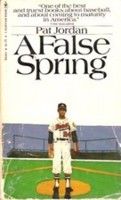

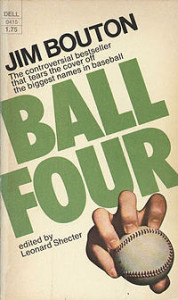

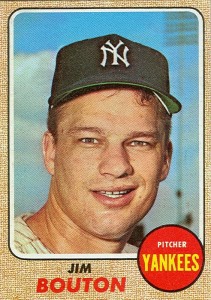

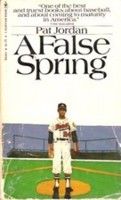

In a recent post, I hailed Jim Bouton’s Ball Four as “the Sgt. Pepper of baseball books.” I’ve found most other baseball memoirs (and there are many) disappointing, even some of the most highly praised ones. If pressed to pick #2 on the list, however, I’d go for Pat Jordan’s A False Spring, published in 1975. Bouton probably agreed, as he called it “the best sports book I’ve ever read” on a back cover blurb.

While Bouton’s diary shows some of the funniest (and, occasionally, some of the saddest) side of professional baseball, A False Spring is the largely grim underside. First off, you might be wondering who Pat Jordan is. He not only wasn’t a star (as Bouton was, if just for a couple years)—he never made the majors. But that actually makes him a more typical professional ballplayer than Bouton, and indeed the vast majority of baseball memoirists. Most players who make it to the minors never make it to the majors, and Jordan, despite getting a big bonus from the Milwaukee Braves in 1959, was a spectacular failure, only playing for three years and never rising above the class C league.

Most of his book, naturally, deals with his own struggles. There’s no better illustration of how talent doesn’t necessarily translate into success, in large part because, as Jordan admits with painful self-honesty, he lacked the maturity to effectively use his assets. He threw hard to pile up strikeouts at the expense of control, got into tiffs with managers and players, and quit the game altogether after a discouraging 1961 season in class D. In fact, he quit a few days before the season was over, putting the car in neutral so as not to wake the landlord when he and his new wife skipped out on their last month’s rent.

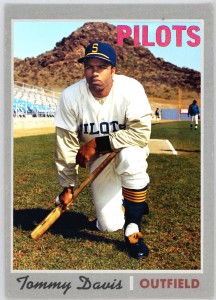

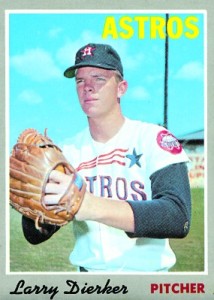

There’s lots more about his brief and checkered career in the book. Some overlooked aspects of his observations, however, are the idiosyncratic details he reveals about his teammates. Most of them, like Jordan, didn’t make the majors, but a good number of them did. Just like we’d never know some of the quirks of Don Mincher, Fred Talbot, Larry Dierker, Lou Piniella, Steve Hovley, Ray Oyler, and many others if not for Ball Four, so does A False Spring have quite a few odd tidbits about ballplayers who made the big time.

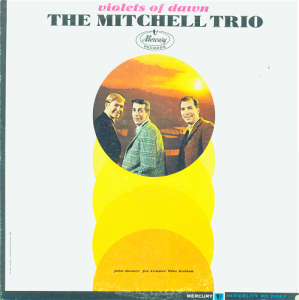

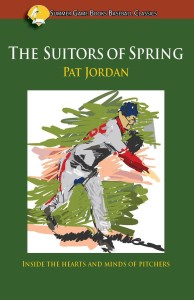

Pat Jordan’s first book, The Suitors of Spring, collected profiles of various major and minor league players and coaches, mostly pitchers.

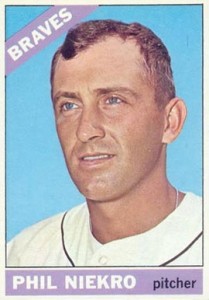

One of the most famous of Jordan’s teammates was Hall of Fame knuckleball pitcher Phil Niekro. For many years he was the ace of the Atlanta Braves’ staff, yet back in 1959, he was a relief pitcher for their class D team in McCook, Nebraska, after getting a mere $500 bonus. Jordan on Niekro:

At first he appeared only in the last innings of hopelessly lost games. He was ineffective because he could not throw his knuckleball over the plate and preferred, instead, to deal up one of his other pitches, all of which were deficient. He seemed deficient. He was tall and blond and affected a deferential slouch. I dismissed him as a timid man. Years later I would realize that what I’d mistaken for timidity was actually a simple nature. Phil Niekro was the least complex man I’d ever met. He devoted his life to mastering a pitch. He had been taught that pitch by his father when he was six years old and had still not mastered it when he reached McCook…

It was at McCook that Niekro first surrendered to the whims of this pitch and shortly thereafter, where his first success began. It is a surrender a more complex man could never make, but one that eventually brought Niekro a success none of his teammates at McCook would ever approach.

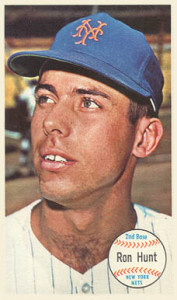

Jordan’s roommate in McCook was Ron Hunt, a scrappy second baseman who would play for a dozen years in the majors for several teams (though not the Braves). He’s most known for his willingness to take first base by getting hit by a pitch. He still holds the post-1900 major league single-season record in that category, taking one for the team 50 times in 1971. But at McCook Hunt was something of a milk’n’cookies guy, warning Jordan their landlady would throw him out if he came in drunk again (though Pat wasn’t drunk—more about that in a minute). Once Hunt introduced Jordan to his visiting mom and dad; a few weeks later, to Pat’s incomprhension, Ron introduced his roommate to an entirely different mom and dad (it turned out both his biological parents had remarried).

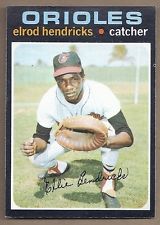

When the landlady thought Jordan was drunk, he’d actually gotten into a fight with teammate Elrod Hendricks. Hendricks eventually became catcher for the Baltimore Orioles, and was part of three consecutive pennant-winning teams in 1969-71 (and a World Series champion in 1970). Back in 1959, he was charged with warming up a nervous Jordan in his first minor-league start. Impatient with Elrod’s lazy throwbacks and dilly-dallying stabs at his throws, Pat ran to the dugout to get another catcher. The next morning he was reading a newspaper on a bench when, to his shock, a smiling Hendricks pummeled him to the ground. Hendricks thought Jordan had made him look bad to the manager.

After a decade or so in the majors, ironically, Ellie later became bullpen coach for the Orioles for 28 years. Wonder how he reacted when catchers warmed up Orioles pitchers with less than wholehearted enthusiasm, or when he might have had to do the job himself.

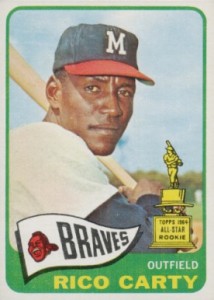

The next season, one of Jordan’s teammates was Rico Carty, later a Braves outfielder (and batting champion in 1970), but then a scuffling catcher in C ball. The Dominican was beginning the difficult process of adjusting to US life, and Jordan invited him out for a couple beers, after which Rico fell asleep right at the counter. This was Davenport, Iowa, not the Deep South, but as Jordan wrote:

The next time I entered that bar the bartender complained about my friend. I apologized for his behavior, assured him that it wouldn’t happen again, that my friend was just awfully tired…

“‘That’s not the point,’ he said. “My customers don’t want no buck nigger in here. Not even awake. You understand?’

“‘Sure,’ I said, a little stunned. Then he asked for proof that I was 21 years old, and when I couldn’t produce any he said he was sorry but that I’d have to leave.”

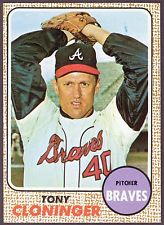

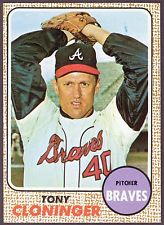

Also in the Braves’ farm system, Jordan came across Tony Cloninger. Cloninger would have a fairly lengthy career in the bigs, though only one real star season, 1965, when he won 24 games for the Braves. He was something of an overworker, and:

“When his fastball disappeared a few years later, he refused to accept the fact. He simply threw harder—that is, with greater effort. I remember seeing him pitch against the Montreal Expos in 1969. His career was all but over then. He lasted three innings. After he was relieved he walked to the right field bullpen and began firing fastballs to his bullpen catacher. He threw for five innings, as if punishing himself would redeem his career…

“I talked to him after the game. He told me he needed just a few more wins to achieve his hundredth major league victory. Nothing would stop him from reaching that goal, he said, not even the sore arm he now suffered. He just pitched with it, he said, and didn’t tell his manager, because if he did his manager might drop him from the starting rotation.”

Cloninger did get his 100th win late that year, by the way—and, the next season, he’d pitch for the Reds in the World Series, though not too well, starting and losing game three to Elrod Hendricks’s Baltimore Orioles.

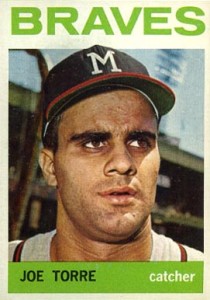

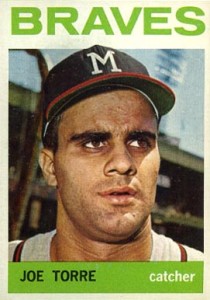

Jordan’s most fateful encounter with a teammate involved another future Hall of Famer. Eager to ingratiate himself with a manager, Pat offered to pitch batting practice one day in spring training in 1960 though his arm hurt. His catcher was Joe Torre, who angrily told him to “Put something on the damn ball!” When Joe turned his back Jordan threw the ball at his head, and they almost came to blows before the manager separated them. And that manager, Billy Smith, demoted Jordan to a lower classification after the incident—an incident that, in retrospect, the author felt saddled him with a reputation as a troublemaker.

There’s a happy ending of sorts, as dismal as Jordan’s career was. By the 1970s he was establishing himself as a top sportswriter, due in no small part to A False Spring. In 1996, he’d even write a story on that same Joe Torre, now manager of the New York Yankees, for The New York Times magazine; the pair had buried the hatchet, Joe having no problem with being interviewed by Jordan. And in 1997, at the age of 56, Pat pitched a scoreless inning for the Waterbury Spirit in the independent Northeast League, a comeback that formed the basis of a subsequent memoir, A Nice Tuesday.