largely devoted to nearly 200 photos taken of the Velvet Underground in November 1968, it is of course something geared toward very serious fans, especially since it’s $100. But if you are one (and I am one), it’s real interesting, and not just for the pictures. Of course the pictures are the main deal, with about 100 taken as they were recording their third album in TTG Studios in Los Angeles on November 6, 1968, and nearly 80 others at various Southern Californian outdoor locations (probably but not definitely Los Angeles) outside the studio a couple days later. Almost all are in black and white, though eight of the outdoor photos are in color. Besides offering many glimpses of the Velvets at work in the studio section, the outdoor pictures capture their transition to hippie decor, complete with frilly paisley shirts, bell bottoms, and (for Sterling Morrison) orange pants.

There’s not much text, just a couple brief essays that focus on explaining the background of the photos and the third album. But although those have some unfortunate typos, they’re of additional interest for offering a little in the way of obscure information. In particular, the first of the essays describes material on a demo tape performed by Lou Reed (who did most of the singing) and John Cale of Reed compositions in 1965, mailed to himself on May 11 to establish copyright. This is in Reed’s archive in the New York Public Library of the Performing Arts, but not many have heard it so far, and this is the first time I’ve seen it written about, albeit not in extreme depth.

The latter section of the book features lots of reprints of ads, reviews, acetates, tape boxes, and other miscellany related to the Velvet Underground’s self-titled third album and what the band were doing around that time. This again has some rarely seen material, some of which reveals information that hasn’t circulated much if at all elsewhere, like early titles to some songs on the third LP. The paper and reproduction quality are very good, and despite the high price tag I’m guessing it will sell out, if you want to put in your order (through inevitablevucatalogue.wordpress.com) while you can.

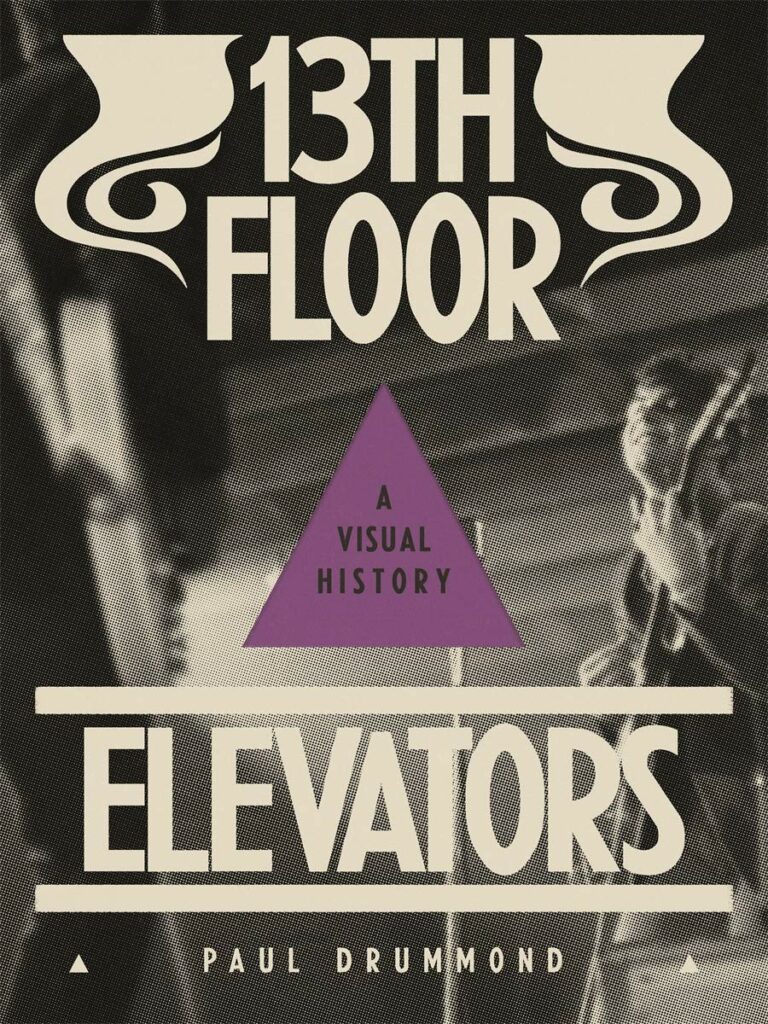

5. 13th Floor Elevators: A Visual History, by Paul Drummond (Anthology Editions). Paul Drummond wrote the comprehensive 13th Floor Elevators biography Eye Mind (published in 2007), and while the text in this new book is interesting, there’s a lot of overlap between what the two volumes cover. Much of it’s devoted to quotes from interviews, done by himself and others, that provided much of the research for Eye Mind. The main reason to check out this new work, even if you have Eye Mind, are the numerous and impressive illustrations in this large-format paperback. There are many photos, posters, newspaper clippings, ads, letters, documents, and other memorabilia related to the Elevators’ career, much of it never published before to my knowledge, and a good deal of it in color. The extensive captions go into a great deal of detail about the graphics, sometimes with quotes from people who were there. It fully lives up to the “visual history” promised in its title, though you should go on to read Eye Mind if you want a fuller history of the Elevators.

That recommendation dispensed, here are a couple criticisms that are small in the large picture. The sole Elevators interview printed during their lifetime (dominated by Tommy Hall), from the December 1967 issue of the Houston magazine Mother, is reproduced here in its entirety. Great, except the pages are so small they’re hard to read; I managed, but I think an appreciable number of readers won’t. And sure the 13th Floor Elevators have a large cult following, but the text’s assertion that their second album “Easter Everywhere’s importance as the [italics included in the book] psychedelic album of the period has now been fully recognized” is unwarranted. By whom? A few critics and devoted fans? More fully by the general music community than Sgt. Pepper, The Doors, Piper at the Gates of Dawn, Are You Experienced, or Surrealistic Pillow? The 13th Floor Elevators were a good and certainly very interesting group; there’s no need to puff up their historical status with that kind of overkill.

6. Savage Impressions: An Aesthetic Expedition Through the Archives of Independent Project Records & Press, compiled by Bruce Licher and Karen Nielsen Licher (P22 Publications). Bruce Licher is known for constructing odd, spooky, primarily instrumental soundscapes in his alternative rock bands, of which Savage Republic and Scenic are the most well known. He’s also known, and not solely within the indie rock world, for his distinctive letterpress design work. It’s adorned records by groups in which he’s played, acts on the Independent Project label, and other record releases, posters, stamps, and other ephemera, extending to record company stationery. His visuals and layouts often bridge lettering both ancient and futuristic, often incorporating haunting images, photos, and unpredictable splashes of color. His perfectionist eye for detail extends to this 236-page coffee table book, which lays out an astonishing wealth and variety of his artwork, from the first Independent Project releases in 1980 to the present.

Interspersed throughout the book are essays on his various stages of development, from the Savage Republic era and his time in an ancient downtown Los Angeles building to his moves to Arizona and the Sierra Nevada. Detailed captions give the background to all of the reproductions, and while the text is straightforward, some amusing stories surface, like how he arranged to put stamps of his own design alongside official US stamps on mail, or how his stint designing poetry book covers for Penguin ended as poets felt they looked too much like small-press efforts (“the poets actually wanted glossy full-color covers!”). The range of his clients expanded from IPR-related projects (including early releases by Camper Van Beethoven) to bands like R.E.M. and labels like A&M Records, Licher eventually using more computer technology in his work without compromising the individuality of his output.

At $79.95, this is an expensive purchase, though justified by the high quality of the visuals and production. A 350-copy deluxe edition, including a bonus LP and a few other extras of less note, is already sold out. The LP, with fourteen previously unreleased tracks from various Licher musical projects spanning 1980 to 2019, is highly worthwhile, and reviewed separately in my post covering the top reissues of 2020. Read my story on Savage Impressions and Bruce Licher, based on an extensive recent interview with him, here.

7. Time Between: My Life As a Byrd, Burrito Brother, and Beyond, by Chris Hillman (BMG). In keeping with his low-key team player persona in most of his bands, Hillman’s memoir is a straightforward, unflashy, likable recount of his career. The Byrds and the Flying Burrito Brothers have been covered extensively in several books, most notably Johnny Rogan’s huge Byrds volumes and Hot Burritos, which Hillman himself co-wrote with John Einarson. There isn’t an enormous amount you’ll learn about Hillman’s most famous work if you’re familiar with those books, and with the history of his groups in general. But while there’s more on the Byrds/Burritos than anything else, he does cover less familiar ground, including his teenage folk-bluegrass years (scarred by the suicide of his father), Manassas, the Souther-Hillman-Furay quasi-supergroup, McGuinn Clarke & Hillman, and the country act the Desert Rose Band, in which he served as leader.

If you’re looking for some less-traveled Byrds stories, while there aren’t a whole lot, it’s interesting to read how he wrote “So You Wanna Be a Rock’n’Roll Star” with Roger McGuinn, which he clarifies was not specifically about the Monkees, and how playing on demos for South African jazz singer Letta Mbulu gave him some impetus to start writing and singing his own songs. As to the controversy over McGuinn replacing some of Gram Parsons’s lead vocals on Sweetheart of the Rodeo, Hillman simply feels “Roger’s vocals were better in the end,” the album including “just the right balance of singers.” It’s not a secret as he’s spoken and written about this in the past, but Hillman’s memories of Parsons are decidedly mixed, combining great admiration of his talent and charm with disappointment at his unreliability and egotism.

The post-early-‘70s years don’t make for as much interesting reading, but Hillman knows not to dwell on the less celebrated parts of his career and maintain a reasonably interesting flow. There are some passages on his Christian faith, but not many, and these aren’t unduly obtrusive. Dry humor and realistic observations on the music business emerge from time to time, as in this summary of manager Larry Spector’s supplying the inspiration for the Burritos’ “Sin City,” in which he’s targeted: “At least he gave me something after robbing me blind.”

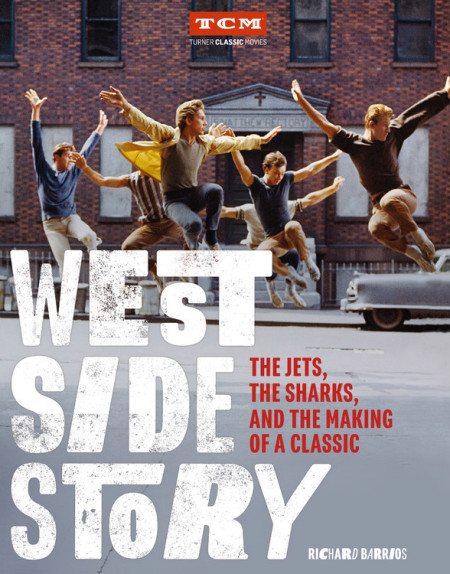

8. West Side Story, by Richard Barrios (Turner Classic Movies). Film musicals aren’t mainstays of my record collection, and books about them haven’t made appearances on my lists. West Side Story is the only film musical I really like, however, and this is a good book about how it was made, with plenty of photos. This follows its genesis as a Broadway play to the 1961 film, which was a stormy collaboration between directors Jerome Robbins (who was fired partway through the production as he was taking too much time and spending too much money) and Robert Wise. There’s a lot of back-story to how the cast was chosen, how the New York scenes were filmed, and how cast and crew coped with setbacks include cost/time overruns, quite a few physical injuries, and some tension between key actors. There are also sections on how it was promoted and received by critics and audiences, as well as differences between the play and the movie. I would have liked some more specific description of how the rumble scene was filmed, and didn’t need a final chapter about the recent remake (now not scheduled for release until late 2021). But overall, this is a more consistently interesting and crisply written volume than almost anything on this list.

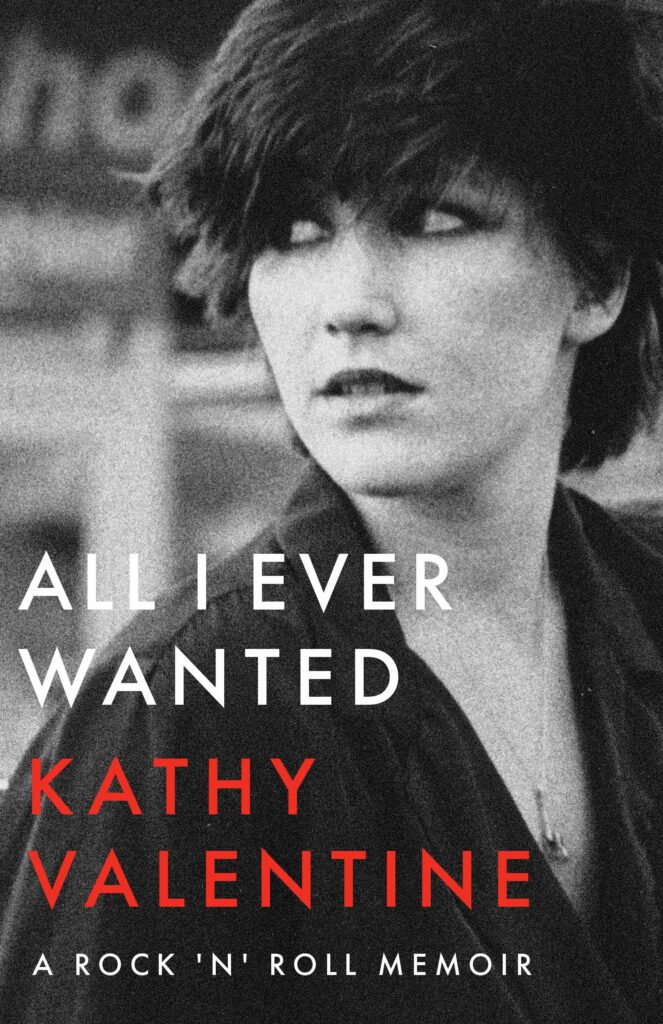

9. All I Ever Wanted: A Rock’n’Roll Memoir, by Kathy Valentine (University of Texas Press). The autobiography of the Go-Go’s bassist and sometime guitarist concentrates almost exclusively on her life through 1990, when the group reformed after breaking up only four years after she joined. It’s a well written and, more unusually for rock memoirs, very well balanced account, covering recording, performing, songwriting, guitar playing, band and record business dynamics, and personal life and passions without leaning too hard or too long on any aspect. The chapters on her unconventionally permissive upbringing in Austin are about as worthwhile as those on the star period, and disturbingly frank in a couple reports of sexual assault. Her time with Carla Olson in the Textones (who recorded the original version of “Vacation”) is given its due, Valentine observing the band couldn’t break through in part because they were so different depending on whether they were doing Olson’s or Valentine’s songs.

Valentine’s rise to superstardom was rapid after she replaced Margot Olavarria in the Go-Go’s, and she recounts their tours, hijinx, and hits enthusiastically without overdoing it. It’s interesting to read how the band were initially highly disappointed in the sound of their debut album, finding it too clean. As she admits, “My opinion changed proportionally with the increasing sales.” And she has the perspective to add, “Sometimes I’ve wondered what it would be like to re-record Beauty and the Beat the way I would like it to sound, with thick, full tones and textures. But then I remember the ephemeral spirit infusing the recording process, the anticipation and joy of a fleeting time, and I know something else was captured that could never be reproduced.”

And then, the downside: not enough time to concentrate on writing strong material for follow-up albums; disputes over songwriting credits, publishing money, and management; getting coerced into publicity that exploited their perky image; and the breakup, to her shock, of the band in the mid-1980s, as she anticipated getting ready to record an album with producer Mike Chapman. She had more trouble than the other Go-Go’s in launching a separate career, and those difficulties are elaborated, as are her affairs with Chapman and Clem Burke. Drugs and alcohol were also a problem with some Go-Go’s, and there is, as there are in so many rock memoirs, a section devoted to her time in AA and recovery. The post-1990 years are briefly summed up in an epilogue, which might have been a tough call if she wanted to tell stories about the reformed Go-Go’s, their lawsuits, and their reunions. To be harsh, if so it was the correct one, as what’s here is solid without much of the post-peak hangover that makes the latter half of many memoirs tough sledding.

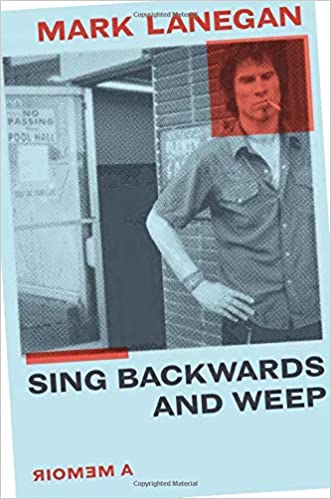

10. Sing Backwards and Weep: A Memoir, by Mark Lanegan (Hachette). If you’re interested enough to be reading a list like this, you’ve probably read numerous musical memoirs that at least in part document harrowing descents into substance abuse. Even by the standards of the most graphic of those, Lanegan’s is exceptionally grim and detailed. It’s often gripping, but there will be times when you might wish it wasn’t as graphic, or at least that the story moves along quicker to the usual rehab and redemption. In this case, it doesn’t come until the very end (and more than twenty years ago), after he’s spent much of the 1980s and 1990s looking to score, even and especially on lengthy tours throughout North America and Europe. Along the way, he helped drag a number of friends and acquaintances along the same path, whether doing drugs with them, selling drugs to them (and to many strangers), or letting lowlifes crash in his pad because they shared or helped him obtain what he wanted and needed.

Is there much about music amidst the chaos? Yes, though especially as the tale grinds on, maybe there should have been more. Lanegan has lots to say, much unflattering, about Screaming Trees, and also about his early solo career, which was considerably more vital in establishing his reputation as a dark alternative rock singer-songwriter. He also has much to say, again often though not always unflattering, about lots of pretty well known figures in the rock world with whom he was associated. That includes the heads of Sub Pop Records (who used a cover shot on his solo debut without his consent, and unceremoniously dumped him by handing his tapes back for his incomplete second album – before asking him back on the label), Nirvana (whose bassist Krist Novoselic asked to join Screaming Trees, though Lanegan turned him down), and Courtney Love (who paid for much of his expenses as he went through rehab). There are also weird and sometimes grisly anecdotes about a host of others, ranging from Greg Sage of the Wipers and 4AD Records chief Ivo Watts-Russell to A&R guy Bob Pfeifer, Liam Gallagher of Oasis, film director David O. Russell, and Jeffrey Lee Pierce. The music business is depicted as a harsh and capricious place, though maybe it often has to be to handle talents as volatile as Lanegan’s.

Lanegan doesn’t make excuses for his behavior, recounted in a straightforward and unflinching fashion, though his troubled family upbringing is discussed. Also there is not much moralizing about drugs or the redemptive power of rehab, and the expected frustrating near-misses when he seemed on the verge of escaping drug hell on his own. There’s not a great deal of self-introspection about the damage he wreaked on himself and others, though in some ways the story speaks for itself.

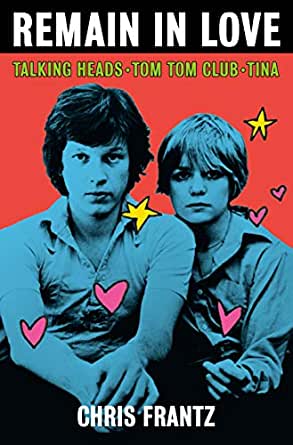

11. Remain in Love: Talking Heads, Tom Tom Club, Tina, by Chris Frantz (St. Martin’s Press). Talking Heads/Tom Tom Club drummer Frantz’s memoir concentrates on just what the subtitle says, his wife Tina Weymouth being of course bassist in both of his bands. Although there’s quite a bit (some would say too much) about his childhood/teenage years and family, the core is devoted to the formation and rise of Talking Heads, especially in the mid-to-late 1970s. It’s pretty well known by now that three-fourths of the group have had different views than singer David Byrne about the nature of the individual and collective contributions to Talking Heads’ sound. Frantz states in his intro that he wants his book to present his view on the “the true inside story,” which is different than some others that have circulated over the years.

If you want examples of Byrne’s at times asocial and inconsiderate behavior, there are quite a few, dating back to when the band formed in Rhode Island. However, Frantz also credits Byrne with a lot of talent as a singer, performer, and songwriter, though they (and Brian Eno) had substantially differing views of how composer credits should be apportioned. There are also numerous inside stories of encounters, close and passing, with plenty of figures from the CBGB’s and beyond. Some are very complimentary portraits (Lenny Kaye); some are mixed but overall quite positive (Sire Records chief Seymour Stein, CBGB’s owner Hilly Kristal). Some are mildly unflattering (Patti Smith), and some very unflattering (John Martyn, who though far removed from Talking Heads stylistically, crossed paths with them when Martyn was recording). And there are up-and-down interactions with people that could be pretty strange, like Lou Reed, Phil Spector, and Johnny Ramone.

But much more of the book covers Talking Heads/Tom Tom Club’s music and creative processes, both onstage and in the studio. The book hits its best stride when discussing how they aimed to make their recordings different from their live shows; how they wanted to make each album different; and how Frantz and Weymouth wanted to make their Tom Tom Club group different from Talking Heads, only getting a deal with Seymour Stein after they’d started to take off in Europe. The stories of how rough it was living in the Lower East Side when Talking Heads started out are pretty gripping, and the accounts of life at CBGB’s (musical and otherwise) when a punk/new wave scene started to blossom there pretty insightful. For all these reasons, Talking Heads fans, and fans of the ‘70s New York new wave scene in general, will find much to interest them. You can read more about it in my interview with Chris Frantz about the book.

12. The Ox: The Authorized Biography of the Who’s John Entwistle, by Paul Rees (Hachette). Entwistle was the least colorful member of the Who, though of course he had more competition than a guy in any other band would have when matched with Keith Moon, Pete Townshend, and Roger Daltrey. His stock-still, deadpan persona was an important part of what rounded the group’s image off, but in all his life makes more for a reasonably interesting story than a sensational one. That’s what you get with this bio, which covers both his musical contributions (his virtuosic bass playing and offbeat, often macabre songwriting) and his surprisingly tumultuous personal life, given his stolid persona. While in some respects he was a normal family man, he also indulged in typical rock star excesses – drinking a lot and drugging his share, spending money on countless indulgences, and womanizing, leading to his early death in middle age.

The book benefits from excerpts from a memoir Entwistle started but didn’t come close to completing, as well as cooperation from some close associates, including his son and two wives (but not Townshend or Daltrey). Much of this covers ground that will be familiar to Who fans, but it’s told well and does have fresh interviews with friends and colleagues who haven’t ever or often been quoted. There could have been more about his music, specifically his songwriting – interesting Who B-sides he wrote like “Heaven and Hell” and “Doctor Doctor” are mentioned only in passing. And how can you not write about his compositions “Silas Stingy” (about a guy who hoards so much he ends up with nothing at all) and “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” (possibly about his pal Moon) considering the obvious real-life personality traits they document?

While plenty of rock bios/memoirs document a descent into musical mediocrity and personal chaos, Entwistle’s was sharper and more depressing than most. His tours outside the Who were poorly received, and his solo albums largely uninteresting. The girlfriend with whom he spent his final years is almost universally vilified as a corrupting influence. The post-Moon years only take up the last third or so of the book, which will be a fairly worthwhile read for Who fans, but not on the level of Tony Fletcher’s Moon biography or the memoirs of Townshend and Daltrey.

13. Harlem of the West: The San Francisco Fillmore Jazz Era, by Elizabeth Pepin Silva and Lewis Watts (Heyday). For about twenty years after World War II, San Francisco’s Fillmore district was the center of the city’s African-American cultural life. This book deftly combines more than 200 photos with oral history quotes from people who were there, and some explanatory background text by the authors. Many local jazz, blues, and R&B musicians—whether residents or touring—played in Fillmore clubs, and many of the pictures the authors uncovered document performances. Some famous figures are seen (not always performing), from Chet Baker and John Coltrane to Dizzy Gillespie and Billie Holiday; some were more local/regional in their principal success, like Sugar Pie DeSanto and Saunders King; and some are not just obscure, but unidentified. There are also pictures of local life, whether club audiences, bars, district businesses, informal get-togethers, and the top neighborhood record store.

For all its liveliness, the Fillmore black music scene didn’t develop too much of a distinct or influential regional sound. Maybe it was too small, and some of the top homegrown musicians, like Etta James, moved elsewhere to journey to stardom. Also, even as it was thriving, urban redevelopment schemes were underway that razed much of the area, relocating many residents and destroying quite a few local businesses. And while San Francisco wasn’t as rampantly prejudiced as many US cities, even in its heyday, musicians and residents suffered blatant discrimination in obtaining work and housing. This is also covered in the text and some photos, serving as a sober record of how an ethnic enclave can be weakened and in some ways decimated by insensitive government policies. Read more about the book in my story after it was published, based on an interview with the authors.

14. Let’s Stomp!: American Music That Made British Beat 1954-1967, by Peter Checksfield (peterchecksfield.com). Peter Checksfield’s been cranking out valuable reference books covering pre-1980 (and especially 1960s) British rock over the past couple of years, with volumes documenting the TV/movie/promo films of British ‘60s rockers, the Beatles, and the glam era. This goes into different territory, listing more than 2000 American songs that were covered by British artists between, as the subtitle says, 1954 and 1967. The original versions, and all the UK cover versions Checksfield could find, are documented with original release information. The UK covers of specific songs include not just the first or best-known ones, but all of them, even if there were nearly a dozen (as there were, for instance, for some Chuck Berry compositions).

It’s not just a catalog-like volume of lists. Each of the covers is briefly but vividly described and evaluated, with stars awarded to the one Checksfield judges the best. When a cover is clearly based on a version that’s not the original, the likely actual recording that served as an inspiration is noted. When a song that’s been retitled from the original, or adapted from the original even if it bears different songwriting credits (not too rare an occurrence, alas), that’s noted too. Room is made for some artists from other countries who were based in the UK, like the Walker Brothers, P.J. Proby, and the Bee Gees (born in the UK but based in Australia for the first few years of their recording career). The lists of covers get into some really obscure recordings, including non-UK-only releases and even some versions that only circulate unofficially, or as video performances.

Checksfield is pretty generous in his assessment of the quality of many of the covers—more generous than I would be, in many instances. That’s not such a big deal, however, since his descriptions of the sounds are pretty accurate, and his designations of favorites usually on the money. The volume also makes it plain that, as much as British Invasion groups from the Beatles on down were rightfully hailed for digging deep into obscure US recordings for much of their repertoire, that had been happening with UK artists going back to the mid-‘50s.

His documentation made me aware of some obscure British ‘60s releases (including anthologies of BBC and live recordings) I’d never been aware of. It also made me aware of many original versions I’d not only never been aware of, but never suspected. To take just two examples, I’d always figured Herman’s Hermits “The Man with a Cigar” to be an attempt by someone to drag them into more sophisticated lyrics, not realizing it was a 1963 soul single by Lew Courtney. Simon Dupree’s “Kites,” a 1967 psychedelic hit, turns out to have first been done by the Rooftop Singers, of all people.

If you want to pick on such a mammoth work for occasional omissions, there are a few. The Small Faces’ cover of Marvin Gaye’s “Baby Don’t You Do It” is listed, but not the ones by Scotland’s finest ‘60s group, the Poets, or the Who (who didn’t release theirs at the time, but whose 1964 demo version came out on the expanded Odds and Sods CD). Nor is the Kinks’ 1967 BBC cover of Spider John Koerner’s “Good Luck Child” (which they retitled “Good Luck Charm”). Some artists who began overseas but relocated to the UK aren’t covered, most notably the Easybeats. And though early 1963 Rolling Stones demos (all cover versions) are noted as unreleased, actually they did officially come out on the 80-track version of the 2012 GRRR! compilation. These are tiny flaws, however, in a valuable reference work, and maybe can be corrected in an updated edition.

15. Looking to Get Lost: Adventures in Music & Writing, by Peter Guralnick (Little, Brown). Guralnick is one of the pre-eminent writers on American roots music, most notably via his collections Feel Like Going Home and Lost Highway; his southern soul history Sweet Soul Music; and biographies of Elvis Presley and Sam Phillips. Like Feel Like Going Home and Lost Highway, this is a collection of essays and articles, most on prominent musicians like Joe Tex, Lonnie Mack, Delbert McClinton, Tammy Wynette, Chuck Berry, Solomon Burke, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Howlin’ Wolf. There are also a few pieces that go outside his usual format, including an interview with Eric Clapton; stories on (non-music) writers Lee Smith and Henry Green; and a couple essays going into his personal and family history. There are also portraits of key non-recording stars like songwriters Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller; Presley manager Colonel Tom Parker; and blues songwriter Willie Dixon. Most of these draw upon first-person interviews with the subjects, with whom he often hung out at recording sessions, offices, concerts, and such while gathering material.

Guralnick radiates such decency and sincere passion that I’m not eager to supplement that summary with some criticisms. But his portraits are often overzealous in their championship of heroic qualities in these men and women’s lives and art. This enthusiasm also spills over into the how the stories are written, with extraneous asides and breathlessly long sentences. From his report on sitting in on sessions for Maine country singer Dick Curless’s final album in the mid-1990s: “But it was his own quiet certitude most of all that established the mood that quickly took hold and convinced us unquestionably (though I must admit, the question still lingers in my mind, did Dick himself need any convincing?) that we had all set off on a spiritual journey, a journey that was likely to lead to exaltation and grace if we were simply willing to commit ourselves to it in our own way, with or without explicit belief.” I don’t think I could have gotten that worked up even if I’d sat in on the sessions for the Doors’ first album.

This has plenty of info and insights on some major (and minor, as most would classify Curless) figures in blues, rock’n’roll, soul, and country music. Feel Like Going Home and Lost Highway are more focused and more stylistically restrained, though hardly unenthusiastic. That makes them better reads for me, even though I don’t share his passion for all of the musicians he celebrates.

16. A New Day Yesterday: UK Progressive Rock & the 1970s, by Mike Barnes (Omnibus). At nearly 600 pages, this is a hefty history of a major rock genre that has never before been honored with such a comprehensive book. It’s not so much a straight chronological history, however, as it is centered around chapters on specific UK prog acts, most of them well known. Yes, Pink Floyd, King Crimson, Genesis, Jethro Tull, Mike Oldfield, and Emerson, Lake & Palmer are obvious suspects, and a lot of the more cultish but prominent ones are covered too (Soft Machine, Van Der Graaf Generator, Gong, Henry Cow, Caravan). There are also sections on prog festivals, its coverage in the rock press, drug use and fashion among prog musicians and fans, and prog’s relationship with British folk-rock, among other sub-topics.

The book’s chief asset is the fresh research, as Barnes did first-hand interviews with many of the musicians, including a lot of the stars as well as the lesser known figures. However, the separate chapters on numerous artists does mean that none of them are documented in extreme depth, and some represented elsewhere by comprehensive books devoted solely to a specific act. Personally I would have liked more description and analysis of the interrelationships between different prog groups and movements, and how the huge genre as a whole grew and morphed over the course of about a decade. Also maybe more in-depth Q&A interviews, of which there are only a few: the one with Sonja Kristina of Curved Air is not only extremely interesting, it’s my favorite part of the book. On the whole, of course this will have info (and knowledgeable perspective from the author) that will be valued by any prog rock enthusiast. Many would have wanted more (or sometimes less) coverage of specific favorites, but it’s hard to get a book published that runs more than 600 pages, and such broader coverage would have made that necessary.

17. Have a Cigar! The Memoir of the Man Behind Pink Floyd, T. Rex, the Jam, and George Michael, by Bryan Morrison (Quiller). The title is overly grandiose: Bryan Morrison was indeed involved in the business side of all of those acts, but sometimes for a short while, and more on the publishing/booking side than the personal managerial one. Written in the early 1990s, this was shelved when Morrison didn’t like how it had been rewritten by a publisher. Ten years after his 2008 death, it was edited by Barry Johnston and, with a few explanatory notes, issued in 2020. Boring technical note: it has a 2019 publication date, but certainly wasn’t available for purchase until 2020, hence its inclusion on this list.

This is a quick, breezy, and fairly entertaining read. It’s almost like an entertainment world equivalent to the O Lucky Man! film in how Morrison bounced from project to project (not always in the music business), often finding great success, and sometimes going bankrupt or nearly dying. There are amusing, if sometimes depressing, stories of the inside machinations of the rock world, whether it’s an unhinged Syd Barrett biting Morrison’s hand to the bone; Roger Waters dispassionately firing Morrison as Pink Floyd approached ‘70s stardom; and Paul Weller blowing the Jam’s chance for US success by dismissing a chance for an interview with a row of high-powered American media to talk with fans. Although the Pretty Things are not cited in the book’s subtitle, they were a vital stepping stone to Morrison’s career as the first band whose affairs he handled (as their co-manager in their early years).

This isn’t all that long (about 220 pages with a good share of blank chapter-dividing pages), and there’s a sense that Morrison could have said a lot more about his clients, who also included (at various stages) Robin Gibb, Keith West, and Wham! There’s also a feeling of impersonal distance from the music, though his enthusiasm does sometimes surface, and not always like you’d expect: he unreservedly hails Barrett’s pair of cult solo albums as classics, and accurately notes that “the songs he had written were wonderful and spoke of simplicity.” And in common with the autobiographies of numerous music business moguls, he gives equal treatment to a wide circle of artists that no reader will like equally: there really isn’t too much overlap between Syd Barrett and George Michael fans, for instance. Then there’s the issue of how he devotes quite a bit of space to non-musical endeavors – his investments in the fashion and design world, and his passion for polo – that rock fans might not want to bother with. It’s a volume for British rock specialists, particularly those with a bent for the kind of emerging underground rocks Morrison somehow tended to work with, though he didn’t seem like too much of a cultural radical himself.

18. Peter and the Wolves, by Adele Bertei (Smog Veil). Originally published in 2013 in a limited edition of 200, this slim memoir is now more widely available in a revised version. It’s slim because, although Bertei has had a long career in music (most famously with the Contortions), film, and writing, this focuses almost wholly on her experiences with Peter Laughner in the mid-1970s as she began to seriously pursue music. The subject of a recent box set that was also issued by Smog Veil, Laughner is one of rock history’s foremost examples of a talented musician, singer, and songwriter who didn’t reach his potential, with barely any released recordings before his death in his mid-twenties in 1977. Bertei mixes memories of her own artistic awakenings as she emerged from a troubled adolescence with her experiences with Laughner, who was kind of a mentor to her when they were roommates in Cleveland.

In some ways this was an exciting time to be around Laughner and the Cleveland underground rock scene, as he was a key member of Rocket from the Tombs and early Pere Ubu with David Thomas. Laughner did much to encourage her entry into the world of professional musicianship and increase her knowledge of rock music in general. At the same time, he was prey to the demons of substance abuse and rock and roll excess as much as any dissolute superstar, though without the accompanying commercial success and widespread recognition. It’s disheartening to read not only tales of his reckless behavior (some involving guns), but also how he sabotaged his prospects in numerous musical projects, almost as if he had a fear of success even on an underground level.

Bertei celebrates his qualities, but doesn’t shirk from detailing the sordid and tragic aspects of his life, although she transcended these to make her mark on the New York underground. It’s a worthwhile account, illustrated with some vintage photos, but a frustrating one, as it reads like the first part of what should be a full memoir. Bertei notes in the acknowledgements that this was originally meant as part one of a lengthier memoir in progress, and one hopes she completes that in the future. You can read my interview with Bertei about the book here.

19. It Ain’t Heavy, It’s My Story: My Life in the Hollies, by Bobby Elliott (Omnibus). The memoir by the Hollies’ drummer doesn’t make this list on its literary merit. So be warned: unless you’re a big fan of the Hollies, you won’t be interested. And even if you are a pretty big fan of the Hollies, like I am, you’ll likely find it a pretty matter-of-fact and dry read. Even considering the large print, there’s surprisingly little of high interest in this 320-page book, often told in a “then this happened, then that happened” manner. Surprises are few, among them his story of how Paul McCartney tried to get him to join Wings, or running across Pretty Things drummer Viv Prince in a London gutter. But there’s a shortage of commentary on songs, recording sessions, or just what set Elliott’s fine, distinctive drumming apart from his contemporaries; he does express his admiration for jazz, but there aren’t many specific examples of how it was applied to the Hollies’ pop-rock. Nor is there much reflection on the personal and musical dynamics of the group, though there’s some insight into what drove Graham Nash to leave in the late 1960s, and lead singer Allan Clarke’s mercurial comings and goings in the ‘70s.

There’s enough in the way of musical and touring tidbits to keep you going if you’re looking for more info on the Hollies, who still don’t have a good book dedicated to their career. And, thankfully, the post-‘70s years, when they’ve pretty much been a nostalgia act, are dealt with in just a few pages. But I think the average British Invasion fan, and even some serious Hollies fans, are going to be disappointed. You want a good memoir by a top British drummer who emerged in the mid-‘60s? There were two, actually, in 2018: Jim McCarty’s Nobody Told Me: My Life with the Yardbirds, Renaissance & Other Stories, and Kenney Jones’s Let the Good Times Roll: The Autobiography.

20. Do You Feel Like I Do? A Memoir, by Peter Frampton with Alan Light (Hachette). Kind of like I wrote about the Elton John book in the 2019 section of this list, I’m interested enough in Frampton’s career to pick up a copy of his memoir from the library, though even a little less of a general fan of Frampton’s music. Certainly I don’t have to hear Frampton Comes Alive! again. But remember he did have a professional history that predated that monster by about a decade, including stints in the Herd (who had some late-‘60s UK pop success without breaking the US) and Humble Pie. And his mid-‘70s megastardom is sort of interesting from a sociological point of view, if not extremely so from a musical one.

To bring up the Elton John parallel again, Frampton’s autobiography is similarly likable and for the most part highly readable, though it runs out of more and more steam the farther it gets from the 1970s. In accordance with my personal tastes, the most interesting parts are the early ones, especially his memories of being sort of shepherded into pop-rock stardom with the Herd’s early songwriters/managers, and working with Steve Marriott in Humble Pie. He leaves the impression he never cared too much about stardom and wasn’t enthused by attempts to exploit his looks to gain that, prioritizing his guitar playing and songwriting. That makes it seem that Frampton Comes Alive! was almost an accident that he regrets, though the details of how the big hits were written and how that got expanded into a double LP from its intended single disc here. So are the details about various financial business troubles that have hindered him (especially with ex-manager Dee Anthony), as well as some illnesses and struggles with substance abuse.

The final chapters, like many celebrity memoirs (including, again, Elton John’s), get into steadily less compelling collaborations, tribute/concept projects, comeback tours, resolution of family conflicts, and such. Still, he retains a humble authorial voice, even as a recent rare illness is making it harder and harder for him to continue performing. Interesting trivial note: he turned down a chance to join Grand Funk in the early 1970s, and an invitation to join the Who in the 1980s.

21. Indian Sun: The Life and Music of Ravi Shankar, by Oliver Craske (Hachette). Craske collaborated with Shankar on the sitar player’s 1997 autobiography, but this is an entirely separate volume that’s a straight biography. It’s an extremely thorough one, running more than 600 pages, and draws on interviews with more than a hundred people, including Shankar and many of his closest family members and professional associates. The detail of his compositions, recordings, film scores, and performances can be technical, using a lot of terms in Indian music that may be unfamiliar to readers not versed in the form, though the terminology is explained in a brief preface. The intensity of the documentation might be hard to wade through for some more casual Shankar fans and listeners.

But if you’re willing to spend more time than is the norm for a biography, a lot of material focuses on the more human side of his life and art. Musically, this includes coverage of his wide influences on and interactions with the international music world, George Harrison and the Byrds foremost among them. Less known, but also discussed at even-handed length, are his numerous fans in the jazz world (notably John Coltrane) and other genres, including occasional collaborator Philip Glass. As for his personal life, his numerous romantic liaisons are examined, as are careers of his offspring, especially daughters Norah Jones and Anoushka Shankar. Whatever your knowledge of his music, the sheer scope of Ravi Shankar’s life will impress you, from international tours as a boy to an astonishing number of recordings, famous concerts, and meetings with celebrities and heads of state throughout the world. In addition to interviews, the author was also able to access a great deal of archival material that helped clear up the essentials on Shankar’s background and rise to global prominence.

22. Leonard Cohen: Untold Stories: The Early Years, by Michael Posner (Simon & Schuster). Posner interviewed more than 500 people for a mammoth, three-volume Leonard Cohen oral history. This first volume covers his life until the end of 1970, from his formative years in Montreal through his rise as a poet and novelist and, starting around 1966, his transition to acclaimed singer-songwriter. There are many stories in this 482-page book, some from close associates like producer John Simon, others from friends and peers who’ve seldom or never had their memories published.

There’s a ton of content here. But it reminds you how, unless you’re devoted to collecting as much info as you can, biographies that distill such interviews into part of a focus on the essentials usually make for better reading. Some of the tales are mundane, and there’s a lot of repetition of similar sentiments, particularly those testifying to Cohen’s gracious character, formidable intellect, and prolific womanizing. For those such as myself interested in his music above all else, the sections about his early songwriting, records, and concerts are by far the most interesting.

Even some of the stories that are known to serious Cohen fans will be pretty obscure to many readers. Those include attempts by little known folkies the Stormy Clovers and Penny Lang to do the earliest versions of “Suzanne,” or the several songs he’s known or rumored to have written about Nico. But for a better and more readable overview of Cohen’s career and most important achievements – even considering that only a part of it covers the period documented in this book — I’d recommend the best biography of the singer, Sylvie Simmons’s I’m Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen.

23. Ted Templeman: A Platinum Producer’s Life in Music, by Ted Templeman as told to Greg Renoff (ECW Press). Templeman had a very successful career as a producer in the 1970s and 1980s, gaining his biggest hits with the Doobie Brothers and Van Halen. That means I’m not nearly as interested in the subject as I am for almost any other book on this list, but it has its value, even for someone like me who’s not a fan of those acts. First, Templeman had close ties to some artists who do interest me. He co-produced Van Morrison’s Tupelo Honey and Saint Dominic’s Preview as he was starting his production career. Before that, he was in sunshine pop group Harpers Bizarre, and even before that, Santa Cruz group the Tikis, who recorded for San Francisco’s Autumn label in the mid-1960s. His stories of those times hold my attention more than the other sections, and his memories of Morrison will be sought by any Van fan, especially as he’s more positive about the singer than many of his associates are, though he acknowledges and entertainingly details Morrison’s eccentricities.

But the post-Van parts, which take up more than half the book, are for the most part worthwhile too. Even if you’re not particularly big on the Doobies and Van Halen, you get a lot of behind-the scenes stories about how their familiar hits were made. More notably, Templeman has a lot of insights into the shifting role of a producer, combining psychology, respect, authority, technical know-how, commercial considerations, and more in a complicated juggling act. There are also illuminating stories about the inner dynamics of Warner Brothers Records, for whom Templeman worked (and also served as a vice president). He was a close friend and associate of Lenny Waronker from the time Waronker worked with Harpers Bizarre, and there’s plenty of commentary about power brokers at Warners like Waronker and Mo Ostin. Like many artists, Templeman fell victim to substance abuse; unlike many memoirs, this doesn’t spend a whole lot of pages on it, or belabor the descent and recovery. At 460 pages, this is pretty long, but pretty well written, with little extraneous material. There’s also some coverage of other artists he worked with (especially Nicolette Larson, Sammy Hagar, Carly Simon, and Montrose), though the ones mentioned earlier in this review take up the bulk of the text.

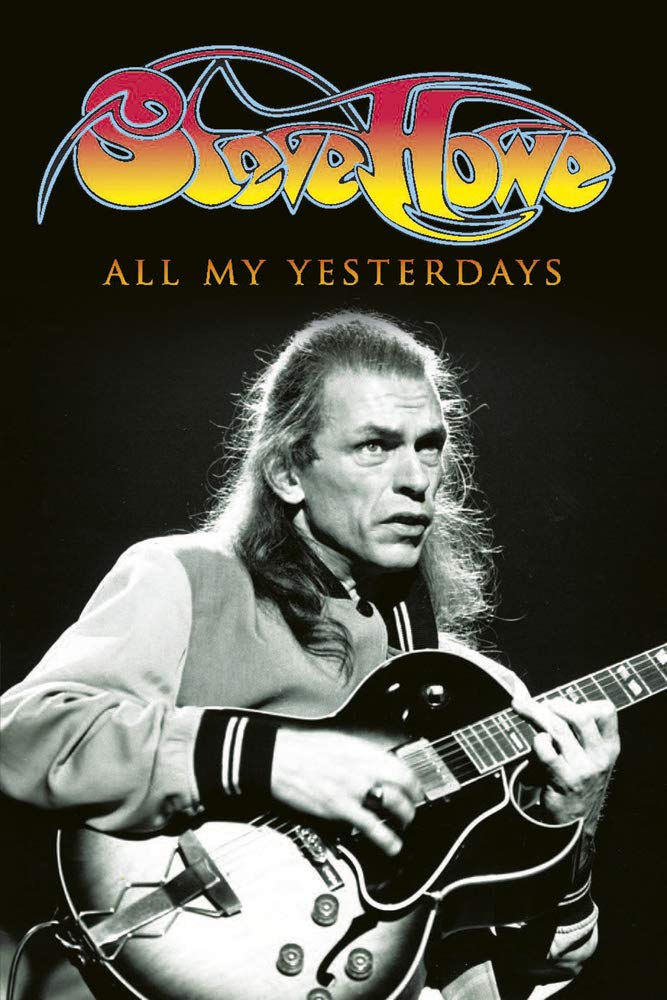

24. All My Yesterdays, by Steve Howe (Omnibus Press). The Yes guitarist’s memoir is thorough, detailing his career from his start in mid-‘60s British R&B bands through the psychedelic group Tomorrow, his peak ‘70s stardom with Yes, and post-Yes work with Asia, GTR, and others, along with his numerous solo projects. Thoroughness doesn’t always mean goodness, and this is the most erratic book on this list. When Howe focuses on how bands evolve and what their music meant to him, and throws in some reasonable human interest stories, there’s some good stuff about not only Yes, but also Tomorrow, the little known Tomorrow-Yes bridge Bodast, and some other acts. There’s a lot of nuts-and-bolts stuff about songwriting, song construction, and recording that might interest readers who are more fanatical about Yes more than they interest me, but that’s fair enough. There are also loads of details about his numerous guitars and associated equipment, and at that point even Yes-heads might get a little lost or uninterested.

It’s to be expected that the story, like so many rock autobiographies and biographies, gets less interesting after the commercial/artistic peak – in this case, after the 1970s Yes years (and, “yes,” their numerous reunions are covered too). But the last half or so of the book gets progressively rote, with whole paragraphs and pages that read like little more than lists of when and where tours took place, interspersed with a few memories of recording sessions and family occasions. Howe does unveil a reasonable sense of humor from time to time, especially when recounting the pitfalls and injustices of the music business. But a strong editorial hand would have really been useful in both condensing the information overload on his less interesting periods, and emphasizing stories and human perspective instead of raw data.

If you like Yes and at least some of Howe’s other work, you’ll find some facts and even insights you’ll appreciate, if much more so in the first half than the second. But even the biggest fans of the guitarist are likely to labor through at least a few of the parts. If you’re wondering whether there’s much dirt on Yes, he restrains himself from throwing much mud around, though it’s obvious he’s had major artistic and personal differences with Jon Anderson, Rick Wakeman, and Chris Squire.

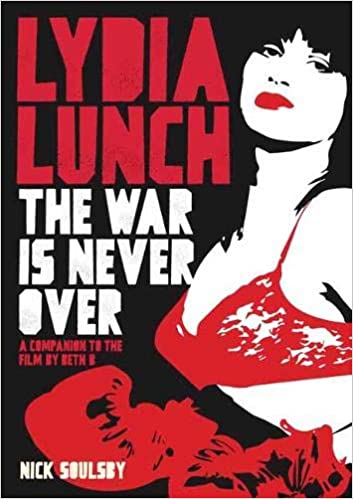

25. Lydia Lunch: The War Is Never Over, by Nick Soulsby (Jawbone Press). Subtitled “a companion to the film by Beth B,” this is likely to be read by a lot of people before they can see the movie, which at this writing seems to have seldom been screened. It’s primarily an oral history of the no wave/punk/goth/all-around subversive singer, with comments from nearly a hundred people who’ve worked with, been intimate with, and/or been influenced by Lunch, as well as some from Lunch herself. Thurston Moore, Exene Cervenka, Beth B, and members of her bands going back to the late ‘70s are among the contributors. If you’re not extremely familiar with her career, you might get a little lost by the procession through her dizzying assortment of projects; while her music gets the most attention, there’s also coverage of her spoken word performances, film appearances, and books. The author helps by providing an introduction and brief links summarizing the activities documented by each chapter, as well as a timeline/filmography/bibliography/discography.

While this is often fairly interesting, the sections on her early work, when she was among the most notorious no wave performers in bands like Teenage Jesus the Jerks, 8-Eyed Spy, and 13.13, are the most valuable. Like many career overviews, it gets less gripping as her activities scatter into numerous other short-lived bands and side projects – though virtually all her bands were short-lived, and she always had many projects going at once. There are plenty of details on her confrontational performances; their reflection of early abuse she suffered, and her use of sexuality as a means of empowerment; and the diligent work ethic she brings to tackling many avenues of expression.

There’s enough repetition of similar praise for her achievements and character that some editing would have been advisable. Some behavior that would be considered gross or nasty by many or most outside of the deep underground is hailed as groundbreaking use of art to combat systemic abuse and oppression. While plenty of people would question that, they’re not the most likely ones to read a book like this. Looking for odd trivia? Here are a couple bits: she played Herman’s Hermits a lot in her early years as a recording artist (and cited “No Milk Today” as a favorite song), and manager Tom Garretson says “we tried to get her signed to Madonna’s label but I think Madonna felt someone like Lydia was threatening to her. I do know the demo wound up on the coffee table at Madonna’s home because a mutual friend saw it there.”

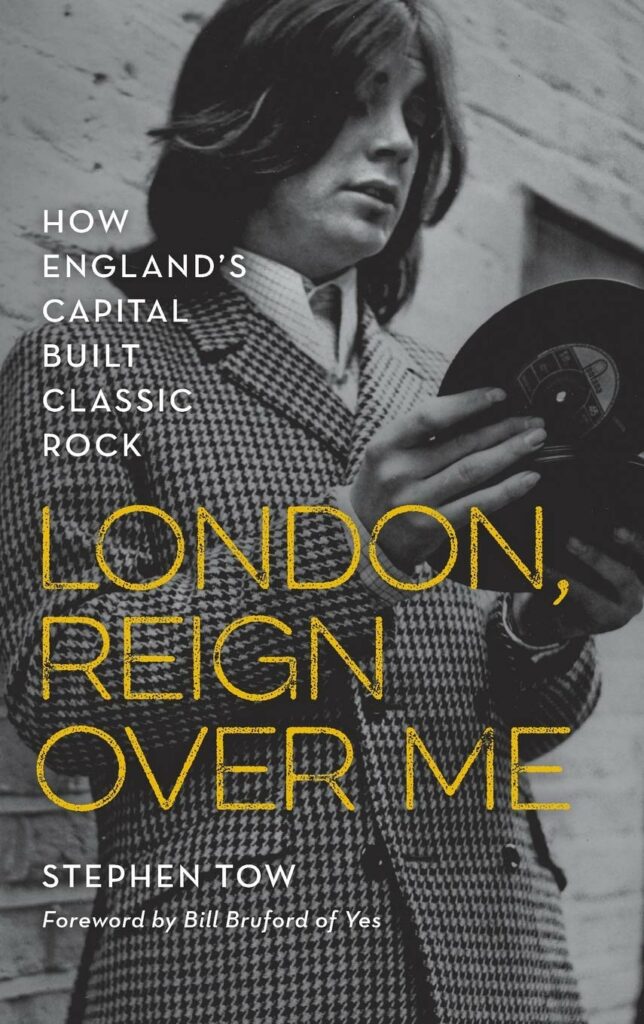

26. London, Reign Over Me: How England’s Capital Built Classic Rock, by Stephen Tow (Rowman & Littlefield). This book’s objective is to detail how London rock of the ‘60s innovated and changed over the course of the decade, from blues and R&B to mod, psychedelia, folk-rock, and progressive rock. It’s okay as a breezy overview of that hugely important scene, though it doesn’t cover every notable act or subgenre, and isn’t long enough to go into any particular artist or aspect in huge depth. I’m a little puzzled as to the aim and value of a not-so-big volume that might serve as a part of an introduction to someone who doesn’t know much about British ‘60s rock. Some acts who didn’t originate in London are covered; the more pop-oriented ones don’t get much coverage, and nor do many women artists; and the focus is often on sweeping summations of their music, rather than the specific London connections. Its main strength are the wealth of quotes—a good many first-hand, and some of the others from obscure period sources—from many of the musicians on the front lines. If you’re pretty familiar with ‘60s British rock, you won’t learn much else.

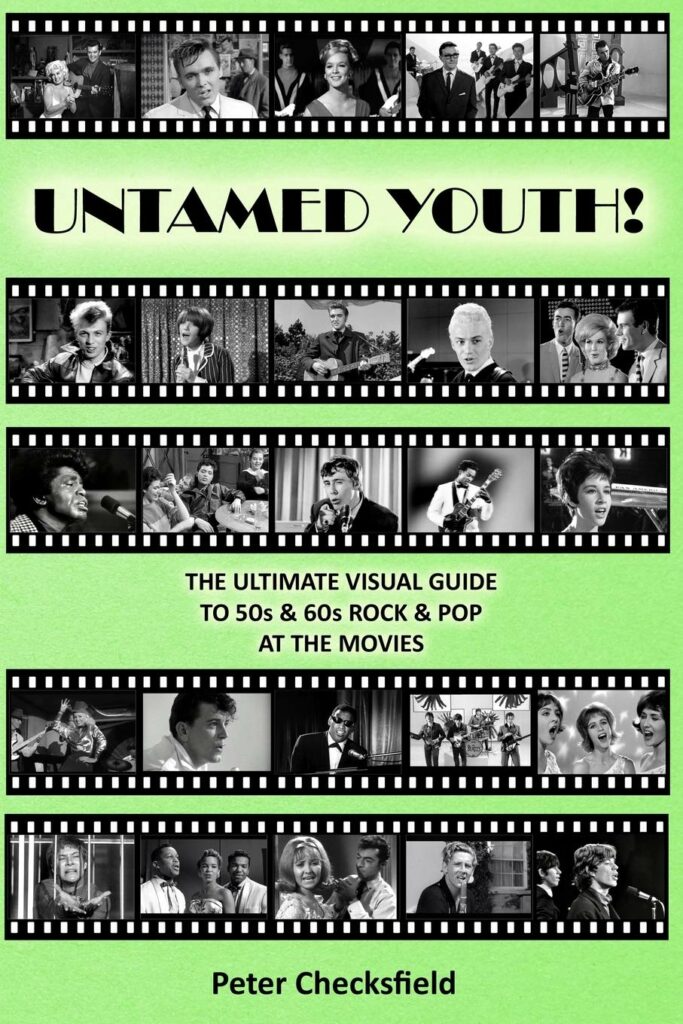

27. Untamed Youth: The Ultimate Visual Guide to 50s & 60s Rock & Pop at the Movies, by Peter Checksfield (peterchecksfield.com). The industrious Peter Checksfield has self-published five music reference books in the last couple years. There’s little text in this one, which is more like an illustrated list of all the pre-1970 musical appearances of rock (and some pop) acts in films that he could find. That means theatrical films (including some shorts), not including TV appearances and promo films, which he’s documented in other books. This isn’t something you’ll sit down and read (or if you do, it won’t take more than an hour or so), as it only notes the title, year, country, and songs performed (whether live or mimed) in each appearance, as well as whether it’s in color or black and white. Each entry has a screenshot of the performer in the film.

This is useful as a reference book, and although the hugely famous items like the Beatles’ films are covered, there are many entries for obscure performers and obscure performances. I’d guess not many fans, for instance, know Amen Corner were in 1969’s Scream and Scream Again, or that the Beau Brummels did “Wait and See” in 1966’s Wild Wild Winter, or that the Zephyrs were actually in a couple movies. Still, it would have been good to have even brief descriptions/critiques of the musical performances/sequences, as Checksfield has offered in other books.

The following books came out in 2019, but I didn’t read them until 2020:

1. How Sweet It Is: A Songwriter’s Reflections on Music, Motown, and the Mystery of the Muse, by Lamont Dozier with Scott B. Bomar (BMG). Dozier was, as is well known, one-third of the Holland-Dozier-Holland songwriting/production team (with brothers Eddie and Brian Holland) that generated many hits for Motown in the mid-1960s. As it happens, the Holland brothers also published a memoir in 2019 (see review farther down the list). Dozier’s book is better, as it’s more straightforward, and more clearly explains how the partnership worked and his role in it—at least, as he sees it. There are also detailed memories of how numerous Motown classics were written, like “Stop! In the Name of Love,” “Heat Wave,” “How Sweet It Is” (which Dozier actually wanted to record himself before being pressured to get a hit for Marvin Gaye), “Reach Out I’ll Be There,” and quite a few others. Some stories aren’t too familiar, like Dozier’s revelation that Supremes vocals were taken off “Baby Don’t You Do It” before Marvin Gaye put his vocal down on the track for a hit. He didn’t really have to do it, but Dozier also puts paragraphs in which he highlights points/suggestions about songwriting in bold.

That’s the heart of the book, but there’s also a fair amount about how he and the Hollands continued their partnership at the Hot Wax/Invictus labels in the late 1960s and early 1970s, though that didn’t end well as they went in different business and musical directions. The complicated circumstances leading to their acrimonious departure from Motown are still complicated as relayed here, but at least they’re less oblique and more concrete than they are when depicted in the Hollands’ book. The text steadily declines in interest as it shifts to Dozier’s solo recording career in the ‘70s and ‘80s, and his periodic successes with different partners to the present day. In common with many a musical memoir, there’s a little too much in the way of childhood memories too. But the most interesting passages of Dozier’s life and career take appropriate precedence, and it’s a worthwhile entry in the volumes of books about or by Motown figureheads.

2. Echoes, by Glenn Phillips (Snow Star Publishing). Subtitled “The Hampton Grease Band, My Life, My Music and How I Stopped Having Panic Attacks,” Phillips’s memoir covers one of the longest-lived cult rock careers. The Atlanta guitarist’s discography spans half a century, from his barely-out-of-his-teens stint with the Hampton Grease Band in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s through many solo albums. He’s been on Virgin Records, SST Records, and Columbia, as well as putting out his own discs. Through it all, he’s never been too close to the mainstream. The Hampton Grease Band’s sole album (a double LP) wasn’t just goofy avant-rock, but also allegedly one of the lowest-selling records in Columbia’s history. His solo projects have gotten their share of critical acclaim, but have never sold in great numbers or been too commercial.

In itself that makes for an interesting story. But for a rock memoir, Echoes has an uncommonly good balance between musical and personal experiences, with a concise focus missing from many rock autobiographies. His personal life could be harrowing, including alcoholic parents, stormy affairs with unstable women, and the suicide of his father, committed on the father’s fiftieth birthday. As a musician, he’s run the gamut from recording for a young Richard Branson to gluing together his own self-pressed LPs—and those experiences took place pretty close to each other. If you’re especially interested in the Hampton Grease Band’s career, that takes up a good third or so of the book, a section funny for its coverage of their stranger-than-fiction shows and recording decisions. It’s also sad for the portraits of eccentrically impossible-to-deal-with lead singer Bruce Hampton (who blocked release of archival live recordings through his obstreperousness) and guitarist Harold Kelling (who died after a long descent into alcoholism). Phillips maintains a level-headed mix of humor and serious self-examination, with an entertaining knack for retelling a stack of improbable anecdotes.

3. Good Lovin’: My Life As a Rascal, by Gene Cornish with Stephen Miller (genecornish.com). Of all the items on this list, this is the one that flew the most under the radar, attracting no reviews or even online comments that I saw. Cornish was guitarist in the Rascals, and the least well known of the four. Still, he’s the only one of the still-surviving quartet to have written a memoir. This 530-page book covers his whole career, and isn’t as lengthy a read as that figure might indicate, since the print is large and the margins are wide.

There’s a lot of detail in this autobiography, from his days in scuffling pre-Rascals bands in Rochester, New York through the half-dozen years or so he was in the Rascals, his obscure post-Rascals groups, and their reunions. The style is fairly informal and anecdotal, and has neat nuggets like how Atlantic Records recorded the group live to get a feel for how they should sound in the studio prior to their first LP (does that tape still exist?); why they turned down a chance to record with Phil Spector; Atlantic’s unwillingness to issue “Groovin’” and “People Got to Be Free” as singles, thinking they were too risky and too much of a departure from their sound; and the other Rascals’ initial fury at Cornish for approving the version of “Good Lovin’” that became their first huge hit.

There’s also a lot of love and criticism of his fellow Rascals – not so much drummer Dino Danelli, but certainly Felix Cavaliere, which didn’t stop Cavaliere from writing a kind introduction. Singer Eddie Brigati also comes in for his share of knocks for leaving the group and not committing to some reunions, though Cornish can also be tough on himself, acknowledging his decades-long descent into drug abuse after his time in the Rascals ended.

Cornish’s post-Rascals decades were rough indeed, finding him at times scrounging for food and a roof over his head. The last third or so of the book is largely devoted to those struggles and his continual Rascals reunions or semi-reunions, and can make for a drawn-out downer, though many rock memoirs follow that path. And like many other rock memoirs, this has some mistakes in rock history chronology that numerous knowledgeable readers (not just Rascals fanatics) will spot, along with a good number of typos that could have been more carefully checked. However, overall these are minor gremlins in a pretty comprehensive overview that any Rascals fan will be interested to read.

4. Come and Get These Memories: The Genius of Holland-Dozier-Holland Motown’s Incomparable Songwriters, by Eddie and Brian Holland with Dave Thompson (Omnibus). The Hollands were two-thirds of the songwriting/production team responsible for more Motown hits than any other, especially for the Supremes, Four Tops, and Martha & the Vandellas. This is more oral history than standard memoir, with extensive quotes from both brothers linked by some narrative text written in their dual voice. The bulk of this appropriately focuses on their early-to-mid-‘60s work for Motown, though their activities at the label where they subsequently worked, Invictus, are also covered. There’s a good share of interesting stories about the writing of many of their famous songs, the division of their production/composing duties, and the inner machinery of the Motown operation.

It’s not quite the knockout book for which some Motown/soul fans might be hoping. There’s too much time spent on their family upbringing, and Dozier’s role, while not neglected, certainly gets a lot less space than the Hollands’. He didn’t participate in this project, which might have something to do with some business and creative disputes they’ve had, though these took place after Motown. The trio’s split from Motown in the late ‘60s—a move that neither the trio nor the label never fully recovered from—gets a few pages, but is described in roundabout terms that make it difficult to determine exactly what was being disputed. It does seem like Eddie was the main man from the trio negotiating with Berry Gordy, and though he says “it could have been solved with one phone call,” it didn’t help that he didn’t read his lawyer’s 32-page response to one crucial round until years later. More revelatory are Brian’s recollections of a mid-‘60s relationship with Diana Ross, and how that affected what he was writing for the Supremes.

5. Some People Are Crazy: The John Martyn Story, by John Neil Munro (Polygon). Martyn is one of those guys whose records I never find as interesting to listen to as reviews of them lead me to expect. He’s also one of those guys whose story interests me more than his music, in part because he was part of a British folk-rock scene that’s a big interest of mine, though I don’t like him nearly as much as Nick Drake, Donovan, or Sandy Denny, to name just a few of his peers. This is a reasonably interesting bio of the folk-rock (with a lot of jazz, some blues, some reggae, and some electronic experimentation) singer-songwriter-guitarist, originally published in 2007, and revised/updated in 2019. It follows his career from his Scottish youth through his early albums (some with first wife Beverley Martyn), his peak of critical acclaim with early-to-mid-‘70s albums, his increasingly fitful post-‘70s work, and his death in 2009 after massive health problems (including an amputated leg and obesity). Plenty of people who knew and worked with him were interviewed, along with Martyn himself.

Tellingly, a few figures who worked with him extremely closely did not speak about Martyn, whose volatile personality put plenty of colleagues off. Most notable among the absentees are Joe Boyd, who produced early Martyn records and found him distasteful to work with; Chris Blackwell, who as head of Island Records gave Martyn the chance to record many albums, though the singer was never a big seller; and Beverley Martyn, who had a rocky marriage with John, and felt he curtailed her own musical career (though the author contests whether this was definitely the case). There’s plenty of info about his recordings and his prickly persona, and friendships with Nick Drake and Paul Kossoff (both of whom died tragically young), though occasionally the text rambles and doesn’t fully fill in some gaps in his arc. His alcoholism and rough treatment of some of his romantic partners are not overlooked, though criticism of his flaws is a little restrained, and his diverse musical talents enthusiastically celebrated. It leaves the impression that many of us would go out of our way to avoid this mercurial man who was capable of great nastiness, as documented in Beverley Martyn’s memoir.

6. Me, by Elton John (Henry Holt). I’m not a big Elton John fan, which explains why it took me more than a year to get around to checking out a memoir by a major rock star whose career started in the late ‘60s out of the library. Still, I acknowledge this is a pretty interesting, well-written autobiography. He has a good British self-deprecating sense of humor about himself and the frequent absurdities of the music business, going all the way back to his days as a backup pianist for Long John Baldry in Bluesology. He’s unapologetic about his love for some aspects of celebrity excess, like shopping sprees and camp clothing. That’s balanced, somewhat, by detailed recounts of his drug and relationship problems, and his contributions to numerous charitable causes.

If you’re more interested in his pre-late-‘70s work—the part that’s gained him by far the most critical respect—than anything else, know that this covers all phases of his career fairly evenly, the post-mid-‘70s eras taking up more than half the book. As for whether this follows the common trail of rise to success followed by cocaine addition, rehab, fallow artistic periods, hobnobbing with non-musical celebrities, and redemption of sorts through family love, this book’s not an exception. If you’re a record nerd who wants details about his early tours and albums, there are a fair amount of those, though some well known songs are barely or not discussed. His long personal/professional association with lyricist Bernie Taupin is covered in depth, however, and most readers with a casual or greater interest in Elton John will find at least some sections worth reading, even if you skim some of the rest.

7. The Beatles: Tell Me What You See, by Peter Checksfield (peterchecksfield.com). Subtitled “the ultimate guide to John Paul George & Ringo on TV and video,” this lists all known footage of musical performances (live and mimed) by the Beatles, both as a group and solo performers. It follows the same format as his two previous useful reference books, Channeling the Beat! (for UK ‘60s pop on TV) and Look Wot They Dun! (for UK glam rock on TV). All dates, sources, and locations (when known) are listed, along with brief descriptions, as well as notes as to whether the footage survives. It’s a handy primer for what you can view, including promo and feature films as well as TV appearances. Note that the solo years take up a much larger part of the book—about 200 of its 280 pages—than the section devoted to the Beatles as a group. In fact, Paul McCartney’s section alone takes up a little more than a hundred pages. Through no fault of the author, that means some parts—namely the later solo years—are a lot less interesting than others, namely the Beatles and the early solo films.

8. The Last Four Years, by Annette Walter-Lax in conversation with Spencer Brown (self-published). Walter-Lax was Keith Moon’s girlfriend the last four years of his life, and with him when he died in his sleep in September 1978. This isn’t a conventional memoir, although it recounts their time together in detail. The first part, taking up almost the first half of the 200-page book, has quotes from recent interviews Spencer Brown did with her, linked by Brown’s narrative text. The rest of the book offers Q&As from the interviews covering various topics, like their trips abroad and particularly troublesome incidents in which Moon destroyed hotel rooms or caused general havoc. There was a lot of that when you were around Moon, maybe more so in his final years than during his first decade with the Who. In his case, it was yet more excessive than most downward booze-and-drug-fueled spirals. In common with many another celebrity memoir, it becomes evident he isn’t going to get his act together. It also becomes evident that his partner, for whatever reasons, won’t leave him in spite of his abusive behavior – not physical abuse, but having sex with another woman in front of you certainly qualifies among the worst forms of abuse.

This is a quicker read than its 200-page length might set your gears for, as there are pages with a lot of white space, and sections of black-and-white photos from their relationship (reproduced in mediocre quality). There’s also a fair amount of repetition of similar sentiments and overlap between what’s covered in the first part and the Q&As. The point is made, in fairly interesting but depression fashion, that if anything Moon’s descent was worse than has usually been reported, and he might well have died earlier from his recklessness. It also notes that his physical and mental problems were affecting his musicianship, and that the couple’s extended stay in Hollywood (in which Moon hoped to enter films, and recorded a poor solo album) was pretty disastrous both in terms of professional self-sabotage and the burning of bridges even with fellow hard-partying rock buddies.