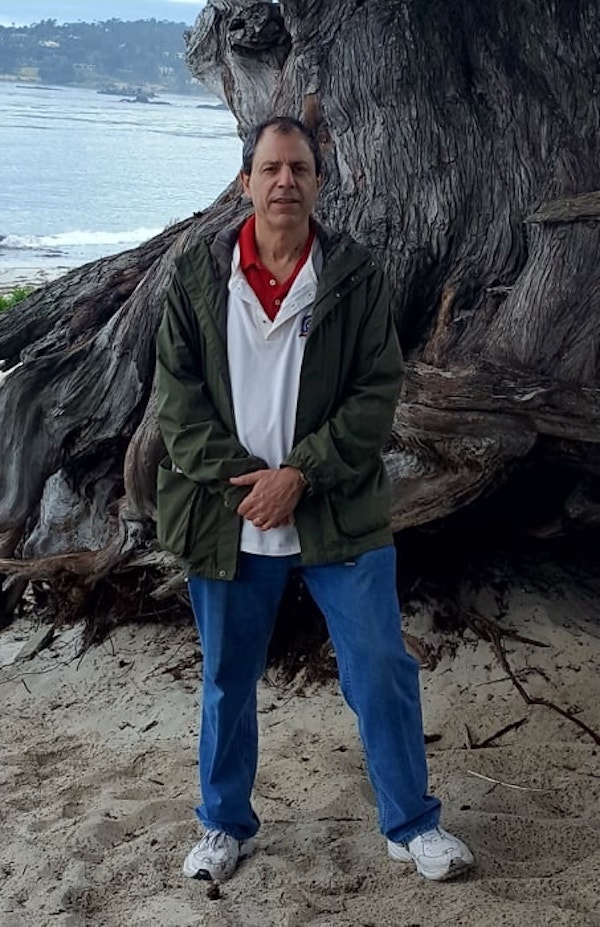

My oldest brother, Glenn Unterberger, died unexpectedly in his home just outside Philadelphia on October 14, aged 65. He had many interests besides music, and there were many worthy aspects of his life besides his passions for music and sports. But as those passions were repeatedly cited by relatives and friends at his funeral this week, and as I’m known mostly as a music writer, this tribute will focus on how his musical loves impacted my own life.

Glenn was nine years older than I am, and our careers and lives took very different paths. Moving to the San Francisco Bay Area (where I’ve mostly remained since) right after college, I became a writer and, in recent years, a rock music history teacher and lecturer as well. He took the more secure path of practicing law, first with the Environmental Protection Agency in Washington, DC, and then for a law firm in his native Philadelphia for the last nearly thirty years of his life.

Yet his influence on the way my life turned out was considerable, if somewhat subtle. In my work as a writer and adult education teacher, people often ask me, how do you know so much about music that was made when you were too young to hear it? Well, mostly I learned it on my own, the hard way, listening to whatever I could on oldies and classic rock stations while growing up; reading whatever rock history books I could, though there weren’t many in the 1970s; and buying whatever I could that I got curious about, often on the basis of just a few songs I’d managed to hear that got on the airwaves.

There was no internet to instantly call up a library of millions of vintage songs; no college/public radio stations I could get with specialty shows playing non-hits; no groaning shelves of biographies, histories, and memoirs of pre-1970 rock greats. I didn’t have to walk through three feet of snow to a one-room schoolhouse at 4am, but you get the idea.

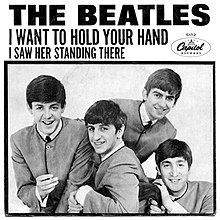

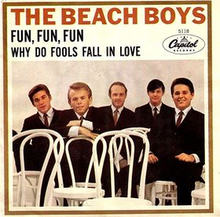

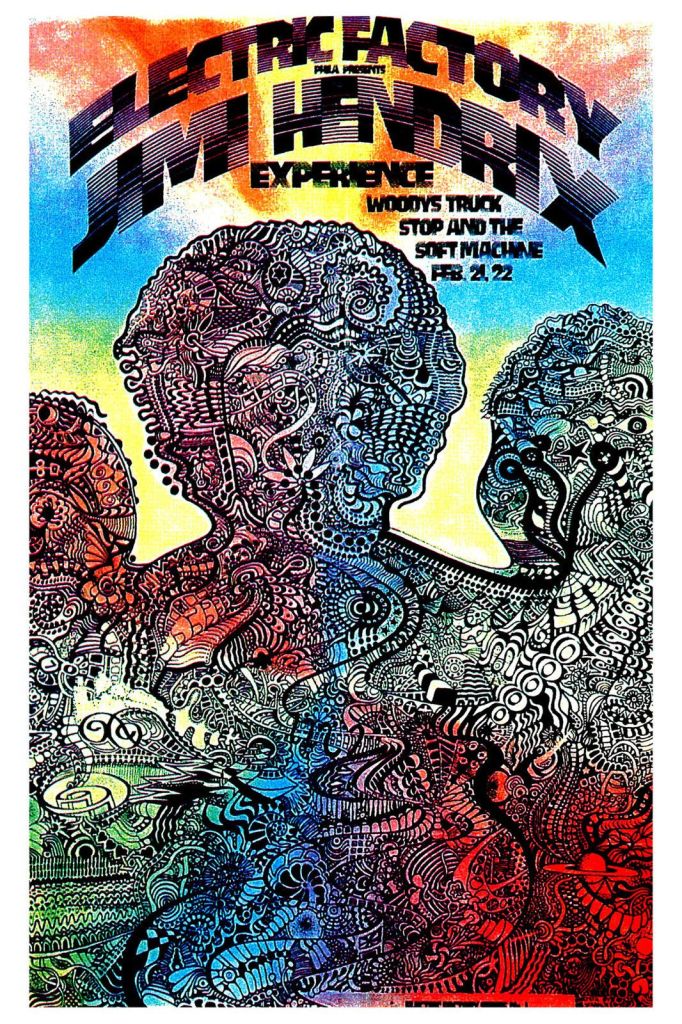

But I did have a foundation that most kids my age didn’t. Glenn himself got into rock at an early age — “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and the Beach Boys’ “Fun Fun Fun” were a couple of the first records he bought, aged 11. By the time he was 15, he was going to concerts at Philadelphia’s Electric Factory, seeing such greats as Jimi Hendrix, the Who, and Arthur Brown.

My parents were indifferent to rock music, and what they might have thought if they’d actually seen Hendrix humping his guitar, Pete Townshend smashing his guitar (as he did when Glenn saw him), and Brown running around in a fire-breathing helmet couldn’t have been good. It’s to their credit, however, that they didn’t try to stop him—and, later, me—from listening to whatever they wanted. If I remember right, they even gave him and his friends rides to those Electric Factory shows when he was too young to drive.

That meant there was rock around the house, if not quite around the clock, a lot more than most other five-to-eight-year-olds had in suburban Philadelphia in 1967-70. He had plenty of singles, sometimes stored sleeveless in those wire racks that did so much to scratch and scuff the vinyl, and lower their financial value to future generations. By the time he entered college in fall 1970, he owned somewhere between 100 and 200 albums, to the best of my recollection. And when he wasn’t listening to what today we might call hard copies, he often had the FM radio on, underground rock emerging as a force on local station WDAS (and slightly later WMMR), as it was in cities throughout the US.

He and friends also managed to make fairly high-quality reel-to-reel tapes off turntables and, somehow, even off the radio by figuring out how to plug something into the back, years before the cassette and higher-tech stereos would make the process much easier and more painless. I’m not aware of any campaigns by the music industry insisting that reel-to-reel home taping was killing music, but the concept was much the same—friends sharing and filching whatever they could.

Yet this wasn’t done out of any sense of piracy or malice, as the RIAA contends every time technology allows duplication and distribution without a cash exchange. It was simply to acquire and enjoy whatever they could, when very limited budgets meant they couldn’t buy all several dozen or so cool LPs that were seemingly generated on a monthly basis as the album overtook the single as the main commercial and artistic format for rock music. That also meant ordering Columbia Record Club freebies under a series of false names (“Ziggy Gormley” was a favorite) until my parents caught on and put a stop to it. That scene in the Coen Brothers’ A Serious Man where much the same thing happens wasn’t just made-up whimsy (though they unfortunately got the chronology wrong—you couldn’t order Santana and Creedence Clearwater Revival albums in 1967, the groups not having yet released anything). The same thing was likely happening in middle-class homes all over America—and, probably, often in Jewish middle-class homes, as ours was, and the one in the film was as well.

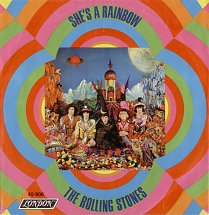

If his record-buying budget was limited, as an eight-year-old too young for an allowance, mine was nonexistent. Hearing rock that wasn’t playing on the radio involved its own form of nefarious sabotage. For me, it was playing Glenn’s records when he wasn’t around. He was pretty tolerant if I wanted to play his singles, maybe feeling he, like many teenagers verging on college, was outgrowing the seven-inch medium. So I got to hear most of the Rolling Stones’ classic 1965-68 hits as 45s, some still in their picture sleeves. I still have a few of them today, and still remember my shock when he told me the blond guy in those photos, Brian Jones, had recently drowned in his swimming pool.

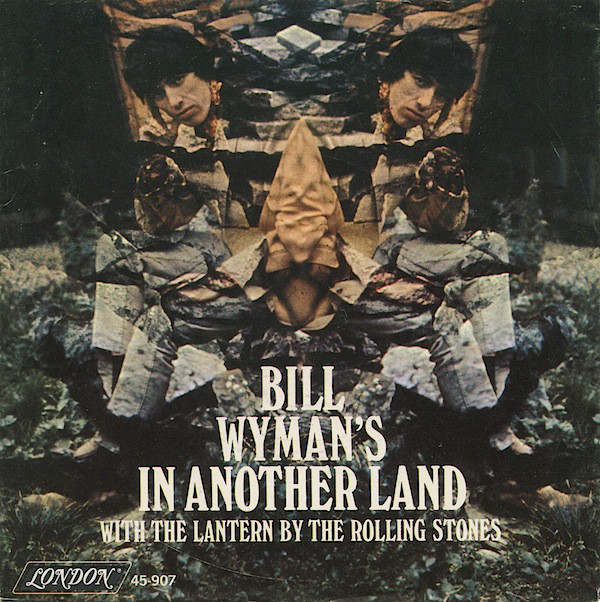

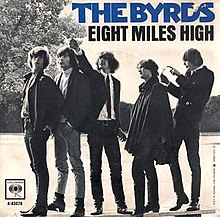

I even still have the one from the Byrds’ Eight Miles High, though it’s pretty tattered and beat-up by now. Before I’d ever heard the record, I loved the image of drummer Michael Clarke bending a spoon behind an oblivious David Crosby’s head, as if he’s about to flick it right into his noggin—something you could believe wasn’t staged, given how much in-fighting there was in the band.

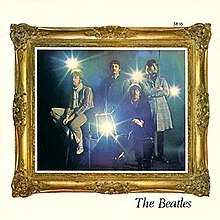

There were also a couple by the Beatles that have unfortunately been lost, and I admit to being guilty of trading the “Strawberry Fields Forever”/”Penny Lane” sleeve for another Beatles rarity. Glenn had been gone from home for a few years by then, and as he was apparently uninterested in moving his collection of 45s with him, I confess to having considered them fair game. But I kept the actual single, of course, playing “Strawberry Fields” over and over again at the height of the “Paul Is Dead” rumor in 1970. It really does sound like John Lennon’s saying “I buried Paul” or “I’m very slow” at the end, not “cranberry sauce,” as John always maintained.

Most of Glenn’s bedroom walls were covered with photos from Sports Illustrated, but he put up a few 45 sleeves too. Collectors may cringe at the prospect of slapping these onto a wall with scotch tape and such when they’d now command some money if they were in mint condition. But then he wouldn’t have had the pleasure of looking at the Dave Clark Five’s “Try Too Hard” every night, or the Beatles’ “Yellow Submarine”—the first image of the foursome I remember seeing.

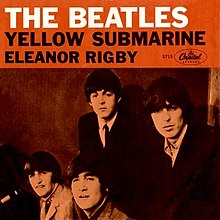

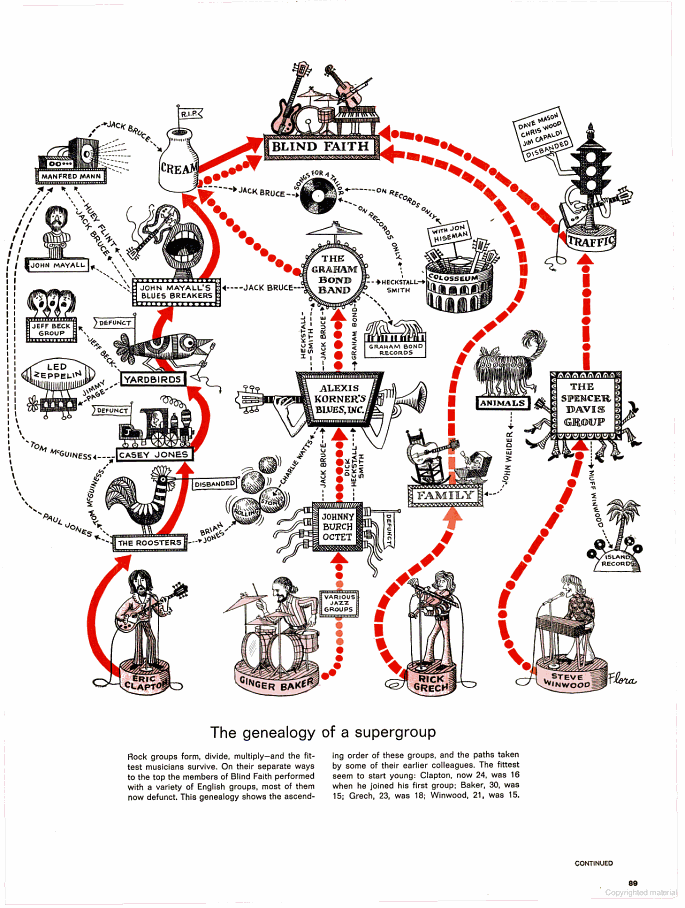

Or the Blind Faith family tree he also posted on the wall, which intrigued and baffled me with its lines connecting Eric Clapton from the Roosters and Casey Jones & the Engineers to the Yardbirds, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, and Cream; Stevie Winwood from the Spencer Davis Group and Traffic; Ginger Baker from the Graham Bond Organisation and Cream; and the non-superstar of the quartet, Family’s Ric Grech, who looked like a tacked-on leftover in such company. He must have torn this out of the October 1969 issue of Life magazine, after everyone else in the family was done with it.

If only in retrospect, some of his most valuable 45 finds came in those bargain bins where Woolworth’s and the like would toss flop singles for a dime or so. Or you could buy a ten-pack for a dollar, the downside only being able to inspect the top and bottom labels, the other eight remaining unknown until you’d parted with your bill. Few suspected that many of those cheapo turkeys would be sought-after rarities decades down the line. Not too many survived in his bedroom drawers by the time I got into college and scoured them for goodies to play on my college radio show, but here are a couple:

Yeah, the Music Machine’s “The People in Me” did make #66 on the national charts, but I didn’t hear it on oldies radio (or anywhere else) once before I spun Glenn’s copy. And it’s a great song, as are a good number of their other singles, despite their unfair stereotype as a trashy one-hit wonder.

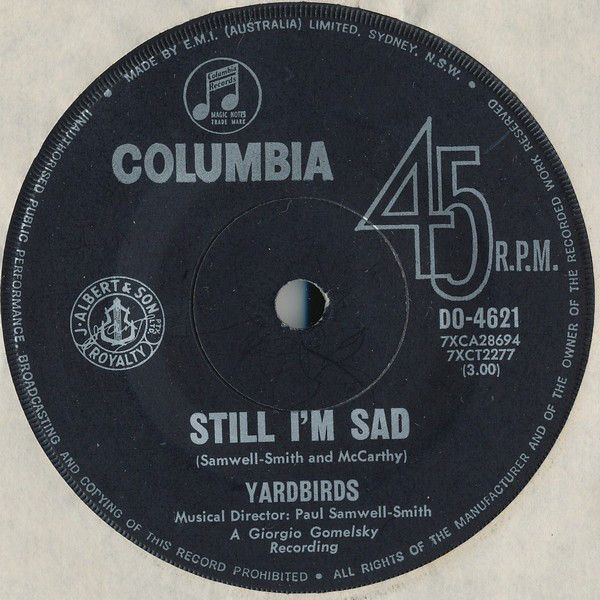

I’ve always wondered how this UK import 45 made it into his collection. Imports of any kind were hard to come by in the mid-’60s, especially singles:

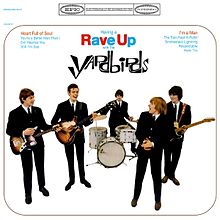

Sure, both of these songs wound up on the Yardbirds’ Having a Rave-Up LP (more of which later), but both are great classic moody Jeff Beck-era cuts. And “Still I’m Sad” has a super-brief strange garbled voice at the end I haven’t heard on any other versions.

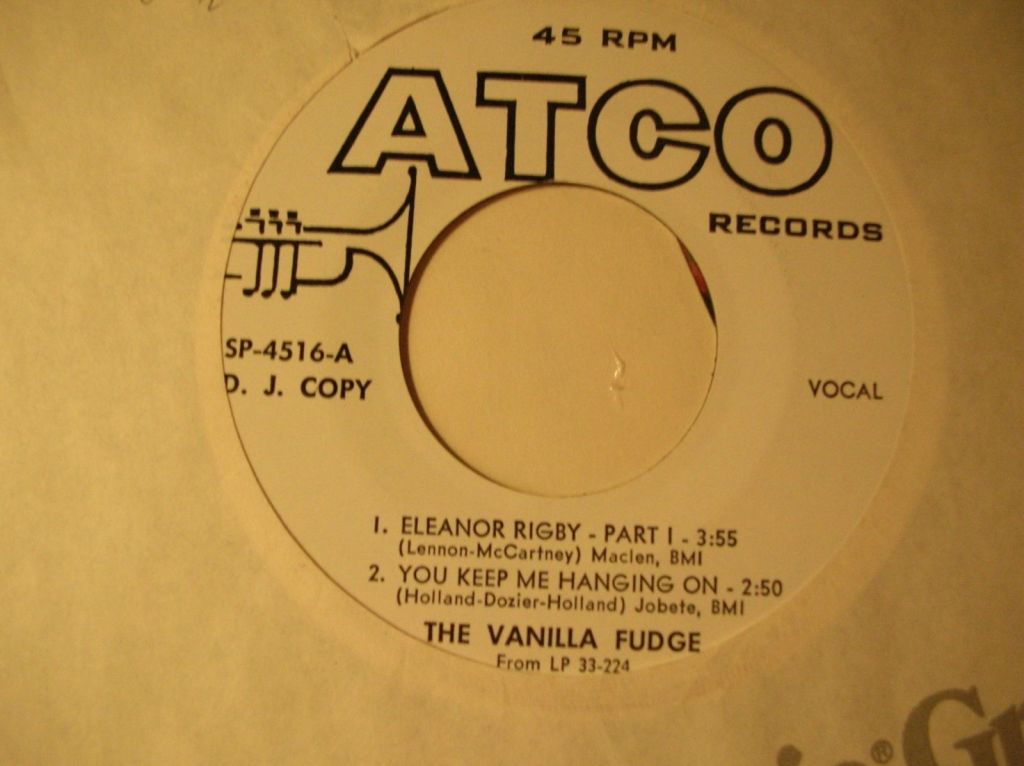

I’m a little sorry I didn’t keep a couple more obscure seven-inches he somehow came across, even though I didn’t think the music was that great, and even though the music is easy enough to call up now. One was by the Chicago Loop, the short-lived group that featured Stefan Grossman and Barry Goldberg. Another was this weird Vanilla Fudge EP:

EPs of any sort, of course, were by the late ’60s rarely issued in the US. I’d never seen one before looking at this as an eight-year-old in 1970, and was kind of weirded out by it. Apparently this was a promo-only release, and I wonder how he managed to get a DJ copy. That was something else that probably found its way into the bargain bin, or grab bag ten-packs.

Another 45 I somewhat inherited of which I have particularly fond memories is hardly a rarity. “Light My Fire” was one of the highest-selling, and one of the greatest, #1 hits of the ’60s. It wasn’t until tenth grade that I got curious enough to play the B-side. It was no small task to do so, by the way. Remember how 45s might accidentally chip at the edges, as if a mouse had bitten off a piece? This one did, though not quite chopping off the soundless groove before the music. You had the put the needle on it very carefully if you didn’t want it to slip off the vinyl onto the turntable, followed by that excruciating high-volume scrape against the spinning wheel. But if you managed to get it onto that sliver of space where it would stay on the seven-inch, you were rewarded by “The Crystal Ship”:

And when I heard it, I went, WOW! I played that quite a bit in the fall of 1976, when, as hard as it might be to imagine today, the Doors were seldom heard on the radio anymore. It stoked my hunger for more, starting with a greatest-hits collection, but quickly moving on to the self-titled debut album on which the track had first appeared. A few years later I had all the Doors albums; eventually I’d have dozens, if you count all the archival live/rarity releases, box sets, and bootlegs; and now I’m developing a six-week adult education course on the Doors. Glenn’s single is echoing on my work more than four decades later, and I never did tell him what he’d inadvertently started.

What about Glenn’s albums? Well, 100-200 LPs might seem like a measly collection today, but it was pretty big for a teenager in the late ’60s. It does seem like the way we collected records was different. When I got really into groups, I’d really get into them, collecting as close to their complete work as I could, or at least as close to a complete work of what I’d consider their only worthwhile era. That started with the Beatles (everything), went on to the Rolling Stones (only their ’60s material), and eventually on to cult groups like Love (only their first three albums). Glenn’s method looked patchier, maybe because he could fill some of the gaps with his reel-to-reel comps. He had just two Beatles albums (Beatles ’65 and Sgt. Pepper, in retrospect a peculiar tandem), for instance, though he had the entirety of some others (The White Album, Abbey Road, Meet the Beatles) on those homemade reel-to-reels, where he also placed much of their other material and non-LP singles here and there.

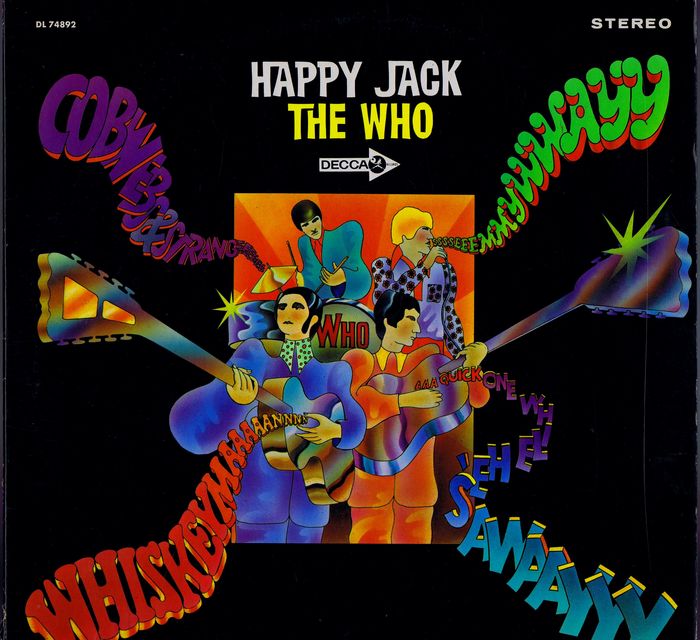

The only relatively “complete works” sections I recall were for Jimi Hendrix—he even had that lousy album of stuff Jimi recorded with Curtis Knight before getting famous, maybe taken in by its deceptive marketing as a “new” or “real” Hendrix album—and Cream, whose short career made the task easier. He had most of the Who through Who’s Next too, and before I really knew who the Who were, I delighted in the Happy Jack (as it was titled in the US) LP’s daft instrumental “Cobwebs and Strange.” It was impossibly silly and, as I remember, a performance at which Glenn always laughed, though he must have heard it many times before he played it a few more for his younger brothers’ benefit.

Some of the records intrigued me by their covers and titles alone, long before I really paid in-depth attention to the music. One was The Worst of Jefferson Airplane. It was actually a best-of collection of sorts, of course, but the irony was lost on an eight-year-old. Why in the world would anyone put out a comp of their worst stuff, I thought? And what was the beyond-weird instrumental “Chushingura” doing on it? (Actually, I still wonder WTF it was doing there.)

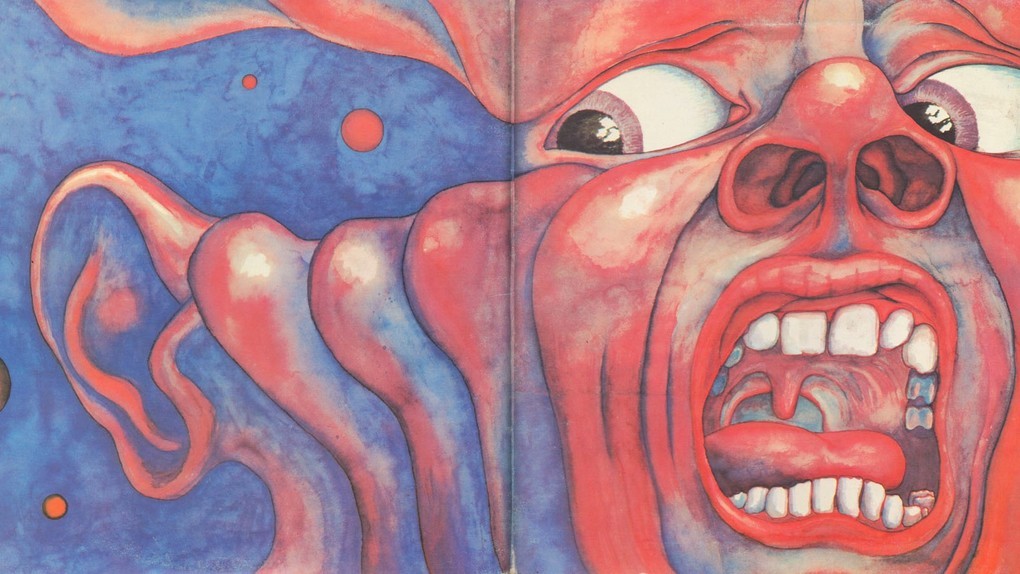

Then there was the cover for In the Court of the Crimson King—as guaranteed to give a young guy nightmares as the scariest episodes of Night Gallery. The record was as good as the cover, but I wouldn’t fully appreciate that until I got my own copy almost a decade after its release. Glenn had their second album (In the Wake of Poseidon) too, which also had good eerie artwork. Artwork, I dare say, much more interesting than the record itself, which was neither too similar to nor nearly as good as its predecessor:

The cover for King Crimson’s second LP, Wake of Poseidon (bottom), was almost as good as the cover for their debut (top), but the music wasn’t half as memorable.

Aficionados of private pressings, small local labels, rare indie discs, and the like will be disappointed to hear that he had little in the way of product by bands known primarily in his city or region. There were a couple of exceptions, though these were of the most renowned such groups. There were albums by the Nazz and Mandrake Memorial, both of which were by far the most successful acts of the psychedelic age from Philadelphia, a town with a fairly meager white rock scene considering its status as one of the five most populous cities in the country.

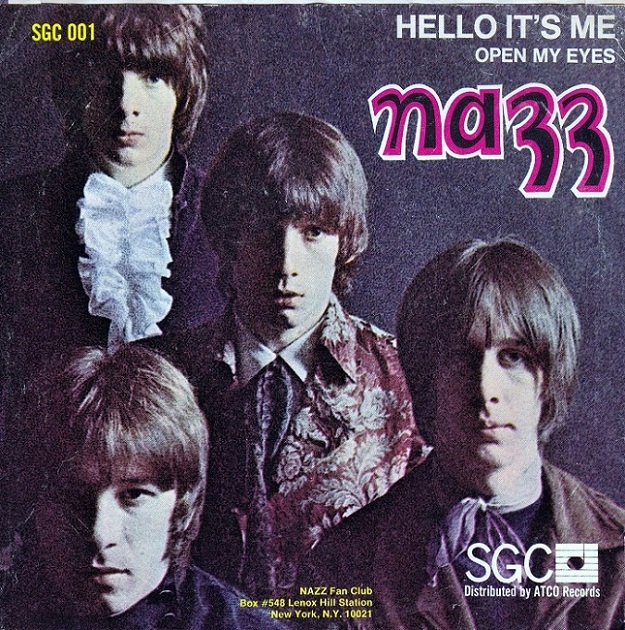

Neither of those bands made much of a nationwide or for that matter global impact, though they were quite popular in their hometown, and Nazz leader Todd Rundgren of course went on to a still-ongoing career as a solo star. They often appeared on bills with much bigger touring acts, and I wonder if that helped Glenn become aware of them, though they got their share of radio airplay too. Especially the Nazz, who actually had a big double-sided local hit with “Hello It’s Me”/”Open My Eyes.” That single only got to #66 nationally (with the B-side charting at #112 in its own right), but must have been big in Philly, as I remember it getting quite a bit of airtime on AM radio shortly after I started listening (yes, I was able to listen to AM radio at night in the late 1960s, as young as I was).

So big was it that I assumed it must have been a hit all over the country, but it was one of the later examples of the regional variation in sales/airplay that’s now far rarer in the US. Wikipedia informs me “Open My Eyes” was a #1 hit at WMEX in Boston, and that both sides were often played in late 1969 and early 1970 on Philadelphia FM station WMMR by Michael Tearson, who went on to a very long career at that station and Sirius XM (and whom I often listened to in the ’70s, not suspecting that he’d become familiar with my writing and eventually meet me for dinner in 2010).

This won’t fly well with some ’60s rock fanatics, but I think those two songs were by far the best Nazz cuts—which, before anyone gets angry, were two more great tracks than most groups manage to come up with in their entire lifetimes. When Rundgren had a big solo hit with “Hello It’s Me” a few years later, I not only thought the remake notably inferior to the original, but was astonished that no one I knew—remember, these would have been junior high students who were seven years old or less when the Nazz version came out—seemed to be aware of its existence.

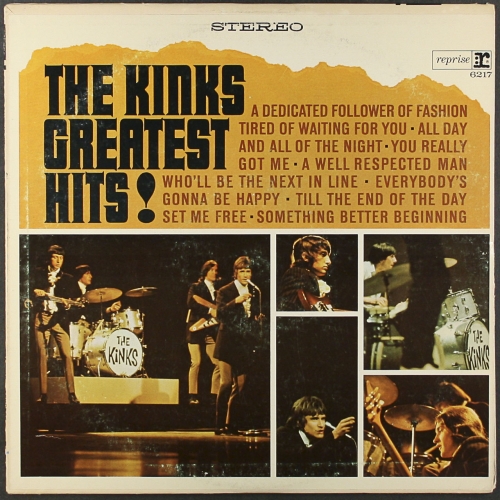

Years after Glenn was gone at college, he stopped schlepping his LPs back and forth. To my memory, for his last year or two at school, he left most or maybe even all of them at home. Although I probably was supposed to keep my hands off, I seized the opportunity to audition quite a few records on my own, mostly British Invasion discs. So it was I got my first extended exposure, via best-ofs, to Gerry & the Pacemakers, the Animals, and the Kinks.

I quickly determined that Gerry and his gang might have come from the same town (Liverpool) as the Beatles, but weren’t nearly as good—not one-tenth as good, in fact, and (unlike the Beatles) pretty nerdy. The Animals (whose “House of the Rising Sun” I’d already heard and enjoyed plenty) were much better, but I was mystified by the liner note’s backhanded slight against the Beatles—”my mother, who follows the pattern of most mothers, is now an avid fan of the Beatles (they’re clean).” The Kinks were real kool, especially that berserk guitar solo in “All Day of the Night.” I never could have predicted that more than 40 years later, I’d have the opportunity to interview the guy who played that solo, Dave Davies, for hours.

And there were three albums by the Yardbirds, highlighted by Having a Rave-Up with the Yardbirds, side one of which (as was written by someone else years before I became a professional writer) is one of the best LP sides of studio tracks recorded by anyone. All of those songs featured Jeff Beck as lead guitarist; somehow, though Beck was in the band when the album was released, all of the songs on side two were older live recordings (first heard on the UK LP Five Live Yardbirds) taken from 1964 performances by the man Beck had replaced, Eric Clapton. Even then, when I was 11 or whatever, I thought it was a weird juxtaposition, and pretty obvious the Beck era was a significant upgrade. I thought better of the live Clapton cuts when I was finally able, in 1979, to hear the Five Live Yardbirds album in its entirety, instead of just the half airlifted to fill out a US longplayer.

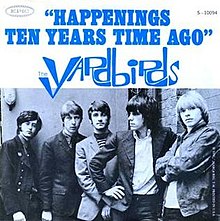

But getting back to Glenn, the other two Yardbirds LPs occasioned some of the more embarrassing faux pas of my early record collecting career. One of their greatest achievements, the 1966 single “Happenings Ten Years Time Ago” (one of their few recordings from the few months in which both Beck and Jimmy Page were in the lineup), was for many years unavailable on LP. Except, that is, on their Greatest Hits compilation. Which Glenn had, though by the time I realized you could only hear it there, it wasn’t there. It was in DC, where he had in fact relocated his entire collection by the mid-’70s.

On a visit my parents and I made to the suburban DC apartment where he was living with his wife while I was in high school, I took advantage of his invitation to play anything I wanted. I went right for “Happenings Ten Years Time Ago,” thinking that the stereo was set up so it would only play through headphones. It wasn’t. My parents came running out of their guest room—everyone else was getting ready to go to sleep—commanding me to turn it down, or better yet, off. Suitably chastened, I did quickly figure out how to cut off the main speakers and listen to it through the headphones. Certainly no one else was demanding to hear the whole track, which was discontinued long before it even got to the atomic guitar solo.

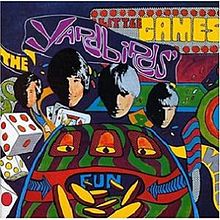

The other Yardbirds album was Little Games. Their only studio LP with Jimmy Page as lead guitarist, I found it just as disappointing as reviews of it in rock encyclopedias had led me to expect, though a few of the cuts were fairly-to-very-good. Glenn kindly said I could borrow it, though it ended up being an, um, permanent loan, as I never did get around to returning it. It’s not the proudest moment of my record collecting career, even if it’s a practice, in all honesty, I never did repeat. But it does testify to our shared passion for the band, Glenn telling me about 20 years later that he was reading a Yardbirds bio online, agreeing with its assessments, and thinking the critic really knew their stuff—and, arriving at the byline on the bottom, realizing it was written by his youngest brother. Validation!

Going back to 1970, Glenn would occasionally let me and my other brothers hear some of the music he’d taped onto reel-to-reels off friends’ turntables and the radio, but didn’t have on vinyl. I still remember the thrill of hearing Meet the Beatles and getting, although this lingo was not yet in common use, blown away by the sheer quality and variety of songs. Shortly afterward, I’d make Meet the Beatles the first album I owned, asking for it when I was entitled to a present of my choice (the only way for an eight-year-old could obtain such an item).

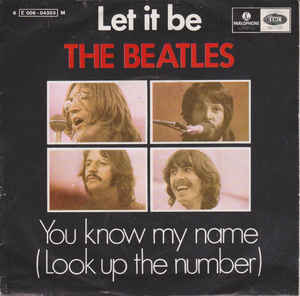

By this time a senior in high school, Glenn was noticing I’d be playing records on his equipment when he wasn’t around, his complaints leading my parents to buy me a cheap turntable of my own—not the most graceful way to get something I wanted, but another testimony to our shared fanaticism for rock’n’roll. At least by that time, I had the Beatles’ “Let It Be” single—with its (then) seldom-played B-side “You Know My Name,” which we’d laughed at together when he played it off a tape, I incredulous at its sheer strangeness, a la the Who’s “Cobwebs and Strange.”

Also on reel-to-reel was The White Album, which as mentioned he consented to play for us from top to bottom, though just once, in part because that took a good hour and a half. That led to another of my not-too-proud-to-remember stolen-music moments, when I and another brother determined we could listen to this reel-to-reel on our own when neither he nor our parents were home. It didn’t take long, naturally, for Glenn to discover we were doing this—maybe we stored the tape tails in instead of tails out, or something like that. That was the end of our secret reel-to-reel session, and I might have been too embarrassed to ask him to play me anything off the reel-to-reels after that.

As long as we’re on the Beatles, by the way, I recall Glenn telling me in early 1970 he’d just heard a new Beatles single on the radio. This was right before or around the time they were breaking up, and also just after I’d become a Beatles nut, trying to hear or find out anything I could about them. This was more exciting news than the arrival of the Messiah, and I excitedly pressed him for more details.

To my surprise and disappointment, he was kind of vague and lukewarm about what he’d heard, only able to comment that it was kind of like a cowboy song. This wouldn’t have been the Beatles tune most likely to fit that description, “Rocky Raccoon,” which had been on The White Album (which he had, if only on reel-to-reel) for more than a year by that point. I wonder if it was “For You Blue,” the George Harrison-penned-and-sung number used as the B-side to “The Long and Winding Road,” the first posthumous Beatles single. That’s much more of a blues than a cowboy song, but it does have kind of a loping, galloping feel.

Glenn had many reel-to-reels, at least several dozen I think, which were double-sided, probably accommodating about two hours of music each. The tracks on each were meticulously and neatly handwritten, amounting to his generation’s equivalents of what we’d call “mixtapes” when cassettes came into vogue. Amongst the expected songs by the Beatles, Traffic, the Doors, and the like were real oddities, at least in that company, that never got too much sales or attention. There were, for instance, items by the Beacon Street Union and Earth Opera—maybe they were getting airplay at the height of the “Bosstown Sound” hype.

You could also tell when he didn’t care much about some acts others would consider legendary. There was very little Bob Dylan, for instance (I remember “Positively 4th Street” was on one of them), and if you’re thinking he didn’t want to duplicate material he had on vinyl, he didn’t have any Dylan LPs or singles. There was just one Velvet Underground cut, “White Light/White Heat,” though in fairness they were not getting much airplay or sales at the time, and far less known than, say, Traffic, or maybe even (in Philadelphia, anyway) the Nazz.

These tapes were eventually left behind at home when he went to college, and, unlike his LPs, not destined to travel with him when he married shortly after graduation and moved to DC. That meant I was at liberty to play those reel-to-reels without fear of punishment. Alas, the relatively cumbersome task of threading it onto a machine and cueing up to the songs I wanted meant I did little of that, at a time when I did have some of my own vinyl to play. I do remember finding and playing the early Beau Brummels hits “Laugh Laugh” and “Just a Little” on one of those tapes. But eventually they’d be thrown out, their only use in the digital age as documentation of what one teenaged rock fan was listening to back in the late ’60s, as captured on those handwritten tape boxes.

So after all this early exposure to music we both loved, did we end up getting the same things in collections that expanded to thousands, comparing notes on new discoveries? No. As far as I could tell, his shelves of discs grew little after the early 1970s. There were other, newer interests occupying his time. Those included working as the sports editor on the University of Pennsylvania’s paper, preparing for application to graduate school, and, most significantly, meeting his future wife, Alyse, whom he married in 1975, spending the last 45 years of his life with her.

Eventually much of his passion resurfaced, especially when he was able to play the music for his two now-grown sons (one of whom, my nephew Andrew, now writes for Billboard magazine). In turn, my nephews made him aware of much more contemporary music. Even if he never took to twenty-first century sounds with quite the energy he gave to ’60s rock, I remember being surprised when he mentioned listening to the Decemberists in his office.

It’s also worth noting that during this entire period he, like millions of young American men, was under threat of getting drafted to serve in the Vietnam War. When the draft changed to a lottery system, his birthdate, December 4, drew #1—meaning he was in the very most likely group to be inducted into the military. Like many young men of the time, he had a college deferment, and the draft was thankfully eliminated in 1973, well before his graduation.

I bring this up not only because it might have complicated his record-collecting life, but also because he’d played Country Joe & the Fish’s “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag” for me back in the late 1960s. Back then as a six- or seven-year old, I’d laughed at its sheer jovial novelty, much as I’d treated “Cobwebs and Strange” and “You Know My Name.” It is a funny song, but I was oblivious to the quite serious issues it was satirizing in lines like “be the first one on your block to have your boy come home in the box.” Glenn was laughing too, but it must have been a nervous laugh, knowing even at the age of 15 of how that might happen to him or people he knew.

Much later, my parents and I (without Glenn) visited the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in DC, shortly after its 1982 opening. I’m grateful his name was not on it. As many now remember, the memorial was quite controversial when it was unveiled, in part because it seemed to be burrowing into the ground. While my family was liberal and opposed to the war, they had not expressed their opposition (or strong political opinions of any sort) too vocally or angrily, at least in my presence. But talking about how the memorial seemed to be going into the ground sparked an uncharacteristically blunt remark from my mother, who blurted, “That’s where that war belongs.”

Fear of losing her first-born son was still fresh nearly a decade after the draft was abolished. By that time those were sentiments with which I wholeheartedly agreed, even if that’s now tempered with acknowledgment that we must remember what happened if we’re to avoid such tragic waste in the future.

By this time, in many ways my knowledge of music from this era was surpassing Glenn’s—not just because my collection had grown into the hundreds, but also because of my voracious appetite for finding out anything I could about rock history. Eventually it would grow into the thousands, and I’d write a dozen or so rock history books. Now I’ve taught adult/community education courses on rock history, on almost a dozen different subjects.

This isn’t to say I was smarter than him, or even that I was more passionate about the music of the time. But unlike him, I made it a big part of my life’s work, discovering acts—let’s take the Pretty Things, as one of the more celebrated examples—of which he and most Americans were totally unaware of in the ’60s. Or even “deep tracks” (a term not in common use back in the day) by stars he was well aware of, from the Kinks and the Byrds to the Who and Hendrix. Although I was pleasantly surprised to learn from a close friend of his, the evening of Glenn’s funeral, that he actually was a fan of the Move—a group barely any more familiar to Americans than the Pretty Things, though they had numerous UK hits.

It’s fitting that the last time I saw Glenn this year in San Francisco, where I live, we spent hours talking about music and baseball, passions he shared and handed down with so many of his friends and relatives. But the most important inspiration Glenn gave to me wasn’t about rock’n’roll, sports, or his many other interests. It was in the way he lived his life, always thinking about others before he thought of himself; committing good deeds for his family, community, and at his workplace; and doing so with such humility, never making those around him feel like he was doing them favors or expecting any in return.

For Glenn, practicing good values was part of his daily life, whether shouldering much of the responsibility for taking care of my parents in their final years; speaking about the importance of environmental sustainability at his synagogue; or, yes, not losing his cool when his eight-year-old kid brother listened to his records and tapes when he wasn’t at home, even though I knew I wasn’t supposed to do that. He was gone too soon, and we’ll miss him every day. But the way he put his principles and his passions into his life will always be with me, and, in an apt footnote, continues to be heard today.

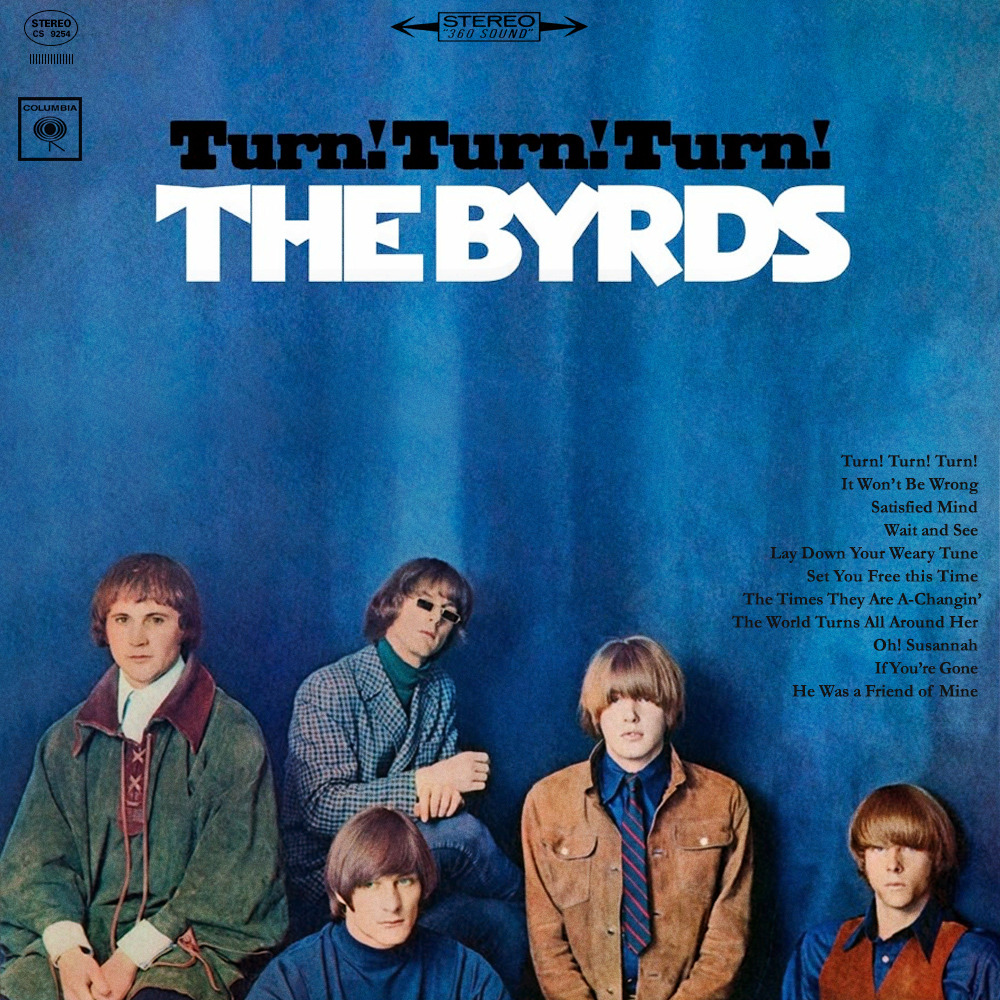

At his funeral service, the rabbi mentioned Glenn had read from the Book of Ecclesiastes just a couple weeks ago, and quoted the very lines Pete Seeger adapted into “Turn! Turn! Turn!”—a song that, in turn, the Byrds turned into a #1 folk-rock hit. A song that, as it happens, I used as part of the title of one of my books, Turn! Turn! Turn!: The 1960s Folk-Rock Revolution.

And that evening, one of his closest friends told me how Glenn won a coveted prize at a party back in the mid-1960s: the Byrds’ second album, also titled Turn! Turn! Turn! It was a time, he explained, when getting any LP was a big deal for a 13-year-old with little disposable income, let alone a good album by one of the top bands of the era. And then I remembered Turn! Turn! Turn!‘s continued presence, years later, in his library of albums.

Glenn’s voice continues to echo in my life and work. He continues to speak to me, even today.

such a loving and poignant remembrance; am the same age as your brother with three younger brothers who also absorbed my music passions, a highlight being three of us seeing Van Morrison in Houston together in 1974; most of your memories ring true to me as well; was such an incredible era, and growing up ’45 minutes southeast of Thibodaux, Louisiana’ we had New Orleans as our base inspiration; my condolences on your loss.

Wonderful tribute. I also had a rock mentor, my Uncle Peter, though he didn’t know it. Peter also died recently, at age 74. He went to Georgetown, Class of 1968 (Bill Clinton was a classmate and hosted their 25th reunion at the White House; the Righteous Brothers provide entertainment). In the early 1970s, I found his college-era LP collection at my grandparents house in Yonkers, NY, including Cream’s “Disraeli Gears”, Stones’ “Aftermath”, the first Doors album, Byrds’ “Fifth Dimension, Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds and many others. I wore out the grooves on those albums and they provided me with quite an education. However, Peter wasn’t interested in talking about music when I attempted to enrage him. Rock was probably just a passing fad for him, but not for me. Getting back to your tribute, the Let it Be “cowboy song” he was referring to probably was “Too of Us”. I thought the same thing when I first heard it. Also, re the “8 Miles High” cover with Michael Clarke and David Crosby, in case you never heard their argument while recording “Notorious Byrd Brothers, check this out. Both hilarious and illuminating about a band falling apart: https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=y7S9wA5vV4Q

It could well have been “Two of Us.” I was confused by his inferring it was a single, but maybe it was a cut off the Let It Be album (or even one of the bootlegs of Let It Be material that came out before the LP) that was introduced as a new Beatles song on the radio right after it came out.

This is a wonderful tribute to your brother and also is an interesting story about you. There are not many boys who hold on to a passion from their youth. Not only did you bond with your brother around music but you kept expanding your collection and your knowledge to such an extent that you are now an expert.

I know from experience that writing is a valuable process in dealing with such a loss. It helps you face the trauma and feel the sadness. My sympathy to you and your family. May his memory be a blessing.

Very nice, Ritchie. I lost my only, younger brother here years ago and I can empathize with you on the pain of the loss. Keep up the good work, on both your own and your brother’s behalf.

Excellent writing. Excellent article. Excellent tribute.

I just skimmed your beautiful tribute to your brother, You have my sincere condolences. I was intrigued because my husband will be 64 soon, having grown up in Wayne on the Main Line and having similar interests as your brother in musical tastes. Most obvious, Nazz, which my husband displays an album cover in our family room which Todd signed approximately 3 yrs ago and dated it ahead! He played in our town at the time. Also, my husband saw many upcoming artists at U of Pitt which he attended. It sounds like your brother has influenced your life immensely, and that in itself is a beautiful thing. Again, so sorry for your loss.

This is a beautiful tribute to your brother. But it’s also an education in the ways you and your brother immersed yourselves in a rich and vibrant musical culture. Though I never met Glenn, I feel that he, through you, made a lasting impact on my life. These memories of your brother will stay with you to the end of your days. I’m grateful for what you have shared with us.

A lovely tribute to your brother…as a 65 year old life-long Philadelphian, I can’t help but think your brother and I were at some of those same shows at The Electric Factory…wonder if he ever made it to The Trauma, which pre-dated The Factory by a bit and had great shows and Mandrake Memorial as the house band… Thanks for sharing your memories.

Dear Ritchie: My condolences on the loss of your brother. I’m the same age as you & my two siblings are 11 & 9 years older than me so I got my music interests just like you through my sister’s Beatles records & listening to the radio. My brother-in-law also had the albums you mentioned (Jefferson Airplane, Country Joe, the Yardbirds) that I listened to when I baby sat for my niece. My brother had such albums like Frigid Pink, Lord Such & Heavy Friends w/the Union Jack bedecked Rolls Royce, that 1st King Crimson album, Sssh by Ten Years After & Everyone’s In Show Biz by the Kinks which he bought after he saw them play in the Music Hall in Boston in 1972 & which became my 1st Kinks album (“Hot Potatoes” remains one of my favorite Kinks songs). I’m very sorry for your loss & thanks for your great tribute to him

Very sorry for your loss. Like you I had an older brother whose musical tastes heavily influenced my own. He was always a step ahead, listening to Dylan while I was in love with the Four Seasons, bringing home King Crimson LP’s while I searched for Cowsills 45’s. We both loved The Beatles, and I remember him making a vow to buy every Beatle records when he got his first job, a vow he kept a few years later.

It’s difficult explaining to younger people how important music was to our generation, especially without giving in to the impulse to tell them how much better “our music” was. That argument is unwinnable and rightfully so. And how do you adequately describe a world of transistor radios and teen magazines and Beatle wigs and record stores and AM Top Forty radio? It sounds mundane, but we all know it was the farthest thing from mundane.

Your tribute to your brother was simply magical. It told his story in a beautiful way, and I think it reminded many of us of the wonderful way that music connects people. Thanks for that.

Hi—I was thinking about Glenn and happened across your article. He and I were roommates at Penn for a year, maybe 2. He was such a fine man. Thank you for the memories.

Thanks for your note.