The past few years, there have been just enough rock films to fill out a Top Ten list, and that’s only by slotting in a few movies from the previous year and non-rock documentaries that are nonetheless of interest to me (and hopefully some other rock fans). That’s the case again in 2017, with entries ranging from big stars to sidemen, and rock journalists to a real-life rock’n’roll high school of sorts. (The three films here released before 2017 are noted as such in the reviews.)

If there’s any trend—other than a heartening one toward subjects, such as Native Americans in rock, that likely would been considered too obscure to fund even a decade ago—it’s the increased availability of documentaries primarily or only on streaming services like Netflix or AmazonPrime. For those of us too cheap to pay for them in our home, that means catching up on some of them at homes of friends who can access them, as I did while house-cat-sitting during Thanksgiving. We can complain about these not being available on DVD, but then again, watching a movie always requires some sort of first-world expense or hardware, whether it’s paying for a ticket at a festival screening or having a home DVD player and television (and the electricity to run them).

1. Horn From the Heart: The Paul Butterfield Story. There’s nothing structurally unusual about this documentary about the harmonica player, singer, and leader of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. Nor are there notable surprises for viewers familiar with the basics of his career. And you know, that’s fine. What you get is what music documentaries should deliver at their core: a comprehensive, straightforward, mostly chronologically sequenced overview of a notable musician, with plenty of interviews with close relatives and people who played and worked with him. And the number of interviews the filmmakers landed is impressive, including just about everyone notable who’s still around: Elvin Bishop, Elektra Records chief Jac Holzman, drummer Sam Lay, Butterfield’s ex-wife Kathy, his brother, two sons, Geoff Muldaur, Maria Muldaur, Joe Boyd (about the Butterfield Band at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival), David Sanborn, Happy Traum, Mark Naftalin, and Nick Gravenites among them.

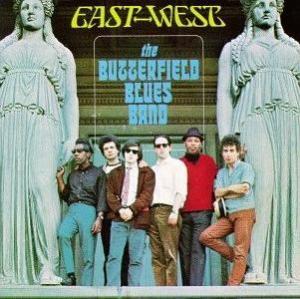

Unfortunately there isn’t a whole lot of film footage from the Butterfield Blues Band in their prime in general, though this documentary includes excerpts from their performances at Newport, Monterey, and Woodstock, as well as some silent home movies dating back to the early ‘60s. Some little known bits of interest to serious fans pop up, like the actual location of the striking cover for the East-West LP, shot at Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry, or that a young Steve Martin shared the bill with Butterfield when the band played the Golden Bear in Southern California. Some of the more colorful memories from the interviews include Geoff Muldaur on Albert Grossman starting a fight with Alan Lomax after the folklorist gave Butterfield’s band a demeaning introduction at Newport (“that’s what a manager should do”).

Another observes that whatever Muddy Waters would have written, Paul Butterfield lived. Unfortunately that included a long decline over the last decade or so of his life, involving serious substance abuse and health problems, and the breakup of his family. But the bulk of the movie is on his better days in the 1960s and early 1970s, even though it doesn’t take the overt stance, as I do, that his most interesting music by far was made in the mid-’60s on his first two albums, when both Bishop and Mike Bloomfield were guitarists in his group. I don’t think Butterfield was a great singer or composer of note either, or at least as good in the non-harmonica playing/bandleader departments as the film’s general tone espouses. But his life deserves this worthy commemoration, though I was a little disappointed there wasn’t an excerpt from his stranger-than-fiction 1966 appearance on the show To Tell the Truth, which you can see at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2HSEDBeeDHg.

2. Beside Bowie: The Mick Ronson Story. If you know a lot about David Bowie in the first half of the 1970s, there won’t be a whole lot that’s unfamiliar in this well-constructed, straightforward documentary of his primary guitarist during those years, Mick Ronson. Still, it’s fun to see and hear quite a few of his associates talking about him, including producer Tony Visconti, Angie Bowie, Rick Wakeman, Lou Reed (represented by archive footage), David Bowie (though seen in archive footage and heard in voiceover), Bowie keyboardist Mike Garson, and Ronson himself (also, naturally, represented by archive footage, particularly a pretty extensive interview from not long before his 1993 death). There are also some key voices missing, such as producer Ken Scott, manager Tony DeFries, and the other Spiders from Mars. His work with musicians other than Bowie is also covered, though not in great depth; likewise his unsuccessful solo career, the film not really addressing its failure due to Ronson’s weaknesses as a frontman/singer/songwriter. There is, however, plenty of footage of Bowie from his glam era as compensation. And if you want at least one perspective that’s unfamiliar, it turns out Ronson hated the Velvet Underground, though his co-production (with Bowie) of Reed’s Transformer was crucial to that record’s success. A DVD version (which I haven’t yet seen) of this has been released with extra features.

3. Long Strange Trip. Not yet available on DVD, but streaming on Amazon Prime (and given a limited release in theaters), Long Strange Trip is a four-hour documentary on the Grateful Dead. Is that too much, or not enough? That depends on how much of a Deadhead you are. Whatever your interest in the band, the movie’s strengths are interviews with all of the founding members save Pigpen (Jerry Garcia represented, of course, by archival clips and recordings), as well as a wealth of footage from throughout their career. With so many Dead fanatics, one’s reluctant to declare that even Deadheads will see some material they’ve don’t know existed. But that seems likely given the abundance of home movies, good-quality color performance clips dating back to the mid-1960s, and excerpts of an unreleased documentary on their 1970 European tour. You seldom see a complete song, but that might be grist for another project.

For all its length, this movie is not a history that covers all the key bases, and doesn’t progress in a linear manner through their career and albums, a la the Beatles’ Anthology. That’s in keeping with the Dead’s nonchalantly “whatever happens” attitude toward much of their lives. But it does mean some events and recordings (the film makes the point that they didn’t see commercially available albums as cornerstones of their work) that even some diehards would consider essential aren’t covered. Tom Constanten, a brief but important member in the late ‘60s, isn’t even mentioned. Nor is Mickey Hart’s extended absence for a few years in the early ‘70s, let alone how his father’s mishandling of the Dead’s management contributed to that. And some of the laudatory comments by committed Dead fans (Al Franken among them) about the relative merits of obscure concert versions of the same song, and the religiously ecstatic experiences of losing oneself in the Deadhead world, will seem weird and borderline-creepy to the unconverted, not to mention tedious at times.

Some key surviving associates and family are also notable by their absence, but the non-member interviewees do often offer illuminating comments and memories. Among them are Warner Brothers executive Joe Smith, early Garcia girlfriend Barbara Meier (who reentered his life near its end, though longterm girlfriend Mountain Girl is a notable absentee), lyricist John Perry Barlow, engineer Dennis Leonard, and tour manager Sam Cutler. There’s also publicist/biographer Dennis McNally, who refreshingly acknowledges that the obsessive tape trading among Deadheads probably doubled or tripled the band’s audience. McNally’s book on the Grateful Dead is the best source for further investigation into the numerous recordings and events this documentary doesn’t fit into its four hours, which do tell many of the most important tales of the band. But it probably won’t convince the undevoted (such as, I admit, myself) to reevaluate and elevate their significance.

4. Chasing Trane: The John Coltrane Documentary. Given a theatrical release and now available on Netflix, this is a 100-minute film on one of the most famous jazz musicians. Yes, this list is nominally a rock list, but I do make room for some other music documentaries of note, and Coltrane did influence some major rock stars. Two of them, Carlos Santana and Doors drummer John Densmore, are interviewed here, though they (and Coltrane’s influence on rock) are not a primary focus of the movie. Instead, it’s a fairly conventional overview of his life, music, and impact, including a good number of fine archive clips, including one from when he was still in Miles Davis’s group. A lot of people who were around Coltrane are not around at this point, but there are useful comments from a number of interviewees, including several of Coltrane’s sons and daughters, McCoy Tyner, Sonny Rollins, Benny Golson, and Wayne Shorter. Bill Clinton even testifies to Coltrane’s importance, with Denzel Washington adding some narration from Coltrane’s writings.

Of Coltrane’s albums, only A Love Supreme (and, in less depth, Giant Steps) get substantial coverage. For that reason, some Coltrane fans might feel a little unsatisfied, or certainly that an additional hour or so would have given a more complete record of his achievements. Given that this is probably targeted toward a more general audience, however, this does a decent job of representing his musical evolution and touching on his most significant achievements. A small note which is not a criticism: as long as Santana and Densmore were interviewed (and their comments are relevant and expressed well), it might have also been neat to have a bit from Roger McGuinn about Coltrane’s substantial influence on the Byrds’ most celebrated psychedelic song, “Eight Miles High.”

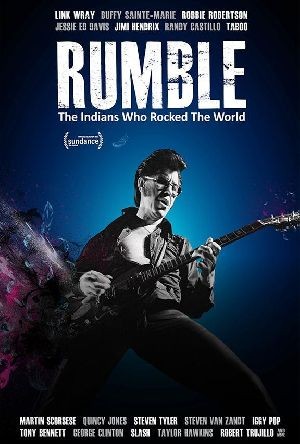

5. Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked the World. Native Americans have played notable roles in rock since its beginnings in the mid-to-late 1950s, when Link Wray was one of the most innovative early rock guitarists. This documentary covers some of the most notable Native Americans in rock (though some of them were only partially Native American), particularly Robbie Robertson of the Band, guitarist Jesse Ed Davis, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Redbone, and Jimi Hendrix (one of the figures whose ancestry was less than half Native American). Any film that gives some mainstream exposure to Wray and Sainte-Marie is worthwhile in my book, but that doesn’t mean this is an ideal survey. Some of the figures covered, like early bluesman Charley Patton and jazz singer Mildred Bailey, were active in non-rock styles that might have been influential on rock, but weren’t rock per se. There is more to say about some, maybe most, of the spotlighted musicians than this film fits in; the segment on Redbone doesn’t give much of a sense of their sound beyond their big hit “Come and Get Your Love.” It’s a matter of personal taste, but I wasn’t interested in the metal and hip-hop artists covered, even if it brought the story more up to date.

Some viewers might feel it’s inappropriate to judge a film on what it doesn’t do rather than what’s there, but I wish this project could have been a series with full episodes on outstanding musicians, rather than a single feature that mixed them together. Within the movie itself, the focus sometimes wavers and rambles, with an occasional sense that they’re building up some performers’ Native American connections to make sure the end result reaches feature length. Some critics and friends did like the film more than I did, and increasing awareness of Wray, Sainte-Marie, and Davis in particular makes this a worthy effort in some key respects.

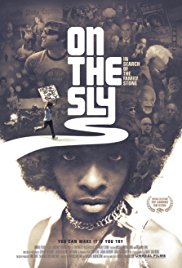

6. On the Sly: In Search of the Family Stone. Sly Stone superfan Michael Rubenstone spent years trying to interview the legendarily eccentric and reclusive Sly for a documentary he was trying to make on the soul star. It’s hardly a spoiler to reveal that he didn’t get the interview; Sly has barely appeared in public for many years. But along the way, Rubenstone did speak to a lot of people who knew and worked with Sly, including Freddie Stone, Cynthia Robinson, Jerry Martini, Gregg Errico, and ex-manager David Kapralik. While the absence of comments from Sly makes this an incomplete picture, it’s nonetheless an interesting film, also drawing upon (if in brief bits) quite a few mesmerizing vintage performance/interview clips from the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Rubenstone’s fandom is a bit creepily obsessive, but then if he wasn’t so besotted with the band, a project like this would probably have never gotten done. It almost didn’t get done anyway, as most of the footage is from more than ten years ago. Rubenstone gave up for almost a decade, getting especially discouraged after paying thousands of dollars for a Sly interview that never took place after the filmmaker was endlessly (if predictably) put off with shaky explanations. For that and quite a few other reasons, Sly does not come off as the most admirable of characters, inexplicably sabotaging his career when he seemed to have everything going for him. At least the strength of Stone’s music comes through, both from the vintage footage and the comments of his collaborators. This film is still flying way below the radar, having only played at a few festivals and special events (I saw it at the San Francisco Museum of the African Diaspora), though hopefully it will get wider distribution and eventual DVD release.

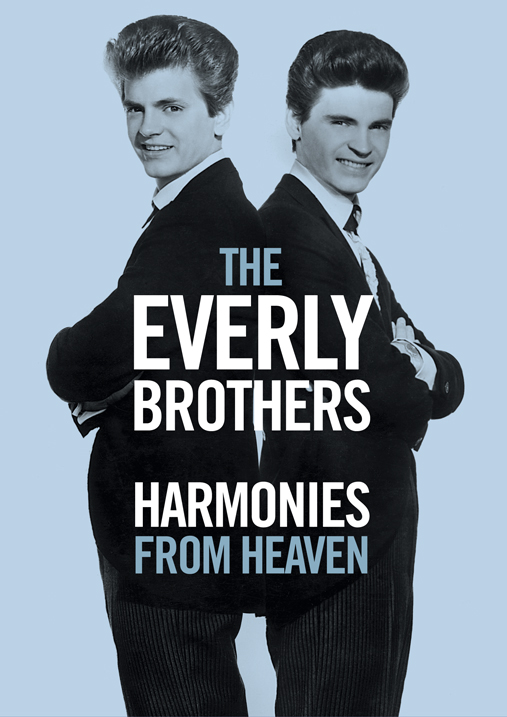

7. The Everly Brothers, Harmonies from Heaven (Eagle Vision DVD, 2016). This two-DVD release devotes one disc to an hour-long BBC documentary (with some additional interview material in the bonus features), and another to a live 1968 performance at a Sydney nightclub that was broadcast on Australian TV. You could easily make a good two-hour documentary on the Everlys instead of a sixty-minute one, and while there are some good interviews and vintage footage, there are also significant problems. There are too many talking heads, even if some of them are very relevant (both Everlys, a son of Boudleaux and Felice Bryant) or noted big fans who got to work with them (Art Garfunkel, Keith Richards, Graham Nash, Albert Lee). Some of them are not relevant, like Tim Rice and some producers, musicians, and critics who aren’t as famous or interesting. There are a wealth of excerpts from cool ‘50s and ‘60s clips which would be great to see in full, but are frustratingly short.

Also, the commentary is often overcontextualized, drifting into general observations about early rock’n’roll, radio, and Nashville that are both unnecessary and take away time from more specific discussion of the Everlys. Although most of their early hits are discussed, their post-early-’60s career—which included quite a few good records, even if most of them weren’t commercially successful—is almost dismissed, barely getting mentioned. Don Everly does look a bit frail in his interview segments (Phil is represented by 2010 interviews done before his death), but he’s wholly articulate, and there seems no reason why more in-depth commentary from him wasn’t used. (Here’s one zinger he offers on his relationship with Phil: “We never got along. He was different than I. He was a Republican, I was a Democrat. I couldn’t believe he was voting for Republicans, I just couldn’t believe it. I was a complete Democrat. I was just a leftist.”) Rock’n’Roll Odyssey, a 1984 PBS special on the Everlys, did a better job, and is more highly recommended than this documentary, although it has performance footage from numerous sources (again, it must be said, brief) not tapped for the PBS doc.

The second disc is quite good, and better than you might expect given it’s from a half-dozen or so years after the Everlys stopped landing American hits. Don does talk too much between songs, and some of the comic bits are kind of dumb. But the duo and their backing band rock pretty hard, on a set including many of their early hits, even if a few of them are truncated or kind of rushed. It’s a little odd and unfortunate that even at this stage they were mostly an oldies act, but they do put it in a couple of their better country-rock-flavored late-’60s songs, “Bowling Green” and “Kentucky.”

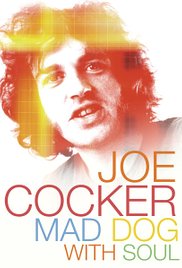

8. Joe Cocker: Mad Dog with Soul. Documentaries that are only or primarily available online have become a trend in music docs. This one from Netflix on Joe Cocker is another, though in common with other such items that have made my lists, the production’s as good as what you’ll see in standard theatrical releases. Unlike a good number of documentaries on music and other subjects these days, it doesn’t take an obtuse or arty approach, instead just digging into a straightforward chronological survey of the singer’s life and career. That’s generally good news, and it does work here, alternating judiciously placed Cocker archive concert and interview footage with interviews with those who worked closely with him and knew him well. Among those interviewed with valuable observations are longtime Cocker keyboardist Chris Stainton, A&M Records executive Jerry Moss, producer Glyn Johns, Rita Coolidge (a backup singer on his Mad Dogs and Englishmen tour), Jimmy Webb, brother Vic Cocker, wife Pam Cocker, and manager Michael Lang.

However, through no fault of the filmmakers, the last half of the movie isn’t nearly as interesting as the earlier part. True, there are very few music documentaries where the second half is more interesting than the first half, given how many artists peak early in their career, if their career lasts more than ten years. But a lot of momentum’s lost after the Mad Dogs and Englishmen tour, and even more after the 1970s, with all of Cocker’s finest work coming in the first few years of his recordings. It is sad, if instructive, to hear the many tales of his alcoholic excess, though just a bit cheering that he straightened out, relatively speaking, in his latter years. If there’s a villain in this piece, it’s manager Dee Anthony, whose insistence (according to some interviewed here) that Cocker do the lengthy, unprofitable, and exhausting Mad Dogs and Englishmen tour when he could have used a rest contributed to his early burnout.

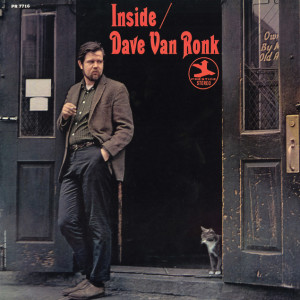

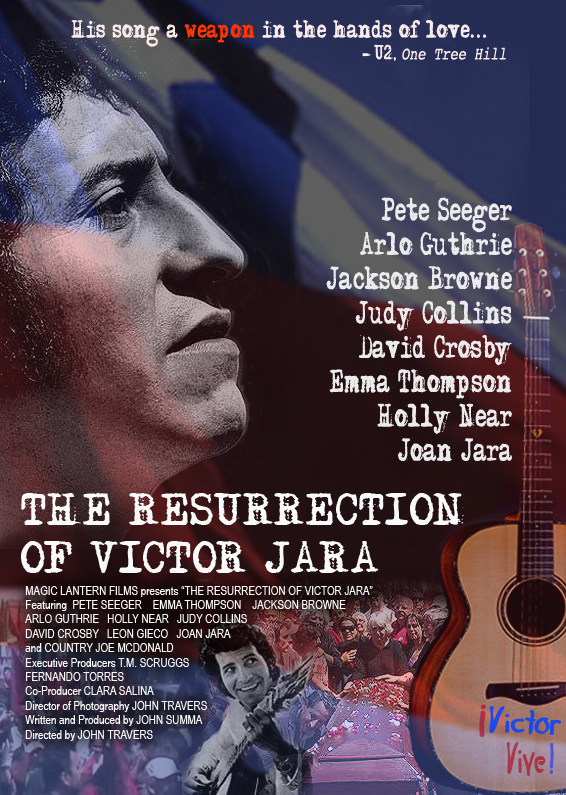

9. The Resurrection of Victor Jara. This film was actually first screened in 2015, but to my knowledge it didn’t make it to San Francisco until I saw it in February 2017, and then screened just once in a small space during a festival. A legend in Chile, folksinger Jara is most known in North America for having been executed in 1973 after a military coup in that country. In part sparked by this, Phil Ochs organized a benefit for the Friends of Chile in May 1974, at which he, Bob Dylan, Arlo Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Melanie, Dave Van Ronk, and others performed. These events are covered in this documentary, but its focus is on Jara’s life as a whole, including his music and its influence from the mid-’60s to the early ‘70s, and how his memory was honored in Chile over the last few decades.

Actually, its focus was too diffuse for me; I felt I didn’t get a full grasp on his pre-musical career, how he came to be one of Chile’s most popular musicians, and the political activism of his life and songs. There are a good number of vintage clips, if usually brief and fuzzy, and some of his musical peers are interviewed, as well as American admirers like Guthrie and Judy Collins. It’s of value to most music fans interested in the relation between music and social activism, and a reminder that as bad as things are in many parts of the world now (including the US), they were really bad in the US-supported 1973 Chilean coup, where artists such as Jara were tortured and killed.

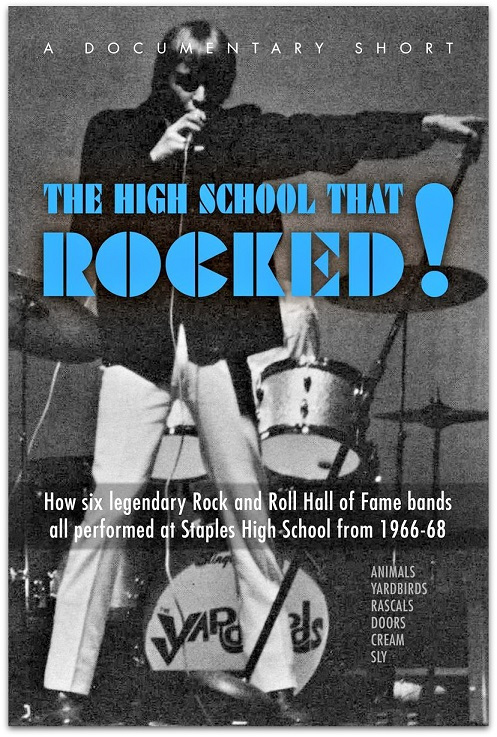

10. The High School That Rocked! You might think it a stretch to make a film, even a short, about the rock concerts at a suburban high school. Staples High School in Westport, Connecticut, however, wasn’t a typical such place, at least in terms of the acts it managed to book in the mid-1960s. Unbelievably, the Beau Brummels, Animals, Remains, Yardbirds (the Jeff Beck-Jimmy Page lineup), the Rascals, the Doors, Cream, Phil Ochs, Sly & the Family Stone, and Buddy Miles all played there within about four years in 1965-69. Although it’s not in wide circulation, this 27-minute documentary is well-paced and well made, emphasizing comments by students that don’t get overlong, trivial, or overstay their welcome. Their memories of the concerts and fleeting interactions with the stars (the class president even inviting the Yardbirds back to his home after the concert) are enhanced by plenty of vintage photos of the concerts, newspaper clippings, and local radio charts.

How exactly did a high school, even from a fairly well off area, get so many plum acts? It was in large part due to students Dick Sandhaus and Paul Gambaccini (later a noted rock critic), who managed to make connections, particularly through rising talent agent Frank Barsalona, that secured some stars. One student, Charlie Karp, even ended up joining Buddy Miles’s band after his group backed Miles when the drummer played the school. He’s one of the students interviewed for this short, which has played some festivals, and is certainly worthy of screenings on public television.

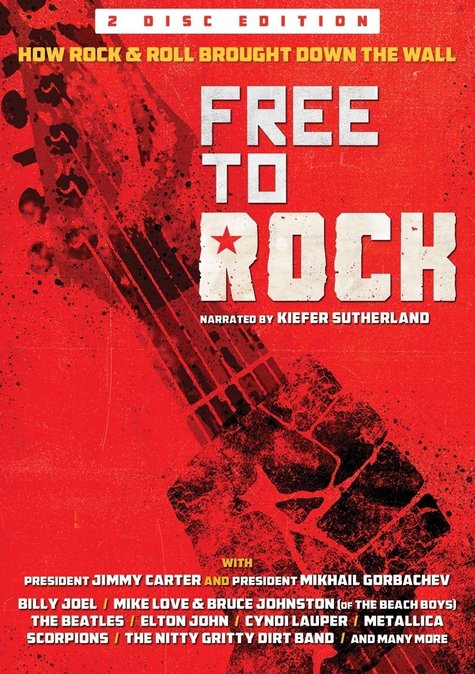

11. Free to Rock (PSB Records, DVD). There will probably never be another documentary that gives roughly equal attention to Billy Joel and the Plastic People of the Universe. This 55-minute one does, however, by virtue of its unusual subject, examining how rock and roll helped bring down the regimes behind the Iron Curtain, especially in the Soviet Union, East Germany, and Czechoslovakia. There are interesting interviews (usually conducted in English without translation) with Soviet rockers of the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s, as well as some vintage film clips (though these are pretty brief) of those musicians in action. Rock musicians in other Eastern Bloc countries are also interviewed, discussed, and seen, including Czechoslovakia’s Plastic People of the Universe, whose way-underground Zappa/Velvet Underground-influenced sounds were crucial to the dissident movement that eventually overthrew the country’s rulers.

Also covered are the Western stars who played behind the Iron Curtain before the Berlin Wall and the Soviet regime fell, including the Beach Boys, the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, Elton John, Billy Joel, and heavy metal acts like the Scorpions. Also interviewed are heavyweight politicians like Jimmy Carter, Mikhail Gorbachev, and even former KGB general Oleg Kalugin, though the musicians struggling to function and express themselves under these regimes are the most thought-provoking.

There’s the sense that much more could be said about the complex factors both driving the music being made in these regions and the social changes they ignited. (Some of these are explicated in the two-hour bonus disc, mostly of extended interviews, though in common with many such extras, they tend to be drawn out and drag after a while.) It can also be said that some of the music by the Soviet and Eastern bloc bands, as admirable as it was to have performed it under such repressive conditions, isn’t very good—and that some of the Western stars who managed to play in those countries before the early 1990s weren’t exactly the greatest the rest of the world had to offer. But even if it’s a bit of rush to document such massive movements in less than an hour, it’s still a worthy overview.

12. Ticket to Write. A documentary on rock criticism from the mid-1960s to the early 1980s (with a technical release date of 2016, though I saw it at a film festival in early 2017), this as expected focuses on interviews with rock journalists of the era. These include such well known ones as Ben Fong-Torres, Ed Ward, John Morthland, Sandy Pearlman, Gene Sculatti, Ira Robbins, and Jaan Uhelszki (with some too young to have been writing then, like Mike Stax of Ugly Things, providing some historical context). Its strengths are that some good stories are told, like the one about hookers descending upon a rock critics convention in the early 1970s, only to realize that guys getting paid $25 per review (if they were lucky) were not exactly prime targets. As a film, it has problems. The narration is overbearing; the sound quality of the interviews erratic; and the background music sometimes doesn’t sit comfortably in the mix of a talking head-heavy documentary. I also found some of the premises baffling, such as championing the Dictators as a turning point of sorts in reviving rock from the doldrums in the mid-1970s. And MTV is too conveniently pinpointed as a villain that killed the golden age of rock criticism, though there’s been plenty of rock writing since the early 1980s, even if there may never again be publications with the reach and influence of Rolling Stone, Creem, and Trouser Press. Barely any UK writers are involved, which means this is really an overview, if a flawed one, of US rock criticism of the era.