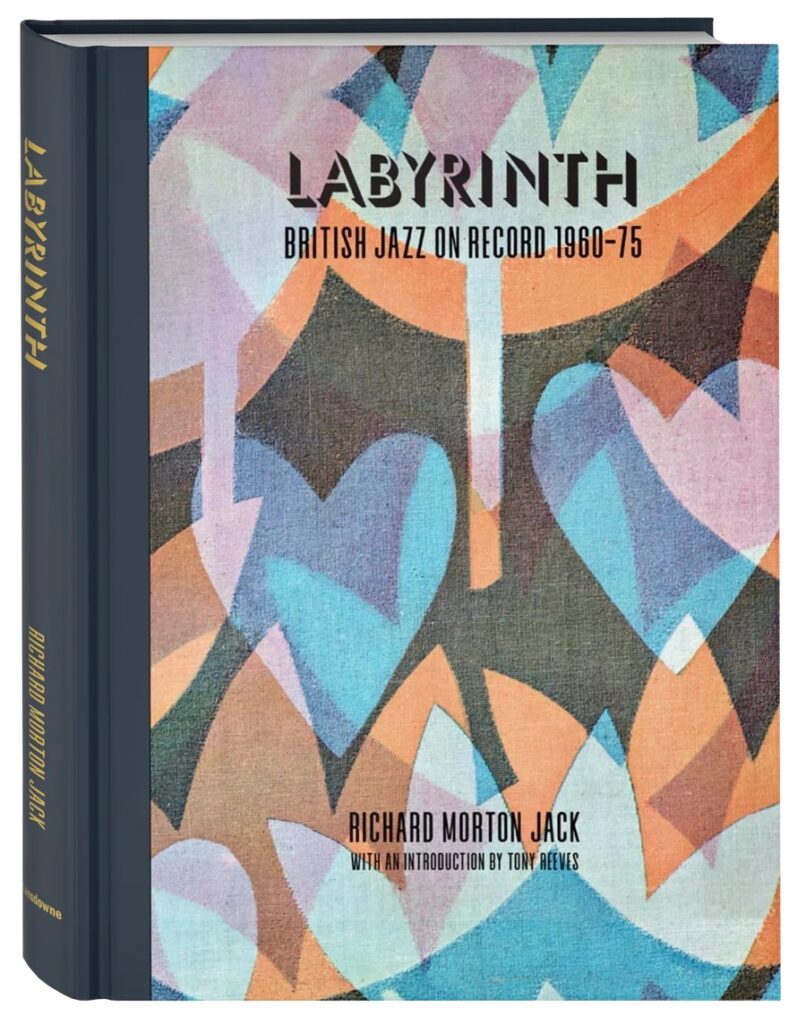

British jazz from the 1960s and first half of the 1970s isn’t, dare I say, a specialty of too many people, even in the UK, and less so elsewhere. However, Richard Morton Jack’s limited edition hardback book Labyrinth: British Jazz on Record 1960-75—published earlier this year on Landsdowne—is an exceptionally well produced record guide to many of the British jazz LPs made between 1960 and 1975. Morton Jack has issued a couple other hefty compendiums of reviews/descriptions of both British and North American rock records of the period, Galactic Ramble (covering the British Isles) and Endless Trip (covering North America). Although a few folk and jazz albums are documented in Galactic Ramble, Labyrinth is exclusively devoted to British jazz, allowed for far more coverage of the genre.

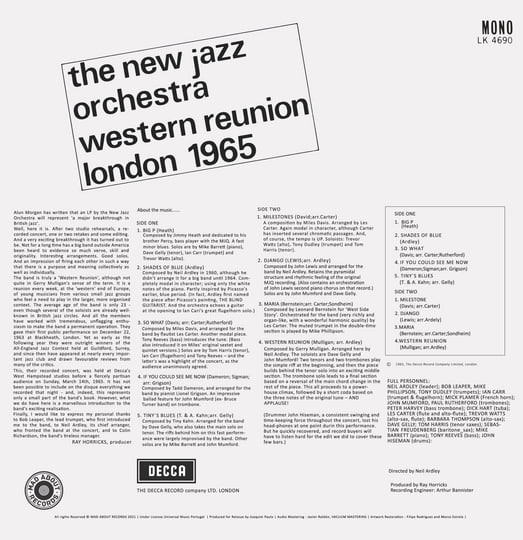

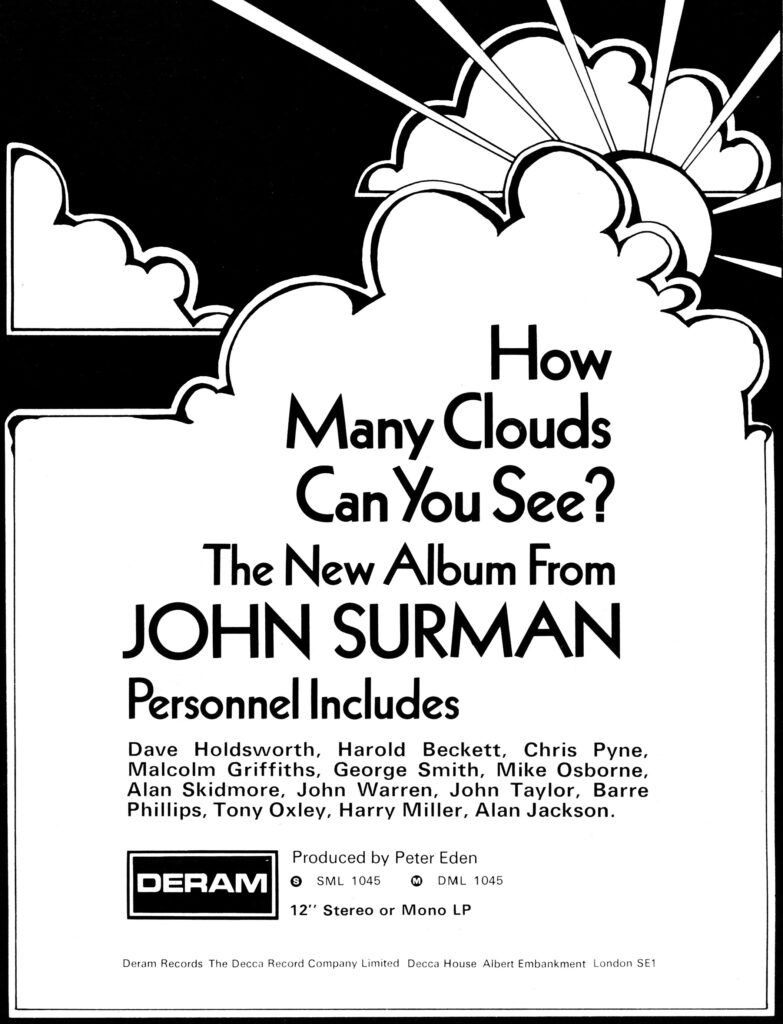

Labyrinth isn’t just a discography listing catalog numbers and dates. Each of the several hundred albums gets a fully considered paragraph-long description by the author. Many of the entries also include excerpts from reviews of the albums actually printed around the time of their release, along with full-page reproductions of the front and back covers and inner labels. There’s also a very interesting and lengthy introduction by musician and producer Tony Reeves, who was part of and worked with several acts during this period, most famously Colosseum. Plus there are also a few pages reproducing ads of the time for British jazz releases.

Even within the world of jazz enthusiasts and collectors, British jazz doesn’t get a ton of attention, and many of the names will be unfamiliar to readers as few made an international impact. The ones that did tended to be ones whose impact bled over to the rock audience, like Jack Bruce, John McLaughlin, Chris Spedding, Colosseum (though only their first LP is included), Harold McNair (via his work with Donovan), John Cameron (also as a Donovan associate), Hugh Hopper (with Soft Machine), Elton Dean (part of Soft Machine for a while), Henry Lowther (part of Manfred Mann and John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers for a while), and others. Morton Jack covered some British rock with a jazz influence in Galactic Ramble, and rock albums by the many acts with players with jazz experience are usually detailed in there.

This is the place to learn about names known more to jazz aficionados, like Joe Harriott, Mike Westbrook, Norma Winstone, Michael Gibbs, and Nucleus, though one (Dudley Moore) is extremely famous, though not principally for his accomplished jazz piano. It also offers insight into some styles that were more prevalent in British jazz than elsewhere, like Indo-Jazz. The quality of the writing is extremely high, as is the quality of the writing and graphics—a relative rarity among such specialist guides.

Richard Morton Jack is also the author of the superb and very highly regarded 2023 biography Nick Drake: The Life, which I interviewed him about last year on this blog. I also interviewed him about Galactic Ramble in a previous blogpost. He graciously answered my twenty questions about Labyrinth in June 2024, a few months after its publication.

You’ve edited, published, and written much of your previous guides focusing on rock LPs from the early 1960s to the mid-1970s, with different books for the North American and British Isles scenes. Some jazz LPs were covered in your Galactic Ramble book, which mostly focused on British Isles rock LPs from the era, with some folk as well. But Labyrinth focuses exclusively on British jazz LPs from 1960-1975. What made you decide to do an entire book on the subject?

Whilst pop, rock, psychedelia, prog, folk, and other genres of that era been extensively revisited and explored, British jazz has been relatively neglected. Pulling together a detailed, heavily illustrated guide to it struck me as a worthwhile way both to commemorate it and stimulate interest in it. Also, because not much jazz was in fact released in Britain in this period, I was able to include almost all of it (with the notable exception of trad).

Labyrinth‘s format is different from Endless Trip and Galactic Ramble, although there are some similarities. Like your other books, Labyrinth prints excerpts of many reviews of the LPs actually written at the time, alongside recently written reviews composed specifically for the volume. However, where the other books had recently written reviews by several writers, you wrote all of the several hundred or so reviews in Labyrinth, though Tony Reeves wrote a detailed foreword. Every single one of the albums detailed in Labyrinth has a newly written review, though in your other volumes, some entries only had excerpts from period reviews. Also, while the other volumes had many illustrations of record covers and reprints of advertisements, Labyrinth has large full-page reprints of many (though not all) of the LPs’ front and back covers, as well as reproductions of the inner labels. What made you decide to go this route for the format and design?

I hesitate over the word ‘review’ to describe my text in Labyrinth – I intended my entries on each album to be historical or factual rather than critical, and therefore tried to leave my own opinions out of them.

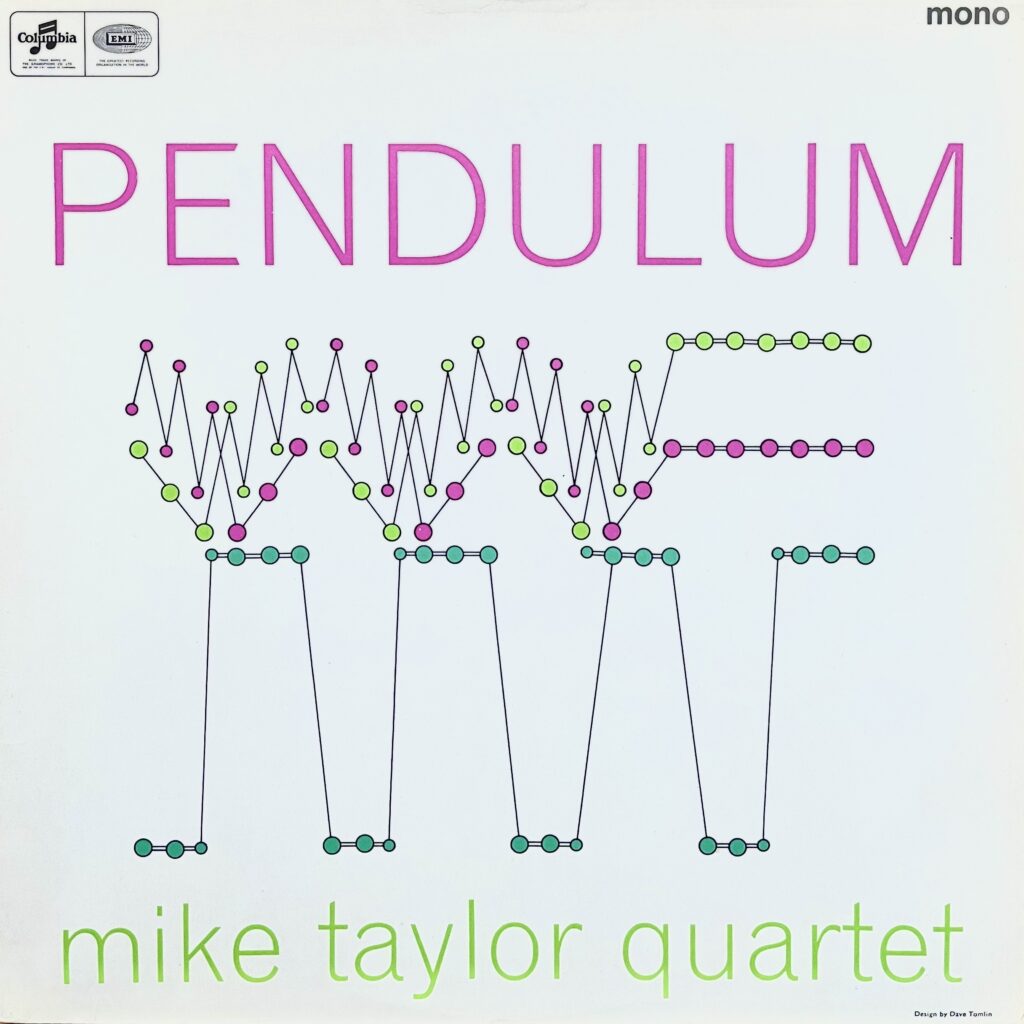

I felt that reproducing their artwork at near-enough full size was worthwhile on aesthetic grounds, and – more importantly – that the small print on many of their back covers is of great interest, yet because so many of the albums are rare, most people will never get to read them. One example out of my head: virtually the only immediate information regarding Mike Taylor’s music is buried on the back cover of his LPs. Therefore, a large part of the intention of Labyrinth was to reproduce sleevenotes legibly.

While as noted many of the albums get the full design treatment of large repros of the front/back covers and inner labels, as well as quotes from period reviews, some of them only get your paragraph-long review and a much smaller reprint of the front cover. While I thought maybe the less essential LPs were chosen for this briefer treatment, some of them get very good reviews by you. Were the ones given less space chosen because there weren’t good vintage review quotes; because the covers weren’t visually interesting; or for some other reasons?

In some cases I didn’t think the albums were of sufficient interest (whether in terms of music or artwork or both) to merit two-page spreads. In some cases I could find no original reviews, meaning that the text accompanying the artwork would’ve been skimpy. And I tended to relegate the few albums that had gatefolds to shared spreads, because reproducing their artwork in full would have involved shrinking them, thereby defeating the object.

There’s a wealth of excerpt quotes from reviews of albums when or shortly after they appeared. Some of them are from music publications with wide circulations and/or a jazz focus such as Melody Maker and Down Beat, but many are from far more obscure sources like local British general interest papers in cities like Bristol and Newcastle, and long unavailable little-known publications like Amateur Tape Recording. I know you have a huge collection of periodicals, but was this a matter of going through what you had, searching for additional reviews as part of your specific research for this book, or a combination of the two?

It was a case of combing through as many publications as I possibly could, in search of insightful or revealing information from the time of each album’s release. Although contemporary reviews were often written hastily, and with strong personal bias, I feel strongly that the dual perspective is enlightening: understanding how albums were received upon first release gives a sense of immediacy and perspective that revisionist reviews can’t match, even if we might well feel that their evaluations are wrong-headed.

Along those lines, were there any unlikely review sources that particularly startled you, a la the Bert Jansch and Nick Drake reviews you’ve previously found in Penthouse?

Funnily enough, Penthouse had decent jazz coverage too – for example, they ran a piece about Neil Ardley and the New Jazz Orchestra in an early 1965 issue, well before they had an album out. Leaving aside pornography, national press coverage of jazz was wider and more earnest than of pop and rock, even though it was clearly of far less popular interest: the notion of taking pop music and musicians seriously was more or less alien to mainstream journalism in that era. And it’s always fun to read Philip Larkin’s ornery Telegraph reviews (by no means all of which have been anthologised).

What really startles me about all British musical coverage of the 1960s and early 1970s is the sheer volume of it. Every week brought a new issue of Melody Maker, Disc, Record Mirror, Music Echo, Sounds, Top Pops, Music Now, the NMEand others, which had very broad remits. That’s not to mention the underground press and specialist monthly magazines (including jazz titles such as Jazzbeat, Crescendo, Jazz Monthly, Jazz & Blues and so on). A huge amount of valuable information is buried in them all.

Turning more to the content rather than the record guide-like format, British jazz hasn’t often gotten this serious critical approach in book form, written with intelligent perspective, yet also meant to be accessible to the collector and general listener. What do you think were the chief qualities that made British jazz most distinctive in this period, and specifically, distinct from the North American (and sometimes European) jazz that got a much bigger audience and much more attention from the music industry and critics?

I’m hesitant to ascribe musical qualities to British jazz that weren’t present in European or North American jazz, and can’t swear that I could identify a 60s jazz recording as being British rather than (say) Swedish. What I will suggest is that the British scene was more insular, for various reasons. That insularity led the musicians to get to know each other pretty well over the years, and to develop empathy and rapport for each other’s personal styles that creates threads between disparate recordings.

There was also an extraordinarily enlightened attitude within the British record industry at the time, which permitted these commercially kamikaze records to be written, recorded and released. As I say in my introduction to the book, but for a genuinely small number of executives, virtually none of the music in the book would ever have been recorded.

As a related question, do you feel there were notable sub-genres or styles distinct to British jazz?

Again, I’m hesitant to make great claims for anything unique about British jazz, but I do think that individuals with strong ideas were encouraged to develop them and present them free of commercial considerations in a way that ceased to be possible as of circa 1973. Visionaries like Mike Taylor, Neil Ardley, Graham Collier and others were therefore able to develop their own distinctive approaches free of (much) interference or outside pressure, musically at least. The Arts Council (funded by the government) also made grants to numerous jazz composers in this era, which allowed them to work free of financial pressure – for short periods, anyway.

And as a related question to that, one that seems more prevalent in British jazz than elsewhere was what’s called Indo-jazz. There seems like a specific reason for that, Indian residents and culture being a pretty big part of British life and a much bigger one than in North America, owing to India having been a British colony. Would you agree with this, and what do you think were the most outstanding qualities of this branch of British jazz?

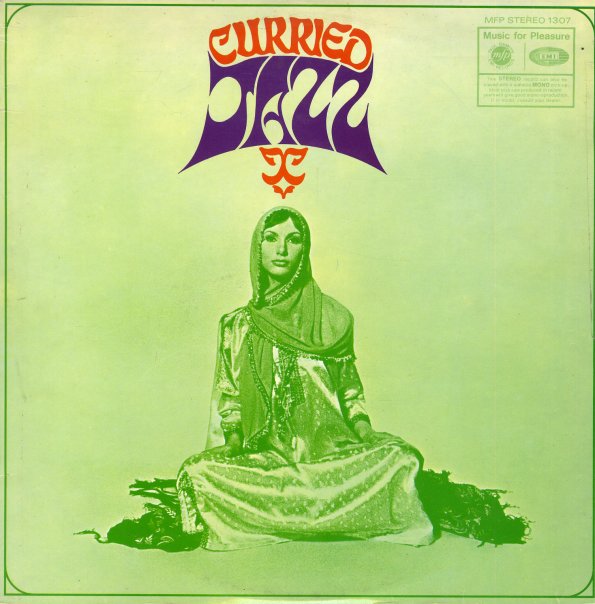

Denis Preston, the remarkable proprietor of Lansdowne Studios and architect of the so-called ‘Lansdowne Series’ – an EMI brand that essentially consisted of whatever he wanted to release – took a strong interest in what we now call ‘world music’. Rather than making ‘field’ recordings, his approach was to get excellent expat or visiting musicians to make studio recordings that typified aspects of the music of their home countries. He admired the Indian composer John Mayer and the Jamaican saxophonist Joe Harriott, and therefore suggested in 1965 that they bring their respective groups together. I personally find the results a little awkward, enjoyable though they are, and think the best venture in that style is the flippantly named Curried Jazz (which came out on a budget label in 1968, credited to the Indo-British Ensemble).

On a slightly different tack, the first album by the Goan guitarist Amanda D’Silva doesn’t attempt to fuse sitars and other Indian instruments with jazz, but gives him the space to reflect India’s musical heritage through the electric guitar, with standard jazz backing. I think that makes for a more original and striking result.

As you note in a number of the reviews, it’s astonishing what uncommercial and experimental jazz albums found release on some major labels during this period. A good example is one I happen to have (as a CD reissue, not the original LP), Hugh Hopper’s 1984, which you wrote ‘has to be about as uncommercial an album as was ever released by a major label’. How do you account for the presence of these sort of records on majors at the time, other than perhaps the general assumption that they were throwing all kinds of things at the wall to see what stuck?

I think that would be cynical in the case of jazz. The great Hugh Mendl, one of the most senior executives at Decca in the 1960s, told me shortly before his death that he had always passionately believed that major record companies had a cultural duty to preserve for posterity music that was of value, even if it had dismal commercial prospects. In other words, the vast profits being generated by the likes of the Beatles and the Stones should partly be used to underwrite the work of equally valid but less financially rewarding artists.

Hugh wasn’t alone in this: David Howells, a senior executive at CBS in London in this period, was passionate about avant-garde jazz and produced records by Tony Oxley and other utterly uncommercial musicians, yet had (and still has) genuinely equal respect and enthusiasm for the Love Affair, the Marmalade, the Tremeloes and other pop acts he was involved with. It didn’t seem at all contradictory to him to like and encourage both. That broadminded attitude pervaded the British music industry in that era: if something was good of its sort, it was regarded as worthy of support. I also think that it was a short and wondrous period in which there was a respectable market for challenging music. Captain Beefheart’s Trout Mask Replica was a hit in the UK! I recently saw the official CBS sales report to the end of 1969: its British release was in mid-November, and in its first six weeks it sold 9296 copies. That’s really remarkable, especially when you consider it was an expensive double LP.

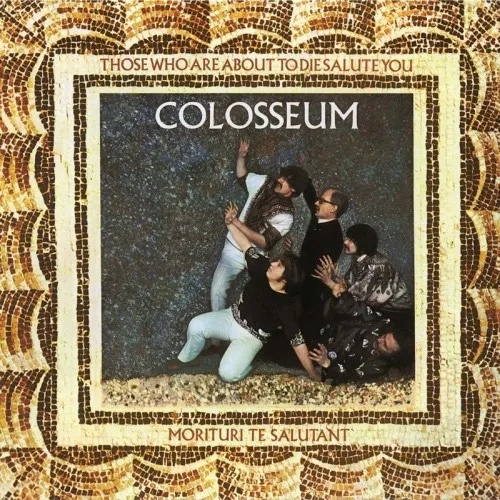

As you explain in your introduction, you drew the line at including much jazz-rock that was at least or more rock than jazz—Soft Machine might be a good example—I think in part because much such product was reviewed in Galactic Ramble. However, you did include Colosseum’s first album in Labyrinth. While personally I’m glad you did since I like that record, it seems like an exception to an informal rule, as it owes a lot to blues-rock, perhaps more than it does to jazz. Was there a specific reason you thought this qualified for inclusion?

I didn’t leave anything out of Labyrinth on the grounds that I’d covered it elsewhere. I approached the book entirely as an entity unto itself. I can’t defend the omission of, say, the Soft Machine other than by saying that they seemed to me to tilt further towards the ‘rock’ than ‘jazz’ part of ‘jazz-rock’, and that by including them I would have been opening the door to other jazzy rock records (by, say, Web, Brainchild, Skin Alley, Heaven and Iguana) that would have bloated the book and blurred its focus.

From my perspective, Colosseum are of specific interest because Jon Hiseman and Tony Reeves had come from a jazz background and were seeking not only to broaden their repertoire but to bring music that had been regarded as fairly obscure into a more mainstream market. That’s why they used the line ‘morituri te salutant’ for their album title: they did feel a sense of jeopardy in bringing jazz to rock audiences in the UK.

Many notable British rock musicians of the period had some background in jazz, and sometimes even made jazz or certainly heavily jazz-influenced records, though they’re mostly known for the rock or jazz-rock they did. As I know you’re aware, the list is long and goes all the way up to Brian Jones and Charlie Watts in the Rolling Stones, also including Graham Bond (though the album he did as part of Don Rendell’s group is covered), Jack Bruce, Ginger Baker, Dick Heckstall-Smith, Robert Wyatt, Manfred Mann (both the leader and some members of his group), Brian Auger, Georgie Fame, members of Pentangle, Duffy Power, some of the Bluesbreakers, John McLaughlin, Van Morrison…the list could go on. Is this branch of British jazz, or at least music that owes a lot to jazz, one that you’re tempted to write about in the future, or think someone could? (I’m aware there were a few items by or associated with some of these names in Labyrinth, including solo LPs by Bruce, McLaughlin, and Hugh Hopper, and the Watts-assisted People Band LP.)

I suspect trying to unpick the incredibly broad range of influences and attitudes that came together in British popular music in the 1960s is a fool’s errand. What’s salutary for me is how versatile and well-schooled so many musicians were, including everyone you’ve named. I’m not convinced that mainstream popular music will ever again be dominated by individuals with such diverse musical backgrounds and skills, and such catholic tastes.

And another related question: there weren’t anything like the parade of jazz players moving effectively into top ranks of rock in North America as there was in the British Isles. Conversely, there weren’t anything like the parade of folk musicians moving into the top ranks of rock in the British Isles as there was in North America, Donovan being a notable exception. Do you, like me, see a similarity in those movements, in that jazz might have helped bring a more cerebral and sophisticated strain into rock in the British Isles, just as folk did in North America when many folkies went electric?

I think it’s a perfectly valid line of thought. Perhaps it’s also worth considering whether the relative number of regional clubs made it easier to scratch a living out of jazz in America than in Britain, and easier to scratch a living out of folk in Britain than in America.

Separately, Miles Davis was able to reach a broad rock audience in America in the late 60s in a way that’s hard to envisage for a British player. I think that’s partly because Britain was a much smaller market, so it was easier to sell Miles’s fusion records into the UK than to focus on breaking, say, Ray Russell (not that I’m comparing their talent or commercial prospects) internationally. It’s perhaps instructive that John McLaughlin felt the need to move to America to communicate his music in the way he thought necessary.

It’s also worth noting that the vast majority of jazz coverage in Britain was for American jazz, reflecting a general sense that British jazz was somehow ersatz. That gradually eased off, but I suspect a lot of British players felt a little aggrieved or defensive as a result.

Getting back to straight British jazz: North American jazz musicians, and some European musicians like Stephane Grappelli and Gabor Szabo, got a much bigger international audience (including in the UK) than British jazz musicians did outside of the British Isles. There are a few here and there that have a few cult followers in North America, like Derek Bailey and Keith Tippett, but not many. Indeed, most British jazz of the time is still unknown or virtually unknown here, even among many jazz aficionados. To what do you attribute this, from both musical and business/promotional perspectives?

To be fair, Decca (for instance) did release a reasonable number of British jazz records in America through its London affiliate, so Mike Westbrook, John Surman, Michael Gibbs and others did at least have some of their records issued there. But clearly records that had barely sold in the UK were never going to be of much interest to foreign licensors, and it was always easier for large international record companies to market major US jazz artists (and I would include Szabo as American in this context) internationally than to attempt to break a large number of new local names in smaller territories. I don’t think there’s any valid musical grounds for it: British jazz has simply taken a very long time to filter through.

As an aside, it’s intriguing that Japan was the biggest foreign market for British jazz back in the day, with numerous obscure and challenging albums coming out over there, often with revised artwork and detailed insights giving background information that even the British releases lacked. And the market for original pressings of British records has always been livelier in Japan than anywhere else.

Even collectors who aren’t interested in this kind of music might be interested in this book because of the graphics on the album covers. Many of them are striking, and even the ones that aren’t so good—and you sometimes point out ones with substandard or even laughable covers in your reviews—hold some fascination for their period qualities, making them look either unique to their time or reflective of the general music business values of the era. They’re too diverse to put into one or two categories, but what do you think generally were some of the most interesting qualities of the British jazz LP graphics of the period, and ones that made them distinct not only from other periods, but also from the graphics used on LP covers of other genres in 1960-75?

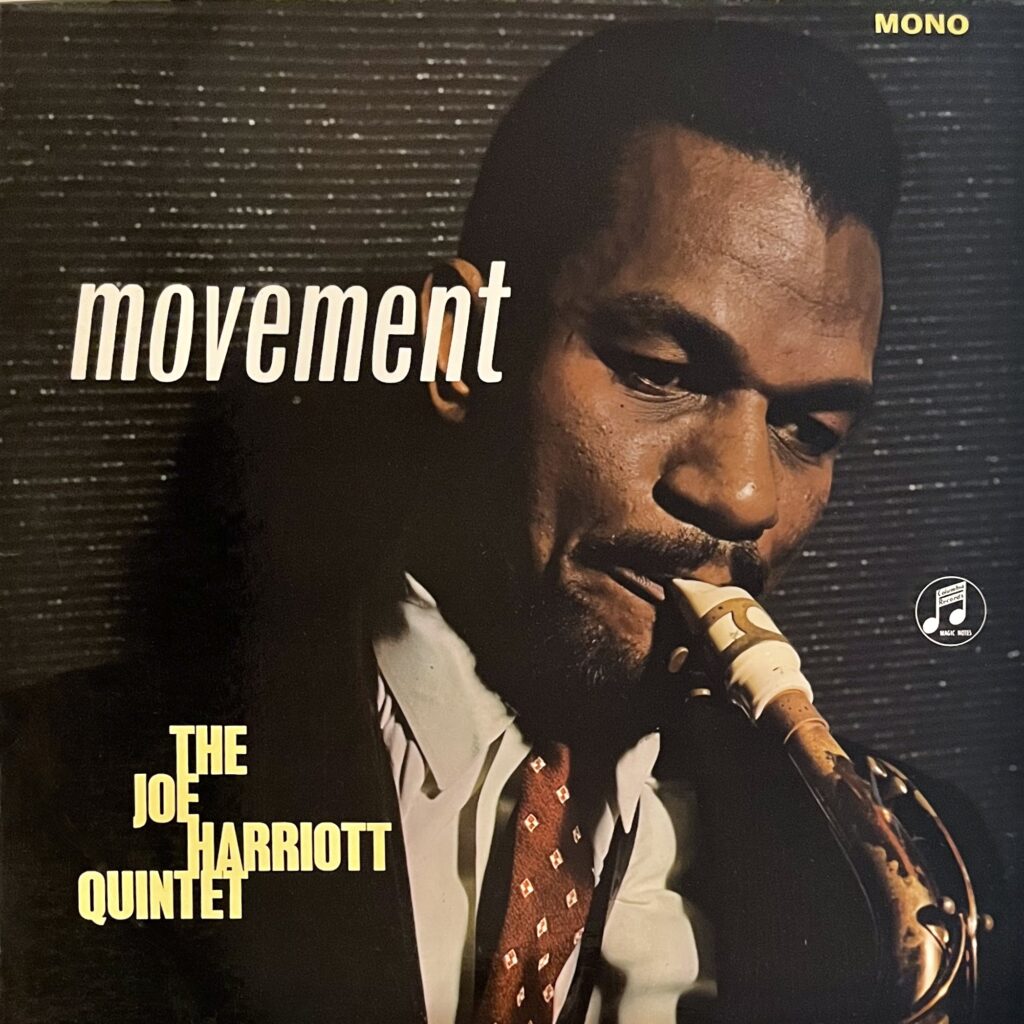

With reference to the early 60s – in other words, the beginning of the period covered by the book – perhaps there’s an argument that jazz fans tended to be older and more aesthetically sophisticated and discerning than pop fans, and therefore expected more interesting imagery when buying an LP. That said, the covers of Down In The Village by Tubby Hayes and Movement by Joe Harriott (to give two examples) feature close-ups of their faces in the manner of a Cliff Richard or Frank Ifield album.

As the decade progresses, I’m not sure I can distinguish between graphics on jazz records and pop or rock records. I think the movement away from straightforward photographs and towards more abstract or imaginative concepts happened in parallel for rock and jazz, and that by the turn of the decade a lot of their designs were interchangeable. As an obvious example, Vertigo’s artwork for LPs by Nucleus or Keith Tippett could easily have sat on progressive rock albums.

The same holds true in some respects for the liner notes, which in those days were usually on the back cover, if there were any. This is also true of jazz LPs in North America, and of folk LPs in both the US and UK, but they had a lot more text in those days, especially toward the earlier part of 1960-75. They were also usually pretty serious in tone, sometimes almost academic and scholarly. While it’s easy to make fun of them for a frequent stuffiness that’s rarely if ever in liner notes of contemporary releases any more, they’re also valuable for the sheer wealth of information, often including the sources for the songs and how the performers found and felt about them. In the later part of this period, they’re also sometimes notable for inscrutable attempts at hipness and stream-of-consciousness prose. Again, what do you think generally were some of the most interesting qualities of the British jazz LP liner notes of the period, and ones that made them distinct not only from other periods, but also from the notes used on LP covers of other genres in 1960-75?

Again, without wanting to make mindless comparisons to pop and rock, I think there was a desire on the part of the musicians or producers of jazz records to impart a clear idea of what was being attempted on a given album, which to me can form a vital part of understanding and contextualising the music.

Most jazz musicians, and certainly leaders / composers, of this era were highly musically literate, and wanted to explain their art in a way that most pop or rock musicians didn’t (Messrs. Townshend and Fripp being notable exceptions), being happy for listeners to form their own relationship with their music without being bogged down by long explanations. I doubt the Beatles gave much consideration to the broader context of their work as they recorded it: they simply moved onto the next thing without pausing to reflect, and found it somehow embarrassing (or ‘soft’) to do so. Either way, earnest sleevenotes ceased to appear on pop or rock LPs as of around 1969, whereas there was plenty of small print on the back of jazz LPs well into the 1970s.

There are few if any others who’ve heard all of the albums you reviewed in Labyrinth, let alone given each of them a considered review. First, a basic question: do you own all of these LPs? I ask because some of them are excruciatingly rare, like those that were produced in editions of 99 copies, or only sold at live performances. Or, in the case of Keith Tippett’s first LP, only pressed as a demo. For the Tony Rushby Sextet’s self-titled 1964 LP, you wrote that only one copy is known to exist, and you can’t get much rarer than that.

Alas, I do not own all the LPs in the book, but I do own most of them, so the photographs you see are almost all of my own copies. I don’t collect privately pressed albums, but that Tony Rushby LP is mine: I bought it cheaply because I recognised one or two of the track titles. It’s not in any way innovative or striking, but it’s a perfectly valid set that gives a vivid sense of a gifted amateur group of the mid-60s, of which there were of course lots. No doubt others made similar recordings that I’m unaware of.

A related question: how long did it take to accumulate and listen to all of these LPs, and what were the hardest ones to find?

I’ve been collecting albums for 25 years or so now, during which time competition for them has greatly increased. In the early 2000s, British jazz was not especially sought-after, certainly not in comparison to psychedelia or progressive rock. That has completely changed, and because in many cases fewer copies were pressed in the first place, the supply have now more or less dried up.

In my experience, certain major label British jazz albums are just as hard to find as private pressings. I guess maybe 500 copies were pressed of something like High Spirits by Joe Harriott, of which maybe half survive, scattered to the winds, almost all in the collections of people who prize them.

Although you must have had most of these albums before deciding to write Labyrinth, I’m guessing you heard and collected quite a few others in the process of doing the book. If so, what were the most interesting and surprising finds and discoveries that you hadn’t previously heard?

I was aware of virtually everything in the book before I started writing it, but the process of collating them and putting them in chronological order did yield some interesting observations, not least how extraordinarily busy and productive certain musicians were: Tubby Hayes, Michael Garrett, John Surman, Mike Westbrook, Stan Tracey, John Dankworth, Ian Carr, Don Rendell and others seem to have been ceaselessly writing, recording and gigging.

There were one or two musical surprises: I hadn’t realized that there was an LP by The Trio (led by John Surman) that had come out only in Japan.

Wearing a tragic collector’s hat, it’s intriguing that certain rare British jazz albums came in both laminated and unlaminated sleeve variants. Examples include Hum Dono by Joe Harriott and Amancio D’Silva, Love Songs by Mike Westbrook, Tales Of The Algonquin by John Surman and John Warren, Phase III by the Rendell-Carr Quintet and Cold Mountain by Michael Garrick. To me that implies that more copies were pressed than one might imagine.

This might be hard to boil down, but can you recommend just a half dozen or so albums to someone who’s interested in getting into British jazz from this period?

British jazz in this period covered a large range of styles, so I think any such list needs to be broken down, and will inevitably be personal.

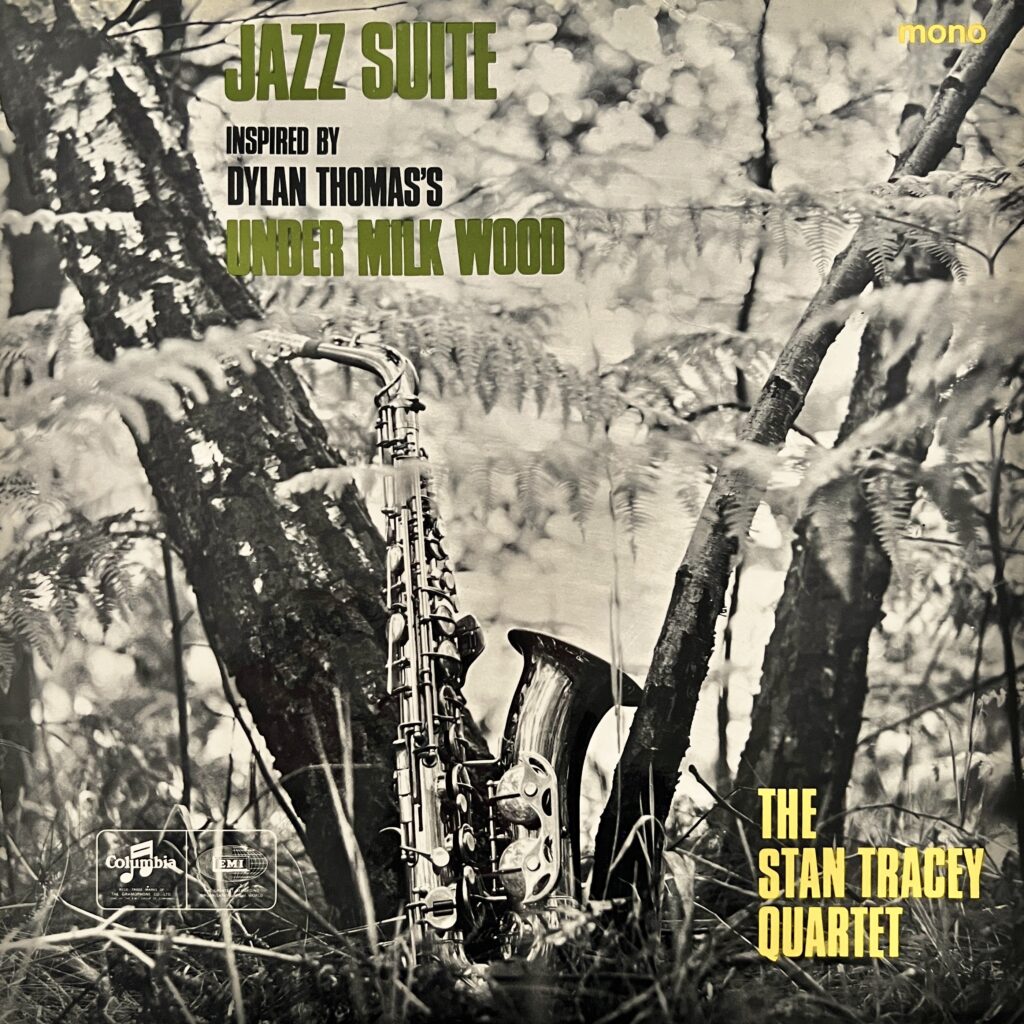

That said… For a small group with horns: Tubby Hayes – Down In The Village, Mike Taylor – Pendulum or Don Rendell – Space Walk. For small piano-led groups: Mike Taylor – Trio or Michael Garrick – Cold Mountain. For larger ensembles: Neil Ardley and others – Greek Variations or the Chitinous Ensemble – Chitinous. For one album that spans various styles across short, melodic tracks: Stan Tracey – Jazz Suite. Recommending avant-garde recordings seems inherently pointless to me, as responses to them are so personal, but How Many Clouds Can You See? by John Surman combines free playing with structured parts to stirring effect. I could go on!

Like a good number of readers of your previous work, I’m primarily a rock fan, and especially of rock from this same time period, 1960-1975. The jazz from this period I like tends to be of the more accessible, rocky, riff-driven kind, like guitarist Wes Montgomery in the mid-’60s and soul-jazz organists like Big John Patton. For me and/or such listeners, what are the British jazz albums you’d recommend hearing that we’d be most likely to enjoy?

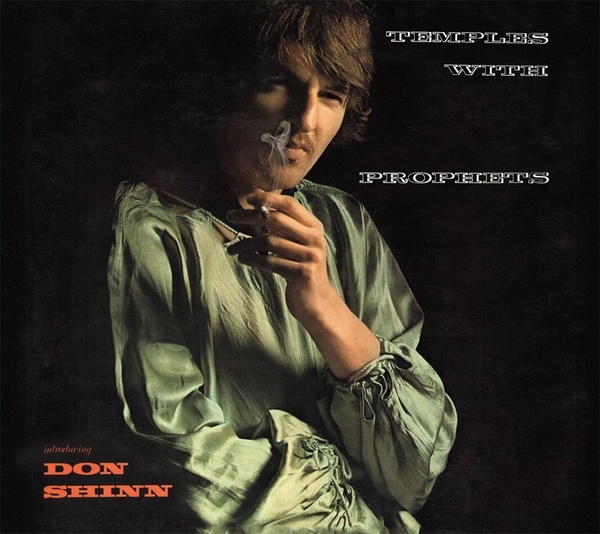

I think it’s a very reasonable question, and many of the jazz records I find most enjoyable are ones that are analogous to rock music, even if they don’t feature vocals or the same instrumentation. So, off the top of my head… Don Shinn – Temples With Prophets, Joe Harriott & Amancio D-Silva – Hum Dono, the Don Rendell / Ian Carr Quintet – Change-Is, Graham Collier – Songs For My Father, Michael Gibbs – Michael Gibbs, Ian Carr – Belladonna.

There’s information on Labyrinth: British Jazz on Record 1960-1975 and how to purchase copies at https://lansdownebooks.com.