There aren’t any blew-me-away music documentaries that came out in 2023, on the order of, say, Get Back. There are still quite a few worth viewing, often on subjects that would have been deemed impossibly uncommercial or impossible to film not too long ago. I did miss some I know have at least screened at festivals, and should they be easier to access in 2024, I’ll include them on a supplement to that list. There were still almost twenty I found worth writing about, and if they were heavy on well known figures, docs on the likes of Barbara Dane and Peter Case continue to emerge.

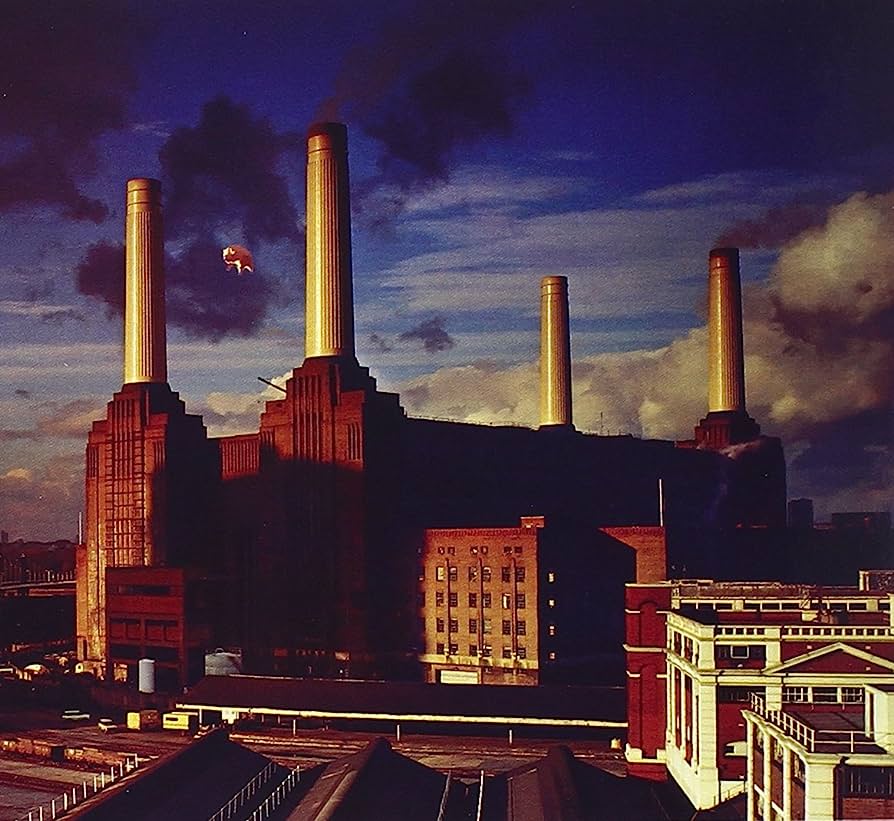

1. Have You Got It Yet? The Story of Syd Barrett and Pink Floyd. When this came out, I was concerned whether this was necessary since there was a pretty good documentary (primarily distributed through the DVD market and not widely screened in theaters) on Barrett almost twenty years ago, The Pink Floyd and Syd Barrett Story. I even wondered whether it was just a retitled or rejigged version of that documentary. It’s not; it’s an entirely different production. And though there’s naturally overlap in what’s covered (and some of the interview subjects), it’s worthwhile, primarily for the amazingly wide assortment of first-hand interviews with people who knew Barrett. That includes Roger Waters, David Gilmour, and Nick Mason of Pink Floyd, but also a host of others. Among them are early Floyd managers Peter Jenner and Andrew King, Barrett’s sister Rosemary, and several of Barrett’s girlfriends. Some who only pop up for brief comments are celebrities in their own right, like Pete Townshend and playwright Tom Stoppard.

Some of these interviews were obviously done quite some time ago, as several have since died, and co-director Storm Thorgerson died ten years ago. I could done without a few sequences in which actors with passing resemblances to Barrett seem to be silently reenacting surreal things Syd could have experienced or imagined. But mostly there are interesting memories and stories, and while the archival footage of Barrett with early Pink Floyd will be familiar to big fans, some of the vintage pictures won’t. It’s probably not giving anything away to readers of this blog that Barrett’s story was tragic in many ways, and his descent into mental difficulties and retreat from the music business isn’t glossed over. His substantial contributions to psychedelic rock are celebrated in detail, however, particularly his songwriting.

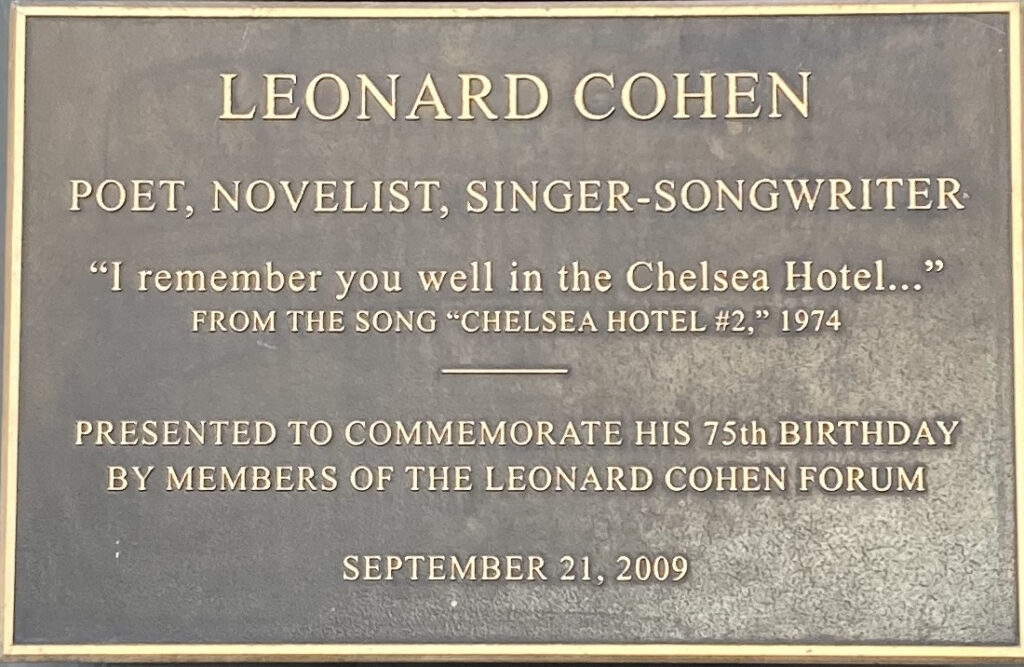

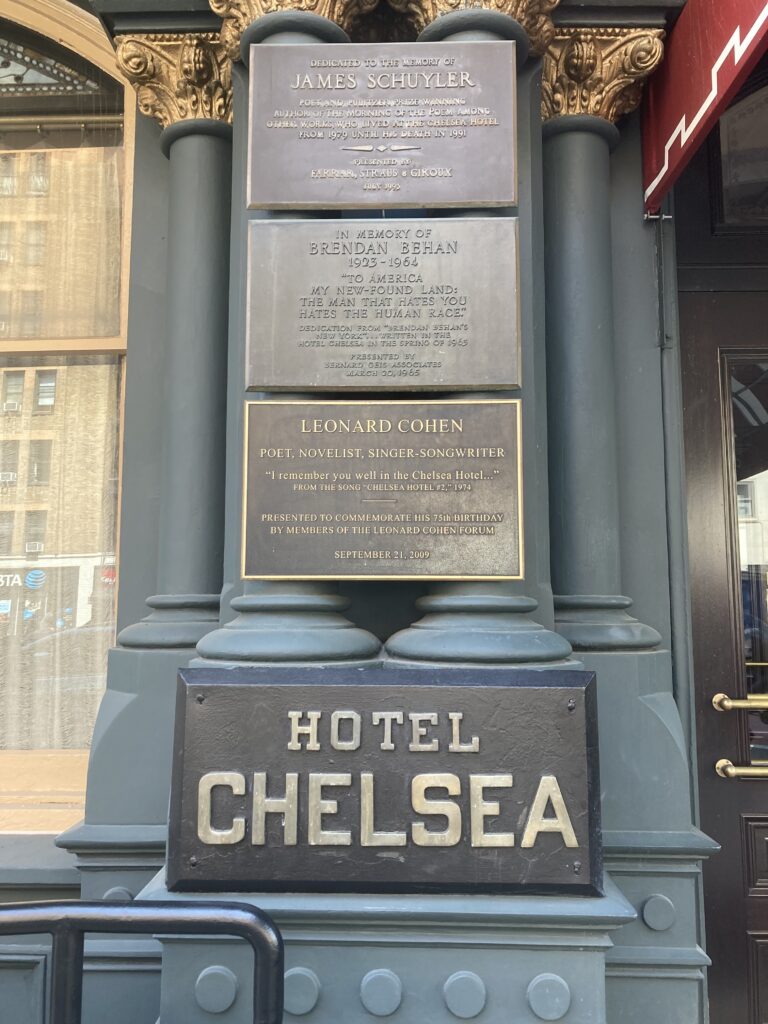

2. The Stones and Brian Jones. Known for quite a few movies with rather sensationalistic first-hand investigations by the filmmaker, Nick Broomfield has gotten more straightforward with his recent Leonard Cohen film (Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love) and this documentary about Brian Jones. There’s a lot more to say about Jones than can fit into about 95 minutes, and this doesn’t cover everything about his life and music; Paul Trynka’s biography Brian Jones: The Making of the Rolling Stones is the best source for that, and there are plenty of other details in other books. A longtime rock journalist I respect has also criticized this film for not using much for the original Rolling Stones’ compositions on the soundtrack; in a related weakness, not adequately covering the scope of Jones’s contributions to numerous songs by Mick Jagger and Keith Richards on unusual instruments; and the image quality of a few interview segments recorded on Zoom.

Fair enough points, especially if you’re looking for the ideal Jones documentary. But even as a longtime Stones/Jones fan, I liked what the movie did cover. A lot of the footage and photos are uncommon, and even if much of it can be uncovered in other various sources, it’s used adroitly to tie together strands of Brian’s story. A good number of soundbites from interviews with Jones’s girlfriends are used that aren’t exactly well-trodden info either, from Linda Lawrence to the less well known ones like Pat Andrews and Dawn Molloy. Bill Wyman has a lot of on-camera comments done recently specifically for this project, and some other lesser-heard-from figures were also interviewed, like film director Volker Schlöndorff, for whose film A Degree of Murder Jones composed the soundtrack. Sure it would have been nice if Jagger, Richards, early Stones manager Andrew Oldham, and some other key figures had been interviewed. But many, also including Marianne Faithfull and Jones’s father, are represented by relevant vintage interview fragments, often in voiceover rather than film (and it’s not always possible to tell what might have been taken from other sources rather than done for the documentary).

While Jones’s philandering and drug abuse are covered, there’s plenty of attention to his music, Wyman noting his slide guitar work and how Jones and Richards combined their riffs. Brian’s failed attempts at songwriting are discussed, and one particularly noteworthy segment includes a tape recording of a few lines from a tune he’s trying to work out. Unlike some other books and films, this doesn’t dwell on or sensationalize the controversial circumstances behind his 1969 death, though it is of course covered near the film’s conclusion. There are some minor inaccuracies in the chronological sequencing of the events that slightly diminish the film’s value, though they’re of the kind that don’t seem to bug many viewers except fanatics who trainspot these sort of details.

3. San Francisco Sounds: A Place in Time. Streaming on the MGM+ channel, this two-part, two-and-a-half-hour documentary focuses on the San Francisco psychedelic rock scene of the last half of the 1960s, though episode two goes a fair way into the 1970s. This is a decent overview that focuses on the most celebrated acts of the time: Jefferson Airplane, Big Brother & the Holding Company, the Grateful Dead, Santana, and Sly & the Family Stone, with some attention paid to Country Joe & the Fish, Moby Grape, Quicksilver Messenger Service, the Charlatans, Steve Miller, and the Tower of Power. Many of the artists dead and alive are represented by voiceover clips; the only talking heads seen on screen from recent interviews are a few non-musicians, including critic Ben Fong-Torres, radio DJ Dusty Street, light showman Bill Ham, and poster artist Victor Moscoso. There are quite a few (if very brief) archive film clips and photos, some quite rare or at least infrequently seen. Highlights among those are Big Brother in rehearsal, a snippet of Dan Hicks performing informally and solo, and famed radio DJ Tom Donahue.

What this documentary could have benefited from, at least for those who take this scene very seriously, is simply more time and depth. There were many interesting secondary musical acts in the scene who aren’t seen or even mentioned, some of whom were certainly filmed in decent quality, like It’s a Beautiful Day and Cold Blood. Some that barely or never recorded have interesting film clips too, like Ace of Cups. The Beau Brummels’ contribution as the first major ‘60s San Francisco rock group is, as usual in these productions, entirely overlooked, although you actually do hear an instrumental passage from one of their recordings in the background at one point. There’s arguably a little too much attention paid to non-musical aspects of the scene, like posters and light shows. And extending the coverage at the end to the Doobie Brothers and, more particularly, Journey (whose “Lights” plays over the end credits) is extending it too long.

My expectations might have been too high considering the co-director, Alison Ellwood, did such a good job (as the sole director) of Laurel Canyon, a survey of the 1960s/1970s rock scene in that area of L.A. that was one of the best recent music documentaries. A similar format is employed here, but the subject’s really worth four full hours.

4. Reinventing Elvis: The ’68 Comeback. Debuting as a stream on Paramount Plus, the documentary looks at Elvis Presley’s fabled 1968 comeback network television special. The story is told well in the book Return of the King: Elvis Presley’s Great Comeback, by Gillian G. Gaar, who is interviewed in this film. But this doc also benefits from interviews with some of the program’s dancers, audience members, a choreographer, and most importantly, director Steve Binder, whose extensive comments are the narrative thread of sorts. There are also, of course, numerous clips from the special itself, as well as outtakes not in the original broadcast. Running nearly two hours, it’s padded a bit by commentary on the general sociocultural context of 1968, Elvis’s pre-1968 career (especially his descent into poor movies), and, more problematically, testimonies from current artists as to Presley’s huge enduring influence (as if that’s ever been in doubt).

Binder’s detailed recollections of his interactions with Elvis, and the obstacles Colonel Tom Parker (largely unsuccessfully) threw in the way of doing the show Elvis and Binder’s way, are the key attractions, though the other interviewees have their share of worthwhile stories and insights. The tragic footnote was how Binder and Presley could not sustain their friendship after the special as the director was unable to contact Elvis, one interviewee speculating that had they remained close, Presley’s career would have turned out differently and better.

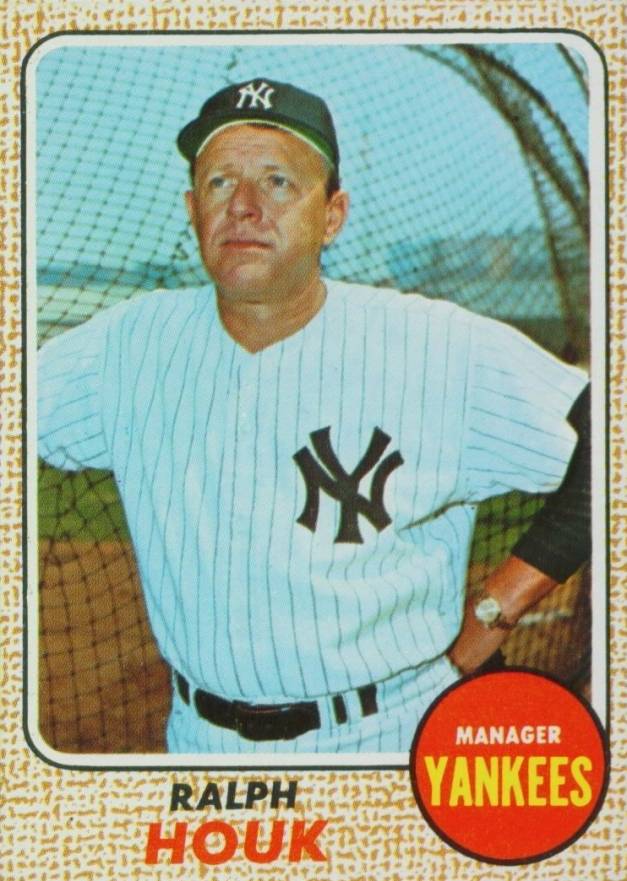

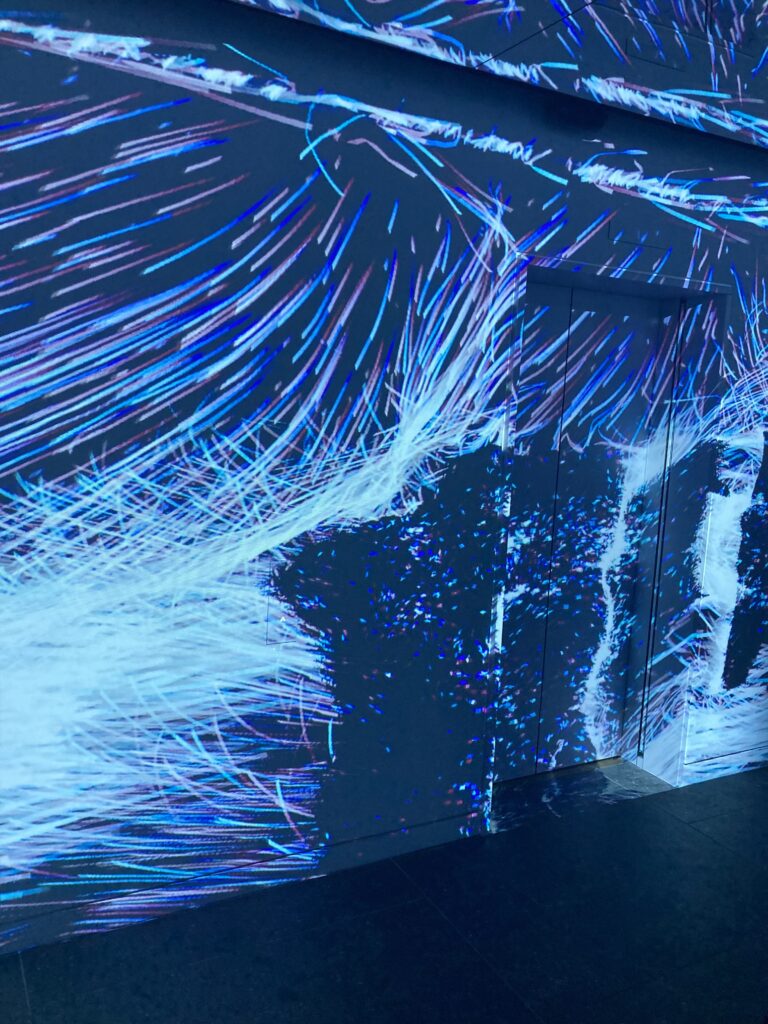

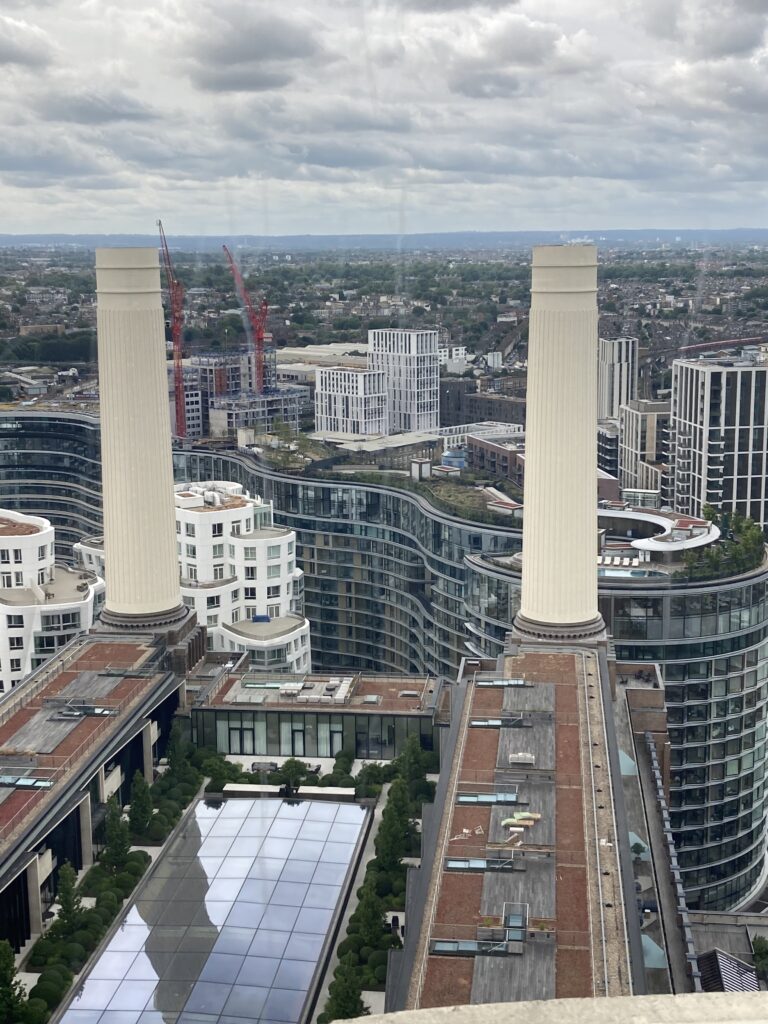

5. Squaring the Circle (The Story of Hipgnosis). Technically this first played a film festival in 2022, but didn’t start to circulate too widely until mid-2023, so I think it’s okay to put this in the regular 2023 listings. Hipgnosis was the design studio responsible for many classic rock album covers from the late 1960s through the late 1970s, formed by Storm Thorgerson and Aubrey Powell, though Peter Christopherson came in as a third partner in the 1970s. They’re most famous for Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon, but did several other Floyd covers as well as famous ones by Led Zeppelin, 10cc, Wings, and Peter Gabriel. They’re all discussed in depth in this documentary, directed by noted rock photographer Anton Corbijn. It’s straightforward in format, progressing chronologically with interviews with Powell, Paul McCartney, the surviving members of Pink Floyd, Robert Plant, Graham Gouldman, and Gabriel, as well as lesser known associated and friends. The only arty touch is filming the interviews in black and white, though the album covers and art are shown in full color.

As Thorgerson died about a decade ago, he’s only represented by some archival interviews. There’s vintage footage of Powell too, but he participated more than anyone in the interviews done for the film. Maybe some hardcore fans will lament the absence of coverage on some of their many relatively obscure album designs, whether for String Driven Thing (in which Helen Mirren can be seen) or Toe Fat. And while there are several books by now that tell much of the Hipgnosis story relayed here, it’s a well-paced overview of its highlights, as well as a reflection of a time when much time, art, effort, and money was put into elaborate sleeve designs, to the point of making special trips abroad in deserts and mountains to get the exact shots desired. Although appropriately brief, the time at which the team split in disputes over direction (some wanting to abandon sleeve design for videos) and finances is covered, Powell poignantly noting that he and Thorgerson—close friends as well as colleagues—didn’t speak for next twelve years.

6. Little Richard: I Am Everything. Little Richard makes a good subject for a documentary, and this is a good one, but with some minor flaws that keep it from being an excellent one. It covers much of his career with a wealth of vintage interview excerpts and performance snippets, along with comments by quite a few peers, associates, musicians he influenced, and (least essentially) academics. The singer is consistently charismatic as a vocalist, pianist, and storyteller, if one that constantly inflates his importance, if usually in a humorous way.

Although much attention’s given to his mid-’50s superstar peak, there’s also some adequate space for his detours into gospel music both in the late 1950s and later decades, as well as his reversions to rock in the early 1960s and later. Various notables, some obviously in interviews dating back many years, testify to Richard’s greatness, including Paul McCartney, Mick Jagger, Tom Jones, Nona Hendryx, and Nile Rodgers. Some of the less famed people who worked with him get some time too, like “Tutti Frutti” lyricist Dorothy LaBostrie and drummer Tony Newman of Sounds Incorporated, who backed Little Richard on UK shows in the 1960s.

As exciting as it is to watch him perform, the vintage musical clips, though numerous, are frustratingly short — very short, like just a few seconds. Some of the writers and scholars make obvious or redundant comments about his sexuality and the discrimination he suffered. Longer music excerpts would have enhanced the impact considerably, and if those behind the film felt that would have made it too long, that’s underestimating the appetite of the audience. I believe most of them, myself included, would have welcomed extension of the film by about twenty minutes to reach the two-hour mark, if that would fit in more such material. Performance visuals aren’t the only things shortchanged — Jimi Hendrix’s pre-fame mid-’60s stint in Richard’s band is only mentioned, and the sequence of what happened when, as it is in many documentaries, sometimes gets out of order, though few except serious fans will catch these.

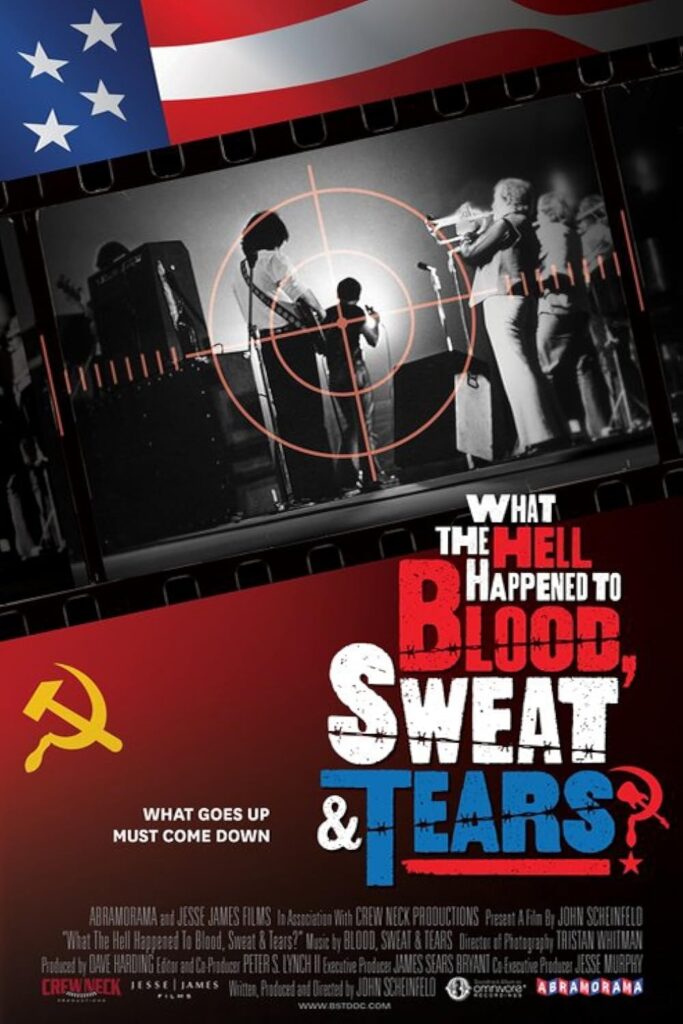

7. What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat & Tears? Blood, Sweat & Tears are never going to be considered among the hipper acts of the late 1960s and early 1970s. But for a couple years or so, they were one of the most popular rock bands in the US. While there’s much about their history in this documentary, it centers on their 1970 tour of Eastern Europe, which included shows in Yugoslavia, Romania, and Poland. (For what it’s worth, contrary to a remark in the film, this wasn’t the first time an American rock band played behind the Iron Curtain; the Beach Boys played a few shows in Czechoslovakia in June 1969.) A different documentary of that tour was made at the time, and while much of it is lost, the recent discovery of some of the footage means that a fair amount of it is used in this movie. The director of the tour documentary, Donn Cambern, is interviewed in this new overview, as are several key members of BST, including singer David Clayton-Thomas, Steve Katz, and Bobby Colomby, and Jim Fielder. So are record executive Clive Davis and rock journalist David Felton, who wrote critically about the band at the time.

It wasn’t known by many at the time that BST agreed to the State Department-sponsored tour to keep Canadian native David Clayton-Thomas from being deported. The band had mixed feelings about doing it for other reasons, including embarking on what could have been considered cooperation with the government at a time when there was a lot of opposition to its policies (especially US involvement in the Vietnam War) among their audience. Footage from the tour itself reveals wildly varying reception from the Eastern European audiences, from enthusiastic near-rioting to, if at only one concert discussed, hostile indifference. Upon their return, some of the musicians noted their discomfort at visiting countries where some personal liberties were curtailed and suppressed. This in turn generated some hostility from the counterculture and rock press who viewed them as tools of the US authorities, their hip quotient further diminished by taking gigs in Las Vegas. This is cited by some of those interviewed as a principal factor, perhaps the principal factor, in the band’s diminishing popularity and descent from superstardom.

Although it’s interjected irregularly, the film does also cover some of the group’s general history. It takes a while to get to it, but their origins as an Al Kooper-led group with hipper musical credentials on their debut album is detailed (though Kooper isn’t interviewed), as is his departure and the recruitment of Clayton-Thomas, the band feeling they needed a better lead singer. So is their appearance at Woodstock, including some concert footage, though not much was filmed of them at that festival, their manager at the time getting blamed for asking for money. A subsequent manager was recommended to them despite his being in jail at the time; he was hired, and was the manager during their Eastern European tour. There’s also discussion of their integration of horns into rock arrangements and its influence at the time, though even at that time, it wasn’t as big a hit with critics as with the public.

While very interesting, if a little erratically constructed, the film doesn’t entirely satisfactorily deal with the effect of the tour and the group’s subsequent struggles. The tour might have cost them some credibility with critics (like Felton, who wrote about them in Rolling Stone at the time) and some audiences, but there certainly wasn’t an immediate effect on their popularity. Their third album spent a couple weeks at number one in August 1970, after the tour was finished. The possibility that Clayton-Thomas’s departure (which isn’t mentioned) in the early 1970s, and a drop in quality in their recordings, might have played a significant role are not considered as factors.

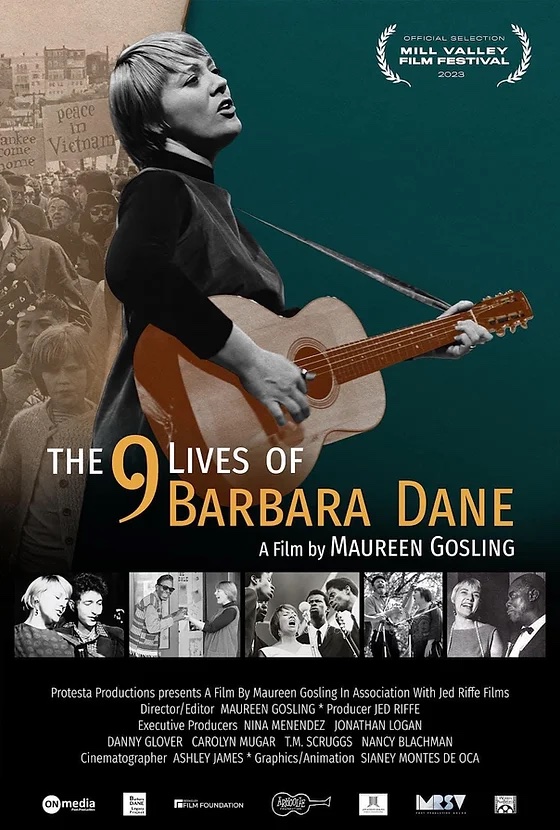

8. The 9 Lives of Barbara Dane. Dane has had an interesting life, to say the least, both as a musician and activist. Although most identified with the folk revival, from the 1950s through the 1970s she also recorded some jazz and records that even bordered on pop-rock, as well as doing a mid-’60s album with the Chambers Brothers. Her left-wing activism included membership in the Community Party in her younger years, involvement in the Civil Rights Movement, obstacles her politics threw in her career path during the McCarthy era, and travel to Cuba in the mid-’60s at a time when few American artists went there, which led to appearances throughout the world, including in East Germany. She was married for a long time to Sing Out magazine editor Irwin Silber, and helped run a record label, Paredon, that put out many world music and politically minded discs. She turned down a management offer from Albert Grossman, before, she says in the documentary, he handled more famous clients like Peter, Paul & Mary and Bob Dylan.

All of this is covered in this film, though it can’t go into all this and more as much her recent memoir The Bell Still Rings: My Life of Defiance and Song does. This does offer numerous recent interviews with Dane, still alive as of this writing in her mid-nineties, as well as children and fellow musicians and activists, Jane Fonda and Bonnie Raitt being the most famous. Considering she never became a star or even sold too many records within the folk or jazz communities, there’s a surprising wealth of archive footage, including network TV appearances on the Alfred Hitchcock Hour and Playboy After Dark. Most amazingly, there’s also footage of her travels and musical appearances in Cuba in the 1960s, and many interesting photos help round out the story. It doesn’t always follow a straight chronological order, though she was doing so many things nearly at once it would be hard to film this in timeline fashion. Her post-1970s years, during which she was largely inactive in music, don’t get much time, though there are quite a few clips of her when she began performing more in her eighties. The narrative intersperses those with her basic history from the 1940s through the 1970s, which actually works better than lumping that in at the end.

9. Psychedelicized: The Electric Circus Story. From 1967 to 1971, the Electric Circus was one of New York’s leading rock clubs, located in the East Village on St. Marks Place. While this 90-minute documentary isn’t extraordinary from a filmmaking point of view, it’s very competent, mixing archive photos and footage with interviews with some of the venue’s main figures, concertgoers, and a couple performers from major bands who played there. Among those interviewed are founders Jerry Brandt and Stan Freeman; Lester Chambers of the Chambers Brothers; and Sly & the Family Stone drummer Greg Errico. There isn’t much film of actual musical performances at the club, those being limited to silent clips of Sly & the Family Stone and the Voices of East Harlem. But there are a good number of bits of the many non-musical circus-like acts who also performed there; shots of the audience grooving; and news clips of the time covering the Electric Circus and interviewing audience members.

Although overshadowed by the Fillmore East, and even some other venues like Steve Paul’s Scene, in coverage of New York’s psychedelic-era rock, this film makes the case (not overtly) that it should get more attention. More than other venues in New York and elsewhere, it was a multimedia experience, not just due to the light shows, but the aforementioned circus-like performers, like mime artist Michael Grando, one of those interviewed for the documentary. The space’s prior history as the Dom (noted for regular Velvet Underground performances in spring 1966) and the Balloon Farm is acknowledged. So is the tragic bombing, for still unknown motivations, in 1970 that injured seventeen and likely increased the damper on things that led to the club’s closure in 1971. So is the bust of Brandt for having a joint in his luggage when entering Canada, which led to him being ousted from the club’s operations, and a split between him and Freeman that was never repaired. I streamed this from a festival and it’s possible it might not screen widely or make it to home video, but it’s worth watching for fans of ‘60s rock.

10. Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over. This is yet more average than the average music documentary, with plenty of testimonials to Warwick’s talents and character; plenty of snippets from archive clips, most very short, but including many of her numerous hits; and lots of recent interview comments from Dionne herself. As evidence of how widely respected she is among her peers, the interviewees—some of whom must have been filmed a few years before this went into wide release, and not everyone is still alive—include Burt Bacharach, Smokey Robinson, Chuck Jackson, Gladys Knight, Berry Gordy, Elton John, Clive Davis, Barry Gibb, Cissy Houston, Stevie Wonder, and even Bill Clinton. There’s not a great deal that serious fans won’t know, but her style and collaborations with producer/songwriters Bacharach and Hal David are discussed, as is her wide appeal to both black and white soul and pop fans. There’s attention to her activism during the Civil Rights era (which included a risky attempt to change lyrics in “What’d I Say” to refer to integration) and, more extensively, her involvement in AIDS-related causes. Although there aren’t many non-hit songs among the vintage clips, one of the most unusual has her singing in Italian, and there are so many clips sourced that few if any viewers will have seen all of the originals.

This is also like many documentaries in how it loses steam when it passes her musical prime. The last third or so is more about her considerable post-1970s humanitarian activities than her music, which got a lot duller after her association with Bacharach-David ended. How that (and indeed the partnership between Bacharach and David) ended isn’t discussed, and while her controversial involvement with the Psychic Friends Network and bankruptcy are, they’re not examined in much depth. Her sister Dee Dee, who made a lot of records, some very good, without getting big hits isn’t mentioned, although she’s seen in a news clipping. A documentary can’t cover everything, or everything in depth, but some fans, and I’m one, would like to know more. And not necessarily about the negatives—there isn’t anything substantial about her relationship with the Scepter/Wand label, which put out most of her big hits, or Florence Greenberg, who ran the label. Or how she felt about Cilla Black quickly covering and getting a big hit with “Anyone Who Had a Heart,” though that’s been gone over elsewhere. For many subjects, there are supplementary books to fill in a lot of gaps that documentaries can’t address. There hasn’t been a good one by or about Dionne Warwick, and time’s running out to get first-hand comments from those who were there for such a volume.

11. Joan Baez, I Am a Noise. With a lot of participation from Baez in recent interviews and concert footage from shortly before her retirement from touring, this nearly two-hour film has a greater autobiographical feel than many documentaries. That helps lead to pluses and minuses, the pluses being a good deal of archive footage going back to childhood home movies and 1958 live performance (with sound) at Cambridge’s Club 47. There are also lots of photos, rare documents, and letters (principally by Joan herself) going back to her pre-professional years. Other figures represented by interviews both vintage and done for this project include ex-husband and noted antiwar activist David Harris, her son Gabriel, and other family members. Important junctures in her career that are covered include early appearances at the Newport Folk Festival; her musical and professional relationship with Bob Dylan; her mid-‘70s resurgence with the Diamonds & Rust album and touring with the Rolling Thunder Revue (though, oddly, her one big hit single, a cover of the Band’s “The Night They Rode Old Dixie Down,” is not mentioned); and social activism that at times landed her in jail. Some scenes briefly show a huge archive of Baez material, some of which presumably was sourced for this movie.

Baez also spends a good deal of time ruminating over her difficulties with her family, including intimations of abuse on the part of her father, though the particulars aren’t too thoroughly detailed. She also gives a lot of space to discussion of her psychological problems, often referred to in letters that are blown up on the screen, and sometimes illustrated with animation. There are often transitions between her history and recent scenes of her traveling and on tour, and as often occurs, the recent sections are both less interesting and derail some of the momentum of the pre-1980 stories. Much that could have been covered of her purely musical evolution isn’t here, whether how she got acquainted with the traditional folk music that comprised the bulk of her early repertoire; her at times awkward attempts to move from solo folk to fuller arrangements and rock, which included an attempt at an unreleased mid-‘60s rock album produced by her brother-in-law, Richard Fariña; and her longtime relationships with Vanguard Records and manager Manny Greenhill. One of the recordings heard is a presumably teenaged Baez singing “Why Do Fools in Love,” and it might have been interesting to hear her views on rock, why she opted for folk, and how she felt about how the music scene changed as folk and rock mixed.

Some of this is covered in other books (though not very satisfactorily in Baez’s autobiographies) and liner notes, as well as the 2009 American Masters documentary How Sweet the Sound. I had the feeling, however, that Baez was undervaluing her musical career, or at least underestimating viewers’ interest in it. Maybe that says more about what I want in a documentary than what Baez wanted to express in this one. Still, there’s a gap in Baez’s legacy without a memoir, documentary, or biography that gives more space to her music and influence. Doing such a project wouldn’t prevent her from writing books and being in projects outside of music; Judy Collins, for instance, has also written multiple books, but did focus on her musical prime in Sweet Judy Blue Eyes. Baez did have the sense of humor to mock the cover of her Blowin’ Away album as one of the worst of anyone’s, attributing some of the impetus behind deciding upon the strange attire in which she’s dressed to her use of Quaaludes at the time.

Baez’s sometimes strained relationship with her younger sister Mimi Fariña gets a lot of screen time, and something should be noted about its portrayal. It’s presented as a loving but competitive and sometimes fraught one. Viewers might get the impression Mimi— who played guitar and sang in a duo with first husband Richard Fariña on pretty impressive mid-‘60s albums, as well as doing some later far less noteworthy recordings—wanted to have Joan’s stature as a musician, but lacked the talent and spent her adulthood in her sister’s shadow. Musically that might be true to some extent, but it’s not mentioned that Mimi Fariña founded the esteemed (and still operating) organization Bread and Roses. It presents concerts for parts of the population that might have a hard time going to such events otherwise, such as prisoners and people of all ages struggling with disadvantages. That’s as much of a legacy to society as what Joan did in her own highly valuable work for social causes.

12. Peter Case: A Million Miles Away. As a disclaimer, I’ve known singer-songwriter Peter Case for nearly twenty years, and also been friends with his wife, journalist/author Denise Sullivan (who’s interviewed in this film), for longer than that. I’ve known a few other people interviewed in this documentary too. But I do think this film will be of interest to anyone interested in the more adventurous side of the mainstream music business in the past half century or so, and the more mainstream side of the independent/underground world. Case has sort of straddled those worlds, first as part of new wave groups the Nerves and the Plimsouls in the 1970s and 1980s, and since then as a solo act who has blended and flitted between folk and rock. He’s never made it “big,” in part because, as he acknowledges here, he hasn’t been the greatest at working personal relationships with people who work at labels and publicizing musicians.

This doc has archive clips going back to his days as a street singer in San Francisco in the 1970s, interspersed with excerpts from recent performances. Case recounts his breaks and setbacks with wry humor, as laid out in one of his first interview remarks, when he remembers David Geffen asking him “what happened?” after Peter’s career didn’t take off. “I go, ‘You’re David Geffen,’” Case replied. “You tell me what happened.” He also recounts, with no shame, how he got “lower education” in the San Francisco streets while his peers were getting higher education in school, and how he was dropped from a major label because he was too inexpensive (sic) to promote.

Refreshingly, there aren’t interviews with more famous musicians and writers to validate how important he is; instead, we hear from peers from the world of performers that gained critical respect without stardom, like members of the Balancing Act and Lone Justice, Chuck Prophet, and Case’s ex-wife, fellow singer Victoria Williams. Prophet chips in with a witticism of his own when noting how, along the lines of the oft-quoted line that all of the few people who bought Velvet Underground albums formed bands, all of the few people who bought Case records were also inspired to leave their bands and go solo. Case seems happy enough in his cult-ish niche, though the major scare he endured in his fifties when he needed to have a bypass operation without health insurance is also part of the story, as is the rally of fellow musicians and fans to help cover his expenses.

13. Little Richard, American Masters (PBS). This is an entirely different documentary than the theatrically screened film Little Richard: I Am Everything, which was released shortly before this episode in the American Masters series was broadcast on PBS. Inevitably it covers some of the same ground, but it’s certainly less lively. Maybe that’s to be expected from an installment in a long-running series known for a straightforward style, but it’s less interesting than I Am Everything, even though it’s almost as long. It too mixes vintage interview and performance clips with comments from associates, British Invasion stars Ringo Starr and Keith Richards (both of whom played on bills with Little Richard in their bands’ early days), and writers. Specialty Records chief Art Rupe is represented by audio, at one point noting the company did everything to get the star to record rock’n’roll again after he went gospel, even withholding royalties as part of that effort. Unlike I Am Everything, Pat Boone is among the interviewees, and while his take that he helped break Little Richard to a wider (and whiter) audience is dubious, at least he’s given the chance to offer his two cents.

As in I Am Everything, the performance clips are too brief. As great as Little Richard was, both documentaries make too much of him as an almost singularly titanic figure, boosted of course by many comments from Richard himself. It’s not an issue worth arguing too fiercely about since his importance is undisputed, but it should be noted, and is not in this film, that he wasn’t the only African-American rock’n’roll pioneer crossing over to white audiences in a big way starting in the mid-1950s; Chuck Berry and Fats Domino were just the biggest of those stars. Finer details about how his 1960s and early 1970s rock’n’roll comeback records on various labels didn’t catch on in a big way aren’t discussed, and Jimi Hendrix’s brief but colorful pre-stardom mid-‘60s stint in Richard’s band isn’t mentioned. If such info’s felt too mundane by documentary filmmakers, it’s out there in various books, though there hasn’t been a great one on the singer. If not as good as I Am Everything, this American Masters installment still adds material to documentary coverage of this icon, though it’s more supplementary than as interesting a film in its own right.

14. Max Roach, American Masters (PBS). The American Masters series broadcast episodes on three major African-American musicians in 2023, a welcome contribution to the PBS schedule. This nearly 90-minute overview of jazz drummer Max Roach was the best of the three as far as how well made a film it was, and would rank higher on this list if I was more of a jazz fan and thus more interested in the subject matter. It offered a lot of interest for me nonetheless, covering his journey from bebop (especially in the lineup he led with Clifford Brown) to Civil Rights-oriented music with then-wife Abbey Lincoln and later projects that focused on solo drumming and percussion ensembles.

With a guy whose career spanned more than half a century and had a discography of well over fifty albums (not counting the many he played on for other bandleaders), it’s not possible to do such a program without leaving a lot out. That might annoy some serious jazz aficionados, but what’s covered is covered well, with some excellent performance footage of his bebop days, excerpts from his Freedom Now Suite (his most well known and arguably most important work, with vocals by Lincoln), his M’Boom percussion orchestra, and even a clip of him and Lincoln performing in Iran in the late 1960s. There are also interviews with several musicians who worked with Roach, and several of his children.

15. Roberta Flack, American Masters (PBS). Like all American Masters episodes on musicians, this mixes archival clips with interviews, some vintage, some recent. It’s artier in its format than most installments in the series, though, using voiceovers instead of talking heads for the interviews. These include not just a lot of comments from Flack, but also from associates like producer Joel Dorn, ex-husband and jazz musician Steve Novosel, some musicians who played with her, and more contemporary journalists and musicians. There’s a lot of detail on her big hits “First Time Ever I Saw Your Face,” “Killing Me Softly with His Song,” and (with Donny Hathaway) “Where Is the Love.” These include comments by Lori Lieberman, who did the original version of “Killing Me Softly,” and Clint Eastwood, whose use of “First Time” in Play Misty for Me revived interest in Flack’s cover and propelled it to #1 three years after its release on her debut LP. Attention’s also paid to the origination of her pop-jazz-soul in front of club audiences in Washington, DC; the prejudice she endured as a result of her interracial marriage; and a few lesser known songs, including a few of her more socially conscious ones from her early recordings.

It might not have been the intention of those making the film, but this wouldn’t make a big case for her being a major artist, certainly not to those not very familiar with her work. As noted, not too many of her songs are discussed aside from the three big hits, and there’s not much of a sense of how many records she did and what others might have been significant. Maybe room, for instance, could have been made at least for the Janis Ian-penned “Jesse,” her Top Thirty (just) 1973 follow-up to “Killing Me Softly.” The documentary also adheres to the cliché of getting much less interesting after an hour or so, with a lot of space for her association with Peabo Bryson and some general comments from more contemporary artists.

16. Garland Jeffreys: The King of In Between. A singer-songwriter who never broke through to large-scale commercial success despite a lot of critical acclaim, Jeffreys was also hard to classify owing to his mix of rock, soul, reggae, and more. Hence the “in between” of the title, also referring to his mixed-race background. This 70-minute documentary is as modest in scale as his impact on the music scene was, even at his 1970s height, and is standard in format, blending interviews and archive clips. Those interviewed include Jeffreys himself, his wife and daughter, some brief bits of praise from contemporaries like Bruce Springsteen, and colleagues like guitarist Alan Freeman and producer Michael Cuscuna.

Such was the rather subtle and sometimes low-key nature of his work that it’s hard to imagine newcomers being blown away from exposure to it, but the movie, like his music, is reasonably interesting. His volatile relationship with the record industry, which saw him bounce between several labels, had something to do with his failure to make more commercial headway, though this could be said of many artists. There are a good number of brief clips of him in action from the late 1970s and early 1980s, and the strange juncture in which he blackened his face with minstrel-like getup for performance is covered. So is his sole hit of sorts, “Matador” (though then only in a few European countries), whose release as a single was suggested by Gene Simmons. His albums grew sporadic after the early 1980s, and his last few decades are covered lightly, ending with conveying the sentiment that he came to appreciate the devoted following he had rather than ruminate over his lack of greater recognition.

17. The War on Disco (PBS). A polarizing musical and cultural force, disco was both phenomenally popular and widely hated, culminating in a Disco Demolition Night at Comiskey’s Chicago Park in which records were burned and a major league baseball game forfeited. That event is also the key culmination of this hour-long episode of PBS’s American Experience series, which looks at how disco both rose in the 1970s and generated fierce antipathy among many music listeners. This doesn’t have much examination of the music itself and how it evolved out of soul and was produced in the studio, though some key records like “Soul Makossa” and “I Will Survive” are highlighted. The dominant viewpoint in this doc, expressed by some cultural commentators and a few disco performers, is that disco largely grew out of the black and gay communities, and the backlash was from white males who both felt threatened by its cultural expression and disliked the perceived elitism of clubs like Studio 54. Some other viewpoints are expressed, some feeling that the Chicago DJ (Steve Dahl) who spearheaded the Comiskey Park event wasn’t racist, but bitter over getting fired when his station changed format from rock to disco (though he quickly landed a job at another station). The archive footage and photos feature clips of dancers and clubs rather than performers, and naturally the Comiskey Park event where the record blowup grew into beer-fueled chaos.

The following films came out in 2022, but I didn’t see them until 2023:

1. In the Court of the Crimson King: King Crimson at 50. This first screened at very select outlets in 2022, and didn’t get its first San Francisco screening—or, apparently, much screening in commercial theaters—until November 2023. So it could have gone into the main section of this list, though it wouldn’t have been too highly ranked. This alternates between interviews with/footage of King Crimson in 2019 and some attention paid to their lengthy history, including interviews with some of their numerous past members and some (and certainly not a ton) of archive clips. If anything, this favors the 2019/recent footage, almost to the extent that it’s as much a documentary of that iteration of the band as it is of King Crimson as a whole. This is a fairly common approach in music documentaries, and not one I usually endorse, especially for a band with a career as lengthy and complex as King Crimson’s. Maybe the filmmaker wouldn’t have had as much access—including a lot of recent interviews with King Crimson mainstay Robert Fripp—as he did without giving the then-current (and still fairly recent) lineup as much weight.

There’s some history here, but in bits that are more tantalizing than satisfying. From the band’s first and still most famous (if short-lived) iteration, Michael Giles, Ian McDonald, and lyricist Pete Sinfield are all interviewed, but without much insight into how the group came up with their highly distinctive brand of progressive rock, or the musical (rather than personal) specifics as to why it quickly collapsed. There are also interviews with important subsequent members like Bill Bruford, Jamie Muir, Mel Collins (who rejoined in the 2010s), and Adrian Belew, but no substantial discussion of how and why the group’s style changed so often (and, sometimes, radically) over the decades. Clips from as early as 1969 (though in crude black and white for that year) and the ‘70s and ‘80s are cool, but very brief. A brief homage in the credits to all the members who aren’t heard from (and, in some cases, not mentioned) fills up an entire screen, including such key names as Greg Lake, David Cross, Boz Burrell, and John Wetton. It could be argued that the main audiences for the film are King Crimson fans who know a lot of that stuff anyway, but then again some of that audience wants to learn more of that stuff, or at least hear and see some surprising and fresh content.

If you want to concentrate on what’s here rather than what’s missing, Robert Fripp lives up to his image as a curmudgeon with stuffy and reasonably amusing comments. These both attest to his musical perfectionism and make clear his disdain for being analyzed, as well as the time such interviews take away from practicing and concentrating on his work. Various fanatical fans testify to the strength of Crimson’s cult—a predominantly male one, it’s fair to say, especially judging from the audience shots from various 2019 concerts. One subplot of the recent coverage is of special note for being poignant without getting maudlin. Multi-instrumentalist Bill Rieflin was part of the group for most of the 2010s though he’d been diagnosed with a terminal illness, spending his final years playing with the band in an effort to do as much as he could before dying in 2020.

2. The Day the Music Died: The Story of Don McLean’s American Pie (Paramount Plus). At around the fiftieth anniversary of this massively popular song, this hour and a half documentary looks at its genesis and realization. It’s stretched out a bit more than it should be to get to its length, but on the whole it’s pretty interesting, even if you’re not a huge fan of the song or McLean. Crucially, it’s not just about the song, also devoting some time to McLean’s early years and recording career. It also goes over the circumstances behind the plane crash that took Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper’s lives, and inspired, if that’s right word, the composition. McLean himself is interviewed a lot, as are some other relevant figures, like producer Ed Freeman, session musician Rob Stoner, and a sister of Valens. Some short segments with contemporary artists performing and discussing “American Pie” aren’t necessary, but they don’t take a lot of screen time.

There are some sides to the story that are interesting and not so well known, like the influence of Tim Hardin’s “Bird on a Wire” on McLean; the crucial role session pianist Paul Griffin played in the hit recording; and a 1971 radio broadcast in which Pete Seeger, with whom McLean had played, hails “American Pie.” McLean also goes through the lyrics and construction of the song in detail (verse by verse at one point), and there’s recent footage from the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake, Iowa, where Holly, Valens, and the Big Bopper played their last show before their deaths.

3. Nightclubbing: The Birth of Punk Rock in NYC (MVD). This focuses on just two clubs, Max’s Kansas City and CBGB, mostly during the 1970s, when they were both vital to the birth of punk and new wave. There’s considerably more coverage of Max’s than CBGB, although the latter isn’t neglected. It’s a rather modest documentary, without much in the way of star power or amazing vintage footage. But a good number of people from the scene are featured in the interviews, some of them famous or pretty well known, like Alice Cooper, Lenny Kaye, Syl Sylvain of the New York Dolls, and Billy Idol, along with somewhat lesser knowns like Jayne County, Elliott Murphy, and (briefly) Suicide’s Alan Vega. And there are quite a few contributions with more cult or behind-the-scenes figures like photographer Bob Gruen, Max’s booker Peter Crowley, New York Dolls manager Marty Thau, and members of Ruby and the Rednecks and the Testors.

While you can find out plenty more about Max’s, CBGB, and New York punk/new wave from many other books and documentaries, this still has a lot of decent stories and perspectives that will interest aficionados. Some of them verge on more details that you might want to know (particularly the anatomical ones of County), but insightful points are made about the peculiar attractions and repulsions of each space; how some bands were more interested in getting record deals than making artistic or political statements; and Max’s struggles to simply survive with changes in ownership and financial/legal troubles, which according to some accounts here included counterfeiting money. There isn’t as much performance footage with full audiovideo as there should be, much of the non-talking head visuals filled in by silent clip excerpts and photos. There are, however, a few actual vintage live clips of Murphy, Ruby and the Rednecks, Sid Vicious, and the Testors to evoke the atmosphere of seeing the acts on small stages in the era.