In late 2014, the release of a six-CD box set of Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes got some people thinking about major bodies of rock recordings that, for whatever reasons, were not released at the time they were made. And, in some cases, still aren’t released, or had to wait decades to be made officially available.

For those unfamiliar with rock history, the Basement Tapes might seem to be a singular event. Why would a top rock icon not put out music which he’d obviously invested a lot of time in, and which could certainly have been made into a releasable album had some more effort been put into the project when it was recorded? Was there some sort of one-of-a-kind accident involved, or some legal obstruction?

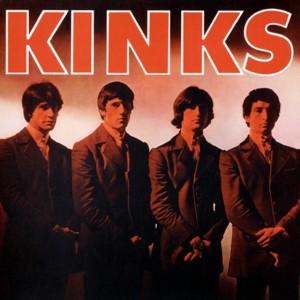

As it turns out, however, lots of artists from the 1960s and early 1970s had albums they didn’t put out, didn’t finish, or didn’t even start despite conceiving grand plans for them. In fact, it seems like almost every big rock act from the period had an unreleased album in their history, including the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Who, Kinks, David Bowie, and others. Not a few of them had more than one unreleased album or project that never came out, including Dylan himself. It’s almost like having an unreleased album was a rite of passage, or one more badge confirming your status among rock’s elite.

That did get me to thinking: what were the best unreleased albums of what we might call the dawn of classic album-oriented rock, from the mid-1960s through the early 1970s? Especially if we count not just unreleased albums that were actually finished and could have come out as-was (of which there actually weren’t too many), but also material from sessions that were working toward an album; live and demo recordings; and even projects for which not a note was recorded, but an ambitious album definitely envisioned?

What follows is my Top Ten list of such albums, ranked according not only to their quality, but also to their historical significance and the potential of their importance had they been completed and/or released. Certainly it doesn’t include every such record—there are at least fifty such things if you count artists of major and minor note, and no doubt thousands if you count everyone who recorded an unreleased album, or tried to. But it does have some of the most famous ones, as well as a few endeavors that might be unknown even to many big classic rock fans.

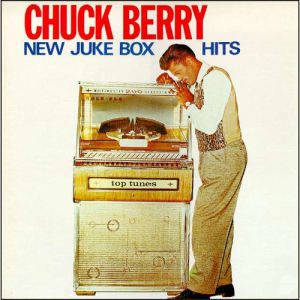

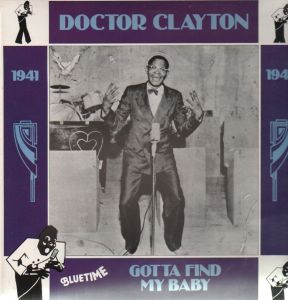

1. The Beach Boys, Smile

The top four albums on this list are, I would guess, identical to or close to the top four albums most likely to be selected by many fans and critics, though the order might differ according to the listener. Smile could well be the most famous of these, and—like each of the other three records—has even inspired a book, or at least (in the case of the Who’s Lifehouse) half a book.

So to reduce the epic story to a paragraph seems a bit minimalist, but here goes: after the Beach Boys’ 1966 masterpiece Pet Sounds, head Beach Boy Brian Wilson wanted to make a yet more ambitious LP, one that might have them challenge the Beatles’ position as the top band in the world. Many sessions were laid down in the last months of 1966, and the first few months in 1967, that found Wilson (and, at least as participants in the sessions, the Beach Boys) venturing into territory far more avant-garde than any they or most of their peers had explored. For many reasons, including Wilson’s increasing instability; frustration that the Beatles and other competitors were moving ahead while the project foundered; reluctance of the other Beach Boys, particularly singer Mike Love, to follow Wilson’s visions; and disorganization that hindered the tracks’ completion, the album was abandoned in 1967.

Almost immediately, some excerpts from the sessions appeared on Beach Boys records; the #1 1966 single “Good Vibrations,” after all, was part of them, as was the smaller hit “Heroes and Villains.” Starting in the early 1980s, bootlegs of unreleased sessions appeared, some of them attempting to simulate what might have been Smile’s contents and running order. In 2011, an official box set, The Smile Sessions, finally appeared, one of the discs being a more or less official version of what the album would/should have sounded like.

My own feeling is that the best of the Smile sessions—including not just the most accessible songs a la “Good Vibrations,” but also some of the most structurally daring and experimental—are glorious, especially in those sections incorporating melodies of almost classical beauty, and vocal harmonies as daring in their sophistication as almost any in pop music. Yet I also feel that the tracks would not add up to an album comparable in worth to the more concise, focused Pet Sounds. And, despite the officially sanctioned version of Smile, they never sound to me like something that A) was totally finished or B) would add up to the most coherent whole. And some of the humor, which was an important ingredient to the project, is pretty corny and not-so-funny.

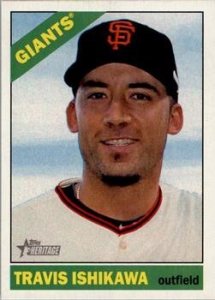

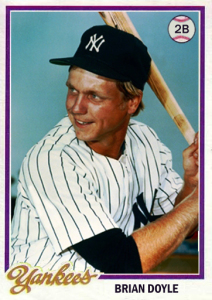

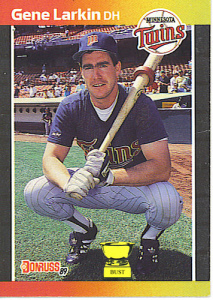

The “new improved” 1985 version of the Beach Boys’ Smile bootleg, with liner notes by “Nancy Reagan.”

Also, I never felt as if the official version, or the many unofficial simulations, got the track sequencing or “final cut” selections right. It’s strange when some Smile bootlegs I’ve heard seem to have a better flow than the official 2011 one, but that’s how it comes off to me. In part that’s because it, like most of the records listed here, actually was never finished. Had it somehow been seen through to completion back in 1967, probably all sorts of things would have been different, from the running order and song selection to the mixes.

Still, Smile, for all its warts, is the Beach Boys—and it is a Beach Boys record, not a Brian Wilson solo project—aiming for their highest heights, and sometimes coming close or succeeding. Indeed, it’s pop-rock as a whole aiming for its highest heights, and sometimes coming close or succeeding. For those reasons, it is the most significant unreleased album of all time, if one that never quite captured what Brian Wilson had in mind, perhaps because its scope might have been beyond what mere humans could attain.

2. The Beatles, Get Back

The Beatles were working toward an album that would have been called Get Back in January 1969. But like Smile, the tapes recorded for it (and subsequently bootlegged, perhaps more than any other body of recorded work) were more an accumulation of sessions than a completed LP. And, by the Beatles’ matchless standards, Get Back wouldn’t have been one of their best albums, or even one of their better ones, although it did have some great songs, like “Let It Be,” “Don’t Let Me Down,” and “Get Back” itself.

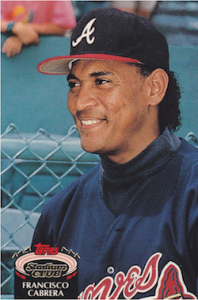

The Beatles got as far as taking a picture in early 1969 for a projected Get Back album, whose cover (subtly re-creating/satirizing the photo and cover designed used for their first LP, Please Please Me, in 1963) probably would have looked something like this.

For even more reasons than Smile, Get Back never appeared. The Beatles were unhappy with the January 1969 sessions in general, never really agreeing on whether they should be assembled into an LP, or how they should be assembled into an LP. The project was hindered by simultaneous plans to film a documentary of the sessions (to become the Let It Be movie) and return to live performance (an idea that George Harrison in particular nixed, though they did so, in a limited way, on the Apple headquarters rooftop concert that concludes the film).

Had they pulled off what was originally planned—getting back to their roots by recording live without overdubs, and even making the album a concert LP comprised of wholly live performances of new material—Get Back would have been quite interesting. Or great, had all the songs been as great as “Get Back,” “Don’t Let Me Down,” and “Let It Be.” But with material that was more good than great, and a lack of enthusiasm (and even fighting) within the group, the Beatles couldn’t summon the will to polish it off. Abbey Road came out before the Beatles, or some of them, enlisted Phil Spector to produce an album drawn mostly from the sessions, Let It Be, which in turn would finally push Paul McCartney to announce his departure from the band.

There were versions of Get Back that probably came close to getting released, particularly on acetates cut by engineer/producer Glyn Johns that were subsequently bootlegged. There was even a cover shot for the album, originally planned for early 1969 release before getting delayed, and before Abbey Road took precedence. It’s not the best Beatles, but even imperfect Beatles is better than almost anything else. And, because it’s the only close-to-unreleased-album of sorts in the catalog of the best rock group of all time, it’s one of the most important unreleased albums by anyone, even if it doesn’t quite make #1 on my list.

The Get Back sessions are thoroughly described and analyzed in this book.

I wrote much more extensively on the Get Back”sessions in my book The Unreleased Beatles; Music and Film.

3. The Who, Lifehouse

Lifehouse is a little different than Smile and Get Back, as by the time sessions including the material got underway in earnest, plans were waning (and then abandoned) for the ambitious album that was the original intention. If not the intention of the Who as a whole, it was certainly the intention of principal songwriter Pete Townshend, who wanted to make a concept/story album of sorts after the success of 1969’s rock opera Tommy. In some respects, Lifehouse would have been more ambitious, incorporating more media than just sound recording and performance.

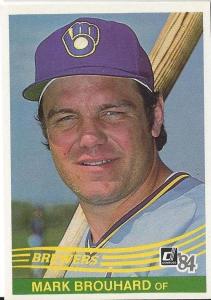

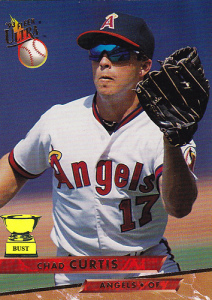

This bootleg of Lifehouse material uses an outtake from the photo session for Who’s Next on the cover.

A much fuller back story, if I may advertise myself for a minute, is in my book Won’t Get Fooled Again: The Who from Lifehouse to Quadrophenia, which covers the Who’s career in the early 1970s, focusing on their Lifehouse and Quadrophenia projects in particular. But to boil down an impossibly complicated scenario to a few sentences, Townshend envisioned a rock opera of sorts built around a future in which the population, in the wake of environmental devastation, is controlled by a totalitarian government that doles out necessities accessible by “experience suits.” Rebels in opposition to the regime plan and stage a rock concert in defiance of the authorities. At the concert, performers (probably the Who) and audience merge into one and transcend the trials of this bleak world into a more enlightened state.

But Lifehouse wouldn’t just have been an album (probably a double album, like Tommy was). It would also have been a movie, probably starring the Who, and probably incorporating actual concert sequences. And Townshend and the Who, he hoped, would get inspiration by workshopping the material in front of real-life audiences, whose feedback and participation would provide grist for songs, and whose personalities could even be converted into patterns that could be programmed through synthesizers.

It was all too much for even the supportive fellow Who members to handle, or even understand. After some aborted sessions in New York in March 1971, the Who started their next album back in London. Under the advice of engineer/producer Glyn Johns, it was determined to scrap the double-LP concept idea (which in truth was on the verge of being abandoned anyway) and concentrate on an album of unconnected songs. Most of the songs selected for that album, 1971’s Who’s Next, had indeed been written for Lifehouse, but it didn’t add up to a story or opera, and many Lifehouse songs were not included.

You could make a good argument for switching the order of Lifehouse and Get Back on this list, as the Lifehouse songs that did make it onto Who’s Next were considerably more significant to the Who’s career than the Get Back material was to the Beatles’. The failure of Lifehouse to exist in even an approximately finished album (as Get Back did), however, is a strike against it, and the Beatles’ status as the #1 rock group (though the Who rank up near the top) a blow in favor of Get Back.

There’s much more information about Lifehouse in my book Won’t Get Fooled Again: The Who from Lifehouse to Quadrophenia.

Had Lifehouse been completed, it would have been the realization of one of rock’s most ambitious projects, bar none. It didn’t get completed, however, for some of the same reasons Smile didn’t: it bit off more than it could chew, and it never really got organized into a coherent sequence of songs. In addition, not many people point out another flaw in the enterprise: the best half of Lifehouse’s songs (most of which would make Who’s Next) are, with a few exceptions, far, far superior to the worst half of Lifehouse’s songs (most of which have come out, in dribs and drabs, on various Pete Townshend solo projects and Townshend/Who archival releases).

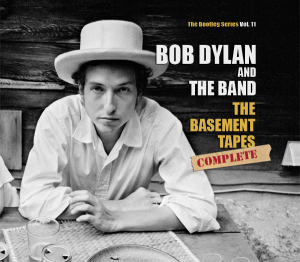

4. Bob Dylan, The Basement Tapes

Plenty of critics, and some fans, would put these recordings—which have actually “come out” in several iterations—at #1 on this list, not #4. Some might even judge it one of the greatest bodies of recorded work of all time, not just one of the greatest bodies of unreleased work. Some have certainly championed it as one of the most influential in its rebuff of psychedelia for eccentric roots rock. At the time they were recorded in 1967, though, their influence was mostly limited to acetates of a dozen or so of the best songs, which were passed around to some other artists to hear and sometimes cover (and which were bootlegged, though not immediately).

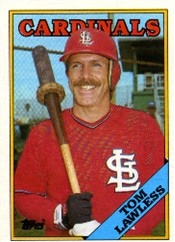

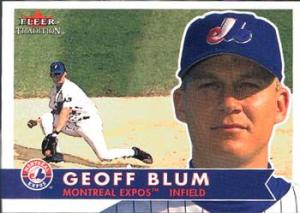

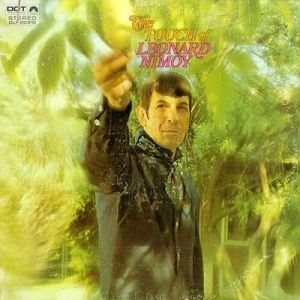

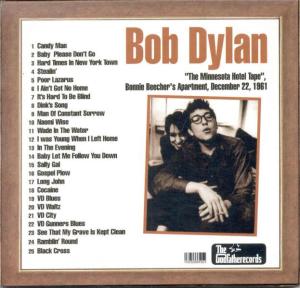

One of many bootlegs of the Basement Tapes, now made obsolete by the 2014 release of The Basement Tapes Complete.

To reprint what I wrote in my mini-review of the six-CD box set The Basement Tapes Complete: The Bootleg Series Vol. 11 in my list of top ten reissues of 2014 (where I also placed it #4, as it happens):

“While I don’t find this as godhead as many critics and Americana bands do, this six-CD box rounds up everything usable known to have survived from the quirky 1967 recordings Dylan made with the Band. This found the musicians working counter to most trends in rock music that year, mixing folk, country, blues, gospel, and rock’n’roll on idiosyncratic original Dylan material (sometimes written with help from Band members). They also ran through many covers, some quite obscure, though these have a rather loose, informal warm-up feel. So do some of the originals, many of which seem casual toss-offs or frustratingly incomplete. The most fully formed and celebrated songs—generally, the ones that also appeared on the 1975 Basement Tapes double LP—are available on a two-CD distilled version of this box, The Basement Tapes Raw.”

A whole three months later, my opinion’s unchanged. If you want a much longer review I wrote of the box set, it’s in the winter 2014 (#6) issue of Flashback magazine. Part of it offers an assertion I realize will not be universally popular among Dylan devotees:

“The basement tapes that were recorded and eventually excavated have often been hailed as a necessary antidote to the indulgent psychedelia that was threatening to remove rock music from the roots that had made it such a potent force since the mid-1950s. That’s one view, but it can also be fairly observed, I think, that if Dylan was deliberately turning his back on psychedelia, he was also missing out on a lot of exciting innovations. The Basement Tapes might have a more straightforward, no-nonsense approach than Sgt. Pepper, The Doors, and Surrealistic Pillow, but it doesn’t match the peaks of those albums either, or even the peaks of Dylan’s more recklessly risky mid-‘60s electric LPs. Canonizing the Basement Tapes as the sessions that brought rock back to its senses again and pointed the proper way forward, as a number of past and recent critics seem to do, seems to me a thoughtless dismissal of much great music of the same era, and an inaccurately revisionist distortion of the Basement Tapes’ actual impact and significance.”

If you want to read a book-length history of the Basement Tapes by a respected musician and critic who likes them more than I do, I recommend Sid Griffin’s Million Dollar Bash: Bob Dylan, The Band, and the Basement Tapes. Whatever one’s opinion of the material, it would be interesting to know what effect they might have had if the best of the material had been officially released as a single or double LP back in late 1967 or early 1968, whether instead of or in addition to the Band-less Dylan LP that did appear, John Wesley Harding. But that’s one question we’ll never have answered.

Sid Griffin’s book Million Dollar Bash has a wealth of info about the Basement Tapes.

5. The Velvet Underground, The Lost Fourth Album

Here we reach a group of songs that, unlike the previous four, don’t seem to have been recorded with a specific purpose in mind. Even the Basement Tapes served the function of getting Dylan back into music-making after his 1966 motorcycle accident; getting some compositions into circulation for other artists to cover, which he said at least once was the motivation behind their creation; and working on some new material with the Band. And the recordings that resulted did get a name, even if they didn’t come out in any album form until the mid-1970s.

In contrast, the tracks that Velvet Underground recorded for MGM in the studio in 1969 just seemed like a stack of random sessions, rather than something intended to be grouped into an LP. They never did get a name, even though all the known ones have come out on archival releases, beginning with the 1985 outtakes compilation VU (some had been bootlegged earlier). They’re not even colloquially known as “the lost fourth album”; each of these entries needs a title, and that’s about the best one I could come up with.

“Foggy Notion” was one of the songs recorded by the Velvet Underground in 1969 for their possible “lost” album.

But considering the Velvets’ status as one of the greatest bands of the ‘60s, and one that (unlike the previous four artists on this list) didn’t release that many albums, any grouping of unreleased songs recording within a five-month or so period is significant. And between May 6 and October 1, 1969, they cut about 15 songs—enough to make an album with a little left over. As I wrote in my book White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day-By-Day:

“What would a fourth MGM Velvet Underground album have included, had the label released it? Four decades later, we can only guess, but the tracklisting might have been something like this: ‘Rock & Roll,’ ‘Ocean,’ ‘Lisa Says,’ ‘One Of These Days,’ ‘She’s My Best Friend,’ ‘I Can’t Stand It,’ ‘We’re Gonna Have A Real Good Time Together,’ ‘Andy’s Chest,’ ‘I Found A Reason,’ ‘Foggy Notion,’ ‘Ride Into The Sun,’ and ‘I’m Sticking With You.’ It might not have been a record as good as the first three VU LPs, but it would still have been a pretty good one, and perhaps even better than that, had the group later added some of their newer songs from the fall of 1969 [as heard on live tapes from the time], such as ‘New Age’ and ‘Sweet Jane,’ to the mix.”

The material was generally lighter and more good-natured in tone than their first three albums, leading to speculation that perhaps they were saving their best new songs for an album that would appear on another label. As I also wrote in White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day-By-Day:

“[VU manager] Steve Sesnick might [have] already [been] maneuvering, as he later claim[ed], to get the band off MGM; maybe the band in turn [were] walking the fine line of making it look like [they were] working on a record, but making sure the recordings [weren’t] in good enough shape to be released. And yet Sterling Morrison [would] later claim to have been under the impression that the Velvets were working on a fourth album, while as Maureen Tucker puts it in the Peel Slowly And See [box set] liner notes: “As far as I knew, and know, we were making a record. I also believe we were trying to get out from MGM. I don’t know what the plan was. Maybe it was just to not finish it enough. Some of those tracks don’t even have [finished] vocals on them. Maybe we were doing it just to keep them from saying ‘We need a record!’ I’m sure the way we did all those tracks had to do with trying to get away from MGM.”

There’s more info about the VU’s “lost” fourth album in my book White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day-By-Day.

What the Velvets and MGM were planning with this album of sorts—and how the Velvets managed to get off MGM and sign to Atlantic to do their 1970 album Loaded, despite having signed a contract to MGM running through May 1, 1971—remain among the more interesting unsolved mysteries of 1960s rock. At least the 1969 recordings themselves are no longer a mystery to the public; all of the known ones are on the super-deluxe box set edition of their third album, as well as getting strewn (sometimes in different mixes) throughout other archival releases.

All of the known 1969 studio recordings that might have been considered for the Velvet Underground’s “lost” album are on this deluxe edition of their third album, which was simply titled The Velvet Underground when it came out in early 1969.

And as some consolation, a double album of live unreleased recordings from late 1969, including some versions of songs they’d cut in the studio earlier that year, did come out in 1974. And that double LP, 1969 Velvet Underground Live, is not just one of the greatest Velvet Underground records, or one of the greatest concert records, but one of the greatest records by anybody. So what the Velvets were up to in 1969 was pretty much properly documented, and reflected better by these live recordings than their studio ones of the same year, even if it took five years for 1969 Velvet Underground Live to get released.

6. Jimi Hendrix, First Rays of the New Rising Sun

In late 1968, just a couple years into his career as a bandleader, Jimi Hendrix issued his third album, Electric Ladyland—a double LP, no less. He’d have about two years left to live, but he never did manage to put out another studio LP, although his 1970 concert album Band of Gypsys did include some new original material. The absence of a new studio album was all the more frustrating given that he recorded prolifically during this period. Yet he couldn’t seem to get it together to finish the record, decide on the running order, conclude his tinkering with the tracks, and so forth.

Much confusion continues to hover over what Jimi Hendrix would have issued as his fourth studio album, and indeed over what it would have even been called. As early as a January 1969 BBC interview, he announced two albums that were in the pipeline, one to be called Little Band of Gypsys (presumably the origin of the name of his Band of Gypsys group in late 1969) and the other First Rays of the New Rising Sun. “The Americans are looking for a leader in their music,” he declared. “First Rays of the New Rising Sun will be about what we have seen. If you give deeper thoughts in your music then the masses will buy them.” By contrast, Little Band of Gypsys, he told NME, would be a “jam-type” affair.

Although it’s thought that the fourth album would have most likely been a double LP, in fact Hendrix had enough material by the summer of 1970 to consider a three-disc set. Typically of his mindset in his final days, however, he couldn’t decide on either which songs to include or the size of the release. Even the title was uncertain, with People, Hell and Angels and Straight Ahead also under consideration.

Hendrix did compile a handwritten selection for three LP sides of First Rays of the New Rising Sun that surfaced in 1994, and was reprinted in the November 1994 issue of the French magazine Folk & Rock. This would have gone as follows:

Side A: “Dolly Dagger,” “Night Bird Flying” (though he wasn’t totally sure where to place this), “Room Full of Mirrors,” “Belly Button Window,” “Freedom”

Side B: “Ezy Ryder,” “Astro Man,” “Drifting,” “Straight Ahead”

Side C: “Drifter’s Escape,” “Coming Down Hard on Me,” “Beginnings,” “Cherokee Mist,” “Angel.”

While an album titled First Rays of the New Rising Sun was assembled from these sessions and released on CD in 1997, it’s important to note that this was not a ready-to-go record that Hendrix had finished, but an approximation of what it might have sounded like and which songs would have been selected. No such record could be posthumously compiled, as no one knew with absolute certainty what songs he would have included, and what additional production work he might have done on the ones he’d laid down in the studio, no matter how complete they might have seemed to others. It doesn’t even follow the order, even approximately, of his handwritten list for three LP sides, and doesn’t include some of the songs from that list (such as “Drifter’s Escape”), adding a few (like “Stepping Stone”) that were not on his list:

If there’s to be a collection of such material, however, First Rays of the New Rising Sun is undoubtedly the best one that’s yet been produced. At 68 minutes, it’s considerably longer than the ten-track LP from March 1971, The Cry of Love, that represented the first attempt to make something of these sessions. First Rays of the New Rising Sun has all ten of the songs heard on The Cry of Love and adds seven more, including a few of the more notable ones from this era, such as “Room Full of Mirrors,” “Dolly Dagger,” “Stepping Stone,” and “Izabella.” And it (as well as The Cry of Love) is certainly preferable to the similarly intended 1995 CD Voodoo Soup, which had less songs and new overdubs by Knack drummer Bruce Gary on a couple tracks.

More important than the packaging and speculation as to what Hendrix was up to, however, is the music. And though it inevitably doesn’t hang together as well as his three actual studio albums, or contain material quite as impressive, First Rays of the New Rising Sun does offer what for the most part are decent songs with imaginative production, often with a more upbeat mood than you’d expect given the reports of his internal anguish in his final days. “Angel” and “Dolly Dagger” are the standouts, but there’s some welcome cosmic humor and wistfulness in “Astro Man” and “Belly Button Window,” and generally pleasing uplifting spiritual qualities to some of the rest without forsaking his blues-rock base. Some of the tracks nonetheless skirt nondescript blues-rock or riffs that haven’t quite fully developed into songs, but in hindsight this collection offers hope that Hendrix was easing his way back toward discovering his songcraft without abandoning his technological wizardry.

This isn’t a complete overview of the songs Jimi was working on post-Electric Ladyland, missing, for instance, “Message to Love,” which he was featuring in concert. If it’s considered even an approximation of his fourth album, there’s also a slight sense of letdown in that there isn’t nearly the sense of creative advancement as there’d been with each of the LPs he did with the original Experience. It’s a highly worthwhile encapsulation of his final group of studio outings, but it’s not on the level of Electric Ladyland or Are You Experienced?

A common thread that runs through several of these albums—Smile, Get Back, and Lifehouse—is a seeming inability to complete or follow through on an album blueprint that had obvious promise, or possible genius. Perhaps these failures were attributable to some combination of over-perfectionism, self-doubt as to the worth of the material, or inability to stick to the original concept. Hendrix’s fourth album might not have had as definite a concept as the above-mentioned trio of records, but likewise seems to have fallen prey to some of the same difficulties.

The book Black Gold goes into detail not on the material recorded for The FIrst Rays of the Rising Sun, but all of Hendrix’s unreleased material.

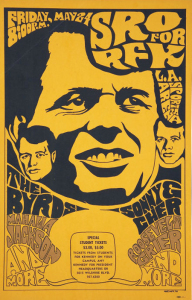

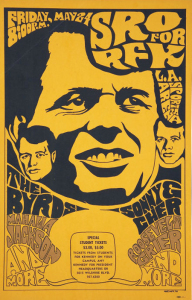

7. The Byrds, Unrealized 1968 Double-LP Concept Album on the History of 20th Century Music

I realize the above title sounds like a put-on, but though this project was never titled, Byrds leader Roger McGuinn did want to make a record like this. It’s unlike any other item on this list in that there’s no actual unreleased album of music associated with the concept, or even sessions of unreleased music associated with the concept. It is, however, to me the most interesting of ideas for albums by major bands that were at least discussed and considered, but never actually embarked upon, let alone completed. Here’s the story:

For the Byrds’ follow-up to The Notorious Byrd Brothers—their fifth album, and their last done with David Crosby, who was fired partway through its recording—McGuinn had planned an ambitious double album that would cover no less than the entire history of twentieth-century popular music. As McGuinn noted in Johnny Rogan’s massive biography Byrds: Requiem For the Timeless: Vol. 1, “It was going to be a chronological thing. Like old-time bluegrass, modern country music, rock’n’roll, then space music. It was meant to be a five-stage chronology.”

Adds Rogan in the book, “McGuinn spoke about his plans, confident that he had the full consent of the other members [who were, at that point, original Byrd bassist Chris Hillman, new drummer Kevin Kelley, and new singer/guitarist Gram Parsons]. They planned to cut 25 or 30 tracks, culminating in a double album which he promised would be released by early summer [1968].” A small sampling of what the final leg of that journey might have sounded like, the outtake “Moog Raga,” was eventually issued more than 20 years later. There was no rock or country in this instrumental experiment by McGuinn to fuse Indian ragas with the latest (although it now sounds primitive) in synthesizer technology.

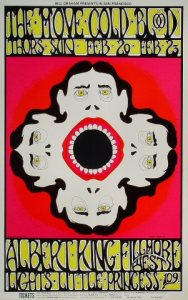

Unusual poster for a Byrds concert at a benefit for presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy on May 24, 1968, less than a couple weeks before he was assassinated.

His double-album dream would be unfulfilled, however, as both Hillman and David Crosby’s replacement, Gram Parsons, lobbied successfully for an all-out country album. “That was more Roger’s deal,” Hillman told me [when interviewed for my book Jingle Jangle Morning: Folk-Rock in the 1960s] of tracks like “Moog Raga” and Younger Than Yesterday’s “C.T.A.-102,” which had matched another proto-country-rock track with weird electronic simulations of space alien voices. “I would play on it, but it wasn’t something I was involved in, other than as the bass player. He had that side of him, musically, that was not my style of music. It really wasn’t something that I loved that much. But I was a player, and that’s his piece of material, so I supported it. But I sort of dragged him into the country stuff, so it works both ways. And he performed quite well with that [country] stuff.”

Hillman, unlike McGuinn, has no regrets that the double-album history of twentieth-century music never happened. “With all due respect, I didn’t want a bunch of ‘C.T.A.-102’s or ‘Moog Raga’ or whatever that stuff is. He had that Moog synthesizer; then, it was like owning a computer in 1955. It took up the whole room. It made a lot of noise. It wasn’t really musical. It was like a toy, a gadget. But it was interesting. I respect him; he was following something that intrigued him, and he likes electronics.

“It didn’t work for me, and I’m glad it didn’t happen. ’Cause it would have made no sense at all. Although there weren’t that many strong parameters then; you could sort of do those kind of projects, record company budget willing, on that end. But to put the two of them [traditional and electronic styles] together would have been a little crazy. It would have been an interesting separate project, but either I didn’t understand what he was doing, or I just didn’t like it. I’m glad we did the Sweetheart [of the Rodeo, the 1968 country-rock LP they recorded instead] as it was.”

“I couldn’t get anybody to support me on that,” acknowledged McGuinn when I interviewed him for the same book. “Chris was behind Gram, and Gram wanted to do straight country, and that was it. It would have been fun if we could have pulled it off. I agree it was extremely ambitious, and it’s almost doubtful that we could have done it. But I would love to have tried, at that time. Basically, we did do it, not just in one album, but in a series of albums. We’ve done old-time music, and almost every genre you can think of.”

Single with a couple outtakes from Sweetheart of the Rodeo, the album the Byrds recorded instead of Roger McGuinn’s ambitious two-LP history of twentieth century music.

Here’s one of my many opinions that isn’t universally popular, especially considering that Sweetheart of the Rodeo is considered a groundbreaking classic by some: I wish the Byrds had done McGuinn’s concept album instead. I think it would have been much more interesting. As for Roger’s comment that the Byrds did do it over a series of albums, that reminds me a little of Lou Reed’s comments that if you wanted to hear what the Velvet Underground would have sounded like had the John Cale-Nico lineup stayed together longer, you could hear it spread over Reed, Cale, and Nico’s solo albums. There was some good stuff on those records, but it wasn’t nearly the same as having all the musicians play it at once in concentrated doses.

Likewise, the Byrds covering all of this territory over the course of one double-LP concept record seems much more interesting than spreading it over the course of several albums recorded by different lineups. It might be, however, that the early-’68 Byrds lineup wasn’t suited for this experiment, especially as Gram Parsons (and Chris Hillman) really wanted to do country music instead of messing around with all that other stuff (especially the electronics). The previous lineups that did their 1966 and 1967 recordings were really the ones that could have handled it. But some of the same tension that drove the Byrds’ greatness during those years also pulled them apart, and since the tension between Crosby and the other Byrds in particular was so great, it’s hard to imagine that he could have stayed with them for even the six additional months or so necessary to launch this double LP.

8. Bob Dylan, Live May 17, 1966

As many of you reading this no doubt know, this was officially issued in 1998 under the awkward title The Bootleg Series Vol. 4: Bob Dylan Live 1966: The “Royal Albert Hall” Concert. As many of you doubtless also know, this wasn’t actually recorded at the Albert Hall, but in Manchester. The “electric” half of it was, however, for many years bootlegged as an Albert Hall concert. Who knows what it might have been called had it actually been released in 1966 or 1967. It certainly wouldn’t have been given its 1998 title, however, the bootleg series (and rock bootleg LPs) not yet existing back then.

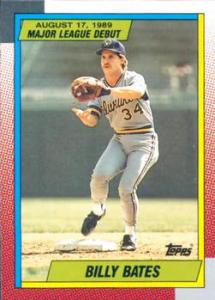

The official release of Dylan’s May 17, 1966 concert.

Unlike every other item listed here, this recording has officially come out in its complete form—not in an abridged version, a reconstructed one by the artist, or guesses as to what the track selection/mixes/sequences might have been. For that matter, it adds more material, putting the “electric” rock part of the concert (with the Hawks, later to evolve into the Band) on one CD, and the solo acoustic part on another. The sound quality on the electric part’s better than the bootlegs, especially on the opening “Tell Me, Momma.” A win-win situation for fans, then, other than having to wait 32 years for its appearance.

So what’s it doing here, if it’s easily available in all its splendor? Well, for many years, it was a hugely significant missing piece of Dylan’s oeuvre, and not only because of the quality of the music. It was the only relatively hi-fi document of the most controversial juncture of his career, when he moved from folk to not just folk-rock, but loud rock. There were other live recordings from major ‘60s acts that were not released at the time, and have since been issued or heavily bootlegged: the Beatles’ Hollywood Bowl shows, the Rolling Stones Liver Than You’ll Ever Be from the 1969 US tour, the Who’s 1968 Fillmore East concert, and the Velvet Underground’s live gig at the Gymnasium in 1967. But none are as of comparable importance, both within the career of the artist and in the history of rock itself, as this one.

The story behind this concert is more well known than the histories of most of the items in this post, so here are a couple bits that aren’t so well known, from Paul Cable’s 1978 book Bob Dylan: His Unreleased Recordings. As to how the electric half got into circulation and bootlegged in the first place, he writes, “Legend has it that a young man greatly impressed with the concert simply wrote to CBS to ask them if they would send him a tape of it. According to the legend, they answered him most mysteriously—i.e., they sent him a tape—and the rest is history.” Also, in the brief period in 1973 and 1974 when Dylan left Columbia for Asylum, “There was a widespread rumor that Columbia were all set to release an entire ’66 gig as their follow-up to [the 1973 outtakes collection] Dylan. It has also been suggested that by the time they got Dylan back they had got as far as printing the covers.”

A couple of the many bootlegs of material from Dylan’s May 17, 1966 concerts, which usually misidentified the location as the Royal Albert Hall.

Cable also points out that had Columbia been waiting for a chance to put out this May 17, 1966 recording (or many other unreleased Dylan tapes that could have been considered) when it didn’t conflict with one of his new albums, “The rainy day came—two lots of rainy days came. On the first occasion [in 1967, when Dylan withdrew from the music business for about a year and a half following his mid-1966 motorcycle accident] they put out Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits and on the second occasion [when Dylan left Columbia for Asylum in 1973] Dylan. Strange, isn’t it?”

9. Dave Davies, Hidden Treasures

Here’s another case in which a legendary unreleased album has come out—though it’s probably not exactly in the shape it would have taken back in 1969, and in fact the shape it would have taken isn’t really known, since it wasn’t really completed. Kinks lead guitarist Dave Davies had occasionally sung and written Kinks songs since the group started, and in 1967 vaulted into greater prominence when a track from the band’s Something Else By the Kinks album, “Death of a Clown,” became a big UK hit when released as a Dave Davies solo single. A few other Davies solo singles followed in 1968 and 1969, one of which, “Susannah’s Still Alive,” was a mid-size UK hit. In late 1968, plans were made to make a Dave Davies solo album, though in a way it would have been a Kinks side project, since the Kinks backed him on his “solo” tracks. More or less enough material was completed for (when combined with previously released singles) an entire LP, but it didn’t come out.

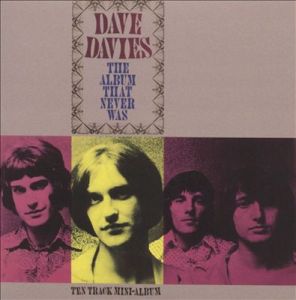

The Hidden Treasures album contains most or all of what would probably have come out on Dave Davies’s 1969 solo album, along with a lot of extra material.

Understandably considering principal Kinks singer/songwriter Ray Davies’s talents, Dave didn’t get nearly as much space on the band’s releases to sing lead and present his own compositions. But the tracks on which he did were nice complements to Ray’s brilliance, Dave delivering earthier, quirky, usually wistful songs with a voice so much coarser than Ray’s that you wouldn’t suspect they were brothers. Dave’s songs sometimes had a pretty folky bent, too, that sometimes verged on rustic, though he could still unleash some of the ferocious guitar work for which he was most renowned, as he did on the wobbly Hawaiian lines on the 1969 B-side “Creepy Jean.”

On July 2, 1969, a tape was submitted to Warner Brothers that contained most of the tracks from Dave’s solo singles (and one, “Mindless Child of Motherhood,” that came out on a Kinks B-side). It also had a few that hadn’t been released anywhere, among them a couple Ray Davies compositions that Dave sang. It was kind of a hodgepodge, but did still altogether make for an interesting showcase of Dave’s talents as a singer and songwriter. Some of the unreleased tracks were pining, yearning ballads (“Crying,” “Do You Wish to Be a Man,” and “Are You Ready”) that Dave has said, in retrospect, reflect his unhappiness at being pressured to make an LP when he was unsure of whether he wanted to do so. He also had mixed feelings about putting out solo records when he was so committed to the Kinks. This could explain the nonappearance of the LP (which never got a title), to the disappointment of fans who wanted to hear more of what he had to offer as a frontman.

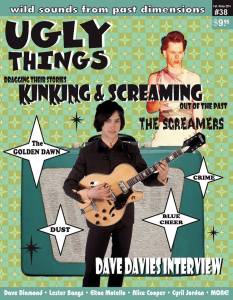

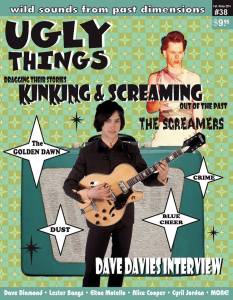

“I think Robert saw it as a way of me getting my own solo career going,” he told me in a 2014 interview (printed in full in the fall/winter 2014 issue—issue #38—of Ugly Things). “But the strange thing was, I never really wanted to have a solo career. I thought on that first album that I did, after ‘Death of a Clown’ and ‘Susannah,’ I felt like I was being forced to do something that I didn’t really want to do. And that’s why that first album was half-hearted, because my passion, my heart wasn’t in it.” In addition, “I didn’t like that studio at Polydor [where sessions were recorded for the album]. The Kinks had been recording in these lovely Pye [Records] studios, and I thought they were kind of undermining me.”

Added Dave, “I think [Kinks co-managers] Robert [Wace] and Grenville [Collins] did realize that I could have been a solo artist in my own right. But I was so bloody attached to family. I felt it was important for me to be around to support Ray and help the music. And I didn’t really feel that comfortable being out on me own that much. I think that comes from growing up in a big family. You’re in a family, and then you’re in the public eye. It seemed like the audience were just an extension of your own family. It was like I had this family thing all inside me, and I didn’t feel at that time comfortable being out in the front all the time.”

My entire interview with Dave Davies is in the fall/winter issue (#38) of Ugly Things.

Interestingly, one of the Kinks’ managers felt Dave had considerable potential as a solo artist in the US. “The Kinks have been recording a lot of new material for the last few weeks and you will have a new album by them within the next ten days, also an album which will feature Dave Davies as a soloist backed and accompanied by the Kinks,” wrote Robert Wace to Reprise Records executive Mo Ostin on June 18, 1969. “I feel that this could be a particularly successful album and should probably be released after they have been in America or around the time that they are there, because although I have not heard all the material, Dave’s approach seems to Reprise Records be more underground than the Kinks. They are very excited about the possibility of getting into America in September, and I do hope that Warner Bros. are going to give us the support that we need.”

It’s odd that Wace felt “Dave’s approach seems to be more underground than the Kinks.” Without denigrating either the Kinks’ output or Dave’s solo output in the least, it’s hard to judge one as being more “underground” than the other. And when Wace wrote his memo, the Kinks didn’t need a Dave Davies solo record to cement their status as an underground act—their records hadn’t done well since 1966, and their Stateside following was being kept alive by a fanatically dedicated cult of fans and critics.

The unreleased album did finally come out—though the unreleased tracks among these had long been bootlegged, in lower fidelity—in 2011 on Hidden Treasures. It’s surprising how little attention that CD got considering its historical interest, appearance on a major label, and—most importantly—high quality. Note that it’s not exactly the album that would have appeared in 1969, whose track list was probably never finalized anyway. The CD expands whatever-the-album-would-have-been to 27 tracks by adding most of the Dave Davies compositions from mid-to-late-‘60s Kinks releases, including such highlights as “I Am Free,” “Love Me Till the Sun Shines,” and “Funny Face,” as well as less essential mono versions; a demo of “Hold My Hand” that only came out on a Dutch compilation; and the 1967 outtake “Good Luck Charm,” a cover of a Spider John Koerner good-time blues number. Taken as a whole, it’s an eminently worthy summation of Dave’s 1960s recordings on which he took the spotlight as singer-songwriter—a talent that was sadly underutilized, both at the time and on post-‘60s Kinks releases.

Some, but by no means all, of the material that would have appeared on Dave Davies’s 1969 album was on this 1987 compilation LP.

10. David Bowie, Early 1969 Demo Tape

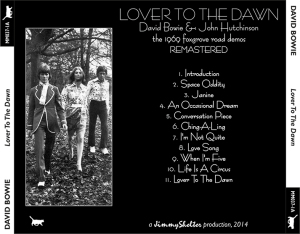

Not a very descriptive name, I know. But it’s still unclear exactly when, where, or for what purpose this ten-song demo tape was made, though Kevin McCann dates it as having been done on March 8, 1969 in his book David Bowie: Any Day Now: The London Years: 1947-1974. The purpose was almost certainly to arouse record company interest in the between-deals Bowie, and probably specifically meant for Mercury Records, which did sign David.

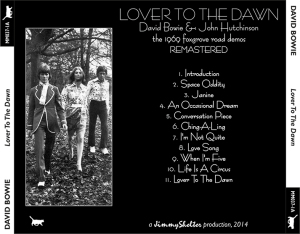

Bootleg LP that contained nine of the ten songs from David Bowie’s early-1969 demo tape, missing “Lover to the Dawn.”

Unusually, this captures Bowie at a point in his career where he was a folky, or at least folk-rocky, singer-songwriter. As hard as it might be to believe, he—with backing by second guitarist/harmony singer John Hutchinson—sounds something like a British Simon & Garfunkel here. The songs, of course, are quite different from those of Paul Simon even at this early stage in Bowie’s development, and include acoustic versions of highlights from his 1969 and 1970 releases like “Space Oddity” (with a primitive Stylophone effect), “Conversation Piece,” “Janine,” “Letter to Hermione,” and “An Occasional Dream,” the last of which is one of the greatest unreleased Bowie performances (and most overlooked Bowie songs, period) of all.

Other songs aren’t as impressive, and some, particularly “When I’m Five” and “Ching-A-Ling,” are kiddie-like leftovers from his overly theatrical phase. But even the minor tunes include some neat oddities, like a cover of Lesley Duncan’s “Love Song” (done slightly later by Elton John on Tumbleweed Connection) and the haunting “Lover to the Dawn,” which never made it onto a Bowie release, though it evolved into a song that did, “Cygnet Committee.” And you get to hear Bowie and Hutchinson unexpectedly segue into the chorus of “Hey Jude” near the end of “Janine.”

Another bootleg of material from the 1969 demo tape.

Aside from being the only document of that brief period in which Bowie and Hutchinson worked as a duo, I find this of even greater importance for capturing what might have been the true personal Bowie—or at least as personal a Bowie as he could summon given his chameleonic nature. Sincerity is not a quality we usually associate with him, but if there was any time where he meant what he sang, instead of writing as a character (or writing about other characters), this might have been it.

I asked Hutchinson if he’d agree with that assessment when I interviewed him about his memoir in 2014. “Yes, I would say, in those days he was just himself,” Hutch responds. “David Jones [Bowie’s birth name] and David Bowie were the same person. Whereas when Ziggy happened, it got a lot more complicated, and he was singing as somebody else. He was third person or removed, or whatever it is. He’d written songs for this alter ego or other person to sing. He could sing whatever he wanted them to, he could write whatever he wanted them to say, and maybe it wasn’t sincerity from him. But I don’t think he had a lot of that going anyway. I think it was all performance.”

“When you say you ‘don’t think he had a lot of that going,’ are you referring to the singer-songwriter approach?” I clarified.

“Yeah, I don’t think he had very much of that going at all. He was playing a part, and writing his stories, as the character that he’d created. So I’m agreeing with you, I suppose, that he was much more honest during those ‘Space Oddity’ days, if you like, the acoustic days. I think he was totally honest then, and it’s just that the way that he wrote and performed changed when he realized he could invent a persona. You know, David Bowie was just a stage name. But Ziggy Stardust was a character.”

Two of the performances from this tape, “Space Oddity” and “An Occasional Dream,” show up on the bonus disc of the 2009 CD reissue of the 1969 David Bowie album (titled Man of Words/Man of Music and then Space Oddity in the US). Some post-production cleanup/tampering seems to have gone on, however, especially on “Space Oddity,” which has a rudimentary blast-off effect missing on the bootlegged version. It would be great if the whole tape could be issued without any messing about, especially as the bootlegs—issued under various titles, such as the one pictured here, The Beckenham Oddity—have wobbly low fidelity that could presumably be much improved by accessing a better copy.

Read more about David Bowie’s music in early 1969 in John Hutchinson’s memoir, Bowie & Hutch. My full interview with Hutchinson appears in the winter 2014 (#6) issue of Flashback magazine.

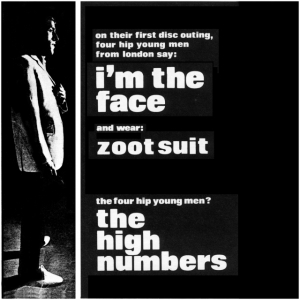

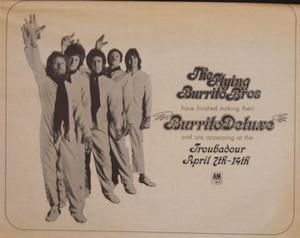

While it wasn’t too hard to narrow down the list of unreleased albums (or quasi-albums) from this era to my personal Top Ten, there were many others of interest, often with their own fascinating stories. Just some of the most notable ones that missed the cut would include Neil Young’s Homegrown (which might have made the list if we could actually hear the thing, though he recently intimated he’d like to finally put it out); Gene Clark’s Sings for You; Buffalo Springfield’s Stampede (which even got as far as getting a cover made); Joni Mitchell’s concert recordings from early 1969, which were given serious consideration for being selected as her second album; the Yardbirds’ March 1968 live recording in New York’s Anderson Theatre, which actually briefly came out in 1971 before Jimmy Page put a stop to it; Jackie DeShannon’s mid-1960s publisher demos; the numerous halted attempts at a Modern Lovers album in the early 1970s; Robin Gibb’s unreleased second solo LP, 1970’s Sing Slowly Sisters; the album cult acid folkie Dino Valenti cut with producer Jack Nitzsche…the list goes on, and maybe I’ll do a post detailing my picks from #11 to #20 in the future.

Could you write a book on these, and many others? Sure. And one day I’d like to do it, if any publishers are interested.

The protagonist in Lewis Shiner’s excellent book Glimpses is an obsessive rock fan who develops the ability to travel back in time through his dreams, where he tries with mixed success to help the Beatles, Brian Wilson, the Doors, and Jimi Hendrix complete their unfinished masterpieces.