What makes an album surprising? The criteria will differ widely according to who’s making the judgment. Weren’t all of the Beatles albums surprises, in how each marked not just a significant departure and progression from the previous one, but often wholly unpredictable ones as well? Aren’t albums surprising in which a performer noted for a very specific style moves into a very different one, as Bob Dylan did on his electric rock recordings in the mid-1960s? How about ones that many consider to be duds, Dylan providing another example with 1970’s Self-Portrait?

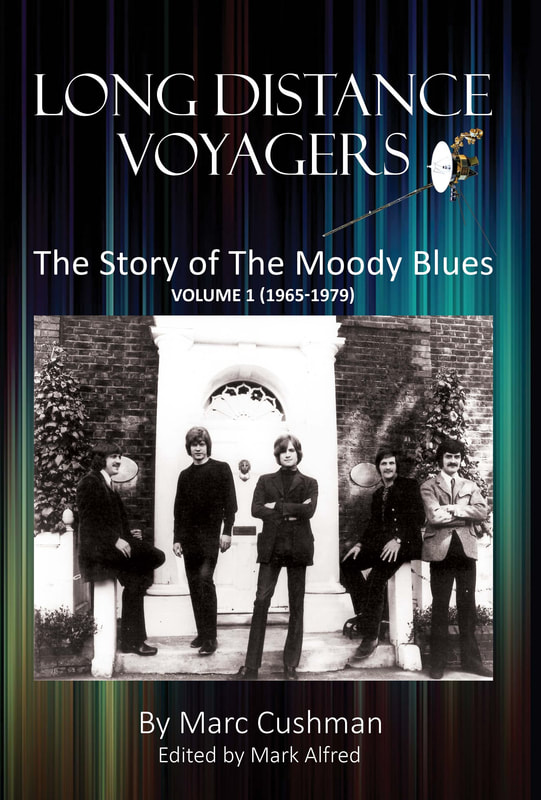

Although none of the records noted in the above paragraph make the list on this post, most people can probably agree that surprising records are ones that don’t match, and sometimes even defy, expectations given an artist’s past releases. I thought about this recently after reading a new 800-page (yes, 800 pages – and it only goes through 1979!) book about the Moody Blues, Long Distance Voyagers. The Moody Blues aren’t for everyone, and an 800-page book about them definitely isn’t for everyone, or even every Moody Blues fan. But it naturally has a lot of coverage of their most famous album, Days of Future Passed, which was a pretty radical departure from their early sound when it came out in late 1967.

Were many other significant LPs of the late ‘60s so different than what had preceded them? Not many – an inarguable point even if you don’t like the Moodies. There were some others that came close, in pretty different ways. The common thread on my personal Top Ten list here is the genuine sense of WTF reaction that must have greeted these records when they were first spun, even by dedicated fans. Some were baffled, some exhilarated, some outraged – but no doubt almost all of them were surprised.

The late ‘60s, of course, were not the only era in which such albums were unleashed. Over the next ten or fifteen years, others would appear that were strong candidates for lists of the some surprising LPs by significant artists, again for very different reasons – unlikely comebacks (Marianne Faithfull’s Broken English), utter departures from their usual approach (Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska), wholly uncommercial excursions into the avant-garde (Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music takes the cake in that regard), or outings so stylistically uncharacteristic they seemed designed to piss off longtime fans and record companies (Neil Young’s Trans, as well as several others he’s done). Analysis of those holds some interest, but is best left to different writers. I’m sticking to the era which I know the best – the late 1960s, the one in which Days of Future Passed was released.

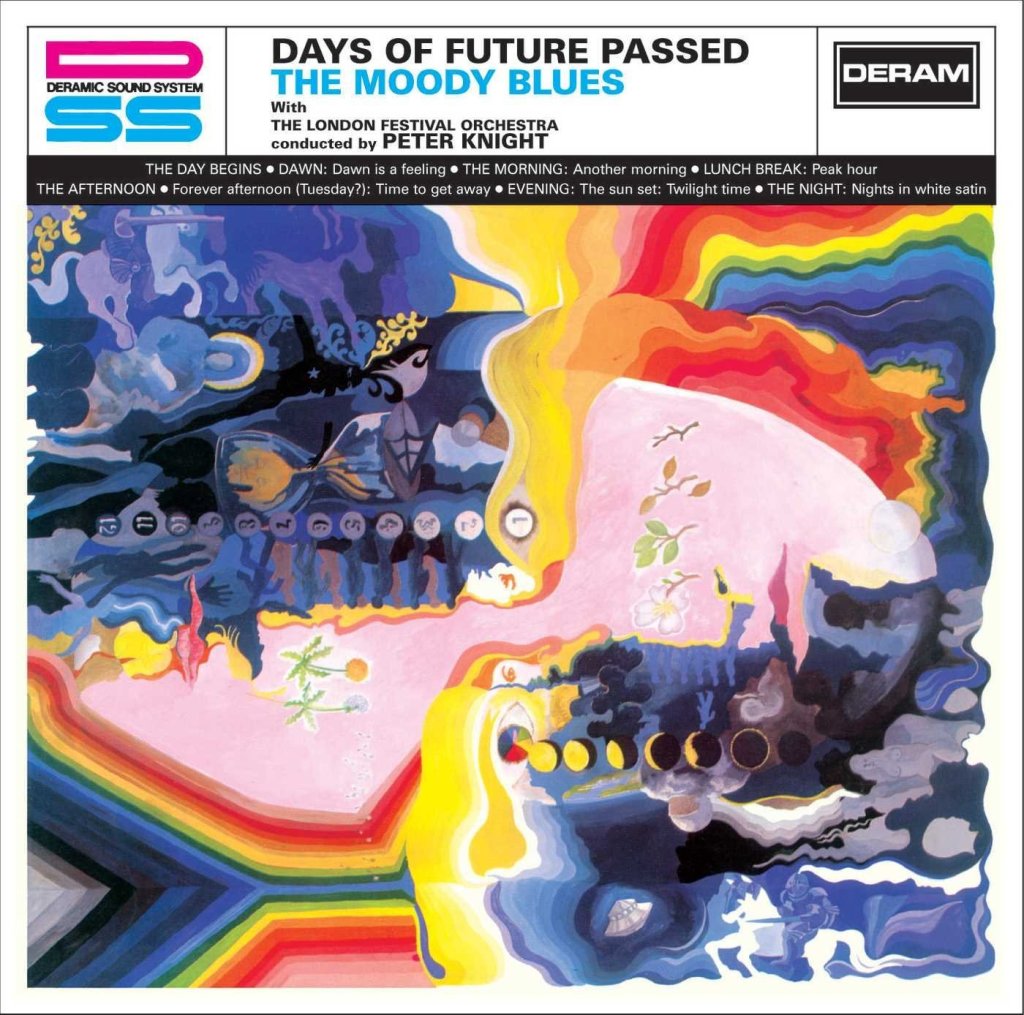

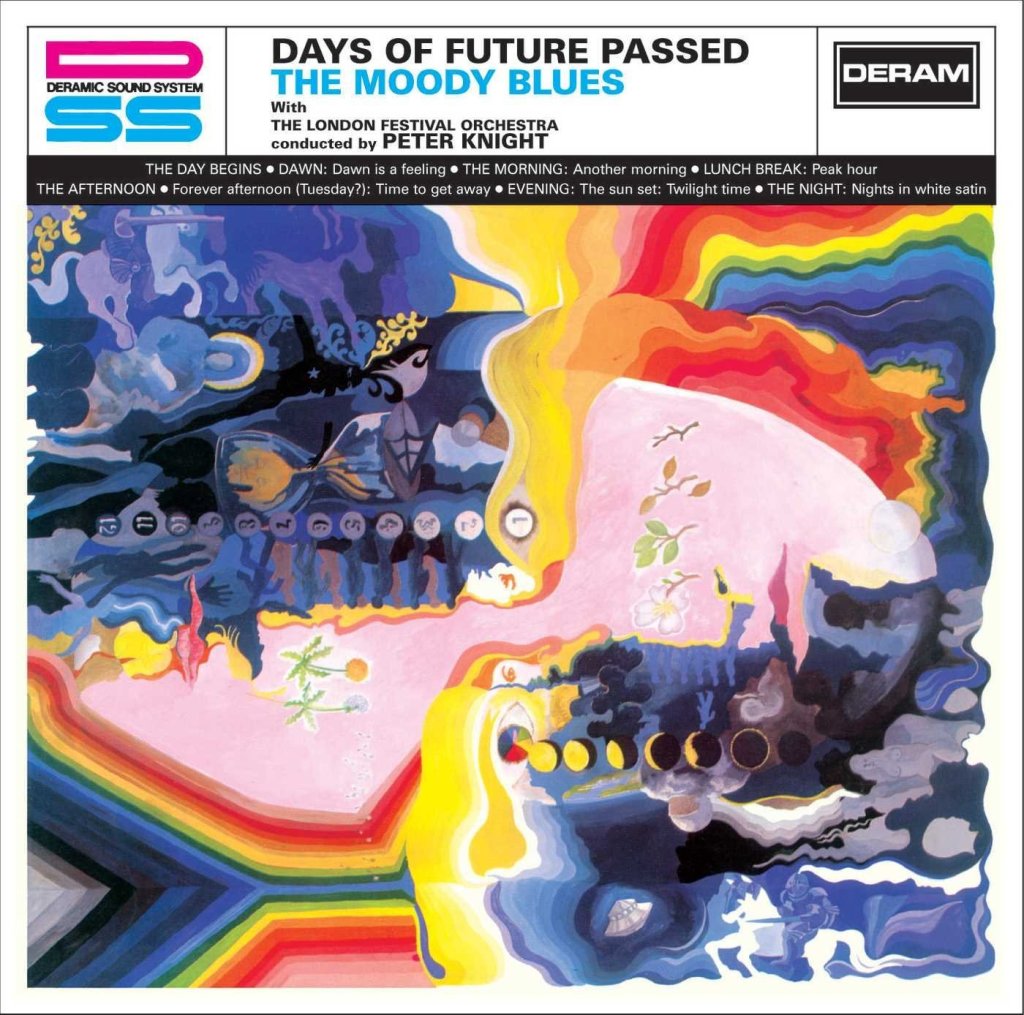

1. The Moody Blues, Days of Future Passed (1967). Albums two and three on this list are vastly more critically respected than this one, and certainly album number two got much more press for defying expectations than this LP did. But really, have there been any other significant records that were as unlike what listeners would have predicted?

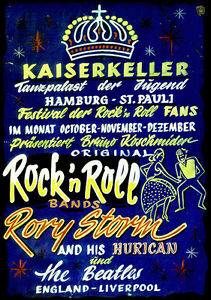

Admittedly, a big reason for their shift in direction was a substantial change in personnel. For about two years, starting with their debut single in late 1964, the Moody Blues were a good, though not great, British Invasion band with a haunting R&B/pop blend. The only song for which this lineup of the band (featuring Denny Laine, later of Wings, on lead vocals) is famous is their only big hit, “Go Now.” But they had quite a few other good tracks in the mid-’60s, many of them written by Laine and the group’s piano player, Mike Pinder. By fall 1966, Laine had enough of their fading commercial prospects and quit, their original bass player (the forgotten Clint Warwick) having already left.

For a year or so, the Moody Blues somehow struggled onward with replacements Justin Hayward and John Lodge, issuing a couple more flop singles. The story’s often been noted elsewhere (and is naturally told in considerable detail in the new Long Distance Voyagers book), but they were given the option of doing another LP whose function would be to demonstrate a new stereo recording method developed by the Deram label. The story has varied somewhat in different accounts, but the Moodies’ job would be to record a rock version of a symphony by Dvorak.

With no other real opportunity on the horizon, the band accepted — but then jettisoned the concept and substituted their own, that being a song cycle about different parts of a day from dawn to nighttime. It was a risk that in some ways might have been foolhardy (though not as foolish, perhaps, as just doing a Dvorak symphony as they were told), or at least resulted in them being kicked off the label and unable to find another recording contract. Probably more than 95% of the bands in a similar position wouldn’t have been able to pull it off. The Moody Blues did, reinventing themselves as an act bridging psychedelia and progressive rock with somber, stately songs with thoughtful-to-the-point-of-pompous lyrics, gothic vocal harmonies, and Pinder’s eerie Mellotron, marking him as the first adept user of the instrument in rock music. They sounded little like the Moody Blues of “Go Now” days with Denny Laine’s vocals, save for ingredients surviving in the haunting melodies and backup harmonies.

It was a career move that’s been hailed as not only adventurous, but courageous, the Moodies sticking out their necks for what they believed in when the record label funding the project was expecting something totally different. Which I agree with, but really, what did they have to lose? They’d made some good records in their early poppier style, but that approach wasn’t getting them anywhere in 1967. An album of Dvorak interpretation, aided by classical interludes, wasn’t going to make them commercial or critical favorites either. Indeed, it might have made them laughing stocks for being stooges for a company project aimed at hyping a stereo technique. Why not throw caution to the wind and go for broke, consequences be damned? They were probably going to break up anyway if they didn’t come up with a miracle — and that miracle wasn’t going to be the Dvorak album. The only chance they had, in the ultra-competitive world of 1967 rock, was coming up with their own distinctive original material.

It seems that at least a few people at Deram knew what the band was up to, but it would have been great to be a fly on the wall at the meeting at which the result was played to Deram staff expecting a somewhat exploitative Dvorak-meets-the-Moodies LP primarily designed not to advance the band’s career, but to show off their “Deramic Sound System.” Perhaps figuring it didn’t make sense to throw yet more money away to bury or redo the project, Deram released what the Moody Blues gave them. And everyone won, the album quickly gaining strong sales and positive feedback from fans and critics, and over time (which took a good few years) becoming a huge seller.

Something to emphasize that isn’t always pointed out when this tale is told: although the Moody Blues deserve praise for doing something both daring and true to their hearts with Days of Future Passed, it wouldn’t have worked if the songs weren’t strong. Indeed, they made for a stronger batch than any of their other albums, most made when they were established as a top act. Had the songs been on the okay-but-rather-unmemorable level of their pre-Days of Future Passed singles from 1967 with the Hayward-Lodge lineup, or the “Nights of White Satin” B-side “Cities,” the album would have been forgotten, even with the same concept and structure. And while Peter Knight’s instrumental classical interludes linking the band tracks can seem corny at times (the bit before “Peak Hour” almost sounds like the background to a frenetic city scene in an industrial training film), the album would not have worked as well without them, as they were vital to establishing a sense of epic grandeur.

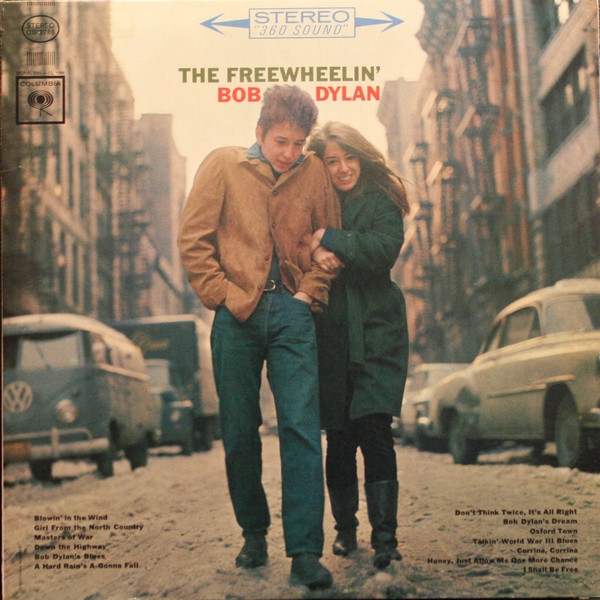

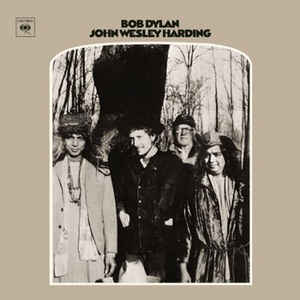

2. Bob Dylan, John Wesley Harding (1967). As albums by artists who were already influential stars went, none was as surprising as John Wesley Harding, released in the final days of 1967. As Mike Jahn wrote in his 1973 book Rock, “As expected, it thoroughly stood folk and folk rock on their heads.” But not the way fans expected. It had been a year and a half since Dylan’s last album, Blonde on Blonde, which doesn’t sound like much now, but was an eternity by 1966-67 release schedule standards. In that year and a half following a July 1966 motorcycle accident, Dylan hadn’t played any concerts or released any singles, or even appeared much in public, sparking rumors of death or crippling injury. In that same year and a half, rock had changed at a dizzying pace, often getting louder and more psychedelic.

Some listeners had to expect that Dylan’s next album might have been, if not psychedelic, even louder and more far-out than Blonde on Blonde, itself quite a bit louder and crazier than his early folk recordings. Instead John Wesley Harding was quiet, country-folkish, and barely electric, as though he was consciously restraining himself from rocking out. His lyrics were (with the exception of a song or two) as sophisticated and enigmatic as ever. But soundwise, he’s since been hailed as heading the rock world’s retreat from psychedelia to a back-to-basics, earthier approach, though in truth rock might have headed that way anyway as the possibilities of psychedelic music began to exhaust themselves, as they do in as any major innovative musical movement plays out.

John Wesley Harding’s almost quotidian calm was almost as contrary as possible to almost any Dylan fan’s expectations. Given Dylan’s already iconic stature in the rock world in 1968, many would pick it as #1 on a list of this sort. However, one factor in particular makes me reluctant to consider it for the top position. Although it wasn’t widely known at the time, Dylan was making a lot of music in 1967, if outside of conventional recording studios. Tons of music, in fact, as the recent six-CD expanded edition of The Basement Tapes verifies. By the late 1960s, some of it would be bootlegged, and of course many of the more accomplished songs found official release on the 1975 double-LP version of The Basement Tapes.

The Basement Tapes weren’t quite as hard-rocking as Dylan’s fiercest mid-’60s electric music, though they’re closer to Blonde on Blonde than John Wesley Harding. But they draw more on rootsy blues, country, and gospel than Blonde on Blonde, and if they’re not exactly halfway between Blonde on Blonde and John Wesley Harding, they’re something of a bridge. Had the best of The Basement Tapes been released in 1967, whether as a single or double LP (and re-recorded in a conventional studio to boost accessibility), they likely would have been very well received, and generated only mild surprise for not being as loud or outrageous as some might have expected. Now that so many Basement Tapes are available, the transition from Blonde on Blonde to John Wesley Harding seems less shocking, though hardly insubstantial.

As a footnote, at least a few people besides Dylan and the Band had heard some Basement Tapes before John Wesley Harding was released, when a few of them were circulated inside the industry with the intent of generating cover versions in late 1967. But almost everyone who heard John Wesley Harding shortly after its release had not heard any of these. Indeed, very few listeners even knew of their existence. So The Basement Tapes would not have mitigated the shock for any average purchaser of the John Wesley Harding album when it first appeared in stores.

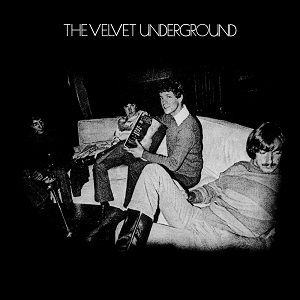

3. The Velvet Underground, The Velvet Underground (1969). Each of the Velvet Underground’s principal four studio albums (a couple outtakes compilations subsequently appeared in the 1980s) was markedly different from each other. Still, I’d have to say their self-titled third album was about as unlike what any of their growing cult fandom would have expected when it came out in March 1969. Having made one of the weirdest and noisiest records of all time with their previous album, White Light/White Heat (released in early 1968), the Velvets now seemed perversely determined to make the quietest album of all time, at least in places.

I got the record (as a UK import; it was out of print in the US) as an 18-year-old in 1980, and still remember the shock of putting the needle down on the opening track, “Candy Says,” in which the group seem to be deliberately playing in as subdued and restrained a manner as possible, as if they’re afraid nudging the volume up even a bit would cause the needle to skate across the vinyl. And this was after having been thoroughly prepared for the VU’s change in direction by reading retrospective reviews of the LP (which weren’t all that easy to find in 1980, actually).

The Velvet Underground does rock out harder on some tracks, like “Beginning to See the Light” and “What Goes On,” and even gets avant-garde near the end on “The Murder Mystery.” But almost everything, even the mid-tempo rockers, is suffused with a feeling of containment, to the point where guitarist Sterling Morrison famously said (as a compliment) that it sounds as though it was recorded in a closet. It’s as if they’re trying to consciously annoy the fans who wanted more “Sister Ray” and the like by supplying the complete opposite.

With hindsight, however, we can put down much of the change in the Velvet Underground (as with the Moody Blues on Days of Future Passed) to a major lineup shakeup. John Cale was fired by Lou Reed shortly before the sessions for the album, replaced by more conventional (but very accomplished) rocker/singer Doug Yule. Allowing in turn for more conventional, melodic, and romantic songs by Reed, the results were excellent, and actually substantially more commercial than White Light/White Heat.

At the time, however, it confounded and even disappointed a good number of the fans the Velvet Underground had picked up — which weren’t nearly as great in number back then as Bob Dylan fans, or even the number of fans the Moody Blues had after Days of Future Passed. “A lot of people didn’t like our third album because they wanted more of the second,” Reed acknowledged to Metropolitan Review in 1971, after explaining he thought of the Velvets’ first three LPs as different installments of a novel or opera of sorts. “But they didn’t understand that that’s as far as you go with that, then there had to be a release, there had to be an ending. But I needed room to work, so I needed a separate album for each phase. I couldn’t have the ending on the second album, the second album ended very harsh. Then the third album starts out soft. So that was the idea all along, but no one seemed to pick up on it.”

As surprising in the context of a career as John Wesley Harding, I nonetheless put The Velvet Underground one notch lower, mainly for the following reason. John Wesley Harding’s change in direction was a shock for literally millions of listeners. The Velvet Underground’s, if equally profound, was at the time likely noticed by tens of thousands at most. It can’t compare in the magnitude of shock waves it generated, though fifty years later—with the massive expansion of the VU’s audience—it probably does have millions of listeners.

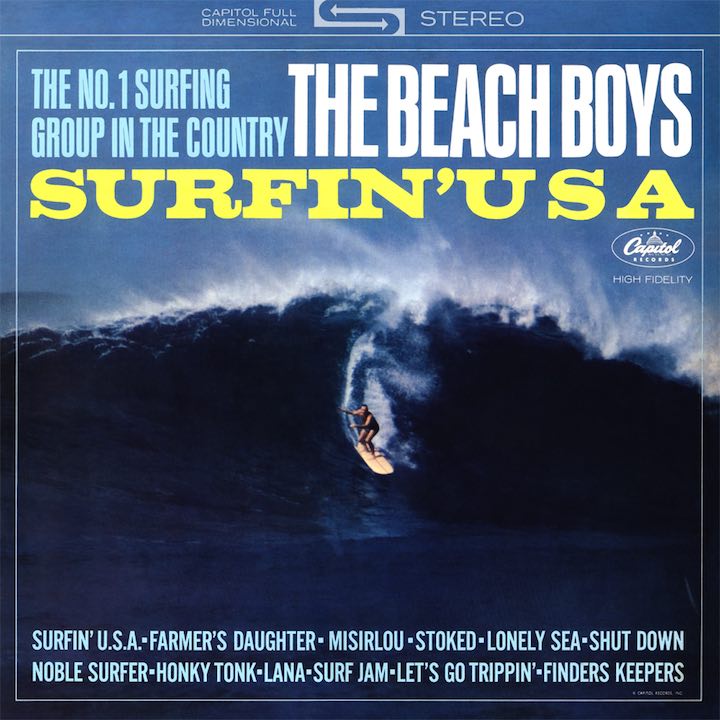

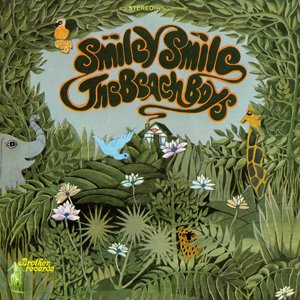

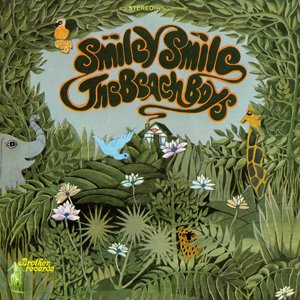

4. The Beach Boys, Smiley Smile (1967). Albums can be surprisingly disappointing, as well as genuinely surprising. This is the standard-bearer for such a record on this list. It’s almost a cliché to cite this 1967 LP as a massive letdown, or, as Beach Boys guitarist Carl Wilson famously described it, “a bunt instead of a grand slam.” But a letdown it was, after the sky-high anticipation fostered by reports of Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys working on an album that would out-innovate the Beatles.

That record, Smile, would never appear, and never even get properly finished, though simulations of what it would/could have sounded like (along with mounds of outtakes) have come out on both official CD and bootlegs. Although Smiley Smile was largely derived from subsequent and entirely different sessions, you couldn’t blame many consumers for expecting Smile when they bought it in 1967. The title was pretty similar, for one thing. And it had some songs (if not always in the same versions) that almost certainly would have been part of Smile, particularly the single “Heroes and Villains,” but also “Wonderful” and “Wind Chimes.”

Apart from not sounding as groundbreaking, or just sounding as good, as what listeners expected/wanted after reports of the Smile sessions, Smiley Smile often sounds downright peculiar. With the non-Brian Wilson Beach Boys now determined to play their own music after classic mid-’60s records on which their contributions were largely limited to vocals, the tracks sound rather anemic. There’s an abundance of self-conscious, rather silly (if inoffensively so) humor, as though they’re not taking the endeavor entirely seriously, now that they’ve abandoned shooting for the moon. A classic single with pull-out-the-stops production (“Good Vibrations”), like “Heroes and Villains,” sounds out of place next to much more casual, tossed-off arrangements (including inferior versions of the Smile sessions standouts “Wonderful” and “Wind Chimes”) that can sound a bit like informal run-throughs. Some listeners find that informality charming, but it also veers on sounding like outtakes rather than finished arrangements, or something fun to hear on bootlegs, but not on par with the band at full throttle.

There have been some efforts to rehabilitate Smiley Smile, championing it as a rebirth of the Beach Boys’ collective group spirit, or as a continuation of their evolution rather than the signpost to the end of the band’s peak. I take pride in puncturing or deconstructing critical party lines in rock history when the music and facts call for it, but at the expense of losing a few friends on my social media lists, I’m afraid I’m siding with the party line here. Smiley Smile is a big letdown, especially when stacked against not only the buildup when Smile was being recorded, but the actual brilliant (if often flawed) Smile outtakes that are now freely available.

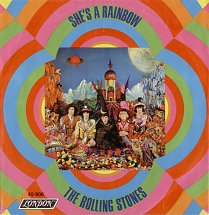

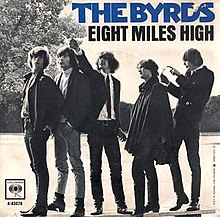

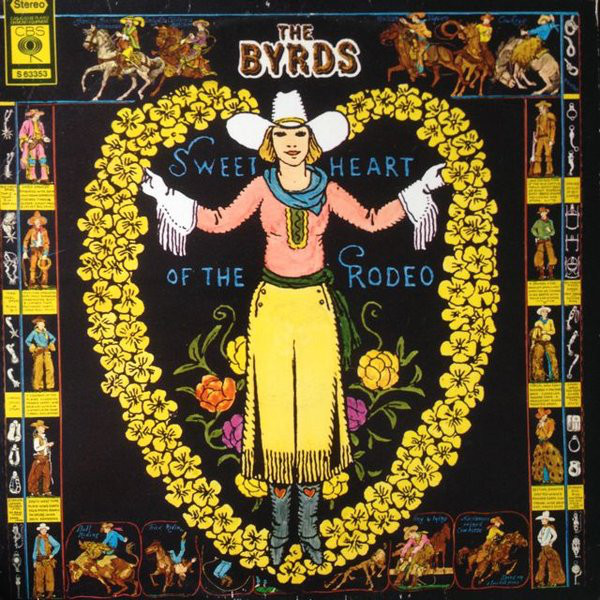

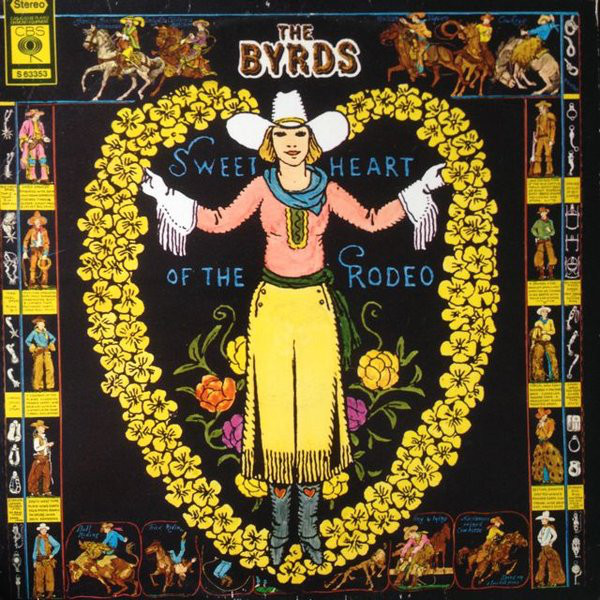

5. The Byrds, Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1968). Much like Bob Dylan’s move to country-influenced sounds with John Wesley Harding was a shock, so was the Byrds’ sixth album, Sweetheart of the Rodeo, when it came out about eight months later. The Byrds, along with Dylan, had been the leading lights of folk-rock; now they were fully on board with country rock. Dylan’s transition to country rock cost him virtually nothing commercially; John Wesley Harding was a big hit, if maybe not quite as big as it might have been if he’d done Blonde on Blonde Part 2. Sweetheart of the Rodeo, as many five-star reviews as it would get in rock history magazines and online sites decades later, was not a hit, in part because it wasn’t anything like what people expected from the Byrds.

Of course, much of that was down to personnel changes that had rocked the core of the band. Just two of the original five Byrds were left. Still, one of them was leader Roger McGuinn, and the other, bassist Chris Hillman, had become an important singer-songwriter contributor to their pair of 1967 LPs. Yet the characteristic electric jangle of their first five LPs was gone, pretty much. And country rock that often sounded close to straight country music was in its place, at a time when country music wasn’t very popular among much of the rock audience. Even the two Bob Dylan covers (of Basement Tapes songs Dylan had yet to release, no less) didn’t have the jangly, vocal harmony-laden appeal of “My Back Pages,” “Chimes of Freedom,” and several other Dylan compositions the Byrds did masterful versions of on their 1965-67 releases.

While many Byrds fans knew the group now had a couple non-founder members, few were aware of just how profoundly one of them, Gram Parsons, had changed the band’s overall direction. With the enthusiastic support of Hillman, the group abandoned McGuinn’s ambitious plan for a double album spanning the history of music, from traditional Appalachian folk to experiments with the then-new synthesizer. Nor were the band writing as much original material as usual.

The record’s since been hailed as a country-rock milestone by many. I confess I’m not one of the critics who admires the album. I think it’s pretty disappointing and rather dull — a statement that’s another ticket to losing Facebook friends. I champion change and unpredictability among top rock innovators, but had I been old enough to buy it in 1968, I admit my gut reaction would have been to mourn the death of the “classic” Byrds sound. As I’ve written elsewhere, I also wish the Byrds had tried McGuinn’s idea to span the history of music, as prone as that might have been to failure.

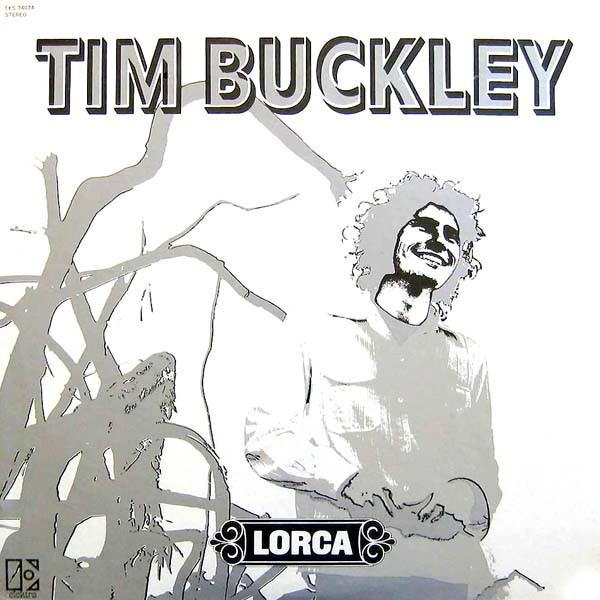

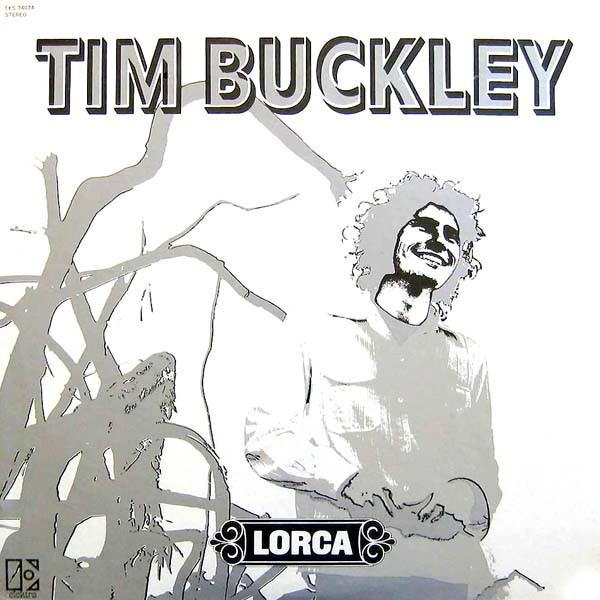

6. Tim Buckley, Lorca (1970). Released in 1970 but recorded in September 1969, Lorca was one of the most defiantly inaccessible albums by any rock artist, not counting pure avant-garde outings like Metal Machine Music and the early collaborations by John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Buckley had not been the most accessible of singer-songwriters on his early albums, progressing from slightly arty baroque folk-rock to orchestrated art song to near-jazz. But those LPs had been full of actual songs, and for the most part pretty pleasant ones, if often challenging in their lyrics and structure.

Side one of Lorca was not occupied by conventional songs. The dissonant tones and pipe organ of the opening track were more reminiscent of contemporary composers such as Olivier Messiaen or Arnold Schoenberg than of rock, folk, or even jazz. Buckley proceeded to moan with a shaking vibrato, often wordless, sometimes rumbling and sometimes gliding into pealing shrieks, that conveyed not so much anguish as it did sheer agony. It was art, but to unschooled rock listeners, it sounded like the atonal soundtrack to an acid-fueled monster movie.

The free-jazzish track occupying the remainder of side one, “Anonymous Proposition,” was only slightly more approachable, impressive as it was in Buckley’s almost athletic journey across several octaves and vocal shadings. Never mind that the second side of Lorca had material far more in the jazz-folk-blues mode of his 1968 LP Happy Sad, albeit looser and funkier. Some listeners might not have even gotten that far.

The label that released Lorca and Buckley’s first three albums, Elektra, was regarded as about the most artist-friendly record company of the time. But even Elektra had its limits, dropping Tim after Lorca. As Elektra chief Jac Holzman told Musician about the Lorca era years later, “He was really making music for himself at that point. Which is fine, except to find enough people to listen to it.”

Like David Bowie and (in jazz) Miles Davis, Buckley changed styles with unnerving frequency and unpredictability. Unlike Bowie and Davis, he hadn’t built up the sizable audience whose base was large enough to ensure that much of it would follow his career, even as some of it dropped out along the way (and others joined partway into the journey). Lorca’s very small audience didn’t dissuade him from continuing his idiosyncratic path, with parts of Starsailor (also released in 1970) just as strange, followed by unsuspected leaps into more commercial funk-singer-songwriting. As admirable as its uncompromising first side was, it ensured that Buckley remained a cult figure.

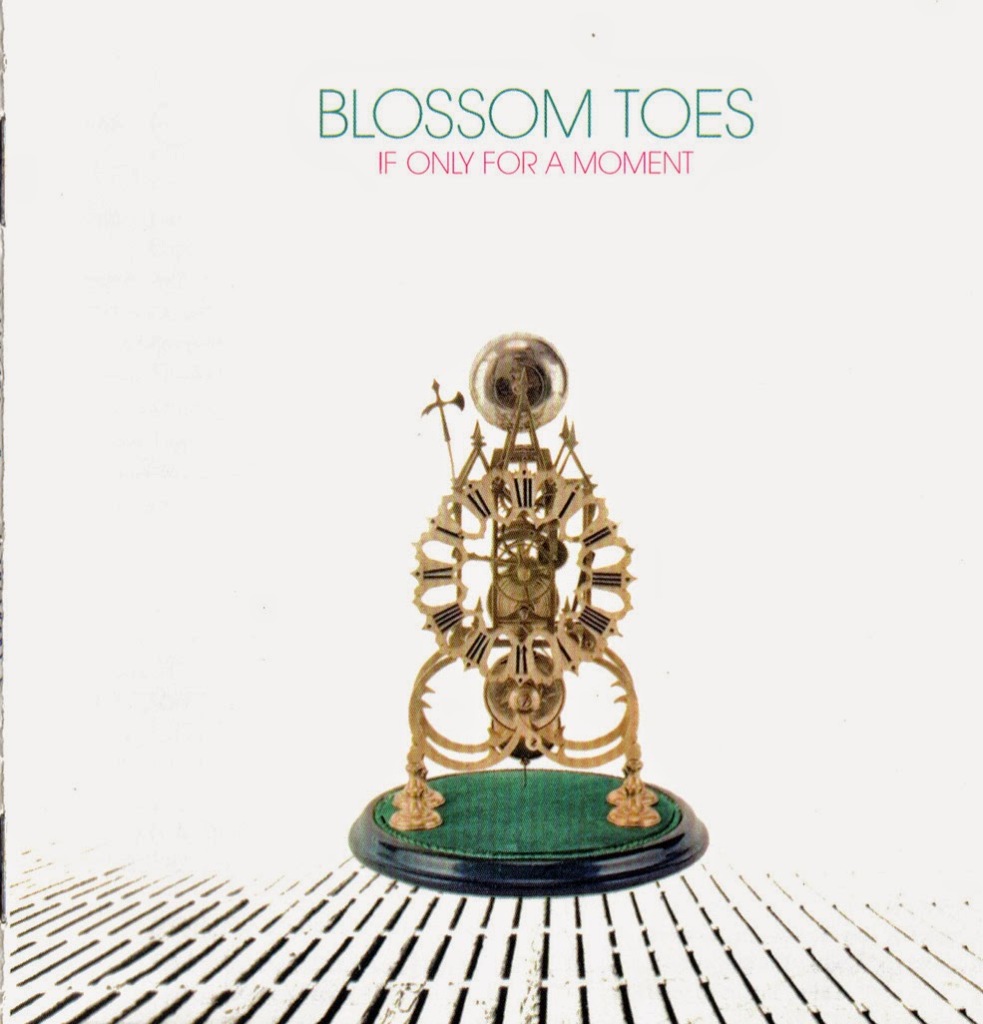

7. Blossom Toes, If Only For a Moment (1969). All of the other acts on this list are pretty well known, even if some of them are on the cultish side. Not so Blossom Toes, who make Buckley seem like Bowie. The British band put out just two albums, though these LPs mark them as one of the best and most interesting obscure groups of the psychedelic era. And of all the bands in rock history that have recorded just two albums, few can match the Blossom Toes’ rare feat of producing LPs that were not only first-rate, but totally different from each other.

Blossom Toes’ debut, 1967s We Are Ever So Clean, was charming whimsical British pop-psychedelia, somewhat like the Kinks jamming with the Salvation Army on the village green on Sunday afternoon. In contrast to the debut’s orchestrated pop-psychedelic summer-day whimsy, If Only For a Moment was all heavy guitars and March of Doom lyrics, closer in tone to Captain Beefheart than the Kinks. It’s far more accessible than Trout Mask Replica, however, with some of the classiest proto-progressive rock dual guitar leads (between Brian Godding and Jim Cregan) you’re likely to come across.

The group’s wistful vocal harmonies are also intact—the only real strong link between the two records. But the chirpy chamber orchestra of the first LP is gone for good. The somber lyrical tone of the extended compositions deals with bombs, war protests, and tortured uncertainty. It’s almost as if the smiley face of the debut album has been inverted into a puzzled frown.

At this point Blossom Toes might be more widely known to the international record collecting community than they were back in the ‘60s. Indeed, the number of albums issued by Blossom Toes during their lifetime is now exceeded by the number of discs of unreleased material available by the same band. They remain, however, virtually unknown to the general public. They’ll never have the cult of Tim Buckley or the Velvet Underground, but they deserve a wider hearing, even if your initial impression will vary enormously depending on which of their two albums you’ll hear first.

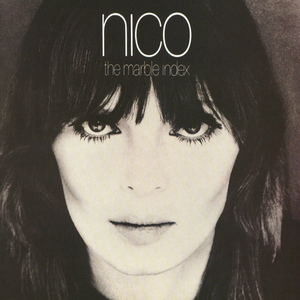

8. Nico, The Marble Index (1968). Nico is not tremendously obscure, due mostly to her association (actually fairly brief) with the Velvet Underground. Her second album, however, was truly obscure upon its release. It did generate a surprising number of thoughtful, and at times even positive, reviews. Judging by how hard it was to find used copies back when I was buying Velvet Underground records around 1980, however, it must have sold very little when it first came out.

For those who were paying attention, it must have been a tremendous shock after hearing the three Lou Reed songs Nico sang on the first Velvet Underground album, and then the baroque folk (often orchestrated) on her almost as obscure debut solo LP, 1967’s Chelsea Girl. For one thing, Nico wrote virtually nothing on Chelsea Girl (though she got a partial writing credit for the sole track to sound like the Velvet Underground, “It Was a Pleasure Then”). On The Marble Index, she wrote everything. Not only that, it sounded nothing like the rather gentle pop-folk of Chelsea Girl. Instead it presented harsh, uncompromisingly bleak soundscapes dominated by her stentorian, icy vocals and somber harmonium.

As is now fairly well known, Nico was encouraged to start writing her own songs by Jim Morrison, with whom she’d had an affair, Morrison advising her to take inspiration from her dreams. Likely dismissed as a token glamour girl in the Velvets by many of their observers, she was eager to become more of an artist than a pretty face. Remarkably, she succeeded, and with an original style not easily comparable to either the Velvet Underground, the folky songs she’d done on Chelsea Girl (which seemed to be trying to make her into an underground Judy Collins of sorts), or the singer-songwriters (like Tim Hardin and Jackson Browne) she’d covered on the Chelsea Girl LP. She did have a great deal of help in this regard from fellow Velvet Undergrounder John Cale, without whose arrangements The Marble Index might have sounded too monotonous and meandering.

As it turned out, the music she did on The Marble Index would be far more typical of her solo career than what she’d done on Chelsea Girl or with the Velvets, Cale returning to help with the production and arrangements on much of her subsequent studio work. The Marble Index, like Nico herself, did gain more of a following over the next few decades, and is now available as part of an extensive double CD (with her 1970 album Desertshore) that includes almost a dozen outtakes. It is as unlike Chelsea Girl, however, as the second Blossom Toes album was from that group’s debut—a major difference between the acts being that Blossom Toes would then break up, while Nico would put out four more studio LPs, the last appearing in the mid-1980s.

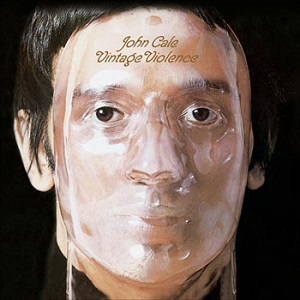

9. John Cale, Vintage Violence (1970). Recorded in fall 1969 and released in 1970, John Cale’s debut album was wholly unlike what many expected—but not because, as was the case with several other albums cited here, it was weird. On the contrary, it was a shock because it was so damned normal. Or, at least, way more normal than you’d expect given Cale’s reputation as by far the most avant-garde member of the Velvet Underground, and by his many way-avant-garde (indeed, sometimes pretty unlistenable) prior recordings in the 1960s, though very few of them had been heard before they surfaced on archival CDs decades later.

Vintage Violence was a shock not for the radical nature of its sounds, but for the absence of virtually any radicalism at all. Instead, it was a relatively conventional singer-songwriter record. It was more normal, in fact, than anything the Velvet Underground had recorded, or for that matter any of the records Cale had made with Nico, the Stooges, or Terry Riley. It’s certainly more accessible and less jarring than any of those albums. (Cale’s collaboration with Riley, Church of Anthrax, did not come out until 1971, but the pair had started working on material together in the studio in March 1969, about six months before the Vintage Violence sessions.)

Instead of taking cues from his experimental past, Cale instead plugged into the earthy roots-rock of the Band, who by late 1969 were among the most influential groups in the music business. There were also elements of country-rock, folk-rock, and the introspective singer-songwriting now gaining currency in the pop LP market. Cale sings in a gentle and attractive, if somewhat restrained, voice, backed by the band Grinder’s Switch.

Listeners paying attention to the Velvets and Cale’s prior work certainly would have been far more steeled for something like Church of Anthrax. Just because Vintage Violence is conventional, however, doesn’t mean it’s bad. Far from it, actually. It’s a fine, accessible, pleasing record, full of intelligent if low-key songs, the only avant-garde weirdness popping up (and pretty mildly) on the macabre “Ghost Story.” It’s impressive too for the courage it took for Cale to attempt something not at all like the Velvet Underground, and his ability to pull something of the sort off.

For all its quality, Cale has been pretty modest, and sometimes even dismissive, in his assessments of Vintage Violence. They’re worth quoting at some length here:

In the liner notes to the 2001 CD reissue of the album, he calls it “a very naive record. Those songs were written immediately prior to recording them. I tried to imitate my favorite songwriters of the times, the Bee Gees or whatever. I was out to discover the world of pop songwriting and I thought tunes were the answer. I taught the band the songs in one day and recorded them the next, so we were finished in three days.”

In his autobiography (co-written with Victor Bockris), he writes: “Vintage Violence was basically an exercise to see if I could write tunes. There’s not too much originality on that album, it’s just someone teaching himself to do something…I thought the songs were simplistic. We were writing stuff that was very oriented to what the Band were doing, as the musicians on the album shared that same upstate New York country sensibility.”

More negatively, in the August 30, 1971 issue of Rock magazine, he impassively states, “It was a cop-out. I made the mistake of using other musicians. I should have gone in the studio and done the songs the same way I did Marble Index – overdubbing a lot, doing the parts myself, building the songs up the way I wanted. It would have been more interesting, more honest, more me. The songs on it are about things I’d thought about that morning. They all run into short stories I’ve written, the stories end up as maps and charts, lots of characters come out in my short stories. All of them have characters. Like ‘Adelaide’ is like an English rock and roll song. ‘Little White Cloud,’ like a Bee Gees thing. ‘Cleo,’ like old rock and roll.”

Vintage Violence is better than John Cale seems to think it is, although it’s not his most famous solo record, and still not all that widely known even to Velvet Underground fans, who’d likely pretty readily take a shine to it. I’m aware this list is pretty Velvet Underground-heavy, but then that’s a testament to the daring unpredictability of both the band and the solo work of their three most prominent members (Cale, Lou Reed, and Nico).

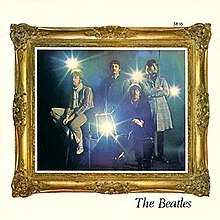

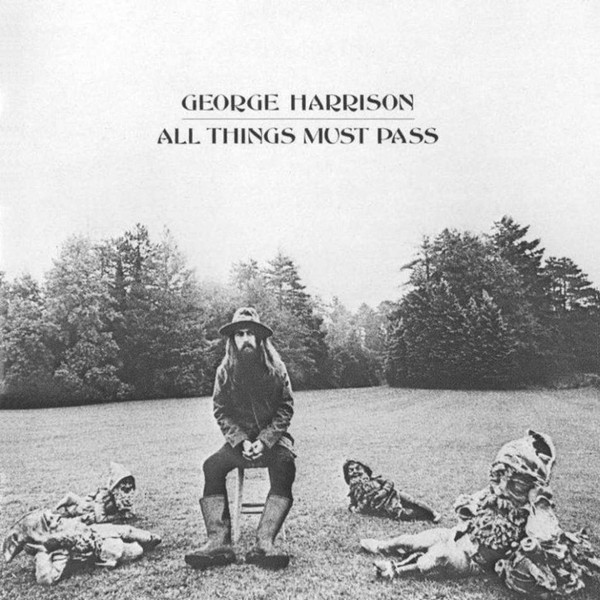

10. George Harrison, All Things Must Pass (1970). To fill out this Top Ten list to ten actual selections, I’ve taken small liberties. All Things Must Pass was not released or even recorded in the late 1960s, though it was on the market by late 1970, which isn’t that much later. Musically, it’s different from the Beatles or what George Harrison had done in the Beatles, but not hugely different. You can hear a lot of links between All Things Must Pass and the Beatles, and while it was different in notable ways—an increased emphasis on spiritualism in many compositions, a greater use of horns, and Phil Spector’s co-production (with George)—Harrison brought a lot of the Beatles’ melodicism to the songs, as well of course as his own singing and guitar playing.

In this case, the big surprise was not in the content, but in its reception. When the Beatles broke up in spring 1970, everyone was wondering how they’d fare as solo artists. If you’d polled people then as to who would do the best records on their own, I’m guessing about 99% of them would have said the contest would have been between John Lennon and Paul McCartney. As for the 1% who would have figured it would have been between George Harrison and someone else, not all of the 1% would have picked George as the winner.

So it was a huge surprise—and a pleasant one—that George’s true solo debut (not counting his Wonderwall soundtrack and avant-garde doodlings on Electronic Sound) outsold Paul and John’s debuts, and was the best record of the three. (Again, I’m not counting Lennon and McCartney’s various soundtrack/avant-garde/live LPs, and considering McCartney and Plastic Ono Band as their true solo debuts.) I realize quite a few listeners and critics would pick Plastic Ono Band as the best LP of this batch, and some prefer McCartney, though champions of Paul’s debut probably rank a distant third in this contest. In my view, however, All Things Must Pass was easily the best, and indeed the only solo Beatles album I’d rate on a par with the band’s releases. It would have been even better had George not put dull jams on disc three of the triple album, and instead used yet more of the songs he’d piled up (some demos of which are available on archival releases and bootlegs).

If there was any one good thing to come out of the Beatles’ breakup, it was that George was finally free to record—in the way he wished—all of the songs he had accumulated during the late 1960s, some of which (such as “The Art of Dying” and “Isn’t It a Pity”) had been written as far back as 1966. All Things Must Pass suggests that John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and George Martin not only underestimated Harrison’s songwriting talent, but also his production skills. As much as all Beatles fans lament the passing of the group in 1970, it’s impossible not to rejoice in George’s great triumph, surpassing the expectations of even his most devout fans—and, perhaps, even surpassing his own.