Richard Morton Jack’s new book Pressing News: British Music As It Happened 1962-1972 is the kind of book whose interest is pretty limited to intense historians/collectors/fanatics, and that you use for reference rather than reading all at once, or even in its entirety. That doesn’t mean it isn’t valuable, of course, built around reproductions of more than a hundred press releases for British rock artists between the early 1960s and early 1970s. Usually the releases are tied to specific records, from the most famous (Sgt. Pepper) to some by very obscure acts (Fresh Maggots, Jerusalem, and the Pete Best Four, to name just a few examples). These are accompanied by quite a few reprints of reviews, and sometimes full stories, that appeared about these records and acts at the time, not years later, when critical views about the performers and their importance often shifted. There are also reproductions of some ads from the period, and each entry has a substantial paragraph from the author explaining the context of the material and the performers’ career at the time.

A little disappointingly—and this has nothing to do with the talent of the author and the usual fine design he brings to his specialized books—the releases themselves (and the reviews) are often bland and basic, if reflective of how the industry promoted rock at the time. There aren’t a ton of genuine surprises, though it’s a great service to have reviews from UK music papers reprinted, as (except for Melody Maker, and to extent NME) accessing the ones from British weeklies is difficult, even for the major Disc and Record Mirror publications.

Morton Jack also dug up quite a few items from general interest/regional newspapers and magazines that have seldom been seen since their publications, going back to a few (such as a review in the Newtown & Earlestown Guardian) for the book’s first entry, on the Beatles’ “Love Me Do” single. Almost all of the reviews and stories, incidentally, are sourced from UK publications, though a very few from the US are present. While it’s unlikely every reader wants to go through the clippings and releases for all of the selections depending on their taste (especially the more esoteric ones from the late 1960s and early 1970s), there’s something for every fan of British rock of the period here, from the superstars to worthy cult acts like Blossom Toes.

There are some surprising nuggets here and there for British rock obsessives. I’m detailing some of the ones of most interest to me in particular in this post. I interviewed the author in my next post:

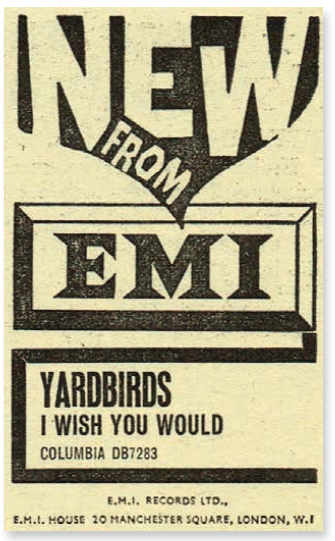

** The Yardbirds are justly hailed for pioneering blues-rock and psychedelic guitar work, often with volume, especially with the guitar, that was loud for the time. Yet in a press release for their first single (“A Certain Girl”/ “I Wish You Would,” May 1964), lead singer Keith Relf revealed, “Actually, up until last year I was a real purist, wouldn’t have anything to do with electricity.”

** The Zombies were most highly esteemed for their wealth of fine original material, usually written by either keyboardist Rod Argent or bassist Chris White, though singer Colin Blunstone wrote a bit. They are not highly regarded for their occasional R&B/soul covers, though they did a few good ones, some of which (like “The Look of Love”) were only done for the BBC rather than for their official releases.

So it’s a little surprising, in a press release for their first LP (UK version), to see road manager Terry Arnold cite a cover as the most interesting song. “Probably the most interesting track is ‘Sticks and Stones’—it’s a slowed-down version of the oldie that Ray Charles made famous,” he states. “The boys give it a really earthy feel.”

** Vashti isn’t a name known to the average rock fan, but she’s pretty well known to the kind of people who read these blogs, if mostly for her cult 1970 folk album. Five years earlier, she had a brief career as a more Marianne Faithfull-like folk-pop singer, including the single “Some Things Just Stick in Your Mind,” written by Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, and produced by Rolling Stones producer/manager Andrew Oldham. According to a press release for that 1970 LP (which misspells the title as “Somethings Just Stick in Your Mind”), “Although the disc sold as many as were pressed, for some unknown reason, Decca stopped production.”

It seems it would be highly unusual for a record label to stop pressing a single that had sold out. Could this not have been accurate—misstatements and outright untruths, as shocking as it sounds, not being unknown in press releases then and until the present? This is supported by Vashti Bunyan’s memoir Wayward, in which she writes, “the single went nowhere,” and doesn’t refer to it selling as many as were pressed and production getting stopped. Maybe, say, only fifty were pressed and they all sold, but that seems highly unlikely.

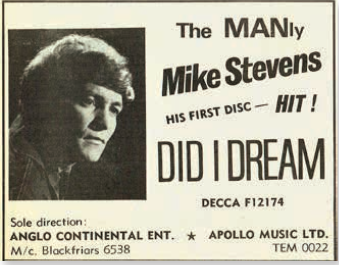

** Welsh singer-songwriter Mike Stevens is another name not known to the average rock fan. Like Vashti, however, he’s pretty well known to the kind of people who read these blogs, but under a different name: Meic Stevens. But he was billed as Mike Stevens when his first single came out in 1965. All very footnotish, but in the “Lifelines” section of a press release for that June 1965 single, Robert Johnson is listed as one of his favorite singers. Johnson is today extremely famous, but in 1965 he was known only to a pretty small cult of folk/blues enthusiasts. It wouldn’t surprise me if Stevens was the first to list him on a “Lifelines” or similar list.

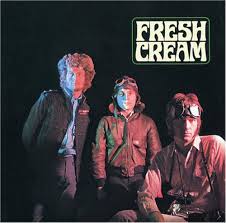

It also might seem unusual Stevens even found any Johnson records in the UK, though the first Johnson LP compilation had come out in 1961. But was it as unusual as we might think? Eric Clapton made his debut as a lead singer on a cover of Johnson’s “Ramblin’ On My Mind” on the famous 1966 Blues Breakers: John Mayall with Eric Clapton album. I’m guessing that’s the first Johnson cover by a rock act (though the Bluesbreakers might have preferred to think of themselves as a blues band), predating Cream’s cover of “Four Until Late” on their first album in late 1966.

So Clapton found something by Robert Johnson in the UK, but was it as rare for young British musicians to find obscure (or at least then-obscure) American blues as we might think? Some such LPs were available at specialty shops like Dobell’s on Charing Cross Road in London. It’s been reported that Syd Barrett named Pink Floyd after coming across the names of Pink Anderson and Floyd Council in the liner notes to Blind Boy Fuller’s Country Blues 1935-1940 LP. It’s unclear how much he and the other members actually heard Anderson and Council, if they heard anything by them at all, or if or how much they heard Fuller for that matter.

** It’s well known, among serious Who fans at any rate, that they finished or almost finished a debut LP dominated by R&B/soul covers before abandoning it and making a better one dominated by Pete Townshend originals. It’s not so well known, though this was likely the source for historical writing on the issue, that Beat Instrumental had a comprehensive July 1965 story on the first version, which they reported “has been completed.” Producer Shel Talmy played reporter John Emery an acetate with nine tracks, and Emery—with unusually acute observation by the standards of the mid-‘60s pop press—was hit “slap in the face just looking at the titles [by] the lack of originality in choice of material.” Eight of the nine tracks were cover versions, and although some were used on the My Generation LP and all the others named in the piece have come out on archival releases, this would indeed have made for an underachieving core of a debut Who longplayer.

To list the precise tracks cited: James Brown’s “I Don’t Mind” and “Please Please Please” (both of which did make the My Generation LP), Bo Diddley’s “I’m a Man” (which also made the LP, although only the UK version), Martha & the Vandellas’ “Heat Wave” (re-recorded for the Who’s second LP, although only the UK version), “Motoring” (the flipside of Martha & the Vandellas’ hit “Nowhere to Run”), “Leaving Here” (first done on Motown by Eddie Holland), “Lubie” (the most obscure item, first done by Paul Revere & the Raiders), and “You’re Going to Know Me,” the sole Pete Townshend original. The description (“is opened with guitar strumming and bursts into an uptempo raver. There is some feedback used here”), makes it obvious this was an early title for “Out in the Street,” which did lead off the My Generation LP.

If you’ve noticed the math doesn’t add up, you’re right. That’s seven cover versions and one original, though the acetate had nine tracks. The identity of the ninth one is unknown. Whatever the case, the Who were certainly right to redo the album for the most part. The Who did some good R&B/rock covers in 1965 (especially the B-sides “Daddy Rolling Stone” and “Shout and Shimmy”), but that wasn’t their forte, and the outtake covers aren’t that hot. They’re rather dull, actually, which isn’t something you’d say about anything on the final My Generation LP.

** Speaking of My Generation, Marc Bolan—then barely known, and barely recorded—had this strange comment on the album in the February 19, 1966 issue of London Life: “The song ‘My Generation’ really swings but for me this is a bad LP. Nevertheless, for the track ‘My Generation’—the LP is very much worth buying.” It would have been quite an investment for the average young British rock’n’roll fan to buy an album for just one track—one that would still have been easily available as a much cheaper hit 45.

** In a Record Mirror interview published on August 13, 1966, just after Cream formed, Eric Clapton was asked what he thought of the Yardbirds’ new self-titled album (since often called Roger the Engineer). He was most uncharitable about the band he’d left in early 1965, to be replaced by Jeff Beck. “I just don’t want to know, he said after what the paper reported as “a short snort.” “One of those numbers I gave to them two years ago and arranged it and everything.” It would be interesting to know which one that was—maybe “Lost Woman,” basically a rewrite of Snooky Pryor’s “Someone to Love Me,” which the Yardbirds did play with Clapton, as it’s on an archival release of a July 1964 concert.

Sadly, Clapton wasn’t done dumping on his old band and others. In the same feature, he went on to carp about the Yardbirds, “They do this thing about Keith Relf collapsing five minutes before they go on stage, then they pull the whole band out. Everyone’s waiting for the big split”—which wouldn’t happen for a couple years, but after a couple major lineup changes. Asked to rate fellow guitarists, he had good if brief words for Jeff Beck and Peter Green, but added, “If I was sure that everything George Harrison played was his own ideas, I’d say he was good, but I’ve got this feeling it’s Paul McCartney telling him what to do.” That was considered colorful enough to be rephrased for the article’s headline, though if George read the piece, he apparently didn’t hold grudges, he and Clapton famously becoming close friends within a couple of years.

Finally, Clapton stated “there are only about four groups in the country who are developing their own directions—the Beatles and the Kinks, and the Small Faces and the Who I suppose.” The Yardbirds were conspicuous by their absence.

** John’s Children are a group known more for their overhype than their music, though actually some of their records were pretty good. They never did make it over to the US, though there was more than one report of them coming over to capitalize on the success of their “Smashed Blocked” single in some Californian markets. One such report is in a February 1967 press release, which claims “there’s the chance of an American tour in March.” An easy claim to back out of when the chance didn’t come through, but it goes on to read, “and a Monkees-style TV programme for them while they’re over there.” Who knows if there was anything to that or just a flight of fancy to gain them attention, but there’s barely even any surviving film footage of the group, let alone a full TV program.

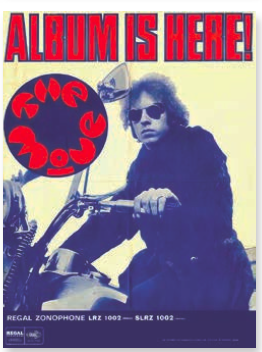

** As the Move had their first UK hit single in January 1967 and three big ones in the country that year (though they’d never make it in the US), it’s odd their first LP didn’t appear until more than a year later. This is how Morton Jack summarizes it in his text: “The Move’s debut LP was promised for November 1966, with publicity-hungry manager Tony Secunda bragging: ‘Our aim is to outdo Revolver with new musical innovations.’ The date came and went, but in the spring of 1967 Rave magazine reported ‘The Move’s first album, called Move Mass and due out soon, contains some really weird tracks…There’ll be one called ‘Kilroy Was Here’ and another provisionally titled ‘Roy Wood’s Toytown Band,’ which features the group playing toy instruments.’ On April 24, however, Secunda announced that the tapes had been stolen from their agent’s car in Denmark Street. Work on it stalled thereafter, as they gigged relentlessly, moved from Decca to EMI, lost a libel action brought by the Prime Minister and weathered bassist Ace Kefford’s mental difficulties. Late December was promised, but the LP didn’t appear until March 1968.”

That’s a really long period of gestation, and I have to wonder if the story about the tapes getting stolen—not something that often happened to an act with hits and a high profile—was planted to stall for more time if progress on the LP was laborious. (And what was the agent doing with the tapes anyway, and why would it have been the only copy?) “Kilroy Was Here” was indeed a song, and a good one, that was featured on their debut album, though it’s unclear whether it was re-recorded if tapes were actually stolen. No track titled “Roy Wood’s Toytown Band” appeared on a Move release, and going from the description, that might be a blessing. Incidentally, the album title reported back in spring 1967, Move Mass, wasn’t used, the debut LP bearing the most unimaginative title The Move.

** Speaking of overhype, the Idle Race were a good-but-not great group most known for including Jeff Lynne before he joined the Move, let alone co-founded Electric Light Orchestra. A Liberty Records ad from October 1968 is headlined, “First album from the group second only to the Beatles!” At least John’s Children’s overhype was making some outrageous and dubious claims as to their burgeoning success, and not anything along the lines of “second only to the Who,” though they did support the Who on a rambunctious German tour. The Idle Race did have some elements of the Beatles at their lightest, though they were considerably closer in sound—though again, in a notably lighter fashion—to fellow Birmingham group the Move. And they never did get a hit, let alone challenge the Beatles in sales or innovation, though they have their cult following.

** In the November 23, 1968 issue of Melody Maker, Long John Baldry—a much bigger name in the UK than in the US, where he made virtually no impression in the 1960s—commented on Fleetwood Mac’s new “Albatross” single, and not very positively. “It’s a bit Roy Rogers and Trigger riding into the sunset,” he surmised, before really digging the knife in: “I don’t see the point of this record by any standards—pop, blues or jazz. I don’t see what it’s got to do with anything.” He also predicted “it won’t get into the pop market because it doesn’t mean anything”—most inaccurately, at least for the UK, where it got to #1.

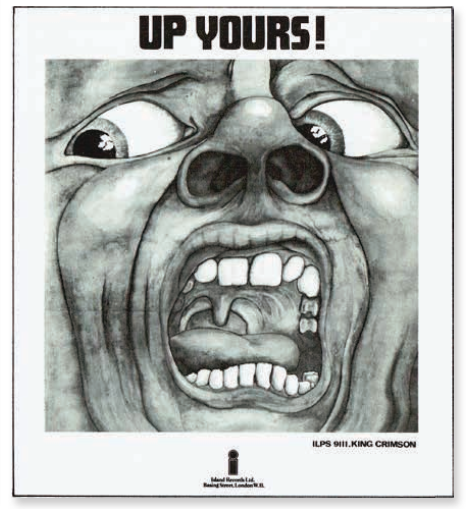

** In the June 7, 1969 issue of the now-forgotten UK magazine Top Pops, a sidebar to a feature on the emerging group King Crimson—who had yet to issue a record—listed four favorite pieces of music by each member. The original King Crimson, and the one album they recorded, are rightfully thought of as cutting-edge hip. Their lists, however, remind us that not everything cited as cool and influential at the time by cool and influential musicians is what we’d expect, or what has been with codified as unhip and uninfluential. Folky material figured surprisingly strongly, Robert Fripp listing Judy Collins’s “First Boy I Loved” (her version, not the original one by the Incredible String Band); Greg Lake listing Collins’s “Michael from Mountains” (her version, not the one by the writer of the song, Joni Mitchell); Michael Giles listing Simon and Garfunkel’s “Old Friends”; and Greg Lake listing Donovan’s “Deed I Do” (Donovan’s “Get Thy Bearings” was covered by King Crimson in concert in 1969, as heard on archival releases).

As far as unhip, Ian MacDonald lists Vanilla Fudge’s “Break Song.” Lake lists the Moody Blues’ “Never Comes the Day,” and although the Moodies aren’t rated as high as King Crimson by many rock historians, there were more similarities between the bands than many are willing to acknowledge. Of course they both used Mellotron heavily at the time, but also Moody Blues producer Tony Clarke worked on King Crimson’s first album before the band took the production reins themselves.

** Syd Barrett’s solo work might not be as highly regarded as the godhead stuff he did as Pink Floyd’s leader on their first album and handful of singles, but it’s generally felt to be at least interesting, and by some to be charmingly whimsical. Not so the Newcastle Sunday Sun, which gave his first album a pretty harsh rundown on January 25, 1970. “Judging by the sleeve of…The Madcap Laughs, Syd sings to a naked lady these days,” it reads. “Either the stool she is perching on is a trifle chilly or she finds Syd’s serenading troublesome.

“Syd’s all right doing his own thing as long as everyone concerned helps him along. They seem to impress on each other how good and groovy it all is really. In the end, they seem to persuade themselves, and reach a point at which they cannot distinguish between junk and genius.”

** Scott Walker briefly reverted to his birth name, Scott Engel, when he went in his most serious singer-songwriting direction on his fourth LP. Although that was his best and most artistic record, it wasn’t a commercial success, and he subsequently become Scott Walker again, never again reaching the heights of his simply titled 4 album. While he was still Scott Engel, however, he gave an interview to the now-forgotten paper Music Now for its December 5, 1970 issue. Here he disclosed a surprising and interesting ambition: “I am interested in Russian music. I have got great sympathy for the people over there. I would like to do a ‘political’ album, for want of a better word. It would be about life there and the lives of the people.” Elsewhere in the story he claimed, “I think I probably have the largest collection of Russian classical music in London.”

That record never did come out, and perhaps would not have been welcome in a Western world unsympathetic to Russia, as it often has been to the present day. Although Walker was noted for crediting non-rock influences like Frank Sinatra, Jacques Brel, and Russian classical music, and incorporating them into his work, in this story he does compliment a couple rock stars, Neil Young and the Band. More surprisingly, he adds that “Johnny Winter is another person I respect. I have played with a lot of good guitarists and I’ve seen a lot too, but he beats so many of them. He plays real shit-kicking music”—though most would fail to hear even an echo of Winter in Walker.

** Trader Horne, the duo of ex-Fairport Convention singer Judy Dyble and ex-Them keyboardist Jackie McAuley, lasted for just one 1970 album. Apparently more ambitious plans were afoot, as Dyble said in a June 1970 story in Beat Instrumental they were going to the US in August. They never made it over, as Dyble left in May, around the time the Beat Instrumental story would have appeared.

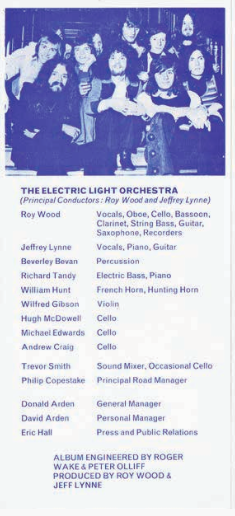

** The transition of the Move into Electric Light Orchestra remains a puzzling and odd period, as it seems these acts were envisioned as having overlapping careers, although in fact the Move ended only very shortly after Electric Light Orchestra began (and ELO only included the Move’s Roy Wood for a short time). A press release from December 1971 seems to indicate plans were different, Wood “clarifying,” “We can still expect to hear new records from the Move for another three years or so, but live appearances will be rare.” Actually the last Move release, the single “Do Ya,” would come out only half a year later, in June 1972.

Information about Pressing News and how to order a copy is at https://lansdownebooks.com/products/pressing-news.

“lead singer Keith Relf revealed, “Actually, up until last year I was a real purist, wouldn’t have anything to do with electricity.” … Somewhat ironic given the circumstances of his death.

That’s right. For those readers who might not understand the reference, sadly Relf died when he was electrocuted while playing music at home in 1976, only 33 years of age.

Very interesting. Have you seen the “worldradiohistory.com” site where you can search and see hundreds of scanned uk music papers and magazines from the 1950s to the 1990s? Loads of other stuff too.

I’ve wasted many happy hours there.

Artie

Yes, I’ve been to that site. It’s very useful, though unfortunately it doesn’t have complete runs of the magazines.

There is a promo video of John’s Children for “Smashed Blocked” on youtube as well as a couple of silent concert films out there.

Thanks, I’ve updated the post to note there’s some footage.