Of the three categories I prepare year-end best-of lists for, books have, at least in 2024, the greatest variety and diversity. Maybe it’s because it takes less money to write a book than to make a film or assemble a reissue, though it’s not so easy to find a publisher and distribution. So there’s an enormous range of artists covered, certainly in terms of their fame, from the Beach Boys to cult rockers for whom a full-length book would have been unimaginable during their lifetime, like Skip Spence.

But there’s also a big spectrum of approaches used. In this list, we have biographies, memoirs by musicians, a memoir by a wife of a star, a memoir by a rock journalist, very detailed reference books of reviews and discographies, oral histories, and rock photo books. Some volumes sort of combine different approaches, like the very good one by two members of a group that didn’t make any records or much of a commercial impact, the Liverbirds. Many of them, unfortunately, won’t gain a big audience because they’re not about stars, including the #1 pick, though the short-lived group it documents did have a #1 hit in the UK.

1. Hollywood Dream: The Thunderclap Newman Story, by Mark Wilkerson (Third Man). If they’re remembered at all today, Thunderclap Newman—a group, not a guy—are usually only known for their 1969 hit “Something in the Air,” a #1 single in the UK, and a Top Forty entry in the US. They did make an album and have a few non-LP sides, but that might seem like slim pickings for constructing a 400-page biography. That’s not the case, in part because all three of the principals who formed Thunderclap Newman—singer/songwriter Speedy Keen, teenage guitarist Jimmy McCulloch (most known for his 1970s stint in Wings), and pianist Andy “Thunderclap” Newman—had interesting, quirky stories. The point’s often been made elsewhere, but this was about the most unusual combination of talent assembled for a notable 1960s rock act. On top of this, Pete Townshend was almost a fourth member, producing their album and playing bass on it.

Considering all three main members are dead, Wilkerson did a remarkable job with his research. He found and interviewed numerous key associates, not least among them Townshend. He did interview Newman before the pianist’s death, and also had access to unpublished Keen memoirs, as well digging up many period quotes from everyone. The pre- and (less interestingly) post-Newman careers of all three are covered, including McCulloch’s stint as a young teenager in One in a Million, and later times in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, Stone the Crows, and Wings, among other acts. So is Keen’s contribution of his composition “Armenia City in the Sky” to The Who Sell Out and his longtime friendship with Townshend (and skimpy solo career), along with how Newman made his first impression on the Who guitarist as an eccentric jazz pianist when Pete was still an art school student.

Besides discussing, naturally, “Something in the Air,” Wilkerson also thoroughly documents the protracted creation of their only album, Hollywood Dream. Part of the reason Thunderclap Newman were short-lived is that—in what must have seemed unfathomable at the time—there was a gap of about a year between the debut single “Something in the Air” and their next single, and more than a year between “Something in the Air” and their album. Also, they weren’t accomplished as a live act, failing to put together many effective appearances to promote themselves before disbanding. A related problem was that although they could combine their disparate talents with Townshend’s guidance, they were really too different personally and musically to be able to communicate well between themselves. Wilkerson deftly weaves together stories that are in some ways difficult to connect, and pays substantial attention to the odd and hard-to-categorize music they did manage to record, though the section on Andy Newman’s final decades might be longer than it merits.

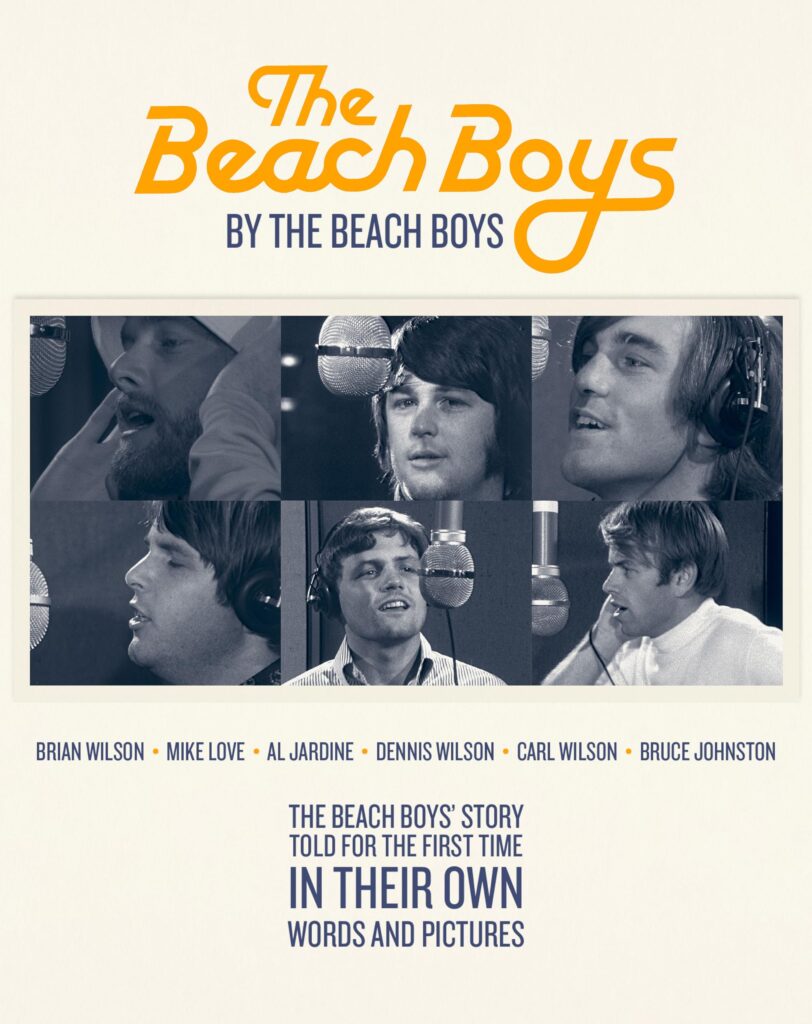

2. The Beach Boys By the Beach Boys, by the Beach Boys (Genesis). In the spirit of the Beatles’ Anthology book, and several others in which group members tell their story in a volume with an oral history format, quotes from the Beach Boys (and a few others) cover their history here. It’s not quite up to the level of the Beatles’ Anthology in depth, visuals, and candor, but it’s still pretty interesting, even if you know a lot about the group and some of the stories are inevitably familiar. Fortunately, it cuts off at 1980, eliminating the lengthy later period in which they only sporadically put out music, and usually had more headlines for in-fighting and sad/tragic incidents. There’s a lot of depth to the coverage going way back to their first records and even earlier, and while most of the quotes are by the six principal Beach Boys (Brian Wilson, Carl Wilson, Dennis Wilson, Mike Love, Al Jardine, and Bruce Johnston), there’s room for a few by guys who passed through the official lineup fairly briefly, those being David Marks, Blondie Chaplin, and Ricky Fataar. There are tons of pictures too, again running the gamut from familiar to rare, and some non-photo memorabilia, including Brian Wilson notebook lyrics to a song that’s titled “Surfer Girl” but seems entirely different from the hit of that name.

If you’re looking for weaknesses, these aren’t too significant, but a number of controversies are not mentioned or referred to only briefly. Those include their father Murry Wilson getting fired as manager, and selling their publishing for a sum far below what it was ultimately worth; full details of Brian’s nervous breakdown of sorts on tour in late 1964, which led to his near-withdrawal from live performance; Mike Love’s disputes with Van Dyke Parks over lyrics for Smile; and, not too surprisingly, Dennis’s involvement, which was more than fleeting, with the Manson Family. While opinions sharply differ on the quality of the group’s post-Smile music, from my viewpoint it went steadily downhill, and some of the sections on their 1970s work can be as tough going as it is to listen to their records from that period. And while most of the quotes are from the Beach Boys and a few of their peers, there are also some from much later acts that don’t add insights of note, like the Reid brothers from Jesus & Mary Chain and Rufus Wainwright. Some actual associates who could have added a few perspectives worth reading aren’t heard from, like Van Dyke Parks or session musician Carol Kaye.

Of course similar criticisms could be applied to other rock oral histories. The Beatles’ Anthology, for instance, didn’t include quotes from Pete Best, engineer Geoff Emerick, Allen Klein, or Yoko Ono. For those who want those other perspectives and coverage of the controversies, they’re detailed fairly extensively in some other books. This is still a good read – for the most part and mostly through the early ‘70s, anyway – and does focus on the music, the truly important foundation of the Beach Boys’ legacy.

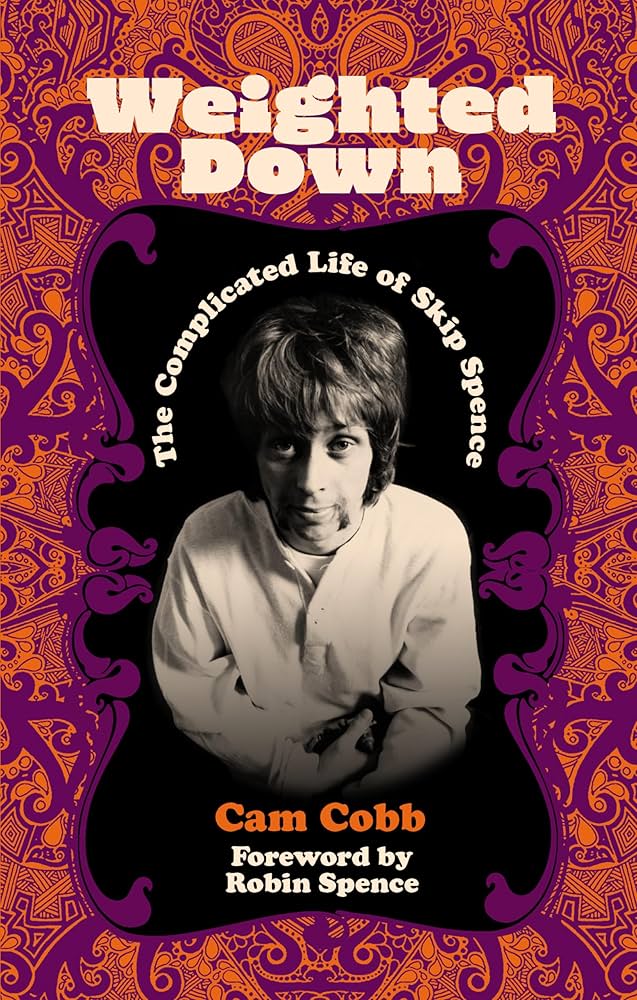

3. Weighted Down: The Complicated Life of Skip Spence, by Cam Cobb (Omnibus Press). Singer-songwriter-guitarist (and sometime drummer) Spence was an important part of Moby Grape; drummer and occasional songwriter in early Jefferson Airplane; and auteur of one of the best and most haunting psychedelic folk albums, 1969’s Oar. That still might seem a slim resume to base a 375-page book on, but this is a good thoroughly researched biography that’s not unduly padded. The author interviewed quite a few people who worked with or knew Spence well, including several from Moby Grape; Jefferson Airplane guitarist Jorma Kaukonen; and several close family members, including Skip’s first wife. While much of Spence’s story has been told before, for those who are cult enthusiasts of his work—and I’m one—there’s a lot of new detail here, down to meticulous recaps of most of the known live shows he played, and some obscure acts he was part of before being whimsically recruited as the Airplane’s drummer. His ebullient personality and complex, eclectic songwriting (especially on Oar) is celebrated by his associates, and Oar’s mixture of rock, blues, country, folk, psychedelia, and goofball humor gets the most critical description. But his extensive mental problems are also delineated, though these didn’t seem to surface with a vengeance until the oft-told incident when he briefly took up with a mysterious woman when Moby Grape were recording in New York in mid-1968.

As to how Spence could descend into such a mentally and soon materially troubled life in his early twenties, that’s probably impossible to determine, especially as he’d seemed so musically together. And, if not exactly a paragon of stability, more personally together than his image might have you believe, having served in the Navy as a teenager without incident and then started, perhaps at too young an age, a family. His three decades or so in and out of hospitals, and on and off the streets, got generally worse as time went on. They’re not the main focus of the book (though much of it’s described in the last hundred or so pages), however, and though his sporadic attempts at post-‘60s music-making are also part of the story, they aren’t the dominant ones. Some stories that are part of the Spence legend are clarified along the way; he didn’t ride a motorcycle right from Bellevue hospital to Nashville to record Oar, for instance. The volume also includes an extensive gigography and sessionography.

4. Long Agos and Worlds Apart: The Definitive Small Faces Biography, by Sean Egan (Equinox). That’s not a typo in the title; it has the word “agos” in plural. Although this isn’t the only book on the Small Faces or their individual members, it is the most thorough one on the band’s career. Egan interviewed keyboardist Ian McLagan, drummer Kenney Jones, and even McLagan’s predecessor Jimmy Winston, who was in the group for their first couple singles; obviously he interviewed McLagan before McLagan’s death in 2014. Singer/guitarist Steve Marriott and bassist (and co-writer of much of their original material with Marriott) Ronnie Lane are extensively represented by archive quotes. Just as impressively, a good number of associates who aren’t always often heard from were also interviewed, including Pete Townshend, Marriott’s first wife, early manager Don Arden’s son David, Andrew Oldham, and Humble Pie drummer Jerry Shirley.

Of most importance, Egan tells their exciting, complex, and sometimes sad tale well, and not just through reflecting their complementary and at times clashing personalities. He describes all of their records in depth, including not only tracks from their hit singles and principal three LPs, but also B-sides and numerous cuts that only showed up on compilations. Although a big and enthusiastic fan for the most part, as in his other books, he doesn’t shy away from criticizing songs and production when merited. This isn’t at the expense of the core story, in which four very young musicians rose to fame very quickly, and went through wrenching management changes and financial shenanigans in a career that only lasted about four years. So is their somewhat mystifying failure to tour the US, attributable in part but not whole to a drug bust of McLagan, especially after “Itchycoo Park” had given them their sole US hit.

The impression’s given, by both the author and some of the band comments, that in retrospect the band should have stayed together longer, even though everyone went on to bigger global success with the Faces and Humble Pie. But maybe they weren’t destined to last considering widening differences between Marriott and Lane in particular, or patchy money matters that found them short of funds even after their 1968 album Ogdens Nut Gone Flake topped the UK charts. The group’s strange petering out in late 1968 and early 1969 with sessions backing French star Johnny Hallyday and anticlimactic commitment-filling gigs is covered, as is to some degree their subsequent careers (see Egan’s book on Rod Stewart’s early career for more on the Faces).

Those final sections inevitably lack the interest of the material on the 1960s, and Egan could have detailed the recent archive release of two fiery Belgian shows in early 1966 more extensively (though it’s mentioned). There might be more detail on the group’s financial mishaps and managerial conflicts than some might like, though these aren’t overdone. And there are other worthwhile details in the books Small Faces: The Young Mods’ Forgotten Story and the day-by-day The Small Faces Quite Naturally, as well as Jones’s memoir and the recent Marriott bio All or Nothing. However, this is the most complete and well-rounded volume on a band that’s proved more long-lasting, influential, and internationally beloved than anyone would have predicted when they disbanded, and considering their very limited ’60s success in the US.

5. The Other Fab Four: The Remarkable True Story of the Liverbirds, Britain’s First Female Rock Band, by Mary McGlory and Sylvia Saunders (Grand Central). The co-authors were both in the Liverbirds, the all-women Liverpool quartet who played extensively for about four years in the mid-1960s. They weren’t too familiar to English-speaking audiences, as they played mostly in Germany, and there often at Hamburg’s Star-Club, for whose record label they made a couple LPs and some singles. McGlory and Saunders alternate the writing of different chapters, an approach that in other books can be awkward, but works pretty smoothly here. It’s an interesting tale that’s not like the usual memoir of rockers that didn’t make it big, in part but not only because they faced the unusual task (and sometimes obstacles) of being one of the few all-women bands who played their own instruments who were around in that era. They also had interactions, if sometimes fleeting, with many of the big names of the times, including the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Kinks, and Brian Epstein. There are also insight into the rewards and challenges of making a career in Germany, and behind-the-scenes stories of how the famed Hamburg rock scene worked, as well as life in the red light district where the acts played.

While their music and records are not neglected, these were not as interesting as their story, being dominated by cover versions and boasting an unpolished feel that put them more on the level of an average British group of the time than musical innovators. Opportunities to be managed by Epstein or Kinks manager Larry Page before they relocated to Hamburg weren’t followed up on, and they didn’t play in the UK much after that, and never made it to the US, where they’re still little known. Although the authors don’t have regrets about concentrating on the German market, it’s a little surprising that they don’t have many if any regrets about not making inroads elsewhere. While they take pride in the few original songs they recorded, all written by guitarist Pam Birch, there’s also not much of a sense of trying to forge a more original sound based on their own material. That almost certainly would have made them passé by the end of the 1960s had they not broken up before then due to marriages and other obligations, including guitarist Val Gell becoming a caretaker for a boyfriend who became disabled. They had to do a 1968 Japanese tour without Gell or drummer Saunders, which pretty much ended the group. While the authors went on to pretty stable lives dotted by periodic Liverbirds reunions, Birch and Gell weren’t as fortunate, and their spells with poverty and physical/substance issues are detailed in some of the final chapters.

6. MC5: An Oral Biography of Rock’s Most Revolutionary Band, by Brad Tolinski, Jaan Uhelszki, and Ben Edmonds (Hachette). Based on interviews done over a series of years by the late Ben Edmonds, this has quotes of varying length—sometimes very extensive—by all of the MC5 except Fred Smith, as well as close associates like manager John Sinclair, manager/producer Jon Landau, A&R man Danny Fields, promoter Russ Gibb, and a few wives/girlfriends of the band. Linking text by the two other authors sets the basic scene of the group’s origins, ascent, and downfall. This is pretty interesting throughout, in part because the band’s career was so unusual in their affiliation with political activists and incendiary performances, in addition to their pre-punk-metal-ish hard rock music. There’s far more attention paid to the Sinclair era, which encompassed their first and by far most famous album, than the few years (and two albums) after Sinclair was jailed and the band cut their ties with him, though the early ‘70s do get some space.

As expected if you come into this with a decent knowledge of the MC5’s history, there are often quite different accounts and perspectives on the same incidents. As just one example, guitarist Wayne Kramer expresses his displeasure with Kick Out the Jams at length, claiming “nobody liked it.” In the very next quote, Sinclair states, “You couldn’t have a more accurate representation of how the band sounded.” The band’s descent and dissolution, at least in retrospect and especially reading through these memories, was unsurprising given the tensions between their revolutionary zeal and hunger for national success; spontaneity and the professionalism required to make records that might sell and get on the radio; and Sinclair’s communal/political ethos and the musicians’ eventual desire for greater individual and economic freedom.

It’s a little surprising, for me anyway, to read a fair amount of criticism of singer Rob Tyner on various grounds – not moving around enough on stage, not being as committed as some of the others in some respects, and other matters that can seem a little picky, considering how vital he was to the group’s music. Note that while much of the MC5 story’s told here, Kramer and bassist Michael Davis’s memoirs, as well as Leni Sinclair’s Motor City Underground, are also worth reading for those who want more. Also note that while Elektra Records comes off badly for dropping the MC5 after they caused headaches at a violence-strewn Fillmore East concert and a major Detroit retailer stopped distributing Elektra product when the group took out a profane ad against the store, the book doesn’t give Elektra’s different side of the story. That’s in Elektra head Jac Holzman’s memoir Follow the Music, which also has comments, some quite negative, from Kick Out the Jams co-producer Bruce Botnick.

As one relatively minor point for me to pick on, a couple MC5ers and John Sinclair dump on Big Brother & the Holding Company, Tyner saying they “had no rhythm section. There was no drive,” and Sinclair claiming “we killed Big Brother & the Holding Company” when the MC5 opened for them. On a recent Record Store Day release of Big Brother at one of the shows the MC5 opened for them (on March 2, 1968) at Detroit’s Grande Ballroom, Big Brother sound very good. It’s impossible to verify whether they were killed by the MC5 without a tape of the MC5 set, but certainly the audience responds enthusiastically to Big Brother, if perhaps not with over-the-top wildness.

7. Just Backdated: Melody Maker: Seven Years in the Seventies, by Chris Charlesworth (Spenwood). From 1970 to 1977, Chris Charlesworth was a staff member of the British weekly pop music paper Melody Maker. For about half of that time, he was the magazine’s New York correspondent, actually living in the city as a base for interviewing musicians from both sides of the Atlantic and writing stories that might not have been too easy to get in the UK in pre-Internet days. Charlesworth wrote about, interviewed, and sometimes hung out with and befriended many musicians, from the ex-Beatles, the Who, and Led Zeppelin down to pre-stardom CBGB figures like Patti Smith and Blondie.

This is a good memoir of those years that balances purely musical memories with much of the colorful fun and games the acts got up to, on tour and otherwise (and in which Charlesworth not infrequently participated). There are numerous quotes from stories and concert/record reviews he wrote for Melody Maker, but not so many that they interfere with an overall storytelling flow. While some of the accounts are straightforwardly devoted to the musical side of things, sometimes they relay behind-the-scenes incidents that didn’t make it into print at the time and might embarrass some big names, or, in the case of John Bonham drunkenly assaulting a flight attendant, cause much worse than mere embarrassment. If few of the acts come across poorly and the author became chummy with some of them (especially Keith Moon), some of the stars he spoke with acted very disagreeably, especially Sly Stone (taking his wife-to-be into an adjoining room during an actual interview for a sex break) and a haughty Neil Diamond.

What’s most striking about Charlesworth’s experiences is how easier it was for a young, not-so-veteran rock critic to get access to big stars in those days, sometimes just by ringing up personal telephone numbers willingly volunteered to him by the acts themselves. Also surprising, at least at this distance, is how big a bill record companies and publicists footed for flying around journalists to write about their clients, and sometimes do more than just the writing. This might have crossed some ethical lines in how labels and PR staff probably expected good bulky coverage in return, something the author periodically acknowledges, though without too much anguish, especially considering how much fun he was having, whether at their expense or not. If stories about some of the aforementioned artists and other big names like David Bowie might be the biggest attractions, it’s also remarkable how much stylistic range a staff writer like Charlesworth had to document as part of his job. These weren’t just the big stars and hip underground names, but the ones that time has not respected, like Black Oak Arkansas, though he dutifully did his job and wrote what he was required to file.

8. Drums and Demons: The Tragic Journey of Jim Gordon, by Joel Selvin (Diversion). Jim Gordon was one of the top rock drummers of the 1960s and 1970s, though he’s about as well known for murdering his mother in the early 1980s. So this biography is in some ways a tough one to read, but it’s sensitively balanced between appreciation of his talents and documentation of his mental illness. Gordon might be most known to general rock fans as drummer in Derek and the Dominos, but he played on tons of hit records by many artists, as well as on many virtually unknown discs (and jingles and TV themes). Serving an on-the-road apprenticeship with the Everly Brothers as a teenager, he also played live with acts ranging from Paul Anka to Jackson Browne. Selvin details his contributions to hits like Carly Simon’s “You’re So Vain” meticulously but readably, which involved not just top technique, but also imaginative use of many parts of his kit. There are also stories of how he worked in the Dominos, including his contribution as a songwriter to “Layla,” though one of his numerous girlfriends, singer Rita Coolidge, was also involved in constructing the long piano-led tag and didn’t get a credit.

Gordon didn’t show many obvious signs of mental illness for his first decade or so as a professional, with the vital exceptions of episodes in which he attacked Coolidge and his second wife. His descent into schizophrenia was painful, enhanced by substance abuse. He continued to play drums, though by the 1980s his reputation had lowered to the point where he was part of a bar band. By that time voices he was hearing in his head had gotten to the point where he repeatedly moved his gold records and drums back and forth to the dumpster where he lived. His subsequent lifetime prison stint isn’t detailed in much more than epilogue fashion, appropriately as what he did before of much greater interest and significance.

9. Shapes of Things: From the Yardbirds to Yusuf with Paul Samwell-Smith, interviews with David French (self-published). Since this book is pretty short, running about 100 pages, and almost all Q&A interviews with one person, its audience will be limited. That’s fine—if you’re a Yardbirds fan, it’s well worth reading, since these are the most extensive recollections their bassist ever gave. Samwell-Smith also produced the first Renaissance album (when they were led by ex-Yardbirds singer Keith Relf and ex-Yardbirds drummer Jim McCarty) and, more famously, Cat Stevens’s big albums and Carly Simon’s Anticipation. About half the book discusses his time in the Yardbirds (in which he often also acted as producer); the other half his early years as a producer, in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

There’s not much controversy here, unless you want to count his brief affair with Simon—just a lot of detail about records in which he was involved, as well as the Yardbirds’ performances and career. Samwell-Smith was more important than many fans realized to the Yardbirds as an innovative, propulsive bassist and producer (though he was sometimes credited as “musical director” rather than producer), and has a lot of interesting things to say about their discs and their dynamics, with both Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck. Maybe the sections on Stevens aka Yusuf and Simon are of less interest to Yardbirds fanatics, but they’re worthwhile for their perspectives on record production, which are clear and balanced, as are his perspectives on the Yardbirds.

The interviewer/author, David French, also did a good recent biography of Relf, Heart Full of Soul. Combined with McCarty’s good memoir from a few years before that, these add up to a decent biography of the Yardbirds, though spread across a few sources.

10. Phil Ochs On Track: Every Album, Every Song, by Opher Goodwin (Sonicbond). This is one of the more valuable volumes of Sonicband’s very extensive series going through the discography of notable artists. In part that’s because Ochs, unlike some of the other performers featured in the series, wasn’t a big star, and there’s no other book to my knowledge that goes into his catalog in depth. This follows the On Track format of detailed description, and some critical analysis, of all of Ochs’s material. More attention is paid to the lyrics than the music, but the music isn’t ignored, either in the melodies or the arrangements, which evolved considerably from the plain acoustic accompaniment of his early albums. Goodwin also gives a lot of context for the political and social events that inspired many of the songs. While this can be overdone or extraneous in many books, in Ochs’s case it’s both extremely relevant and pretty interesting, as his writing was more directly inspired by and about contemporary events and situations than perhaps any other significant performer of his time.

Although not every Ochs fan will share this view, one of the book’s primary assets is how it gives a lot of straight detail about his many releases that include tracks that weren’t featured on his primary LPs. There were a lot of these, including non-LP singles, items that only showed up on compilations, and numerous posthumous releases of live recordings, outtakes, and demos. It’s a pretty complicated discography for someone who didn’t have hit records, and I’ve long wished something of the sort would be compiled to make it clear what came out where. And this material is hardly of interest only to collectors; while overall not as strong or important as his full-length studio albums, they include some very fine songs and performances, and many compositions that weren’t released while he was alive. Justifiably, the songs on his Elektra and A&M albums get the most text, but enough info is given on the rest of his work to give you a good idea of what’s out there. That includes bootlegs, of which there were many more than I suspected.

11. Jimi Hendrix: The Day I Was There, by Richard Houghton (Spenwood). Part of a series of collections of stories and memories by those who were there at the concerts of major performers, this assembles plenty of them from people who saw Hendrix between 1965 and 1970. That might sound like a marginal contribution to Hendrix literature, but at 476 pages, it’s hardly insubstantial. Too, those quoted range from the very most famous Hendrix fans, including Paul McCartney, to accounts collected by many just plain fans specifically for this volume. There are some contributions by relative insiders who actually worked with Hendrix at some capacity, if only for one specific concert. The majority, however, are concertgoers whose interactions with Jimi were just as members of the audience. Inevitably there’s much repetition of basic points as to how brilliant and life-changing he was, as well as some overly self-consciously poetic prose about his unearthly significance. But there are some pretty interesting stories and perspectives here too, as well as some unusual incidents that don’t get reported in the usual Hendrix biography. Sometimes onlookers at the same concert directly contradict each other as to what happened, as might be expected when trying to recall what took place about half a century later.

A few things that are striking when reading these in such bulk is how young Hendrix’s audience usually was – often teenaged or barely teenaged, and seldom as old as Jimi himself was. Also how much easier it was to get pretty close to the stage with superstars then, and not infrequently manage to get a word with Jimi or members of his band, or retrieve a piece of his equipment, or sometimes (though not too often) even party with Jimi and the Experience after the show. Famous concerts like the Monterey, Woodstock, and Isle of Wight festivals are documented, but most of the entries are for less celebrated venues as he built his following in the UK and then criss-crossed the US. Interwoven with descriptions of Hendrix are oft-amusing recollections of how much quirky planning it took to attend a concert if you were very young back then, with plenty of rides from parents, or lies to parents that were necessary to sneak out. Sometimes these dominate the accounts, but the music isn’t overlooked, with some vivid descriptions, when the participants have clear memories, of specific songs, guitar burnings, Mitch Mitchell drumming, and opening acts like the Soft Machine and Cat Mother. It also seems like Hendrix played “The Star Spangled Banner” at quite a few shows before his famous Woodstock version.

12. Pressing News: British Music As It Happened 1962-1972, by Richard Morton Jack (Lansdowne). This is the kind of book whose interest is pretty limited to intense historians/collectors/fanatics, and that you use for reference rather than reading all at once, or even in its entirety. That doesn’t mean it isn’t valuable, of course, built around reproductions of more than a hundred press releases for British rock artists between the early 1960s and early 1970s. Usually the releases are tied to specific records, from the most famous (Sgt. Pepper) to some by very obscure acts (Fresh Maggots, Jerusalem, and the Pete Best Four, to name just a few examples). These are accompanied by quite a few reprints of reviews, and sometimes full stories, that appeared about these records and acts at the time, not years later, when critical views about the performers and their importance often shifted. There are also reproductions of some ads from the period, and each entry has a substantial paragraph from the author explaining the context of the material and the performers’ career at the time.

A little disappointingly—and this has nothing to do with the talent of the author and the usual fine design he brings to his specialized books—the releases themselves (and the reviews) are often bland and basic, if reflective of how the industry promoted rock at the time. There aren’t a ton of genuine surprises, though it’s a great service to have reviews from UK music papers reprinted, as (except for Melody Maker, and to extent NME) accessing the ones from British weeklies is difficult, even for the major Disc and Record Mirror publications. Morton Jack also dug up quite a few items from general interest/regional newspapers and magazines that have seldom been seen since their publications, going back to a few (such as a review in the Newtown & Earlestown Guardian) in the book’s first entry, on the Beatles’ “Love Me Do” single. Almost all of the reviews and stories, incidentally, are sourced from UK publications, though a very few from the US are present.

There are some surprising nuggets here and there for British rock obsessives. Not everyone cares about such things, but it was interesting to read, for instance, a quote from the Zombies’ road manager hailing their cover of “Sticks and Stones” as the best track on their debut LP; Marc Bolan quoted as calling the Who’s debut album “a bad LP”; or that the Move’s debut LP was originally intended for November 1966 (it didn’t appear until 1968) and was to be titled Move Mass. While it’s unlikely every reader wants to go through the clippings and releases for all of the selections depending on their taste (especially the more esoteric ones from the late 1960s and early 1970s), there’s something for every fan of British rock of the period here, from the superstars to worthy cult acts like Blossom Toes.

13. Gettin’ Kinda Itchie: The Groups That Made the Mamas & the Papas, by Richard Campbell (www.gettinkindaitchie.com). Before the Mamas & the Papas were formed, all four members did quite a bit of time, and (except for Michelle Phillips) made a good number of records, as parts of primarily folk-oriented groups, going back to the mid-1950s. These included, for John Phillips, the Smoothies, the Journeymen, and the New Journeymen; for Denny Doherty, the Halifax Three, the Mugwumps, and the New Journeymen; for Cass Elliot, the Big Three and the Mugwumps; and for Michelle Phillips, the New Journeymen. All of these roots, and routes to the Mamas & the Papas, are thoroughly explored and documented in this self-published volume. It’s well above the standards of the usual self-published book, both in its design, with many photos and reproductions of vintage ads and record sleeves, and the writing, by a Mamas & the Papas authority who’s written about them and their pre-Mamas & the Papas groups extensively for many years.

It’s true this part of the story, and the music that was made by these acts, isn’t as interesting as the Mamas & the Papas’ story (brief as their career was). It’s also true that for general Mamas & the Papas fans, the essentials might be satisfactorily covered in the recent (and best) Mamas & the Papas biography, Scott G. Shea’s All the Leaves Are Brown: How the Mamas & the Papas Came Together and Broke Apart. But the level of detail here is impressive, down to descriptions of the jingles and commercials — quite a few, actually — recorded for the likes of beer companies by the Journeymen and the Big Three. Much of the information was gleaned from first-hand interviews, not only of musicians in the groups, but also of many of their associates, including some with surprising resumes, like Journeyman-for-a-while Marshall Brickman, who went on to fame as a screenwriter (mostly famously for Annie Hall). There’s even an appendix laying out all of these group’s known concerts, TV/radio appearances, records, and recording sessions, which are more extensive than almost anyone would suspect.

14. King Mod: The Story of Peter Meaden, The Who, and the Birth of a British Subculture, by Steve Turner (Red Planet). Peter Meaden managed the Who for a while around mid-1964, though the nature of his management, how official it was, and how long it lasted has been reported in various ways. Steve Turner interviewed Meaden in 1975, a few years before Meaden died, and it was the most extensive interview he ever gave. That interview, parts of which were printed in a few outlets in the past, is reprinted in its entirety here, taking up almost a third of this 275-page book.

But more of the book’s devoted to a general biography of Meaden, who was most celebrated for his association with the Who, but also managed some other acts, was involved in other aspects of the music business, and did a lot to help establish the mod movement. There’s about as much attention paid to the fashion and lifestyle side of mod and Meaden as the music, since he was one of the pacesetters in setting mod trends in London. But there’s also, in addition to the expected coverage of how he was vital to injecting mod sensibilities into the Who, interesting text on his management of the British soul act Jimmy James and the Vagabonds; his brief work promoting, rather ineptly, Captain Beefheart’s first trip to the UK; his erratic collaboration with a young Andrew Oldham, who quickly outpaced Meaden as a mover and shaker in the British music business owing to his greater business savvy; and his brief resurrection of sorts working with Steve Gibbons in the mid-‘70s.

Besides his interview with Meaden, Turner also draws upon comments from people who knew Peter. It’s a quicker read than you might expect, since there are a lot of full-page photos of Meaden and interesting people on the mod scene, including good ones of the 1964 Who. That’s okay, however, as the photos are themselves quite good and interesting, with informative captions.

The full-length Meaden interview isn’t as interesting as I hoped. It’s quite repetitious, and he seemed more intent on making general rather hyper observations on the hedonistic mod lifestyle as the music associated with it. The most interesting part, naturally, is when he does get around to discussing the Who, though he seems to view his contribution to their career primarily in influencing their clothes. He also talks about their “I’m the Face”/“Zoot Suit” debut single as the High Numbers, though more in terms of how zealously he promoted it (though it sold very few copies) than how it might have reflected the Who’s creativity. Which it didn’t, very well, in part because both sides were rewrites of American R&B songs with different lyrics (“I’m the Face” of Slim Harpo’s “Got Love If You Want It,” “Zoot Suit” of the Dynamics’ “Misery”). Meaden misremembered the Showmen’s “Country Fool” as the source for “Zoot Suit,” a mistake which got repeated numerous times in Who biographies and other rock history literature. He expresses no regret or acknowledgement about taking the songwriting credits for these blatant rewrites, which might not have been on the up-and-up.

Although a key part of the mod movement and (if only in passing) the Who’s early career, Meaden wasn’t organized or visionary enough to compete on the same level as managers like Oldham or the Who’s Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp, getting paid 500 pounds to relinquish his involvement with the band by the band’s new and more ambitious managers. A couple comments in the book reflect Meaden’s colorful inability to fully optimize his genuine enthusiasm for mod and music. The jacket he bought for Roger Daltrey, as seen in promotional material for the High Numbers single, “was the high point of my career, you might say,” he notes in his interview with Turner. In a report made by immigration officials when Captain Beefheart and his band were denied entry to the UK for lack of work permits, “Mr. Meaden then pleaded for clemency on the grounds of his own stupidity, a plea which was rejected.”

It’s not too important, but if you’re on the lookout for embarrassing mistakes, Roger Daltrey’s last name is misspelled as “Daltry” in one caption—a 1966-level goof that doesn’t belong in a 2024 book. It’s also odd it’s mentioned that Meaden and Oldham were involved with the Moments, Steve Marriott’s pre-Small Faces group, which is not mentioned in the most thorough Small Faces biography, Sean Egan’s recent Long Agos and Worlds Apart: The Definitive Small Faces Biography (also reviewed in this post).

15. The Dave Clark Five: Bits & Pieces! Every Song from Every Session, 1962-1973, by Peter Checksfield (www.peterchecksfield.com). Like Checksfield’s books for the Searchers, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Tremeloes, this lists and describes every release by the book’s featured act, the Dave Clark Five. Maybe some people feel they weren’t good or important enough to merit such intense documentation, but for all their success, no one’s done such a thing before. And for all the uneven quality of their output, they did make a good number of good records, not limited to the numerous hits that, to quote a title of two (!) entirely different hits of the same name they had, “Everybody Knows.” Everything from their dozen or so years is here, from their obscure (and mediocre) 1962 singles through their plethora of US-only albums, their little known early ‘70s releases (including those credited to Dave Clark & Friends), and even a good number of unreleased or download-only tracks. Checksfield’s assessment of these is, in keeping with his other volumes, pretty generous. But the sound of each them is described, and for all their fame, you’d be surprised how little pure description is given to the band’s catalog in rock literature, aside from their big hits.

While there weren’t a ton of oddities in the group’s large discography, some that even DC5 collectors might have missed are noted, like the full original version of “’Til the Right One Comes Along” (the piano solo is edited out of the version on the History of the Dave Clark Five CD compilation). There’s also a very comprehensive listing of their many TV (and occasional film) appearances, for which they seldom managed to actually play live instead of to the record; many picture sleeves of LPs and 45s, some of them rare non-US/UK releases; some sheet music repros; and some stills from their TV/film spots, although all of the illustrations are in black and white. It is striking, though not previously unknown, how many more DC5 records came out in the US than in their native UK; Epic Records really squeezed out what they could in the group’s 1964-67 prime. It’s also striking how the label went all-out for picture sleeves on their US 45s, all the way through the end of the ‘60s, though their last big American hit was in 1967.

Note that this book become unavailable as a print version shortly after its release in that format. The text, without the images in the print version, can be accessed at https://peterchecksfield.com/the-dave-clark-five-bits-pieces/.

16. Labyrinth: British Jazz on Record 1960-75, by Richard Morton Jack (Landsdowne). British jazz from this era is not a specialty of mine, and I daresay not a specialty of too many people, even in the UK, and less so elsewhere. However, this is an exceptionally well produced record guide to many—I would venture most—of the British jazz LPs made between 1960 and 1975. It’s not just a discography listing catalog numbers and dates; each of the several hundred albums gets a fully considered paragraph-long review by the author. Many of the entries also print excerpts from reviews of the albums actually printed around the time of their release, along with full-page reproductions of the front and back covers and inner labels. There’s also a very interesting and lengthy introduction by musician and producer Tony Reeves, who was part of and worked with several acts during this period, most famously Colosseum. There are also a few pages reproducing ads of the time for British jazz releases.

Even within the world of jazz enthusiasts and collectors, British jazz doesn’t get a ton of attention, and many of the names will be unfamiliar to readers as few made an international impact. The ones that did tended to be ones whose impact bled over to the rock audience, like Jack Bruce, John McLaughlin, Chris Spedding, Colosseum (though only their first LP is included), Harold McNair (via his work with Donovan), John Cameron (also as a Donovan associate), Hugh Hopper (with Soft Machine), Elton Dean (part of Soft Machine for a while), Henry Lowther (part of Manfred Mann and John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers for a while), and others. Morton Jack covered some British rock with a jazz influence in the massive British rock guide he edited and wrote many reviews for, Galactic Ramble, and rock albums by the many acts with players with jazz experience are usually detailed in there.

This is the place to learn about names known more to jazz aficionados, like Joe Harriott, Mike Westbrook, Norma Winstone, Michael Gibbs, and Nucleus, though one (Dudley Moore) is extremely famous, though not principally for his accomplished jazz piano. It also offers insight into some styles that were more prevalent in British jazz than elsewhere, like Indo-Jazz. This volume would rank higher on my list if I was more heavily interested in the subject; its modest ranking is not a reflection of the high quality of the writing and graphics. (My interview with the author of this book is at http://www.richieunterberger.com/wordpress/british-jazz-1960-1975-author-richard-morton-jack-talks-about-his-definitive-guide-labyrinth/.)

17. Magical Highs – Alvin Lee & Me: A Sixties Woodstock Memoir, by Loraine Burgon (Spenwood). The author was Alvin Lee’s partner for about a decade from the early 1960s through the early 1970s, and while they didn’t marry, she was there for his rise from Nottingham cover bands to stardom with Ten Years After. This is above average for a partner memoir, as it’s pretty detailed and well written, and—in a less common virtue—often attentive to the music, with plenty of accounts of concerts, recordings, and Lee’s evolution as a guitarist, songwriter, and singer. Sometimes there’s too much space given to non-musical aspects of their lives, like how their homes were set up and drug use. But although the pair separated in 1973, her love for Lee and his music is clear—indeed, she never did seem to stop loving him, though she might have realized they weren’t ultimately suited for the long haul.

Considering how tight they were for a pretty long period, their relationship unraveled fairly quickly over the course of about a year when they moved to large home (actually their second large home) outside of London, with both getting caught up in extramarital affairs and Lee’s attention getting distracted by some drugs and interlopers. This included a very brief fling between Burgon and George Harrison, whose delights in earthly pleasures contrast with his holier image as a devout follower of Indian religion, and doesn’t come off as well as he usually does in rock histories. After leaving Lee, Burgon was involved with Traffic’s Jim Capaldi for a couple years, and then caught up in a zealous bust of Ronnie Wood’s home with Wood’s then-wife (both were found innocent after a couple trials). That’s where the story ends and while those post-Lee adventures are covered in satisfactory depth, most of the book’s given to her journey with Lee, also documenting their pot and LSD use with unusual positivity for a rock memoir. As Lee himself didn’t write an autobiography, this is as close as we might come to a Ten Years After history, so close-up is the account.

18. Dreams: The Many Lives of Fleetwood Mac, by Mark Blake (Pegasus). This is unusually structured for a biography, or a sort of biography. Instead of going through the history of the band from beginning to end, the 400-page book is divided into a little more than 100 short chapters, each dwelling on a pretty particular aspect of the group and their career. These progress in roughly chronological order, but not strictly; the overview of Christine McVie’s life, for instance, is the last chapter. The chapter subjects range from profiles, if always brief, of each member (even the ones who passed through very briefly, like original bassist Bob Brunning) and appreciations of individual LPs and singles to very specific ones, like Peter Green’s guitar and their semi-rivalry with the Eagles. There’s a lot of white space at the end of chapters (and sometimes separating sections), so this is quicker to read than most 400-page rock bios.

I was a little skeptical of this approach, but it works pretty well here, since these are told with an eye for interesting and sometimes saucy anecdotes. There are also close-ups of incidents and aspects of Fleetwood Mac that aren’t discussed much, like supermodel Uschi Obermaier’s relationship with the band, or (less interestingly) their influence on early Status Quo. Of course it gets less interesting the more you go past the 1970s, and some of the chapters get into trivia not-so-interesting; it’s not necessary to give a song-by-song account of their 1997 reunion show, for instance. But even if you only read the parts pertaining to eras of Fleetwood Mac that interest you, there’s some interesting stuff here. It’s not satisfying as a comprehensive biography of the band, but it doesn’t intend to be, and you can fill in those details with the many other books about Fleetwood Mac and their individual members.

19. Under a Rock, by Chris Stein (St. Martin’s Press). The Blondie guitarist’s memoir is a rather raw affair in both its content and execution. Stein does cover much of the group’s heyday with some inside detail and droll humor, with even some pretty dramatic incidents discussed in a rather terse fashion, though with enough character and wit to avoid being purely matter-of-fact. Much of the CBGB scene during Blondie’s rise is also recounted. So are his years growing up in New York and his fairly drawn-out path from garage bands and general bohemian lifestyle to meeting Debbie Harry and being a key cog in Blondie’s formation. These are interspersed with a great many non-musical stories, from accounts of his cats to his take on Burning Man, to give just a couple examples. Some of those digressions are interesting and amusing; some of them are not only less so than his musical activities, but at times almost random in their appearance and purpose.

This becomes more apparent in the final sections after his breakup with Harry and Blondie’s split in the 1980, with the last few decades covered in a much more cursory fashion than his pre-1985 years. That’s not such a great loss as almost every reader will be far more interested in Blondie’s prime than their reunions, but the general erratic focus becomes yet less sharp in the last few chapters. A greater focus on the music—the big reason people are interested in Stein—instead of the memories that almost seem like conversational asides would have helped. Still, there are good stories about the composition of some of their most celebrated songs, their studio productions (particularly with producer Mike Chapman, but also their earlier ventures with Richard Gottehrer), their troubled business and management affairs, their success with reggae (including how Stein found the original version of “The Tide Is High”) and disco outings, and their overall unlikely evolution from struggling underground club band to international touring superstars. In combination with Harry’s memoir from a few years back, it fills in a lot of Blondie’s history, though neither book—nor both taken together—are as comprehensive as they could have been.

20. Triggers: A Life in Music, by Glen Matlock with Peter Stoneman (Weldonowen). There’s some material about Matlock’s personal upbringing and life here (if very little about his romantic relationships), but true to its title, this is mostly about his musical career. And an interesting one it is, most famous of course for his time in the Sex Pistols. His years leading up to and including his time as their bassist and frequent songwriter take up more than half the book, and as expected, his rather brief initial stint in the band’s mid-’70s lineup is the most interesting part. The other sections have their value, however, including his more pop-punkish late-’70s group, the Rich Kids; the Sex Pistols’ various reunions; a few solo projects; and tours with Iggy Pop, late-period (very late, quite recent) Blondie, and (briefly) a reunited Faces without Rod Stewart.

It’s an average rock memoir in a good way, meaning the emphasis is on stories of how Matlock met Malcolm McLaren working at McLaren’s King’s Road fashion shop; his time at a prestigious London art school before music became his focus; how the Pistols got together, including their ousting of original member Wally Nightingale, whose handling Matlock regrets; their rise to hit singles and notoriety, and Glen getting replaced by Sid Vicious in early 1977; and the many ups and downs, most work-related but some personal, in the many years since the late-’70s punk explosion. Unlike many such memoirs, however, the author does seem to understand what interests readers most. That means interesting detail about how he wrote or co-wrote songs, including the most famous of these, “Anarchy in the UK,” “God Save the Queen,” and “Pretty Vacant”; how the Sex Pistols worked out arrangements, and went through several studios, labels, and producers as they began recording; and the dynamic, sometimes fractious, between the band members, and between the band and manager McLaren. Matlock takes pains to give his side of the story of leaving the group, particularly that in his view, it wasn’t a commonly cited reason that he liked the Beatles.

It’s relayed in a straightforward likable fashion, not above poking fun at himself, others, and the odd serendipitous circumstances that got the Pistols together and noticed in the first place. Ever since, there were some interesting encounters with other figures like David Bowie, Mick Ronson, and the early Clash. In the more side-note category, he’s refreshingly no-holds-barred in his attack on Brexit and contemporary conservative politics. There is a bad mistake no one else might point out, if a very footnote-like one, when it’s stated Badfinger (whose manager the Pistols met in their early days) had broken up by the time Nilsson covered their song “Without You” for a huge hit in 1971; the most successful lineup of Badfinger in fact stayed together until the mid-’70s. And speaking of the footnotes sprinkled throughout the book, an intriguing one states that “Malcolm once told me that Jamie Reid, the artist who created the Sex Pistols sleeves, was briefl a member of the Moody Blues, but Malcolm said lots of things.”

21. Only You Know & I Know, by Dave Mason with Chris Epting (DTM Entertainment). Still perhaps known more for his stint in Traffic than anything else, Dave Mason subsequently made many solo records, some quite popular. He also made an album as half of a duo with Cass Elliot, was briefly part of Derek & the Dominos, played with Delaney & Bonnie, and was part of the least celebrated lineup (in the mid-1990s) of Fleetwood Mac. All of this is covered in his memoir, which feels a little skimpy, but does have some interesting stories and details. The numerous full pages given over to song lyrics, as well as some generous allocation of white space separating the chapters, means this is a fairly quick read, even at nearly 250 pages.

Even if his in-and-out time in early Traffic wasn’t too long, it and his up-and-down relationship with Stevie Winwood get a decent amount of commentary. Winwood doesn’t have such a controversial public image, so it’s surprising to read how Mason was fired from Traffic in the late 1960s when Stevie told him he didn’t like his songwriting, singing, or playing, though a good share of that is featured on Traffic’s first albums. It was odd at the time that Mason left Traffic after their first album (though he returned after a not-too-long break) and on the verge of their first US tour, and he still seems at something of a loss to fully explain why.

As his very brief time in the Dominos isn’t so well known, and neither is his influence on getting George Harrison interested in playing slide guitar when Harrison briefly toured with Delaney & Bonnie, those are among the more interesting accounts he has to offer. There are also stories of his cross-paths with the likes of Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, and Paul McCartney. The later the years, the more basic and at times cursory the detail, which isn’t a big deal, as it’s his 1960s-1970s prime that interest readers the most.

Like many rock stars, though Mason wasn’t exactly a superstar, he went through his share of drugs, women, marriages, and financial problems. These are all related in a somewhat more casual manner than the usual rock memoir does, though it’s not so off-putting, as he takes a lot of responsibility and blame for his various failures. A specific managerial/financial calamity in the early 1970s is covered so confusingly it seems like text is missing or was poorly edited, as he states “I was living in a near-constant state of vigilance in Canada. Later, too,” without offering more info on how/if/when he ended up in Canada and for how long. And while it doesn’t seem to bother most people as much as it does me, yes, there are some factual mistakes/incorrect chronological sequencing/misspellings that many who are knowledgeable about the 1960s/1970s in particular will catch.

22. Hurricanes of Color: Iconic Rock Photography from the Beatles to Woodstock and Beyond, by Mike Frankel (The Pennsylvania State University Press). As a teenager and young adult in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Mike Frankel took a lot of photos in the late psychedelic era at the Fillmore East, Woodstock, and other venues. As a young teenager, he also got the opportunity to take a lot of pictures at the Beatles’ 1964 concert in Philadelphia’s Conventional Hall, both at their press conference and their stage show. Those pictures are in black and white (and very good for a young photographer who wasn’t professional at that stage), but most of the book is devoted to color shots from a few years later, often using multiple exposures for swirling psychedelic effects.

There are quite a few images of Jefferson Airplane in particular, as Frankel got to know and become quite friendly with them, with some of his shots getting used on covers for the first two Hot Tuna albums. Plenty of other artists are represented, however, including Pink Floyd, the Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, Chuck Berry, B.B. King, Jeff Beck, and Santana, sometimes photographed quite well without psychedelic effects. While most of the pages are occupied by photos and captions, there’s also a considerable amount of text from Frankel describing how he developed his techniques, and his experiences as a youngster getting the kind of personal and professional access to top rock acts that it’s hard to imagine someone starting out getting today. (I was among the authors who gave blurbs about this book on its back cover.)

23. Teenage Wasteland: The Who at Winterland, 1968 and 1976, by Edoardo Genzolini (Schiffer). Like Genzolini’s other books (on Cream in San Francisco in 1968 and concert memories of the Who), this mixes text with plenty of photos. Here the focus is on the Who’s concerts at San Francisco’s famous Winterland venue, almost ten years apart. These didn’t represent the Who’s only concerts in the Bay Area; even only counting the Keith Moon era, there were numerous others in the late 1960s and early 1970s, including shows at the Fillmore and Cow Palace. As in the author’s other books, the photos range from top-of-the-line professional to blurry and amateurish, in both black and white and color. This shouldn’t be such a big deal to intense Who fans, for whom the main thing is probably the documentarian aspect, especially as many pictures don’t appear elsewhere. A few photos of fans and other musicians are mixed in, including Leslie West, whose pre-Mountain group the Vagrants opened for the Who in 1968, and (faintly) Paul Kantner and Spencer Dryden of Jefferson Airplane, who were onstage watching the Who in 1968 at a Los Angeles show.

The best parts of the text include some eyewitness accounts of the shows by fans, though these could have been edited a bit down to the essentials. There’s also a technically-oriented interview from 1976 with Buck Munger, national promotion director for Sunn amplifiers when the Who were using and endorsing them in 1968. The author’s writing pads out the volume with general history of the group and Pete Townshend’s relationship to Meher Baba during this decade or so, and is prone to over-long paragraphs. One of the best features isn’t directly related to the Who: a reprint of the detailed syllabus for Fillmore Seminars, given in summer 1969 by top San Francisco rock business guys (including Bill Graham, producer David Rubinson, and radio legend Tom Donahue) for young people interested in entering the field.

24. The Rolling Stones: The Brian Jones Years!, by Peter Checksfield (peterchecksfield.com). Among Checksfield’s numerous books, this might not be as immediately valuable as some others—like his similar volumes on the Searchers, the Dave Clark Five, and even the Tremeloes—simply because the Rolling Stones’ 1960s work has been much more heavily documented than much of which he’s featured. Still, many—indeed most—Stones overviews don’t give detailed description of the many non-famous tracks the group recorded while Jones was in the Stones between mid-1962 and mid-1969. This details every one—not merely with the kind of meticulous release and recording dates in some other reference books (though this has the essentials), but with an actual description of the songs and the tracks. That might seem like something that should be obvious to offer in a Stones reference book, but there are few that cover, for instance, most of the songs (most of which are very good) on their 1967 album Between the Buttons, or B-sides like “Sad Day,” in detail. There are also informed descriptions of their known unreleased tracks, from 1962-63 demos through late 1960s outtakes, including notes about ones known or rumored to exist that haven’t yet circulated.

Checksfield is a generous reviewer—only committed fans, after all, are going to self-publish specialized books like this—but does sometimes criticize what he sees as shortcomings. There are also details of the recordings that are seldom discussed, like Brian Jones’s early backing vocals, or Charlie Watts’s prominent drumming on “Complicated.” Checksfield is more of a fan of the mid-’60s material that went beyond a blues-rock base and made room for Jones’s contributions on numerous unexpected instruments, but that’s okay, since that was a very fertile time, and he doesn’t ignore their blues beginnings and return to bluesier roots in the late ‘60s. It’s pointed out that, contrary to the impression some biographies give, he did indeed participate, sometimes strongly, in about half the tracks on Beggars Banquet, though his position in the band was becoming more fragile. Note that few tracks from the Let It Bleed album and era are included, as Jones didn’t play on most of those.

25. Cliff Richard: The Shadows Years: Every Song from Every Session 1958-1968, by Peter Checksfield (peterchecksfield.com). This follows the same format as the other Checksfield books on this list: succinct but descriptive reviews of all of Richard’s releases (on most of which he was backed by the Shadows) during the first decade of his career, with lots of black-and-white reproductions of picture sleeves from throughout the world, sheet music, and posters. While this might seem like an idiosyncratic subject to US readers, it should be remembered that Richard was almost as big as Elvis Presley in the UK. And while his music wasn’t as great as Elvis at his best, or too consistent, he made some pretty good records, especially in the earliest of these years.

Checksfield is of the mindset that Richard made many great records, and while I don’t share that enthusiasm, it doesn’t get in the way of plenty of details about the discs, some of which he does criticize for shortcomings. There’s also some coverage of alternate versions (of which there are surprisingly many), foreign-language recordings, tracks that came out years later on archival releases, and even bootlegs—of which, as it might again come as a surprise to US readers, there are a fair number. There’s also a section listing his TV and film appearances. Of particular interest to US residents like me is that, though he had just a couple of Top 40 singles in the American charts (and then not that high in the Top 40) in the late 1950s and early 1960s, he did appear on the Ed Sullivan Show three times in 1962-63, before the Beatles were known in the US; he also appeared on American Bandstand in 1962, and on a Pat Boone-hosted program in 1960.

26. My Mama, Cass, by Owen Elliot-Kugell (Hachette). The author is the daughter (and only child) of Cass Elliot, and as Elliot died when Elliot-Kugell was just seven, it might seem like there would be a slim body of memories to build a book around. This is still a pretty decent read, and in the first half or so, the author does relate a fair history of Elliot’s career and the Mamas & the Papas, though other books (especially Scott G. Shea’s recent All the Leaves Are Brown: How the Mamas & the Papas Came Together and Broke Apart) cover this territory in more depth. She did get a few stories—over the years, not necessarily for this book—from other Mamas & Papas and some others who knew Elliot, including Cass’s sister Leah.

More material of particular value not found elsewhere is the half of the book of how Owen coped with her mother’s loss and how her famous mom’s legacy affected her as she grew up. She had a sometimes troubled adolescence and early adulthood, often in Los Angeles and sometimes elsewhere, getting raised by Leah and (until they separated) her husband, renowned drummer Russ Kunkel. Elliot-Kugell’s attempts to establish a singing career of her own didn’t get far, in part due to some record business politics that curtailed her best shot at making an album. She also sang with Brian Wilson’s daughters and Chynna Phillips, but that group cut down to a trio without her before they had their own hit records. While sometimes overly sentimental in recounting how she eventually paid tribute to her mother by arranging for a star in Cass’s honor on Hollywood Boulevard, the ups and downs of negotiating the Hollywood entertainment and social scene as daughter of a famous entertainer hold some interest.

The following books came out in 2023, but I didn’t read them until 2024.

1. My Greenwich Village: Dave, Bob and Me, by Terri Thal (McNidder & Grace). Terri Thal was married to Dave Van Ronk, whom she managed for much of the 1960s, and she also briefly managed Bob Dylan near the beginning of his career. Her memoir focuses on her experiences during (and a little after) the folk revival, spanning the late 1950s to the early 1960s. Not so much a linear account as anecdote-focused memories organized into thematic chapters, this is an interesting read with plenty of wit and candor. It doesn’t shy away from some of the more disturbing aspects of the era, including some sexism within the scene (not from Van Ronk, it’s emphasized), unreasonable record company business practices, and increasing drug use that led to some deterioration of the scene by the late ‘60s. But it also takes a lot of joy in the music and community special to that time and place, as well as how the left-wing politics in which she and Dave participated affected what was happening.

While not every Van Ronk record is detailed, some are, and it’s especially interesting to read her frank reflections of how a 1964 LP he did for Mercury suffered because he and she (who took over supervising the recording) drank too much and didn’t let enough time pass before judging the results. The tapes sounded good to them the next day, but “later, when we heard the record, we were horrified; the music was sloppy. We never should have allowed it to be released.” This was the album with Van Ronk’s version of “House of the Rising Sun,” and the fairly famed incident in which Dylan took Dave’s arrangement for a track on his debut album before Van Ronk would record it—without Dave’s permission—is also detailed. So is Van Ronk’s venture into full-band rock with the Hudson Dusters, which Thal wasn’t enthused about, though she dutifully did as best she could managing a band instead of a solo performer.

Although “Bob” Dylan is part of the title, her professional relationship with Dylan, and her and Dave Van Ronk’s friendship with him and Dylan’s early girlfriend Suze Rotolo, is only central to one chapter, if occasionally referred to elsewhere. It’s still an interesting and important part of Thal’s story, and while Albert Grossman took over Dylan’s management early in the singer’s career, she and Dave remained good friends with him for a while. So there are stories of how difficult it was to book Bob at a time he was unknown and unknown solo folk singers in general had a hard time getting paying gigs. So are the stories of Dylan and Rotolo hanging out at her and Van Ronk’s apartment, and while not everything she remembers about Bob is flattering, generally her perspective is pretty positive. It’s poignant how, about five years Dylan’s stardom really took off in the mid-‘60s, he paid her a visit and “said he didn’t need money, but didn’t know what he could do other than perform.”

2. Oh, Didn’t They Ramble: Rounder Records and the Transformation of American Roots Music, by David Menconi (University of North Carolina Press, 2023). Rounder Records is one of the most noted independent labels of the last half century, specializing in all kinds of roots music, and occasionally even landing mainstream hits with George Thorogood and (much more heavily) Alison Krauss. While there’s a bit of a sweeping overview feel to some of this relatively compact volume (with about 180 pages of text), it’s an interesting story of how a company with modest resources succeeded, despite/because of sticking to the uncommercial music they cared about the most. There’s a lot of material drawn from extensive interviews with the three founders, along with others who worked with the company and several of its artists. Anyone interested in the independent side of the record business will find valuable accounts, particularly in how they scrapped together records and sales in their early days in the 1970s with little money, and with artists in entire genres (particularly but not limited to bluegrass) that had no hopes of doing much more than breaking even.

Perhaps understandably, the big successes with Krauss kind of overshadow coverage of the most recent few decades. There was room for a more substantial volume that might get into the stints of some of the more interesting artists who expanded Rounder’s original bluegrass/folk base, like Jonathan Richman, who’s merely mentioned. For that matter, there could have been more about their extensive licensing of vintage reggae material for the Heartbeat label, which seems likely to have had its share of colorful quirks. If you’re looking for quirks, there was a stipulation that when Iris DeMent’s contract was sold to Warner Brothers, Rounder got to reissue ten out-of-print records from the Warners catalog, which is how albums by John Hartford, Guy Clark, and the Charles River Valley Boys got on the label. If you’re looking for controversy, there’s not much, but it’s notable that although the founders had left-wing principles, they opposed the formation of an employee union in the late 1970s, hiring a Boston law firm that represented Richard Nixon during the Watergate scandal.

3. Sonic Life: A Memoir, by Thurston Moore (Doubleday, 2023). I’m more interested in the underground rock milieu (particularly in New York) from which Sonic Youth sprang than their music, but I still found much of this account from their (usually) guitarist and co-founder of interest. I don’t have as mixed feelings about many rock autobios as this one, and not only because I’m not a fan of the band. There’s a lot of inside detail about his and the group’s roots in New York’s no wave scene of the late 1970s and early 1980s, as well as his immersion in underground noise rock and punk, which took him from Connecticut suburbia to the heart of Manhattan’s alternative downtown arts scene. Much of it’s relayed in an inviting personal manner with a fair amount of wit and thoughtful perspective on his and his peers’ strengths and flaws, without the overt condescension or snobbery that afflicts some memoirs by figures who operated far outside of the mainstream. Initially, at least; Sonic Youth didn’t become as big as some of the acts they influenced or toured with, particularly Nirvana. But they did sign to a major label for a long time, eventually sold their share of records and played on bills with stars and iconic figures like Neil Young and Yoko Ono, and got to play on network TV and major festivals.

Moore traces this unlikely ascendance, but the coverage gets less and less intense and thorough from the late l980s onward, almost as though the text is putting a foot on the accelerator and rushing through the years with greater haste in the later sections. There are also many testimonies to how great and groundbreaking acts he admired were, particularly in concert, which can get wearing if you’re not a big listener to some of those. Although he occasionally mentions some obscure records and acts he admires as a huge collector of music (and books and zines) that aren’t in the noise-punk vein, most of the ones he depicts are. There’s a pronounced tilt toward music and approaches that were transgressive—sometimes obnoxiously so, as he sometimes acknowledges. That could please devotees of Sonic Youth and others working similar territory, and Sonic Youth’s own records and internal dynamics are often analyzed at length. There’s no doubting his enthusiasm for the alternative rock genres he and others were crucial to instigating, but it can feel like a limited world after many tributes to the value of noise and hardcore acts, from the most famous to the virtually unknown.

4. Euphoric Recall, by Peter Jesperson (Minnesota Historical Society Press). Jesperson was an important figure in the Minneapolis alternative rock scene in the late twentieth century, particularly through his involvement with Twin/Tone Records and a stint managing the Replacements. His autobiography includes plenty of material on those jobs, but traces his journey through the music business from his time as a teenage clerk in the city’s most famous record store, Oak Folkjokeopus, to his move to Los Angeles, where he worked at the New West label in the early twenty-first century. Along the way he was tour manager for R.E.M., if rather briefly, in their very early career. The meticulous detail of his recollections might be too much for non-indie rock geeks, as he often notes almost every stop on some of the Replacements/Residents tours. So might his unabashed enthusiasm for many, many bands he interacted with or just admired—not just pretty well known ones like the Replacements and R.E.M., but acts that might not be automatically familiar even to those who try to keep track of everything going on, like 13 Engines, the Dashboard Saviors, and early Minneapolis new wave acts like Fingerprints. Then again, it could be argued that all-out music enthusiasts like Jesperson are precisely this book’s audience, and want to know as much as they can about Paul Westerberg’s songwriting and cult acts like Jack Logan, whose career Jesperson was vital to enabling.

Although his tone is usually upbeat, almost excitedly so, the harder knocks of the music business aren’t ignored. He might have just been too much of a fan, and too nice a guy devoted to music more than the bottom line, to rise to the top echelons of the business, though he did pretty well. He was let go from R.E.M. as tour manager, he notes (if briefly), in part because the group wanted someone more hard-nosed. The Replacements fired him as manager after a few years in the kind of not-fully-explained fashion that’s pretty common in rock. That band’s legendary erratic shows and rowdy and sometimes downright repellent behavior, such as thoroughly trashing a touring van Jesperson had gone to pains to secure, is also not ignored, though perhaps not criticized as much as it could have been. Jesperson himself developed an alcohol problem so serious it threatened his life, though he’s now been sober for decades. While his extensive time at New West isn’t covered as much as his Minneapolis days, here too he raves about acts that didn’t catch on in a big way, like the Leatherwoods, and notes that he his focus on helping acts whose music he loved ultimately made it hard to survive in an increasingly profit-minded record business.

5. Crying in the Rain: The Perfect Harmony and Imperfect Lives of the Everly Brothers, by Mark Ribowsky (Backbeat). For all their monumental importance to rock history, the Everly Brothers haven’t been honored with many biographies. This is only the second one I’m aware of, and at this point it’s hard to do many first-hand interviews for such a project, with both Everlys gone, as well as most of the important people with whom they were associated. There doesn’t seem to have been much if any such research for this effort, although it ties together much of which is known, itself a service given the lack of books about the duo. This doesn’t just highlight the hits, discussing many of their albums, even some of their obscure ones, in depth and providing a lot of detail about both the hits and their many fine lesser-known tracks. Their sometimes troubled fraternal relationships and marriages are also covered, though friction between Don and Phil might be played up to some degree. There’s a little too much contextual detail about the popular music scenes in which they operated, and the text often throws lists of tracks and chart positions at the reader, though there’s much considered critical analysis as well.

Although it’s not too easy to find now, Roger White’s slimmer 1984 book The Everly Brothers: Walk Right Back is recommended as a supplement to this new one. It doesn’t have as much description of the tracks and specific albums and singles, but does have a good deal of first-hand interview material, along with a wealth of photos. Both volumes also document their touring activities, and Crying in the Rain has a lot of material on numerous TV appearances.

Thank you for your generous assessment of my recent books, appreciated as always. To add to what you’ve written here, I was forced to withdraw my DC5 book by a certain ex-member, whom I made the mistake of sending a copy to (I’ve since also removed the text-without-images from my website, as he can afford better lawyers than I!). All very different from my books on The Searchers and The Tremeloes, where pretty much every surviving key members were of help. Still, I’m glad I wrote it! A band that will remain very overlooked thanks to one man’s (in)actions.

Of the other publications listed here, the only one I’ve read is The Liverbirds book, which I enjoyed alot. I’m a big fan of The Everly Brothers, but none of the reviews of the book here have enticed me to read it (as with my own books, I’m far more interested in the MUSIC than the scandals & squabbles).

All the best for 2025.