According to the liner notes of the recent Mothers of the Invention archive release Whisky a Go Go, 1968, the material on this triple CD was recorded on July 23, 1968 “with the event to be secretly recorded for an upcoming record album.” There was no live Mothers album in the 1960s, and there wouldn’t be one until 1971, by which time there was an entirely new lineup, albeit still led by Frank Zappa.

It doesn’t sound like this recording would have made for an especially good 1968 live LP, and not just because the sound, while pretty good for a 1968 concert recording, isn’t quite as sharp as it should have been for an official release. There’s nothing from their then-recent and brilliant album We’re Only in It for the Money. In fact it seems like they were for the most part avoiding their most accessible songs for not-so-brilliant (certainly without the visuals) comedy and avant-garde-ish improvisation. Maybe they deliberately wanted to showcase sides of their repertoire not heard on their first three albums, but it’s not a great loss it didn’t appear at the time.

This post isn’t a review of the Whisky a Go Go CD, which will be reviewed (and not at great length) in my upcoming year-end roundup of noteworthy 2024 reissues. Thinking about it, however, did make me think generally about how relatively few landmark or “signature” rock albums were made in the 1960s – and how many were attempted, and often released. There were more such concert LPs in the 1970s by the likes of the Allman Brothers (Fillmore East), Cheap Trick (Live in Budokan), and if you want to dig down toward lesser known acts, Humble Pie (Fillmore East again). Or live albums that, if not usually cited as one of an artist’s top efforts, were nonetheless often cited as quite significant for their quality and/or broadening their audience, like Lou Reed’s Rock’n’Roll Animal.

There were good and even great live albums recorded in the 1960s, of course. But even among those, some of them didn’t come out until after the 1960s—sometimes way after the 1960s—and some were only half of a double LP, paired with a studio set.

This post looks at twenty or so live albums by top 1960s acts and how notable they are in the context of their entire discography. It doesn’t survey every notable act of the time by any means; some great bands, like the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield, Love, Them, and the Pretty Things, didn’t put out live albums in their peak years, and didn’t even leave anything behind in terms of unreleased concert recordings that are truly of release quality. Not too many of the live recordings that did come out would be rated as highlights of their catalog, let alone signature albums, although many contain fine music.

The Beatles: Starting with the usual guys who top such lists, although the Beatles didn’t release live albums while they were active, they made a number of attempts. George Martin seriously considered making their debut LP a live recording at the Cavern in Liverpool before deciding, probably wisely, they could replicate their onstage energy with better acoustics at EMI’s London studios. There were hopes to record a live album at their first US concerts at Carnegie Hall in February 1964, but this was thwarted by the musicians’ union.

Capitol Records famously recorded them at the Hollywood Bowl in 1964 and 1965, but the sound quality and performances were not considered up to standard, the Beatles having a hard time even hearing themselves above the audience screams. Some tracks came out in 1977 on the official At the Hollywood Bowl album, and a few more are on the CD, which took many years to come out. They’re fun, but virtually everyone would agree, including the Beatles, that the group were much better in the studio. Not that they were bad live – far from it, but the conditions were so haphazard that no one could have played and recorded near their full potential. That’s also true of several Beatleamania-era concert bootlegs that aren’t too dissimilar, like their 1965 Shea Stadium show or, more obscurely, a 1964 Philadelphia performance.

They considered making a live album—unusually, comprised of new material—in early 1969, though like other ideas floated during the Get Back era, it didn’t come close to getting realized. Some of Let It Be could be considered a live album, since some of it was recorded during their famous January 30, 1969 Apple rooftop performance. While that’s very good, it’s not really a live LP, and wouldn’t be even if the whole rooftop performance was issued separately. That performance was too short to make a full album, especially considering there were some multiple versions of the same song.

There’s also the double live LP of material taped live in Hamburg in late December 1962, not issued until about fifteen years later. Historically interesting it undeniably is, but the fidelity really is subpar – much more so than the Hollywood Bowl tapes. And the actual performances, while sometimes exciting, are also often sloppy.

In a way there is a live Beatles album—several, in fact. Because many tracks from their 1962-65 BBC radio sessions survive, though most of them were recorded in a studio, not in front of a live audience. But the performances are often great, and whether you have them on the official CD sets or bootlegs, they do what many live albums aim to do. They show them playing with a somewhat different, more spontaneous energy than they did in the studio, and very often—three dozen times—playing songs (all but one covers) not on their official studio LPs, quite often resulting in great cuts. This could be said of the BBC sessions of many British 1960s rockers, but no one utilized them as often and as well as the Beatles did.

The Rolling Stones: As great as the Rolling Stones were, few live albums by top ‘60s rock acts missed the mark as badly as 1966’s Got Live If You Want It. The sound quality was substandard, and worse, some of the tracks were obviously studio performances overdubbed with audience noise. There’s actually some good energy here if you make your ears fight through the fidelity, but the live versions are sometimes rushed, and no match for the studio counterparts.

A live UK 1965 EP of the same title (most of which came out on different US LPs) also suffered from non-optimum fidelity, though the performances were better than those used for the US Got Live album. Many Stones fans are probably still unaware that you can get a pretty fair facsimile of what that EP would sound like blown up to a full-length LP as one of the discs on the expensive Charlie Is My Darling box, which is built around the 1965 film documentary of them touring Ireland. With songs like “Little Red Rooster,” “Off the Hook,” “Time Is On My Side,” and “The Last Time” that aren’t on the EP, it almost adds up to a bona fide album, all of it recorded around the same time as the EP that did come out. But it was done shortly before they started writing their best original mid-‘60s songs, “The Last Time” excepted. And the sound quality just isn’t good enough to put this in the top rank, seeming more like a very above-average bootleg for a mid-‘60s live concert—not that there’s anything wrong with that.

Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out, recorded during their US tour in late 1969, is highly esteemed by many, though it turns out some studio overdubbing was later done to the tapes. Certainly it has some pretty different versions of staples like “Street Fighting Man” and particularly “Sympathy for the Devil,” but those actually aren’t as good as the classic studio counterparts. Only “Midnight Rambler” actually surpasses the studio prototype. And Mick Taylor had replaced Brian Jones, meaning there aren’t live Stones relics that capture them with their best lineup, for all Taylor’s estimable contributions.

The Who: Tommy will always be their most well known album, if not always the one most highly regarded by critics. Many Who fans would say Live at Leeds, from just outside the 1960s (recorded in early 1970), comes close, and/or at least certainly ranks among the best live rock albums. In one of my many unpopular opinions, I don’t feel that way, even though I’m a big Who fan. Live their arrangements had gotten too heavy and sometimes overlong for me, as heard not only on the original Live at Leeds, but also on the much longer superdeluxe box, and some other live recordings from the period, both official and unofficial.

The Who did make a serious effort at recording a live album when they weren’t quite as heavy, though still almost as heavy as any band around, at the Fillmore East in April 1968. Recordings from this finally came out a few years ago, and while they’re pretty good, I wouldn’t say they rate among the all-time best of concert tapes from this era. Bonuses include songs they hadn’t put on their records, like the anti-smoking commercial “Little Billy,” a few Eddie Cochran covers, the early soul classic “Fortune Teller,” and some interesting improvisation on the relatively unheralded “Relax.” A big minus is the 33-minute version of “My Generation,” which is ridiculously overlong.

For all the testaments that the Who were a better band live in the ‘60s than on their records—and such accolades are given to many acts, past to present—as actual listening experiences, as opposed to being there when they’re smashing their equipment and such, their concert tapes are considerably less satisfying.

Note, by the way, that some of the Fillmore material was bootlegged for decades from an acetate that Who manager/producer Kit Lambert made of performances from the Fillmore East shows. Some April 5, 1968 cuts from that acetate aren’t on the official Live at the Fillmore East 1968 release. You can be forgiven for wondering if there’s going to be a deluxe version of that in the future that requires completists to buy it, even if they already have much of it on the Live at the Fillmore East 1968 that’s already out.

The Yardbirds: The Yardbirds put out two albums of live 1960s material, though one was only officially available briefly, and not until 1971. The more commonly heard one was their first LP, Five Live Yardbirds, recorded in 1964 with the Eric Clapton lineup. It’s one of the few debut albums by a top ‘60s act that was live, other examples being live LPs by John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, Georgie Fame, and the MC5.

Although the fidelity on Five Live Yardbirds is only fair, it did the job it was supposed to, capturing the Clapton lineup in good form. A crucial advantage being that, unlike the Beatles and Rolling Stones, they weren’t hindered by huge screaming crowds, as this was recorded in a London club before they had a hit record. On “Smokestack Lightning” and “Here ‘Tis” especially they excel—the whole band, not just Clapton—with their signature raveups, instrumental interplay, and hectic improvisation.

But the album isn’t markedly better than the three studio singles they did with Clapton. Actually those singles are arguably on the whole better, with only “Smokestack Lightning” and “Here ‘Tis” equaling them. Even if Clapton hated the last A-side he did with them, their first hit, “For Your Love”—and he is on there, in the middle part.

The story behind the live album they recorded at New York’s Anderson Theatre in March 1968 is different and peculiar. Done with the Jimmy Page lineup a few months before they broke up, it’s okay, but not the Yardbirds or even the Page lineup at their greatest. It’s of most interest for including a pre-Led Zeppelin “Dazed and Confused,” though even that was done better for the BBC and on French TV. As by now is pretty well known, it was exhumed in 1971 as Live Yardbirds Featuring Jimmy Page to capitalize on Led Zeppelin’s success. It was quickly withdrawn due to Page’s objections, and no one was totally satisfied with it even as a souvenir, since it was overdubbed with ridiculous fake audience noise, often termed “bullfight cheers.”

Predictably, this was soon easily available as a bootleg. It was reconstructed without the fake cheers for an authorized 2017 release, Yardbirds ’68. That was naturally better, but not perfect, as most of singer Keith Relf’s between-song comments were taken out. More seriously, some of the musical performances were edited. Five Live Yardbirds was more successful at representing a different lineup, but as usual, the studio recordings were where they were at their best, whether with Clapton, Page, or (especially) Jeff Beck.

John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers: They weren’t among the highest-selling acts of the ‘60s, but they were very important and good. And they put out two live albums. The first, John Mayall Plays John Mayall, isn’t so widely commented upon, likely because it doesn’t feature any of the three guitarists (Clapton, Peter Green, and Mick Taylor) who did memorable stints in the Bluesbreakers. Recorded in a London club in late 1964, it was taped even before Clapton joined, with the relatively unknown Roger Dean on guitar.

It’s actually very good R&B rock, and not too dissimilar from what the Rolling Stones were doing very early on when they were primarily a cover band, a difference being that Mayall wrote most of the LP’s material. Although it wasn’t issued in the US at the time, it became pretty easy to get in the early 1970s, when it was the second disc on the American two-LP compilation Down the Line. But it wasn’t as good as Mayall’s best work with Clapton and Green. There are sketchy and fairly lo-fi albums of live material from both of those lineups, none of them coming close to doing the musicians justice, mostly but not wholly because of the sound quality.

Recorded in the Fillmore East in July 1969 shortly after Taylor left, The Turning Point is actually one of the albums discussed in this post that comes closest to being a signature statement. It’s probably Mayall’s most well known album other than the sole LP the Bluesbreakers did with Clapton, simply titled Bluesbreakers. It ends with what is probably Mayall’s most well known individual track, “Room to Move.”

So why isn’t it a signature statement? Not just because there’s no Clapton, Green, or Mayall. The Bluesbreakers changed lineups so many times that no one album could serve as a signature statement, no matter what one’s individual opinion.

The Doors: Though released in 1970, the double LP Absolutely Live was recorded between July 1969 and May 1970. I’ve always had mixed feelings about the record. On the one hand, it absolutely delivers what many listeners hope to get from live albums, and don’t regularly get: numerous songs, both covers and original, not available (at least in 1970) on studio LPs. Some of the songs that were familiar from studio versions were done significantly differently in concert.

Yet for all that, and decent sound quality to boot, it’s not on par with their studio material. At times—not just here, but on many of the Doors’ numerous posthumous archive concert albums—they don’t seem to be taking the material 100% seriously. It makes for a different angle on the group, certainly, but not as good a one as they had in the studio, where they didn’t joke around.

Absolutely Live is for me something of a neat, quirky footnote to their main body of work. Their March 1967 Matrix recordings, recently assembled in a deluxe box (though some had been previously released, and most had been bootlegged), are easily the best live ones available. They’re quite serious playing this small San Francisco club, a few months before “Light My Fire” became a hit. But the slightly imperfect sound, and performances that, while exciting, can’t equal the magnificence of their early studio discs, and put this out of the top tier of the Doors catalog.

The Beach Boys: I’ve read a rock critic essay, written back in the late 1960s, that slammed the Doors for not being nearly as good live as they were on their records, almost as if they and their producer were cheating. A similar sentiment was expressed in the entry for the Beach Boys in the 1972 book Encyclopedia of Rock’n’Roll, a slim volume that was nonetheless one of the first rock reference books, with the tagline “a concise guide to the young sounds of 1954-1963.” “In person, the Beach Boys were and are nothing short of terrible; but on record, they’re fantastic,” it read. “Brian Wilson turned a mediocre group into one of the best sounds on wax.”

Actually numerous mid-1960s film clips, from when Brian was still performing with the group, are pretty exciting and testify they could play well in concert. You wouldn’t guess it, however, from the one live album they issued in the 1960s, Beach Boys Concert, recorded in 1964. The sound is thin—yes, markedly inferior to the studio versions—the performance sometimes rushed, and the between-song commentary often dated and corny. There are cover versions they hadn’t put on their studio releases, but while their take on “Little Old Lady From Pasadena” is pretty good, no one really needed to hear their version of “Monster Mash.”

The Beach Boys made several attempts at recording live in the 1960s, some of which have come out on archive releases. One batch of recordings from December 1968, Live in London, did come out in 1970, though then only in the UK. Alas, some of the same general problems afflicted other live Beach Boys tapes too. They sounded perfunctory, sometimes even half-hearted, compared to the records. Even more than most top acts who weren’t at their best on live tapes, the Beach Boys didn’t seem to have it in them to make a good concert album, let alone one that would be considered a highlight of their discography.

This didn’t bother listeners in 1964, who sent the Concert album to #1—the only #1 LP the Beach Boys had in the 1960s. Such were the commercial depths to which the group fell within a decade, however, that as an 11-year-old in 1973, I bought a reissue of the album on the budget Pickwick label for a dollar—new, not used. By the following year the group’s live (and general) fortunes revived when the Endless Summer compilation was a #1 hit, though they’d never make a fine live album, or indeed studio records to match the quality of what they’d done in the 1960s.

Bob Dylan: Several attempts were made to tape a live Dylan album in the 1960s, including a couple during his early folk period. Those have come out on official archive releases. So has another concert recording that’s far more famous, of him in Manchester, England in spring 1966. Half of it has him solo acoustic; the other, more renowned and notorious half is loud electric rock with the Hawks (later the Band) backing him. This electric half in particular was bootlegged for almost thirty years before the whole show, which had often been erroneously labeled as recorded in London’s Albert Hall on bootlegs, was officially issued on CD.

It could have easily come out as a stopgap release in 1967, when Dylan was out of the public eye after his famous summer 1966 motorcycle accident. Maybe it was felt his Greatest Hits compilation, which did come out to fill the gap, was a better bet. Had it come out shortly after it was recorded, it probably would have been enthusiastically received, especially as both the acoustic and electric arrangements often differed notably and interestingly from the studio versions.

But would it have been received as a signature statement? I don’t think so, in part because while Dylan didn’t have a reputation as a focused studio perfectionist, actually the studio versions were more focused, with better fidelity. And, in cases where electric rock studio tracks were done as solo acoustic tunes (like “Just Like a Woman”), the studio rock versions were simply better and fuller.

It would be interesting to see how this Live at Albert Hall (as it was frequently mistitled) album would have fared back in 1967. Not so much on the charts, where it almost certainly would have done well, but with listeners and critics. I think it would have been viewed as a very good and cool supplement to what Dylan had done in the mid-1960s, but not better or equal. The luster it acquired among many critics and listeners might have been inflated by its very rarity, or at least lack of easy availability for those not aware of how to acquire unauthorized recordings. Those who were perhaps felt like they were being let in on a secret, or given access denied to much of the public.

Jefferson Airplane: More than any other item on this list, the Airplane’s late-‘60s concert album, Bless Its Pointed Little Head, falls in between a disappointment and a signature record. It never seems to have been intended as either a major statement or something to fill out a release schedule. It was just a decent concert recording that gave satisfyingly different, but not radically different, arrangements than what they were doing in the studio. There were good covers they didn’t fit on their studio albums, like “The Other Side of This Life” and “Fat Angel.” It was a worthwhile part of their discography that, to use a cliche, did what it was supposed to do, or what live albums were supposed to do, pretty well.

Pink Floyd: Ummagumma in some ways approached being a signature album, at least in the US in 1969, where (unlike in the UK and some other countries) they were just becoming widely known. So many listeners wouldn’t have heard the original studio versions of the songs that comprised the live half of the LP: “Astronomy Domine” (the original of which actually wouldn’t be issued in the US for many years), “Careful With That Axe, Eugene,” “Set the Controls For the Heart of the Sun,” and “A Saucerful of Secrets.” The last three of these were pretty similar to the studio versions in some respects, but with four songs occupying two sides of an LP, were more drawn-out. The sound was excellent—indeed, much better than most of the rock concert LP competition.

And even as a big fan of the Floyd’s Syd Barrett era, “Astronomy Domine” was the definitive version. Doubling the length of the studio track on their first LP, the David Gilmour lineup simply surpasses the prototype here, with superb alternation of tense passages building to creepy crescendos and languid, reflective spaced-out ones.

Although Ummagumma was successful in expanding the band’s following in the US and internationally, there’s a simple reason it wouldn’t have been received as a signature album. It’s hardly a secret, but the second disc in the two-LP set had studio performances of new material. Except for “Grantchester Meadows,” it wasn’t in the same league as the songs on the live set.

But the group doesn’t seem to have intended this to be solely a studio or solely a concert record; the intent seems very much to have mixed both. Maybe if they’d decided to make a double live LP featuring some of their other best early songs, and adding a live version of “Grantchester Meadows” (which they could do very well live, as some recordings prove), it would have been greeted as a major concert record. But this wasn’t the case, and Pink Floyd wouldn’t issue another live or even partially live album during their prime.

Cream: As long as we’re on half-live/half-studio double albums, Wheels of Fire was not just a lot more popular than Ummagumma, but the most successful such record of the era, and maybe of all time. Commercially, that is; it made #1 in 1968. It had pretty good music, if more on the studio disc, which besides the big hit “White Room” had some of Cream’s better studio tracks, like “Politician” and “Born Under a Bad Sign.”

At the time, the live part might have been at least as popular, with “Crossroads” and the most famous (or infamous) rock song of the period with a long drum solo, “Toad.” Now, and for some listeners even then, it wasn’t as good as what they did in the studio. Besides “Crossroads,” the four tracks were just too long and indulgent. It did function as a representation of something they wouldn’t put on studio albums, showcasing their lengthy improvisations. But besides this getting disqualified as a signature album because half of it isn’t live, it wouldn’t hold up as a highlight of Cream’s work owing both to its lesser quality than their studio material, and not reflecting all or even most sides of their repertoire and sound.

Jimi Hendrix: Sticking with heavy rock for a bit, Hendrix put out just one live album during his lifetime, though there are many – not just a half dozen – live albums available now, and indeed they continue to get issued posthumously fairly regularly. The one that came out while he was still alive was Band of Gypsys. This is also the only non-posthumous one with the actual Band of Gypsys, Hendrix playing with bassist Billy Cox and drummer Buddy Miles. Recorded on New Year’s Day 1970, its release was at least partially motivated by a complicated contractual obligation rooted in a dispute with a former producer.

Quite a few years ago, a review of a reissue of this called it the jewel of the Hendrix catalog. I don’t see it that way at all, and I think a pretty low percentage of Jimi’s fans view it as the jewel, or even one of the best of his records. Certainly it’s interesting, and “Machine Gun” does rate as a highlight of his catalog, if we’re just talking songs. But though some fans and critics feel he should have been playing with more soul/R&B-rooted musicians instead of the original Experience, this isn’t as good or versatile as what Hendrix did with Mitch Mitchell and Noel Redding. It’s heavier blues-soul-rock, sometimes sluggish and overlong. Just the presence of Buddy Miles as sometime lead vocalist eliminates this from being close to Hendrix’s best, though Miles’s “Changes” was one of the best songs.

Like some other albums in this post, this has been given an expanded CD treatment. In this case, a very expanded one, as there was a five-CD box of his Fillmore East sets from December 31, 1969 and January 1, 1970. It gives you quite a few more songs and the expected multiple versions of songs from the original LP, but doesn’t change my general evaluation.

Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young: Although some critics don’t regard this too highly, 4 Way Street comes closer to being a signature album than most of the entries here. Of course that’s helped by CSNY (at first as CSN) only putting out two studio albums during their prime. But 4 Way Street was an extremely successful record, getting to #1 as a double album. Just as importantly, the two-LP format gave the group a chance to present songs not on their studio albums, and in formats that their studio LPs wouldn’t have allowed.

Specifically, there was the chance to hear solo performances, or performances by only part of the group, that were regular features of their concerts. There were extended versions of some of their most popular songs, particularly “Carry On.” There were some of the most popular songs they did outside of CSNY, like Neil Young’s “Southern Man,” extended to thirteen minutes, Stephen Stills’s “Love the One You’re With,” and Graham Nash’s “Chicago.” In these respects, it was more representative of their concerts than their studio work.

Still, these tracks weren’t as good as the studio versions, though they often gave a distinctly different slant to them. The performances themselves weren’t always 100% tight. If there is a signature CSNY album, it’s Déja Vu, another #1 record, and the only one from their brief prime to have Y (Young) as well as CSN.

The Grateful Dead: Speaking of double live albums, what about 1969’s Live/Dead? Certainly it’s the most highly esteemed of their non-archival live records, even if some might vote for Europe ’72. But there’s so much live Grateful Dead—and with so many Deadheads avidly collecting their official and unofficial live tapes, it’s not a peripheral part of their catalog—that nominating any single live show or collection would be difficult. And while both the band and much of their audience don’t consider their studio recordings as important as experiencing the Dead live, their 1970 albums Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty are both easily their most highly regarded studio LPs and quite different from their live albums/tapes. I think they’re better, too. But their prominence would make it impossible to select any one Dead album, live or not, as the cream of the crop.

Quicksilver Messenger Service: Acts with brief careers, and certainly brief primes, are at an advantage for a live LP getting pegged as definitive, simply because there’s less competition within their discography. Quicksilver’s career actually wasn’t all that short, but almost everyone would agree their peak period was the late 1960s, before their lineup altered when Dino Valente joined. They only put out two LPs in that time, with the live one (and second of the pair), Happy Trails, being the more famous and successful. Most Quicksilver fans—those that are left, as they aren’t among the most well remembered acts of the era—would vote for Happy Trails as their signature album.

I know I’m outvoted, but I’m not a big fan of Happy Trails. Their sheer length of “Who Do You Love,” taking up all of side one at 25 minutes, is chiefly responsible for its popularity, but I find it way too long and not all that interesting. Side two, which got lots less play, doesn’t do too much for me either.

Lest it seem like I just don’t like Quicksilver, actually I do like them during this period—much more than I do the Dead, for instance. But although their self-titled studio debut LP was sometimes criticized as not being that great or reflective of their strengths as a live act, I think it’s pretty good, and certainly superior to Happy Trails. The necessity of working in the studio, as it often does, seemed to focus the arrangements more and orient the song selection toward fairly succinct ones, like their career highlight “Pride of Man.” Even the seven-minute “Gold and Silver” instrumental doesn’t have wasted space.

If fans who were there might maintain Happy Trails doesn’t wholly capture their live glory, by this time there are quite a few official and unofficial live Quicksilver releases from the era. They have their moments, and I would say some are better than Happy Trails. Yet none of them are as good as that underrated studio debut, Quicksilver Messenger Service.

The MC5: More than Happy Trails, and more than any other album here, Kick Out the Jams is the album most people think of first, or even think of only, when it comes to this particular act. While not exactly a hit record, it was easily their most widely heard, and certainly their most notorious—indeed, one of the most notorious from the whole era. Live debut albums are unusual, but this one did make an impact and to some degree define the group, even if it didn’t sell the loads of copies that some might have expected.

To present an unpopular opinion, I’m not a big MC5 fan. Lester Bangs wasn’t a fan of the record when it first came out and he reviewed it. But more to the point, the sound quality isn’t sparkling, and sheer volume and outrage outweigh the quality of the material, which often isn’t that strong. While this gets into revisionist snobbery, their rare pre-LP singles (not so rare now that they’ve been reissued on CD) have sharper playing, and even if the fidelity isn’t top-notch, the energy’s off the charts. The record’s legendary status might have as much to do with their revolutionary reputation and the pure outlandish in-your-faceness of the disc than its inherent merits, and the subsequent controversy it caused when Elektra Records dropped them from the label after the band took out a profane ad with unauthorized use of the Elektra logo.

But although the MC5’s later albums have their champions, not many would favor them above Kick Out the Jams. It overshadows the other records they put out in their original incarnation, and is certainly the first one that comes to mind when the group’s recorded legacy is considered, even among people who aren’t big fans.

The Great Society: Here we have a case where a notable group’s live albums aren’t just their signature statements, but almost their only statements. Most famous for featuring Grace Slick before she joined Jefferson Airplane, the Great Society only managed one barely distributed single (with an early version of “Somebody to Love,” then titled “Someone to Love”) before breaking up in late 1966 when Slick left. To capitalize on Slick’s fame, two albums of live recordings from mid-1966 at San Francisco’s Matrix club were issued in 1968. But they’re not mere historical footnotes. The Great Society were a fine group in their own right, and blended improvisation, jazz, raga, middle eastern music, and folk-rock into innovative and often excellent early San Francisco psychedelia. Early versions of “Somebody to Love” and “White Rabbit” are on the first and better of the two LPs, Conspicuous Only in Its Absence. But the albums have plenty of fine original songs not available elsewhere, and some good covers.

An album’s worth of earlier demos for Autumn Records was issued several decades after these two LPs, so they no longer represent close to 100% of their discography. Those demos show the group in much rougher and less impressive form. So Conspicuous Only in Its Absence and its follow-up How It Was, which have been combined onto one CD, very much overshadow anything else on record by the Great Society. I can’t think of another instance where a significant 1960s rock act is only represented well by live albums.

James Brown: There were plenty of live 1960s soul albums, and though I’m not covering those in this post, I’ll make an exception for one artist. Brown’s Live at the Apollo, recorded in 1962, is sometimes enthused about as if it’s not only one of the greatest live albums, but one of the greatest albums, period. Here’s another instance where I’m probably outvoted, but even as a Brown fan, I don’t share that opinion, and in fact don’t find the record that exciting. It’s less oriented toward his uptempo material than you might expect, and predates his move into his absolute prime in the mid-to-late 1960s when he pioneered funk.

Since Brown (and many soul and rock artists of the time) didn’t pay nearly as much attention to crafting fine full-length albums as making hit singles, there aren’t standalone studio LPs that are nearly as good as his compilations. He did record more live albums, the best of which is the double LP Live at the Apollo Vol. 2, recorded in 1967. If everything on that record was as good as the thrilling near-continuous melody of funk (including “There Was a Time” and “Cold Sweat”) that takes up all of side two, it might just stand as Brown’s best recorded statement, or certainly best album, though his best singles would still be his greatest achievements. But the other three sides of that double LP aren’t nearly as good or cutting-edge, including some of his older ballads, perfunctory covers, and ridiculously short versions of “Out of Sight” and “I Got You (I Feel Good).”

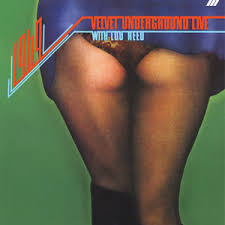

The Velvet Underground: The Velvets didn’t put out a live record when they were active, and that doesn’t seem to have been seriously considered. They weren’t such big record sellers that their labels would be eager to inflate their catalog with a live release. This changed when Lou Reed rose to prominence as a solo artist, and the VU in general started to get more and more deserved accolades for the pioneering quality of their music. Even before “Walk on the Wild Side,” Atlantic had issued, in 1972, a lo-fi recording of them in summer 1970 at Max’s Kansas City (taped on cassette).

The Velvets’ live brilliance is far better represented by the terrific double LP 1969 Velvet Underground Live, recorded at various San Francisco and Dallas gigs in autumn 1969, but not issued until 1974, with Reed’s name in the subtitle. It’s notable not just because of the sky-high quality of the music. It also shows how, much more so than most top bands, they could change around and almost redefine their songs in performance, sometimes with arrangements that were decidedly superior to the studio versions, such as their extended version of “White Light/White Heat.” There were also good songs that hadn’t appeared on their studio albums (or even Reed’s solo albums), like “Over You” and “Sweet Bonnie Brown/It’s Just Too Much.”

But is this the Velvets’ best and/or signature album? Their first LP, 1967’s The Velvet Underground & Nico aka “The Banana Album,” will always be their most famous album by far. There are good reasons for that: besides the basic classic worth of the music, it has some of their best/most celebrated songs, and is the only LP with Nico, though she sings lead on only three tracks. It’s not a signature album since each of their four studio albums were quite different, and worthy in their own way. But their subsequent records will never be as widely hailed, as good as they were.

And 1969 Velvet Underground Live was very good—almost as good as The Velvet Underground & Nico, I’d say. And in some ways more representative of their range, not only because it encompassed material from all three of their first three albums and then some, but also because it had sweet romantic ballads, pummeling proto-punk, joyous celebratory rockers, and more, testifying to the underrated breadth of their repertoire. Some listeners would automatically fail to consider this their best or nearly their best because of the absence of John Cale, who’d left the group in late 1968. But with his replacement Doug Yule, they did reach their peak as a live act, and while these tapes were not originally intended for an album, they couldn’t have captured them better in concert. If not the signature album of the Velvet Underground as a whole, it could certainly be considered the signature album of their underrated period with the Yule lineup.

Hey Richie,

It’s always such a pleasure to read you. My comment will be a little biased since we have already had the opportunity together to dig into the subject: what place would you give to the live album “Hot Tuna: Live from the New Orleans House” recorded in Berkeley in 1969 ? I think for my part that it deserves its place in the list of live rock recordings of the 60s, quite atypical and unique since it presents two musicians then members of Jefferson Airplane (Jorma Kaukonen and Jack Casady) in an acoustic “pre-MTV unplugged” atmosphere that is at the very least intimate. The duo accompanied on several tracks by local harmonica player Will Scarlett explores the country blues roots of rock with a dizzying inventiveness and virtuosity, a sort of acoustic Cream if you will, ideally produced by Jefferson Airplane then-producer, the mighty Al Schmitt.

Can the “live rock” classification be a problem? Well, such a combination of an acoustic guitar and an electric bass is quite special, a prefiguration of the Americana style in a way.

The unexpected success of this album brought the two musicians to the stage of the Fillmore East in July 1970, “as quiet a concert as has ever been heard at the Fillmore East” the New York Times journalist Mike Jahn wrote.

Hot Tuna’s debut is probably their most well known and most loved album, and thus makes a case for being a signature album. One thing that could work against it being considered one is that it doesn’t represent the electric side of their sound, which they’d go into on some of their other records.