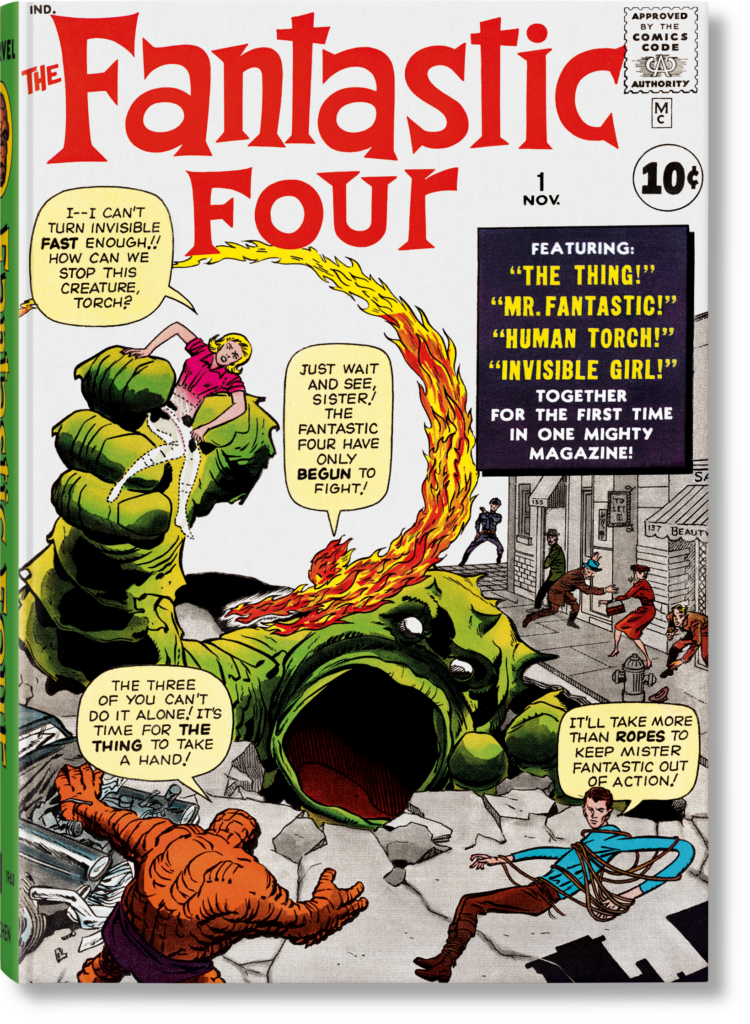

I’m not a comic book collector or expert, but I am fairly interested in the subject, and in the early days of Marvel comics. So I got recent high-end coffee table volumes that reproduced the first twenty issues of Spiderman and, more recently, the first twenty issues of Fantastic Four. I’m less familiar with Fantastic Four than Spiderman, my knowledge of the content coming from, in both cases, copies of the original issues older brothers bought in the early to mid-1960s.

I knew the basics of the Fantastic Four characters and their origins, but had not previously read these 1961-63 issues in their entirety. Here are a few things that struck me about them, which have quite possibly been analyzed in much greater depth in publications spanning fanzines to academic tomes.

1. There’s much more of a Cold War presence and anti-Communist sentiment than I was aware of.

It’s sometimes thought that anti-Communist hysteria in the US toned down a lot after it peaked during the worst of the McCarthy era in the early 1950s. That could be true in some respects, but the House Un-American Activities Committee was still active as the 1960s started. Protests against hearings it held in San Francisco in 1960 have been cited as one of the key sparks of anti-authoritarian demonstrations and dissent in the 1960s in general.

Certainly there are more than traces of this in the early Fantastic Four issues, going back to the pages that — in two separate issues, told somewhat differently each time — explain their origins. It’s not obscure that the quartet got their powers when they were exposed to cosmic rays during a failed rocket mission to outer space. Not as universally known, perhaps, is that a big part of the reason they were in such a rush to get on the rocket, despite the uncertainty about exposure to comic rays, was to beat the Communists in the space race. As Sue Storm told Ben Grimm (aka The Thing) to convince him to pilot the rocket in the first of these origin stories, “We’ve got to take that chance…unless we want the commies to beat us to it!”

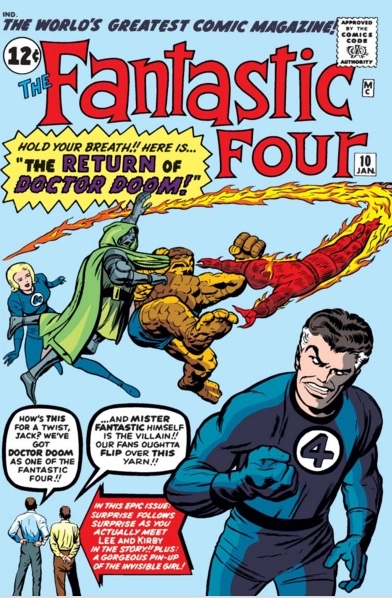

This was phrased in a different way when the origin story’s re-presented in issue #10. Here Reed Richards states, “The world we had fought for was also not yet ours!” — referring to his service in World War II, and the ensuing Cold War for world domination. Adds Reed, “We’ve got to reach the stars before the reds do! That’s why I’ve spent a fortune working on my own design for a space ship!” to which Sue rejoins, “Oh, Reed, if only the government had listened to you in time—heeded your warning!” There’s another Cold War reference when Reed pleads to Ben, “You’ve got to do it, Ben! You’ve got to fly her for me! You’re the only pilot in the free world who can do it!”

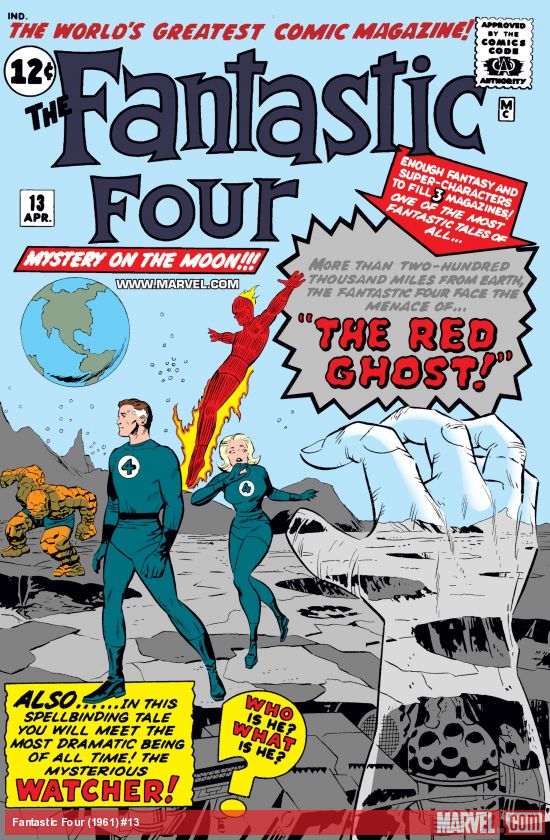

Unkindly, it could be argued that this mission was a terrible failure in its objective, crash landing on earth when a cosmic storm derailed the journey. Or, that it was a quirky success in the cosmic rays granting the Fantastic Four powers to use for the good of mankind — which would include, from Marvel’s perspective, occasionally waging part of the Cold War. In issue #12, prominently featuring the then-new Hulk character, the undercover villain has, in the words of another character, “a membership card in a subversive communist-front organization! That means — [he] must be — a red!” A different villain in #13 connects the Cold War and the space race with the boast, “At last my crew of apes is ready! And now—we go to the moon—to claim it for the communist empire!”

In that issue, “The Watcher” takes a role that, whether deliberately or unconsciously, intimates the futility and madness underlying the struggles between the “reds” and the free world. “I have broken the silence of centuries, in order to save your people from savagery!” he intoned. Retorts the villain, “You dare think you can stop the communist march of conquest!?”

In a speech that might have been influenced by the alien visitor in the 1951 film The Day the Earth Stood Still, the Watcher announces, “Sooner or later, both your nations may engage in a war which might devastate your entire planet! That is not my concern! But now you bring your conflict to the moon–to my domain! I will tolerate no large scale war here!” This doesn’t motivate the Fantastic Four, alas, to consider the value of fighting their enemies, and they simply focus on battling “the commies,” as The Thing refers to them a couple times in the next couple pages. Reed Richards tows the party line by reminding The Thing, “Ben, nobody is strong enough to defeat a free people! Don’t ever forget that!”

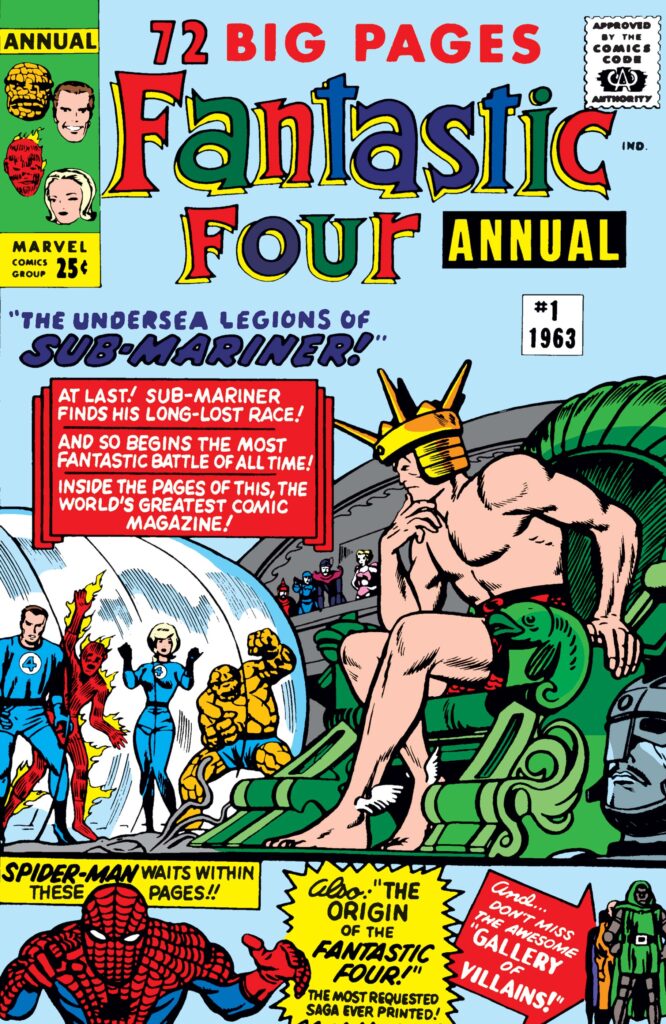

Even as Fantastic Four got well into 1963 and the Kennedy administration, anti-communist sentiment lingered. News of Dr. Doom’s latest threats travels quickly — to behind the Iron Curtain, where a caricatured Soviet official proclaims, “Soon the capitalistic countries will be helpless before us!” And in 1963’s Fantastic Four Annual, Namor’s latest threat is dismissed by a Soviet in the UN thusly: “Bah! It is all a pack of capitalistic lies! No matter what the democracies say, I vote nyet! Nyet! Nyet!” The bureaucrat isn’t named, but the shoe he beats on his desk makes it obvious he’s supposed to represent Nikita Khrushchev.

I suppose it could be construed that the numerous horrible villains threatening not just the free world, but the world and humanity themselves, in Fantastic Four and other comics and horror films could represent the subconscious fears of the monsters that would emerge if communism were allowed to prevail. It could certainly be argued, however, that the Cold War seemed kind of trivial compared to the graver threats the likes of Dr. Doom, the Puppet Master, the Mole Man, and others were posing to not just the Fantastic Four, but the entire human race.

2. Namor The Sub-Mariner and (or vs.) Spock

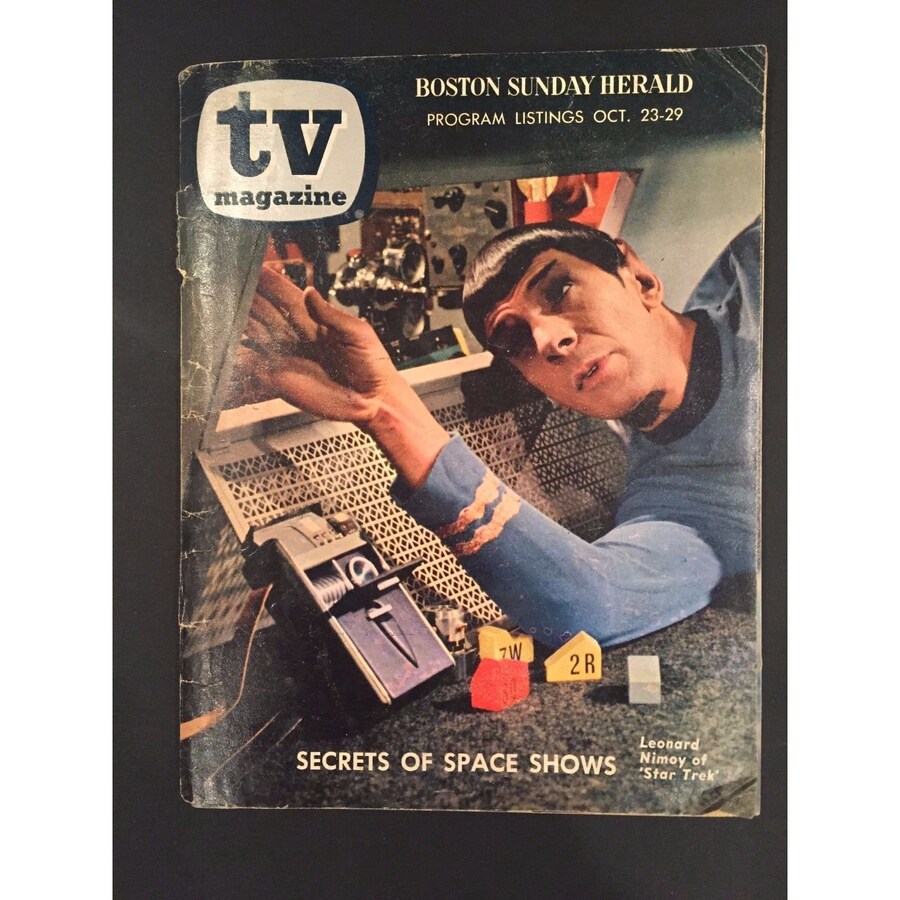

Parallels between Namor the Sub-Mariner, the maybe-not-always-villain in Fantastic Four, and Star Trek‘s Mr. Spock have hardly gone unnoticed. Go online and several articles quickly appear about the possible connections. I noticed them more going through this book, though, than I did in the past.

First, there’s the physical resemblance. It might be uncanny, but I don’t think Star Trek was deliberately trying to emulate Namor’s appearance with the Spock character. It seems more like an interesting coincidence that Leonard Nimoy’s physique lent himself so much to an image with a fair amount of similarity.

Of more importance — and a key point that didn’t emerge until the 1963 annual — is both Spock and Namor’s mixed-species background. You probably weren’t even on earth if you don’t know that Spock is half-human, half-Vulcan. Not everyone, however, knows that the Sub-Mariner is half-human, and half part of the Atlantean race he’s supposed to be reviving/leading.

As with Spock, this is the cause of considerable unease, even as it grants him some powers and depth not reachable by either of his ancestral races. As with Spock, he doesn’t feel wholly at home either with humans or with the race with which he primarily identifies—the Vulcans, for Spock, and Atlanteans, for Namor. “Am I to be a king without a kingdom—a man without a home?” he lamented at the end of the Annual. “More than a sea creature—yet, less than human! Is there never a place for me—on the surface, or in the sea?”

Although he’s nominally a villain, Namor also seems to have more humanity, integrity, and at times compassion than any of the other regular evildoers in Fantastic Four. This seems to be intuitively sensed by Sue Storm, who grasps Namor is often misunderstood and motivated by reasons unrelated to a thirst for world domination. “He isn’t bad,” she contends at one point. “He’s fighting for what he believes in, the same as we humans are!,” perhaps getting to the root of his mixed-ancestry dilemma more than she realizes. This compassion, at times passion, for Namor is the cause of much consternation among the Fantastic Four, particularly the more straightlaced yet honestly more boring Reed Richards, who hopes to marry Sue. It’s not commented upon that Sue’s intuitive sense of Namor’s better qualities isn’t that far removed from how Alicia, blind stepdaughter of the Puppet Master, intuits the inherent goodness under her boyfriend The Thing’s gruff exterior.

Yet these comparisons only stretch so far. Spock might be half-human and half-Vulcan, but he’s not half-good and half-evil, or even mostly evil and a bit good. The essential decency of Spock is rarely in question, even if he’s sometimes cold about expressing friendship and gratitude. Although he often claims not to have emotions, neither is the strength of the friendship he feels with at least some humans — with Captain Kirk of course, but even with Dr. McCoy, despite their frequent squabbles. A woman on the Enterprise senses Spock’s more vulnerable side and loves him, but unlike Namor with Sue Storm, Spock doesn’t return the passion, or even seem to be submerging any romantic interest in Nurse Chapel.

Given the increasing intersection of major comic book and science fiction heroes, it seems inevitable that one day Spock and the Sub-Mariner will meet and exchange notes, perhaps in one of the time travels that often occurs in such characters’ adventures. For all I know, that’s already happened.

One plot point not remarked upon in this series of initial issues: the Sub-Mariner would never have been unleashed to wreak havoc and revenge on the human race had not the Human Torch aka Johnny Storm found him in a flophouse and woken him from a sort of waking slumber. This is made clear in the issue containing this episode, but no one seems to acknowledge that the Sub-Mariner wouldn’t have been a force to deal with had the Human Torch not gone poking around where he wasn’t especially welcome or wanted. Kind of like how it wasn’t often acknowledged in the original Star Trek series that some of the threats the Enterprise faced might not have emerged had the starship not gone into space to go poking around in the first place.

3. The lurking counterculture.

One of the regular letter-writers featured in the Fantastic Four reader letters column was Paul Gambaccini. As regular as about anyone, at any rate, with three in the first twenty issues. At first Gambaccini was extremely critical — “artwork is horrible. Your heroes are lilly-lilly with obvious faking of emotions” reads part of the first one that was printed. A few issues later he was changing his tune, beginning a letter “Fantastic Four has greatly improved,” before venting a pretty lengthy series of suggestions and complaints. A huge and pretty complimentary letter in issue #17 concludes, “So you finally converted me!”

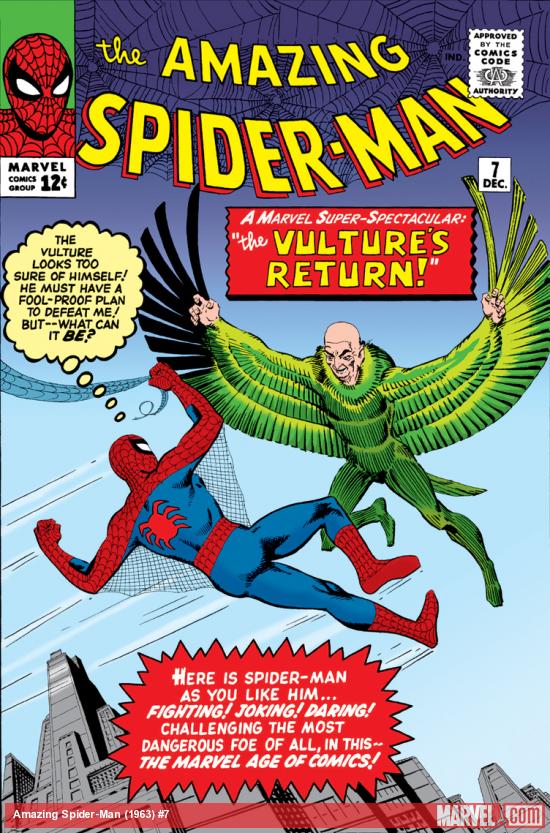

Gambaccini also wrote to Spiderman, starting his issue #7 letter “May I congratulate you (or should it be thank you) for the tremendous quality of Amazing Spiderman,” though he adds that originally “he was a run-of-the-mill deadbeat, typical of the baleful boredom which sometimes prevailed in your comics.”

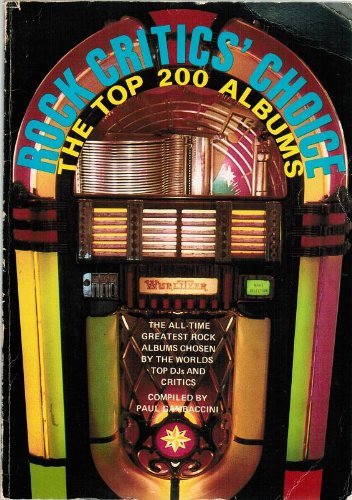

Gambaccini, a young teenager at the time of these letters, became a fairly prominent rock music critic. Moving to Britain, he’s long been a radio and TV host. In the US, he might be most known as the editor of Rock Critics’ Choice: The Top 200 Albums, the first widely distributed book devoted to an all-time poll of rock critics.

This leads back to some earlier points. I’ve read that Marvel found a particularly strong following in the incipient 1960s counterculture, among young people looking for something different, more complex, and more human in their superheroes. Marvel didn’t accomplish this so much through their scenarios, which often put the protagonists in situations where they had to triumph through might and smarts, but through their multi-faceted and often troubled human characters, who had emotions and problems not so different from real people, and from real adolescents.

It likely wasn’t noticed much or at all, but it could have been a misstep for Marvel, at least in early issues, to have an anti-communist Cold War mindset, verging on voicing government propaganda. Many of Marvel’s readers would soon, or might have already been questioning such entrenched and stereotypical attitudes. It could have been the residue of older writers and illustrators who’d been through actual, not cold, wars and were more inclined to follow the Establishment, at least in terms of government policy. Quite a few Marvel readers, I’d guess, would evolve to or at least include rock music as part of their emerging sense of a different generational identity.