As I wrote in a post a while ago, Candlestick Park, former home of the San Francisco Giants, is due for demolition pretty soon. That got me thinking of other major league ballparks I’ve been to that no longer exist. There aren’t that many – Connie Mack Stadium (Philadelphia Phillies), Veterans Stadium (also Phillies), the Kingdome (Seattle Mariners), Memorial Stadium (the Baltimore Orioles, which I only went to once), and the old Yankee Stadium (also only visited once).

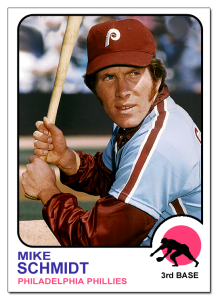

Since I grew up in the Philadelphia suburbs, I know Veterans Stadium by far the best of these parks, though I never went there after moving to the San Francisco Bay Area in the early 1980s. Retrospectives of the Vet, as it was known locally, emphasize the most famous moments – the 1980 World Series victory, the feats of Hall of Famers Mike Schmidt and Steve Carlton, the 1993 pennant with rowdy characters like Lenny Dykstra and John Kruk, and colorful glove-thumping of reliever Tug McGraw, and Pete Rose coming to the Phillies for a few years near the end of his career. This post, though, will recap some of the odder moments of Phillies baseball I saw in person, none of which are likely to get much if any coverage in baseball books.

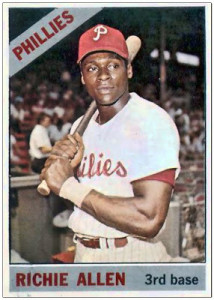

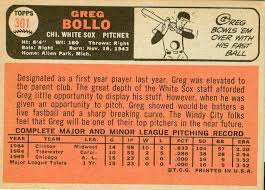

As a preamble, the very first major league games I saw were in Connie Mack Stadium, the facility (formerly known as Shibe Park) the Phillies played in from 1938 to 1970. When I was seven, I saw my first games at a doubleheader against the Pirates on June 22. The Phillies were pretty bad then, and thought of as pretty star-crossed, never having won a World Series, and having blown the 1964 pennant by losing ten games in a row near the end of the season. Their superstar, Richie (later Dick) Allen, was generating enormous controversy for his knack for irritating management and fans (even writing messages to them in the infield dirt), and in fact would get suspended for about a month just a couple days later for failing to show up for games in New York.

Even at that age, I could tell the neighborhood surrounding Connie Mack Stadium was pretty bad, too. Bad enough that you could, even at that age, tell parents were pretty nervous parking around there, which was just one reason the team moved to a much safer (if more isolated) area in the early 1970s.

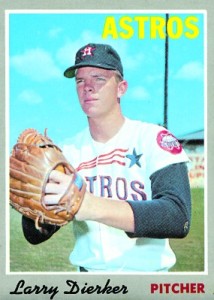

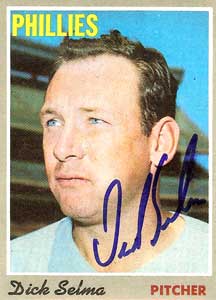

The only two other games I saw were a doubleheader against the Giants in 1970. (My parents were very economy-minded, and if they had to take the family to a ballpark, they’d do it just once a year, and get two games out of the way at once.) The Phillies were still bad, but they swept the twinight doubleheader, though in a fashion that still managed to accent their futility. In the first game, Jim Bunning had the chance to become the first pitcher after Cy Young to win 100 games in both the American and National Leagues. He left a 5-4 lead in the hands of ace reliever Dick Selma, who struck out the first two batters in the top of the ninth (the second of them Willie Mays). Then he faced Willie McCovey, and though I can’t look up the count, as I remember got two strikes on him. And then – McCovey hit a home run. The 100th win for Jim Bunning in the national league would have to wait.

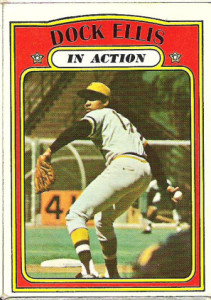

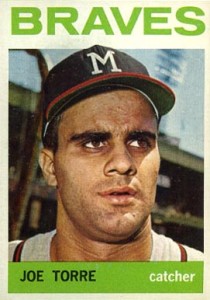

It almost looks like this photo was snapped right after Dick Selma gave up a game-tying homer to Willie McCovey, delaying Jim Bunning’s chance to become the second pitcher to win 100 games in both the American and National Leagues.

Looking back at the Phillies’ 1970 schedule, as you can easily do online these days, I’m struck by how differently games could get bunched up back then. Probably due to a makeup game, the Phillies had also played a twinight doubleheader against the Giants the previous day. And that wasn’t the only time they played doubleheaders on consecutive days that year – they’d done so about a month earlier in two different cities (Montreal and Philadelphia) on July 1 and July 2, that after playing two games in St. Louis on June 28. And dig this – after playing doubleheaders against the Giants on both Friday, July 31 and Saturday, August 1, the Phils would play two-fers against the Pirates August 6 and the Cubs August 9, with no off days the whole while. That’s fourteen games in ten days. Can you imagine the Players Association letting MLB get away with that now?

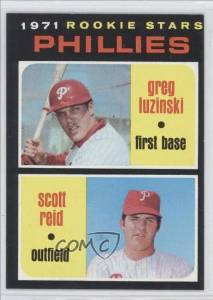

Also, the day I went to Connie Mack on 1970, it actually hosted a triple-header. How’s that possible, you ask? Well, in the afternoon, the festivities started with the Double-A Eastern League All-Star game, the Phillies having a double-A affiliate not far away in Reading, Pennsylvania. Three games in one day was just too much for my parents, and we saw just a few innings of the All-Star game, in which I’m pretty sure future Phillies slugger Greg Luzinski played. What sticks with me the most, however, is that between the double-header and the first “real” game, I saw one of the Eastern Leaguers, still in uniform, on the concession ramp, talking earnestly with a woman I assume was his wife. Can you imagine that happening at a big-league ballpark these days?

When Veterans Stadium was torn down about a decade ago, I was amused to hear it referred to as something of a decrepit, characterless structure. Back when it opened in 1971, it (along with two similar, now-demolished stadiums that opened at around the same time, Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium and Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium) was considered cutting-edge state-of-the-art. Not only was it bigger and safer (and in a safer neighborhood with more parking), it had a big electric scoreboard that showed player stats – still something of a novelty then – and cannons, fountains, and a Liberty Bell that were supposed to go off with Phillie home runs.

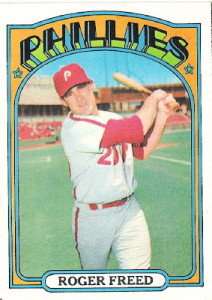

As it happened, our family went to the second game ever played there, against the Montreal Expos on April 11. The Phils’ big hope that year was new right-fielder Roger Freed, who’d been trapped in an Orioles minor league system overflowing with talent. In 1970 in triple-A, he was the International League’s MVP, hitting .334 with 24 homers and 130 RBIs. The Phillies traded one of their starting pitchers (Grant Jackson, coming off a bad year) to get him. There was even a story in a national magazine (Sport, if I remember correctly) titled something like “Freed at Last.” And, wouldn’t you know it, Freed hit a grand slam, setting off all those artificial fireworks we were hoping to see.

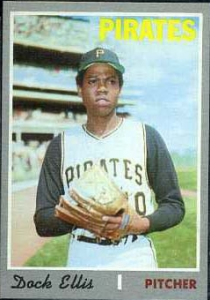

Except, in a portent of things to come, the fireworks didn’t work. At least, not all at once or like the cannon, fountains, and bell were supposed to. The Phillies did win that game 11-4, but Freed turned out to be a bust, hitting .221 with six homers, getting relegated to part-time duty the following year, and returning to the minors the year after that, never playing regularly in the bigs (or at all for the Phils) again. Grant Jackson didn’t exactly become a star, but he was a good reliever for a long time for the Orioles and the Pirates, winning a game for the latter in the 1979 World Series.

Another odd play that sticks out came four years later, when the Phillies had gotten much better and were finally contenders. In the first game of a Memorial Day twinight doubleheader against the Cubs, Mike Schmidt, who’d ascended to superstardom the previous year after a tough 1973 rookie season, hit a triple in the bottom of the first. In the eyes of one of my relatives also at the game, Schmidt – despite his impressive statistics – could do no right, always failing in the clutch, striking out, or making physical or mental errors at big moments. And as if on cue, Schmidt thought about going for an inside-the-park homer, thought better of it, scampered back to third – and got called out. They didn’t score that inning, and lost the game 7-5. I cannot remember another time I witnessed a player getting tagged out after rounding third on a triple and trying to return to the bag.

The Phillies continued to get better, despite this mishap, and got into the playoffs in 1976, 1977, and 1978. But they failed to advance to the World Series each time, and despite adding Pete Rose in 1979, they fell out of contention by late summer. I saw what was probably their last hurrah – a 12-inning walk-off victory against their chief rivals (and eventual world champion that year), the Pirates, in the first game of a twinight doubleheader on August 10. Ex-Met Bud Harrelson, whose acquisition my friends and I had soundly derided, knocked in the winning run with a single with two outs in the bottom of the 12th. The Phillies lost the second game, however, and it wouldn’t be until 1980 that they finally cleared the hurdle to the World Series and, against the Royals, won a world championship.

When I think of the earlier years when the Phillies were struggling to first rise to respectability and then to keep from choking themselves in the post-season, one symbol stands out in greater relief than any other. For opening day, the Phillies would hire this guy named “Kiteman” to sort of ski, sans snow, down a ramp in the stands, lift off into the air as if he was an Olympian ski jumper, and make a parachute landing on the field, hopefully on the pitcher’s mound. The thing was, like the Cone of Silence in Get Smart, it never worked, though they tried it more than once. In fact, on Kiteman’s first attempt (actually the first Kiteman’s attempt, since various Kitemen assumed that role over the years), he kind of skidded off the ramp and crashed in the stands, though fortunately he wasn’t seriously hurt. It wasn’t until 1990, in fact, that a Kiteman made it to the pitcher’s mound.

Nor was having “the Great Wallenda,” tightrope walker Karl Wallenda, walk on a rope suspended high above the field from foul pole to foul pole exactly common between-games (back in the days when there were scheduled doubleheaders) fare. Quite fortunately for all involved, he made those journeys without accident, even standing on his head in the middle of the rope on one televised walk. When Wallenda did fall to his death, it wasn’t at the Vet, but far away, on a walk between two towers in Puerto Rico.