“The Beatles Vs. The Rolling Stones” – it’s kind of a silly debate, if not nearly as silly as “The Beatles Vs. The Four Seasons,” as Vee-Jay Records titled one cash-in LP. You’ve got what many, even tens of millions, consider two of the greatest rock bands of all time – do you really have to choose one over the other? Or, worse, choose one and not the other, as some hard-liners (more Stones fanatics than Beatlemaniacs) maintain? They’re both great (or, at least, the Stones were great), and I’ve taught comprehensive courses on both groups.

But here’s something I’ve never seen brought up when “The Beatles Vs. The Rolling Stones” is mentioned – how did those bands fare on the relatively rare occasions when they did go head-to-head? Not on the same stage or boxing ring or anything like that, but on the same song? For the two acts did sometimes do the same song, and a little more often than many think. True, there were just two occasions when they actually released studio versions of the same number. But if you count BBC and live performances, the quantity nearly doubles, though even then, it doesn’t reach double figures. Taking the attitude that no one else will do this unless I will, here’s a play-by-play rundown of those infrequent instances when the titans performed the same tune, with just-for-fun verdicts that shouldn’t be taken too seriously.

Let’s start with the only two songs the Beatles and Stones both did in the studio, with all four versions, as it happens, getting waxed in 1963 near the beginning of their careers.

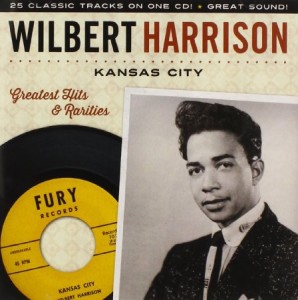

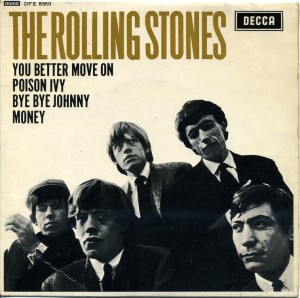

Money: Despite the differences between the groups played up by the media and some fans, the two bands actually admired quite a few of the same US rock and soul artists, and it’s not all that surprising that they would cover some of the same songs. The only such animal to make it onto their 1963 discs, however, was “Money,” one of the first Motown hits (though not quite as big as many remember, Barrett Strong’s original peaking at #23 in 1960).

The Beatles did “Money” on their second album, and it’s really not all that controversial an opinion to assert they totally outdistanced the original, both by virtue of John Lennon’s fierce lead vocal and Paul McCartney and George Harrison’s exuberant backup harmonies. There are actually a few Beatles versions of “Money,” starting with a fairly anemic one from their January 1, 1962 audition for Decca Records (with Pete Best still on drums), and also including a half-dozen BBC performances. The studio cut on With the Beatles, however, is the best from every angle, and one of the best of the many fine covers they recorded.

It’s also not that controversial an opinion to declare that the Beatles pretty much kill the Stones in an A-B comparison of their respective versions. In fact, a lot of listeners probably still don’t even know the Stones did “Money,” as it first appeared on a January 1964 UK EP, and wasn’t issued in the States until the More Hot Rocks compilation almost ten years later. The Rolling Stones’ version is raw to the point of almost being sloppy, has rather hoarse and untutored backup vocals, and is pretty murkily recorded (though it’s hardly alone in that last department among early Stones tracks). For all that, it’s not that bad, with some cool if slightly haphazard harmonica and generally commendable enthusiasm. The Stones were hardly the only other British Invasion group to do “Money,” by the way, other entries being cut by Freddie & the Dreamers (a predictably silly and stilted one) and Bern Elliott & the Fenmen (who took their rather generic interpretation to #14 in the UK), among others.

The Verdict: Still – a clear victory, perhaps even a knockout, for the Beatles.

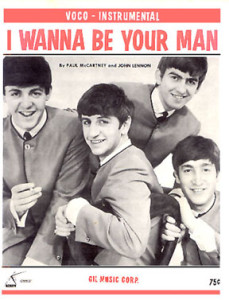

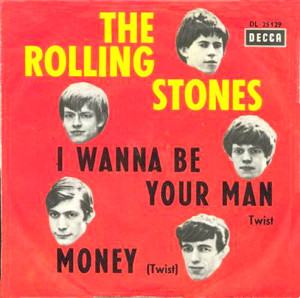

I Wanna Be Your Man: The other song the Beatles and Stones cut studio versions of in 1963 wasn’t even, for one of the bands at least, a cover. The famous story’s a little too long to recap here, but basically Stones manager Andrew Oldham, in need of a song for his clients’ second single, stumbled into John Lennon and Paul McCartney in central London, and corralled them into visiting a Stones rehearsal, where they finished off “I Wanna Be Your Man” on the spot. “I Wanna Be Your Man” would be the Rolling Stones’ first substantial British hit (stopping just short of the Top Ten), though it wouldn’t even be an A-side in the US, where it didn’t even appear on an LP (or, for many years, even on a compilation).

Though it was released a few weeks after the Stones’ version, the Beatles’ rendition was recorded about a month earlier. While something of a filler track on Meet the Beatles, with lyrics even more basic than most of the early Lennon-McCartney compositions, it pummels along with great, slightly bluesy effervescence, Ringo Starr on lead. It’s a good rocker, if a fairly secondary one in the scheme of early Beatles material. A little later, they’d do a cool version on the BBC with a slight Bo Diddley beat.

That said, the Rolling Stones’ arrangement beats the Beatles hands down. The slide guitar by Brian Jones is downright vicious, Bill Wyman plays an into-the-red pumping bass, and Mick Jagger gives it a sneer wholly missing in Ringo’s vocal. Where the Beatles play it jocular, the Rolling Stones are assaultive, bringing out the song’s subtle blues flavor so that it becomes a genuine pounding blues-rocker. John and Paul gave them a great assist by giving them the tune, but the Stones made it in their own, in a version both superior to and quite different than the Beatles’.

The Verdict: A clear victory for the Stones, though not the knockout that “Money” was for the Beatles.

Now we’ll start getting into territory beyond the two official instances in which the bands released the same song, much of which remains unknown to the general public:

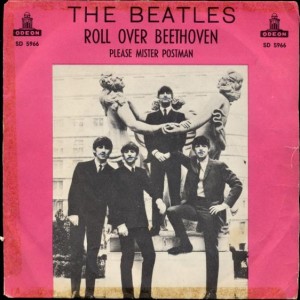

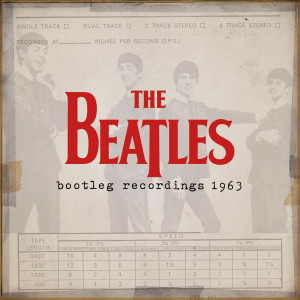

Roll Over Beethoven: Another highlight from the Beatles’ second album, “Roll Over Beethoven” was an excellent Chuck Berry cover, from George Harrison’s adept soloing (and lead vocal) to the insistent propulsion of the rest of the band on backup. Again they did this a bunch of times on the BBC (a particularly good June 24, 1963 one with a twice-as-long instrumental solo is on the iTunes download-only compilation The Beatles Bootleg Recordings 1963), and there are good live versions floating around on tape and film (though the one done in Hamburg in December 1962, like the rest of the live tapes from that quasi-official batch, has pretty poor sound).

It’s still not generally known that the Rolling Stones recorded “Roll Over Beethoven” at a BBC session on September 23, 1963, in large part because it still hasn’t been officially released. Bootlegged with very good sound, it’s a tremendous version, and, again, quite different to the one by the Beatles. Keith Richards’s guitar has a more raucous edge, Mick Jagger’s vocal a more cutting bluesy tone, and the tempo’s more frenetic. Most notably, Richards unleashes a simply marvelous solo with a heck of a lot more bluesy note-bending. Of the numerous songs the Stones did on the BBC without counterparts on their official records (though these weren’t nearly as numerous as the ones the Beatles taped), “Roll Over Beethoven” might be the very best. (They also did a less impressive, looser version of “Roll Over Beethoven” at a later BBC session on March 8 , 1964.)

The Rolling Stones performed “Roll Over Beethoven” on BBC radio in 1963, but did not release a studio version.

The Verdict: Too close to call, really, though if pressed I might choose the Stones’ version, Keith’s solo being the deciding factor.

Carol: Another Chuck Berry song both bands did, the twist being that this time, the Rolling Stones’ version is the more familiar one. “Carol” was a highlight of the band’s first album in 1964, with a pushy buzz, and authoritative Keith Richards guitar licks, that made it slightly different from the original, if not terribly different.

The Beatles did not record this at EMI, but did a top-flight version for the BBC on July 2, 1963. Much more well known to the general listener after its official appearance on Live at the BBC in 1994, it was one of five songs from this session they didn’t put on their 1960s releases. Let me quote from my description in my book The Unreleased Beatles: Music and Film: “’Carol’ is handled here by John on solo vocals, and slightly precedes the much more famous delivery of the same song by the Rolling Stones on their debut 1964 album. It’s a contentious assertion, but the Beatles’ less noted interpretation is yet better than the one by the Stones, who took the song at a much more even, clipped beat. The Beatles’ interpretation has a more forward-thrusting groove, Lennon’s best cocky rock ’n’ roll voice, and propulsive Harrison guitar riffing, especially when he flicks off some cliff-descending notes near the end of the instrumental break.”

The Verdict: Like the above paragraph notes, a contentious assertion, but I think this is a clear victory for the Beatles, though the Rolling Stones’ effort is quite respectable. Incidentally, the Stones also put a different live version from late 1969 1969 on their hit concert album Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!, recorded with Mick Taylor, who replaced Brian Jones in mid-1969, on one of the guitars.

Memphis, Tennessee: Here we have a case of a song that neither the Beatles nor the Rolling Stones put on their official ‘60s releases, though both did it for the BBC. The Beatles, in fact, had done it on January 1, 1962 back at their Decca audition, and at their first BBC session on March 7, 1962, with Pete Best still on drums. Their arrangement (and indeed the whole band) had improved by the time they did it four more times for the BBC (with Ringo) in 1963, John Lennon still on lead vocals. On the whole, though, it’s not one of their better covers, though it’s okay.

Again, not many people are aware the Rolling Stones did “Memphis” too, as their September 23, 1963 BBC version (recorded at the same session they did “Roll Over Beethoven”) hasn’t been officially released. Which is too bad, in part because it’s decisively better than the Beatles’. The Beatles’ arrangement is a little lumpy, but the Stones do it with just the right deftness, exquisitely interwoven guitars, and an appropriately wistful Mick Jagger vocal. As an aside, it is a shame that just four of the band’s 1963-65 BBC tracks have come out (and then only as a bonus disc on the expensive super-deluxe edition of their GRRR! compilation), as there are enough to fill up a double CD.

The Verdict: A clear victory for the Rolling Stones, which doesn’t mean that the Beatles’ 1963 BBC versions (some of which have been officially issued) aren’t worth having.

I’m Talking About You: As if there’s any doubt that Chuck Berry was the most common meeting point in their influences, here’s yet another song covered by both bands. The Rolling Stones’ version (slightly retitled “Talkin’ Bout You”) is by far the more familiar, having appeared back in 1965 on the December’s Children LP (in the US) and the Out of Our Heads LP (in the UK). It’s a good one that’s funkier and slyer in execution that the original. The group, incidentally, did a yet earlier version for the BBC on September 23, 1963 (in the same batch including “Roll Over Beethoven” and “Memphis, Tennessee”) that unfortunately hasn’t survived. For that matter, that same session included a version of “Money” that didn’t survive either.

Until very recently, the best of the two surviving Beatles versions of “I’m Talking About You” was quite obscure. An energetic but lo-fi one from December 1962 had been available since 1977 on the Hamburg Star-Club tapes. A better, though not totally hi-fi, BBC performance from March 16, 1963 finally came out in late 2013 on On Air: Live at the BBC Vol. 2. It’s pretty good as well, benefiting from a brash John Lennon lead vocal, and an odd chuckle right before they go into the instrumental break, with a George Harrison solo that (like many of his BBC performances) are rawer than what he was wont to put on the group’s studio releases. The bass line of the Chuck Berry original, incidentally, provided the inspiration for Paul McCartney’s bass on “I Saw Her Standing There.”

The Beatles’ BBC version of “I’m Talking About You” is included on this 2013 compilation.

Still – the Beatles’ version is not quite as distinctive, or as different from the original, as the Stones’ take. So –

The Verdict: A decisive win for the Rolling Stones, though not by a huge margin.

Little Queenie: It’s rather amazing – of the half-dozen recordings of seriously performed songs that both the Beatles and the Rolling Stones did in the 1960s, four were Chuck Berry tunes. Again, this should eliminate any doubt that he was their most common shared point of reference, though no doubt there were some other songs (by Berry and others) both bands covered that one or both of them didn’t put on surviving tapes.

The Stones’ version of “Little Queenie” is by far the better known of the two, a late-’69 concert performance having featured on their Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out! album. Give the group credit for not just replicating Berry’s version (which some of their earlier Berry covers verge on doing) but slowing it down considerably and making it funkier and more salacious, though that was in keeping with how their whole approach had changed by the late 1960s, especially with Brian Jones out of the band.

It’s a shame that the only existing Beatles performance of “Little Queenie” is from their lo-fi December 1962 Star-Club tapes, which makes it a little hard to properly face off against the much later one by the Stones. Nonetheless, I’ll go out on a limb and say the Beatles’ version is better. It has a terrifically infectious Paul McCartney vocal, and a really unusual, exhilarating George Harrison guitar solo that has no counterpart in the Berry original. If only they’d recorded this for the BBC in good fidelity, a la “Carol,” there would be no doubt whether this surpassed the Stones’ interpretation. Nonetheless –

The Verdict: The Beatles win, though the marginal fidelity of their version, and the respectable quality of the Stones’ rendition, makes it something of a borderline triumph.

The only Beatles version of “Little Queenie” is on the tapes they recorded in Hamburg in December 1962.

By the way, the Beatles did casually jam on a few other songs the Stones also did during their January 1969 sessions for what was then intended to be the Get Back album and film, though it would be retitled Let It Be. Among them were Chuck Berry’s “Around and Around,” Marvin Gaye’s “Hitch Hike,” Hank Snow/Ray Charles’s “I’m Movin’ On,” Buddy Holly’s “Not Fade Away,” and even the Stones’ own “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” and “Lady Jane.” These were just too casually executed, however (and sometimes poorly recorded), to consider serious attempts at a recordable performance. For that reason, they’ve been excluded from this discussion, though for what it’s worth, the versions of “Hitch Hike” (with George Harrison’s fine lead vocals sadly undermiked) and “Not Fade Away” (ditto) aren’t bad.

In sum – is there a winner in the Beatles vs. the Rolling Stones? Even if judged solely on the few songs on which they went toe-to-toe? Seems to me it’s about as close to a draw as it gets. And isn’t that how it should be?